Abstract

The present study examines several types of social anxiety that may be associated with the onset of alcohol use in middle school students, and whether the relationship differs by sex and grade. Students in the seventh and eighth grades (N = 2621) completed the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents and a measure of lifetime drinking via school-wide surveys. Distinct aspects of social anxiety were associated with higher and lower rates of onset of alcohol use. A high level of fear of negative evaluation was associated with drinking initiation in boys and girls, while girls who reported no social anxiety or distress in new situations were more likely than other groups to have started drinking by early adolescence. Youth with either very low or very high levels of generalized anxiety had higher rates of drinking than youth with scores in between. These findings suggest that the relationship between social anxiety and initiation of alcohol use is complex and varies by type of anxiety symptomatology.

Keywords: alcohol use, adolescent, social anxiety

Early adolescence is a developmental period marked by physical, cognitive, and social transitions. The onset of puberty signifies the beginning of the physical transition from childhood into adulthood and is also associated with significant emotional and cognitive changes. At the same time, entry into middle school is an environmental transition that tends to increase the influence of social and interpersonal relationships on psychosocial development. The convergence of these major life transitions require an ability to adapt to the biological changes associated with puberty while adjusting to the increased social demands related to changes in the relative importance of peer and parental relationships (Windle, et al., 2008). Many youth develop emotional and behavioral problems during this phase of development. For example, social anxiety increases in early adolescence (Vernberg, Abwender, Ewell, & Beery, 1992; Inderbitzen, Walters, & Bukowski, 1997), when peer relationships become of paramount importance (e.g., Hartup, 1992; Inderbitzen, 1994). Many early adolescents also experiment with alcohol use, with approximately 40% of 8th graders reporting lifetime use in a national survey (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2008). The current study examines whether specific aspects of social anxiety are associated with drinking initiation in youths.

The self-medication hypothesis (Khantzian, 1985) predicts that socially anxious youth will attempt to reduce tension or anxiety by drinking when they find themselves in a social situation where alcohol is present (Kushner, Sher, Wood, & Wood, 1994). Retrospective studies of adults with comorbid social anxiety disorder and alcohol dependence indicate that social anxiety precedes alcohol use (Buckner, Timpano, Zvolensky, Sachs-Ericsson, & Schmidt, 2008; Kushner, Sher, & Beitman, 1990). However, the relationship between social anxiety and adolescent drinking is unclear: in clinical samples of youth social phobia has up to a 33% comorbidity rate with alcohol and drug use disorders, (Clark, Bukstein, Smith, & Kaczynski, 1995; Hovens, Cantwell, & Kiriakos, 1994), yet in community samples social anxiety is associated with lower rates of alcohol use (Myers, Aarons, Tomlinson, & Stein, 2003; Wu et al., 2010).

The different relationships found between social anxiety and alcohol involvement in clinical and community samples of adolescents may be due to differences in the way social anxiety is measured. Social anxiety and alcohol use and problems are consistently linked in youth diagnosed with social phobia, a DSM-IV psychiatric disorder. In these studies a diagnosis of social phobia is given to adolescents whose anxiety score is above a certain threshold. Yet studies of youth in schools and the community that measure social anxiety using a continuous scale report inconclusive results. Together, these results may indicate a non-linear, threshold relationship between social anxiety and adolescent drinking. Developmental research indicates that social anxiety increases in early adolescence (Inderbitzen et al., 1997; Vernberg et al., 1992), as self-conscious emotions increase (Elkind, 1967). Self-conscious emotions have been shown to have social benefits during adolescence, including reinforcing positive social behaviors and reparation of social errors (Yee & Flanagan, 1985). There is also research suggesting that a lack of self-conscious emotion is a contributing cause of problem behavior (Keltner, 1995). Therefore, in early adolescence the experience of some social anxiety is normative and expected as youth become increasingly self-conscious. A nonlinear relationship between social anxiety and alcohol use is consistent with this developmental framework of adolescent self-consciousness and social anxiety: adolescents most at risk for early drinking may be those at the extremes, with either high (including youth with social phobia) or very low levels of social anxiety.

Additionally, previous studies that have examined the relationship between social anxiety and alcohol use in adolescence have considered social anxiety to be a one-dimensional construct. However, it may be useful to examine whether certain dimensions of social anxiety are uniquely associated with alcohol initiation in early adolescents. Watson and Friend (1969) identified two dimensions of social anxiety: fear of negative evaluation by others (FNE) and social avoidance and distress experienced in the presence of others (SAD).

