Abstract

Amantadine and dextromethorphan suppress levodopa (L-DOPA)-induced dyskinesia (LID) in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and abnormal involuntary movements (AIMs) in the unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) rat model. These effects have been attributed to N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonism. However, amantadine and dextromethorphan are also thought to block serotonin (5-HT) uptake and cause 5-HT overflow, leading to stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors, which has been shown to reduce LID. We undertook a study in 6-OHDA rats to determine whether the anti-dyskinetic effects of these two compounds are mediated by NMDA antagonism and/or 5-HT1A agonism. In addition, we assessed the sensorimotor effects of these drugs using the Vibrissae-Stimulated Forelimb Placement and Cylinder tests. Our data show that the AIM-suppressing effect of amantadine was not affected by the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100635, but was partially reversed by the NMDA agonist d-cycloserine. Conversely, the AIM-suppressing effect of dextromethorphan was prevented by WAY-100635 but not by d-cycloserine. Neither amantadine nor dextromethorphan affected the therapeutic effects of L-DOPA in sensorimotor tests. We conclude that the anti-dyskinetic effect of amantadine is partially dependent on NMDA antagonism, while dextromethorphan suppresses AIMs via indirect 5-HT1A agonism. Combined with previous work from our group, our results support the investigation of 5-HT1A agonists as pharmacotherapies for LID in PD patients.

Keywords: 6-hydroxydopamine, dyskinesia, L-DOPA, Parkinson’s disease, serotonin

Introduction

Levodopa (L-DOPA) is the primary treatment for Parkinson’s disease (PD). Unfortunately, its long-term administration causes disabling chorea-like side effects, known as L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia (LID) in human patients and abnormal involuntary movements (AIMs) in the unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-treated rat, an animal model of PD. These side effects are generally attributed to dopamine (DA) receptor upregulation, dysregulation of DA transmission and maladaptive changes in striatal synaptic plasticity (Lindgren et al., 2010; Mela et al., 2012). Pharmacotherapies for LID initially targeted the glutamatergic N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor (Blanchet et al., 1997; Chase et al., 2000) based on a hypothesis of overactivity of glutamatergic corticostriatal projections onto medium spiny neurons forming the direct pathway.

Preclinical and clinical evidence has emerged to support the serotonin (5-HT) 1A (5-HT1A) receptor as a possible pharmacological target for LID suppression. Specifically, it has been proposed that release of DA from 5-HT neurons as a false neurotransmitter may contribute to dyskinesia development (Carta et al., 2007), and 5-HT neurons have been shown to sprout and potentiate DA release in response to L-DOPA (Rylander et al., 2010). Following this logic, stimulation of 5-HT1A autoreceptors, which dampens the unregulated DA release from presynaptic serotonergic neurons, should ameliorate these side effects. In support of this hypothesis, LID in PD patients has been shown to be suppressed by 5-HT1A agonists, including buspirone (Bonifati et al., 1994), sarizotan (Olanow et al., 2004) and tandospirone (Kannari et al., 2002). Similarly, AIMs in the 6-OHDA rat are suppressed by the 5-HT1A agonist 8-OH-DPAT (Tomiyama et al., 2005; Dupre et al., 2007, 2008), as well as buspirone (Lundblad et al., 2005; Eskow et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2009a,b; Paquette et al., 2009a). Furthermore, AIMs are suppressed by removal of 5-HT projections with the neurotoxin 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine (Carta et al., 2006; Eskow et al., 2009) and are exacerbated by intrastriatal transplants of 5-HTergic neurons (Carlsson et al., 2007).

Based on this evidence, we hypothesized that 5-HT1A agonism might be an additional or alternative pharmacological mechanism underlying the AIM-suppressing effect of amantadine and dextromethorphan (DM), traditionally thought to act via other mechanisms. Both drugs have been shown to suppress LID in PD patients (amantadine: Verhagen Metman et al., 1998b,c; Metman et al., 1999; Del Dotto et al., 2001; DM: Verhagen Metman et al., 1998a,b; Verhagen-Metman et al., 1998b) and AIMs in the 6-OHDA rat (amantadine: Lundblad et al., 2002; Dekundy et al., 2007; DM: Paquette et al., 2008). These effects were attributed to NMDA antagonism (Verhagen Metman et al., 1998a,b; Verhagen-Metman et al., 1998b; Chase et al., 2000; Marin et al., 2000; Del Dotto et al., 2001), as amantadine, DM, and DM’s active metabolite dextrorphan are known to block the NMDA channel (Sills & Loo, 1989; Kornhuber et al., 1991; Netzer et al., 1993; Church et al., 1994; Parsons et al., 1995). However, amantadine and DM were also found to induce 5-HT overflow (Baptista et al., 1997; Gaikwad et al., 2005) via blockade of the 5-HT reuptake protein (Meoni et al., 1997; Werling et al., 2007), which could indirectly activate 5-HT1A receptors (Kamei et al., 1991; Kamei, 1996). In the current studies, we investigated the mechanisms underlying the AIM-suppressing effects of amantadine and DM, based on systemic administration of the NMDA agonist d-cycloserine (DCS) and the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100635.

