Abstract

Syncope is a common clinical condition occurring even in healthy people without manifest cardiovascular disease. The purpose of this study was to determine the role of cardiac output and sympathetic vasoconstriction in neurally mediated (pre)syncope. Twenty-five subjects (age 15–51) with no history of recurrent syncope but who had presyncope during 60 deg upright tilt were studied; 10 matched controls who completed 45 min tilting were analysed retrospectively. Beat-to-beat haemodynamics (Modelflow), muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) and sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity (MSNA–diastolic pressure relation) were measured. MSNA, haemodynamic responses and baroreflex sensitivity during early tilting were not different between presyncopal subjects and controls. Hypotension was mediated by a drop in cardiac output in all presyncopal subjects, accompanied by a decrease in total peripheral resistance in 16 of them (64%, group A). In the other 9 subjects, total peripheral resistance was well maintained even at presyncope (36%, group B). Cardiac output was smaller (3.26 ± 0.34 (SEM) vs. 5.02 ± 0.40 l min−1, P= 0.01), while total peripheral resistance was greater (1327 ± 117 vs. 903 ± 80 dyn s cm−5, P < 0.01) in group B than group A at presyncope. The steeper fall in cardiac output in group B was due to a drop in heart rate. MSNA decreased rapidly at presyncope after the onset of hypotension. Thus, a moderate fall in cardiac output with coincident vasodilatation or a marked fall in cardiac output with no changes in peripheral vascular resistance may contribute to (pre)syncope. However, an intrinsic impairment of vasomotor responsiveness and sympathetic baroreflex function is not the cause of neurally mediated (pre)syncope in this population.

Key points

Syncope is a common clinical condition occurring even in healthy people without manifest cardiovascular disease; we determined the role of cardiac output and sympathetic vasoconstriction in neurally mediated (pre)syncope.

Our data showed that a moderate fall in cardiac output with coincident vasodilatation occurred in the majority (64%) of the presyncopal subjects, while a marked fall in cardiac output, driven predominantly by a decrease in heart rate, with no changes in total peripheral resistance at presyncope, occurred in a smaller (36%) subset.

Sympathetic withdrawal occurred late, after the onset of hypotension.

Sympathetic vasoconstriction and baroreflex sensitivity during symptom-free upright posture were well preserved and, thus, an intrinsic impairment of sympathetic neural control and vasomotor responsiveness was not the cause of neurally mediated (pre)syncope in this population.

These results help us better understand the mechanisms for syncope in humans.

Introduction

Syncope is a common clinical condition affecting up to 40% of otherwise healthy people (Ganzeboom et al. 2006; Serletis et al. 2006), especially young women (Robertson, 1999). Despite this wide impact, our fundamental knowledge about syncope has not changed greatly since the earliest description by Sir Thomas Lewis in 1932 (Lewis, 1932).

Based on current conventional wisdom, loss of sympathetic tone (Wallin & Sundlof, 1982; Dietz et al. 1997; Morillo et al. 1997; Mosqueda-Garcia et al. 1997) with relaxation of vascular resistance (Lewis, 1932; Barcroft et al. 1944; Weissler et al. 1957; Epstein et al. 1968) is thought to play a major role in neurally mediated syncope. Profound vasodilatation in the forearm has indeed been observed during true syncope (Lewis, 1932; Barcroft et al. 1944; Weissler et al. 1957). However, an earlier study showed that systemic vascular resistance remained above baseline levels, while forearm vascular resistance decreased by 30% at syncope (Murray et al. 1968). It is possible that the profound vasodilatation in the forearm may overestimate the total body vascular resistance response during syncope (Hirsch et al. 1989).

This notion seems to be supported by the findings of Cooke et al. (2009) and Vaddadi et al. (2010). For example, with the microneurographic technique, Cooke et al. (2009) found that withdrawal of muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) was not a prerequisite for (pre)syncope despite significant decreases of arterial pressure in healthy individuals. Vaddadi et al. (2010) also found that MSNA persisted during presyncope in the majority of patients with a history of recurrent syncope. Conversely, investigations in recurrent syncopal patients demonstrated that the initial reduction in blood pressure (BP) during orthostatic syncope was mainly driven by a fall in cardiac output of approximately 50%, with coincident vasodilatation in a subset of patients (Gisolf et al. 2004; Verheyden et al. 2007, 2008). Whether similar observations can be made in healthy humans is unclear. In addition, whether a decrease in sympathetic vasoconstriction is necessary for occurrence of (pre)syncope in healthy individuals needs to be determined. This knowledge would be essential to derive pathophysiological-based therapies for this challenging condition.

