Abstract

The Care Pathway project used a multilevel and multimethod approach to explore access to the care pathway for diabetic renal disease. Taking what was known about the outcomes of ethnic minority patients with diabetic renal disease; the study sought to explore and further understand how and why South Asian patients’ experiences may be different from the majority of population in relation to access. Through improved understanding of any observed inequalities, the study aimed to inform the development of culturally competent diabetes services. The design incorporated audits of patient indicators for diabetes and renal health at key points in the pathway: Diagnosis of diabetes and referral to specialist renal services in two years- 2004 and 2007, and qualitative individual interviews with patients and providers identified through the 2007 samples. This article describes the care provider perspective of access to diabetes care from a thematic analysis of 14 semistructured interviews conducted with professionals, at three study sites, with different roles in the diabetes pathway. National policy level initiatives to improve quality have been mirrored by quality improvements at the local practice level. These achievements, however, have been unable to address all aspects of care that service providers identified as important in facilitating access to all patient groups. Concordance emerged as a key process in improving access to care within the pathway system, and barriers to this exist at different levels and are greater for South Asian patients compared to White patients. A conceptual model of concordance as a process through which access to quality diabetes care is achieved and its relation to cultural competency is put forward. The effort required to achieve access and concordance among South Asian patients is inversely related to cultural competency at policy and practice levels. These processes are underpinned by communication.

Keywords: Concordance, cultural competence, diabetes

Introduction

Previous studies in the UK had identified a greater relative risk for diabetes-related end stage renal failure (ESRF) in South Asians (those originating from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka),[1,2] and suggested that quality of healthcare for South Asians is inadequate and compliance poor.[3,4] There was also a low-uptake of hospital-based diabetes services, with some evidence to suggest that South Asians were subsequently referred later for renal care, and more likely to be lost to follow-up.[5] Moreover, knowledge of diabetes and its complications has been seen to be poor among South Asians.[4,6] This study – Care Pathway project – explored the concept of patient access to quality primary care – how patients gain access to services? and how services are perceived by patients and care providers? The premise being that services need to be relevant and effective if the population is to have access to quality care for improved health outcomes. The concept of access operates on multiple levels.[7] The role of healthcare providers in facilitating access includes the provision of meaningful information to support patients to make decisions about their own care.[8] Considering access in the context of primary care services and from the perspective of a diverse sample of providers can help to shed light on where, how, and for whom care could be improved in the primary care pathway for diabetes.

Policy background

National Service Frameworks for Diabetes and Renal Services were introduced in the United Kingdom in 2002 and 2006, respectively. These Frameworks provide guidance to healthcare commissioners and providers of the minimum standards of care that should be offered across the United Kingdom. Significantly, the frameworks recognized the disparity between ethnic groups and promoted a focus on earlier detection and ethnicity as a risk factor to improve outcomes for diabetic renal disease across different population groups.[9,10] Furthermore, the introduction of the quality outcomes framework indicators in primary care for diabetes in 2004 and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) reporting in 2007 were both primary-care-based infrastructure developments introduced to improve for quality of care for all patients with diabetes.[11–13] Empowerment is a core standard of the Diabetes NSF[8] and ensuring that people are informed and engaged in their care underpins the delivery of patient-centered care.[9] As diabetes management typically involves a considerable element of self-care, clinical guidelines for effective diabetes care suggest it should be aligned with needs and preferences of people with diabetes and be culturally appropriate.[14] Although it has been contested whether a generic empowerment itself is suitable for all groups of patients[15] and therefore culturally appropriate in itself, it is universally agreed that for self-management to be supported there needs to be good communication between patient and healthcare provider from the outset and there on afterwards.

Study aims

Rather than exploring the concept of empowerment in relation to access this article focuses mainly on concordance, although both were talked about by participants in the context of access and quality diabetes care. This is because as stated earlier, empowerment as a universal objective for diabetes care is contestable, and because evaluation of the care pathway explores how different stages, organizations, and human interactions relate in the system as a whole. The meaning of concordance is also dependent on different interpretations,[16] but fundamentally it concerns the interaction between service provider and patient to support diabetes management. As self-care in diabetes management involves medication, education, monitoring, support, and advice, the relations between strategies, organizations, and infrastructures that underpin these can also be considered in terms of concordance to the extent in which there is a concordance or shared approach between them which facilitates access. In a similar way that concordance is an important element of how services are delivered as well as how they are experienced by people, cultural competency as a concept can relate to the system as a whole as well as to individual face to face interactions between patient and provider. Considering how social and cultural influences interact at multiple levels of the healthcare delivery system, and devising interventions that take these into account to assure quality healthcare delivery to diverse patient populations has been put forward as one definition of the process of cultural competency.[17]

Given the policy impetus outlined earlier, this study – Care Pathway project – sought to explore how service providers viewed the progress made in delivering culturally competent services within the diabetes care pathway.

