Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study is to understand the social determinants of quality of elderly life in rural central India and describe their perspectives on various issues related to their quality of life.

Materials and Methods:

It was a community-based mixed-methods study in which quantitative (survey) method was followed by qualitative (Focus Group Discussion, FGD). The study was done in field practice area of a Rural Health Training Centre. We decided to interview all the elderly (>60 years) in two feasibly selected wards of village Anji by using the “WHO-Quality of Life (WHOQOL)-brief questionnaire.” We used WHOQOL syntax for the calculation of mean values of four domains. Following survey, four FGDs were carried out.

Results:

The determinants of perceived physical health, amenable for intervention were their currently working status, not being neglected by the family, and involvement in social activities. The determinants for psychological support were health insurance, and their current working status. The determinants for social relations were membership in social group and their present working status. The determinants for perceived environment were membership in social groups and relationship with the family members. In qualitative research, factors such as active life, social activity, spirituality, health care, involvement in decision making, and welfare schemes by the Government were found to contribute to better quality of elderly life. Problems or conflicts in family environment, lack of shelter and financial security, overtapped resources, and gender bias add to negative feelings in old age life.

Conclusions:

There is a need for intervention at social and family level for elderly friendly environment at home and community level.

Keywords: Old age, Quality of life, Social determinants

INTRODUCTION

In India, proportion of elderly (above 60 years) has shown an increase from 5.6% in 1961 to 7.5% in 2011.[1] Majority of elderly in India lives and work in the unorganized agricultural sector in rural area. The poor understanding of elderly life under changing economic and social norms in India has led to a weak care and support for them.[2] In India, where recently initiated National Program for Health Care of Elderly (NPHCE) aims to develop infrastructure and built capacity of health care providers for elderly health care, around the world, there is growing concern to achieve sustainable quality of life. The concept of “active aging” has also fostered interest in the well-being and life satisfaction dimension; however, the definition of quality of elderly life and its determinants remained a concern.[3] Hence, the present pilot study was undertaken to understand the social determinants of quality of elderly life in rural central India and describe the perspectives of elderly on various issues related to their quality of life.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present community-based mixed-methods study in which the quantitative (survey) method was followed by the qualitative (Focus Group Discussion, FGD)[4,5] method was done at Kasturba Rural Health Training Centre, Anji, which is a Rural Health Training Centre of Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences (MGIMS), Sewagram. It is located in the rural Vidharba region of Maharashtra state.

Quantitative survey

We decided to interview all the elderly (>60 years) in two feasibly selected wards of village Anji. “WHO-Quality of Life-brief questionnaire” (English version) was used for the assessment of perceived quality of life.[6] We had the English version of WHOQOL tool which we had translated in Marathi and back-translated in English to ensure that the meaning of the questions are not altered and the Marathi translation was used in the field. We had taken permission from the World Health Organization to use this questionnaire for the present research work. The questionnaire is developed by the WHOQOL Group with 15 international field centers, in which India was one of the centers. WHOQOL-brief allows detailed assessment of four domains of quality of life-physical health, psychological support, social relationships, and environment. After obtaining the informed consent, the questionnaire was administered by a team of trained medical interns and medical doctors by paying house-to-house visits. All interviewers were well versed with local language Marathi and English. Socio-demographic characteristics such age, sex, education, marital status, and socio-economic status were collected. Apart from this, information on respondent's perceived relationship with the family members and their involvement in decision making was also collected. The current health insurance status of the respondents was assessed under the indoor insurance scheme run by MGIMS, Sewagram.[7] The study period was from December 2009 to January 2010.

The data were entered and analyzed by using Statistical Package for Social Sciences 12.0.1 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). We used WHOQOL syntax for the calculation of mean values of four domains. The mean scores for “perceived” quality of life for domains such as physical health, psychological health, social relations, and control of environments were calculated. High mean values signified better quality of life. First, the association of individual variables with each of the quality of life measures was assessed by bi-variate correlation coefficients. At second stage, multiple regression analysis was used to identify the combinations of variables that best predict the quality of life for four domains of quality of life. All 13 potential predictors were entered into the model using the enter selection method. The multiple coefficient of determination (R2) was used as the goodness-of-fit statistic for the model: It represents the proportion of variance in the outcome variable that can be accounted for by the predictors in the model. Statistical significance was set at 5% (P < 0.05) in the two-tailed test.

