Abstract

Background:

Fatigue is disabling and continuous phenomenon in cancer patients during and after various anticancer treatments which can continue for many years after treatment and definitely it has profound effect on Quality of Life (QOL). However, determining its severity is still underestimated among the cancer patients and also very few studies in the literature exist reporting on Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF) among Indian population.

Aims:

To find out the prevalence of rate of fatigue in cancer patient receiving various anti cancer therapies. To find out the relative impact of fatigue on QOL.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional observational study included a total 121 cancer patients receiving radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and concurrent chemo-radiation with the age group of above 15 years who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All the patients were assessed for severity of fatigue using Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) and for QOL using FACT-G scale while they were receiving the anticancer therapies as an in-patient in the regional cancer centers in Madhya Pradesh, India.

Results:

The severe fatigue was more prevalent in chemotherapy [58/59 (98.30%)], and concurrent chemo-radiation (33/42 (78.57%)) as compared to radiotherapy (Moderate-9/20 (45%) and Severe-9/20 (45%)). Moderate correlations were exhibited between fatigue due to radiotherapy and QOL (r = -0.71, P < 0.01), whereas weak correlation was found between fatigue due to chemotherapy and concurrent chemo-radiation (r = -0.361, P < 0.01 and r = -0.453, P < 0.01, respectively).

Conclusion:

Severity of fatigue was found more after chemotherapy and concurrent chemo-radiation therapy while impact on QOL was more after the radiotherapy.

Keywords: Anticancer therapy-related fatigue, Brief fatigue inventory, Cancer-related fatigue, Concurrent chemo-radiotherapy, FACT-G, Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF) is one of the most prevalent symptoms of patients with cancer[1–3] experience, both during and after treatment. It is prevalent condition among patients with cancer and survivors of cancer[1,4,5] that occur across all ages, genders, cancer diagnoses, stages of disease, and treatment regimens.[6] Fatigue associated with cancer or its treatment is distinct from the typical fatigue that most people experience as a result of normal daily life. Unlike typical fatigue, CRF is disproportionate to exertion level and is not relieved by rest or sleep.[7] Overall 50-90% of cancer patients experience fatigue the latter number corresponding with those undergoing active anticancer chemotherapy or radiotherapy.[1,3,4,8,9]

Fatigue can have an immensely negative impact on patients’ Quality of Life (QOL) and daily activities. Research reports that cancer-specific QOL is related to all stages of this disease.[10] The amount of symptoms distress experienced by an individual has been related to QOL in a number of people with cancer. QOL is increasingly being used as a primary outcome measure in studies to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment.[11]

Previous studies had clearly defined CRF as disabling and continuous phenomenon in patients during and after treatment[4] which can continue for many years after treatment and definitely it have profound effect on the life quality.[12] Until recently, fatigue in patients with cancer was under recognized and under-treated because attention has been focused on other common symptoms, such as nausea and pain.[13]

The pathogenesis of CRF is not well understood, and a variety of mechanisms may contribute to its development.[14] These involve effects of cancer or its treatment on the central nervous system, muscle energy metabolism, sleep, or circadian rhythms,[15] mediators of inflammation and stress,[16] immune activation,[17,18] and so on. CRF may occur due to various treatment therapies such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or concurrent chemo-radiation, which is one of the most common, ongoing symptom reported by the patient.[19,20] Fatigue is also common in patients undergoing radiation therapy[21] and in nearly all patients receiving the biologic modifiers interferon or interleukin-2.[22] Moreover, researchers estimated that about 70% of cancer patients experience fatigue during radiotherapy and chemotherapy.[23]

Severe fatigue leads not only to physical restrictions but also to serious impairment in QOL, social activities and the ability to go to work.[24,25] The incidence and severity of CRF appear to be influenced by characteristics of the patient,[26] primary malignancy, and type/intensity of treatment.[27] Therefore, CRF evaluation and classification should be the first step in the clinical assessment of cancer patients for the implementation of an appropriate treatment strategy. The diagnosis of CRF is usually achieved after the exclusion of reversible or treatable causes of fatigue,[22,28] and once these potential contributing factors are evaluated, the patients must be investigated through a brief and self-explanatory questionnaire such as Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) or Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI).[29,30]

Despite its high prevalence and potential negative effect on patients’ activities and emotional well-being, research in fatigue is still underdeveloped and there are only very few studies in the literature reporting on CRF among Indian population. Estimating the prevalence of CRF and its association with QOL will enable healthcare providers the adequate, accurate information regarding CRF. Also, it will help the physiotherapist to prescribe appropriate exercises and reduce the impact of fatigue, and improve QOL among cancer survivors.[7,31] Furthermore, till now the prevalence has been reported previously for either of two therapies combination or for single therapy and there are no studies in literature reporting the combined comparative prevalence of fatigue among all the three therapies. So the purpose of this study is to measure the proportion of fatigue among cancer patients receiving radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and concurrent chemo-radiotherapy and to assess its relative impact on QOL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

Cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and concurrent chemo-radiotherapy of this cross-sectional study were collected by adapting purposive sampling method from the SAIMS Medical College, Head and Oncology Centre, and from MY Government Hospital, Madhya Pradesh, India. Permission with the ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical committee of Srinivas College of Physiotherapy and Research Center and from the ethical committee of those hospitals. This study was approved by the ethical committee of Srinivas College of Physiotherapy and Research Center and was registered with Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, India.