Fear of negative evaluation by one’s peers in a situation where alcohol is present may influence adolescents to drink due to peer pressure and a desire to fit in if drinking is perceived as normal or expected behavior. While the relationship between peer pressure and adolescent alcohol involvement has been well established, no studies have examined the specific role of FNE in adolescent alcohol use. However, FNE has been found to be positively correlated with drinking in college and adult samples (Lewis & O’Neill, 2000; Stewart, Morris, Mellings, & Komar, 2006).

In contrast, social avoidance behavior associated with shy, socially anxious youth (Rubin & Asendorpf, 1993; Vernberg et al., 1992) may decrease risk of initiation of alcohol use in social settings. In the same studies in which FNE was found to predict alcohol use, Lewis and O’Neill (2000) found that shyness was unrelated to drinking in their adult sample, and Stewart et al., (2006) found that SAD was negatively correlated with drinking frequency in college students. This evidence suggests that FNE and SAD are associated with drinking behavior in different ways in adults.

Social avoidance and distress has been further differentiated into two separate dimensions in children and adolescents: new/unfamiliar and generalized (Buss, 1991; Asendorpf, 1993). The first type of social anxiety is characterized by wariness and behavioral inhibition with strangers and in unfamiliar situations, while the second type includes social anxiety and withdrawn behavior with familiar peers. LaGreca and Stone (1993) note that social avoidance and inhibition in new situations is less problematic for the development of normal socialization and friendship development than the more pervasive avoidance seen in youth with high levels of generalized social anxiety. Middle school is a critical time for exposure to new social situations, and high levels of the generalized form of SAD may put adolescents at risk for drinking alcohol to self-medicate anxiety in social contexts with peers. Conversely, experiencing some SAD in new/unfamiliar situations may protect youth from early onset alcohol use if they consider drinking alcohol to be a risky behavior, while a complete lack of anxiety in new situations may be associated with more alcohol experimentation. Although no studies have specifically examined the relationship between SAD and alcohol use in adolescents, behavioral inhibition has been found to protect against substance use (Fergusson & Horwood, 1999; Shedler and Block, 1990).

The purpose of this investigation is to examine the different processes by which social anxiety may be associated with the initiation of alcohol use in a sample of middle school students. In order to delineate unique relationships between different aspects of social anxiety and drinking, we tested three specific components of social anxiety: fear of negative evaluation (FNE), social anxiety and distress experienced in new or unfamiliar situations (SAD-N), and generalized social anxiety and distress (SAD-G). We hypothesized nonlinear relationships, such that the impact of social anxiety would only be seen at the extreme ends. Specifically, the highest level of FNE and SAD-G, and the lowest level of SAD-N, were hypothesized to be associated with higher rates of drinking initiation than all other levels. We also tested the social anxiety composite score, and predicted that its association with drinking would be modest compared to the separate tests of its subscales. Given that sex differences have been found in social anxiety such that girls report higher levels of FNE and SAD-N but not SAD-G compared to boys (Inderbitzen-Nolan & Walters, 2000; LaGreca & Lopez, 1998; Myers, Stein, & Aarons, 2002) and sex differences have been found in the relations between social anxiety and alcohol use disorders (Buckner & Turner, 2009), and marked grade differences are seen in alcohol use we explored sex and grade (seventh vs. eighth grade) differences in our analyses.

Method

Participants

In the spring of 2002, 2,621 seventh and eighth grade students between the ages of 11–14 in four San Diego County middle schools completed a survey of health-related behaviors. Respondents were dropped from the analyses if they did not provide data on drinking behavior (n = 5) or social anxiety symptoms (n = 56). This resulted in a final sample of 2,560 youth evenly split by sex (48.6% female) and grade (51.5% seventh and 48.5% eighth grade) who identified themselves as Caucasian (57.8%), Asian-American (9.9%), African-American (2.3%), Hispanic (12.1%), American Indian (2.8%), Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander (2.6%), Other (10.0%), and Multiracial (2.5%). Youth who were dropped from the analyses did not differ from the final sample on age, sex, or grade. Chi-square analysis could not be used to examine possible ethnic differences between youth retained and dropped due to cell counts less than 5 in 20% of the cells. Characteristics of the final sample are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by sex and grade (N = 2560)

| 7th Grade Girls (n = 647)

|

8th Grade Girls (n = 597)

|

7th Grade Boys (n = 672)

|

8th Grade Boys (n = 644)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [M (SD)] | 12.6 (0.5) | 13.5 (0.5) | 12.7 (0.5) | 13.6 (0.5) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 57.3% | 58.1% | 58.9% | 56.7% |

