Abstract

At least half of primary autonomic failure patients exhibit supine hypertension, despite profound impairments in sympathetic activity. While the mechanisms underlying this hypertension are unknown, plasma renin activity is often undetectable suggesting renin-angiotensin pathways are not involved. However, because aldosterone levels are preserved, we tested the hypothesis that angiotensin II is intact and contributes to the hypertension of autonomic failure. Indeed, circulating angiotensin II was paradoxically increased in hypertensive autonomic failure patients (52±5 pg/ml, n=11) compared to matched healthy controls (27±4 pg/ml, n=10; p=0.002), despite similarly low renin activity (0.19±0.06 versus 0.34±0.13 ng/ml/hr, respectively; p=0.449). To determine the contribution of angiotensin II to supine hypertension in these patients, we administered the AT1 receptor blocker losartan (50 mg) at bedtime in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (n=11). Losartan maximally reduced systolic blood pressure by 32±11 mmHg at 6 hours after administration (p<0.05), decreased nocturnal urinary sodium excretion (p=0.0461), and did not worsen morning orthostatic tolerance. In contrast, there was no effect of the captopril on supine blood pressure in a subset of these patients. These findings suggest that angiotensin II formation in autonomic failure is independent of plasma renin activity, and perhaps angiotensin converting enzyme. Furthermore, these studies suggest that elevations in angiotensin II contribute to the hypertension of autonomic failure, and provide rationale for the use of AT1 receptor blockers for treatment of these patients.

Keywords: autonomic nervous system, hypertension, angiotensin, drugs, natriuresis

Introduction

Primary autonomic failure is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by disabling orthostatic hypotension, in the setting of profound loss of sympathetic activity and absence of baroreceptor reflexes.(1) At least half of these patients are also hypertensive while lying down, which can be severe with systolic blood pressure (SBP) reaching >200 mmHg in some cases.(2) The supine hypertension increases nocturnal pressure natriuresis to promote volume depletion and worsening of morning orthostatic tolerance. It also complicates management of these patients by limiting use of daytime pressor agents for treatment of orthostatic hypotension. Finally, supine hypertension increases risk for cardiovascular events and for development of target organ damage including renal impairment and left ventricular hypertrophy in autonomic failure.(3;4) These findings provide rationale for pharmacologic treatment; however, the precise pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying the hypertension and the ideal antihypertensive therapies for these patients remain unclear.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is an important contributor to the development of hypertension, through actions of angiotensin II at AT1 receptors to stimulate vasoconstriction, baroreflex dysfunction and aldosterone release.(5) Blockade of angiotensin II formation with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or its actions with AT1 receptor blockers (ARBs), is well established for treatment of essential hypertension.(6) Previous studies, however, show that autonomic failure patients have very low and often undetectable plasma renin activity, blunted renin responses to postural and pharmacologic stimuli, and loss of renin immunoreactive cells in autopsied kidneys.(7;8) These collective findings suggest that renin mechanisms are not involved in the hypertension of autonomic failure. However, aldosterone levels are normal in these patients,(7) perhaps suggesting preservation of downstream RAS pathways for cardiovascular modulation.

Thus, we tested the hypothesis that angiotensin II levels are intact and contribute to the supine hypertension of autonomic failure. Indeed, our results show that circulating angiotensin II is paradoxically elevated in hypertensive autonomic failure patients compared to healthy subjects, despite similar low renin activity. Given this finding, we performed a randomized, double-blind, crossover study comparing the effects of placebo versus the ARB losartan on supine overnight blood pressure (BP). As a secondary objective, some patients also received the ACE inhibitor captopril on a separate study night, to determine potential mechanisms involved in angiotensin II production. Finally, to further assess the therapeutic potential of these medications for management of autonomic failure, we measured their effect on nocturnal natriuresis and morning orthostatic tolerance.

Methods

This study was approved by the Vanderbilt Investigational Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to enrollment (http://clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00223717).

Study Participants

This study included 11 patients with primary autonomic failure diagnosed with either multiple systems atrophy (MSA, n=5) or pure autonomic failure (PAF, n=6) based on established criteria.(1) All patients had supine hypertension defined as SBP ≥150 mmHg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥90 mmHg.(2) Patients were excluded if they had secondary forms of autonomic failure (i.e. diabetes, amyloidosis) or renal failure. We also studied 10 healthy volunteers matched for age, gender and body mass index (BMI). Healthy volunteers were non-smokers and were excluded if pregnant, had evidence of systemic illness, or were taking medications known to interfere with regulation of BP, blood volume or the RAS.