A total 121 number of cancer subjects were selected for the study using purposive sampling. The sample consisted of patients receiving radiotherapy (20), chemotherapy (59), and concurrent chemo-radiation (42) who were included based on the following criteria. Patients with the age more than 15 years and with the Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) score at least 50 were included for the study. Any patient with known history of psychiatric disorders, neurological impairments, cognitive, and perceptual impairments were excluded from participation. The data was collected during the months of July, August, and November 2011.

MEASUREMENT TOOLS

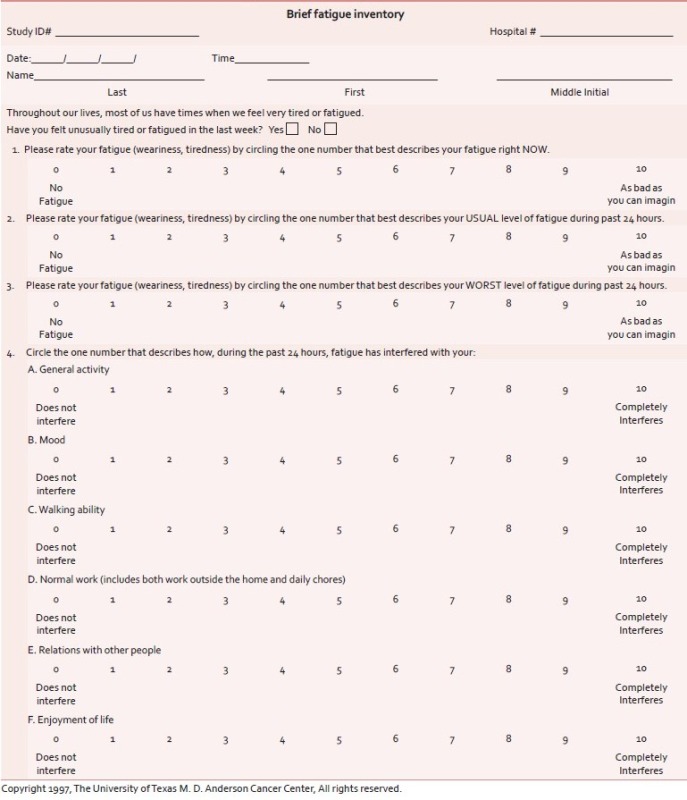

Brief fatigue inventory

The BFI[32] is used as screening tool for fatigue which measures severity of fatigue over the previous 24 hours (Alfa = 0.82 to 0.97). The BFI has only nine items, with the items measured on 0-10 numeric rating scales (Annexure 1). Three items ask patients to rate the severity of their fatigue at its “worst,” “usual,” and “now” during normal waking hours, with 0 being “no fatigue” and 10 being “fatigue as bad as you can imagine.” Six items assess the amount that fatigue has interfered with different aspects of the patient's life during the past 24 hours. The interference items include general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work (includes both work outside the home and housework), relations with other people, and enjoyment of life. The interference items are measured on a 0-10 scale, with 0 being “does not interfere” and 10 being “completely interferes. Fatigue was categorized using the BFI as either severe (score 7-10) or no severe (score 0-6), with the latter further subcategorized into moderate (score 4-6) and mild (score 0-3).[33]

The functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G) scale

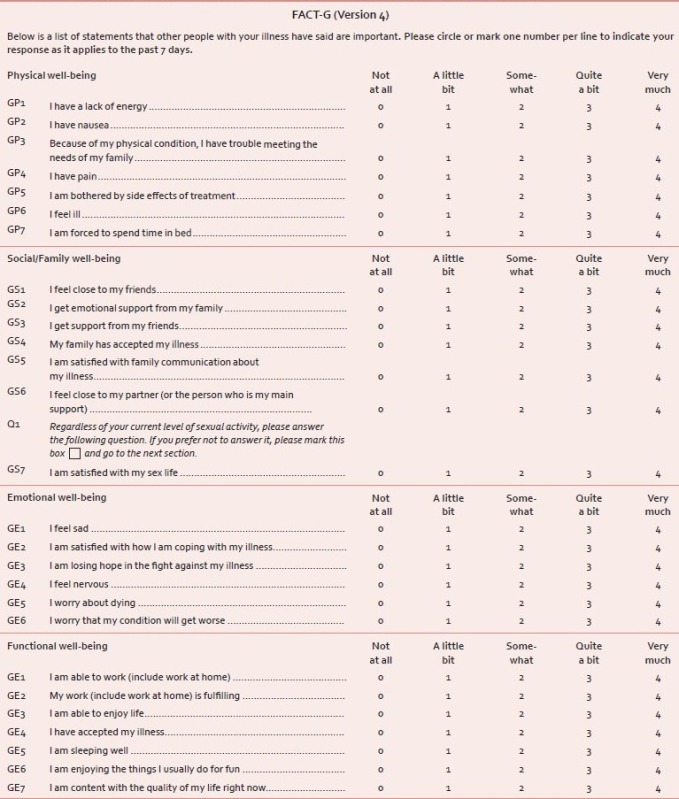

FACT-G[34] is widely used to measure health-related Quality Of Life (HRQOL) in cancer patients. The latest version 4 consists of a total of 27 Likert-type items formulated into separate subscales: Physical (seven items), emotional (six items), social/family (seven items), and functional (seven items) well-being (Annexure 2). Subjects are asked to respond to each item with a score of 0-4, where 0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = somewhat, 3 = quite a bit, and 4 = very much. A higher score indicates a better quality of life.[35]

Procedure

Participants who met the inclusion criteria were clearly explained about the study and written consent was taken from them stating their voluntary participation. Ethical committee approval was obtained from the hospitals where the patients were approached. Pre-participation data was taken for each subject prior to study which included name, age, sex, literacy level, concurrent disease, socioeconomic status, type of cancer, type of therapy received, and type of cancer. Along with this KPS score was also taken where, the lower the score, the worse the survival for most serious illnesses. The cut-off score was 50.

Survey was conducted in the months of July, August, and November 2011. Various types of cancer sufferers participated while they were receiving three different therapies in the hospital as in-patients. Subjects were asked to fill the questionnaire to measure their level of fatigue and quality of life by using Brief Fatigue Inventory and FACT-G respectively. The participants, who did not know to read and write, were explained about the questions in their mother tongue by the researcher and response was noted on the interview basis.

Statistical analysis

The data collected was tabulated using Microsoft Excel work sheet and the data was analyzed using SPSS 11.0 version. Prevalence rate is measured on the basis of number of patients under the category of mild, moderate and severe and their percentage is calculated from the total number of patient in each of three groups, i.e., radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and concurrent chemo-radiation using the descriptive statistics. Pearson product moment correlation was used to find out the association between the CRF and QOL in the all three groups.

RESULTS

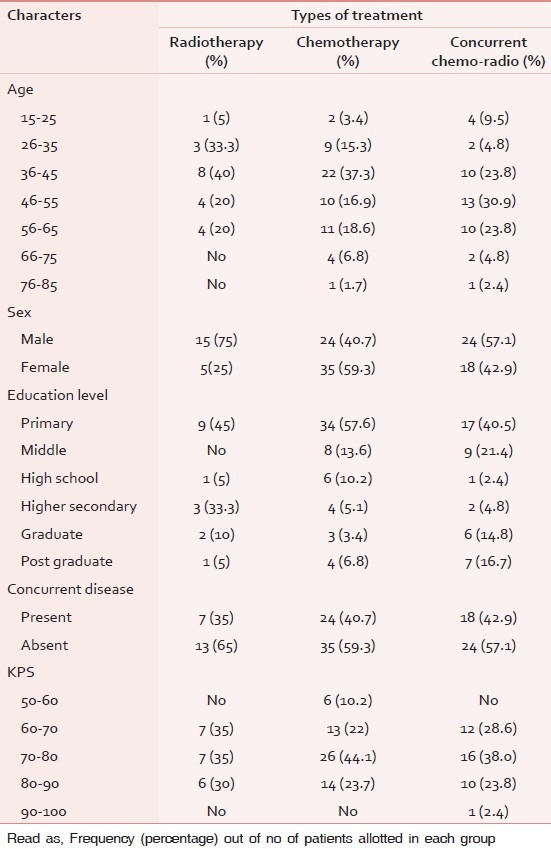

The details regarding KPS score, education, age group, concurrent disease, and sex ratio of various cancer patients receiving anticancer treatment is given in Table 1. Almost 95/121 subjects were between the age group of 35-65 years in this study and 60/121 patients only having primary school education. Among the 121 patients, 49 subjects were having one another concurrent diseases at that time. The detail of various type of cancer patients participated while they were receiving three different therapies is given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristic of the subjects

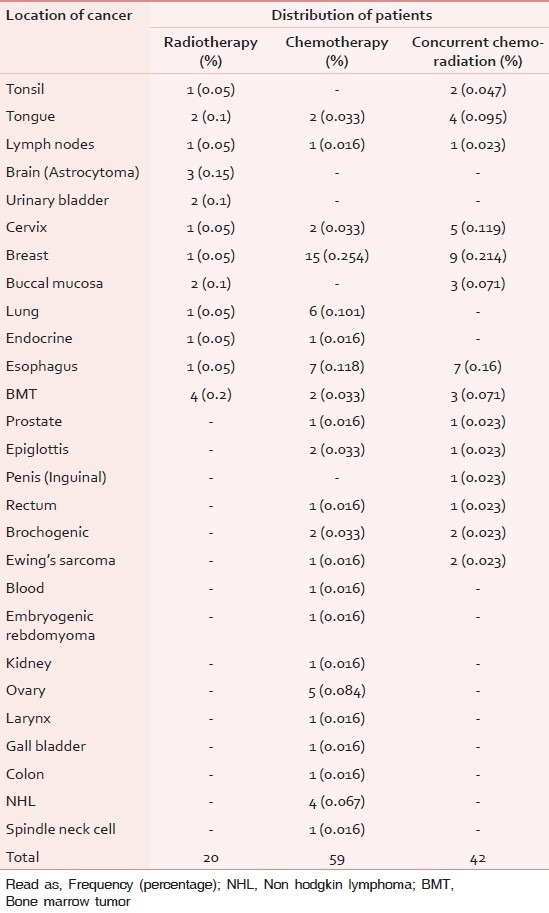

Table 2.