Materials and Methods

The Care Pathway project was implemented at three study sites: Leicester, Luton, and West London (Ealing) through 2006-2008. The inclusion of study sites was based on the sociodemographics of the local population to enable the inclusion of patients and providers to patients from the predominant South Asian population groups in the United Kingdom, that is, Indian Gujarati; Indian Punjabi; Pakistani; and Bangladeshi.

The design incorporated audits of patient indicators for diabetes and renal health at key points in the pathway: Diagnosis of diabetes and referral to specialist renal services in two years, 2004 and 2007, and qualitative individual interviews with patients and providers identified through the 2007 samples. This research design enabled the impact of policy and performance initiatives introduced between 2004 and 2007 to be evaluated. It also supported triangulation in the observation of patient experience between clinical outcomes, directly reported patient stories and reflections of service providers on working with patients with diabetes.

Fourteen service providers were recruited opportunistically through contacts made at each site and interviewed using a semi-structured interview schedule. The recruitment and criteria for inclusion in the sample was that interviewees were directly involved in the provision of services to people with diabetes including those recently diagnosed with diabetes.

The following participants played roles in providing care for diabetes patients: public health manager, diabetes specialist nurse, community dietitian, consultant diabetologist, diabetes and renal network manager, community health promotion worker, practice nurse, general practitioner, Link worker, community diabetes educator and community diabetes specialist nurse.

A semi-structured questionnaire had been developed specifically for the purpose of this study. This was devised by collaborating researchers (social scientists and clinicians). Both the participant information sheet and the preamble to the interview asked participants to recount their experience, in their own words, and the interview schedule was intended to be used as a guide to ensure the main areas were covered during the course of the dialogue.

One-to-one interviews were conducted by researchers at the participant's workplace; they lasted approximately for 1 h and were tape recorded. The resulting recordings were transcribed into Word documents.

The interviews explored a range of areas in diabetes care: Perceived barriers for South Asians in accessing services; perceived barriers to treatment adherence among South Asians; initiatives they may have tried in improving access to services among South Asians. Interviews explored whether the issues they raised differed or resonated with their experiences with White patients.

Analysis

Interview transcripts were repeatedly read through, an initial framework of key themes (initial thematic categories) was formulated and interviews were analyzed using these themes as well as others which emerged. The thematic approach to analysis is a widely used process in the analysis of qualitative data[18,19] and was used in this research to identify a conceptual framework of themes and sub themes which relate to the access and quality of healthcare. Analysis of data from some of these themes and sub themes forms the basis of the following results.

Results

Participants drew on examples of how services had adapted to South Asian patients’ needs to support concordance between patient and providers through clinical encounters, information and awareness raising within communities and structured patient education.

R2: ‘…so I find that when they come - if I need a link worker with me if I’m seeing a patient who can’t speak English it's great now they’ve got the training, because I can just say to them, ‘explain about this’. I can often just do a check, or whatever I’m doing, and I know that they will be able to give that information to the patient. and they will pick up things about the patients as well, because they’ve talked about and they’ll understand that issue with diabetes. So it's such an advantage, I find, having done that.’

R9: ‘We’ve used peer educators as one example in terms of getting the message across because, as healthcare professionals we can start something up, make it look fantastic, but there's no point if it's a leaflet and there's nothing to pick up, not culturally sensitive whatever. What we try to do is - we’re reminded of this every time we set something up - but fortunately as part of our diabetes network board, there's actually patients’ representative on it. When you train peer educators who’ve obviously come from a community, we don’t want to make them into a mini healthcare professional, or a mini healthcare judge, who's going to say, ‘no take three of those and two of those, that's work for somebody else.; What we want them to do is just take the key messages around the disease are to the communities that they live in and then if there are other concerns or questions they come back to healthcare professionals. But it's about the whole signposting I would guess within the community.’

R12: ‘…its impossible to see them on a one-to-one, so we are offering structured education. We’ve got a local structured education program where a patient attends two sessions, they last 3 h – each session lasts 3 h – and they run about, it's about 4 or 5 that run each month; some of them here, for example, run in dual, so you will have an English version then, whatever, Punjabi one. they are bilingual. So the added factor over-resourced isn’t really measured very well, the fact that we are able to do that. So myself, the podiatrist and the NSN we’re all bilingual, so we’re able to deliver that in two sessions, in two different languages.’