General Protocol

Autonomic failure patients were admitted to the Clinical Research Center at Vanderbilt University on an inpatient basis. Medications affecting the autonomic nervous system, BP or blood volume were withheld for ≥5 half-lives before admission including fludrocortisone, statins, diuretics, β-blockers, or other antihypertensive medications. Patients were placed on a fixed diet consisting of low monoamine, methylxanthine-free food containing 150 mEq sodium and 70 mEq potassium. Healthy volunteers were studied as outpatients, withheld from methylxanthine-containing products or medications for three days prior to the study, and had 24-hour urinary sodium levels within normal limits. All subjects were screened with a comprehensive medical history, physical examination, 12-lead ECG and routine laboratory tests.

Autonomic Function and Orthostatic Stress Testing

Standardized autonomic function tests were performed including sinus arrhythmia, Valsalva maneuver, hyperventilation, cold pressor and isometric handgrip.(9) BP was measured intermittently with an automated sphygmomanometer cuff (Dinamap, GE Healthcare) and continuously with finger photoplethysmography (Nexfin, BMEYE). Heart rate (HR) was measured by continuous ECG. For orthostatic stress testing, subjects remained supine after an overnight rest and then were asked to stand for 10 minutes, or as long as tolerated. BP and HR were measured in the supine position and again after 1, 3, 5 and 10 minutes of standing with an automated sphygmomanometer (Dinamap). Fasting blood samples were collected at the end of the supine and standing periods for circulating hormone measurements, through an antecubital vein catheter placed at least 30 minutes prior to testing.

Circulating Hormone Measurements

Plasma norepinephrine was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection.(10) Plasma renin activity was measured by conversion of angiotensinogen to angiotensin I using radioimmunoassay (IgG Corporation). Plasma aldosterone was measured using radioimmunoassay analysis (Diagnostics Products Corporation). For statistical analysis, renin activity or aldosterone levels below detection limits (<0.2 ng/ml/hr or <2.5 ng/dl, respectively) were assigned a value of one-half the detection limit. For angiotensin II, blood was collected in a peptidase inhibitor cocktail to prevent in vitro metabolism, and harvested plasma was sent to the Hypertension Core Laboratory at Wake Forest University for analysis using radioimmunoassay (ALPCO Diagnostics, RK-A22) as previously described.(11) The analytical sensitivity for this assay is 1.0 pg/ml, with 8% intra-assay and 12% inter-assay variability. This assay has high cross-reactivity for Ang III and Ang IV metabolites (108% and 96%, respectively).

Overnight Medication Trials

We performed a randomized, double-blind, crossover study comparing the effects of single dose losartan (50 mg, PO) versus placebo on overnight BP in 11 autonomic failure patients. Seven of these patients were also randomized to receive captopril (50 mg, PO) on a separate study night. The primary outcome was the decrease in SBP following drug administration. As secondary endpoints, we examined for changes in nocturnal pressure natriuresis and morning orthostatic tolerance. Medications were administered with 50 mL of tap water at 8:00 PM and ≥2.5 hours after the last meal. Patients were instructed to remain supine throughout the night and BP was measured twice in a row at 2 hour intervals with an automated cuff (Dinamap). At 8:00 AM patients were asked to stand for 10 minutes, with BP and HR measured after 1, 3, 5 and 10 minutes of standing, or as long as tolerated to assess orthostatic tolerance. To determine effects on pressure natriuresis, urine was collected for 12 hours following drug administration. Since these patients often have neurogenic bladder,(1) it is difficult to obtain accurate urine volume measurements. Thus, nocturnal sodium excretion was defined as the ratio of urinary sodium to creatinine, to correct for incomplete bladder emptying. Changes in body weight were also measured as a means to assess overnight volume loss.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (Version 19.0, IBM Corp). A two-tailed alpha level of <0.05 was defined as statistical significance. Differences between autonomic failure patients and healthy subjects were compared by Mann-Whitney U non-parametric analysis. To evaluate changes in overnight SBP we used two-way ANOVA to test for effects of treatment, time and their interaction. To summarize overnight SBP changes, area under the curve (AUC) for the 7 measurements was calculated by the trapezoidal rule (AUCSBP = mean SBP*time). Morning orthostatic tolerance was also calculated as AUC for standing SBP, with comparisons made for patients who could stand after all active medications. Changes in AUC for overnight and morning SBP, body weight and urinary sodium excretion were analyzed by Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Our preliminary data from 3 patients showed a difference in SBP means of 25 mmHg, with standard deviation of difference of 22 mmHg, following placebo versus losartan. Based on these data, we calculated that 10 patients would have 90% power to detect a difference in means between treatments with an alpha level of 0.05 using paired t-test analysis (PS Dupont, Version 3.0.34).