| Asian-American | 11.6% | 9.1% | 8.1% | 10.8% |

| African-American | 1.7% | 2.2% | 2.1% | 3.1% |

| Hispanic | 11.3% | 14.7% | 12.2% | 10.3% |

| American Indian | 3.1% | 2.9% | 2.7% | 2.5% |

| Hawaiian | 2.7% | 2.4% | 2.6% | 3.0% |

| Other | 10.0% | 7.8% | 11.9% | 10.2% |

| Multiracial | 2.3% | 2.9% | 1.5% | 3.4% |

| Ever Drank Alcohol? | 21.9%a | 41.9%b | 29.8%c | 48.6%d |

| Social Anxiety | ||||

| FNE [M (SE)] | 17.8 (0.27)a | 18.0 (0.28)a | 16.4 (0.27)b | 16.3 (0.27)b |

| SAD-G [M (SE)] | 6.7 (0.12)a | 6.9 (0.13)ab | 7.3 (0.12)b | 7.3 (0.13)b |

| SAD-N [M (SE)] | 14.0 (0.19)a | 13.8 (0.20)ab | 13.5 (0.19)ab | 13.2 (0.20)b |

| SAS-A [M (SE)] | 38.3 (0.53)a | 38.7 (0.55)a | 37.2 (0.52)a | 36.8 (0.53)a |

Note: FNE = Fear of Negative Evaluation; SAD-G = Generalized Social Anxiety and Distress; SAD-N = Social Anxiety and Distress in New/Unfamiliar Situations; SAS-A = Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (composite score) from La Greca (1999). Means and percentages with different superscripts across rows are significantly different (range = p<.05 – p<.001).

Measures

Alcohol use

Initiation of alcohol use was measured with a single categorical item (During your LIFE, how many times have you had at least one drink of alcohol [regular size can/bottle of beer or wine cooler, glass of wine, shot of liquor, etc.]: 0 (never), 1 (1 to 2 times), 2 (3 to 5 times), 3 (6–10 times), 4 (11–50 times), and 5 (51+ times)). This variable was dichotomized so that youth were categorized as having ever drunk alcohol (yes/no).

Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents-Revised (SAS-A)

The SAS-A (La Greca & Lopez, 1998) has 22 items, 18 anxiety-related and 4 filler, assessing social preferences and activities. It is divided into three subscales: FNE (e.g., “I worry about what others think of me”), SAD-N (e.g., “I get nervous when I meet new people”), and SAD-G (e.g., “I feel shy even with peers I know well”). Youth indicated on a 5-point scale how much each item characterized themselves. Scores from the three subscales were summed to form a total score with a range of 18–90, with higher scores reflecting greater social anxiety. SAS-A has been found to have good internal consistency (Ginsberg, La Greca, & Silverman, 1998; La Greca and Stone, 1993) and reliability and validity (Inderbitzen-Nolan & Walters, 2000).

Demographics

Respondents completing the survey were asked to provide information about age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Ethnic differences were found in drinking initiation (χ 2 [df = 7] = 90.96, p < .001). Students who identified as African American were most likely to report lifetime drinking (54.2%), while Asian American students reported the least incidence of drinking (16.9%). Asian Americans also reported higher SAD-N scores compared to the other ethnic groups (F [df = 7] = 2.37, p = .02). Due to these differences we decided to include ethnicity as a covariate in our models.

Procedure

To obtain parental consent, consent forms were posted certified mail to all students’ homes. Parents were informed that completion of the survey was voluntary and were given the opportunity to notify the school if they did not want their child to participate. Parents who did not wish their children to participate could notify the school verbally or in writing (0.5%). Trained research staff from the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) administered the survey in the normal classroom setting. Students were informed that the surveys were confidential and anonymous, and that no identifying information was collected, after which they provided assent to participate in the survey. Only youth with both parental consent and child assent were included into the study. As this survey was part of the school-wide assessment of health-related behaviors, there was a high level of student involvement (99%). The participating school districts and the UCSD Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Analytic Strategy

Our a priori hypotheses included the possibility that the anxiety measures have threshold and/or non-monotonic relationships with lifetime drinking. Logistic regression does not accommodate non-monotic relationships. Piece-wise logistic regression was an option, but its use is complicated by the requirement to establish the number and location of knots from the same data being fit to the regression model. We opted to divide scores on the SAS-A and its subscales into quantiles, because this approach allows the model to be structured without relying on patterns in the data, is the most flexible in fitting thresholds and non-monotonic curvilinear response, and provides a simple interpretation. In this report seven quantiles were used to examine whether extremely low or high scores increased likelihood of alcohol use. Separate logistic regressions were used to determine whether SAS-A subscales and the composite score quantiles predict initiation of alcohol use. All models were re-run with anxiety scores divided into five and nine quantiles and results were found to be consistent. The predictors in the first regression were: SAS-A composite score, sex, grade, all 2-way interactions (SAS-A x sex; SAS-A x grade; sex x grade), the three-way interaction (SAS-A x sex x grade), and ethnicity. The remaining three regressions were modeled similarly with FNE, SAD-N, and SAD-G. In each regression, the quantile with the lowest base-rate was used as the reference group when reporting odds ratios and predicted probabilities. Models were estimated using maximum likelihood and the significance of the total effect for each factor evaluated with a likelihood ratio test comparing nested models (Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, 2005). Categorical associations were tested with Chi-squared tests. Relationships between demographic factors and the subscales were tested with ANOVA’s. All reported confidence intervals are at the 95% level.

