Folate - vitamin B9- or its synthetic analogue folic acid is essential for numerous metabolic functions such as biosynthesis of RNA and DNA, repair of DNA and methylation of DNA processes that are central in the maintenance of the integrity of the genome and the cells in the body. There is great interest in assessing the potential for changes in folate intake to modulate DNA methylation both as a biomarker for folate status and as a mechanistic link to developmental disorders and chronic diseases including cancer1. Folate also acts as a cofactor in many other vital biological processes, e.g. methylation of homocysteine and coupling with vitamin B12 metabolism. It is especially important during periods of rapid cell division and growth, e.g. in pregnant women. Folate status and folate deficiency is most conveniently diagnosed by analysis of the plasma/serum folate concentration2, which is closely correlated to the erythrocyte folate concentration3.

In the diet, folates exist as polyglutamates and need to be enzymatically converted into folate monoglutamates by folate reductase in the jejunal mucosa in order to be absorbed. In contrast, folic acid is absorbed two-fold better than folates. Natural food folates are quite unstable compounds, so that losses in vitamin activity can be expected during food processing. In vegetables, up to 40 per cent of folates can be destroyed by cooking and in grains/cereals, up to 70 per cent of folates can be destroyed by milling and baking2,4.

Folate/folic acid is not per se biologically active, but is converted into dihydrofolate (by the enzyme dihydrofolate synthetase) in the liver and into tetrahydrofolate by dihydrofolate reductase; this reaction is inhibited by the anti-metabolite methotrexate. Tetrahydrofolate is converted into 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate by serine hydroxymethyltransferase5. Tetrahydrofolate as well as its methylated forms play a crucial role as methyl(ene) donors.

“Absolute” folate deficiency is most frequently due to very low dietary folate intake but may also be caused by impaired folate absorption due to gastrointestinal diseases or genetic defects in the absorption mechanisms. “Functional” folate deficiency can be elicited by mutations causing impaired activity of folate processing enzymes. Severe folate deficiency has serious consequences and may cause megaloblastic, macrocytic anaemia, polyneuropathy, diarrhoea, cognitive impairment and behavioural disorders. Low levels of blood folate lead to increased plasma homocysteine, impaired DNA synthesis and DNA repair and may promote the development of some forms of cancers6.

The preventive effect of a high folic acid intake against neural tube defects (NTD) is one of the most important nutritional discoveries7. Folate requirements are increased in life stages with amplified cell division such as pregnancy. It is assumed that on a population level, nutritional requirements for folate cannot be completely covered by a varied diet, as recommended by the National Health Authorities in the Nordic Countries8. Dietary intake is below recommendations in several Western societies, especially in populations of low socio-economic status owing to low consumption of folate-rich foods, e.g. pulses, citrus fruits, and leafy vegetables. It is estimated that an additional intake of 50-180 μg folate would allow most people to reach the recommendations9.

