Abstract

Healthy, but sedentary ageing leads to marked atrophy and stiffening of the heart, with substantially reduced cardiac compliance; but the time course of when this process occurs during normal ageing is unknown. Seventy healthy sedentary subjects (39 female; 21–77 years) were recruited from the Dallas Heart Study, a population-based, random community sample and enriched by a second random sample from employees of Texas Health Resources. Subjects were highly screened for co-morbidities and stratified into four groups according to age: G21−34: 21–34 years, G35−49: 35–49 years, G50−64: 50–64 years, G≥65: ≥65 years. All subjects underwent invasive haemodynamic measurements with right heart catheterization to define Starling and left ventricular (LV) pressure–volume curves. LV end-diastolic volumes (EDV) were measured by echocardiography at baseline, −15 and −30 mmHg lower-body negative pressure, and 15 and 30 ml kg−1 saline infusion with simultaneous measurements of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure. There were no differences in heart rate or blood pressures among the four groups at baseline. Baseline EDV index was smaller in G≥65 than other groups. LV diastolic pressure–volume curves confirmed a substantially greater LV compliance in G21−34 compared with G50−64 and G≥65, resulting in greater LV volume changes with preload manipulations. Although LV chamber compliance in G50−64 and G≥65 appeared identical, pressure–volume curves were shifted leftward, toward a decreased distensibility, with increasing age. These results suggest that LV stiffening in healthy ageing occurs during the transition between youth and middle-age and becomes manifest between the ages of 50 to 64. Thereafter, this LV stiffening is followed by LV volume contraction and remodelling after the age of 65.

Key points

Healthy sedentary ageing leads to stiffening of the heart; however, when this process occurs during ageing has been unknown.

In this study, 70 healthy sedentary subjects were stratified into four groups: ‘young’– G21−34: 21–34 years; ‘early middle-age’– G35−49: 35–49 years; ‘late middle-age’– G50−64: 50–64 years; and ‘seniors’– G≥65: ≥65 years.

Invasive catheter measurements showed a substantially greater left ventricular (LV) compliance (more flexible/less stiff) in G21−34 than G50−64 and G≥65.

Although LV chamber compliance in G50−64 and G≥65 appeared identical, pressure–volume curves were shifted leftward, exhibiting a smaller volume for any given pressure with increasing age.

Our results suggest that LV stiffening with ageing occurs during the transition between youth and middle-age and becomes manifest between the ages of 50–64; LV volume contraction and remodelling follow in the senior years. Early–late middle age thus may represent a ‘sweet spot’ when interventions to prevent stiff ageing hearts may be most effective.

Introduction

Healthy but sedentary ageing leads to marked arterial and cardiac stiffening (Redfield et al. 2005), which are responsible in part for cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation and chronic heart failure (Lakatta, 2003). LV systolic function seems to be relatively preserved during healthy ageing. On the other hand, collagen accumulation and cross-linking of collagen in the extracellular matrix, myocyte loss with slight increases in the size of residual myocytes, and alterations in LV chamber geometry have been observed (de Souza, 2002), which could result in impairments of LV diastolic function (a decrease in cardiac compliance and/or prolonged LV relaxation) (Hirota, 1980; Arbab-Zadeh et al. 2004; Redfield et al. 2005).

Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that healthy but sedentary ageing leads to cardiac atrophy and a prominent increase in LV stiffness assessed by invasive pressure–volume curves (Arbab-Zadeh et al. 2004). This age-associated increase in cardiac stiffness, especially in women, may provide the substrate for heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a disease often observed in the elderly with increased cardiac stiffness (Prasad et al. 2010).

There are only a few strategies that have been shown to have favourable effects on age-related cardiac stiffening in healthy humans. For example, life-long exercise training in Masters athletes completely prevents age-associated cardiac stiffening (Arbab-Zadeh et al. 2004). However, 1 year of vigorous exercise training started after the age of 65 seemed to be insufficient to reverse this cardiac stiffening (Fujimoto et al. 2010). It is unclear at what age cardiac stiffening and remodelling occur during the healthy ageing process. This knowledge would be essential to develop life-long strategies that might forestall age-associated cardiovascular diseases such as HFpEF. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to perform a comprehensive and detailed measurement of haemodynamics and LV structure and function in healthy sedentary individuals across the life span.

Methods

Subject population

Seventy healthy adults (aged 21–77 years; 39 females) were recruited from the Dallas Heart Study, a population-based probability sample of 6101 individuals in the Dallas community who have been carefully screened for cardiovascular disease (Victor et al. 2004). The final cohort was enriched by a second random sample of all employees of Texas Health Resources, a health care entity that is the third largest employer in the DFW metroplex with more than 25,000 employees. Subjects were prospectively recruited and divided into four groups according to their age: G21−34 (21 to 34 years); G35−49 (35 to 49 years); G50−64 (50 to 64 years); and G≥65 (≥65 years). Subjects in G21−34 were considered as ‘young’ and those in G≥65 as ‘seniors’ or ‘older adults’. The period between ‘young’ and ‘seniors’, which is generally considered as middle-age, was subdivided into ‘early middle-age’ (35 to 49 years) and ‘late middle-age’ (50 to 64 years). Sedentary subjects were excluded if they were exercising for ≥30 min 3 times a week. All subjects were rigorously screened for comorbidities including obesity, lung disease, hypertension, LV wall thickness ≥12 mm, coronary artery disease or structural heart disease with baseline and post-exercise transthoracic echocardiograms. Lean body mass was measured by underwater weighing (Roche AF et al. 1996). All subjects signed an informed consent form, which was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas and Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas. All procedures conformed to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Exercise testing