Treatments that block the adverse effects of L-DOPA while limiting its therapeutic action would be of little use clinically. Therefore, we incorporated sensorimotor assessment to determine the effects of test drugs when administered in combination with L-DOPA. For this, we selected two tests that have been previously used in dyskinetic 6-OHDA rats: the Vibrissae-Stimulated Forelimb Placement (VSFP) test (Lindner et al., 1996; Monville et al., 2005; Paquette et al., 2010) and the Cylinder test (Lundblad et al., 2002; Paquette et al., 2010).

Materials and methods

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA) and the Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC). Both locations are certified by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Animals

Male Wistar rats (n = 8–9 per group; Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA) weighing 275–300 g at surgery were used at UTHSCSA, while male Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 7–8 per group; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) weighing 300 g at surgery were used at the Portland VAMC. Rats were housed on a 12-h light/dark cycle and were given food and water ad libitum. Testing was conducted between 09:00 and 15:00 h.

6-OHDA lesions

6-OHDA lesioning was conducted via stereotaxic surgery as previously described (UTHSCSA: Moregese et al., 2007; Portland VAMC: Paquette et al., 2008, 2009a, 2010). Briefly, Wistar rats were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/mL), xylazine (100 mg/mL) and acepromazine (10 mg/mL), dissolved in saline (0.085 mL/kg, i.p.), and a 30-gauge needle attached to a 10-μL Hamilton syringe mounted directly on a stereotaxic apparatus was used to infuse 6-OHDA HCl (8 μg/2 μL in 0.9% saline with 0.1% ascorbic acid, which was delivered at 0.5 μL/min) into the left medial forebrain bundle (AP −4.3, ML ±1.6, DV −8.3 mm from Bregma). Sprague Dawley rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, and a 30-gauge infusion cannula, attached via PE20 tubing to a 25-μL Hamilton gastight syringe and driven by a microinfusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA), was used to infuse 6-OHDA HBr (22.8 μg/2 μL in 0.9% saline with 0.2% ascorbic acid, delivered at 0.5 μL/min into each of two sites for a total of 45.6 μg/4 μL; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) within the right medial forebrain bundle (AP −4.3 and −4.8, ML ±1.2, DV −8.6 mm from Bregma). For all surgeries, rats were pretreated with desipramine HCl (25 mg/kg, i.p., in milliQ water; Sigma) at least 30 min prior to receiving 6-OHDA. An a priori criterion of an average of ≥5 turns/min over 10 consecutive minutes in response to amphetamine (2.5 mg/kg for Wistar rats, 5 mg/kg for Sprague–Dawley rats) was used to select rats with significant hemi-parkinsonism (Chang et al., 1999).

Drugs

L-DOPA methyl ester, benserazide hydrochloride, l-ascorbic acid, d-amphetamine sulfate, N-[2-[4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1-piperazinyl)ethyl)-N-2-pyridinylcyclohexanecarboxamide maleate (WAY-100635), DCS, amantadine hydrochloride and DM were obtained from Sigma. WAY-100635 and DM were dissolved in milliQ water; all other drugs were dissolved in 0.9% saline. Amantadine was administered s.c. at 100 min prior to L-DOPA (Lundblad et al., 2002; Dekundy et al., 2007), while WAY-100635, DCS and DM were administered i.p. at 30 min prior to L-DOPA. All drugs were administered at 0.1 mL/100 g of body weight, except for DM, which was administered at 0.2 mL/100 g of body weight. Rats in each experiment were tested in randomized order using a within-subjects design with test days separated by at least 48 h. As the efficacy of amantadine was observed to decrease over repeated administration in the same animals, the amantadine study was divided into two experiments, amantadine + WAY and amantadine + DCS, each of which was conducted using a within-subjects design in a different cohort of rats.