Results

Table 1 provides information regarding the demographic, social anxiety, and alcohol use characteristics of the sample. Social anxiety scores were consistent with previous studies of seventh and eighth grade girls and boys. Grade and sex were found to be associated with the initiation of alcohol use (χ 2 [df = 3] = 122.64, p < .001) and sex differences were seen in mean scores on the anxiety subscales. Girls reported higher levels of FNE (F [df = 3] = 11.34, p < .001), seventh grade girls reported higher SAD-N than eighth grade boys (F [df = 3] = 3.24, p = .02), and boys reported higher levels of SAD-G than seventh grade girls (F [df = 3] = 6.22, p < .001). However, boys’ and girls’ SAS-A total score means did not statistically differ from one another. Correlations between the three subscales ranged from .58–.63.

The omnibus model tests and overall effect tests of the predictors in the logistic regressions are provided in Table 2. Sex and grade and their interaction were entered into the regression models to determine whether these variables predict alcohol use when social anxiety is being simultaneously tested. Being male and being in the eighth grade significantly predicted having consumed alcohol in one’s lifetime in all four regression models. The odds ratios for the sex (female reference) ranged from 1.90 (CI = 1.05 – 3.42) to 2.84 (CI = 1.40 – 5.76) and the grade (seventh grade reference) ranged from 2.30 (CI = 1.12 – 4.73) to 4.14 (CI = 2.05 – 8.38). None of the sex x grade interactions were statistically significant. There was also an overall effect of ethnicity in the four models. Compared to Caucasian students, Asian students were less likely to drink in all models, with OR’s ranging from 0.36 (CI = 0.18 – 0.74) to 0.38 (CI = 0.20 – 0.74). African American and Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander students drank the most, with OR’s ranging from 2.25 (CI = 1.02 – 4.96) to 2.33 (CI = 1.02 – 5.36) for African Americans and 2.25 (CI = 1.05 – 4.83) to 2.42 (CI = 1.10 – 5.31) for Hawaiian/ Pacific Islanders when using Caucasians as the reference group.

Table 2.

Effect tests for prediction of initiation of drinking by subtypes of social anxiety

| Variable | FNE (n = 2450) | SAD-N (n = 2473) | SAD-G (n = 2511) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | χ2 | p-value | df | χ2 | p-value | df | χ2 | p-value | |

| Sex | 1 | 19.06 | .00 | 1 | 21.14 | .00 | 1 | 16.99 | .00 |

| Grade | 1 | 106.48 | .00 | 1 | 85.87 | .00 | 1 | 74.72 | .00 |

| Sex * Grade | 1 | 0.26 | .61 | 1 | 0.15 | .70 | 1 | 0.14 | .71 |

| Scale | 6 | 24.02 | .00 | 6 | 28.41 | .00 | 6 | 21.83 | .00 |

| Scale * Sex | 6 | 5.35 | .50 | 6 | 16.97 | .01 | 6 | 6.05 | .42 |

| Scale * Grade | 6 | 8.13 | .23 | 6 | 5.71 | .46 | 6 | 12.22 | .06 |

| Scale * Sex * Grade | 6 | 10.98 | .09 | 6 | 6.25 | .40 | 6 | 7.85 | .25 |

| Ethnicity | 7 | 88.79 | .00 | 7 | 85.66 | .00 | 7 | 82.77 | .00 |

Note: FNE = Fear of Negative Evaluation; SAD-G = Generalized Social Anxiety and Distress; SAD-N = Social Anxiety and Distress in New/Unfamiliar Situations. The overall model tests of the logistic regression analyses are as follows: FNE = (χ2 [df = 34] = 252.99, p<.001); SAD-N = (χ 2 [df = 34] = 261.76, p<.001); SAD-G = (χ 2 [df = 34] = 260.93, p<.001). Statistically significant parameters (p ≤ .05) are highlighted in bold.

The general measure of social anxiety was first examined for association with initiation of drinking. The overall model test was significant (χ2 [df = 34] = 226.18, p<.001). Additionally, the total effect of SAS-A with its interaction terms was found to have a significant overall association with drinking initiation (LR χ 2 [df = 24] = 41.92, p =. 01). Consistent with expectations, neither the separate main effect nor interaction parameters of SAS-A were found to be individually significant (p’s > .10).