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the physiological role of cardiac output and sympathetic vasoconstriction in presyncope in people without manifest cardiovascular disease. We determined specifically: (1) the time course of changes in vasomotor sympathetic activity and haemodynamics prior to and at presyncope; (2) whether sympathetic withdrawal is related to a decrease in systemic vascular resistance during presyncope; and (3) whether sympathetic neural control in the early (i.e. symptom-free) stage of orthostasis is associated with the test outcome (i.e. presyncope).

Methods

Participants

This study involved the retrospective analysis of data from previous research investigating sex differences in BP control and orthostatic tolerance (Fu et al. 2005, 2009). All 25 subjects who developed presyncope during a tilt-table test with microneurographic recordings were included. Ten age-, sex- and body mass index-matched subjects who completed a 45 min 60 deg upright tilt without presyncope served as controls. Subjects were recruited from the Dallas–Fort Worth area between 2004 and 2009. No subject smoked, used recreational drugs or had significant medical problems. Women taking oral contraceptives were excluded. None had a history of recurrent syncope. Subjects were screened with a medical history, physical examination and 12-lead electrocardiogram. All subjects signed an informed consent form on the experimental protocol, which was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas. The study followed guidelines set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. A summary of the descriptive data for presyncopal and non-presyncopal subjects is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Presyncopal subjects | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Both CO and TPR decrease (group A, n= 16) | Only CO decrease (group B, n= 9) | Non-presyncopal controls (n= 10) |

| Age (year) | 32 ± 3 | 27 ± 3 | 30 ± 2 |

| Height (cm) | 169 ± 2 | 166 ± 2 | 168 ± 2 |

| Weight (kg) | 67 ± 3 | 65 ± 3 | 66 ± 2 |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 24 ± 1 | 24 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 |

| Men/women (n) | 4/12 | 0/9 | 2/8 |

| Women EFP/MLP (n) | 6/6 | 4/5 | 2/6 |

| Oestradiol (pg ml−1) | 61.4 ± 19.7 | 60.8 ± 18.6 | 75.1 ± 17.3 |

| Progesterone (ng ml−1) | 4.5 ± 1.7 | 5.6 ± 2.2 | 8.4 ± 2.5 |

| Tilt time (min) | 23 ± 3* | 25 ± 5* | 45 ± 0 |

Values are mean ± SEM. CO, cardiac output. TPR, total peripheral resistance. BMI, body mass index. EFP, early follicular phase. MLP, mid-luteal phase.

P < 0.05 vs. controls.

Measurements

Muscle sympathetic nerve activity

MSNA signals were obtained with the microneurographic technique (Wallin et al. 1974; Vallbo et al. 1979). Briefly, a recording electrode was placed in the peroneal nerve at the popliteal fossa, and a reference electrode was placed subcutaneously 2–3 cm from the recording electrode. The nerve signals were amplified (gain 70,000–160,000), band-pass filtered (700–2000 Hz), full-wave rectified and integrated with a resistance-capacitance circuit (time constant 0.1 s). Criteria for adequate MSNA recordings included: (1) pulse synchrony; (2) facilitation during the hypotensive phase of the Valsalva manoeuver, and suppression during the hypertensive overshoot after release; (3) increases in response to breath holding; and (4) insensitivity to emotional stimuli (Wallin et al. 1974).

Heart rate and blood pressure

Heart rate was monitored from lead II of the electrocardiogram (Hewlett-Packard), and beat-to-beat BP was derived by finger photoplethysmograph (Portapres). Arm-cuff BP was measured by electrosphygmomanometry (Suntech) with a microphone placed over the brachial artery to detect Korotkoff sounds. Finger BP was calibrated by arm BP in the supine position for each subject.

Haemodynamic variables

Beat-to-beat cardiac output was derived from the Modelflow method (Jellema et al. 1999) and calibrated by the acetylene rebreathing technique (Triebwasser et al. 1977), so that supine Modelflow cardiac output was made equal to the supine acetylene cardiac output for each subject. We did not calibrate cardiac output during upright tilt. However, cardiac output measured using Modelflow analysis agreed well with that measured by the acetylene rebreathing technique during tilting in this study (R= 0.74, P < 0.01). Cardiac output was normalized by body surface area as cardiac index. Beat-to-beat total peripheral resistance was calculated as the quotient of mean arterial pressure and Modelflow cardiac output multiplied by 80 (expressed as dyn s cm−5), while beat-to-beat mean BP was derived from the Beatfast Modelflow program (BeatScope).

Protocol

The experiment was performed in the morning or afternoon at least 2 h after a light breakfast or lunch, and at least 48 h after the last caffeinated or alcoholic beverage in a quiet, environmentally controlled laboratory with an ambient temperature of ∼25°C. Twelve of the 29 female subjects were tested in the early follicular phase (1 to 4 days after the onset of menstruation, when both oestrogen and progesterone are low) and 17 females were tested in the mid-luteal phase (19 to 22 days, when both hormones are high) of the menstrual cycle. After ≥30 min of quiet rest in the supine position, baseline data were collected for 6 min. The subject was then tilted passively to 60 deg upright for 45 min or until presyncope. After that, the subject was returned to the supine position for recovery.