Doses of drugs were selected based on previous data from our laboratory and others. For amantadine, we selected a dose of 60 mg/kg, as other groups have shown suppression of AIMs with 40–60 mg/kg in 6-OHDA rodents (Lundblad et al., 2002, 2005; Dekundy et al., 2007), and a pilot study in our laboratory revealed greater anti-dyskinetic effects at 60 mg/kg than at 40 mg/kg (data not shown). For DM, we selected a dose of 45 mg/kg, which we previously showed to effectively suppress AIMs (Paquette et al., 2008). For WAY-100635, we selected a dose of 0.4 mg/kg, as this dose had no effect on AIMs by itself, and we had previously observed that 0.5 mg/kg WAY-100635 alone increased AIMs during the first hour after L-DOPA (Paquette et al., 2009a). For DCS, a partial agonist acting at the strychnine-insensitive glycine site of the NMDA receptor, we selected 15 mg/kg, a dose that has been shown to act as an NMDA agonist (Walker et al., 2002); higher doses (50–200 mg/kg, i.p.) produce effects similar to those of the NMDA antagonists MK-801 and phencyclidine (Depoortere et al., 1999).

L-DOPA treatment

At least 24 h after rotational screening with amphetamine, Wistar rats received one injection of L-DOPA methyl ester HCl (6 mg/kg, s.c.) combined with benserazide HCl (12.5 mg/kg, s.c.) for 12 consecutive days to induce AIMs. Sprague–Dawley rats received one injection of L-DOPA methyl ester HCl (7.5 mg/kg, i.p.), combined with benserazide HCl (15 mg/kg, i.p.) and ascorbic acid (2.6 mg/kg, i.p.) for 21 consecutive days. In both experiments, after this subchronic treatment period, rats were switched to a maintenance regimen of 2–3 injections/week of L-DOPA with at least 48 h between injections, and the effects of putative antidyskinetic drugs were tested on these maintenance injection days.

AIMs assessment

AIMs were assessed by an investigator blind to treatment, as previously described by our group for Wistar (Moregese et al., 2007, 2009) and Sprague–Dawley rats (Paquette et al., 2008, 2009a, 2010) using an adaptation of the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale described by Cenci et al. (1998). Briefly, each rat was rated on a scale of 0 (absent) to 4 (most severe) for each AIM category (limb, axial and oral dyskinesias, and contraversive rotation) for 1 min every 20 min. Ratings were based on the amount of observation time that the behaviors were displayed: 0, absent; 1, present for less than half of the observation time; 3, present for more than half of the observation time and able to be interrupted by external stimuli (i.e. tapping on the observation chamber); 4, present for more than half of the observation time and not able to be interrupted by external stimuli. Dyskinesias were defined as follows: limb, repeated back-and-forth or circular movements and stutterstepping during locomotion; axial, contralateral posture of the neck or torso, including falling into a supine position; oral, chewing and tongue protrusions.

Sensorimotor assessment

Rats were subjected to the sensorimotor battery at baseline (prior to the lesion), 2 weeks after the 6-OHDA lesion, and on drug testing days.

VSFP test

The VSFP test has previously been used in dyskinetic rats (Lindner et al., 1996; Monville et al., 2005; Paquette et al., 2010). It was conducted at 15–30 min after L-DOPA. Briefly, rats were held around the torso with their bodies parallel to the floor and one forelimb unrestrained and then were moved downward toward a table top until the vibrissae ipsilateral to the unrestrained limb touched the surface. Rats’ vibrissae remained in contact with the table as they were moved downward along the table leg, allowing approximately 5 s for the animals to complete each trial. The percentage of successful placements out of ten trials was calculated for each forelimb.

Cylinder test

We used a variation of the Cylinder test developed by Schallert et al. (2000) and previously used in dyskinetic rats (Lundblad et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2009a,b; Paquette et al., 2010; Riddle et al., 2011). The Cylinder test was conducted 30–70 min after L-DOPA. Rats were placed in a clear Plexiglas cylinder (19.5 cm i.d. × 30 cm high) with a clear Plexiglas floor. All weight-bearing forepaw placements on the walls of the cylinder, defined as full apposition of the paws with open digits, were scored as ipsilateral, contralateral (to the 6-OHDA lesion) or simultaneous. Specifically, individual ipsilateral or contralateral paw placements were scored when either paw contacted the wall and was removed prior to any other contacts. Simultaneous paw placements were scored when both paws contacted the wall prior to either being removed, even if there was a temporal delay between the two contacts. Each test session lasted for 1 min from the time of the first forepaw placement on the cylinder walls. When necessary, animals were encouraged to place forepaws on the cylinder walls by covering the cylinder with a dark cloth or by agitating the cylinder with a gentle back-and-forth or turning motion. A minimum of three placements was required for data to be included in analysis.

