Abstract

The introduction of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) in the late 1980s combined with anthracycline-based chemotherapy has revolutionized the prognosis of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) with more than 90% complete response rates and cure rates of approximately 80%. The subsequent advent of arsenic trioxide (ATO) in 1990s and progress in the treatment of APL have changed its course from a highly fatal to a highly curable disease. Despite the dramatic improvement in clinical outcome of APL, treatment failure still occurs due most often to early death. Relapse has become increasingly less frequent, most commonly occurring in patients with high-risk disease. A major focus of research for the past decade has been to develop risk-adapted and rationally targeted nonchemotherapy treatment strategies to reduce treatment-related morbidity and mortality to low- and intermediate-risk or older patients while targeting more intensive or alternative therapy to those patients at most risk of relapse. In this review, emerging new approaches to APL treatment with special emhasis on strategies to reduce early deaths, risk-adapted therapy during induction, consolidation and maintenance, as well as an overview of current and future clinical trials in APL will be discussed.

Keywords: acute promyelocytic leukemia

Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a subtype of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) accounting for 10-15% of the approximately 12,330 adults diagnosed with AML in the United States each year [Tallman and Altman, 2008]. The disease is characterized by the distinctive morphology of blast cells [Bennett et al. 1980, 1976], a life-threatening coagulopathy [Tallman and Kwaan, 1992], and a specific reciprocal translocation t(15;17) [Rowley et al. 1977], which fuses the PML (promyelocyte) gene on chromosome 15 to the RAR-α (retinoic acid receptor-α) gene on chromosome 17 [Grignani et al. 1993]. While the vast majority of APL cases contain t(15;17)(q22;q11.12), several variant translocations involving RAR-α have been identified including t(11;17) and t(5;17). Distinguishing between these translocations is important because patients with some variants are almost invariably resistant to all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA).

Prior to the introduction of ATRA, APL was among the most fatal subtypes of AML at presentation or during induction, primarily because of an associated complex and often catastrophic bleeding disorder [Tallman and Altman, 2008]. However, since the advent of ATRA in the late 1980s and arsenic trioxide (ATO) in the late 1990s, progress in the treatment of APL has changed its course from a highly fatal to a highly curable disease.

Despite the dramatic improvement in the treatment outcome of APL, treatment failure still occurs due most often to early death. Relapse has become increasingly less frequent, most commonly occurring in patients with high-risk disease. A major focus of research for the past decade has been to develop a risk-adapted treatment strategy to reduce treatment-related morbidity and mortality in low- and intermediate- risk or older patients while targeting more intensive or alternative therapy to those patients at most risk of relapse.

In this review, the treatment of APL is discussed with special emphasis placed on strategies to further increase the cure rate by reducing the early death rate and by adopting risk-adapted treatment approach during induction, consolidation, and maintenance.

Induction

The evolution of induction therapy in APL

Prior to ATRA, APL was treated in the same way as other forms of AML. Induction consisted of an anthracycline and cytarabine, yielding complete remission (CR) rates of 65-80% of newly diagnosed cases of APL [Head et al. 1994; Fenaux and Degos, 1991; Cunningham et al. 1989]. The remaining patients sustained early death, mainly from bleeding complications due to the coagulopathy or resistance to chemotherapy. Adverse prognostic factors for CR achievement or fatal hemorrhage included elevated blast or promyelocyte counts, old age, and severe coagulopathy at diagnosis [Degos et al. 1995; Sanz et al. 1988; Kantarjian et al. 1986]. However, even among patients who achieved CR with initial chemotherapy, 50-65% of these patients subsequently relapsed and only 30-50% of the patients remained alive at 2 years [Head et al. 1994; Fenaux and Degos, 1991; Rodeghiero et al. 1990; Cunningham et al. 1989].

The introduction of ATRA had prompted several study groups to explore the role of ATRA either as a single agent or in combination with chemotherapy. Although treatment with single-agent ATRA during induction results in CR rates of 72-90% [Tallman et al. 1997; Chen et al. 1991; Castaigne et al. 1990a, 1990b; Huang et al. 1988], the early mortality rate due to hemorrhagic complications and differentiation syndrome, often associated with a rapid rise in white blood cell (WBC) counts during the therapy with ATRA, remains high [Tallman et al. 2000, 1997; de Botton et al. 1998; Vahdat et al. 1994; Fenaux et al. 1993, 1992; Warrell et al. 1991]. Patients who achieve CR initially with ATRA alone generally relapse without additional chemotherapy. Therefore, subsequent trials focused on combining ATRA with chemotherapy to improve the clinical outcome. This combination results in extremely high antileukemic efficacy, leading to CR in 90-95% of patients with primary resistance reported in just a few anecdotal cases [Tallman and Altman, 2008].

The European APL (EAPL) group demonstrated that concurrent ATRA plus chemotherapy (3 + 7 daunorubicin and cytarabine) led to a better outcome than sequential ATRA followed by chemotherapy in terms of reduced relapse rate at 2 years (6% versus 16%) [Fenaux et al. 1999]. Although the CR (94% versus 95%) and mortality rates had not clearly improved with concurrent ATRA and chemotherapy, this approach has the benefit of possibly reducing the incidence of differentiation syndrome from approximately 25% with ATRA alone [Tallman et al. 2000; Vahdat et al. 1994] to approximately 10% with concurrent chemotherapy and ATRA [Sanz et al. 1999; Avvisati et al. 1996].

Therefore, the simultaneous administration of ATRA and anthracycline-based chemotherapy is currently considered the standard induction treatment in newly diagnosed patients with APL. With regards to the choice of anthracyclines, no prospective randomized trials have compared daunorubicin and idarubicin in APL. Although a retrospective analysis in a preliminary form has suggested that idarubicin is associated with an improved outcome compared with daunorubicin or amsacrine [Berman et al. 1991], there is no clear evidence that one anthracycline is clearly superior to another and both appear equally effective in APL.

The role of cytarabine in induction therapy

Unlike other forms of AML, anthracyclines have shown to be the most potent standard chemotherapeutic agents in APL [Avvisati et al. 1990], but the role of cytarabine in addition to ATRA and an anthracycline during induction remains a matter of investigation. The cooperative groups Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell'Adulto (GIMEMA) and the Programa Español de Tratamientos en Hematología (PETHEMA) have omitted cytarabine from the induction regimen, and demonstrated that ATRA combined with idarubicin alone (AIDA) is as effective in inducing remission with a cytarabinecontaining regimen with CR rates of 89-95% regardless of the presenting WBC counts [Sanz et al. 1999; Avvisati et al. 1996]. The Medical Research Council (MRC) in the United Kingdom similarly reported no differences in response, relapse or overall survival rates in patients randomized between AIDA and ATRA with daunorubicin and cytarabine, and observed less myelosuppression with the regimen omitting cytarabine. In contrast, a randomized study by the EAPL group (APL 2000) demonstrated a statistically significant increase in relapse risk (13.4 versus 29%) and decrease in overall survival (92.9 versus 83.3%) when cytarabine was omitted from both induction and consolidation therapy [Ades et al. 2006]. This discrepancy may be explained by the differences in the consolidation regimens (ATRA versus no ATRA in the EAPL trial), the specific choice of anthracycline (idarubicin in the GIMEMA, PETHEMA, and MRC trials versus daunorubicin in the EAPL trial), the number of consolidation courses, and the cumulative doses of anthracyclines.

The emerging nonchemotherapy, rationally targeted treatment

In the 1990s, significant benefits of ATO were reported in patients with relapsed and refractory APL [Soignet et al. 2001, 1998; Niu et al. 1999]. In these patients, ATO can induce CR in 50% of patients after a single 5-week course and in 86% of patients after two cycles [Soignet et al. 2001]. These trials have established ATO as the single most active agent in APL and have prompted studies investigating the role of ATO in previously untreated patients.

As a single agent, ATO can induce CR in 85-86% of patients with untreated APL, comparable with that achieved by ATRA-based therapy [Ghavamzadeh et al. 2006; Mathews et al. 2006]. The most benefit from single-agent ATO during induction and consolidation is observed in patients with the WBC counts of <5000/μl and platelet counts >20,000/μl at diagnosis with an event-free survival (EFS) of 100% at 3 years in a study by investigators in India [Mathews et al. 2006]. However, the outcome of patients with WBC >5000/μl at diagnosis appears to be inferior to a similar subset treated with ATRA plus chemotherapy, with an EFS of only 67% and a higher early death rate of 14.4% mostly from hemorrhagic complications [Mathews et al. 2006]. Therefore, therapy with single-agent ATO does not appear sufficient for many patients as a frontline therapy.

Combined use of ATRA and ATO has been shown to be synergistic in inducing differentiation and apoptosis in vitro and accelerating tumor regression in vivo, demonstrating a paradigm of rationally targeted therapy in leukemia [Zheng et al. 2005; Gianni et al. 1998]. Furthermore, an effective regimen lacking standard chemotherapeutic agents may potentially benefit patients unfit to receive intensive chemotherapy.