Results

Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

As shown in Table 1, there were no differences in age, BMI or gender between autonomic failure patients and healthy subjects. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia was significantly reduced in autonomic failure suggesting parasympathetic dysfunction. Sympathetic impairment was evident in autonomic failure as indicated by: a) a decrease in SBP during Phase II of Valsalva maneuver; b) absence of BP overshoot during Phase IV of Valsalva maneuver and c) blunted SBP responses to isometric handgrip and cold pressor tests. By definition, autonomic failure patients had higher supine BP compared to healthy subjects, with no significant differences in HR (Table 2). Upright posture produced profound decreases in BP in autonomic failure, with an inadequate compensatory HR increase, indicating failure of baroreflex modulation. Plasma norepinephrine, renin activity and aldosterone significantly increased upon standing in both groups. However, postural norepinephrine increases were blunted in autonomic failure, suggesting reduced ability to engage sympathetic activity.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics and Autonomic Function Testing

| Characteristics | Healthy (n = 10) |

Autonomic Failure (n = 11) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64 ± 3 | 69 ± 2 | 0.197 |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 25.4 ± 1.0 | 24.2 ± 0.6 | 0.199 |

| Gender, female: male | 6:4 | 7:4 | |

| Autonomic Function Tests | |||

| Sinus Arrhythmia ratio | 1.33 ± 0.11 | 1.09 ± 0.03 | 0.006 |

| Valsalva ratio | 1.51 ± 0.09 | 1.16 ± 0.05 | 0.006 |

| Valsalva Phase II ΔSBP, mmHg† | −37 ± 6 | −75 ± 7 | 0.001 |

| Valsalva Phase IV ΔSBP, mmHg | 13 ± 7 | −28 ± 9 | 0.006 |

| Hyperventilation, mmHg | −4 ± 3 | −28 ± 6 | 0.002 |

| Handgrip ΔSBP, mmHg† | 22 ± 7 | 1 ± 3 | 0.035 |

| Cold Pressor ΔSBP, mmHg† | 16 ± 3 | 8 ± 4 | 0.095 |

Values are mean ± SEM.

Blood pressure responses given as change (Δ) compared with baseline. SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Table 2.

Orthostatic Stress Testing and Neurohormonal Profile

| Measurements | Healthy (n = 10) |

Autonomic Failure (n = 11) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthostatic Stress Tests | |||

| Supine (≥ 30 minutes) | |||

| SBP, mmHg | 116 ± 5 | 166 ± 5 | 0.001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 74 ± 4 | 89 ± 3 | 0.005 |

| HR, bpm | 66 ± 4 | 70 ± 4 | 0.512 |

| Standing (1 minute) | |||

| SBP, mmHg | 121 ± 6 | 92 ± 12 | 0.043 |

| DBP, mmHg | 79 ± 3 | 59 ± 6 | 0.015 |

| HR, mmHg | 76 ± 4 | 83 ±5 | 0.353 |

| Δ SBP (standing – supine) | 4 ± 3 | −75 ± 13 | 0.001 |

| Δ DBP (standing – supine) | 4 ± 3 | −30 ± 7 | 0.002 |

| Δ HR (standing – supine) | 10 ± 2 | 15 ± 3 | 0.353 |

| Plasma Norepinephrine, pg/ml | |||

| Supine | 352 ± 65 | 209 ± 50 | 0.113 |

| Upright | 689 ± 61 † | 357 ± 100 † | 0.046 |

| Plasma Renin Activity, ng/ml/hr | |||

| Supine | 0.34 ± 0.13 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.449 |

| Upright | 0.73 ± 0.29 † | 0.32 ± 0.11 † | 0.356 |

| Plasma Aldosterone, ng/dl | |||

| Supine | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 0.684 |

| Upright | 5.7 ± 1.0 † | 5.4 ± 0.8 † | 0.842 |

Values are mean ± SEM.

p < 0.05 versus supine. SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate.