Presyncope was defined as a decrease in systolic BP to <80 mmHg; a decrease in systolic BP to <90 mmHg associated with symptoms of lightheadedness, nausea, sweating or diaphoresis; or progressive symptoms of presyncope accompanied by a request from the subject to discontinue the test (Fu et al. 2004).

Data analysis

MSNA signals were identified by a computer program (Cui et al. 2001) and confirmed by an experienced microneurographer. The integrated neurogram was normalized by assigning a value of 100 to the largest amplitude of a sympathetic burst during the 6 min supine baseline. All bursts for that trial were then normalized against that value (Halliwill, 2000). Burst area of the integrated neurogram, systolic and diastolic BP, and R-R interval were measured simultaneously on a beat-to-beat basis. The number of bursts per minute (burst frequency), the number of bursts per 100 heartbeats (burst incidence) and the sum of the integrated burst area per minute (total activity) were used as quantitative indexes.

Assessments of sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity

Sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity was assessed using the slope of the linear correlation between total activity and diastolic BP during spontaneous breathing in the supine position and during upright tilt as previously described (Fu et al. 2006, 2009). To perform a linear regression, values for total activity were averaged over 3 mmHg diastolic BP bins. A statistical weighting procedure was adopted; each data point was entered once for each heart beat in the bin, and total activity was expressed as arbitrary units per heart beat (i.e. a.u. beat−1) (Kienbaum et al. 2001; Fu et al. 2006, 2009).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data during baseline were averaged for 6 min. During upright tilt, data were collected and averaged from the 2nd to the 3rd min (early tilting, symptom-free stage), and in 20 s time intervals over the last 3 min prior to returning to supine either because of completion of 45 min tilting or the development of presyncope.

Physical characteristics between groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Responses during tilting between groups were compared using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA. The Holm–Sidak method was used post hoc for multiple comparisons. The relationship between total activity and diastolic pressure in the supine and upright positions was determined for each subject by least-squares linear regression analysis, and the slopes were compared using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA. All statistical analyses were performed with a computer-based analysis program (SigmaStat, SPSS). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Subject characteristics and supine variables

All subjects had a decrease in cardiac output on moving from supine to upright, and cardiac output was not different between groups during early tilting. Sixteen of 25 presyncopal subjects (64%, group A) had decreases in both cardiac output and total peripheral resistance prior to and during presyncope, while 9 of them (36%, group B) had a decrease in cardiac output only with no changes in total peripheral resistance. We separated presyncopal subjects into two groups because we wanted to determine the relative contribution of cardiac output and sympathetic vasoconstriction in neurally mediated (pre)syncope. The cut-off for the decrease in total peripheral resistance was >5% drop at presyncope when compared to 180 s prior to presyncope. Endogenous circulating oestradiol and progesterone levels did not differ among groups (Table 1, ANOVA P= 0.56 for oestradiol and 0.29 for progesterone). Upright tilt duration was shorter in presyncopal subjects than in controls, but did not differ between group A and group B (Table 1).

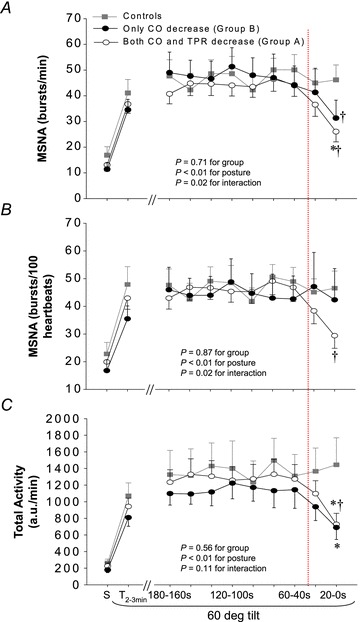

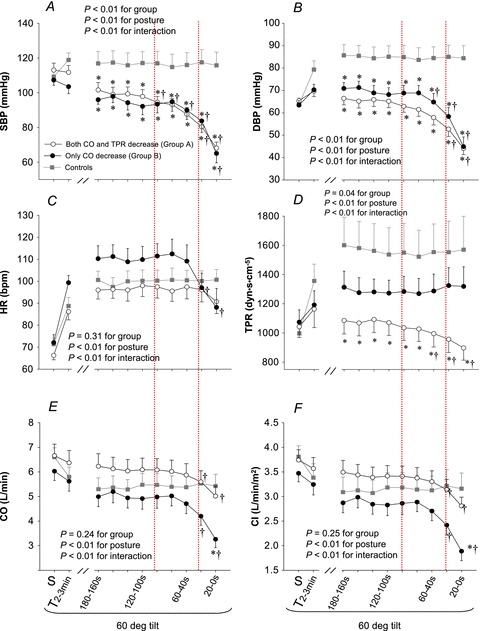

Presyncopal subjects from group A and group B had similar supine MSNA and haemodynamic variables compared with controls (Figs 1 and 2).