Investigators at the Shanghai Institute of Hematology conducted a randomized clinical trial in which patients were randomized to receive ATRA, ATO, or the combination of ATRA plus ATO as induction therapy [Shen et al. 2004]. Although all patients in CR after induction subsequently received consolidation and maintenance chemotherapy, potentially narrowing any differences in outcome among the three treatment arms, the combination treatment of ATRA and ATO achieved the lowest rate of relapse, a faster CR rate, and a greater reduction in the number of PML-RAR-α transcripts with no apparent greater toxicity than each agent alone. The updated report from this trial with a 7-year follow up confirms the high efficacy and minimal toxicity of the combination treatment for newly diagnosed APL, suggesting a potential frontline therapy for de novo APL [Hu et al. 2009].

Investigators at the MD Anderson Cancer Center similarly demonstrated that the combination treatment is an effective treatment in untreated APL, but only for low- and intermediate-risk patients [Estey et al. 2006]. In this patient population, an impressive CR rate of 96% was achieved, with few late relapses even when chemotherapy was eliminated during consolidation [Ravandi, 2010; Estey et al. 2006]. However, high-risk patients achieved an inferior CR rate of 79% despite the addition of gemtuzumab ozo-gamicin (GO) or idarubicin during induction to prevent hyperleukocytosis and the APL differentiation syndrome.

More recently, the Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group (ALLG) treated 124 patients with newly diagnosed APL with induction consisting of ATRA, ATO, and idarubicin. This was followed by two courses of consolidation with ATRA and ATO and 2 years of maintenance with ATRA, methotrexate, and mercaptopurine. With a median follow-up of 20 months, the 3-year overall survival (OS) and EFS rates were 93% and 87%, respectively. This strategy maintained a high long-term remission rate with significant reduction in exposure to standard chemotherapy [Iland et al. 2010].

These studies suggest that the combination of ATRA and ATO can effectively treat and potentially cure patients with low- and intermediaterisk disease, and has emerged as the most exciting new treatment strategy in APL as well as for patients who are considered unfit for conventional treatment and with severe comorbidities (e.g. patients with cardiac impairment or other severe organ dysfunction). However, concomitant use of cytotoxic drugs such as anthracyclines and cytarabine may be required, especially in patients presenting with high leukocyte counts, to prevent rapid development of leukocytosis and consequent APL differentiation syndrome. In rare cases where patients cannot tolerate anthracyclines due to severe cardiomyopathy and gemtuzumab ozogamicin is unavailable at treating institutions, cytarabine may be used as an alternative cytoreductive agent, although its efficacy without concomitant anthracyclines is unknown.

Strategies to reduce early death

Despite the dramatic impact of ATRA and ATO in the treatment of APL, deaths during induction from hemorrhage, infection, and differentiation syndrome continue to represent major causes for treatment failures in APL. Although multicenter cooperative studies report approximately 5 −10% early deaths within 1 month or initiation of treatment [Burnett et al. 2007; Fenaux et al. 1999; Sanz et al. 1999; Asou et al. 1998; Mandelli et al. 1997; Tallman et al. 1997; Avvisati et al. 1996], the true rate of early death in APL is likely to be higher [Micol et al. 2010; Park, 2010; Alizadeh et al. 2009; Derolf et al. 2009]. A large population-based study conducted in the United States examining the early death rates from 1992-2007 reported an early death rate of 17.3% despite ATRA, which is significantly higher than that reported in contemporary clinical trials [Park, 2010]. These findings identify previously unrecognized deficiencies in the treatment of APL and highlight the importance of raising clinical awareness of the rapid actions needed for diagnosis and aggressive supportive care to reduce the risk of early death. Therefore, it is important to consider the suspicion of APL as a medical emergency necessitating prompt initiation of ATRA and measures to counteract the coagulopathy at the very first suspicion of the diagnosis well before genetic confirmation.

Supportive measures to counteract coagulopathy consist of fresh frozen plasma, fibrinogen, cryo-precipitate and platelet transfusions to maintain the fibrinogen concentration and platelet count above 100-150 mg/dl and 50,000/μl, respectively, which should be monitored at least twice a day [Sanz et al. 2009; Tallman et al. 2005]. Such replacement therapy should continue during induction therapy until disappearance of all clinical and laboratory signs of coagulopathy.

In addition to aggressive blood product support, ATRA should be started immediately at the first suspicion of APL. ATRA has been shown to rapidly improve biochemical signs of APL coagulopathy, reduce the severity of bleeding, and decrease the amount of blood product consumption [Di Bona et al. 2000]. Although the real impact of ATRA in reducing the early death rate is unclear [Visani et al. 2000; Tallman et al. 1997], it is reasonable to presume a favorable risk-benefit ratio associated with this approach since ATRA is unlikely to have any deleterious effect should genetic assessment fail to confirm the diagnosis of APL. The role of ATO in reducing the early death rate is less clear, and more studies are required to better define the role of ATO with or without ATRA in reducing hemorrhagic complications during induction therapy [Hu et al. 2009; Estey et al. 2006; Shen et al. 2004].

Up to 50% of APL patients receiving ATRA during induction develop a reaction known as APL differentiation syndrome [Jurcic et al. 2007]. APL differentiation syndrome is characterized by fever, respiratory distress, radiographic pulmonary infiltrates, pleural or pericardial effusions, weight gain due to fluid overload, episodic hypotension, and acute renal failure. Although hyperleukocytosis is frequently associated with APL differentiation syndrome, the reaction may occur with a normal leukocyte count [Vahdat et al. 1994]. The cause of APL differentiation syndrome is unknown, although several mechanisms have been proposed, including the release of vasoactive cytokines, the expression of adhesion molecules on myeloid cell surfaces, and the ability of malignant promyelocytes to gain chemotactic properties as they undergo differentiation. The progression of APL differentiation syndrome can be terminated by early intervention with a short course of high-dose dexamethasone (10 mg twice a day for at least 3 days). Immediate recognition and appropriate intervention is imperative, since delayed treatment is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [Tallman et al. 2000; Frankel et al. 1992]. In uncontrolled trials, a very low mortality and morbidity rate was reported as a result of differentiation syndrome after ATRA treatment when corticosteroids were administered prophylactically in patients presenting with WBC counts >5000/μl [Sanz et al. 2004; Wiley and Firkin, 1995].

Lastly, since optimal treatment is dependent on rapid access to diagnosis and hospital facilities with ATRA and blood products, patients with APL should be treated at specialized centers. Breccia and colleagues reported a significantly increased early death rate in patients who initially presented to nonspecialized primary care institutions with little experience in the treatment of acute leukemia [Breccia et al. 2010]. Therefore, the immediate and efficient access to experienced medical centers to reduce the time span between the first signs and symptoms and initiation of specific therapy is essential to improve the clinical outcome. Recognizing the complexity in treatment of APL and the need for multidisciplinary treatment approach, an expert panel from the European LeukemiaNet recently published its guidelines suggesting that patients with APL to be treated at specialized centers with a multidisciplinary team serving a population of no fewer than 500,000 patients and with at least five patients being treated per year with intensive chemotherapy [Sanz et al. 2009].

Consolidation

Although treatment with ATRA results in greater than 90% CRs and the combination of ATRA and chemotherapy has improved the outcome of APL, patients will invariably relapse, providing a rationale for consolidation chemotherapy [Mandelli et al. 1997]. However, there is still no consensus on the optimal type and intensity of consolidation therapy, and much of the research effort has been focused on developing a risk-adapted treatment strategy to decrease the relapse rate in high-risk patients and reduce toxicity during consolidation therapy in low and intermediate risk and older patients. The consolidation approaches recently used by major cooperative studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Treatment schedule of recent acute promyelocytic leukemia cooperative group studies.