Circulating Ang II Levels and Antihypertensive Effects of Losartan and Captopril

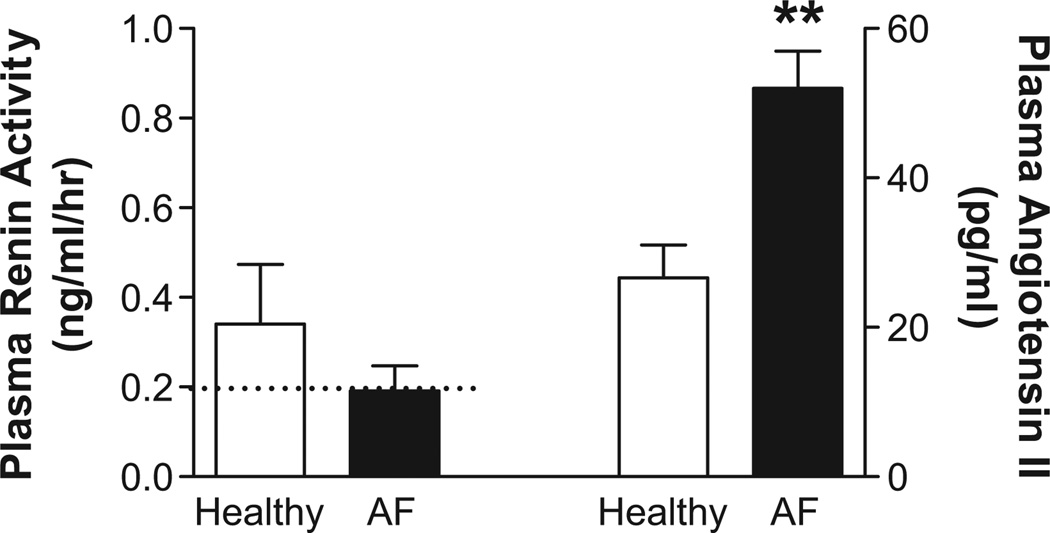

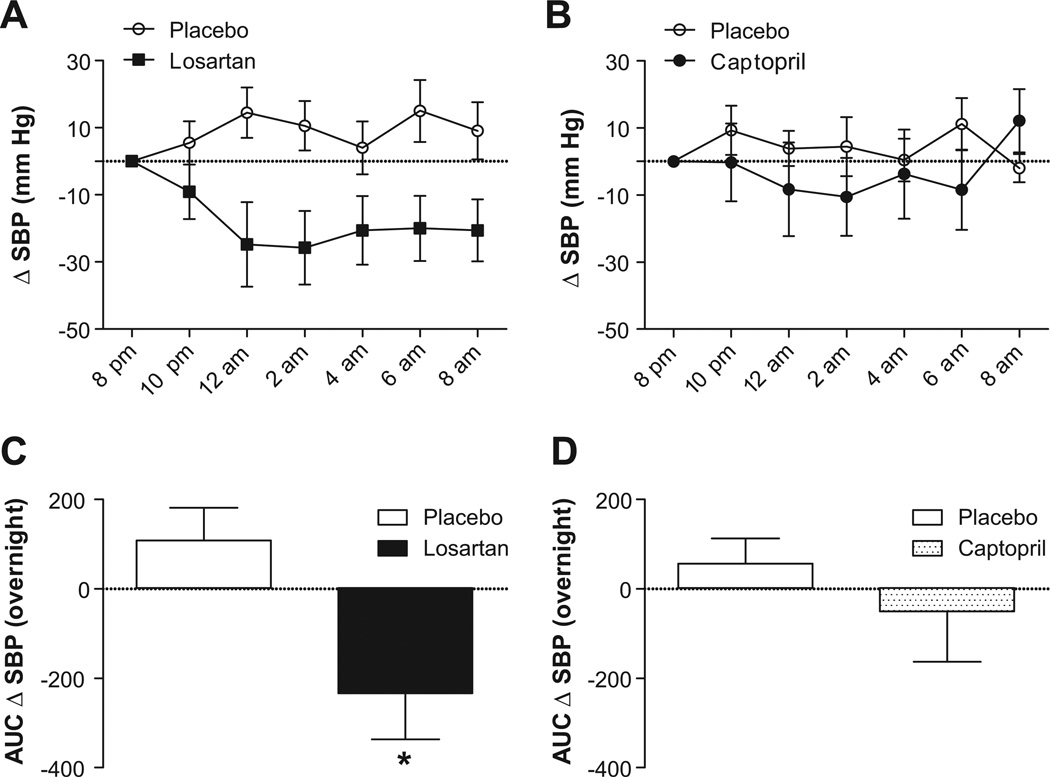

Despite similar low renin activity (Table 2), circulating angiotensin II was paradoxically increased in hypertensive autonomic failure patients compared to healthy subjects (Figure 1; p=0.002). Based on this finding, we assessed whether losartan could reduce supine overnight BP in these patients. All patients completed placebo and losartan treatment arms, with no differences in baseline SBP between study nights (placebo: 164±11 mmHg; losartan: 167±6 mmHg; p=0.799). Losartan maximally decreased SBP by 32±11 mmHg at 6 hours after administration (95% CI: −58 to −6 mmHg, Figure 2), resulting in an average SBP of 135±8 mmHg at this time point. The main treatment effect of losartan was significant (p<0.001, two-way ANOVA; Figure 2A), as was the AUC for SBP changes following losartan versus placebo (p=0.047; Figure 2B). Losartan also significantly lowered DBP at 6 hours (placebo: 6±4 mmHg; losartan: −12±6 mmHg; p=0.015), with no effect on HR (placebo: −4±3 bpm; losartan: −4±2 bpm; p=0.684).