Lesion size quantification

In the neostriatum, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) loss was 92.46 ± 0.73% in Wistar and 91.69 ± 0.74% in Sprague–Dawley rats. In the ventral mesencephalon, TH loss was 78.28 ± 6.24% in Sprague–Dawley rats, but was not measured in Wistar rats. These values were determined by TH Western-blotting, as previously described (Paquette et al., 2008, 2009a). Briefly, samples (15–20 μg) were separated on a 10% Criterion Tris–HCl polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA; 200 V, 1 h), then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (100 V, 1 h) and exposed to monoclonal primary TH antibody (1 : 40 000; Immunostar #22941, Hudson, WI, USA) and goat anti-mouse antibody (1 : 3000; Bio-Rad #170-6520). Samples from Wistar rats were visualized using ECL (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA) followed by exposure to X-ray film (ISC Bioexpress, Kaysville, UT, USA). Band immunoreactivity was analysed by densitometry using NIH imaging software. Samples from Sprague–Dawley rats were visualized using ECF (Amersham) and quantified using the Typhoon fluorescence detection system (Typhoon 9410 Variable Mode Imager; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA; emission filter: 520 BP40, Laser: 488 Blue2).

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS (Chicago, IL, USA) with correction for multiple comparisons and P ≤ 0.05 considered significant. A two-way anova (time × treatment) was used to analyse AIM scores over time within each session. Total AIM scores (axial + limb + oral, ALO) summed across the full 3-h sessions or across the first hour of the sessions were analysed by one-way anova (for more than two groups) or Student’s t-test (for two groups). When AIM data violated homogeneity of variance assumptions, Greenhouse–Geisser corrections or t-tests in which equal variance was not assumed were used for repeated or between-subjects data, respectively, yielding fractional degrees of freedom. Sensorimotor behaviors were analysed using a non-directional Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test when data violated homogeneity of variance.

Results

Abnormal involuntary movement

Not all Wistar rats that passed amphetamine screening expressed AIMs, and Wistar rats with scores for ALO AIMs < 5 over the full 3-h test period in response to L-DOPA were excluded. Conversely, as in our previous studies, all Sprague–Dawley rats that passed amphetamine screening expressed AIMs, although the severity of AIMs showed some variability across test days.