All the subjects performed maximal exercise testing to measure maximal oxygen uptake ( ) as previously reported (Arbab-Zadeh et al. 2004; Fujimoto et al. 2010). A modified Astrand–Saltin incremental treadmill protocol was used to determine peak exercise capacity. Measures of ventilatory gas exchange were made by use of the Douglas bag technique. Gas fractions were analysed by mass spectrometry (Marquette MGA 1100) and ventilatory volumes were measured with a Tissot spirometer. In the present study, maximal heart rate was 104 ± 7% of the predicted maximal heart rate, and we consistently elicited gas exchange variables such as respiratory exchange ratio >1.10, or a ventilatory equivalent for oxygen >35 on virtually all tests.

) as previously reported (Arbab-Zadeh et al. 2004; Fujimoto et al. 2010). A modified Astrand–Saltin incremental treadmill protocol was used to determine peak exercise capacity. Measures of ventilatory gas exchange were made by use of the Douglas bag technique. Gas fractions were analysed by mass spectrometry (Marquette MGA 1100) and ventilatory volumes were measured with a Tissot spirometer. In the present study, maximal heart rate was 104 ± 7% of the predicted maximal heart rate, and we consistently elicited gas exchange variables such as respiratory exchange ratio >1.10, or a ventilatory equivalent for oxygen >35 on virtually all tests.

Experimental protocol

A 6Fr Swan-Ganz catheter was placed from a peripheral antecubital vein under fluoroscopic guidance to measure pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) and right atrial pressure. Correct position of the Swan-Ganz catheter was confirmed by fluoroscopy and by the presence of characteristic pressure waveforms. After the baseline measurements, lower-body negative pressure (LBNP) was used to decrease cardiac filling as we have published previously (Arbab-Zadeh et al. 2004; Fujimoto et al. 2010). Measurements of heart rate, PCWP, LV end-diastolic volume (EDV) and cardiac output were performed after 5 min each of −15 and −30 mmHg LBNP. After at least a 20 min break, repeat measurements were used to confirm a return to a steady state. Cardiac filling was then increased by rapid infusion (100–200 ml min−1) of warm isotonic saline. Measurements were repeated after 15 and 30 ml kg−1 of saline infusion. Cardiac output, and therefore stroke volume, was measured by a modification of the acetylene rebreathing method, with acetylene as the soluble gas and helium as the insoluble gas (Laszlo, 2004; Fujimoto et al. 2010). Total arterial compliance was determined by the ratio of stroke volume and pulse pressure (Chemla et al. 1998). Effective arterial elastance was defined as brachial systolic pressure × 0.9 divided by stroke volume (Kelly et al. 1992; Chen et al. 2001).

Assessment of LV morphology

Cardiac MRI images were obtained using a 1.5 tesla Philips NT scanner to evaluate LV mass, volume and LV mass–volume ratio (Hundley et al. 1995). LVEDV and mass were measured using a steady-state free precision imaging sequence (Katz et al. 1988; Fujimoto et al. 2010).

During cardiac catheterization, LV images were obtained at all levels of LV filling by two-dimensional echocardiography. LV volumes were determined from the apical 4-chamber view by a modified Simpson's method of disks that was used in our previous studies (Arbab-Zadeh et al. 2004; Fujimoto et al. 2010; Prasad et al. 2010). As LV volumes by two-dimensional echocardiography have been reported to underestimate those by gold standard MRI due to image positioning, geometric assumptions and boundary tracing errors (Chukwu et al. 2008), a correction factor was determined as the ratio of LVEDV by echocardiography at baseline to that by cardiac MRI in each subject. By use of this individual correction factor for LVEDV, LVEDV by echocardiography during unloading/loading was corrected and used to construct LV pressure–volume curves.

Assessment of cardiac catheterization data

To evaluate chamber stiffness properties, LV pressure–volume curves were constructed by relating LVEDV and PCWP. For the purposes of the present study, we characterized and here define explicitly two different but related mechanical properties of the heart during diastole: (1) Overall chamber stiffness (or its inverse, compliance) refers to the stiffness constant ‘a’ of the exponential equation describing the pressure–volume curve (see below); and (2) distensibility is used to mean the absolute LVEDV at a given PCWP, independent of stiffness constant ‘a’ (Perhonen et al. 2001; Prasad et al. 2010).

To characterize LV pressure–volume curves, we modelled the data according to an exponential equation (Mirsky, 1984): P = P∞ (expa(V−V0)− 1), where P is PCWP, P∞ is pressure asymptote of the curve (this variable has no intrinsic physiological significance but is the modelling parameter which describes LV pressure when LVEDV index becomes −∞ in this model), V is LVEDV index and V0 is equilibrium volume or the volume at which P= 0 mmHg pressure as previously reported. Overall LV chamber stiffness was assessed from the LV stiffness constant ‘a’ that describes the shape of the curve. As external constraints influence LV volumes and pressures (Dauterman et al. 1995), LV end-diastolic transmural filling pressure was calculated as PCWP – right atrial pressure (Belenkie et al. 2002) and used to construct transmural pressure–volume (LVEDV index/LV transmural pressure) curves (Arbab-Zadeh et al. 2004; Fujimoto et al. 2010; Prasad et al. 2010).