Qualitative assessment

Four Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), two each with 8-12 elderly men and women who were willing to participate, were undertaken in study area. It was moderated by a team of trained male social worker (Masters in Social Work) and female medical officer having 2 years of work experience in the study area. Both the moderators were well versed in local language Marathi. FGDs were conducted at the time and place convenient to the participants. Moderators used semi-structured guidelines which were based on old age policy document. Discussions were audio-taped and transcribed as verbatim. The transcripts were analyzed using Atlas-ti software, version WIN 5.0. Two trained medical officers independently carried out structural coding in all the transcripts using the borrowed code list from the existing literature, WHOQOL-brief questionnaire, and policy document.[8] Structural coding was applied to content based on or phrases representing a topic of inquiry to a segment of data that relied to a specific research question used to frame the interview.[9] These structural codes were active life, social life, spirituality, health care, welfare, financial security, shelter, nutrition, relationships, problems faced, negative feelings, gender bias, and attitude toward death. A trained faculty in Community Medicine (first author) who has more than 5 years of experience in doing qualitative research carried out a manual exercise to find out Holsti's CR inter-coder reliability for each codes.[10] Since, it was an exploratory study, the inter-coder reliability of 0.60 or more was considered appropriate. The disagreements in coding were resolved by discussion between the coders. The final text report and a conceptual framework were prepared from the summary of coded text and it was representative of our collective understanding of text data. Statements in Italics indicate direct quotations from the respondent and statements in square brackets indicate statements/reflections by the authors. The analysis and interpretation was undertaken over a long period of 6 months time. Informed consent was obtained from each participant 1 day prior to the FGD session and before audio-taping the discussion. Refreshments were served to the participants after each FGD session was over. We have followed proposed “Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research” (COREQ) guidelines while reporting the present qualitative work.[11]

RESULTS

Results of survey findings

Study subjects

Out of 180 enlisted elderly in two wards of village Anji, we could cover 142 (78.8%) by paying house-to-house visit. The median age of the respondents was 65 years. Out of 142 responding elderly, 78 (54.9%) were males and 65 (45.1%) were females. Among these, 88 (61.9%) were illiterate and 54 (38.1%) could read and write. Seventy-four elderly (52.1%) were below poverty line. Only 51 (35.9%) were health insured and 38 (26.7%) were members in the social group such as the self-help group. Majority i.e. 111 (78.2%) were married and 70 (49.3%) were presently working for their livelihood.