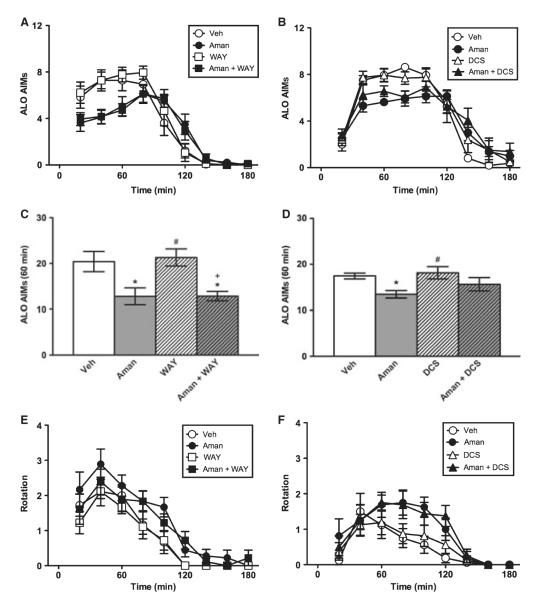

Experiment 1: amantadine in Wistar rats

Wistar rats expressed AIMs over time in both the WAY-100635 (F4.32,138.35 = 84.63, P < 0.001) and DCS experiments (F4.49,125.68 = 84.63, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1A and B). Amantadine had a modest AIM-suppressing effect, which was not affected by the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100635 (0.4 mg/kg), but was partially reversed by the NMDA agonist DCS (15 mg/kg). The time × treatment interaction effects were significant (F12.97,138.35 = 3.20, P < 0.001 and F13.47,125.68 = 2.48, P < 0.01, respectively), but the effects of treatment were not significant (F3,32 = 1.34, P > 0.05 and F3, 28 = 0.34, P > 0.05, respectively). During the first hour, amantadine suppressed AIMs, and this outcome was not affected by WAY-100635, but was partially reversed by DCS (Fig. 1C and D). When the full 3-h session was assessed, the AIM-suppressing effect of amantadine was no longer apparent (data not shown). The axial subscale showed a significant time × treatment interaction effect in the WAY-100635 experiment (F12.85,137.09 = 3.11, P < 0.001), and the limb and oral subscales showed significant interaction effects in both the WAY-100635 and DCS experiments (all F ≥ 1.81, all P < 0.05; data not shown). The oral subscale also showed a significant treatment effect in the WAY-100635 experiment (F3,32 = 2.94, P < 0.05; data not shown). L-DOPA-induced rotation did not show a significant time × treatment interaction effect (all F ≤ 1.11, all P > 0.05), but the treatment effect was significant in the WAY-100635 experiment (F3,32 = 3.96, P < 0.05) and showed a statistical trend in the DCS experiment (F3,32 = 2.52, P = 0.078) (Fig. 1E and F). These treatment effects were driven by a slight increase in rotation in animals treated with amantadine. In the first hour, planned comparisons showed that amantadine had no effect on rotation in the WAY-100635 or DCS experiments (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Experiment 1. Amantadine in Wistar rats. Relative to vehicle (Veh), amantadine suppressed AIMs over time (A, B) and in the first hour of the test (C, D). The AIM-suppressing effect of amantadine was reversed by DCS (15 mg/kg, B and D) but not WAY-100635 (0.4 mg/kg, A and C) at doses that had no effect alone, demonstrating dependence on NMDA but not 5-HT1A receptors. Amantadine caused a non-significant increase in L-DOPA-induced rotation (E–F). *P < 0.05 relative to Veh; #P < 0.01 relative to Aman, +P < 0.001 relative to WAY.

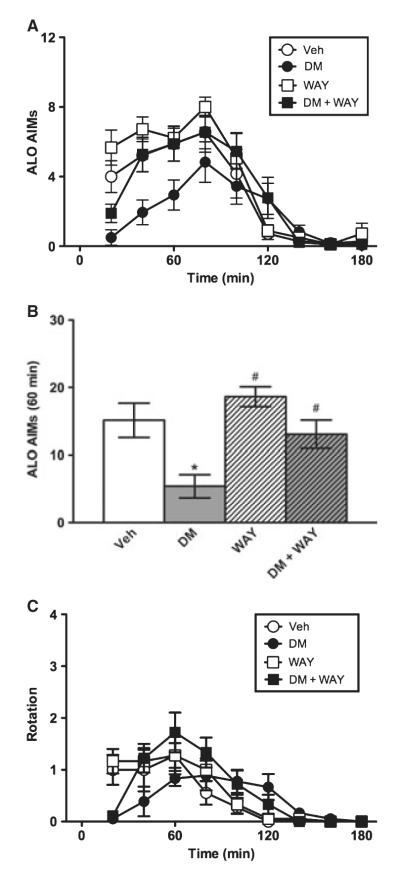

Experiment 2: DM in Wistar rats

As in Experiment 1, Wistar rats expressed AIMs over time (F4.33,138.48 = 49.66, P < 0.001). However, while the AIM-suppressing effect of amantadine was insensitive to WAY-100635, that of DM was reversed by WAY-100635 (0.4 mg/kg). The time × treatment interaction effect was significant (F4.33,138.48 = 2.79, P ≤ 0.001), and the effect of treatment was significant (F3,32 = 3.07, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). During the first hour, DM suppressed AIMs, and this effect was completely blocked by WAY-100635 (Fig. 2B). When the full 3-h session was assessed, the AIM-suppressing effect of DM was no longer apparent (data not shown). The axial and limb subscales showed significant time × treatment interaction effects (all F ≥ 2.37, all P < 0.01), and the axial subscale also showed a significant treatment effect (F3,32 = 4.36, P ≤ 0.01), while the limb subscale showed a statistical trend for treatment (F3,32 = 2.67, P = 0.064) (data not shown). L-DOPA-induced rotation showed a significant time × treatment interaction effect (F3.85,123.14 = 3.00, P ≤ 0.001), but the treatment effect did not reach significance (F3,32 = 0.74, P > 0.05) (Fig. 2C). In the first hour, planned comparisons revealed that DM showed a statistical trend to suppress rotation relative to vehicle (P = 0.078), and WAY-100635 prevented this trend (P < 0.05) (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Experiment 2. Dextromethorphan in Wistar rats. Relative to vehicle (Veh), DM suppressed AIMs over time (A) and in the first hour of the test (B). The AIM-suppressing effect of DM was reversed by WAY-100635 (0.4 mg/kg, B), demonstrating its dependence on 5-HT1A receptors. DM caused a non-significant decrease in L-DOPA-induced rotation (C). *P < 0.05 relative to Veh; #P < 0.01 relative to DM.