Number of patients based on cancer location in each treatment group

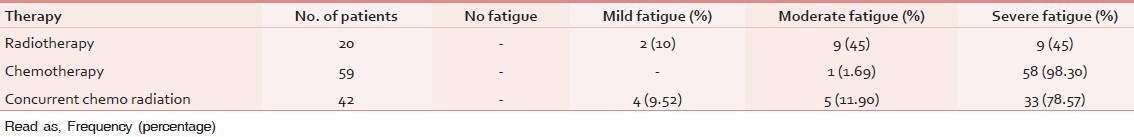

Table 3 describes the prevalence of fatigue (fatigue distribution) among the patients receiving the various therapies such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy and concurrent chemo-radiation. Out of 20 patients who received radiotherapy, 10% (2) reported mild fatigue, 45% (9) reported moderate, and 45% (9) reported severe fatigue. Among patients who received chemotherapy only 1 patient (1.69%) reported moderate fatigue, while rest all the patients (49) reported severe fatigue 98.30%. Among patients who received concurrent chemo-radiation, 4 patients reported (9.52%) mild fatigue and 5 patients reported moderate fatigue (11.90%) and 33 patients experienced severe fatigue (78.57%).

Table 3.

Fatigue distribution among different therapies

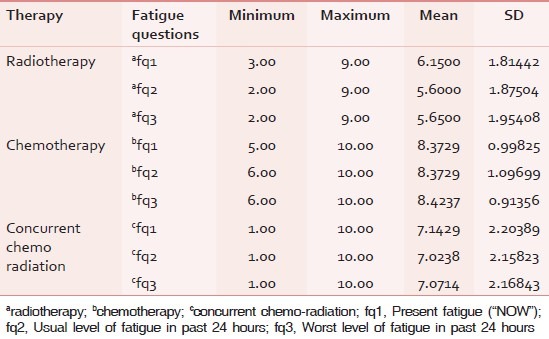

The mean and standard deviation for the level of present fatigue (fq1), usual level of fatigue in past 24 hours (fq2), and the worst level of fatigue in past 24 hours (fq3) in radiotherapy group were 6.15 ± 1.814, 5.6 ± 1.875, and 5.65 ± 1.954, respectively. The minimum and maximum values are given in Table 4. The mean and standard deviation for the level of present fatigue (fq1), usual level of fatigue in past 24 hours (fq2) and the worst level of fatigue in past 24 hours (fq3) in chemotherapy group were 8.37 ± 0.998, 8.37 ± 1.097, and 8.42 ± 0.914, respectively. The mean and standard deviation for the level of Present fatigue (fq1), usual level of fatigue in past 24 hours (fq2) and the worst level of fatigue in past 24 hours (fq3) in chemotherapy group were 7.14 ± 2.203, 7.02 ± 2.158, and 7.07 ± 2.168, respectively.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of the fatigue level in brief fatigue inventory for patients after different therapies

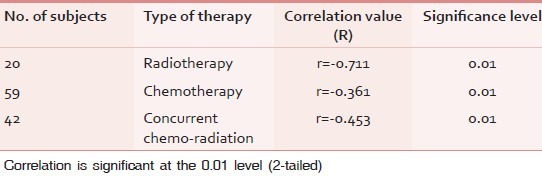

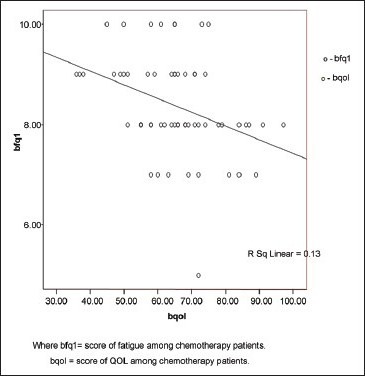

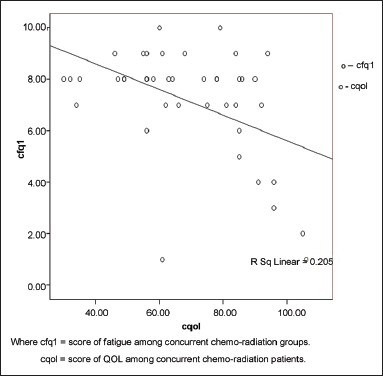

Correlation analysis of CRF and QOL reveals negative correlation. The correlation can be interpreted as any increase in severity of the level of fatigue, worst the QOL. The correlation was interpreted separately for fatigue occurring due to radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and concurrent chemo-radiation with quality of life domains. There is moderate correlation (r = –0.71 at 0.01 significance) between fatigue due to radiotherapy and QOL shown in Table 5 and Graph 1. Correlation between fatigue due to chemotherapy and QOL reveals weak correlation (r = –0.361 at 0.01 significance) shown in Graph 2. Correlation between fatigue due to concurrent chemo-radiation and QOL reveals negative and weak correlation (r = –0.453 at 0.01 significance) shown in Graph 3.