Perceived physical health

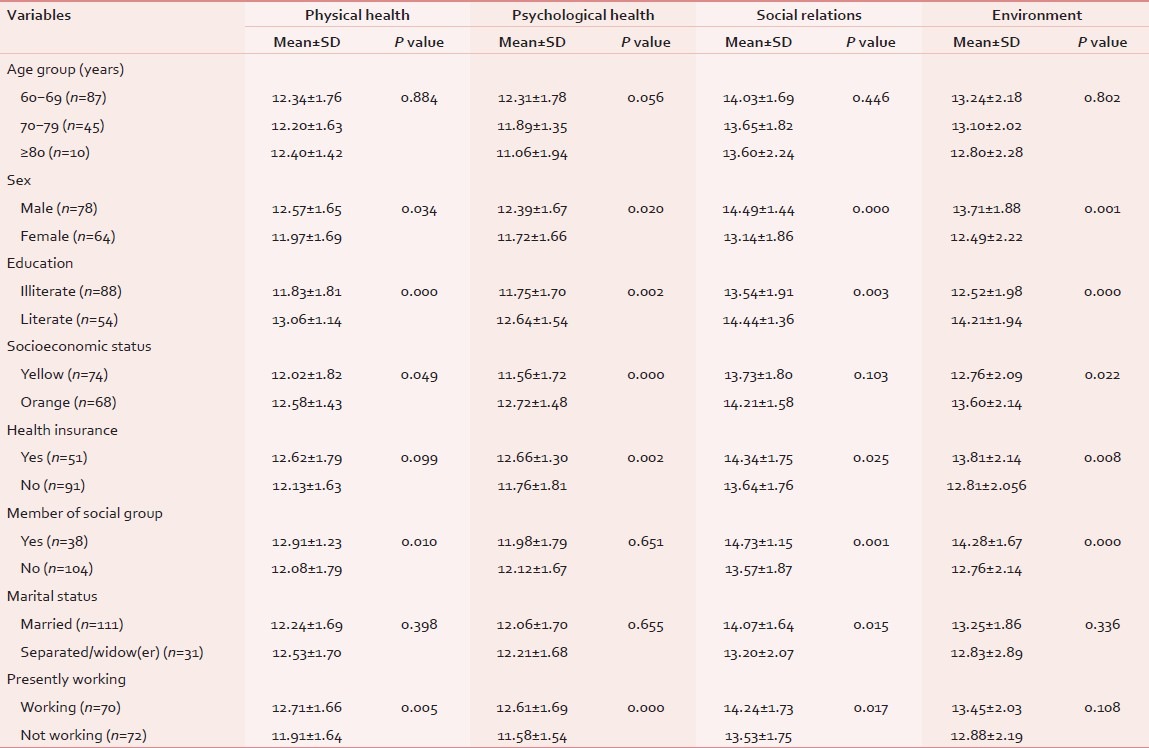

The differences in mean scores did not differ significantly across different age groups. The mean score among men (12.57) was significantly higher than in women (11.97). Similarly, the mean scores were significantly higher among literate (13.06) than among illiterate (11.83), elderly who were above poverty level (12.58) than those who were below poverty level (12.02), among those who were members of social group (12.91) than those who were not (12.08), and those who were currently working (12.71) than those who were not (11.91). It did not differ significantly across marital and health insurance status [Table 1].

Table 1.

Domains of quality of life by individual and family characteristics

The elderly who were involved in the decision making in the family perceived their physical health significantly better than those who were not (mean scores: 12.56 and 11.50, respectively). Similarly, those who were involved in social life and were economically independent perceived their physical health significantly better than those who were not involved in social life and were not economically independent. No significant association was found with relations with family members and the neglect by family [Table 2].

Table 2.