The PCWP and stroke volume data were used to construct Starling (stroke volume index/PCWP) curves. The LVEDV, stroke volume and mean arterial pressure were used to construct preload–recruitable stroke work relationships. The slopes of the LVEDV–stroke work relationship were used to assess global LV systolic function (Glower et al. 1985).

Assessment of overall cardiovascular function

The primary outcome variables in the present study included: (a) LV compliance assessed from the slopes of the pressure–volume curves, which reflects LV static diastolic function; (b) LV distensibility assessed from LV end-diastolic volumes at any given LV filling pressure; and (c) global LV performance as assessed from Starling curves and preload-recruitable stroke work. Secondary variables included: (a) arterial function as assessed by total aortic compliance and arterial elastance; and (b) functional responses during exercise as assessed by  .

.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using commercially available software. Data were expressed as mean ± SD in tables and mean ± SEM in figures. Continuous data were analysed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis, and the Mann–Whitney rank sum test was used for non-normally distributed data. Categorical data were assessed by chi-square test. For data obtained during cardiac catheterization, a two-way repeated ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analysis was applied to evaluate the differences between groups. For pressure–volume curves, a multivariate regression analysis was conducted on the repeated measures data, modelling pressure by use of the covariates volume and subject group. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Subject characteristics

As shown in Table 1, there were no differences in gender, height, body weight, lean body mass, heart rate or 24 h systolic and diastolic blood pressures among the four groups.

Table 1.

Subjects' characteristics

| G21–34 (21–34 years) | G35–49 (35–49 years) | G50–64 (50–64 years) | G≥65 (≥65 years) | ANOVA P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 14 | 19 | 23 | 14 | |

| Female (%) | 35 | 68 | 57 | 64 | 0.32 |

| Age (years) | 28 ± 4 | 42 ± 4* | 57 ± 4*† | 69 ± 3*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 171 ± 8 | 168 ± 9 | 171 ± 10 | 166 ± 11 | 0.43 |

| Body weight (kg) | 70 ± 9 | 68 ± 14 | 77 ± 14 | 72 ± 13 | 0.15 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.82 ± 0.16 | 1.77 ± 0.22 | 1.90 ± 0.21 | 1.82 ± 0.18 | 0.21 |

| Lean body mass (kg) | 51 ± 9 | 47 ± 9 | 50 ± 12 | 50 ± 8 | 0.61 |

| Heart rate (beat min−1) | 75 ± 8 | 72 ± 10 | 73 ± 8 | 75 ± 5 | 0.73 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 125 ± 10 | 119 ± 9 | 122 ± 10 | 122 ± 10 | 0.39 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 72 ± 3 | 71 ± 6 | 72 ± 6 | 73 ± 7 | 0.81 |

(ml kg−1 min−1) (ml kg−1 min−1) |

31.2 ± 7.1 | 27.7 ± 5.4 | 26.0 ± 4.5* | 21.1 ± 4.0*†‡ | < 0.001 |

Values are mean ± SD. BP, blood pressure

, maximal oxygen uptake at exercise test. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were obtained from 24 h BP monitoring.

, maximal oxygen uptake at exercise test. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were obtained from 24 h BP monitoring.

P < 0.05 vs. G21−34

P < 0.05 vs. G35−49

P < 0.05 vs. G50−64.

Cardiac size and vascular function

As shown in Table 2, LVEDV index by MRI was negatively correlated with ageing. There were no differences in LVEDV index among G21−34, G35−49 and G50−64, while LVEDV index in G≥65 was significantly smaller than those in other younger age groups (P≤ 0.003). There was a trend for a smaller LV mass index along with ageing, which was statistically less convincing (P= 0.15). Total arterial compliance was negatively correlated with ageing, and was lowest in those ≥65 years.

Table 2.

Baseline ventricular–vascular function

| G21–34 (n= 14) | G35–49 (n= 19) | G50–64 (n= 23) | G≥65 (n= 14) | ANOVA P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventricular function | |||||

| PCWP (mmHg) | 12.7 ± 1.3 | 11.9 ± 2.6 | 11.9 ± 2.4 | 11.1 ± 1.5 | 0.30 |

| LVEDV index (ml m−2) | 66.1 ± 7.4 | 60.2 ± 7.1 | 59.5 ± 9.4 | 49.9 ± 6.1*†‡ | <0.001 |

| LVESV index (ml m−2) | 23.1 ± 4.3 | 20.1 ± 5.3 | 16.9 ± 5.0* | 14.1 ± 3.0*† | <0.001 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 65 ± 6 | 67 ± 7 | 72 ± 6 | 72 ± 4 | 0.002 |

| LV mass index (g m−2) | 54.7 ± 7.5 | 54.2 ± 13.3 | 49.9 ± 8.0 | 47.9 ± 6.6 | 0.15 |

| LV mass–volume ratio (g ml−1) | 1.22 ± 0.16 | 1.18 ± 0.27 | 1.20 ± 0.17 | 1.07 ± 0.20 | 0.25 |