Figure 1. Paradoxic Elevations in Angiotensin II in Autonomic Failure.

Despite similar renin activity, plasma angiotensin II was significantly higher in autonomic failure patients with supine hypertension relative to matched healthy subjects. ** p = 0.002 versus healthy; AF, autonomic failure; dashed line, detection limit for renin activity.

Figure 2. Effects of Losartan and Captopril on Blood Pressure in Autonomic Failure.

Effect of single dose losartan (50 mg, PO; n=11) or captopril (50 mg, PO; n=7) administered at 8:00 PM on overnight systolic blood pressure (SBP) in autonomic failure patients with supine hypertension. Losartan produced significant decreases in SBP compared to placebo as summarized by (A) changes in SBP over time and (B) area under the curve (AUC) for SBP. There was no effect of captopril on overnight SBP in these patients (C, D).

The ACE inhibitor captopril was also administered to 7 of these patients. There was a tendency towards higher baseline SBP on the placebo versus captopril night that did not reach statistical significance (176±11 and 154±7, respectively; p=0.109). Captopril produced a maximal 11±12 mmHg decrease in overnight SBP (95% CI: −39 to 17 mmHg), which was not different from placebo (−4±8 mmHg, 95% CI: −23 to 14 mmHg; p=0.1508, two-way ANOVA, Figure 2C; p=0.1094, AUC for overnight SBP, Figure 2D). There was also no significant effect of captopril on DBP (placebo: 5±5 mmHg; captopril: −4±7 mmHg; p=0.318) or HR (placebo: −4±3 bpm; captopril: −6±3 bpm; p=0.902).

Effect of Ang II Blockade on Urinary Sodium Excretion and Morning Orthostatic Tolerance

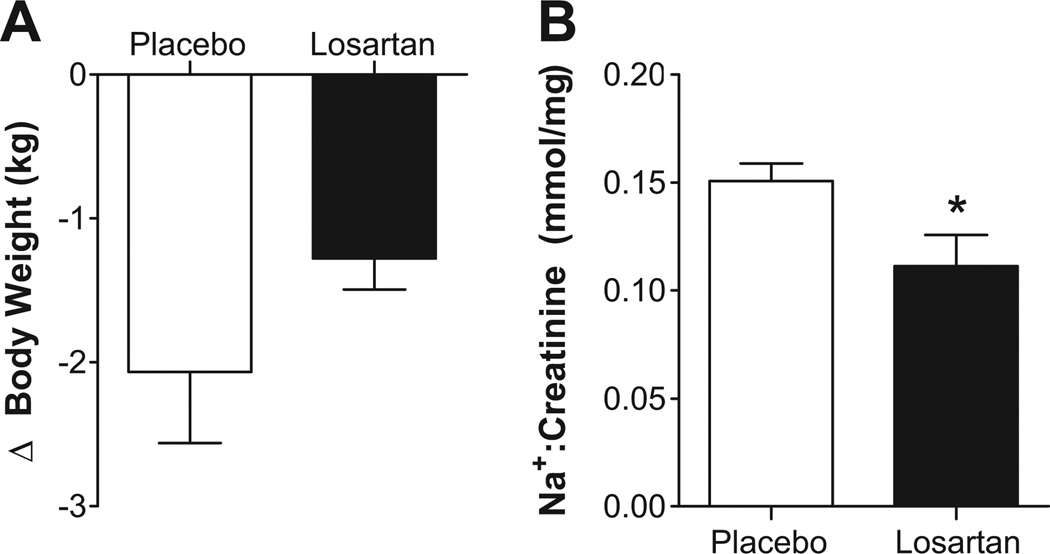

Losartan did not significantly alter body weight compared to placebo (Figure 3A; p=0.249); however, urinary sodium excretion was reduced following losartan (Figure 3B; p=0.046). Of the 11 patients studied, only 7 were able to stand after both treatment arms. The AUC for morning SBP was not significantly different following placebo versus losartan (530±194 versus 404±163 mmHg*min, respectively; p=0.687). Captopril did not produce significant changes in either body weight (placebo: −1.7±0.8 kg; captopril: −1.2±0.4 kg; p=0.127) or nocturnal sodium excretion (placebo: 0.145±0.119 mmol/mg; captopril: 0.119±0.009 mmol/mg; p=0.1364). In the 5 patients that could stand after both placebo and captopril treatments, there was no difference in the AUC for morning SBP (527±248 placebo versus 516±187 mmHg*min captopril; p=0.8125).

Figure 3. Effect of Losartan on Nocturnal Volume Loss and Sodium Excretion.