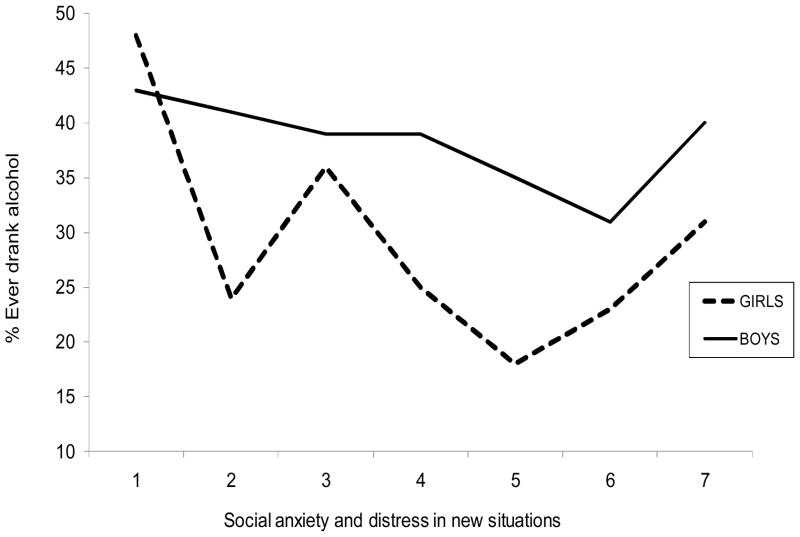

We next tested whether a high level of fear of negative evaluation was associated with a greater likelihood of drinking. The overall effects of FNE in the model significantly predicted drinking (LR χ 2 [df = 24] = 50.91, p = .001) and our hypothesis that a high level of FNE would predict drinking initiation was supported (Figure 1). Youth in quantile seven were 50% more likely to drink than youth in the reference group with a predictive probability (P) of 0.45 (CI = 0.40 – 0.51) compared to 0.30 (CI = 0.25 – 0.34), and were significantly more likely to drink than all other groups as well (p < .05 – p < .001). None of the other groups were significantly different from one another. There were no significant interactions between FNE, sex, or grade (Table 2).

Figure 1.

The predicted probabilities for the percentage of youth who ever drank alcohol as a function of level of fear of negative evaluation (FNE) and generalized social anxiety and distress (SAD-G). Level of anxiety was measured by dividing scores into seven quantiles.

Note: FNE raw scores range from 8 to 40 and SAD-G raw scores range from 4 to 20.

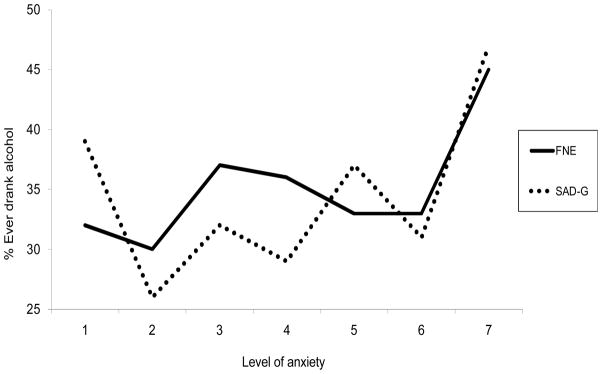

Next we determined whether a low level of social anxiety and distress in new situations was associated with an increased risk of having initiated alcohol use. The overall effects of SAD-N in the model (LR χ 2 [df = 24] = 57.62, p < .001) and the interaction of SAD-N and sex significantly predicted initiation of alcohol use (Table 2). Our hypothesis was supported in girls, but not in boys (Figure 2). Girls in quantile one (P = 0.44; CI = 0.35 – 0.53) were more than twice as likely to have drunk as girls in the reference group (P = 0.19; CI = 0.07 – 0.31), and were significantly more likely to drink than all other groups as well (p < .05 – p < .001). Girls in quantile three (P = 0.34; CI = 0.26 – 0.43) were significantly more likely to drink compared to the reference group only. There were no significant differences among quantiles in boys.

Figure 2.

Sex differences in the predicted probabilities for the percentage of youth who ever drank alcohol as a function of level of social anxiety and distress in new/unfamiliar situations (SAD-N). Level of anxiety was measured by dividing scores into seven quantiles.

Note: SAD-N raw scores range from 6 to 30.