| Cardiac output (reb) (l min−1) | 6.2 ± 1.5 | 4.5 ± 0.9* | 4.9 ± 0.7* | 4.8 ± 0.8* | <0.001 |

| Cardiac index (reb) (l min−1 m−2) | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.5* | 2.6 ± 0.4* | 2.6 ± 0.3* | <0.001 |

| Stroke volume index (reb) (ml m−2) | 45.0 ± 7.8 | 38.1 ± 6.2* | 41.2 ± 7.1 | 36.8 ± 6.9*‡ | <0.001 |

| Grouped LV stiffness constant | 0.045 | 0.052 | 0.083 | 0.072 | |

| Grouped LV equilibrium volume (ml) | 28.8 | 31.1 | 21.0 | 13.3 | |

| Grouped pressure asymptote (mmHg) | 2.8 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | |

| LV stiffness constant | 0.038 ± 0.021 | 0.053 ± 0.025 | 0.067 ± 0.033* | 0.068 ± 0.034* | 0.02 |

| LV equilibrium volume (ml) | 27.4 ± 12.7 | 31.9 ± 12.5 | 29.6 ± 14.7 | 17.9 ± 10.5 †‡ | 0.03 |

| Pressure asymptote (mmHg) | 8.4 ± 12.5 | 8.0 ± 9.9 | 4.7 ± 5.3 | 3.1 ± 3.2 | 0.22 |

| Vascular function | |||||

| Total arterial compliance (ml mmHg−1) | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 6 | 1.2 ± 0.3*†‡ | <0.001 |

| Arterial elastance (mmHg ml−1) | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.4*†‡ | <0.001 |

Left ventricular (LV) volumes and mass obtained by cardiac MRI. PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; (reb), by acetylene rebreathing technique; EDV, end-diastolic volume; EDV, end-systolic volume.

P < 0.05 vs. G21−34

P < 0.05 vs. G35−49

P < 0.05 vs. G50−64.

Catheterization data

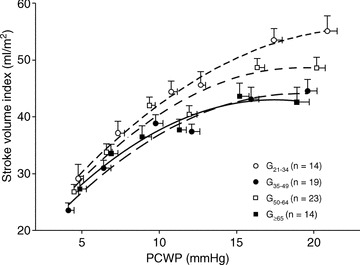

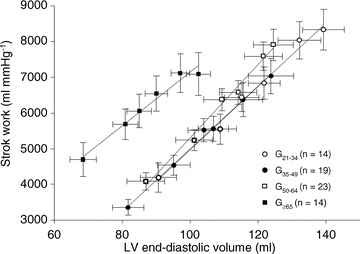

Stroke volume index in G21−34 was larger than those in G35−49, G50−64 and G≥65 at baseline (P= 0.001, P= 0.11 and P < 0.001) and during saline infusion (P < 0.001, P= 0.06 and P < 0.001), resulting in a substantial upward shift of the Starling curve in G21−34 compared to the other three groups (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 2, the LVEDV–stroke work relationship in G≥65 was shifted leftward because of the smaller LVEDV at any given stroke work with no change in its slope. The slope of the relationships were 88.1 mmHg in G21−34, 89.1 mmHg in G35−49, 102.9 mmHg in G50−64 and 75.7 mmHg in G≥65. When analysed individually, there were no differences in the slope of the LVEDV–stroke work relationships among the four groups (79.5 ± 18.9 mmHg in G21−34, 84.3 ± 33.5 mmHg in G35−49, 108.7 ± 43.1 mmHg in G50−64 and 89.4 ± 51.2 mmHg in G≥65, P= 0.10).

Figure 1. Frank–Starling relationship.

Global ventricular performance for sedentary subjects in different age groups. Lines represent second linear regressions for G21−34 (21–34 years) (r2= 0.99), G35−49 (35–49 years) (r2= 0.96), G50−64 (50–64 years) (r2= 0.95) and G≥65 (≥65 years) (r2= 0.97). Note the largest stroke volume index for any pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) and substantially upward shifted Starling curve in G21−34.

Figure 2. Preload recruitable stroke work.

Lines represent linear regressions for G21−34 (21–34 years) (r2= 0.99), G35−49 (35–49 years) (r2= 0.99), G50−64 (50–64 years) (r2= 0.99) and G≥65 (≥65 years) (r2= 0.97). No differences were noted in the slope of preload-stroke work relationships among the 4 groups.