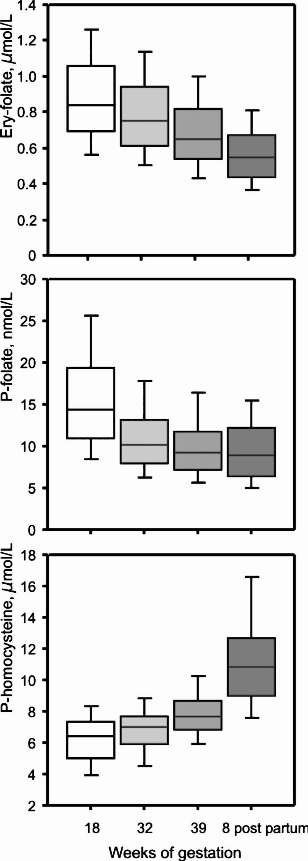

The most well-known consequences of folate deficiency are associated with pregnancy and may have serious impact on the foetus and newborn infant. Plasma folate and erythrocyte folate both decline during pregnancy and postpartum, probably due to increased folate demands combined with an inadequate folate intake3. From 18 wk gestation to 8 wk postpartum, the frequency of low plasma folate <3 μg/l (<6 nmol/l) increases from 1 to 19 per cent3. In addition, plasma homocysteine levels increase steadily during pregnancy and postpartum3. Denmark has not introduced folic acid fortification of food. Therefore, the Danish Health Authorities has since 1997 recommended 400 μg folic acid daily to women of reproductive age one month prior to conception and during the first trimester of pregnancy10. A survey in 200311 showed that only 13 per cent of pregnant women followed these guidelines. The prevalence of folate deficiency in pregnant women in middle- and far-east countries is disturbingly high (e.g. Lebanon 25%, Malaysia 15-22%, Turkey 72%) as inadequate intake of folate/folic acid is a major risk factor for NTD12. In addition, an increased risk of other malformations, e.g. cardiovascular defects, urinary tract defects and oral clefts has been reported. This has motivated many countries to introduce fortification of staple foods with folic acid13, which effectively has decreased the prevalence of NTD, e.g. in USA and Canada14. In most countries, the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for folate is 300 μg/day for adults and 400-500 μg/day for women of childbearing age and pregnant women15,16.

Fig.

Plasma folate, erythrocyte folate and plasma homocysteine in healthy Danish women during pregnancy and 8 wk postpartum. The women took no folic acid supplements (Source: Ref. 3). [Reprinted with permission from John Wiley & Sons Ltd., UK: Eur J Haematol2006; 76: 200-5].

In order to maintain an adequate folate status, the intake of folates/folic acid should be appropriate and the absorption processes of folates/folic acid in the small intestine should function properly. The absorption of folate has been a subject for intensified investigation during the last decade and steadly progress has been made to clarify the complex absorption mechanisms. The paper of Wani et al17 in this issue casts new light on folate absorption in the small intestine. Colonic bacteria may synthesize folate and a carrier-mediated, pH-dependent, folate uptake mechanism was reported in human colonic luminal membranes in 199718, and some years later this mechanism was further clarified by the discovery of the human reduced folate carrier (RFC) in the colonic mucosa19. A human proton-coupled, high-affinity folate transporter (PCFT) was identified in 2006 and it was demonstrated that a loss-of-function mutation in this gene can be the molecular basis for autosomal recessive hereditary folate malabsorption20. Recently, nuclear respiratory factor 1 has been identified as a major inducible transcriptional regulator of PCFT gene expression21. Thus folate appears to be absorbed both in the small intestine and colon, with a decreasing absorptive gradient from jejunum to colon. The long absorptive pathway could be a consequence of the very important function of folate in maintaining genetic body homeostasis.

After Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, many patients develop folate deficiency. This highlights the importance of the high absorptive capacity for folate in the acidic milieu in duodenum and proximal jejunum, which is eliminated by the operation22. However, a daily supplement of 400 μg folic acid is sufficient to alleviate deficiency, because the absorptive capacity in the remaining part of the intestines is able to compensate for the lost absorption in the proximal part of the small intestine.

Folate deficient rats did not thrive compared to their folate replete mates17. Severe, long-standing folate deficiency may cause gastrointestinal problems and in theory this might impair the production of mRNA and DNA necessary for synthesis of RFC and PCFT and introduce a vicious circle of folate malabsorption. Wani et al17 studied the aspects of intestinal folate uptake in folate replete and folate deficient rats using the technique of intestinal brush border membrane vesicles (BBMV) from isolated small intestinal epithelial cells. They showed that folate deficiency for a (short) period of 90 days in rats caused a physiological and beneficial upregulation of the absorptive mechanisms in the proximal 2/3rd of the small intestine17. The uptake of folic acid was pH dependent with a maximum at acidic pH of 5.5. It followed the enzyme kinetics of Michaelis-Menten consistant with a carrier-mediated transport. Further, the uptake was dependent on temperature showing a decrease at temperatures below 37°C.

Young enterocytes are made by division of enterocyte “stem” cells at the crypt base and mature gradually as they move towards the villus tip where they die and are exfoliated. The results of Wani et al17 showed that folic acid uptake increased with increasing maturity of the enterocytes and was highest in the cells located at the tip of the villus. This finding was further substantiated by significantly higher levels of mRNA for RFC and PCFT in BBMV from folate deficient rats compared to folate replete rats and increasing expression of mRNA for RFC and PCFT in enterocytes along the crypt-villus axis. The increase in specific mRNA resulted in an increased expression of both the RFC and PCFT proteins as confirmed by Western blot analysis. Furthermore, using labelled S-adenosylmethionine, there was evidence of a decreased methylation rate of DNA in folate deficient rats in comparison with their folate replete mates.