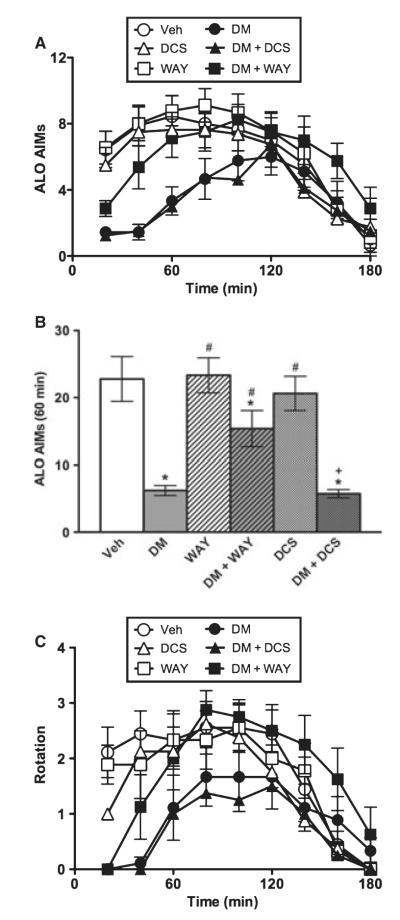

Experiment 3: DM in Sprague–Dawley rats

Although multiple doses of amantadine were tested in Sprague–Dawley rats, including doses that have been shown to suppress AIMs in other studies, no anti-dyskinetic effects of amantadine were observed in this strain. Therefore, only the effects of DM are reported for Sprague–Dawley rats, and possible reasons for amantadine’s lack of effect in this strain are reviewed in the discussion.

Sprague–Dawley rats expressed AIMs over time (F4.67,210.30 = 40.03, P < 0.001). Consistent with our previous report (Paquette et al., 2008), DM suppressed AIMs in this strain. This AIM-suppressing effect was reversed by WAY-100635 (0.4 mg/kg), but was not affected by DCS (15 mg/kg). The time × treatment interaction effect was significant (F4.67,210.30 = 3.49, P < 0.001), and the effect of treatment was significant (F5,45 = 2.54, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A). During the first hour, DM suppressed AIMs, and this effect was partially reversed by WAY-100635, but not by DCS (Fig. 3B). When the full 3-h session was assessed, the AIM-suppressing effect of DM was blocked by WAY-100635, and rats treated with DM + WAY-100635 were indistinguishable from vehicle-treated controls (data not shown). The axial and limb subscales showed significant time × treatment interaction effects (all F ≥ 2.25, all P < 0.01), and the limb subscale also showed a significant treatment effect (F5,45 = 4.05, P < 0.01), while the oral subscale showed statistical trends for time × treatment (F5.59,251.39 = 1.39, P = 0.097) and treatment (F5,45 = 2.23, P = 0.068) (data not shown). L-DOPA-induced rotation showed a significant time × treatment interaction effect (F4.64,208.92 = 2.72, P < 0.001), but the treatment effect did not reach significance (F5,45 = 1.91, P > 0.05) (Fig. 3C). In the first hour, planned comparisons showed that DM suppressed rotation relative to vehicle (P < 0.001), and WAY-100635 prevented this effect (P < 0.05), but DCS had no effect (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Experiment 3. Dextromethorphan in Sprague–Dawley rats. Relative to vehicle (Veh), DM suppressed AIMs over time (A) and in the first hour of the test (B). The AIM-suppressing effect of DM was reversed by WAY-100635 (0.4 mg/kg, B) but not DCS (15 mg/kg, B), demonstrating dependence on 5-HT1A but not NMDA receptors. DM significantly decreased L-DOPA-induced rotation in the first hour of the test, and this effect was reversed by WAY-100635, but not DCS (C).*P < 0.05 relative to Veh; #P < 0.01 relative to DM, +P < 0.001 relative to DCS.