A common element of locally developed diabetes care which participants invariably brought up was the role that primary care and specifically GPs have to play in the patient pathway and identifying where there was scope for improvement.

R14: ‘…And I don’t think they understand public health and health promotion, it's not about doing – giving just leaflets, or doing some admin work. its more than that, it's looking evidence based information, it's actually about training. So they don’t think about those things; I think GPs don’t like capturing all those patients; if they don’t get paid for that they won’t do it.’

R12: ‘What we need, seriously, is making sure that there is a current, holistic overview, of what's happening with the patients. The GP must obviously find it extremely difficult; he sends the patient to me; I send reports to him on how their lifestyle and diet is. The DSNs must be sent information about how their diabetes management overall is, because of compliance of drugs and so forth and then there’ll be biochemistry – he’ll have to come up, translate all that information, say whether this patient's got a risk of renal problems and issues, or – you know, that must be an enormous task for because it's quite challenging to get an overall picture of the state of a diabetic patient.’

Other participants observed that whilst policy initiatives to increase the level of diabetes care managed in general practices had resulted in few referrals to diabetes specialists, there were still patients who did not appear to have effective diabetes care.

R13: ‘And, you know, there are some GPs that are brilliant out there, absolutely wonderful, and there are some that, you know, they’re not so good and I am not sure that those patients – well people are not being referred and this drive not to refer people, sometimes I think is a false economy, that there are patients that we need to – even if it's just a couple of visits just to straighten them out and then they can be put back into the community with pastoral care.’

R10: ‘So, and we also seem to realize that now there are more patients who come in for acute medical surgical reasons, who are under the GP only for the diabetes, who actually have extremely poor diabetes control. Obviously that complicates their illness; while they’re here we pick them up and we therefore get them into our system thereafter, not because the GPs refer them, because they come into hospital with something often unrelated to their diabetes.’

R11: ‘, and we’ve just found that, you know, patients could be diagnosed x number of years, but when they come up there’ll still be(inaudible) but nobody told them that. That's a good thing, you know, with patients coming time and time again and, you know, you may be the one that told them it in the first place…’

There was also a concern raised about the quality of checks within primary care.

R9: ‘…But we, I think that what we don’t understand is actually where is quality behind that to make sure what's recorded in terms of practice, day-to-day first, is actually what is the quality of that, and that's something we’ve always had a concern about in xxxxxxx, which is why what we’re trying to look at is – do we have a competent workforce, not so much the who but it's do we have a competent workforce to enable them to understand – ‘ah, so that's the new thinking in ethnic education, this is what's new in diabetes, this is what's new wherever;. And I think we’ve always, always driven education to healthcare professionals that's been top priority.’

R10: ‘…but of course there's a huge variation of standard and skill levels and knowledge levels and the services provided in primary care. We do have a community DSN in xxxxx but not xxxxx who has done a lot of facilitation.but there are some surgeries who, first of all, it's very difficult for her to get in due to their reluctance to have someone from outside come in potentially criticising everything you do. So it's been difficult, I mean, she has got some information on background, sort of background information on skill levels at the individual surgeries, but again it's never been properly presented and discussed at a forum, where we can therefore use the information to plan the next step in the strategy.’

Services had approached the development of diabetes care and access in different ways at the three study sites. At one site an overarching public health approach led a PCT facilitated local consultative committee was supporting a range of local services working with people with diabetes at the same time as an innovative GP led community health promotion project. At a second site there was a strong base in diabetes research, including structured patient education, originating from the university and secondary care that had developed good research collaborations with primary care and facilitated local guideline development and implementation, as well as a comprehensive website. The third site had taken a predominantly practitioner-led approach and developed an innovative program of bilingual patient education in primary care.

On the first two sites the locally developed approaches appeared to be able to harness or have become integrated and have effects wider than the initiatives themselves whereas the practitioner lead approach, in the absence of a locality wide strategy struggled to engage GP practices across the third area.

R6: ‘The GPs have been very good working with us, because of the new nGMS links. So the only part we are missing is health promotion, so whether it comes through the session here on Saturday, or whether it's done there, health promotion is being done. There are some places we are doing very good work. You can see when patients come we say ‘who's your GP, they are better monitored.’

R9: ‘The practices who are involved and those patients who are involved and those patients who are involved (in research) there's no doubt they do actually influence what else goes on in that practice. And if you have a practice nurse who is very engaged, in a sense, in some of that research, then the outcomes are going to be far better than some practices where – mm; can’t seem to keep my head above water here.’