(A) There was no significant effect of losartan on changes in body weight, a measure of night-time volume loss, in hypertensive autonomic failure patients. (B) Losartan significantly reduced nocturnal urinary sodium (Na+) excretion in these patients. * p = 0.046.

Discussion

The present study provides evidence that in autonomic failure patients with supine hypertension: (a) circulating angiotensin II is paradoxically elevated compared to healthy subjects, despite low and often undetectable renin activity; (b) AT1 receptor blockade with losartan, but not ACE inhibition with captopril, effectively lowered overnight BP; (c) losartan decreased nocturnal urinary sodium excretion to improve pressure natriuresis, with no effect of captopril; and (d) neither losartan nor captopril worsened morning orthostatic tolerance. These findings suggest that mechanisms independent of renin activity, and perhaps ACE, are involved in angiotensin II formation in autonomic failure in the context of supine hypertension. While the source is still under investigation, these studies show that elevations in angiotensin II can contribute to supine hypertension, and provide rationale for the use of ARBs in the management of autonomic failure.

We and others have shown low and unresponsive renin activity in autonomic failure, (7;8) and therefore disregarded a contribution of the RAS to hypertension in these patients. In agreement with previous findings, renin activity was below detection limits in 73% of autonomic failure patients compared to 50% of healthy subjects. Autonomic failure is associated with loss of renin immunoreactivity in juxtaglomerular cells in autopsied kidneys suggesting loss of sympathetic innervation for renin release.(7) However, the role of norepinephrine itself in renin release is more complicated, as patients with dopamine β-hydroxylase deficiency, with intact innervation but no norepinephrine, have normal renin activity. Despite often undetectable renin, angiotensin II was increased in autonomic failure, to levels seen in severe essential hypertension (12), and higher than those observed in hypertensive subjects responsive to ARBs (13). These findings raise the possibility that renin-independent mechanisms are involved in angiotensin II formation in autonomic failure. Several such mechanisms have been proposed, including alternate enzymes for angiotensinogen cleavage such as cathepsins, tonin and chymase (14); prorenin activating the prorenin receptor to generate angiotensin II independent of renin activation (15); renin-independent cleavage of angiotensin-(1–12) to generate angiotensin II (16); and tissue-derived renin to generate angiotensin II for secretion into the circulation (17). Autonomic failure may represent a model where these alternate pathways could be investigated and this is an area of active research in our laboratory.

Even if the source is not yet known, this study provides evidence that angiotensin II contributes to support of supine BP in autonomic failure. Losartan provides high affinity, selective blockade of the AT1 receptor to directly inhibit angiotensin II effects.(18) Losartan produces little effect on BP in healthy subjects in sodium balance.(19) In essential hypertension, single dose losartan modestly reduces pressure (5 to 15 mmHg),(20) and chronic dosing produces approximate 10 to 20 mmHg reductions in SBP.(18) The magnified hypotensive effect in autonomic failure (>30 mmHg) is likely explained by lack of baroreflex buffering.

The lack of captopril effect may suggest that angiotensin II formation is independent of ACE activity in autonomic failure. Previous studies show that acute captopril (50 mg) lowers supine pressure by 12 to 16 mmHg in autonomic failure,(21) an effect similar in magnitude to our observations. However, the previous study included patients with and without hypertension and did not have a placebo comparator arm. Furthermore, since depressor responses did not correlate with renin activity it was concluded that captopril effects were due to non-specific increases in vasodilatory peptides, rather than direct angiotensin II effects.(21) It could be argued that higher dose captopril could have proven more effective; however, first dose captopril produces exaggerated hypotensive effects, particularly in elderly hypertensive patients.(22;23) The lower baseline SBP prior to captopril administration is not likely due to carryover effects as medications were randomized with appropriate washout between studies. While the lower baseline pressure could result in a floor effect, we routinely observe that antihypertensive medications lower SBP <140 mmHg in autonomic failure patients.(24;25)

The ideal treatment for autonomic failure should not only control night-time hypertension, but also reduce pressure natriuresis to improve morning orthostatic hypotension. Non-pharmacologic head-up tilt is one such approach (26); however, the degree of tilt required in patients with severe hypertension limits this approach. Several medications reduce supine hypertension in autonomic failure such as nitroglycerin patch, sildenafil, and clonidine.(24;25;27) However, none of these reduce nocturnal pressure natriuresis and improve morning orthostatic tolerance. In this study, losartan effectively lowered nocturnal pressure and urinary sodium excretion. This contrasts effects of chronic losartan to increase sodium and water excretion in essential hypertension,(18) by blocking renal effects of angiotensin II effects. However, acute losartan does not alter sodium excretion in hypertensive subjects.(20;28) Unfortunately, we were unable to demonstrate an improvement in morning orthostatic tolerance following losartan. This could be attributed to residual hypotensive effects, since the maximal SBP decrease occurred at 6 hours after administration. While losartan could be given earlier in the night to prevent morning reductions in BP, further studies are needed before recommending this for patient management.