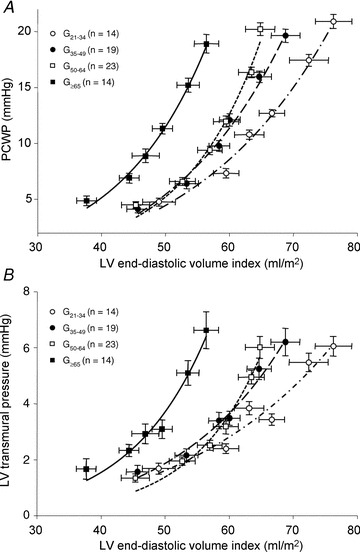

LV pressure–volume curves

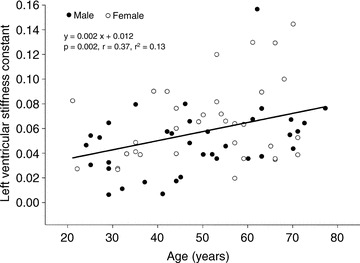

The results of LV pressure–volume curves are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 3A. The LV pressure–volume curve in G≥65 was steeper and shifted leftward compared to that of G21−34, suggesting a stiffer and less distensible LV in G≥65 compared to G21−34, as reported previously (Arbab-Zadeh et al. 2004). Although LV chamber compliance in G50−64 and G≥65 are similar, the LV pressure–volume curve was shifted leftward, suggesting a reduced LV distensibility and LV volume contraction after the age of 65 (Fig. 3A). When analysed individually and statistically, LV stiffness constant ‘a’ in G50−64 (0.067 ± 0.033, P= 0.026) and G≥65 (0.068 ± 0.034, P= 0.042) were larger than that in G21−34 (0.038 ± 0.021), while no statistical difference was observed in LV stiffness constant between G21−34 and G35−49 (0.038 ± 0.021 vs. 0.053 ± 0.025, P= 0.47). When absolute age was used instead of pre-specified age groups, there was a positive correlation between LV stiffness constant and age (P= 0.002), Fig. 4.

Figure 3. Diastolic pressure–volume relationships.

A, pressure–volume curves for G21−34 (21–34 years) (r2= 0.99), G35−49 (35–49 years) (r2= 0.99), G50−64 (50–64 years) (r2= 0.98) and G≥65 (≥65 years) (r2= 0.99). Note the steeper slope of pressure–volume curve for G50−64 and G≥65 compared to G21−34, suggesting a stiffer ventricle. Although the LV chamber compliance in G50−64 and G≥65 appeared to be identical, LV pressure–volume curves shifted leftward with increasing age. B, transmural pressure–volume curves for G21−34 (r2= 0.95), G35−49 (r2= 0.98), G50−64 (r2= 0.97) and G≥65 (r2= 0.97). Note the steeper slope of the transmural pressure–volume curve for G50−64 and G≥65 compared to G21−34, also suggesting a stiffer ventricle. Note the different scale used for Fig. 3A and B.

Figure 4. Relationship between LV stiffness constant and continuous age.

LV stiffness constant was positively associated with age. •, male and ○, female.

LV transmural pressure–volume curves, which are more specific for LV myocardial compliance with little effects of external constraint, are shown in Fig. 3B. LV transmural pressure–volume curves in G50−64 and G≥65 appeared stiffer than G21−34. Although the slope of the pressure–volume curves in G50−64 and G≥65 were similar, the LV transmural pressure–volume curve in G≥65 was leftward shifted compared to that in G50−64, suggesting a reduced LV distensibility after the age of 65.

As there may be gender differences in LV stiffness, individual LV stiffness constants were analysed by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with Fisher least significant difference as post hoc test with gender as a covariate. After controlling for gender, LV stiffening was also associated with ageing (overall P value = 0.030). LV stiffness constants in G50−64 and G≥65 were larger than that in G21−34 (P= 0.011 and P= 0.017), while no difference was observed in LV stiffness constant between G21−34 and G35−49 or between G35−49 and G50−64. A linear regression analysis with gender as a covariate also showed that LV stiffness constant was positively associated with absolute age (P= 0.002, r= 0.43, r2= 0.18).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time in healthy sedentary humans that age-associated LV stiffening occurs primarily during the transition between youth and middle-age and appears essentially complete by the age of 64. With further ageing beyond 65 years, this LV stiffening is followed by a decreased LV distensibility. While we have previously shown that sedentary ageing resulted in stiffening and remodelling of the heart, which could be completely prevented by life-long exercise training, this study extends these results by demonstrating at which age range the age-associated changes in the LV stiffening and volume occur.

Effects of ageing on LV compliance

The age-dependent alterations in LV compliance could be related to a decrease in the number of myocytes with a concomitant hypertrophic change of the residual myocytes (Lakatta, 2003) and a disproportionate collagen deposition with collagen cross-linking in the interstitium of the LV (de Souza, 2002). These changes within the myocardium and/or LV hypertrophy have been considered to cause age-associated stiffening of the heart (Matsubara et al. 2000). Advanced glycation end-products (AGE), which accumulate slowly on collagen in cardiovascular walls (Kass et al. 2001) and also bind to receptors for AGE (RAGE) and cause inflammation, could contribute to the fibrous burden in the aged hearts.

In addition to the increased LV stiffening up to the age of 64, we observed that the slope of the pressure–volume curves in G35−49 seemed to be of an intermediate phenotype and slightly steeper than those in G21−34, although no statistical difference in individual stiffness constant was observed between these two groups (Fig. 3A). These findings may suggest that LV stiffening occurs during the transition between youth and middle-age in healthy individuals. Our speculation is supported by previous reports on ageing and myocardial fibrosis in humans or animal models. For example, in aged rats, progressive increases in LV fibrosis and subsequent declines of LV compliance were observed, suggesting increased risks for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Sangaralingham et al. 2011). However, there are no reports that evaluated LV fibrosis in healthy human hearts.

In human autopsy specimens, Sasaki et al. (1975) reported a significant correlation (r= 0.72, P < 0.01) between age and the percentage of myocardial fibrosis in the hearts of patients who died from non-cardiac causes (age from 0 to 80 years). Song et al. (1999) evaluated fibrotic changes of the cardiac conduction systems in 230 patients (age from 1 to 91 years) who died of non-cardiovascular diseases. They reported that fibrotic changes in the sino-atrial node, His bundle and left bundle branch were observed only after 40 years of age, and that the percentage of fibrotic changes increased with every 20 years of ageing. Based on these findings and the current study, myocardial fibrosis in healthy ageing seems to occur after the transition between youth and middle-age, which could result in an overt impairment of LV compliance at the age of 50–64.