Finally, we tested whether a high level of generalized social anxiety and distress predicted a greater risk of drinking initiation. The overall effects of SAD-G in the model (LR χ 2 [df = 24] = 49.51, p = .002) significantly predicted initiation of alcohol use (Table 2). As expected, youth in quantile seven (P = 0.43; CI = 0.37 – 0.49) were significantly more likely to drink than youth in the reference group, which was quantile two (P = 0.27; CI = 0.23 – 0.33), and were also significantly more likely to drink than youth in quantiles three through six (p < .05 – p < .001). Interestingly, youth in the first quantile also had significantly higher rates of drinking compared to the reference group (P = 0.37; CI = 0.32 – 0.40). Quantiles one and seven were not significantly different from one another (Figure 1).

Discussion

Early adolescence is an important time in which to study the relationship between social anxiety and the initiation of alcohol use as they both increase during this developmental period (e.g., Johnston et al., 2008; Inderbitzen et al., 1997; Partnership for a Drug Free America, 1999; Pride Surveys, 2009; Vernberg et al., 1992). The findings of this study indicate that social anxiety has a complex relationship with youths’ likelihood to begin drinking alcohol by early adolescence. Results suggest nonlinear relationships between social anxiety subscales and alcohol use, as well as specificity in the direction of the risk association. Although the three subtypes of social anxiety measured here are consistently found to be correlated (Inderbitzen-Nolan & Walters, 2000; Myers et al, 2002), they showed different patterns in their relationship with drinking initiation. Interestingly, as in some previous studies (e.g., Wu et al., 2010), the composite social anxiety measure was not found to significantly predict initiation of drinking. This is most likely due to the opposite directions of the different subscales’ associations with drinking cancelling out the effect measured in the composite score.

Consistent with expectations, we found that boys and girls who reported the highest level of FNE were more likely to have drunk alcohol in their lifetime than youth without extreme social-evaluative fears. Fear of negative evaluation puts adolescents at unique risk for early onset of drinking if they also have a high perception of peer drinking (Anderson, Tomlinson, Robinson, & Brown, in press). FNE can increase risk for drinking through higher susceptibility to peer pressure or simply a desire to fit in. Marmorstein, White, Loeber, and Stouthamer-Loeber (2010) found that boys high in social anxiety had a younger age of onset of alcohol use; however, the association disappeared when co-occurring delinquent behavior was accounted for. Other studies have found an association between anxiety and externalizing behavior (Abrantes, Brown, & Tomlinson, 2004; Clark, Jacob, & Mezzich, 1994; Russo & Beidel, 1994). Social skills deficits seen in highly socially anxious youth increases the risk for these adolescents to be neglected and rejected by their peers, which in turn puts these youth at risk for joining more deviant “out groups” who engage in deviant behaviors such as early alcohol involvement (Connell, Dishion, & Deater-Deckard, 2006).

An intriguing finding from the present study is that girls who reported that they experienced little or no social anxiety and distress in new or unfamiliar situations were more likely to have started drinking than all other levels of SAD-N. It indicates that this constellation of social anxiety symptoms may have a protective effect, such that experiencing any social anxiety and distress in new or unfamiliar situations lessens the likelihood that girls will start to drink in middle school. Given the similarity between this construct and behavioral inhibition, which is a form of withdrawal characterized by the avoidance of novel social situations (e.g., Kagan & Reznick, 1986), it may be that this subscale is actually measuring behavioral inhibition. Initiating alcohol use is a novel experience that girls in particular seem to be especially at risk for engaging in earlier if they don’t experience any of this type of anxiety. While prior studies found a negative correlation between behavioral inhibition and alcohol use in adolescents (Shedler & Block, 1990; Stice, Myers, & Brown, 1998), this study found that the most robust association between SAD-N and drinking initiation is at the extreme low end. In future studies it is important to determine whether extremely low scores on the SAD-N are associated with a high level of disinhibition. There was no discernable relationship between SAD-N and drinking initiation among boys and this may be due in part to differences in the social context of middle school drinking initiation for boys and girls. For example, girls are more likely to hang out with older boys than boys are to hang out with older girls, and girls who date older boys are more than twice as likely to drink compared to girls who date boys their own age (The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 2004).

Our hypothesis that youth with the highest level of generalized social anxiety and distress would have the highest drinking rate was supported. However, the lowest level of SAD-G was also associated with elevated likelihood of drinking, and there was no statistically significant difference between the highest and lowest levels, indicating a U-shaped function. Important differences are seen in the relationships between the two subtypes of SAD. First, while low SAD-N was only associated with increased drinking rates in girls, low SAD-G was associated with elevated drinking in the entire sample. This indicates that in girls, a lack of any type of social anxiety and distress is associated with a risk for early onset of drinking. In contrast, the relationship between type of SAD and drinking is more specific in boys, as only a lack of SAD-G predicts drinking. Furthermore, high SAD-G, but not SAD-N, was found to predict drinking in boys and girls. This may not be surprising, since the generalized type of social anxiety is associated with more severe emotional and social impairments compared to social anxiety experienced in new situations (La Greca & Lopez, 1998). In these youth, the natural tendency toward behavioral inhibition may be overshadowed by the desire to self-medicate with alcohol when in social situations where alcohol is present. Although further research needs to be conducted to determine causal mechanisms for these findings, our results may suggest that subtypes of at-risk youth are already beginning to emerge- low-anxious sensation-seekers and high-anxious self-medicators (e.g., Zucker, 1994).