Figure 1. MSNA burst frequency (A), burst incidence (B) and total activity (C) responses during tilting.

S, supine. T2−3min, between the 2nd and 3rd min of 60 deg tilt. a.u., arbitrary unit. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. controls at the same time point. †P < 0.05 vs. 180 s within groups. Dotted line indicates that MSNA started to decrease in presyncopal subjects.

Figure 2. Systolic blood pressure (SBP, A), diastolic blood pressure (DBP, B), heart rate (HR, C), total peripheral resistance (TPR, D), cardiac output (CO, E) and cardiac index (CI, F) responses during tilting.

S, supine. T2−3min, between the 2nd and 3rd min of tilting. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. controls at the same time point. †P < 0.05 vs. 180 s within groups. Dotted lines indicate that haemodynamics started to decrease progressively (left dotted line) and then rapidly (right dotted line) in presyncopal subjects.

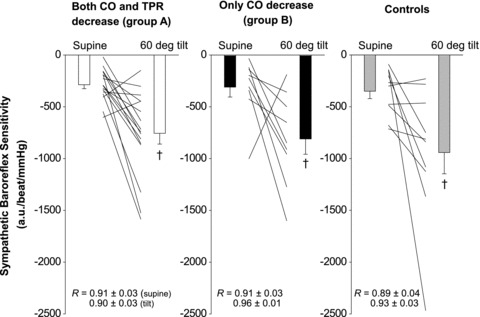

Early tilting (between 2nd and 3rd minute of tilt)

None of the subjects showed any signs of presyncope during early (symptom-free) tilting. MSNA increased from supine to upright; the responses were not different between groups (Fig. 1). Sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity also increased during early tilting; the responses were similar between groups (Fig. 3; ANOVA P < 0.05 for posture, 0.48 for groups and 0.87 for interaction). Systolic BP was maintained and diastolic BP increased during early tilting (Fig. 2A and B). Cardiac output and cardiac index decreased, while heart rate and total peripheral resistance increased from supine to upright (Fig. 2C–F).

Figure 3. Sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity in the supine position and during early tilting (i.e. between the 2nd and 3rd min).

a.u., arbitrary unit. Both individual and mean ± SEM data were presented. †P < 0.05 vs. supine within groups.

Lead-up to presyncope (last 3 min of tilt)

There was a large individual variability in MSNA responses; some subjects had a clear sympathetic withdrawal starting 60 or 40 s before presyncope, while others had the sympathetic withdrawal 20 s before presyncope (Fig. 4). As a group, MSNA decreased rapidly at presyncope, much later than the initial decrease in BP.

Figure 4.

Original tracings of blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR) and muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) in the supine position, and a few minutes before and at presyncope from two presyncopal subjects who had different responses.

Group A (fall in cardiac output and total peripheral resistance)

Presyncopal subjects in group A had similar MSNA responses compared to controls up to 60 s before presyncope (Fig. 1). Systolic BP decreased progressively 100 s and then rapidly 20 s prior to presyncope, while diastolic BP decreased 40 s prior to presyncope (Fig. 2A and B). Heart rate remained unchanged before and during presyncope (Fig. 2C). Total peripheral resistance was lower in presyncopal subjects than controls, and it decreased 60 s before presyncope (Fig. 2D). Cardiac output and cardiac index decreased 40 s before presyncope (Fig. 2E and F). Compared to 180 s prior to presyncope, cardiac output/index decreased by about 20% at presyncope.

Group B (fall in cardiac output only)

Presyncopal subjects in group B had similar MSNA responses compared to controls up to 60 s before presyncope (Fig. 1). Interestingly, both MSNA burst frequency and total activity decreased rapidly (Fig. 1A and C), while burst incidence remained unchanged at presyncope (Fig. 1B). BP was lower in presyncopal subjects compared to controls some minutes before presyncope, and BP decreased rapidly 40 s before presyncope (Fig. 2A and B). Heart rate tended to be greater in presyncopal subjects compared to controls some minutes before presyncope, and it decreased 40 s prior to presyncope (Fig. 2C). Total peripheral resistance remained unchanged before and even during presyncope (Fig. 2D). There appeared to be a dissociation between sympathetic activity and total peripheral resistance at presyncope in presyncopal subjects, namely, decreases in MSNA burst frequency and total activity with no changes in total peripheral resistance (Figs 1 and 2D). Cardiac output and cardiac index decreased 40 s before presyncope (Fig. 2E and F). Compared to 180 s prior to presyncope, cardiac output and cardiac index decreased by approximately 35% at presyncope.