Domains of quality of life by the perceived characteristics

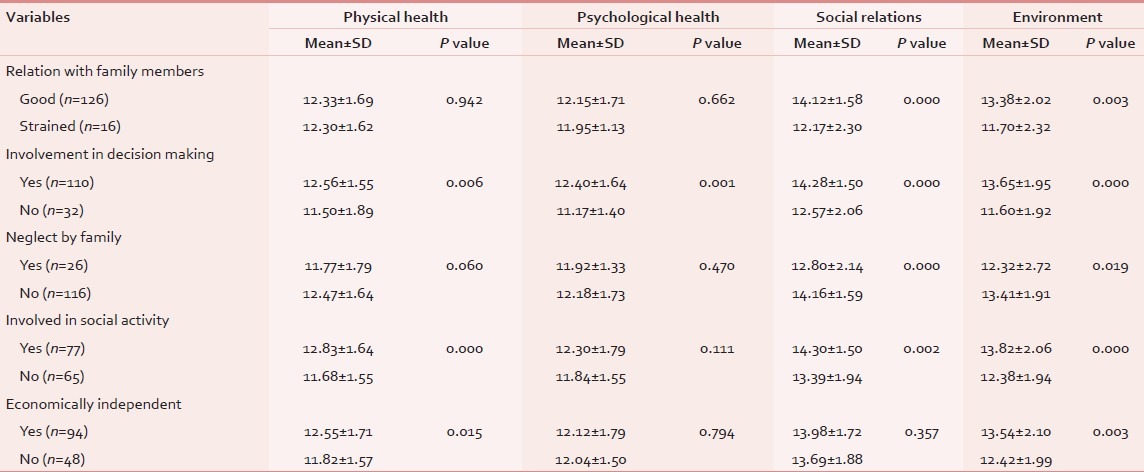

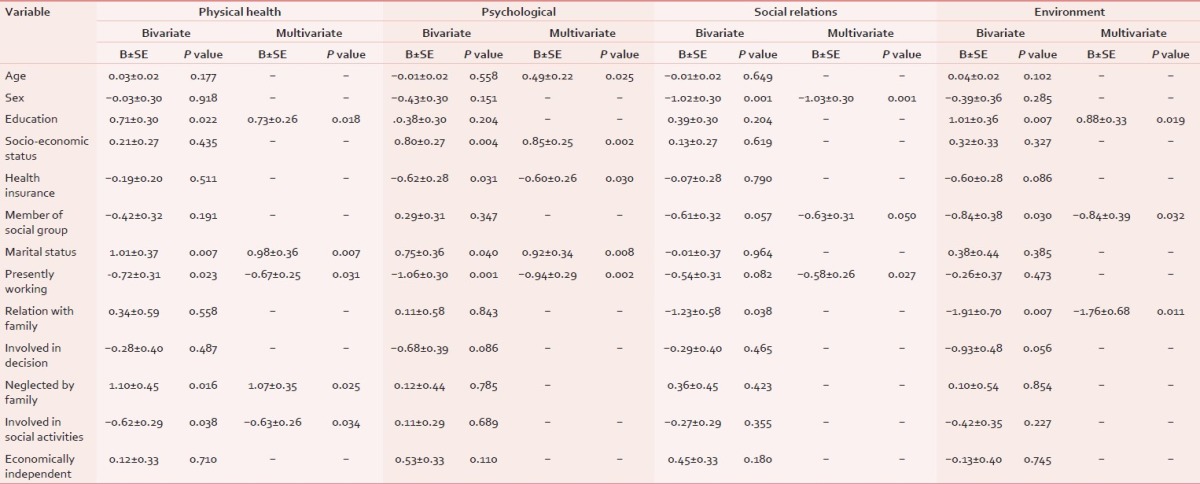

In the regression model, the five variables that emerged as significant determinants were education (P = 0.018), marital status (P = 0.007), currently working status (P = 0.031), not being neglected by the family (P = 0.025), and involvement in the social activities (P = 0.034) and accounted for 31.5% of variance in the physical quality of life score [Table 3].

Table 3.

Multivariate modeling of domains of quality of life: Stepwise multiple linear regression

Perceived psychological health

The mean scores of “perceived psychological health” was significantly higher among males (12.39) than females (11.72), among literate (12.64) than illiterate (11.75), among those who are above poverty level (12.72) than those below poverty level (11.56), among those who had health insurance (12.66) than those who did not (11.76), and among those who were currently working (12.61) than those who were not working (11.58). No significant difference in mean scores was observed across age groups, membership of social group, and marital status [Table 1].

The significantly higher mean scores were observed among those who were involved in decision making (12.40) than those who were not (11.17). But the mean scores did not differ significantly across their relationships with family members, neglect by the family, involvement in the social activity, and by their economic independence [Table 2].

The regression model suggested that the significant determinants of “perceived psychological health” were age group (P = 0.025), socio-economic status (P = 0.002), health insurance (P = 0.030), marital status (P = 0.008), and their current working status (0.002) and explained 38.4% variance in the mean score on perceived psychological health [Table 3].

Perceived social relations

We observed significantly higher mean scores for “perceived social relations” among males (14.49), literates (14.44), had health insurance (14.34), members of social groups (14.73), those married (14.07), and those who are currently working (14.24). The mean score was not statistically different in different age groups [Table 1].

Those who had good relations with the family, who were involved in decision making, there was no neglect by the family, and who were involved in social activities had higher mean scores for perceived social relations [Table 2].

Three predictors for perceived social relations were sex (P = 0.001), membership in social group (P = 0.050), and relationships with family members (P = 0.030). The final model explained 37% variance in mean scores on perceived social relations [Table 3].

Perceived environment

The differences in mean scores did not differ significantly in the different age groups. The mean score was 13.71 among men which was significantly higher than 12.49 among females. The mean scores were significantly high among literate (14.21) than among illiterate (12.52), elderly who were above poverty level (13.60) than those who were below poverty level (12.76), among those who were health insured (13.82) than those who were not health insured (12.76), and among those who were members in social groups (14.28) than those who were not members of social groups (12.76). The mean scores did not vary significantly across marital status and presently working conditions [Table 1].

Significantly high mean scores were observed for those who had a good relationship with family members (13.38) as compared to those who did not (11.70). Similarly, those who were not neglected by family involved in social activity and those who were economically independent had significant high mean scores [Table 2].

In the regression model, three predictors for “perceived environment” were education (P = 0.019), membership in social groups (P = 0.032), and relationship with family members (P = 0.011) and explained the variance of 39.2% in the mean score of perceived environment [Table 3].