Sensorimotor assessment

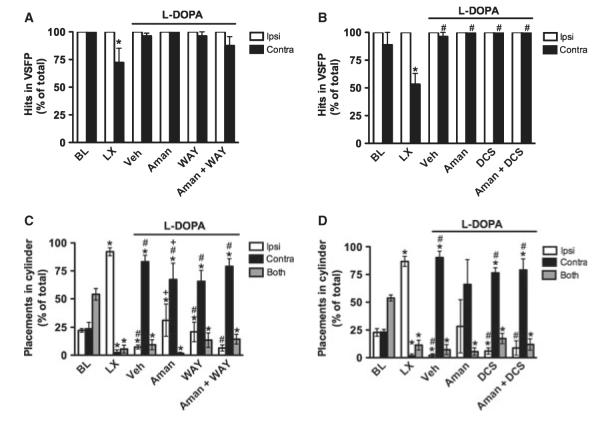

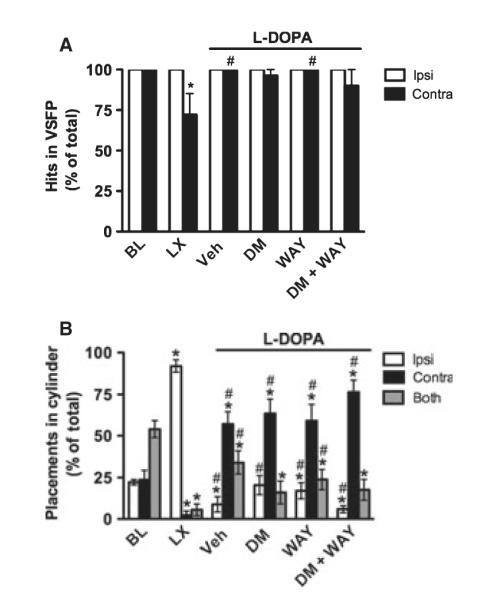

Experiment 1: amantadine in Wistar rats

VSFP

At baseline, rats showed no limb use asymmetry, as indicated by a non-significant effect of limb in the amantadine + WAY and amantadine + DCS experiments (Wilcoxon, P > 0.05; Fig. 4A and B). After the 6-OHDA lesion, the pattern of limb use changed, as expected. Specifically, in both experiments, the number of successful contralateral limb placements (‘hits’) decreased relative to ipsilateral limb placements and to baseline performance (Wilcoxon, P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Experiment 1. Amantadine in Wistar rats. At baseline, intact rats showed no limb use asymmetry in the VSFP test (A and B). After unilateral 6-OHDA, contralateral performance was impaired, as indicated by fewer successful placements (‘hits’). Chronic L-DOPA improved contralateral performance [see vehicle (Veh) group, A and B], and this effect reached significance in the DCS experiment (B). No effects were observed for amantadine, WAY-100635, DCS, or the combination of amantadine + WAY-100635 or DCS. At baseline, rats also showed no limb use asymmetry in the Cylinder test, preferring to use both limbs simultaneously (C and D). After unilateral 6-OHDA, they shifted to using the ipsilateral limb almost exclusively. Chronic L-DOPA treatment caused a shift to contralateral limb use (see Veh group, C and D), but placements were qualitatively different from those observed when animals were not expressing AIMs, as described in the text. Amantadine partially reversed this abnormal contralateral limb placement, but there were no clear effects of WAY-100635 alone or combined with amantadine. BL, baseline; LX, 6-OHDA lesion. *P < 0.05 relative to BL, #P < 0.05 relative to LX, +P < 0.05 relative to Veh.

After chronic L-DOPA treatment (see vehicle group in Fig. 4A and B), contralateral performance improved to control levels (Wilcoxon, P > 0.05), and ipsilateral and contralateral limb use were similar (Wilcoxon, P > 0.05). VSFP performance after chronic L-DOPA was significantly improved over performance at lesion in the amantadine + DCS experiment (Wilcoxon, P < 0.05; Fig. 4B), but not the amantadine + WAY experiment (Wilcoxon, P > 0.05; Fig. 4A). No drug effects were observed for amantadine, WAY-100635, DCS, amantadine + WAY-100635 or amantadine + DCS in either experiment (Wilcoxon, P > 0.05).

Cylinder

At baseline, intact rats showed no limb use asymmetry (Fig. 4C and D). There was an effect of limb (F > 24.62, P < 0.001), and paired t-tests showed that rats used both limbs together more than either the ipsilateral or the contralateral limb alone (t ≥ −4.38, P ≤ 0.01), but ipsilateral and contralateral limb use were similar (t ≤ −0.37, P > 0.05). After the 6-OHDA lesion, the pattern of limb use changed, as expected. There was an effect of limb (F > 124.01, P < 0.001), and rats used the ipsilateral limb more than the contralateral limb or both limbs together (t ≥ 7.71, P < 0.001).