| Group | Number of Patients | WBC (×109/L) | Induction | Consolidation 1 | Consolidation 2 | Consolidation 3 | Consolidation 4 | Maintenance | Outcome (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PETHEMA/HOVON | 402 | ≤10 & Plts ≤40 | ATRA + IDA | ATRA + IDA | ATRA + MTZ | ATRA + IDA | ATRA + MP + MTX (2 years) | 3-yr CIR: 6 | |

| LPA 2005 | ≤10 & Plts >40 | ATRA + IDA | ATRA + IDA1 | ATRA + MTZ | AT RA + IDA1 | 3-yr DFS: 93 | |||

| 3-yr OS: 96 | |||||||||

| >10 | ATRA + IDA | ATRA + IDA + AraC | ATRA + MTZ2 | ATRA + IDA + AraC | 3-yr CIR: 6 | ||||

| GIMEMA | 453 | ≤10, Age ≤61 | ATRA + IDA | ATRA + IDA | ATRA+MTZ | ATRA + IDA | 3-yr DFS: 94 | ||

| AIDA 2000 | >10, Age ≤61 | ATRA + IDA | ATRA+ IDA + AraC | ATRA + VP16 + MTZ | ATRA + IDA + AraC + TG | 3-yr OS: 93 | |||

| 3-yr CIR: 11 | |||||||||

| 3-yr DFS: 82 | |||||||||

| 3-yr: OS: 79 | |||||||||

| ATRA + MP + MTX (2 year) | 6-yr CIR: 11 | ||||||||

| 6-yr DFS:86 | |||||||||

| 6-yr OS: 89 | |||||||||

| 6-yr CIR: 9 | |||||||||

| 6-yr DFS: 85 | |||||||||

| 6-yr OS: 83 | |||||||||

| FBS | 196 | <10, Age<60 | ATRA + DNR | DNR | DNR | 2-yr CIR: 16 | |||

| APL2000 | Randomized | ATRA + MP + MTX (2 years) | 2-yr EFS: 77 | ||||||

| ATRA + DNR + AraC | DNR + AraC | DNR + AraC | 2-yr OS: 90 | ||||||

| <10, Age>60 | ATRA + DNR | DNR | DNR | 2-yr CIR: 5 | |||||

| >10, Age<60 | ATRA + DNR + AraC | DNR + AraC | DNR + AraC | 2-yr EFS: 93 | |||||

| >10, Age>60 | ATRA + DNR + AraC | DNR + AraC | DNR + AraC | 2-yr OS: 98 | |||||

| 2-yr CIR: 9 | |||||||||

| 2-yr EFS: 79 | |||||||||

| 2-yr OS: 88 | |||||||||

| 2-yr CIR: 3 | |||||||||

| 2-yr EFS: 89 | |||||||||

| 2-yr OS: 92 | |||||||||

| 2-yr CIR: 6 | |||||||||

| 2-yr EFS: 78 | |||||||||

| 2-yr OS: 83 | |||||||||

| MRC | 291 | No stratification, Age <60 | ATRA + IDA | ATRA + IDA | ATRA + MTZ + /-GO | ATRA + IDA | ATRA + MP + MTX (1 year) | 4-yr OS: 85 | |

| AML15 | Randomized ATRA + DNR + AraC + VP 16 | ATRA + DNR + AraC+VP16 | Amsacrine + AraC + VP16+/-GO | IDA + MTZ + AraC | 4-yr OS: 81 | ||||

| North American Intergroup C9710 | 481 | No stratification | ATRA + DNR + AraC Randomized | ATRA + ATO | ATRA + ATO | ATRA + DNR | ATRA + DNR | ATRA + MP + MTX (1 year) | 3-yr DFS: 90 |

| 3-yr OS: 86 | |||||||||

| ATRA + DNR | ATRA + DNR | ATRA (1 year) | 3-yr DFS: 70 | ||||||

| 3-yr OS: 81 |

Abbreviations: APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; PETHEMA, Programa Espapol de Tratamientos en Hematologúa; HOVON, Hemato-Oncologie voor Volwassenen Nederland; Plts, platelets; ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid, IDA, idarubicin; MTZ, mitoxantrone; MP, mercaptopurine; MTX, methotrexate; CIR, cumulative incidence of relapse; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; AraC, cytarabine; GIMEMA, Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell'Adulto; VP16, etoposide; TG, thioguanine; FBS, French-Belgian-Swiss; DNR, daunorubicin; MRC, Medical Research Council; GO, gemtuzumab ozogamicin; ATO, arsenic trioxide; yr, year.

Denotes slightly reinforced idarubicin at 7 mg/m2 for 4 days (consolidation 1) and at 12 mg/m2 for 2 days (consolidation 3).

Denotes slightly reinforced mitoxantrone at 10 mg/m2 for 5 days.

The role of ATRA

Although the benefit of ATRA when combined with chemotherapy for consolidation has not yet been demonstrated in randomized studies, historical comparisons of consecutive trials by the GIMEMA [Lo-Coco et al. 2010] and PETHEMA [Sanz et al. 2004] groups showed a statistically significant reduction in the relapse rate (8.7 versus 20.1%) and a higher disease-free survival (DFS) and OS when ATRA was given in conjunction with chemotherapy. These reports suggest ATRA contributes to reduction of the relapse risk.

The role of cytarabine

In 2000, a joint meta-analysis of the PETHEMA and GIMEMA groups was carried out to identify relapse risk criteria in APL patients who had received an identical AIDA induction and a similar anthracycline-containing chemotherapy consolidation, and developed a predictive model to allow the distinction between low risk of relapse (WBC count <10,000/μl and platelet count >40,000/μl), intermediate risk (WBC count <10,000/μl and platelet count ≤40,000/μl) and high risk (WBC count ≥10,000/μl) [Sanz et al. 2000]. The resulting prognostic score has led to several risk-adapted trials in which consolidation varied according to the risk category.

Based on the benefit of cytarabine demonstrated in a joint study by the PETHEMA and the EAPL groups in high-risk patients [Sanz et al. 2000], the PETHEMA group conducted a study (LPA2005), in which high-risk patients received cytarabine combined with ATRA and idarubicin in the first and third consolidation courses (Table 1) [Sanz et al. 2010]. In this trial, they reported a favorable impact on the 3-year relapse rate (11% versus 26%, p = 0.03) when cytarabine was added to the consolidation in high-risk patients, although no differences in DFS and OS were observed.

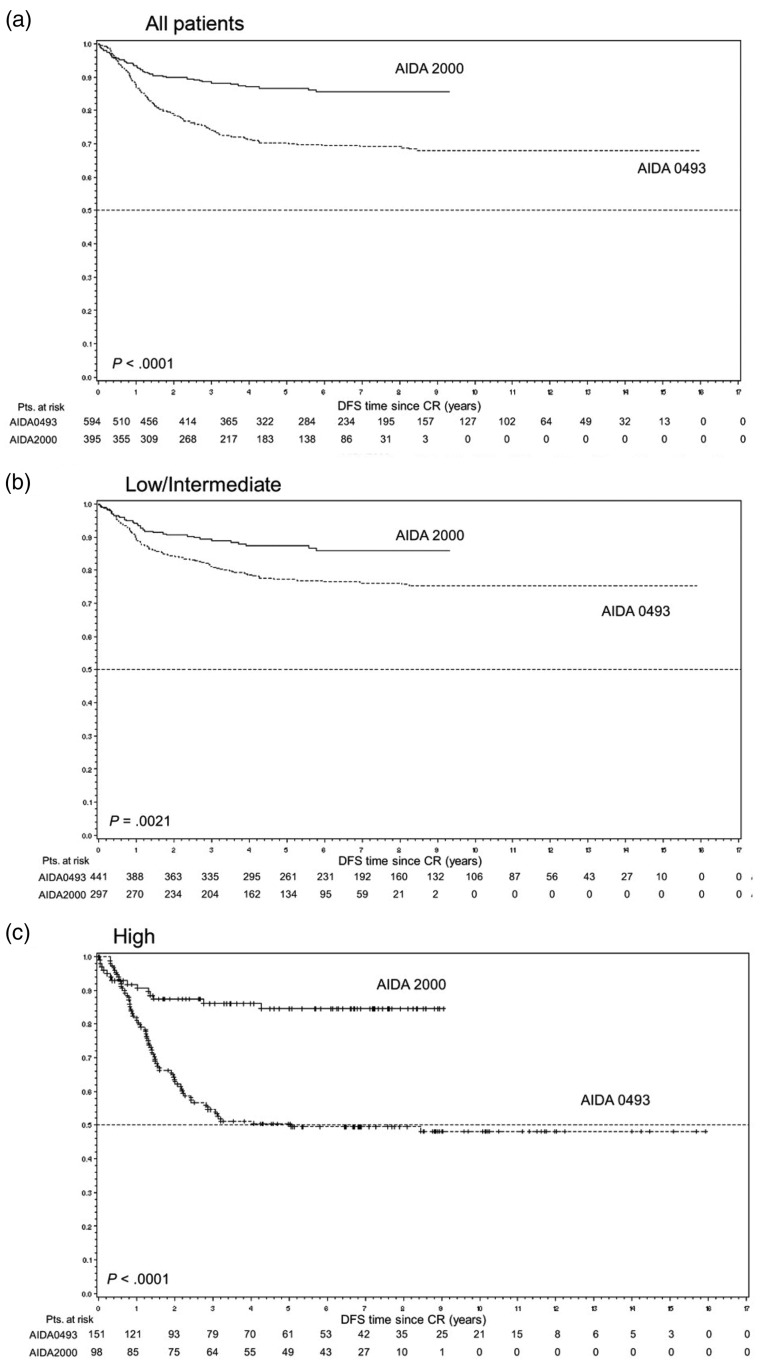

The GIMEMA group (AIDA2000) similarly reported a reduction of relapse rate (49.7 versus 9.3%) in high-risk patients when cytarabine was added to the consolidation (Figure 1) [Lo-Coco et al. 2010]. However, it should be noted that in the GIMEMA study, ATRA was also added to the consolidation therapy, which may have contributed to the improved outcome observed in the trial. In contrast, the study by the UK MRC group, published only in abstract form, showed no benefit of cytarabine, irrespective of risk category.