Taken together, presyncopal subjects in group A had a moderate fall in cardiac output accompanied by a progressive decrease in total peripheral resistance, while presyncopal subjects in group B had a marked fall in cardiac output, driven predominantly by a decrease in heart rate, with no changes in total peripheral resistance prior to presyncope. MSNA withdrawal occurred late, after the onset of systemic hypotension in both groups.

Discussion

Our major findings are that: (1) a moderate fall in cardiac output with coincident vasodilatation occurred in the majority (64%) of the presyncopal subjects; (2) a marked fall in cardiac output, driven predominantly by a decrease in heart rate with no changes in total peripheral resistance at presyncope occurred in a smaller (36%) subset; (3) MSNA withdrawal occurred late, after the onset of hypotension; and (4) sympathetic vasoconstriction and baroreflex sensitivity during symptom-free tilting were well preserved and, thus, an intrinsic impairment of sympathetic neural control and vasomotor responsiveness was not the cause of neurally medicated (pre)syncope in this population.

Role of cardiac output in presyncope

We found that cardiac output started to decrease 40 s prior to presyncope, and decreased by approximately 20% in the majority and about 35% in the smaller subset at presyncope compared to that of 180 s before presyncope. These results are consistent with the findings of other investigators (Jardine et al. 2002; Verheyden et al. 2007, 2008). In this study, the decrease in cardiac output was driven predominantly by a decrease in heart rate in the smaller subset. However, Weissler et al. (1957) showed that syncope progressed with a similar decrease in cardiac output despite the absence of bradycardia after atropine injection compared to non-atropinized subjects, and the authors concluded that bradycardia did not appear to be the limiting factor in restricting cardiac output. In the study of Weissler et al., syncope was induced by administration of sodium nitrite in the majority (80% of the subjects). Sodium nitrite can cause profound venodilatation and excessive venous pooling in the legs during tilting. In the face of a marked decrease in venous return to the heart, increases in heart rate alone by atropine cannot increase cardiac output and prevent syncope. It is possible that the time to syncope may be delayed after injection of atropine. In addition, the timing of atropine injection may be critical; once presyncope begins, it is probably too late to stop it.

Cardiac pacing has been used to prevent bradycardia and syncope, but previous pacing trials have yielded conflicting results probably due to the vasodepressor component. One recent study showed that patients with unexplained syncope associated with abrupt bradycardia displayed a better response to pacing therapy than those with gradual onset bradycardia (Sud et al. 2007). Different selection criteria in patients who are candidates for cardiac pacing, for example, presence, absence or severity of the cardioinhibitory reflex, may separate positive from negative trials (Brignole & Sutton, 2007).

Sympathetic vasoconstriction in presyncope

Previous investigations have demonstrated that a sudden withdrawal of sympathetic activity leads to vasodilatation, causing hypotension and neurally mediated syncope (Wallin & Sundlof, 1982; Morillo et al. 1997; Jardine et al. 1998; Kamiya et al. 2005). However, two case reports showed that vasomotor sympathetic withdrawal may occur late, after the onset of hypotension (Wallin & Sundlof, 1982; Jardine et al. 1996). Indeed, we found that MSNA decreased rapidly 20 s prior to presyncope. This observation is consistent with the recent findings of Cooke et al. (2009) and Vaddadi et al. (2010), and suggest that withdrawal of sympathetic activity may not always be a prerequisite for syncope. Certainly, we recognize that MSNA recordings are inherently limited to the skeletal muscle vasculature. Whether sympathetic withdrawal in other vascular bed(s) follows the same pattern prior to and during (pre)syncope needs to be determined.

In our study, MSNA burst frequency and total activity during presyncope did not differ between those who had decreases in both cardiac output and total peripheral resistance (group A) and those who had the decrease in cardiac output only (group B). Interestingly, burst incidence decreased rapidly at presyncope in group A but remained unchanged in group B. These observations suggest that the decreases of burst frequency and total activity in group B may be attributable to a decrease of heart rate rather than burst incidence. It is possible that the two ways of changing burst frequency or total activity may lead to different changes of the number of vasoconstrictor impulses, release of noradrenaline and the degree of vasoconstriction (Wallin & Charkoudian, 2007). However, plasma noradrenaline (279 ± 34 vs. 246 ± 58 pg ml−1, P= 0.37) and adrenaline concentrations (79 ± 22 vs. 50 ± 13 pg ml−1, P= 0.68) were not different between groups A and B at presyncope, indicating that the release of noradrenaline from sympathetic nerve terminals may be similar between groups. Presyncopal subjects in group B had no change in total peripheral resistance despite a decrease in MSNA prior to presyncope. This suggests that their vascular tone was dependent on other circulating vasoactive substances or vasoconstriction occurred in other vascular beds or they had enhanced venoarteriolar response (a local axonal reflex, which causes non-baroreflex, non-adrenergically mediated regional vasoconstriction, and is believed to contribute to ∼45% of the increase in systemic vascular resistance during orthostasis) (Henriksen et al. 1973; Henriksen, 1991; Okazaki et al. 2005).