Table 5.

Correlation between fatigue and quality of life among three therapies

Graph 1.

Correlations between fatigue due to radiotherapy and quality of life

Graph 2.

Correlations between fatigue due to chemotherapy and quality of life

Graph 3.

Correlations between fatigue due to concurrent chemoradiation therapy and quality of life

DISCUSSION

CRF is the most prevalent phenomena in individuals with cancer who receive radiation therapy, cytotoxic chemotherapy, or biological response modifiers.[36] It is a multi-factorial, multidimensional phenomenon, which consists of physical, psychological, social, cognitive, and behavioral aspects.[37] Almost every patient suffers from fatigue during cancer treatment and in the scientific literature reported prevalence rates of fatigue are up to 99%.[8] In spite of growing evidence regarding the fatigue occurring due to various anticancer treatments and how CRF affect patient's quality of life, still determining its severity is underestimated among the cancer patients those who are suffering with this distressing symptom. The current study is focused on measuring the prevalence rate of fatigue (severity of fatigue) among the cancer patients receiving the various anticancer treatment, and how it impacts the QOL.

In our study, total 121 cancer subjects were selected. The type of cancer was already diagnosed with the help of histo-pathological reports, mammography, CT etc., FACT-G was used to measure HRQOL in our patients. Both the scales were applied while the patients were receiving the respective treatment regimen while admitted in the in-patient department.

CRF is present in majority of the patients at the start of the treatment.[20] Our results revealed that among 20 patients received radiotherapy, 10% had mild fatigue, and 45% patients perceived moderate and severe level of fatigue. Even other studies also found increased fatigue levels initially and then plateau of fatigue levels at Week 4 in a radiotherapy regimen that lasted 6 to 9 weeks.[38,39]

Radiotherapy causes transient increase in the fatigue which accumulates over weeks and reaches to the pretreatment level at one month after completion of treatment.[20] Pain can occur secondary to surgery or radiation therapy[40] and may lead to fatigue through its effects on mood, activity level, and/or sleep. Fatigue during radiotherapy is unique as the treatment is protracted over many weeks and the patient needs to travel all the way everyday to receive the treatment. Even in this study the patients were receiving for the duration of several weeks and the fatigue was measured between 14th and 15th session of radiotherapy treatment. It is also associated with significant acute radiation side effects which may alter the patient's nutrition, blood parameters leading to aggravation of the fatigue.[20] Furthermore, it was observed that the fatigue starts increasing from second week onwards and this coincides with the beginning of radiation reactions. This may explain the reason for lesser level of fatigue in this study as the fatigue measurement was taken only once, that too during early days while the patients were receiving the radiotherapy.

Fatigue is one of the most prevalent side effects during chemotherapy, usually persisting for more than two weeks; also, it has been shown to have the greatest and most long-lasting impact after chemotherapy.[2] It had been observed that during the first 24 to 48 hours of chemotherapy, there is a spiked rise in fatigue levels.[41,42] Fatigue level was measured here when the patients were receiving the second or third session of chemotherapy treatment. In this study, among 59 patients who were receiving chemotherapy, only one patient had moderate level of fatigue, while rest all patients experienced severe level of fatigue 98.30%. So the magnitude of fatigue after chemotherapy is more than that of radiotherapy treatment. A study by Donovan et al.[32] provides the first evidence that among women with early stage breast cancer, chemotherapy is associated with more severe fatigue than radiotherapy, which is similar to our results. They also found that women who received chemotherapy as their initial type of treatment for early stage breast cancer would report greater fatigue during the active treatment period than women who received radiotherapy as their initial treatment. In this study, the fatigue measurement was done only once that is while they were receiving the treatment and the population was not specific to one type of cancer, while Donovan et al. measured only in breast cancer patients. Still, 15 out of 59 patients in chemotherapy group were treated for breast cancer.

It was found that patients receiving a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy have reported higher levels of fatigue compared to those receiving a single therapy.[43,44] In patients receiving multiple forms of treatment for cancer, a “response shift” during the initial treatment may influence perceptions of fatigue during the second treatment, as patients become accustomed to their fatigue. Response shift is defined as a re-conceptualization of the quality of life brought about by a change in health status.[32] In this study, among the 42 patients receiving concurrent chemo-radiation in this study, 9.52% reported mild fatigue, 11.90% documented moderate level of fatigue, and 78.57% reported severe level of fatigue. So the magnitude of fatigue resulted after the concurrent chemo-radiation is more than that of radiotherapy alone and little lesser than that of chemotherapy alone in this study. This explains that patient felt more fatigued when they receive the chemotherapy than any other treatment.