Figure 1.

Disease-free survival (DFS) according to protocol and risk groups (GIMEMA study) [Lo-Coco et al. 2010]: (A) all patients; (b) low-/intermediate-risk patients; (C) high-risk patients. In the AIDA 2000 protocol, postremission treatment was risk adapted. Patients with low/intermediate risk (B) received three anthracycline-based consolidation courses, whereas high-risk patients (C) received the same schedule as in the previous, non-risk-adapted AIDA-0493 trial including cytarabine. In addition, all patients in the AIDA 2000 trial received ATRA for 15 days during each consolidation [Powell et al. 2010]. Copyright 2010 Reproduced with permission of AMERICAN SOCIETY OF HEMATOLOGY (ASH).

Taken together, the majority of studies suggest a potential benefit of cytarabine in high-risk patients possibly due to the synergistic effect of the combination of ATRA plus cytarabine [Flanagan and Meckling, 2003], and that cytarabine could be avoided for low- and intermediate-risk patients, at least with high doses of idarubicin during induction and consolidation (cumulative doses of idarubicin and mitoxantrone of 80-100 mg/m2 and 50 mg/m2, respectively).

Nonchemotherapy consolidation regimen for low- and intermediate-risk patients

In order to reduce toxicity and chemotherapy exposure, several groups have investigated the role of ATO in consolidation as part of the firstline treatment. In a phase II study, Gore and colleagues substituted at least one cycle of cytotoxic chemotherapy with ATO, and reported a comparable outcome to previously reported trials using a risk-adapted approach [Gore et al. 2010]. The North American Intergroup addressed the role of ATO during consolidation in a randomized trial, in which patients received two courses of 25 days of ATO (5 days/week × 5 weeks) as a first consolidation followed by further consolidation with two courses of ATRA plus daunorubicin (Table 1) [Powell et al. 2010]. The results from the trial show that the addition of ATO as initial consolidation therapy significantly improves DFS and OS in patients of all risk groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Disease-free survival (A) and overall survival (OS) by treatment arm (North American Leukemia Intergroup Study) [Powell et al. 2010]. Copyright 2010 Reproduced with permission of AMERICAN SOCIETY OF HEMATOLOGY (ASH).

Investigators at the MD Anderson Cancer Center completely eliminated cytotoxic chemotherapy from consolidation and reported a comparable clinical outcome (3-year survival 85%) using ATRA and ATO for 28 weeks as the only postremission therapy but with a slightly worse outcome in high-risk patients [Ravandi et al. 2009]. The Indian APL Study Group (IAPLSG) treated patients in all risk groups with a single-agent ATO during induction and consolidation, and reported the clinical outcome comparable to that achieved with conventional combination chemotherapy in low- and intermediate-risk patients. However, for the high-risk patients, the relapse rate was higher (17% 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse) than with conventional therapy [Mathews et al. 2010].

In summary, the majority of studies suggest a potential synergism of an ATRA and ATO combination and raises the possibility of minimizing or even eliminating chemotherapy in patients with low- and intermediate-risk patients. Ongoing randomized trials comparing ATRA + ATO to ATRA + chemotherapy will hopefully answer the question of deintensifying APL therapy in this group of patients without compromising cure rates.

Maintenance

Despite two randomized trials demonstrating a substantial benefit provided by including an ATRA-based maintenance therapy, the systematic use of maintenance therapy is still controversial, particularly for low- and intermediate-risk patients and for patients achieving molecular remission at the end of consolidation. In fact, the maintenance therapy in the low- and intermediate-risk elderly patients may be harmful as shown by the EAPL group study that reported an 11% death rate in CR mainly from sepsis secondary to myelosuppression [Fenaux et al. 1999]. Furthermore, the introduction of ATO into first-line treatment for APL may reduce significance of maintenance therapy.

The North American Intergroup study first reported a clinical benefit with the ATRA-based maintenance therapy for a year in terms of a reduction in relapse rate (22% versus 39%) and a higher 5-year DFS (61% versus 36%) [Tallman et al. 2002; Tallman et al. 1997]. Similarly, the EAPL group confirmed the beneficial effect of adding ATRA to maintenance therapy in a randomized study with the regimen consisting of continuous low-dose 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate in addition to intermittent ATRA [Fenaux et al. 1999]. More importantly, the EAPL group recently updated the results of their previous study reporting for the first time that the clinical benefit of maintenance therapy was mainly observed in high-risk patients while only a marginal benefit was noted in patients with low- and intermediate-risk disease [Ades et al. 2010]. In contrast, two other randomized trials by the GIMEMA and Japanese Adult Leukemia Study Group (JALSG) have reported no benefit from maintenance therapy [Lo-Coco et al. 2010; Asou et al. 2007]. However, the JALSG group trial did not include ATRA as maintenance and the GIMEMA trial has been published only in abstract form.

The discrepancy in these studies suggests that the benefit of maintenance treatment may depend on prior induction and consolidation therapy, and PML-RAR-α status after consolidation therapy. For example, both the GIMEMA [Lo-Coco et al. 2010] and JALSG [Asou et al. 2007] groups administered three cycles of consolidation therapy and used idarubicin as anthracycline for induction and consolidation chemotherapy, whereas the EAPL [Fenaux et al. 1999] and North American Intergroup [Tallman et al. 1997] studies gave only two consolidation courses and used daunorubicin. Moreover, while studies by the GIMEMA and JALSG groups were carried out in patients testing negative for PML-RAR-α at the end of consolidation, the North American Intergroup and EAPL studies did not examine the molecular remission status at the end of consolidation, raising a question whether the benefit provided by the maintenance therapy is largely from patients with residual disease following consolidation.

These studies suggest that patients with low- and intermediate-risk APL and who achieve complete molecular remission after consolidation therapy may not benefit from the combination maintenance therapy.

For high-risk patients, maintenance therapy for 1 −2 years with intermittent ATRA and low-dose chemotherapy with 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate is recommended. Since there are no prospective trial data comparing 1 or 2 years of maintenance therapy, the current recommendation is to continue maintenance therapy for 2 years unless toxicity develops.

Following maintenance: Minimal residual disease monitoring

Detection of PML-RAR-α fusion transcripts using qualitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays in bone marrow samples at the end of consolidation or maintenance therapy has been shown to correlate with the relapse risk [Grimwade and Lo Coco, 2002; Lo Coco et al. 1999]. Several groups have conducted studies to investigate the role of minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring as a tool to direct pre-emptive therapy.

In the pre-ATO era, a prospective study by the PETHEMA group reported poorer survival in patients salvaged in frank relapse as compared with those treated in molecular relapse with comparable therapy [Esteve et al. 2007]. However, in the setting of highly effective salvage regimen with ATO, the role of MRD monitoring and optimal management for patients with documented molecular relapse remains uncertain [Breccia et al. 2004; Diverio et al. 1998].

A more recent prospective study by the UK MRC group has demonstrated that early treatment intervention with ATO on the basis of MRD monitoring prevented progression to overt relapse with a 3-year cumulative incidence of clinical relapse of 5%. In this study, however, the most benefit of sequential MRD monitoring was observed in high-risk patients. Therefore, at the present time, it seems reasonable to monitor patients with high-risk disease every 3 months from bone marrow samples or peripheral blood until 36 months postconsolidation as suggested by the study [Grimwade et al. 2009]. However, the role of sequential MRD monitoring in low- and intermediate-risk patients remains uncertain when the available therapy is so effective in inducing CR in these patients. Future studies are warranted to investigate whether the sequential MRD monitoring and MRD-directed therapy should be adopted as a standardized and cost-effective approach across the risk groups in APL.

Therapy at relapse

ATO is currently considered the best treatment option for patients who relapse. Several studies have demonstrated the high and sustained efficacy of ATO in patients with relapsed or refractory APL with CR rates of 80-90% and long-term survival of 50-70% at 1 −3 years [Shigeno et al. 2005; Au et al. 2003; Lazo et al. 2003; Raffoux et al. 2003; Niu et al. 1999]. The benefit of ATRA when added to ATO during induction in relapsed setting is not clear. Although a prospective randomized trial conducted by the investigators in France reported no benefit, it seems that some patients may have been resistant to ATRA [Raffoux et al. 2003].

Once patients attain the second CR (CR2), the options for consolidation include repeated cycles of ATO, standard chemotherapy in combination with ATRA and/or ATO, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Among these options, the best consolidation strategy is unknown. However, there is evidence to suggest improved outcome with treatment intensification with HSCT. Using autologous HSCT (auto-HSCT), a 70-80% 5-year DFS can be expected [Thirugnanam et al. 2009]. Allogeneic HSCT (allo-HSCT) involves a greater risk of treatment-related mortality (TRM) but offers a greater antileukemic activity due to the graft-versus-leukemia effect.