R10: ‘…but of course there's a huge variation of standard and skill levels and knowledge levels and the services provided in primary care. We do have a community DSN in xxxxx but not xxxxx who has done a lot of facilitation.but there are some surgeries who, first of all, it's very difficult for her to get in due to their reluctance to have someone from outside come in potentially criticizing everything you do. So it's been difficult, I mean, she has got some information on background, sort of background information on skill levels at the individual surgeries, but again it's never been properly presented and discussed at a forum, where we can therefore use the information to plan the next step in the strategy.’

Discussion

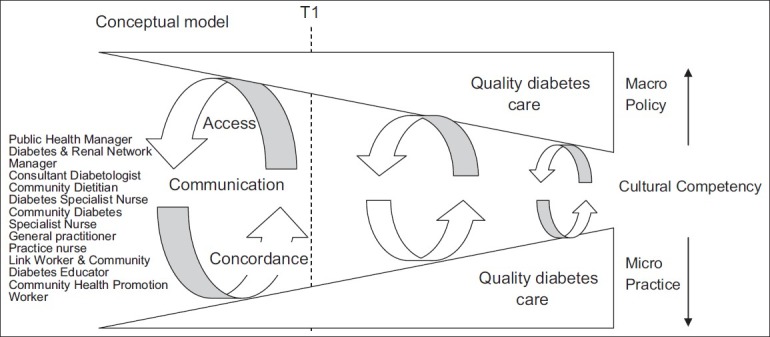

The conceptual model that has emerged from these data focuses on concordance as a process through which access to diabetes care operates [Figure 1]. The reflections on local services and the needs of local people with diabetes were articulated from a range of perspectives by professionals who provide diabetes care in three local health systems.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of concordance and cultural competency in diabetes care from interviews with service providers

Empowerment was the term used by some respondents to describe either the outcome or process, or both, of work to encourage access, better communication, and concordance. In the context of a broad definition of cultural competency, and because empowerment embodies the idea that patients are willing to take control and play an active role in their care, something that may not be the case with all groups of patients, analysis of these data has led us to focus on concordance rather than empowerment as the common process that underpins access.

Policy level initiatives to improve quality have increased and been implemented within the national healthcare system over recent years. This has been mirrored by quality improvements at local practice level. Together, the macro (policy) and micro (practice) improvements have the potential to increase the cultural competency in the system. The processes of access and concordance bridge the policy and practice levels, and at the same time are influenced by them. These processes are underpinned by communication.

At the point in time T1 when this research was being conducted, despite the quality of practical diabetes care being on an upward trajectory, the size of the effort required to bridge policy and practice to increase access was likely to be greater compared to future points in time. The model predicts that with the continued focus on reducing inequalities and improving patient-centered care, practical understanding of the process will become more widely implemented. In the same way that large wheel requires more effort to turn than a small one, our model suggests that the effort required to achieve culturally competent care is greater the further apart or less integrated policy and practice are.

For the effort to be reduced and bring the two levels closer together, our model suggests that there needs to be further top down (policy) and bottom up (practice) work that is able to harness the experience and understanding of what has gone on before and work at the level of local systems to put theory into practice. This calls for a proactive and dynamic action research approach to inequalities and access to quality diabetes care for which the shifts toward GP commissioning and the localism agenda present the opportunity.

The effort required to bring policy level drivers and those which underpin face to face encounters closer together was described variously, for example, as a need for research to understand why patients Do Not Attend; the piloting innovative approaches to engage with hard to reach patients; more training of GPs and practice staff to ensure monitoring checks are performed correctly; a shift in GP attitude towards prevention; increased level of effective communication through bilingual staff and interpreters; proactive use of routine data for health improvement in addition to payment purposes.

The respondents in our sample were directly involved in the delivery of care, so were either from the interspace, policy interface or practice base of this model. It was felt that the quality initiatives, particularly the QOF, whilst bringing about some behind the scenes improvements, had missed opportunities to directly impact on improving access or quality of diabetes care for patients.

The emergence of primary care commissioning and the re-organization of local public health authorities may maximize some of the opportunities for health improvement which participants felt had not been achieved through previous efforts. Recent white papers and the QIPP agenda encourage a local systems approach that could enable this.[20–22] Furthermore, the closer involvement of GPs in public health via local commissioning groups has the potential to improve concordance between the macro and micro levels of diabetes care.

Finally, for inequalities in access to be reduced, cultural competency of services must increase and therefore should be a key objective for local service commissioning and delivery. As cultural competency is a process of considering how sociocultural factors interact at multiple levels and devising interventions that take these issues into account[17] local health services will benefit from the evidence that care pathway research such as this, provide for understanding and delivering evidence based outcomes.