There are several limitations to this study. While social anxiety is generally found to precede alcohol use and problems (e.g, Buckner, et al., 2008), the cross-sectional design of the present study precludes us from making causal inferences. An important next step in evaluating the risk or protective nature of these different aspects of social anxiety is to replicate these findings in a longitudinal study. It will also be important to measure the relationship between social anxiety and quantity, frequency, and age of onset of alcohol use to determine whether the relationships found between social anxiety and onset of drinking will hold when looking at other alcohol use measures. Although we included ethnicity as a covariate in the present study, future studies should determine whether there are important interactions between social anxiety and ethnicity. Additionally, it would have been useful to include personality/ temperament variables (e.g., sensation-seeking, impulsivity) and questions about behavior (e.g., other deviant behaviors) to reveal possible correlates with having extremely high or low social anxiety and how these factors may interact with social anxiety to increase or decrease the risk of early initiation of drinking. Furthermore, different aspects and levels of social anxiety in early adolescents may result in decision-making processes that lead to exposure to situations in which they are put at risk for drinking. Future research should also examine drinking contexts to determine the situations in which socially anxious youth are most likely to drink.

Our findings shed light on two factors that may help to explain the discrepancies in the literature regarding social anxiety’s impact on alcohol use during adolescence. First, previous studies of youth in community samples searched for linear associations between social anxiety and alcohol use, while the findings of the current study indicate that the relationship between these variables is likely non-linear. Second, the direction of the relationship depends on the specific aspect of social anxiety in question. This is consistent with the findings of Stewart, et al. (2006), in which FNE was positively associated with drinking problems in undergraduate college students, while social avoidance and distress was negatively related to drinking frequency. This study underscores the need to develop prevention efforts that more specifically target youths according to their unique social anxiety risk factors. For example, high FNE youth may particularly benefit from a social intervention program that promotes self esteem and includes assertiveness training to improve skills such as drinking refusal self-efficacy (Young & Oei, 1993). Primary prevention programs that target low SAD-N girls may include education on the consequences of use and increased availability of alternative social activities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a National Research Service Award pre-doctoral fellowship (F31 AA 13461) and a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA 12171).

References

- Abrantes AM, Brown SA, Tomlinson K. Psychiatric comorbidity among inpatient substance abusing adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2004;13(2):83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KG, Tomlinson KL, Robinson JM, Brown SA. Friends or foes: social anxiety, peer affiliation, and drinking in middle school. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.61. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB. Abnormal shyness in children. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1993;34(7):1069–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Timpano K, Zvolensky MJ, Sachs-Ericsson N, Schmidt NB. Implications of comorbid alcohol dependence among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25:1028–1037. doi: 10.1002/da.20442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Turner RJ. Social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol use disorders: A prospective examination of parental and peer influences. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;100:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH. The EAS theory of temperament. In: Strelau J, Angleitner A, editors. Explorations in temperament: International perspectives on theory and measurement. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Bukstein OG, Smith MG, Kaczynski NA. Identifying anxiety disorders in adolescents hospitalized for alcohol abuse or dependence. Psychiatric Services. 1995;46(6):618–620. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.6.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Jacob RG, Mezzich A. Anxiety and conduct disorders in early onset alcoholism. In: Babor T, editor. Types of alcoholics: Evidence from clinical, experimental, and genetic research. New York, NY: New York Academy of Sciences; 1994. pp. 181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Dishion TJ, Deater-Deckard K. Variable- and person-centered approaches of early adolescent substance use: Linking peer, family, and intervention effects with developmental trajectories. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52(3):421–448. [Google Scholar]

- Elkind D. Egocentrism in Adolescence. Child Development. 1967;38:1025–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Prospective childhood predictors of deviant peer affiliations in adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1999;40(4):581–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg GS, La Greca AM, Silverman WK. Social anxiety in children with anxiety disorders: relation with social and emotional functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26(3):175–185. doi: 10.1023/a:1022668101048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW. Childhood social development: Contemporary perspectives. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1992. Friendships and their developmental significance; pp. 175–205. [Google Scholar]