In the majority of the presyncopal subjects, the decrease of total peripheral resistance occurred earlier than the obvious decrease of MSNA (i.e. 40 vs. 20 s prior to presyncope). Several possibilities may account for this observation. First, vasodilatation in other vascular beds, such as splanchnic and renal circulations could occur early in the development of (pre)syncope. Second, the coupling between sympathetic activity and vasoconstriction may be altered some minutes before syncope. For example, MSNA bursts were found to fuse in some subjects a few minutes before presyncope (Cooke et al. 2009), and burst properties changed progressively to those similar to skin sympathetic nerve activity during syncope (Iwase et al. 2002). Low-frequency oscillation of MSNA variability was found to decrease during development of syncope, preceding sympathetic withdrawal, bradycardia and severe hypotension (Kamiya et al. 2005). All these results seem to support the notion that the transduction of sympathetic outflow to vascular resistance may be altered before sympathetic withdrawal actually occurs. Additionally, there may be a mismatch between nerve firing and noradrenaline release, though this is most noticeable in patients with a clinical history of syncope (Vaddadi et al. 2011). Third, active vasodilatation (predominantly β2 mediated) and/or humorally mediated vasodilatation may contribute to the early decrease in total peripheral resistance. It has been proposed that circulating adrenaline alone without any changes in sympathetic activity may also contribute to the dilation during syncope by stimulating vasodilating β2-adrenergic receptors in skeletal muscle blood vessels. This notion seems to be supported by the results of Goldstein et al. (2003), showing that syncopal patients had excessive increases in adrenaline preceding syncope. It was previously found that the profound vasodilatation in the forearm during true syncope (loss of consciousness) was not mediated solely by sympathetic withdrawal, and humoral-mediated vasodilatation may be involved as well (Dietz et al. 1997).

Study limitations

First, beat-to-beat haemodynamics were derived from the Modelflow method. Although this method has been validated in different populations (Leonetti et al. 2004; Bogert & van Lieshout, 2005; Reisner et al. 2007) and has been compared with the beat-to-beat Doppler ultrasound technique (Sugawara et al. 2003; van Lieshout et al. 2003), the absolute values obtained have never been shown to be the same as those from ‘gold-standard’ invasive methods. Nevertheless, it has been reported that the Modelflow method tracks fast changes in haemodynamics during various experimental protocols, including orthostasis and exercise (Sugawara et al. 2003; van Lieshout et al. 2003). In our study, tracking of changes rather than identifying the absolute values are more important. Second, none of our subjects had a history of recurrent syncope, and these subjects may be different from clinical patients with recurrent syncope. Thus, our findings and conclusions are restricted to healthy individuals with isolated situational orthostatic syncope only. Third, upright tilt was terminated at presyncope but not syncope. It is possible that sympathetic and haemodynamic responses are different at true syncope compared with at presyncope. Fourth, subjects in group B were all females. Whether the unique responses (i.e. marked decreases in cardiac output with no changes in total peripheral resistance) at presyncope can also be seen in males need to be investigated. Fifth, we did not repeat the tilt test in presyncopal subjects and, therefore, we do not know the reproducibility of the responses.

In summary, MSNA and haemodynamic responses, and sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity during early tilting (symptom-free stage) were not different between presyncopal and non-presyncopal subjects. Systemic hypotension during neurally mediated syncope was mediated by a drop in cardiac output in all subjects, accompanied by a progressive decrease in total peripheral resistance in the majority (64% of the presyncopal subjects). In a smaller subset (36%), total peripheral resistance was well maintained even at presyncope. Thus, a moderate fall in cardiac output with coincident vasodilatation or a marked fall in cardiac output with no changes in peripheral vascular resistance contributes to syncope. However, an intrinsic impairment of sympathetic baroreflex function and/or vasomotor responsiveness is not the cause of neurally mediated syncope in these subjects.

Acknowledgments

The time and effort put forth by the subjects is greatly appreciated. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL075283 and HL088184) and the Clinical and Translational Research Center (formerly, the General Clinical Research Center) grant (RR00633).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BP

blood pressure

- MSNA

muscle sympathetic nerve activity

Author contributions

Q.F. contributed to (1) conception and design of the experiments; (2) collection, analysis and interpretation of data; and (3) drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. B.V. contributed to (1) analysis and interpretation of data; and (2) drafting the article. W.W. contributed to interpretation of data. B.D.L. contributed to (1) conception and design of the experiments; and (2) interpretation of data. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Barcroft H, Edholm OG, McMichael J, Sharpey-Shafer EP. Posthaemorrhagic fainting study by cardiac output and forearm flow. Lancet. 1944;i:489–491. [Google Scholar]