Schmidt et al.[33] also found that fatigue level substantially increased during chemotherapy and radiotherapy and among the patients who received both therapies it was 61.4% higher, 30% same, and 8.6% lower fatigue level during chemotherapy. This study also documented that the severity of fatigue was more in patient receiving concurrent chemo-radiation and chemotherapy as compare to those who receiving the radiotherapy alone. Another study[32] also proved that even before the start of their initial treatment, women in the CT + RT group reported significantly more fatigue, both in terms of severity and disruptiveness, than women in the radiotherapy group.

That is, patients who received chemotherapy as their initial treatment were expected to report greater fatigue severity and disruptiveness than patients who received radiotherapy as their initial treatment. They also found that that fatigue increased during radiotherapy only among women not pre-treated with chemotherapy is consistent with research suggesting a response shift in perceptions of fatigue as a consequence of cancer treatment.[32] That means, reports of fatigue severity during subsequent radiotherapy may have been influenced by the perception that it was “not as bad” or “no greater” than the fatigue experienced during chemotherapy. At the same time, women not pre-treated with chemotherapy experienced increased fatigue over the course of radiotherapy, whereas women pre-treated with chemotherapy did not.[32] With respect to this result, previous findings[34] also found that fatigue would increase during radiotherapy only among patients who had not been treated previously with chemotherapy.

Two other studies reported higher levels of fatigue among former chemotherapy patients compared with those treated with radiation therapy alone.[35,45] By this at least one alternative explanation can be ruled out. The cause of CRF is not only the anticancer treatment, which is received by cancer patients; it is also reported before the initiation of treatment which is described by Goedendorp et al.[46] As per their statement, the reported factors that contributed to severe fatigue at this stage were physical activity, depressive mood, impaired sleep and rest, and fatigue 1 year before diagnosis. Meanwhile, another study found that the strongest fatigue predictor was poor mental health. In this study we have not considered any of these factors.

Fatigue was by far the predominant determinant of overall QOL, showing a univariate correlation with overall QOL of 0.76. As the previous studies had reported that CRF affects the QOL, correlation analyses of our study suggest that there is moderate correlation (r = –0.71 at 0.01 significance) between fatigue due to radiotherapy and QOL. At the same time, correlation between the fatigue due to chemotherapy and concurrent chemo-radiation and QOL reveals weak correlation (r = –0.361 at 0.01 significance, r = –0.453 at 0.001 significance, respectively). But the severity of fatigue was found more in concurrent chemo-radiation and chemotherapy group as compare to the radiotherapy group. Dagnelie et al.[47] found in their study that the fatigue showed by far the strongest univariate correlation with overall QOL (r = –0.76, P < 0.001).

Overall on observation, chemotherapy receiving patients had significantly more problems especially with smell aversion. Activity level inside and outside the home, anxiousness and depressive symptoms were similar in both groups. It is well argued that though there is significant strong correlation between CRF and QOL, this relationship could not be well established in our study due to number of samples in each group (as “r”value and P value sensitive to sample size). Janaki et al.[20] found the physical, role, cognitive and social functions were reduced during radiation therapy treatment and returns to baseline at one month follow up. Even, the length of time since diagnosis and treatment was associated with fatigue levels in only one study, which found a positive correlation between time since treatment and a one-item measure of fatigue.[48] We have not measured and correlated that factor also in this study as we took the fatigue evaluation only once. Moreover, this study has measured prevalence rate of fatigue among the Indian population for cancer patient receiving the radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and concurrent chemo-radiation, which is reported in only few literature.

Assessing fatigue will help the health care practitioner to diagnose and plan the treatment for reducing fatigue and helps the cancer patient improving their QOL. However, to understand the fatigue mechanism and to gain knowledge regarding the why severity of fatigue is more in chemotherapy and concurrent chemo-radiation longitudinal studies are required. In addition, CRF should be assessed before and after the initiation of anticancer treatments.

The finding of this study cannot fully justify the relationship between CRF due to various anticancer therapies and QOL. Though the previous studies have clearly documented that CRF have profound effect on quality of life, occurrence of CRF due to various anticancer treatment is not a single predictor for affecting QOL. There are many other variables which can affect QOL among cancer patients such as cancer type and stage, as some types of cancer do not present any symptoms until they are in advanced stages, time since diagnosis, patient acceptance, intensity of the disease, and the level of psychological distress experienced by caregivers.[49] These variables along with other confounders such as age, gender, tumor stage, and type of cancer should also be well documented and correlated with further upcoming studies, So that better treatment can be provided to improve patient QOL and reduced fatigue.

Though our study examined fatigue that is contributed by radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and combined chemo-radiation therapy, we have not assessed in specific cancer patients. Further studies should be conducted to assess the fatigue with respect to primary site, volume of irradiation, and other altered fractionation regimes. It becomes more imperative to study fatigue, and QOL by considering causative elements and co-morbid factors during various anti-cancer therapies as that is the standard care in most of the cancers. So, further research should be focused on specific type of cancer and cancer stages with respect to primary site. This might give better insight into the magnitude and management of fatigue in cancer patients undergoing more intensive treatment. In another aspect, because the type and duration of chemotherapy were not assessed in this report, it is unclear whether the intensity of chemotherapy received had any impact on fatigue levels. So it is possible that those who received more intensive chemotherapy regimens may have experienced more fatigue.