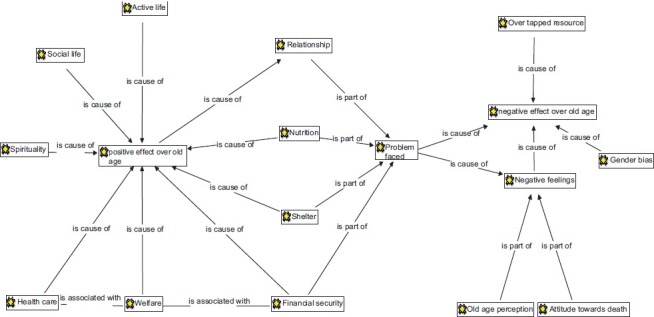

Results of focus group discussion findings

The results have been presented as a text report and a conceptual diagram. The different perspectives of the study participants have been expressed under each coding category. The conceptual diagram [Figure 1] explains how these factors (codes) relate each other and affect the quality of elderly life.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework explaining the factors affecting the quality of elderly life

Active life

Elder women are involved in household activities such as washing utensils/clothes, fetching water from the hand pump, cooking, cleaning the household and surroundings, looking after grandchildren, and shopping from nearby shops. Men do some light agricultural work such as supervision of farm work and ploughing the field. They perceived to feel better doing these activities as it gives them exercise and maintain their appetite. One of them said, “Fewer thoughts come in mind if we remain busy.” One old lady said, “It makes me feverish if i do not work.”

Social life

When enquired about social life, elders said that they spend their spare time with their colleagues. Most of them sit under a tree in village square and listen to each others’ thoughts, discuss on political issues, offer help, and sympathize to sick elderly. Here, sometimes they decide to collect money for some social activities such as celebration of religious festivals.

Spirituality

Praying to God and participating in the prayer activities were perceived to bring hope to them. It also helps to overcome their negative feeling. In rural areas, “bhajans” (a way of Hindu prayer) in temples also act as a way of gathering peoples and making them more socially active. One old lady said, “We inculcate values among our grandchildren by telling them stories and look after any sick member in the family.”

Health care, financial security, and welfare

All three of them seemed related to each other. One respondent said, “Movement of limbs is very essential for good health. Those who make less movement gets problem of joint pain, weakness and even heart disease.” For minor ailments such as cough cold and injuries, FGD respondents reported use of home remedies such as tulsi leaves, ginger, and turmeric powder. If it is not relieved, they go to local Primary Health Centre (PHC). One respondent said, “We have to pay two rupees for health care at PHC. There should not be any charge for elderly care at PHC as we have to go their more frequently. Even after paying, we get only two types of medicine for all illnesses.” When admission is required, those who can pay, go to local private hospitals which provides better medical care. Others prefer to go to a civil hospital at district place. For treatment of minor ailments, elders have to go on their own to a health facility. However, for serious health problems, family members do accompany. One respondent, who had a stressful relationship with family members, said, “I did not receive any support from my son and daughter-in-law during period of illness.” Respondents who had good relationships with family members received good care during their illness and hospitalization.

Financial security

All of them agreed need for financial security in old age. One respondent said, “I have to earn for my daily food. If i earn money, my family members behave nicely to me.” Other respondent added, “Financial conditions affect family relationships. Too excess and too less money is a problem.” One old lady said, “I need to pay someone to get my daily work done as i myself can’t do it due to my illness.” One respondent added, “Many of us do not have ancestral property. Hence, those who lack money die soon because of poor care and neglect.” Respondents said that some of them get the benefit of welfare scheme called “Niradhar yojana” in which monthly hundred rupees are given, but it was not a regular service. [Under the “Sanjay Gandhi Niradhar Anudan Yojana,” an individual (female 60 years or above and males 65 years or above) can get Rs 100 per month if he/she has no source of income. Pension amount varies across States].[12] The benefit of concession on bus and train tickets was mentioned by the participants. Those who belong to low socio-economic status reported to get the benefit of subsidized grocery from the village level ration shop. All these schemes were reported to support them to some extent. Elderly demanded free medical care through Primary Health Centres.