No formal guideline currently exists to help choose between auto- and allo-HSCT in relapsed APL as there have been no randomized controlled studies comparing the efficacy of auto-versus allo-HSCT. However, MRD monitoring can help inform decisions regarding transplantation in patients relapsing following frontline therapy. The GIMEMA group reported that patients with evidence of MRD who received a PCR-positive autograft invariably relapsed, whereas the majority of those transplanted in CR2 with a PCR-negative graft remained in remission [Meloni et al. 1997]. These data have recently been confirmed in a UK study that reported, in a preliminary form, 12 of 13 patients who underwent auto-HSCT in CR2 with a PCR-negative harvest remain in remission at a median of 2 years [Kishore et al. 2010]. The current best strategy appears to be auto-HSCT following ATO if molecularly negative cells can be harvested. However, patients with persistent detectable PML- RAR-α following ATO should proceed to allo-HSCT if a suitable HLA-matched donor is available.

The benefit of allo-HSCT in the relapsed setting has been demonstrated by several studies. A large survey by the European Cooperative Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation of 625 patients reported a lower risk of relapse with allo-HSCT but the outcome was similar between auto- and allo-HSCT groups due to higher TRM (24% in CR2) associated with allo-HSCT [Sanz et al. 2007]. In this series, a shorter time from diagnosis to transplant (<7.6 months in CR1 and < 18 months in CR2) was associated with higher relapse incidence in patients treated with auto-HSCT, and these patients may benefit more from allo-HSCT. Several other retrospective studies have reported a similar finding of lower relapse but higher TRM with allogeneic compared with autologous HSCT [Kohno et al. 2008; de Botton et al. 2005; Lo-Coco et al. 2003]. It should be noted that higher TRM in these studies were mainly observed in patients receiving very intensive chemotherapy regimens prior to allo-HSCT. With the advent of less-toxic and nonmyelosuppressive agent such as ATO, the outcome with allo-HSCT is likely to improve but will require further studies to confirm.

For patients who are unfit to proceed to HSCT, the available options include repeated cycles of ATO with or without ATRA or chemotherapy. Again, no clear guidelines exist to help choose between these options, but, in the U.S. muticenter study, four cycles of ATO as a single agent following induction and consolidation, 50% of patients were alive and free of recurrence at a median follow up of 17 months [Soignet et al. 2001].

Management of central nervous system relapse

The central nervous system (CNS) is the most common site of extramedullary relapse in APL and at least 10% of hematologic relapses are accompanied by CNS involvement [Evans and Grimwade, 1999]. The reported incidence of CNS relapses in APL ranges from 0.6% to 2% [Montesinos et al. 2009; de Botton et al. 2006; Specchia et al. 2001], and is invariably associated with marrow relapse and poor prognosis [de Botton et al. 2006]. CNS relapse has been shown to occur more frequently in patients with increased WBC count (>10 × 109/l), in younger patients (age <45 years), prior CNS hemorrhage, and in those with the bcr3 PML-RARα isoform, although only high WBC count appears to be the most consistent predictive factor [Montesinos et al. 2009; de Botton et al. 2006; Breccia et al. 2003]. However, there is a paucity of information in prevention and management of CNS relapse in patients with APL. Because the majority of CNS relapses occur in patients presenting with hyperleukocytosis, some strategies include CNS prophylaxis for patients in this particular high-risk setting, either in the form of high-dose cytarabine, ATO or intrathecal therapy (ITT) [Ades et al. 2006; Breccia et al. 2003]. The EAPL group recently reported a preliminary data demonstrating a trend toward lower incidence of CNS relapse when high-dose cytarabine was incorporated into consolidation therapy (0.4% versus 2.05%) but unclear role of intrathecal CNS prophylaxis, although numbers were too small to conclude [Ferini et al. 2010]. Another notable finding from the same study was an improved outcome of patients with CNS relapse compared with the historical control, which the authors attributed to the treatment of relapses with ATO [Ferini et al. 2010]. ATO has been demonstrated to penetrate the blood-brain barrier [Au et al. 2008], and may provide CNS prophylaxis to some extent when administered during first-line treatment. For patients without hyperleukocytosis, in whom the risk of CNS relapse is extremely low, there is a general consensus to avoid CNS prophylaxis. Currently, there is no standard CNS prophylactic therapy for high-risk patients, and prospective randomized studies comparing different regimens (high-dose cytarabine versus ATO versus ITT) will be required to formally answer the question. However, given the limited number of CNS events expected using these approaches, this type of trials will require large number of patients and may not be feasible.

Optimal management of APL patients with CNS relapse has not been critically assessed. In the absence of prospective or randomized trial data, it seems reasonable to adopt the treatment approach of CNS relapse in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and other subtypes of AML. In this regard, the expert panel from the European LeukemiaNet suggests induction treatment of CNS relapse consisting of weekly triple ITT with methotrexate, hydrocortisone, and cytarabine until complete clearance of blasts in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), followed by 6-10 more spaced out ITT treatments as consolidation [Sanz et al. 2009]. Because CNS disease is almost invariably accompanied by hematologic or molecular relapse in the marrow, systemic treatment should also be given. One approach could be to incorporate therapy with known CNS penetrance (e.g. high-dose cytarabine and ATO) while ITT is being delivered. In patients responding to treatment, allogeneic or autologous transplant should be the consolidation treatment of choice including appropriate craniospinal irradiation.

Genetic variants of APL

While the leukemia cells from vast majority of APL cases contain t(15;17)(q22;q11.12), several variant translocations involving RAR-α have been identified including t(11;17) and t(5;17). Distinguishing between these translocations is important because patients with some variants are almost invariably resistant to ATRA. However, specific management of the rare genetic variants of APL cannot be recommended because the available evidence is mostly based on single case reports. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to treat patients with ATRA-sensitive variants with standard protocols involving ATRA combined with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, while those with ATRA-resistant variants should be managed with AML-like approaches. Specifically, NuMA-RAR-α (NuMA, nuclear mitotic apparatus gene) from t(11;17)(q13;q21) translocation and NPM1-RAR-α from t(5;17)(q35;q21) translocation are known to be ATRA-sensitive, while STAT5b-RAR-α from der(17) and PLZF-RAR-α (PLZF, promyelocytic leukaemia zinc finger PLZF) from t(11;17)(q23;q21) are known to be ATRA-resistant [Arnould et al. 1999; Redner et al. 1996; Guidez et al. 1994].

Current and new clinical trials

Nonchemotherapy regimens in newly diagnosed APL

The Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) is leading a North American intergroup study, which is a phase II trial examining nonchemotherapy induction for high-risk patients using ATRA, ATO, and gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Table 2). Following induction, patients receive three courses of consolidation, first with ATO followed by ATRA and daunorubicin, and then by gemtuzumab.

Table 2.

Actively recruiting clinical trials for untreated acute promyelocytic leukemia.

| ClinicalTrials.gov study identification | Study Group | Study Design | Treatment Scheme | Trial Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT00408278 | PETHEMA | Risk-adapted therapy | Induction: ATRA + IDA | Spain |

| Consolidation: ATRA + IDA + MTZ +/- AraC per risk factors | ||||

| Maintenance: ATRA + MP + MTX | ||||

| NCT00482833 | GIMEMA | Phase III | Induction: ATRA + ATO versus ATRA + IDA | Italy |

| Consolidation: ATRA + ATO versus ATRA + IDA + MTZ | ||||

| Maintenance: ATRA + MP + MTX | ||||

| NCT00517712 | IAPLSG04 | Phase II/III | Induction: ATO | |

| Maintenance: ATO × 6 months versus 12 months | India | |||

| NCT00378365 | APL2006 | Phase III | Consolidation: ATO +/- ATRA versus anthracycline + AraC | France |

| NCT00551460 | SWOG | Phase II | Induction: ATRA + ATO + GO | US |

| Consolidation: ATO ×2 cycles → ATRA/DNR → GO | ||||

| Maintenance: ATRA + MP + MTX | ||||

| NCT00413166 | MD Anderson | Phase II | Induction: ATRA + ATO versus ATRA + ATO + GO + theophylline | US |

| Consolidation: ATRA + ATO versus ATRA+ATO + GO + theophylline | ||||

| Maintenance: ATRA + ATO |

Abbreviations: PETHEMA, Programa Español de Tratamientos en Hematología; ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid, IDA, idarubicin; MTZ, mitoxantrone; AraC, cytarabine; MP, mercaptopurine; MTX, methotrexate; GIMEMA, Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell'Adulto; ATO, arsenic trioxide; IAPLSG, Indian Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Study Group; APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; SWOG, Southwest Oncology Group; GO, gemtuzumab ozogamicin; US, United States.

In non-high-risk APL, the GIMEMA group is conducting a randomized trial investigating non-chemotherapy induction and consolidation treatments consisting of ATRA and ATO compared with anthracycline-based chemotherapy (AIDA).