Effects of ageing on LV morphology

We demonstrated that there was a negative relationship between age and LVEDV index, with the greatest reduction in those ≥65 years of age. Consistent with the present study, Cheng et al. (2009) reported that LVEDV by MRI was negatively related with ageing in subjects with no overt heart disease, and that subjects older than 65 years had smaller LV volumes than those younger than 65 years. LV end-diastolic diameter measured by two-dimensional echocardiography was also shown to be negatively correlated to age in healthy subjects (Cheng et al. 2010). On the other hand, in patients with hypertension, obesity or diabetes mellitus, no age-associated decrease of LV size was observed, due probably to the LV remodelling related to a pressure and/or volume overload stimulus (Cheng et al. 2010). In the present study, we observed the decrease in LVEDV not only at baseline but also at all LV filling pressures in G≥65. LV equilibrium volume was also significantly decreased in G≥65 than the other three groups. These findings indicate a decrease in LV distensibility after the age of 65, which was likely to be due to age-associated structural changes of the heart and may be irreversible once completed (Fujimoto et al. 2010). As no differences were observed in heart rate or global LV systolic function (as discussed below) among the four groups, a decreased resting cardiac output in G≥65 may be partly explained by the impairments in LV compliance and distensibility with ageing.

Effects of ageing on LV systolic function

Previous studies evaluating longitudinal LV systolic function by use of systolic myocardial tissue velocities demonstrated an age-associated decline of longitudinal systolic function (Chahal et al. 2010). On the contrary, circumferential LV systolic function can be preserved or increased with ageing judging from a preserved global peak systolic velocities (Föll et al. 2010), or an increased LV fractional shortening and ejection fraction, although all these variables are load-dependent indexes of LV systolic function.

Global LV systolic function can be evaluated by use of load-independent LV end-systolic elastance (Ees) or the slope of preload-recruitable stroke–work relationships. Redfield et al. (2005) reported by use of a non-invasive estimate of Ees that global LV systolic function increased with ageing in healthy humans, which was coupled with an increase of effective arterial elastance. We observed no age-associated changes in the slope of preload–stroke work relationships. These results may also suggest that global LV systolic function is preserved along with healthy ageing. In the present study, LV stroke work in G≥65 was substantially greater at a given LVEDV than the other three groups with no difference in global LV systolic function as shown in Fig. 2. These findings may suggest that greater work was required for myofilaments of the cardiomyocyte to function as a bidirectional spring affecting diastolic expansion and end-systolic compression.

Effects of ageing on global cardiovascular function

Consistent with previous studies, we observed the highest  in the youngest age group and a gradual decline of

in the youngest age group and a gradual decline of  with ageing. This age-associated decline of

with ageing. This age-associated decline of  was related to an increased arterial elastance and a decreased peripheral oxygen extraction during maximal exercise testing (authors’ unpublished data). A downward shift of the Starling curves especially at higher PCWP in G35−49, G50−64 and G≥65 compared to G21−34 could be partly explained by a greater afterload due to arterial stiffening in G35−49, G50−64 and G≥65 with no changes in global LV systolic function among the four groups.

was related to an increased arterial elastance and a decreased peripheral oxygen extraction during maximal exercise testing (authors’ unpublished data). A downward shift of the Starling curves especially at higher PCWP in G35−49, G50−64 and G≥65 compared to G21−34 could be partly explained by a greater afterload due to arterial stiffening in G35−49, G50−64 and G≥65 with no changes in global LV systolic function among the four groups.

Clinical relevance

We reported that Masters athletes, who had sustained their endurance exercise training >5 days week−1 for an average of 23 ± 8 years, had similar LV compliance to those of sedentary young subjects (Arbab-Zadeh et al. 2004). Most of the Masters athletes started their exercise training at the age of 35–49, which was equivalent to the age range when age-associated LV stiffening seemed to occur in the healthy ageing process. In the present study, we demonstrated that the stiffening of the heart was essentially complete by age 64, while volume contraction and remodelling of the LV myocardium seemed to become most prominent in this age group. We previously reported that 1 year of exercise training in sedentary subjects older than 65 years caused no improvement in LV compliance or distensibility. Judging from these findings, healthy adults may need to start exercise training at least during the transition between youth and middle-age in order for exercise training to prevent myocardial stiffening and age-associated LV remodelling.

We divided subjects into four age groups (G21−34, G35−49, G50−64 and G≥65) because we felt that defining biological differences in cardiovascular structure was particularly relevant for these stages of life, both psychologically and biologically. Binning of age ranges, which is especially common in the ageing research field (McQuillan et al. 2001; Khan et al. 2003; Sui et al. 2007), reduces noise in variables of interest, but decreases temporal resolution for smaller age ranges. Although the use of age as a continuous variable might also be informative of age effects on cardiovascular structure and function, the assumption of linearity throughout age with such an analysis obscures major shifts in socioeconomic and biological status that may hide rather than enlighten relevant differences.