In conclusion, this thorough, detailed and exhaustive scientific evidence presented by Wani & colleagues17 has to a great extent contributed to increase our knowledge and understanding of the complexity of the intestinal absorption of folic acid. Hopefully, their findings can be interpreted and employed to elaborate a better prevention and combat against the global problem of human folate deficiency.

References

- 1.Crider KS, Yang TP, Berry RJ, Bailey LB. Folate and DNA methylation: a review of molecular mechanisms and the evidence for folate's role. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:21–38. doi: 10.3945/an.111.000992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benoist B. Conclusions of a WHO Technical consultation on folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29(Suppl):S238–44. doi: 10.1177/15648265080292S129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milman N, Byg K-E, Hvas A-M, Bergholt T, Eriksen L. Erythrocyte folate, plasma folate and plasma homocysteine during normal pregnancy and postpartum: a longitudinal study comprising 404 Danish women. Eur J Haematol. 2006;76:200–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caudill MA. Folate bioavailability: implications for establishing dietary recommendations and optimizing status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1455S–60S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28674E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balion C, Kapur BM. Folate. Clinical utility of serum and red blood cell analysis. Clin Lab News. 2011;37:8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstein SJ, Hartman TJ, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Pietinen P, Barrett MJ, Taylor PR, et al. Null Association between prostate cancer and serum folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and homocysteine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:1271–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katan MB, Boekschoten MV, Connor WE, Mensink RP, Seidell J, Vessby B, et al. Which are the greatest recent discoveries and the greatest future challenges in nutrition? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:2–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordic Nutrition Recommendations NNR 2004 Integrating Nutrition and Physical Activity. Stockholm, Sweden: Nordic Council of Ministers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Bree A, van Dusseldorp M, Brouwer IA, van het Hof KH, Steegers-Theunissen RPM. Review folate intake in Europe: recommended, actual and desired intake. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51:643–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folate and neural tube defects (folat og neuralrørsdefekter) Publication no.285. Copenhagen: National Food Agency of Denmark; 1997. National Food Agency of Denmark (Levnedsmiddelstyrelsen) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folate and neural tube defects (folat og neuralrørsdefekter) Publication no.2003:01. Copenhagen: National Food Agency of Denmark; 2003. National Food Agency of Denmark (F#248;devaredirektoratet) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell LE, Adzick NS, Melchionne J, Pasquariello PS, Sutton LN, Whitehead AS. Spina bifida. Lancet. 2004;364:1885–95. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17445-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [accessed on May 14, 2012]. Available from: http://www.sph.emory.edu/wheatflour/

- 14.Mosley BS, Cleves MA, Siega-Riz AM, Shaw GM, Canfield MA, Waller DK, et al. Neural tube defects and maternal folate intake among pregnancies conceived after folic acid fortification in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:9–17. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Nordic nutrition recommendations. 4th ed. Copenhagen: Norden; 2004. Nordic Council of Ministers; pp. 287–96. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly D, O’Dowd T, Reulbach U. Use of folic acid supplements and risk of cleft lip and palate in infants: a population-based cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:466–72. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X652328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wani NA, Thakur S, Kaur J. Mechanism of intestinal folate transport during folate deficiency in rodent model. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136:758–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudeja PK, Torania SA, Said HM. Evidence for the existence of a carrier-mediated folate uptake mechanism in human colonic luminal membranes. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G1408–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.6.G1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dudeja PK, Kode A, Alnounou M, Tyagi S, Torania S, Subramanian VS, et al. Mechanism of folate transport across the human colonic basolateral membrane. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G54–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.1.G54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu A, Jansen M, Sakaris A, Min SH, Chattopadhyay S, Tsai E, et al. Identification of an intestinal folate transporter and the molecular basis for hereditary folate malabsorption. Cell. 2006;127:917–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonen N, Assaraf YG. The obligatory intestinal folate transporter PCFT (SLC46A1) is regulated by nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF-1) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:33602–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.135640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aarts EO, van Wageningen B, Janssen IM, Berends FJ. Prevalence of anemia and related deficiencies in the first year following laparoscopic gastric bypass for morbid obesity. J Obes. 2012;193705 doi: 10.1155/2012/193705. E pub 2012, Mar13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]