This study had certain other limitations in terms of sample size as it was relatively smaller and unequal between the groups. Nevertheless, the fact we did not examine potential correctable etiologies for patients’ fatigue is a limitation of this study. Whether our findings generalize to a more diverse population of women with any particular type or stage of cancer is not known. To precisely know fatigue distribution, how long its impact remains longitudinal, further studies should be done.

CONCLUSION

CRF occurs due to various anticancer therapies such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and concurrent chemo-radiation but the prevalence rate varies widely among all the therapies received by cancer patients. Severity of fatigue was more in chemotherapy and concurrent chemo-radiation group as compare to radiotherapy. CRF was found to be moderately correlated to QOL among the patients receiving radiotherapy and weakly correlated with chemotherapy and concurrent chemo-radiation groups. Therefore, assessment of CRF should begin once the patient diagnosed with cancer and before the patient began the anticancer treatment. Further, evaluating CRF before and after treatment will help healthcare practitioner in preventing and treating this severe distress symptom. Thus, it can be useful in clinical settings and for further research work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to acknowledge Dr.Vinod Bhandari (HOD, Oncology, SAIMS Medical College), Dr. Vandana (HOD, Head and Neck Oncology Department, RAU), and Dr. Tehsin, Dr.Abha Kaliya for their unswerving help and support during data collection. Furthermore, we are deeply indebted to Mr. Satpal Singh, who had helped in statistical analysis. In addition without fail, we gratefully acknowledge the Authority members, and clinical staff of SAIMS Medical College Indore, Head and Neck Oncology Center MAHU and MY Government Hospital Indore. Our thanks are expressed to all the participants of this study.

Annexure 1: Measurement of severity of fatigue using BFI

Annexure 2: Measurement of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) using FACT-G

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Curt GA, Breitbart W, Cella D, Groopman JE, Horning SJ, Itri LM, et al. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: New findings from the Fatigue Coalition. Oncologist. 2000;5:353–60. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curt G, Johnston PG. Cancer fatigue: The way forward. Oncologist. 2003;8:27–30. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-suppl_1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogelzang NJ, Breitbart W, Cella D, Curt GA, Groopman JE, Horning SJ, et al. Patient, caregiver, and oncologist perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: Results of a tripart assessment survey.The Fatigue Coalition. Semin Hematol. 1997;34:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fechner H, Bottomle A. Fatigue and quality of life: Lessons from the real world. Oncologist. 2003;8:5–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-suppl_1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langeveld NE, Grootenhuis MA, Voute PA, de Haan RJ, van den Bos C. No excess fatigue in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:204–14. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00629-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winningham ML. Strategies for managing cancer-related fatigue syndrome: A rehabilitation approach. Cancer. 2001;92:988–97. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4+<988::aid-cncr1411>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrow GR, Shelke AR, Roscoe JA, Hickok JT, Mustian K. Management of cancer-related fatigue. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:229–39. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200055960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stasi R, Abriani L, Beccaglia P, Terzoli E, Amadori S. Cancer-related fatigue: Evolving concepts in evaluation and treatment. Cancer. 2003;98:1786–801. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang XS, Giralt SA, Mendoza TR, Engstrom MC, Johnson BA, Peterson N, et al. Clinical factors associated with cancer-related fatigue in patients being treated for leukemia and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1319–28. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thatcher N, Hopwood P, Anderson H. Improving quality of life in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: Research experience with gemcitabine. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:S8–13. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:622–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein D, Bennett B, Friedlander M, Davenport T, Hickie I, Lloyd A. Fatigue states after cancer treatment occur both in association with, and independent of, mood disorder: A longitudinal study. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:240. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan JL, Carroll JK, Ryan EP, Mustian KM, Fiscella K, Morrow GR. Mechanism of cancer related fatigue. Oncologist. 2007;12:22–34. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutstein HB. The biologic basis of fatigue. Cancer. 2001;92:1678–83. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6+<1678::aid-cncr1496>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parker KP, Bliwise DL, Ribeiro M, Jain SR, Vena CI, Kohles-Baker MK, et al. Sleep/wake patterns of individuals with advanced cancer measured by ambulatory polysomnography. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2464–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cleeland CS, Bennett GJ, Dantzer R, Dougherty PM, Dunn AJ, Meyers CA, et al. Are the symptoms of cancer and cancer treatment due to a shared biologic mechanism? A cytokine-immunologic model of cancer symptoms. Cancer. 2003;97:2919–25. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collado-Hidalgo A, Bower JE, Ganz PA, Cole SW, Irwin MR, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2759–66. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott HR, McMillan DC, Forrest LM, Brown DJ, McArdle CS, Milroy R. The systemic inflammatory response, weight loss, performance status and survival in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:264–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bron D. Biological basis of cancer-related anaemia. In: Marty M, Pecorelli S, editors. Fatigue and Cancer. European School of Oncology Scientific Updates, 5. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2001. pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janaki MG, Kadam AR, Mukesh S, Nirmala S, Ponni A, Ramesh BS, et al. Magnitude of fatigue in cancer patients receiving radiotherapy and its short term effect on quality of life. J Cancer Res Ther. 2010;6:22–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.63566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jereczek-Fossa BA, Marsiglia HR, Orecchia R. Radiotherapy related fatigue. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;41:317–25. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malik UR, Makower DF, Wadler S. Interferon-mediated fatigue. Cancer. 2001;92:1664–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6+<1664::aid-cncr1494>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smets EM, Garssen B, Schuster-Uitterhoeve AL, De Haes JC. Fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 1993;68:220–4. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stasi R, Abriani L, Beccaglia P, Terzoli E, Amadori S. Cancer-related fatigue: Evolving Concepts in evaluation and treatment. Cancer. 2003;98:1786–801. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cosentino BW. Cancer Fatigue it's more than just being tired. EBSCO patient education reference. [Updated in 2007] [Last accessed on Jan 2012]. Available from: http://www.ebscohost.com/thistopic.php?marketID=16topicID=1034 .