- Bogert LW, van Lieshout JJ. Non-invasive pulsatile arterial pressure and stroke volume changes from the human finger. Exp Physiol. 2005;90:437–446. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.030262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignole M, Sutton R. Pacing for neurally mediated syncope: is placebo powerless? Europace. 2007;9:31–33. doi: 10.1093/europace/eul169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke WH, Rickards CA, Ryan KL, Kuusela TA, Convertino VA. Muscle sympathetic nerve activity during intense lower body negative pressure to presyncope in humans. J Physiol. 2009;587:4987–4999. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.177352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Wilson TE, Shibasaki M, Hodges NA, Crandall CG. Baroreflex modulation of muscle sympathetic nerve activity during posthandgrip muscle ischemia in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1679–1686. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz NM, Halliwill JR, Spielmann JM, Lawler LA, Papouchado BG, Eickhoff TJ, Joyner MJ. Sympathetic withdrawal and forearm vasodilation during vasovagal syncope in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:1785–1793. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.6.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein SE, Stampfer M, Beiser GD. Role of the capacitance and resistance vessels in vasovagal syncope. Circulation. 1968;37:524–533. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.37.4.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Arbab-Zadeh A, Perhonen MA, Zhang R, Zuckerman JH, Levine BD. Hemodynamics of orthostatic intolerance: implications for gender differences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H449–H457. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00735.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Okazaki K, Shibata S, Shook RP, VanGunday TB, Galbreath MM, Reelick MF, Levine BD. Menstrual cycle effects on sympathetic neural responses to upright tilt. J Physiol. 2009;587:2019–2031. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.168468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Shook RP, Okazaki K, Hastings JL, Shibata S, Conner CL, Palmer MD, Levine BD. Vasomotor sympathetic neural control is maintained during sustained upright posture in humans. J Physiol. 2006;577:679–687. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Witkowski S, Okazaki K, Levine BD. Effects of gender and hypovolemia on sympathetic neural responses to orthostatic stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R109–R116. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00013.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzeboom KS, Mairuhu G, Reitsma JB, Linzer M, Wieling W, van Dijk N. Lifetime cumulative incidence of syncope in the general population: a study of 549 Dutch subjects aged 35–60 years. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:1172–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisolf J, Westerhof BE, van Dijk N, Wesseling KH, Wieling W, Karemaker JM. Sublingual nitroglycerin used in routine tilt testing provokes a cardiac output-mediated vasovagal response. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Frank SM, Naqibuddin M, Dendi R, Snader S, Calkins H. Sympathoadrenal imbalance before neurocardiogenic syncope. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:53–58. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02997-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwill JR. Segregated signal averaging of sympathetic baroreflex responses in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:767–773. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.2.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen O. Sympathetic reflex control of blood flow in human peripheral tissues. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1991;603:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen O, Nielsen SL, Paaske WP, Sejrsen P. Autoregulation of blood flow in human cutaneous tissue. Acta Physiol Scand. 1973;89:538–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1973.tb05547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch AT, Levenson DJ, Cutler SS, Dzau VJ, Creager MA. Regional vascular responses to prolonged lower body negative pressure in normal subjects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1989;257:H219–H225. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.1.H219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase S, Mano T, Kamiya A, Niimi Y, Fu Q, Suzumura A. Syncopal attack alters the burst properties of muscle sympathetic nerve activity in humans. Auton Neurosci. 2002;95:141–145. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(01)00362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardine DL, Ikram H, Crozier IG. Autonomic control of asystolic vasovagal syncope. Heart. 1996;75:528–530. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.5.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardine DL, Ikram H, Frampton CM, Frethey R, Bennett SI, Crozier IG. Autonomic control of vasovagal syncope. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;274:H2110–H2115. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.6.H2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardine DL, Melton IC, Crozier IG, English S, Bennett SI, Frampton CM, Ikram H. Decrease in cardiac output and muscle sympathetic activity during vasovagal syncope. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1804–H1809. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00640.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellema WT, Wesseling KH, Groeneveld AB, Stoutenbeek CP, Thijs LG, van Lieshout JJ. Continuous cardiac output in septic shock by simulating a model of the aortic input impedance: a comparison with bolus injection thermodilution. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1317–1328. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199905000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A, Hayano J, Kawada T, Michikami D, Yamamoto K, Ariumi H, Shimizu S, Uemura K, Miyamoto T, Aiba T, Sunagawa K, Sugimachi M. Low-frequency oscillation of sympathetic nerve activity decreases during development of tilt-induced syncope preceding sympathetic withdrawal and bradycardia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1758–H1769. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01027.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienbaum P, Karlssonn T, Sverrisdottir YB, Elam M, Wallin BG. Two sites for modulation of human sympathetic activity by arterial baroreceptors? J Physiol. 