Relative energy imbalance, specifically insufficient energy expenditure relative to caloric intake, has been hypothesized to cause lipotoxicity and stiffening of the aged heart due to the accumulation of abnormal metabolites such as triglycerides and AGE (Prasad & Levine, 2008). Similarly, calorie restriction decreases AGE levels not only by lowering blood glucose but also by reducing the consumption of dietary AGE (Yan et al. 2010), which was shown to improve LV stiffness in middle-age subjects by non-invasive measures (Riordan et al. 2008). However, it is unclear whether modification of the ratio of energy expenditure to caloric intake could improve LV compliance in elderly individuals. Alagebrium, which is an AGE crosslink breaker (Kass et al. 2001), has been shown to improve LV compliance in animals (Asif et al. 2000). In healthy sedentary elderly humans, a phase II trial of an alagebrium adjunct therapy with exercise training is now under way (NIH http://clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01014572). We hypothesize that exercise training started prior to the age of 64 may have the potential to prevent the age-associated LV stiffening. In healthy elderly individuals in whom stable AGE cross-linking of collagen may have been already formed, AGE cross-link breakers might be necessary to reverse age-associated stiffening of the LV. These countermeasures have the potential to reduce the occurrence of cardiovascular diseases such as HFpEF in the future.

Study limitations

There are several limitations. First, the number of subjects, particularly of each gender, was relatively small in each group mainly because of the invasive nature of the instrumentation, preventing a convincing examination of gender differences in this ageing response. Thus, we chose to bin our age groups to maintain statistical power at the expense of age resolution in a strategy that was determined prospectively. We do not mean to imply that there are sudden and dramatic changes as a person advances from age 49 to age 50, for example. Rather, our data emphasize that as groups of men and women advance through the stages of life as they age, that there are real and measureable biological changes that occur in cardiovascular structure. Second, LV pressure–volume curves were evaluated by use of mean PCWP as a surrogate for LV end-diastolic pressure. We performed a rigorous screening for cardiovascular disease and excluded subjects who had valvular abnormalities or pulmonary disease which might alter the relationship between PCWP and LV end-diastolic pressure. Therefore, the advantage of a direct measurement of LV end-diastolic pressure by use of a left heart catheter does not outweigh the risk for these experiments in our healthy volunteers.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that LV stiffening in healthy ageing occurs during the transition between youth and middle-age and is essentially complete by the age of 64. Thereafter, LV stiffening is followed by an age-associated LV volume contraction and remodelling after the age of 65.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant AG17479-02 and an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship grant 09POST2050083.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AGE

advanced glycation end-product

- EDV

end-diastolic volume; G21–34, young, 21–34 years; G35–49, early middle-age, 35–49 years; G50–64, late middle-age, 50–64 years; G≥65: ≥65 years

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- LBNP

lower-body negative pressure

- LV

left ventricular

- PCWP

pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

maximal oxygen uptake

Author contributions

N.F. contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and writing of this article. J.L.H and G.C.-R contributed to collection and interpretation of data, and critical revision of this article. P.S.B, N.K.G, S.S. and D.P. contributed to collection, analysis and interpretation of data. B.D.L contributed to conception and design of experiments, collection and interpretation of data, and critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version.