Similar randomized studies have been initiated by the British National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI AML17 trial) and the investigators in France, which include all patients regardless of the presenting WBC counts. These trials will address the very important question of whether chemotherapy can be completely eliminated during induction and consolidation in APL by comparing the efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of ATRA and ATO regimen to the standard ATRA plus anthracycline chemotherapy approach.

In an attempt to further reduce the exposure to cytotoxic therapy, the IAPLSG is conducting a phase II/III study wherein patients will receive ATO as a primary induction therapy followed by either 6 or 12 months of ATO maintenance.

Novel agents for relapsed disease

Newer agents being studied in the setting of relapsed disease include a synthetic retinoid Tamibarotene [Di Veroli et al. 2010] and an oral retinoid analogue NRX 195183. Tamibarotene was developed to overcome ATRA resistance and is currently being studied in combination with ATO in patients with relapsed disease. NRX 195183 is being studied as a mono-therapy during induction and postremission for patients with relapsed APL (Table 3).

Table 3.

Actively recruiting clinical trials for relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia.

| ClinicalTrials.gov study identification | Study Group | Study Design | Treatment Scheme | Trial Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT00520208 | CytRx Corporation | Phase II | Tamibarotene for induction, consolidation, maintenance | US |

| NCT00985530 | Northwestern University | Phase I | Induction: ATO + tamibarotene | US |

| NCT00504764 | PETHEMA | Phase IV | Induction: ATO | Spain |

| Consolidation: ATRA + ATO → auto-HSCT versus allo-HSCT versus ATO + ATRA + GO | ||||

| NCT00196768 | German AML | Phase IV | Induction: ATO | Germany |

| Postremission: allo-HSCT versus auto-HSCT versus ATO/ATRA |

Abbreviations: US, United States; ATO, arsenic trioxide; PETHEMA, Programa Español de Tratamientos en Hematología; ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid; GO, gemtuzumab ozogamicin; auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Optimal consolidation following second CR

In order to address the question of optimal postremission therapy following the second induction therapy with ATO, the German AML group and the PETHEMA group will each conduct randomized studies to examine the role of allo-HSCT or auto-HSCT or ATO plus ATRA in patients in second CR (Table 3).

Future trials

Future prospective clinical trials are warranted to address the role of maintenance therapy in low- and intermediate-risk group patients, particularly when ATO is incorporated into induction and consolidation. The role of sequential MRD monitoring and MRD-directed therapy following successful first-line therapy remains unclear and requires further investigations. However, the design of a randomized study comparing pre-emptive versus delayed treatment would be ethically questionable because of the obvious advantage provided by pre-emptive treatment on counteracting early hemorrhagic mortality. In regards to prevention of coagulopathy related complications or reducing early death, although it will be difficult to address this question in clinical trial settings, early introduction of ATRA, very aggressive blood product support, and transfer to experienced medical centers will likely to have a major impact on reducing early deaths in APL.

Footnotes

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

References

- Ades L., Chevret S., Rafffoux E., de Botton S., Guerci A., Pigneux A., et al. (2006) Is cytarabine useful in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia? Results of a randomized trial from the European Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Group. J Clin Oncol 24: 5703–5710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ades L., Guerci A., Raffoux E., Sanz M., Chevallier P., Lapusan S., et al. (2010) Very long-term outcome of acute promyelocytic leukemia after treatment with all-trans retinoic acid and chemotherapy: The European APL Group experience. Blood 115: 1690–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh A.A., McClellan J.S., Gotlib J.R., Coutre S., Majeti R., Kohrt H.E., et al. (2009) Early mortality in acute promyelocytic leukemia may be higher than previously reported. Blood 114: 1015 [Google Scholar]

- Arnould C., Philippe C., Bourdon V., Gregoire M.J., Berger R., Jonveaux P. (1999) The signal transducer and activator of transcription STAT5b gene is a new partner of retinoic acid receptor alpha in acute promyelocytic-like leukaemia. Hum Mol Genet 8: 1741–1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asou N., Adachi K., Tamura J., Kanamaru A., Kageyama S., Hiraoka A., et al. (1998) Analysis of prognostic factors in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and chemotherapy. Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol 16: 78–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asou N., Kishimoto Y., Kiyoi H., Okada M., Kawai Y., Tsuzuki M., et al. (2007) A randomized study with or without intensified maintenance chemotherapy in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia who have become negative for PML-RARalpha transcript after consolidation therapy: The Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group (JALSG) APL97 study. Blood 110: 59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au W.Y., Lie A.K., Chim C.S., Liang R., Ma S.K., Chan C.H., et al. (2003) Arsenic trioxide in comparison with chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of relapsed acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Ann Oncol 14: 752–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au W.Y., Tam S., Fong B.M., Kwong Y.L. (2008) Determinants of cerebrospinal fluid arsenic concentration in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia on oral arsenic trioxide therapy. Blood 112: 3587–3590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avvisati G., Lo Coco F., Diverio D., Falda M., Ferrara F., Lazzarino M., et al. (1996) AIDA (all-trans retinoic acid + idarubicin) in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: A Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell'Adulto (GIMEMA) pilot study. Blood 88: 1390–1398 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avvisati G., Mandelli F., Petti M.C., Vegna M.L., Spadea A., Liso V., et al. (1990) Idarubicin (4-demethoxydaunorubicin) as single agent for remission induction of previously untreated acute promyelocytic leukemia: A pilot study of the Italian cooperative group GIMEMA. Eur J Haematol 44: 257–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J.M., Catovsky D., Daniel M.T., Flandrin G., Galton D.A., Gralnick H.R., et al. (1976) Proposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias. French-American-British (FAB) cooperative group. Br J Haematol 33: 451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J.M., Catovsky D., Daniel M.T., Flandrin G., Galton D.A., Gralnick H.R., et al. (1980) A variant form of hypergranular promyelocytic leukaemia (M3). Br J Haematol 44: 169–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman E., Little C., Kher U. (1991) Prognostic analysis of patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia [abstract]. Blood 78: 43a [Google Scholar]

- Breccia M., Carmosino I., Diverio D., De Santis S., De Propris M.S., Romano A., et al. (2003) Early detection of meningeal localization in acute promyelocytic leukaemia patients with high presenting leucocyte count. Br J Haematol 120: 266–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breccia M., Diverio D., Noguera N.I., Visani G., Santoro A., Locatelli F., et al. (2004) Clinico-biological features and outcome of acute promyelocytic leukemia patients with persistent polymerase chain reaction-detectable disease after the AIDA front-line induction and consolidation therapy. Haematologica 89: 29–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breccia M., Latagliata R., Cannella L., Minotti C., Meloni G., Lo-Coco F. (2010) Early hemorrhagic death before starting therapy in acute promyelocytic leukemia: Association with high WBC count, late diagnosis and delayed treatment initiation. Haematologica 95: 853–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett A.K., Hills R.K., Grimwade D., Goldstone A.H., Hunter A., Milligan D., et al. (2007) Idarubicin and ATRA is as effective as MRC chemotherapy in patients with acute promylocytic leukemia with lower toxicity and resource usage: Preliminary results of the MRC AML 15 trial. Blood 110: 181a [Google Scholar]