Relationships, shelter, and nutrition

There was a mixed reaction to perceived relationships at family level. It ranged from appreciation of good care by the family members to frustration due to complete neglect and isolation by family members. One female respondent said, “I am happy staying with my husband, but i am worried about my future after him.” Other elderly male reported, “I was happy when my wife was alive.” Other respondent added, “Husband and wife only help each other.” One male respondent said, “If someone is bedridden then no one touches him to feed and clean him except his wife” [Married people staying with spouse perceived better life than those living alone].

Another respondent said, “It's better to live with family. It offers help during serious illnesses.” Most of them were staying with their sons and staying in married daughter's house was considered against the custom. One old lady said, “Daughters are more sympathetic and better, but after marriage they have to stay away.” One respondent said, “Ultimately, you need to have money to maintain good relationships.” Respondents reported that there has to be some change in diet such as taking light semisolid food and smashed boiled items. Some of them even skip meals due to poor appetite.

Problems faced

Apart from problems in relationships, nutrition, shelter, and financial security, there are problems due to chronic illness in old age, vision and hearing problem, sleep problems, and need of assistance while doing day-to-day activities and going to toilets. One lady respondent said, “I feel weak and forgets the things quite often. It adds to my problems.” One old person said, “Old age changes your looks, speech, memory and ultimately affects your work.” It adds to negative feeling and has a negative impact on the old age life's quality. One respondent said, “Old age means pain.”

Negative feelings, old age perceptions, and attitude toward death

Most of them felt that they were less valued and were perceived as burden by family members. Most of them were experiencing family disputes. They had a feeling of worthlessness, hopelessness, and loneliness even after completing their traditional household responsibilities. One old lady cried bitterly and said, “I have got my only daughter married but my son-in-law is not good. I can’t help it and now get the feeling of worthless. Lot of thoughts comes in my mind and making me more restless.” One old lady who had lost her all three daughters said, “Old age is full with sorrows.” Other respondent said, “I got my only son married and he decided to live separately and left us alone” [Respondents perceived less utility of having children]. One respondent said, “Working in old age is not good. There is more chance that we may fall down and get badly injured. But, if we do not work, then we do not get respect in the family.”

One old man remarked, “No family member like to spend on us as long as we are alive, but they spend on our last rituals when we die.” One respondent said, “Well, death may occur at anytime and anywhere. Most of the elderly die at home or on the way. I would prefer to die at home.”

Gender bias and overtapped rtesource

Females have to suffer widowhood, old age problems, and neglect by family member. Males have to suffer if they lose their spouse. Old females have to work out of the house as labor work and return at home to do rest of the household work. Old male has to sometime go for labor work if he is separated out of the family or due to poor family financial condition.

DISCUSSION

Overall, the social determinants of perceived physical health, amenable for intervention, weretheir currently working status, not being neglected by the family, and involvement in social activities. The determinants for psychological support were health insurance and their current working status. The determinants for social relations were membership in social group and their current working status. The determinants for perceived environment were membership in social groups and their relationship with the family members. It is to be noted that subjective variables also accounted for quality of life. Several investigators in the West have recognized the importance of subjective evaluation over objective life conditions.[13]

In qualitative research, factors such as active life, social activity, spirituality, health care, involvement in decision making, and welfare schemes by the Government were found to contribute to better quality of elderly life. Apart from this, factors such as better relationship at family level, nutrition and shelter, and financial security were found essential for better quality of elderly life. Problems or conflicts in family environment, lack of shelter and financial security, overtapped resources, and gender bias adds to negative feelings in old age life. A study in Scandinavia found that satisfaction in old age life was due to four factors health and freedom from disability, involvement in hobbies and interest, intra-familial cordial relationship/understanding/co-operation, and cordial social relationships.[14]

In our study, we found 36% health insurance coverage among elderly. This finding may be context specific due to insurance schemes of MGIMS, Sewagram, and its proximity to study area. Noteworthy, it was found to be one of the determinants of psychological support. Hence, health insurance status is likely to contribute to perceived quality of life. In qualitative research, we noticed that elderly require long-term care and follow-up for chronic conditions and even a small amount of user fees raises concern in them. In the absence of health insurance and poor home care in rural area, other low-cost alternatives to hospital care such as mobile services, special camps, and ambulance services have been suggested.[15]

Membership in social groups such as self-help groups was found as one of the determinants for better perceived social relations and involvement in social activities was determinant for physical health and perceived environment. In FGDs, we found that mutual social interaction offers them an opportunity to share their problems with their colleagues. Hence, social mobilization of elderly and their involvement in some activities are likely to have positive effect on their health and social relations. The National policy for elderly, 1999, has recommended social mobilization of elderly for self-care.[8] However, its application and effect on quality of elderly life in program setting is yet to be successfully demonstrated.