There are potential limitations to this study. First, the angiotensin II radioimmunoassay shows cross-reactivity for angiotensin III and IV metabolites. However, previous studies show that angiotensin II is the predominant species in venous blood from humans.(29) In addition, the antihypertensive effects of losartan provide functional evidence for presence of biologically significant levels of angiotensin II. Second, this study included a small number of subjects, especially for captopril. All subjects could not receive captopril based on medication allergies or contraindications. However, since these studies were powered to detect differences in overnight SBP, we would need 66 patients to have 80% power to detect a difference in means between captopril and placebo based on the present data showing a mean difference of 7 mmHg and a standard deviation of difference of 20 mmHg. In the patients receiving captopril, we still observed a highly significant BP lowering effect of losartan, suggesting angiotensin II is important despite no effect of ACE inhibition. Finally, due to the small number of patients, a direct comparison between MSA and PAF patients was not made. This will be investigated in future studies given that supine hypertension is driven by different mechanisms in these patients. While hypertension in MSA is supported by residual sympathetic tone,(30) it is driven by increased vascular resistance in PAF.(31) Importantly, angiotensin II could contribute to hypertension in either MSA or PAF, as this peptide increases sympathetic and vascular tone.

Perspectives

Based on the finding for low renin activity,(7;8) therapies targeting angiotensin II are not commonly used for treatment of supine hypertension in autonomic failure, despite having potential benefit for cardiovascular end organ damage. The findings in the present study, however, suggest that losartan, and potentially other ARBs, should be considered in management of these patients. Whether losartan provides long-term benefit is unclear and will need to be addressed in future studies. While primary autonomic failure is a relatively rare condition, these patients provide the unique opportunity to study BP regulation, and the development of hypertension, in the absence of autonomic and traditional renin influences. The identification of mechanisms driving paradoxic elevations in BP in autonomic failure will have important implications for management of these patients. These findings may also improve our understanding of essential hypertension, particularly in the context of low renin forms of the disease and in elderly patients with concomitant orthostatic hypotension.

Novelty and Significance.

1. What is new:

-

■

Circulating angiotensin II is elevated in autonomic failure patients with supine hypertension, despite often undetectable renin activity. The ARB losartan effectively lowers overnight BP in these patients.

2. What is Relevant:

-

■

These findings have important implications for understanding mechanisms of hypertension in autonomic failure, and for treatment of these patients.

-

■

Autonomic failure provides unique insight into BP regulation in the absence of autonomic influences. Thus, these results may also impact our understanding of hypertension in general.

3. Summary:

-

■

Angiotensin II contributes to the hypertension of autonomic failure, and losartan can effectively reduce overnight BP and pressure natriuresis these patients, without worsening morning orthostatic tolerance.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our patients and healthy volunteers.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants: P01HL056693, 5U54NS065736 and UL1TR000445. A.C.A. is supported by American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship 11POST7330010.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest and Disclosures: I.B. is consultant to Chelsea Therapeutics, and receives financial support for an investigator-initiated study from Forest Laboratories through Vanderbilt University.