- Castaigne S., Chomienne C., Daniel M.T., Ballerini P., Berger R., Fenaux P., et al. (1990a) Alltrans retinoic acid as a differentiation therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia. I. Clinical results. Blood 76: 1704–1709 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaigne S., Chomienne C., Daniel M.T., Berger R., Miclea J.M., Ballerini P., et al. (1990b) Retinoic acids in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol 32: 36–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.X., Xue Y.Q., Zhang R., Tao R.F., Xia X.M., Li C., et al. (1991) A clinical and experimental study on all-trans retinoic acid-treated acute promyelocytic leukemia patients. Blood 78: 1413–1419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham I., Gee T.S., Reich L.M., Kempin S.J., Naval A.N., Clarkson B.D. (1989) Acute promyelocytic leukemia: Treatment results during a decade at Memorial Hospital. Blood 73: 1116–1122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Botton S., Dombret H., Sanz M., Miguel J.S., Caillot D., Zittoun R., et al. (1998) Incidence, clinical features, and outcome of all trans-retinoic acid syndrome in 413 cases of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. The European APL Group. Blood 92: 2712–2718 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Botton S., Fawaz A., Chevret S., Dombret H., Thomas X., Sanz M., et al. (2005) Autologous and allogeneic stem-cell transplantation as salvage treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia initially treated with all-trans-retinoic acid: A retrospective analysis of the European acute promyelocytic leukemia group. J Clin Oncol 23: 120–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Botton S., Sanz M.A., Chevret S., Dombret H., Martin G., Thomas X., et al. (2006) Extramedullary relapse in acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and chemotherapy. Leukemia 20: 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degos L., Dombret H., Chomienne C., Daniel M.T., Miclea J.M., Chastang C., et al. (1995) All-trans-retinoic acid as a differentiating agent in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 85: 2643–2653 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derolf A.R., Kristinsson S.Y., Andersson T.M., Landgren O., Dickman P.W., Bjorkholm M. (2009) Improved patient survival for acute myeloid leukemia: A population-based study of 9729 patients diagnosed in Sweden between 1973 and 2005. Blood 113: 3666–3672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bona E., Avvisati G., Castaman G., Luce M. Vegna, De Sanctis V., Rodeghiero F., et al. (2000) Early haemorrhagic morbidity and mortality during remission induction with or without all-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 108: 689–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Veroli A., Ramadan S.M., Divona M., Cudillo L., Gianni L., Wieland S., et al. (2010) Molecular remission in advanced acute promyelocytic leukaemia after treatment with the oral synthetic retinoid Tamibarotene. Br J Haematol 151: 99–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diverio D., Rossi V., Avvisati G., De Santis S., Pistilli A., Pane F., et al. (1998) Early detection of relapse by prospective reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analysis of the PML/RARalpha fusion gene in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia enrolled in the GIMEMA-AIEOP multicenter “AIDA” trial. GIMEMA-AIEOP Multicenter “AIDA” Trial. Blood 92: 784–789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteve J., Escoda L., Martin G., Rubio V., Diaz-Mediavilla J., Gonzalez M., et al. (2007) Outcome of patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia failing to front-line treatment with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline-based chemotherapy (PETHEMA protocols LPA96 and LPA99): Benefit of an early intervention. Leukemia 21: 446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estey E., Garcia-Manero G., Ferrajoli A., Faderl S., Verstovsek S., Jones D., et al. (2006) Use of all-trans retinoic acid plus arsenic trioxide as an alternative to chemotherapy in untreated acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 107: 3469–3473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans G.D., Grimwade D.J. (1999) Extramedullary disease in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 33: 219–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenaux P., Castaigne S., Dombret H., Archimbaud E., Duarte M., Morel P., et al. (1992) All-transretinoic acid followed by intensive chemotherapy gives a high complete remission rate and may prolong remissions in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: A pilot study on 26 cases. Blood 80: 2176–2181 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenaux P., Chastang C., Chevret S., Sanz M., Dombret H., Archimbaud E., et al. (1999) A randomized comparison of all transretinoic acid (ATRA) followed by chemotherapy and ATRA plus chemotherapy and the role of maintenance therapy in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. The European APL Group. Blood 94: 1192–1200 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenaux P., Degos L. (1991) Treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans retinoic acid. Leuk Res 15: 655–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenaux P., Le Deley M.C., Castaigne S., Archimbaud E., Chomienne C., Link H., et al. (1993) Effect of all transretinoic acid in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Results of a multicenter randomized trial. European APL 91 Group. Blood 82: 3241–3249 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferini G.A., Raffoux E., Guerci A., Pigneux A., Huguet F., Vey N., et al. (2010) Central Nervous System (CNS) at First Relapse In APL. A Report on 2 Multicenter Trials. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 116: 1084 [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan S.A., Meckling K.A. (2003) All- trans-retinoic acid increases cytotoxicity of 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine in NB4 cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 51: 363–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel S.R., Eardley A., Lauwers G., Weiss M., Warrell R.P., Jr (1992) The “retinoic acid syndrome” in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Ann Intern Med 117: 292–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavamzadeh A., Alimoghaddam K., Ghaffari S.H., Rostami S., Jahani M., Hosseini R., et al. (2006) Treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with arsenic trioxide without ATRA and/or chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 17: 131–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianni M., Koken M.H., Chelbi-Alix M.K., Benoit G., Lanotte M., Chen Z., et al. (1998) Combined arsenic and retinoic acid treatment enhances differentiation and apoptosis in arsenic-resistant NB4 cells. Blood 91: 4300–4310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore S.D., Gojo I., Sekeres M.A., Morris L., Devetten M., Jamieson K., et al. (2010) Single cycle of arsenic trioxide-based consolidation chemotherapy spares anthracycline exposure in the primary management of acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 28: 1047–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grignani F., Ferrucci P.F., Testa U., Talamo G., Fagioli M., Alcalay M., et al. (1993) The acute promyelocytic leukemia-specific PML-RAR alpha fusion protein inhibits differentiation and promotes survival of myeloid precursor cells. Cell 74: 423–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade D., Jovanovic J.V., Hills R.K., Nugent E.A., Patel Y., Flora R., et al. (2009) Prospective minimal residual disease monitoring to predict relapse of acute promyelocytic leukemia and to direct pre-emptive arsenic trioxide therapy. J Clin Oncol 27: 3650–3658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade D., Lo Coco F. (2002) Acute promyelocytic leukemia: A model for the role of molecular diagnosis and residual disease monitoring in directing treatment approach in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 16: 1959–1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidez F., Huang W., Tong J.H., Dubois C., Balitrand N., Waxman S., et al. (1994) Poor response to all-trans retinoic acid therapy in a t(11;17) PLZF/RAR alpha patient. Leukemia 8: 312–317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head D.R., Kopecky K.J., Willman C., Appelbaum F.R. (1994) Treatment outcome with chemotherapy in acute promyelocytic leukemia: The Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) experience. Leukemia 8(Suppl. 2): S38–S41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Liu Y.F., Wu C.F., Xu F., Shen Z.X., Zhu Y.M., et al. (2009) Long-term efficacy and safety of all-trans retinoic acid/arsenic trioxidebased therapy in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 3342–3347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M.E., Ye Y.C., Chen S.R., Chai J.R., Lu J.X., Zhoa L., et al. (1988) Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 72: 567–572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iland H., Firkin F., Supple S., Catalano A., Bashford J., Filshie R., et al. (2010) Interim analysis of the APML4 trial incorporating all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), idarubicin, and intravenous arsenic trioxide (ATO) as initial therapy in acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL): An Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group (ALLG) study. International Oral Arsenic Union & 38th Annual Scientific Meeting Hong Kong Society of Haematology, Vol. 16: Abstract 6, available at http://www.asianoncologysummit.com/aos2010/download/Iland%20AOS2010%20TLOCOSA.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jurcic J.G., Soignet S.L., Maslak A.P. (2007) Diagnosis and treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Curr Oncol Rep 9: 337–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian H.M., Keating M.J., Walters R.S., Estey E.H., McCredie K.B., Smith T.L., et al. (1986) Acute promyelocytic leukemia. M.D. Anderson Hospital experience. Am J Med 80: 789–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishore B., Stewart A., Jovanovic J., Craddock C., Grimwade D. (2010) Arsenic trioxide and stem cell transplantation is an effective salvage therapy in patients with relapsed APL. Br J Haematol 149(Suppl. 1): 2220151974 [Google Scholar]

- Kohno A., Morishita Y., Iida H., Yanada M., Uchida T., Hamaguchi M., et al. (2008) Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute promyelocytic leukemia in second or third complete remission: A retrospective analysis in the Nagoya Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group. Int J Hematol 87: 210–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazo G., Kantarjian H., Estey E., Thomas D., O'Brien S., Cortes J. (2003) Use of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the treatment of patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: The M. D. Anderson experience. Cancer 97: 2218–2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo-Coco F., Avvisati G., Vignetti M., Breccia M., Gallo E., Rambaldi A., et al. (2010) Front-line treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with AIDA induction followed by risk-adapted consolidation for adults younger than 61 years: Results of the AIDA-2000 trial of the GIMEMA Group. Blood 116: 3171–3179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo-Coco F., Romano A., Mengarelli A., Diverio D., Iori A.P., Moleti M.L., et al. (2003) Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for advanced acute promyelocytic leukemia: Results in patients treated in second molecular remission or with molecularly persistent disease. Leukemia 17: 1930–1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Coco F., Diverio D., Falini B., Biondi A., Nervi C., Pelicci P.G. (1999) Genetic diagnosis and molecular monitoring in the management of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 94: 12–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelli F., Diverio D., Avvisati G., Luciano A., Barbui T., Bernasconi C., et al. (1997) Molecular remission in PML/RAR alpha-positive acute promyelocytic leukemia by combined all-trans retinoic acid and idarubicin (AIDA) therapy. Gruppo Italiano-Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell'Adulto and Associazione Italiana di Ematologia ed Oncologia Pediatrica Cooperative Groups. Blood 90: 1014–1021 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews V., George B., Chendamarai E., Lakshmi K.M., Desire S., Balasubramanian P., et al. (2010) Single-agent arsenic trioxide in the treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: Long-term follow-up data. J Clin Oncol 28: 3866–3871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews V., George B., Lakshmi K.M., Viswabandya A., Bajel A., Balasubramanian P., et al. (2006) Single-agent arsenic trioxide in the treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: Durable remissions with minimal toxicity. Blood 107: 2627–2632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloni G., Diverio D., Vignetti M., Avvisati G., Capria S., Petti M.C., et al. (1997) Autologous bone marrow transplantation for acute promyelocytic leukemia in second remission: Prognostic relevance of pretransplant minimal residual disease assessment by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction of the PML/RAR alpha fusion gene. Blood 90: 1321–1325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micol J.-B., Raffoux E., Boissel N., Lengliné E., Canet E., Leblanc T., et al. (2010) Do early events excluding patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) from trial enrollment modify treatment result evaluation? Real-life management of 100 patients referred to the University Hospital Saint-Louis Between 2000 and 2010. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 116: Abstract 1083. [Google Scholar]