References

- Arbab-Zadeh A, Dijk E, Prasad A, Fu Q, Torres P, Zhang R, et al. Effect of aging and physical activity on left ventricular compliance. Circulation. 2004;110:1799–1805. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142863.71285.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asif M, Egan J, Vasan S, Jyothirmayi GN, Masurekar MR, Lopez S, et al. An advanced glycation endproduct cross-link breaker can reverse age-related increases in myocardial stiffness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2809–2813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040558497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenkie I, Kieser TM, Sas R, Smith ER, Tyberg JV. Evidence for left ventricular constraint during open heart surgery. Can J Cardiol. 2002;18:951–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahal NS, Lim TK, Jain P, Chambers JC, Kooner JS, Senior R. Normative reference values for the tissue Doppler imaging parameters of left ventricular function: a population-based study. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11:51–56. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemla D, Hébert JL, Coirault C, Zamani K, Suard I, Colin P, Lecarpentier Y. Total arterial compliance estimated by stroke volume-to-aortic pulse pressure ratio in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;274:H500–H505. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.2.H500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Fetics B, Nevo E, Rochitte CE, Chiou KR, Ding PA, Kawaguchi M, Kass DA. Noninvasive single-beat determination of left ventricular end-systolic elastance in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:2028–2034. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01651-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Fernandes VR, Bluemke DA, McClelland RL, Kronmal RA, Lima JA. Age-related left ventricular remodeling and associated risk for cardiovascular outcomes: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:191–198. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.819938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Xanthakis V, Sullivan LM, Lieb W, Massaro J, Aragam J, Benjamin EJ, Vasan RS. Correlates of echocardiographic indices of cardiac remodeling over the adult life course: longitudinal observations from the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010;122:570–578. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.937821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chukwu EO, Barasch E, Mihalatos DG, Katz A, Lachmann J, Han J, Reichek N, Gopal AS. Relative importance of errors in left ventricular quantitation by two-dimensional echocardiography: insights from three-dimensional echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:990–997. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauterman K, Pak PH, Maughan WL, Nussbacher A, Ariê S, Liu CP, Kass DA. Contribution of external forces to left ventricular diastolic pressure. Implications for the clinical use of the Starling law. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:737–742. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-10-199505150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza RR. Aging of myocardial collagen. Biogerontology. 2002;3:325–335. doi: 10.1023/a:1021312027486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto N, Prasad A, Hastings JL, Arbab-Zadeh A, Bhella PS, Shibata S, Palmer D, Levine BD. Cardiovascular effects of 1 year of progressive and vigorous exercise training in previously sedentary individuals older than 65 years of age. Circulation. 2010;122:1797–1805. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.973784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Föll D, Jung B, Schilli E, Staehle F, Geibel A, Hennig J, Bode C, Markl M. Magnetic resonance tissue phase mapping of myocardial motion: new insight in age and gender. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:54–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.813857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glower DD, Spratt JA, Snow ND, Kabas JS, Davis JW, Olsen CO, et al. Linearity of the Frank-Starling relationship in the intact heart: the concept of preload recruitable stroke work. Circulation. 1985;71:994–1009. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.5.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y. A clinical study of left ventricular relaxation. Circulation. 1980;62:756–763. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.62.4.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundley WG, Li HF, Willard JE, Landau C, Lange RA, Meshack BM, Hillis LD, Peshock RM. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of the severity of mitral regurgitation. Comparison with invasive techniques. Circulation. 1995;92:1151–1158. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass DA, Shapiro EP, Kawaguchi M, Capriotti AR, Scuteri A, deGroof RC, Lakatta EG. Improved arterial compliance by a novel advanced glycation end-product crosslink breaker. Circulation. 2001;104:1464–1470. doi: 10.1161/hc3801.097806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Milliken MC, Stray-Gundersen J, Buja LM, Parkey RW, Mitchell JH, Peshock RM. Estimation of human myocardial mass with MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;169:495–498. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.2.2971985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RP, Ting CT, Yang TM, Liu CP, Maughan WL, Chang MS, Kass DA. Effective arterial elastance as index of arterial vascular load in humans. Circulation. 1992;86:513–521. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan F, Green FC, Forsyth JS, Greene SA, Morris AD, Belch JJ. Impaired microvascular function in normal children: effects of adiposity and poor glucose handling. J Physiol. 2003;551:705–711. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.045351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta EG. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: part II: the aging heart in health: links to heart disease. Circulation. 2003;107:346–354. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048893.62841.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo G. Respiratory measurements of cardiac output: from elegant idea to useful test. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:428–437. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01074.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan BM, Picard MH, Leavitt M, Weyman AE. Clinical correlates and reference intervals for pulmonary artery systolic pressure among echocardiographically normal subjects. Circulation. 2001;104:2797–2802. doi: 10.1161/hc4801.100076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara LS, Matsubara BB, Okoshi MP, Cicogna AC, Janicki JS. Alterations in myocardial collagen content affect rat papillary muscle function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H1534–H1539. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky I. Assessment of diastolic function: suggested methods and future considerations. Circulation. 1984;69:836–841. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.69.4.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perhonen MA, Zuckerman JH, Levine BD. Deterioration of left ventricular chamber performance after bed rest: “cardiovascular deconditioning” or hypovolemia? Circulation. 2001;103:1851–1857. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.14.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad A, Hastings JL, Shibata S, Popovic ZB, Arbab-Zadeh A, Bhella PS, et al. Characterization of static and dynamic left ventricular diastolic function in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:617–626. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.867044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad A, Levine BD. Diastology. In: Klein A, Garcia M, editors. Clinical Approach to Diastolic Heart Failure 30. Elsevier; 2008. pp. 385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Borlaug BA, Rodeheffer RJ, Kass DA. Age- and gender-related ventricular-vascular stiffening: a community-based study. Circulation. 2005;112:2254–2262. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.541078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan MM, Weiss EP, Meyer TE, Ehsani AA, Racette SB, Villareal DT, et al. The effects of caloric restriction- and exercise-induced weight loss on left ventricular diastolic function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1174–H1182. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01236.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche AF, Heymsfield SB, Lohman TG. Human Body Composition. Champain, III: Human Kinetics; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sangaralingham SJ, Huntley BK, Martin FL, McKie PM, Bellavia D, Ichiki T, et al. The aging heart, myocardial fibrosis, and its relationship to circulating C-type natriuretic peptide. Hypertension. 2011;57:201–207. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki R, Yamagiwa H, Ichikawa S, Ito A, Yamagata S. Aging and scar tissue in human heart muscle. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1975;116:253–258. doi: 10.1620/tjem.116.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Yao Q, Zhu J, Luo B, Liang S. Age-related variation in the interstitial tissues of the cardiac conduction system; and autopsy study of 230 Han Chinese. Forensic Sci Int. 1999;104:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(99)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui X, LaMonte MJ, Laditka JN, Hardin JW, Chase N, Hooker SP, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness and adiposity as mortality predictors in older adults. JAMA. 2007;298:2507–2516. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.21.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor RG, Haley RW, Willett DL, Peshock RM, Vaeth PC, Leonard D, Basit M, et al. The Dallas Heart Study: a population-based probability sample for the multidisciplinary study of ethnic differences in cardiovascular health. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1473–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan SF, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM. The RAGE axis: a fundamental mechanism signaling danger to the vulnerable vasculature. Circ Res. 2010;106:842–853. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]