Care pathways are complex interventions and as a means of improving quality and maximizing resources are necessarily context based.[23] Local services therefore may find that broadening the understanding of concordance and applying it to the local system as a whole is a useful approach to planning and achieving effective diabetes care. Understanding how this can lead to reduced inequalities in access requires an evaluation of the local pathway as a complex intervention so that the mechanisms which bring about improvements can be identified and supported.

Conclusion

There have been improvements in diabetes services at each site since the introduction of national guidance to improve quality. These achievements, however, had been unable to address all aspects of care which service providers identified as important in facilitating access for all patient groups. Participants identified where quality improvement initiatives had missed opportunities to maximize impact, and where they also had the potential to undermine patient concordance.

Barriers to concordance exist at multiple levels in the diabetes care pathway system, and are greater for some groups of patients compared to others. A proactive approach that builds on local knowledge and experience of adapting services to meet diverse needs and addresses culture in a broad sense is most likely to be effective in achieving equity and excellence in diabetes care. GP practices are in a unique position to identify and address the diverse needs within their populations.

Reflecting on current practice in relation to concordance together with predicted trends in diabetes will be essential in planning and commissioning cost effective diabetes care in the future. Focusing on the pathway and developing a model has been a useful way of identifying some of the key concepts for improving access to quality care for South Asian patients who experience inequalities in healthcare outcomes. Research and evaluation which is integrated with local service planning and takes a systems wide approach to concordance is likely to facilitate and increase cultural competence more widely.

Acknowledgments

This study was given ethical approval by Bedfordshire NHS Research Ethics Committee in June 2005 - REC reference number: 05/Q0202/24.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This research was funded by Kidney Research UK and the Big Lottery Fund

Conflict of Interest: The authors do not have any competing interests

References

- 1.Riste L, Khan F, Cruickshank K. High prevalence of type 2 diabetes in all ethnic groups, including Europeans, in a British inner city: Relative poverty, history, inactivity, or 21st century Europe? Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1377–83. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gholap N, Davies M, Patel K, Sattar N, Khunti K. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in South Asians. Prim Care Diabetes. 2011;5:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raleigh VS. Diabetes and hypertension in Britain's ethnic minorities: Implications for the future of renal services. BMJ. 1997;314:209–13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7075.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson M, Owen D, Blackburn C. Black and minority ethnic groups in England: The second health and lifestyles survey. London: Health Education Authority; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeffrey RF, Woodrow G, Mahler J, Johnson R, Newstead CG. Indo - Asian experience of renal transplantation in Yorkshire: Results of a 10-year survey. Transplantation. 2002;73:1652–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205270-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randhawa G, Jetha C, Gill B, Paramasivan S, Lightstone E, Waqar M. Understanding kidney disease and perceptions of kidney services among South Asians in West London: Focus group study. Br J Ren Med. 2010;15:23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulliford M, Figueroa-Munoz J, Morgan M, Hughes D, Gibson B, Beech R, et al. What does ‘access to health care’ mean? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7:186–8. doi: 10.1258/135581902760082517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Care Planning in Diabetes. London: HMSO; 2006. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National service framework for diabetes: Standards. London: HMSO; 2001. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National service framework for renal services – part two: Chronic kidney disease, acute renal failure and end of life care. London: HMSO; 2005. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delivering Investment in general practice – implementing the new GMS Contract. London: HMSO; 2003. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quality and Outcomes Framework guidance. London: HMSO; 2004. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estimating glomerular filtration rate (eGFR): Information for General Practitioners. London: HMSO; 2006. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Type 2 Diabetes The management of type 2 diabetes. CG66. 2008. [Last accessed on 2008]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG66NICEGuideline.pdf .

- 15.Asimakopoulou K, Scramber S, Newton P. ‘First do no harm’ The pitfalls and stumbling blocks of empowerment. Eur Diabetes Nurs. 2010;7:79–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss M, Britten N. What is concordance? Pharm J. 2003;271:493. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O., 2nd Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritchie J, Lewis J. A guide for social science students and researchers. London: SAGE; 2008. Qualitative Research Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS. London: HMSO; 2010. Department of Health. ISBN: 9780101788120. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Healthy Lives, Healthy People: Our strategy for public health in England. London: HMSO; 2010. Department of Health. ISBN: 9780101798525. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Department of Health. QIPP. 2010. [Last accessed on 2010]. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Qualityandproductivity/QIPP/index.html .

- 23.Vanhaecht K, Panella M, Vanzelm R, Sermeus W. Is there a future for pathways. Five pieces of the puzzle? Int J Care Pathw. 2009;13:82–6. [Google Scholar]