- Hovens JGFM, Cantwell DP, Kiriakos R. Psychiatric comorbidity in hospitalized adolescent substance abusers. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33(4):476–483. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199405000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inderbitzen HM. Adolescent peer social competence: A critical review of assessment methodologies and instruments. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;16:227–259. [Google Scholar]

- Inderbitzen HM, Walters KS, Bukowski AL. The role of social anxiety in adolescent peer relations: Differences among sociometric status groups and rejected subgroups. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26(4):338–348. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2604_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inderbitzen-Nolan HM, Walters KS. Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents: Normative data and further evidence of construct validity. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29(3):360–371. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. NIH Publication No 08-6418A. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008. Monitoring the Future National Survey on Drug Use, 1975–2007. Volume I: Secondary School Students. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS. Shyness and temperament. In: Jones WH, Cheek JM, Briggs SR, editors. Shyness: Perspectives on research and treatment. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D. Signs of appeasement: Evidence for the distinct displays of embarrassment, amusement, and shame. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:441–454. [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian E. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: Focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner M, Sher K, Beitman B. The relation between alcohol problems and the anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:685–695. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Sher KJ, Wood MD, Wood PK. Anxiety and drinking behavior: moderating effects of tension-reduction alcohol outcome expectancies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1994;18(4):852–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Lopez N. Social anxiety among adolescents: Linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26(2):83–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1022684520514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Stone WL. Social Anxiety Scale for Children--Revised: Factor structure and concurrent validity. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1993;22(1):17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B, O’Neill k. Alcohol expectancies and social deficits relating to problem drinking among college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:295–299. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, White HR, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Anxiety as a predictor of age at first use of substances and progression to substance use problems among boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:211–224. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9360-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MG, Aarons GA, Tomlinson KL, Stein MB. Social anxiety, negative affectivity, and substance use among high school students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(4):277–283. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MG, Stein MB, Aarons GA. Cross validation of the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents in a high school sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16(2):221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) at Columbia University. National Survey of American Attitudes on Substance Abuse IX: Teen Dating Practices and Sexual Activity. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.casacolumbia.org/templates/PressReleases.aspx?articleid=366&zoneid=61.

- Partnership for a Drug-Free America. 1998 Partnership Attitude Tracking Study: Children in grades 4 through 6, teens in grades 7 through 12, parents of children under 19, Research Results (Release Date: April 26, 1999) New York: Partnership for a Drug-Free America; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pride Surveys. 2008–09 National Survey- Grades 6 thru 12. 2009 Aug; Retrieved from http://www.pridesurveys.com/customercenter/us08ns.pdf.

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Asendorpf JB. Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood: Conceptual and definitional issues. In: Rubin KH, Asendorpf JB, editors. Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1993. pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Russo MF, Beidel DC. Comorbidity of childhood anxiety and externalizing disorders: Prevalence, associated characteristics, and validation issues. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14(3):199–221. [Google Scholar]

- Shedler J, Block J. Adolescent drug use and psychological health: a longitudinal inquiry. American Psychologist. 1990;45(5):612–630. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Morris E, Mellings T, Komar J. Relations of social anxiety variables to drinking motives, drinking quantity and frequency, and alcohol-related problems in undergraduates. Journal of Mental Health. 2006;15(6):671–682. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Myers MG, Brown SA. A longitudinal grouping analysis of adolescent substance use escalation and de-escalation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12(1):14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM, Abwender DA, Ewell KK, Beery SH. Social anxiety and peer relationships in early adolescence: a prospective analysis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1992;21(2):189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Friend R. Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1969;33:448–457. doi: 10.1037/h0027806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Spear LP, Fuligni AJ, Angold A, Brown JD, Pine D, Smith GT, Giedd J, Dahl RE. Transitions into underage and problem drinking: Developmental processes and mechanisms between 10 and 15 years of age. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 4):S273–S289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Goodwin RD, Fuller C, Liu X, Comer JS, Cohen P, Hoven CW. The relationship between anxiety disorders and substance use among adolescents in the community: specificity and gender differences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(2):177–188. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9385-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee DK, Flanagan C. Family environments and self-consciousness in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1985;5(1):59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Young RM, Oei TP. Grape expectations: the role of alcohol expectancies in the understanding and treatment of problem drinking. International Journal of Psychology. 1993;28:337–364. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Pathways to alcohol problems and alcoholism: A developmental account of the evidence for multiple alcoholisms and for contextual contributions to risk. In: Zucker RA, Boyd G, Howard J, editors. The development of alcohol problems: Exploring the biopsychosocial matrix of risk. Vol. 26. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1994. pp. 255–289. NIAAA Research Monograph. [Google Scholar]