2001;531:861–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0861h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti P, Audat F, Girard A, Laude D, Lefrere F, Elghozi JL. Stroke volume monitored by modeling flow from finger arterial pressure waves mirrors blood volume withdrawn by phlebotomy. Clin Auton Res. 2004;14:176–181. doi: 10.1007/s10286-004-0191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T. Vasovagal syncope and the carotid sinus mechanism. BMJ. 1932;12:873–874. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.3723.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morillo CA, Eckberg DL, Ellenbogen KA, Beightol LA, Hoag JB, Tahvanainen KU, Kuusela TA, Diedrich AM. Vagal and sympathetic mechanisms in patients with orthostatic vasovagal syncope. Circulation. 1997;96:2509–2513. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosqueda-Garcia R, Furlan R, Fernandez-Violante R, Desai T, Snell M, Jarai Z, Ananthram V, Robertson RM, Robertson D. Sympathetic and baroreceptor reflex function in neurally mediated syncope evoked by tilt. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2736–2744. doi: 10.1172/JCI119463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RH, Thompson LJ, Bowers JA, Albright CD. Hemodynamic effects of graded hypovolemia and vasodepressor syncope induced by lower body negative pressure. Am Heart J. 1968;76:799–811. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(68)90266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki K, Fu Q, Martini ER, Shook R, Conner C, Zhang R, Crandall CG, Levine BD. Vasoconstriction during venous congestion: effects of venoarteriolar response, myogenic reflexes, and hemodynamics of changing perfusion pressure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1354–R1359. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00804.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner A, Xu D, Ryan K, Convertino V, Mukkamala R. Comparison of cardiac output monitoring methods for detecting central hypovolemia due to lower body negative pressure. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2007;2007:955–958. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2007.4352450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D. The epidemic of orthostatic tachycardia and orthostatic intolerance. Am J Med Sci. 1999;317:75–77. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199902000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serletis A, Rose S, Sheldon AG, Sheldon RS. Vasovagal syncope in medical students and their first-degree relatives. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1965–1970. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sud S, Klein GJ, Skanes AC, Gula LJ, Yee R, Krahn AD. Implications of mechanism of bradycardia on response to pacing in patients with unexplained syncope. Europace. 2007;9:312–318. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara J, Tanabe T, Miyachi M, Yamamoto K, Takahashi K, Iemitsu M, Otsuki T, Homma S, Maeda S, Ajisaka R, Matsuda M. Non-invasive assessment of cardiac output during exercise in healthy young humans: comparison between Modelflow method and Doppler echocardiography method. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;179:361–366. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-6772.2003.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triebwasser JH, Johnson RL, Burpo RP, Campbell JC, Reardon WC, Blomqvist CG. Noninvasive determination of cardiac output by a modified acetylene rebreathing procedure utilizing mass spectrometer measurements. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1977;48:203–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaddadi G, Esler MD, Dawood T, Lambert E. Persistence of muscle sympathetic nerve activity during vasovagal syncope. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2027–2033. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaddadi G, Guo L, Esler M, Socratous F, Schlaich M, Chopra R, Eikelis N, Lambert G, Trauer T, Lambert E. Recurrent postural vasovagal syncope: sympathetic nervous system phenotypes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:711–718. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.962332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallbo AB, Hagbarth KE, Torebjork HE, Wallin BG. Somatosensory, proprioceptive, and sympathetic activity in human peripheral nerves. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:919–957. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.4.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lieshout JJ, Toska K, van Lieshout EJ, Eriksen M, Walloe L, Wesseling KH. Beat-to-beat noninvasive stroke volume from arterial pressure and Doppler ultrasound. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;90:131–137. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-0901-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheyden B, Gisolf J, Beckers F, Karemaker JM, Wesseling KH, Aubert AE, Wieling W. Impact of age on the vasovagal response provoked by sublingual nitroglycerine in routine tilt testing. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;113:329–337. doi: 10.1042/CS20070042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheyden B, Liu J, van Dijk N, Westerhof BE, Reybrouck T, Aubert AE, Wieling W. Steep fall in cardiac output is main determinant of hypotension during drug-free and nitroglycerine-induced orthostatic vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1695–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin BG, Charkoudian N. Sympathetic neural control of integrated cardiovascular function: insights from measurement of human sympathetic nerve activity. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:595–614. doi: 10.1002/mus.20831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin BG, Delius W, Sundlof G. Human muscle nerve sympathetic activity in cardiac arrhythmias. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1974;34:293–300. doi: 10.3109/00365517409049883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin BG, Sundlof G. Sympathetic outflow to muscles during vasovagal syncope. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1982;6:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(82)90001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissler AM, Warren JV, Estes EH, Jr, McIntosh HD, Leonard JJ. Vasodepressor syncope; factors influencing cardiac output. Circulation. 1957;15:875–882. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.15.6.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]