- Montesinos P., Diaz-Mediavilla J., Deben G., Prates V., Tormo M., Rubio V., et al. (2009) Central nervous system involvement at first relapse in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with alltrans retinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapy without intrathecal prophylaxis. Haematologica 94: 1242–1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu C., Yan H., Yu T., Sun H.P., Liu J.X., Li X.S., et al. (1999) Studies on treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with arsenic trioxide: Remission induction, follow-up, and molecular monitoring in 11 newly diagnosed and 47 relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia patients. Blood 94: 3315–3324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.H., Panageas K., Schymura M., Qiao B., Jurcic J.G., Rosenblat T., et al. (2010) A population-based study in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) suggests a higher early death rate and lower overall survival than commonly reported in clinical trials: Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program and the New York State Cancer Registry in the United States between 1992-2007 [Abstract]. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 116: Abstract 872. [Google Scholar]

- Powell B.L., Moser B., Stock W., Gallagher R.E., Willman C.L., Stone R.M., et al. (2010) Arsenic trioxide improves event-free and overall survival for adults with acute promyelocytic leukemia: North American Leukemia Intergroup Study C9710. Blood 116: 3751–3757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffoux E., Rousselot P., Poupon J., Daniel M.T., Cassinat B., Delarue R., et al. (2003) Combined treatment with arsenic trioxide and all-trans-retinoic acid in patients with relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 21: 2326–2334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravandi F., Estey E., Jones D., Faderl S., O'Brien S., Fiorentino J., et al. (2009) Effective treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans-retinoic acid, arsenic trioxide, and gemtuzumab ozogamicin. J Clin Oncol 27: 504–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravandi F., Estey E.H., Cortes J.E., O'Brien S., Pierce S.A., Brandt M., et al. (2010) Phase II study of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), arsenic trioxide (ATO), with or without gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) for the frontline therapy of patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 116: Abstract 1080. [Google Scholar]

- Redner R.L., Rush E.A., Faas S., Rudert W.A., Corey S.J. (1996) The t(5;17) variant of acute promyelocytic leukemia expresses a nucleophosmin-retinoic acid receptor fusion. Blood 87: 882–886 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodeghiero F., Avvisati G., Castaman G., Barbui T., Mandelli F. (1990) Early deaths and anti-hemorrhagic treatments in acute promyelocytic leukemia. A GIMEMA retrospective study in 268 consecutive patients. Blood 75: 2112–2117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley J.D., Golomb H.M., Dougherty C. (1977) 15/17 translocation, a consistent chromosomal change in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Lancet 1: 549–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M.A., Grimwade D., Tallman M.S., Lowenberg B., Fenaux P., Estey E.H., et al. (2009) Management of acute promyelocytic leukemia: Recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 113: 1875–1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M.A., Jarque I., Martin G., Lorenzo I., Martinez J., Rafecas J., et al. (1988) Acute promyelocytic leukemia. Therapy results and prognostic factors. Cancer 61: 7–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M.A., Labopin M., Gorin N.C., de la Rubia J., Arcese W., Meloni G., et al. (2007) Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for adults with acute promyelocytic leukemia in the ATRA era: A survey of the European Cooperative Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 39: 461–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M.A., Lo Coco F., Martin G., Avvisati G., Rayon C., Barbui T., et al. (2000) Definition of relapse risk and role of nonanthracycline drugs for consolidation in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: A joint study of the PETHEMA and GIMEMA cooperative groups. Blood 96: 1247–1253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M.A., Martin G., Gonzalez M., Leon A., Rayon C., Rivas C., et al. (2004) Risk-adapted treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-transretinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapy: A multicenter study by the PETHEMA group. Blood 103: 1237–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M.A., Martin G., Rayon C., Esteve J., Gonzalez M., Diaz-Mediavilla J., et al. (1999) A modified AIDA protocol with anthracycline-based consolidation results in high antileukemic efficacy and reduced toxicity in newly diagnosed PML/RARalpha-positive acute promyelocytic leukemia. PETHEMA group. Blood 94: 3015–3021 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M.A., Montesinos P., Rayon C., Holowiecka A., de la Serna J., Milone G., et al. (2010) Risk-adapted treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia based on all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline with addition of cytarabine in consolidation therapy for high-risk patients: Further improvements in treatment outcome. Blood 115: 5137–5146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z.X., Shi Z.Z., Fang J., Gu B.W., Li J.M., Zhu Y.M., et al. (2004) All-trans retinoic acid/As2O3 combination yields a high quality remission and survival in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 5328–5335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigeno K., Naito K., Sahara N., Kobayashi M., Nakamura S., Fujisawa S., et al. (2005) Arsenic trioxide therapy in relapsed or refractory Japanese patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: Updated outcomes of the phase II study and postremission therapies. Int J Hematol 82: 224–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soignet S.L., Frankel S.R., Douer D., Tallman M.S., Kantarjian H., Calleja E., et al. (2001) United States multicenter study of arsenic trioxide in relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 19: 3852–3860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soignet S.L., Maslak P., Wang Z.G., Jhanwar S., Calleja E., Dardashti L.J., et al. (1998) Complete remission after treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with arsenic trioxide. N Engl J Med 339: 1341–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specchia G., Lo Coco F., Vignetti M., Avvisati G., Fazi P., Albano F., et al. (2001) Extramedullary involvement at relapse in acute promyelocytic leukemia patients treated or not with all-trans retinoic acid: A report by the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell'Adulto. J Clin Oncol 19: 4023–4028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallman M.S., Altman J.K. (2008) Curative strategies in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 391–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallman M.S., Andersen J.W., Schiffer C.A., Appelbaum F.R., Feusner J.H., Ogden A., et al. (2000) Clinical description of 44 patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia who developed the retinoic acid syndrome. Blood 95: 90–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallman M.S., Andersen J.W., Schiffer C.A., Appelbaum F.R., Feusner J.H., Ogden A., et al. (1997) All-trans-retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 337: 1021–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallman M.S., Andersen J.W., Schiffer C.A., Appelbaum F.R., Feusner J.H., Woods W.G., et al. (2002) All-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia: Long-term outcome and prognostic factor analysis from the North American Intergroup protocol. Blood 100: 4298–4302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallman M.S., Brenner B., Serna L. Jde, Dombret H., Falanga A., Kwaan H.C., et al. (2005) Meeting report. Acute promyelocytic leukemia-associated coagulopathy, 21 January 2004, London, United Kingdom. Leuk Res 29: 347–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallman M.S., Kwaan H.C. (1992) Reassessing the hemostatic disorder associated with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 79: 543–553 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirugnanam R., George B., Chendamarai E., Lakshmi K.M., Balasubramanian P., Viswabandya A., et al. (2009) Comparison of clinical outcomes of patients with relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia induced with arsenic trioxide and consolidated with either an autologous stem cell transplant or an arsenic trioxide-based regimen. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 15: 1479–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahdat L., Maslak P., Miller W.H., Jr, Eardley A., Heller G., Scheinberg D.A., et al. (1994) Early mortality and the retinoic acid syndrome in acute promyelocytic leukemia: Impact of leukocytosis, low-dose chemotherapy, PMN/RAR-alpha isoform, and CD13 expression in patients treated with all-trans retinoic acid. Blood 84: 3843–3849 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visani G., Gugliotta L., Tosi P., Catani L., Vianelli N., Martinelli G., et al. (2000) All-trans retinoic acid significantly reduces the incidence of early hemorrhagic death during induction therapy of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Eur J Haematol 64: 139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrell R.P., Jr, Frankel S.R., Miller W.H., Jr, Scheinberg D.A., Itri L.M., Hittelman W.N., et al. (1991) Differentiation therapy of acute promyelocytic leukemia with tretinoin (all-trans-retinoic acid). N Engl J Med 324: 1385–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley J.S., Firkin F.C. (1995) Reduction of pulmonary toxicity by prednisolone prophylaxis during all-trans retinoic acid treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Australian Leukaemia Study Group. Leukemia 9: 774–778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P.Z., Wang K.K., Zhang Q.Y., Huang Q.H., Du Y.Z., Zhang Q.H., et al. (2005) Systems analysis of transcriptome and proteome in retinoic acid/arsenic trioxide-induced cell differentiation/apoptosis of promyelocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 7653–7658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]