- 26.Stone P, Richards M, Hardy J. Fatigue in patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1670–6. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cella D, Peterman A, Passik S, Jacobsen P, Breitbart W. Progress toward guidelines for the management of fatigue. Oncology (Williston Park) 1998;12:369–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Escalante CP, Kallen MA, Valdres RU, Morrow PK, Manzullo EF. Outcomes of a cancer-related fatigue clinic in a comprehensive cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mock V, Atkinson A, Barsevick AM, Berger AM, Cimprich B, Eisenberger MA, et al. Cancer-related fatigue.Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:1054–78. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan HG, Houédé-Tchen N, Yi QL, Chemerynsky I, Downie FP, Sabate K, et al. Fatigue, menopausal symptoms, and cognitive function in women after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: 1- and 2-year follow-up of a prospective controlled study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8025–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.6550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson T, Mock V. Exercise as an intervention for cancer-related fatigue. Phys Ther. 2004;84:736–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB, Andrykowski MA, Winters EM, Balducci L, Malik U, et al. Course of fatigue in women receiving chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy for early stage breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:373–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrykowski MA, Curran SL, Lighner R. Off-treatment fatigue in breast cancer surivors: A controlled comparison. J Behav Med. 1998;21:1–18. doi: 10.1023/a:1018700303959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt ME, Chang-Claude J, Vrieling A, Heinz J, Flesch-Janys D, Steindorf K. Fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: Temporal courses and long-term pattern. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:11–9. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mast ME. Correlates of fatigue in survivors of breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1998;21:136–42. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199804000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahlberg K, Ekman T, Gaston-Johansson F, Mock V. Assessment and Management of Cancer-related Fatigue in Adults. Lancet. 2003;362:640–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Servaes P, Verhagen S, Bleijenberg G. Determinants of Chronic Fatigue in Disease-free Breast Cancer Patients: A Cross-sectional Study. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:589–98. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenberg DB, Sawicka J, Eisenthal S, Ross D. Fatigue syndrome due to localized radiation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1992;7:38–45. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(92)90106-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geinitz H, Zimmerman FB, Stoll P, Thamm R, Kaffenberger W, Ansorg K, et al. Fatigue, serum cytokine levels, and blood cell counts during radiotherapy of patients with breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:691–8. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01657-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maunsell E, Brisson J, Deschenes L. Arm problems and psychological distress after surgery for breast cancer. Can J Surg. 1993;36:315–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kornblith AB, Herndon JE, 2nd, Weiss RB, Zhang C, Zuckerman EL, Rosenberg S, et al. Long-term adjustment of survivors of early stage breast carcinoma 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2003;98:679–89. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Bernaards C, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Fatigue in long-term breast carcinoma survivors: A longitudinal investigation. Cancer. 2006;106:751–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, Morrissey M, Johnson BA, Wendt JK, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: Use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer. 1999;85:1186–96. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1186::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The Functional Assessment Of Cancer Therapy Scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–79. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woo B, Dibble SL, Piper BF, Keating SB, Weiss MC. Differences in fatigue by treatment methods in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:915–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goedendorp MM, Gielissen MF, Verhagen CA, Peters ME, Bleijenberg G. Severe fatigue and related factors in cancer patients before the initiation of treatment. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1408–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dagnelie PC, Pijls-Johannesma MC, Lambin P, Beijer S, de Ruysscher D, Kempen GI. Impact of fatigue on overall quality of life in lung and breast cancer patients selected for high-dose radiotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:940–4. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berglund G, Bolund C, Fornander T, Rutqvist LE, Sjödén PO. Late effects of adjuvant chemotherapy and postoperative radiotherapy on quality of life among breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27:1075–81. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90295-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heydarnejad MS, Hassanpour DA, Solati DK. Factors affecting quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11:266–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]