National policy on old age in India intends to encourage construction and maintenance of old age homes.[7] However; we found that family was perceived as a main provider of social support and better environment for elderly care. Hence, caregiver training on the process of aging and their roles and responsibilities at this stage of life is crucial. Community-based volunteers in palliative care program in Kerala were encouraged to form local groups of elderly and start home care program for chronically sick elderly. The key roles of these volunteers were fund raising, performing nursing task such as sore management and wound care, counsel patients and family, organize social support, and organize awareness programs in the community. This program tried to address social, psychological, and health problems of elderly. Problems such as lack of food, poor housing, and children's education are better addressed by people from the same locality than by doctors or nurses.[16]

The mean scores generated for each of the domains of quality of life in this study can be used for sample size calculation for future community-based studies in the regional areas. The conceptual framework explored and explained the dynamics of factors affecting the quality of elderly life. These findings will be again useful for planning further research. However, the limitations of the present pilot study should be kept in mind. It was a small-scale study to explore the determinants of quality of elderly life in the rural area. A more diverse sample in the wider area would have allowed better exploration of quality of life across different socio-demographic characteristics.

There is need of capacity building of health care providers at facility level, education of elderly for self-care, and of caregivers at family level. Notably, it is one of the objectives of recently proposed “National Program for the National Care of the Elderly” (NPHCE).[17] Thus, apart from medical care, there is a need for intervention at the social and family level for elderly friendly environment at home and community level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are thankful to WHOQOL group, Program on Mental Health, World Health organization, Geneva, for their permission to use the WHOQOL brief questionnaire.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Census of India 2012. Online. [Last accessed on 2012 Jan 25]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/

- 2.Dey AB. Strategy for development of old age care in India. J Indian Acad Geriatr. 2006;2:146. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AE. Quality of life: A review. Educ Aging. 2000;15:419–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergman MM, editor. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2009. Advances in mixed methods research: Theories and applications. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson S, Manderson L, Tallo VL. Boston: International Nutrition Foundation for Developing Countries (INFDC); 1993. The focus group manual: Methods for social research in disease. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geneva: The World Health Organization; 2000. World Health Organization.Quality of life: WHOQOL.BREF: Australian version. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jajoo UN, Rao NS. Financing for social insurance-Wisdom from Jawar Health Insurance Scheme of Sewagram. J MGIMS. 2005;10:7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Policy on Older Persons. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. Government of India. Online. [Last accessed on 2012 Jan 25]. Available from: http://www.socialjustice.nic.in/hindi/pdf/npopcomplete.pdf .

- 9.Saldana J. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2010. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Research. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Some coding notes from responses to sexism Journals. Online. [Last accessed on 2012 Jan 25]. Available from: http://www.my.ilstu.edu/~jrbaldw/473/Reliabilty.htm .

- 11.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Old age and widow pension in Maharashtra. Online. [Last accessed on 2012 Jan 25]. Available from: http://www.disabilityindia.org/oldage.cfm#oa and wpim .

- 13.Smith AE, Sim J, Scharf T, Phillipson C. Determinants of quality of life amongst older people in deprived neighbourhoods. Ageing Soc. 2004;24:793–814. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukhopadhyay A, editor. New Delhi: Voluntary Health Association of India; 1997. Report of the Independent Commission on Health. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sivamurthy M, Wadakannavar AR. Care and support for the elderly population in India: Results from a survey of the aged in rural North Karnataka [Online] [Last accessed on 2012 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.archive-iussp.org/Brazil2001/s50/S55_P04_Sivamurthy.pdf .

- 16.Paleri A, Numpeli M. The evolution of palliative care programs in North Kerala. Indian J Palliat Care. 2005;11:15–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Program for the National Care of the Elderly. Online. [Last accessed on 2012 Jan 25]. Available from: http://www.jkhealth.org/notifications/bal456.pdf .