Reference List

- 1.Kaufmann H. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, pure autonomic failure and multiple system atrophy. Clin Auton Res. 1996;6:125–126. doi: 10.1007/BF02291236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biaggioni I, Robertson RM. Hypertension in orthostatic hypotension and autonomic dysfunction. Cardiol Clin. 2002;20:291–301. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(01)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vagaonescu TD, Saadia D, Tuhrim S, Phillips RA, Kaufmann H. Hypertensive cardiovascular damage in patients with primary autonomic failure. Lancet. 2000;355:725–726. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05320-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garland EM, Gamboa A, Okamoto L, Raj SR, Black BK, Davis TL, Biaggioni I, Robertson D. Renal impairment of pure autonomic failure. Hypertension. 2009;54:1057–1061. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.136853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrario CM. Role of angiotensin II in cardiovascular disease therapeutic implications of more than a century of research. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2006;7:3–14. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2006.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catanzaro DF, Frishman WH. Angiotensin receptor blockers for management of hypertension. South Med J. 2010;103:669–673. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181e1e2da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biaggioni I, Garcia F, Inagami T, Haile V. Hyporeninemic normoaldosteronism in severe autonomic failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:580–586. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.3.7680352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baser SM, Brown RT, Curras MT, Baucom CE, Hooper DR, Polinsky RJ. Beta-receptor sensitivity in autonomic failure. Neurology. 1991;41:1107–1112. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.7.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Low PA. Testing the autonomic nervous system. Semin Neurol. 2003;23:407–421. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-817725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein DS, Eisenhofer G, Stull R, Folio CJ, Keiser HR, Kopin IJ. Plasma dihydroxyphenylglycol and the intraneuronal disposition of norepinephrine in humans. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:213–220. doi: 10.1172/JCI113298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, Diz DI, Gallagher PE. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111:2605–2610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swales JD, Thurston H. Plasma renin and angiotensin II measurement in hypertensive and normal subjects: correlation of basal and stimulated states. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1977;45:159–163. doi: 10.1210/jcem-45-1-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell DJ, Krum H, Esler MD. Losartan increases bradykinin levels in hypertensive humans. Circulation. 2005;111:315–320. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153269.07762.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genest J, Cantin M, Garcia R, Thibault G, Gutkowska J, Schiffrin E, Kuchel O, Hamet P. Extrarenal angiotensin-forming enzymes. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1983;5:1065–1080. doi: 10.3109/10641968309048842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen G, Delarue F, Burckle C, Bouzhir L, Giller T, Sraer JD. Pivotal role of the renin/prorenin receptor in angiotensin II production and cellular responses to renin. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1417–1427. doi: 10.1172/JCI14276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagata S, Kato J, Sasaki K, Minamino N, Eto T, Kitamura K. Isolation and identification of proangiotensin-12, a possible component of the renin-angiotensin system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bader M. Tissue renin-angiotensin-aldosterone systems: Targets for pharmacological therapy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:439–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McIntyre M, Caffe SE, Michalak RA, Reid JL. Losartan, an orally active angiotensin (AT1) receptor antagonist: a review of its efficacy and safety in essential hypertension. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;74:181–194. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)82002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burnier M, Waeber B, Brunner HR. Clinical pharmacology of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan potassium in healthy subjects. J Hypertens Suppl. 1995;13:S23–S28. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199507001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg MR, Bradstreet TE, McWilliams EJ, Tanaka WK, Lipert S, Bjornsson TD, Waldman SA, Osborne B, Pivadori L, Lewis G. Biochemical effects of losartan, a nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonist, on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1995;25:37–46. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kooner JS, Raimbach S, Bannister R, Peart S, Mathias CJ. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition lowers blood pressure in patients with primary autonomic failure independently of plasma renin levels and sympathetic nervous activity. J Hypertens Suppl. 1989;7:S42–S43. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198900076-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodsman GP, Isles CG, Murray GD, Usherwood TP, Webb DJ, Robertson JI. Factors related to first dose hypotensive effect of captopril: prediction and treatment. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;286:832–834. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6368.832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansen PA, De Vries OO, De Rooy SE, Raymakers JA. Blood pressure reduction after the first dose of captopril and perindopril. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1574–1575. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibao C, Gamboa A, Abraham R, Raj SR, Diedrich A, Black B, Robertson D, Biaggioni I. Clonidine for the treatment of supine hypertension and pressure natriuresis in autonomic failure. Hypertension. 2006;47:522–526. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000199982.71858.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gamboa A, Shibao C, Diedrich A, Paranjape SY, Farley G, Christman B, Raj SR, Robertson D, Biaggioni I. Excessive nitric oxide function and blood pressure regulation in patients with autonomic failure. Hypertension. 2008;51:1531–1536. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.105171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ten Harkel AD, Van Lieshout JJ, Wieling W. Treatment of orthostatic hypotension with sleeping in the head-up tilt position, alone and in combination with fludrocortisone. J Intern Med. 1992;232:139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordan J, Shannon JR, Pohar B, Paranjape SY, Robertson D, Robertson RM, Biaggioni I. Contrasting effects of vasodilators on blood pressure and sodium balance in the hypertension of autonomic failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:35–42. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fauvel JP, Velon S, Berra N, Pozet N, Madonna O, Zech P, Laville M. Effects of losartan on renal function in patients with essential hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;28:259–263. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199608000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Semple PF, Boyd AS, Dawes PM, Morton JJ. Angiotensin II and its heptapeptide (2-8), hexapeptide (3-8), and pentapeptide (4-8) metabolites in arterial and venous blood of man. Circ Res. 1976;39:671–678. doi: 10.1161/01.res.39.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shannon JR, Jordan J, Diedrich A, Pohar B, Black BK, Robertson D, Biaggioni I. Sympathetically mediated hypertension in autonomic failure. Circulation. 2000;101:2710–2715. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.23.2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kronenberg MW, Forman MB, Onrot J, Robertson D. Enhanced left ventricular contractility in autonomic failure: assessment using pressure-volume relations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:1334–1342. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]