After chronic L-DOPA treatment (see vehicle group), there was a significant effect of limb (F > 39.59, P < 0.001). Rats made more placements with the contralateral limb than the ipsilateral limb or both limbs together (t ≥ 6.46, P < 0.01). However, the contralateral limb placements in dyskinetic rats were qualitatively different from the deliberate, exploratory limb placements observed at baseline and after the 6-OHDA lesion. Specifically, the contralateral placements made by dyskinetic rats were rapid, repetitive movements that resembled contralateral limb AIMs directed at the cylinder wall (see Discussion for interpretation).

Amantadine altered this pattern of behavior. The effect of limb was significant in the amantadine + WAY experiment (F2, 15 = 3.95, P < 0.05; Fig. 4C), but not in the amantadine + DCS experiment (F2, 9 = 2.57, P > 0.05; Fig. 4D). More importantly, in both experiments, animals showed similar ipsilateral and contralateral limb use (t ≤ −1.16, P > 0.05). However, the amantadine-treated group showed a large amount of variability due to the small number of animals that made placements, so these data should be interpreted with caution. WAY-100635 and DCS, alone or in combination with amantadine, had no effects on performance in this test, as these groups showed similar behavior to vehicle-treated controls.

Experiment 2: DM in Wistar rats

VSFP

At baseline, rats showed no limb use asymmetry, as indicated by a non-significant effect of limb (Wilcoxon, P > 0.05; Fig. 5A). After the 6-OHDA lesion, the pattern of limb use changed, as expected. Specifically, the number of hits with the contralateral limb decreased relative to the ipsilateral limb and relative to baseline (Wilcoxon, P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Experiment 2. Dextromethorphan in Wistar rats. Similar to Experiment 1, L-DOPA improved the 6-OHDA-induced contralateral deficit in the VSFP (A) and Cylinder tests (B). No clear effects were observed for DM, WAY-100635 or DM + WAY-100635. BL, baseline; LX, 6-OHDA lesion. *P < 0.05 relative to BL, #P < 0.05 relative to LX.

After chronic L-DOPA treatment (see vehicle group), contralateral performance improved relative to the lesion (Wilcoxon, P < 0.05), similar to baseline levels (Wilcoxon, P > 0.05), and limb asymmetry was no longer apparent (Wilcoxon, P > 0.05). No drug effects were observed for DM, WAY-100635, DCS, DM + WAY-100635 or DM + DCS (Wilcoxon, P > 0.05).

Cylinder

At baseline, intact rats showed no limb use asymmetry (Fig. 5B). There was an effect of limb (F1.19,9.01 = 25.17, P < 0.001), and paired t-tests showed that rats used both limbs together more than either the ipsilateral or the contralateral limb alone (t8 ≥ −4.38, P ≤ 0.01), but there was no difference in ipsilateral vs. contralateral limb use (t8 = −0.37, P > 0.05). After the 6-OHDA lesion, the pattern of limb use changed, as expected. There was an effect of limb (F2,16 = 369.91, P < 0.001), and rats used the ipsilateral limb more than the contralateral limb or both limbs together (t8 ≥ 18.97, P < 0.001).

After chronic L-DOPA treatment (see vehicle group), there was a significant effect of limb (F2,16 = 16.78, P < 0.001). Rats made more placements with the contralateral limb than the ipsilateral limb or both limbs together (t8 ≥ 3.19, P < 0.05), but these were not normal placements, as previously described (see Discussion). No drug effects were observed for DM, WAY-100635 or DM + WAY-100635.

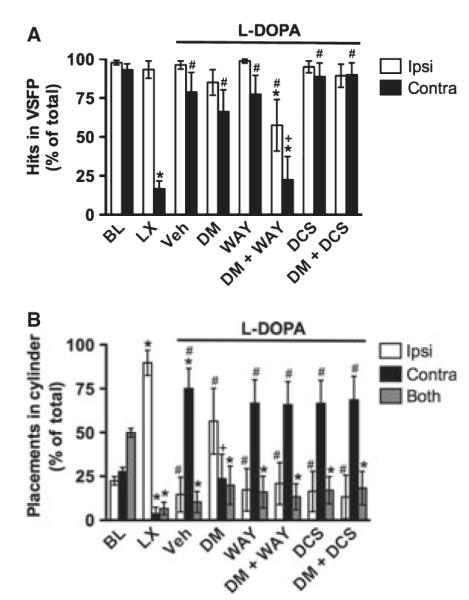

Experiment 3: DM in Sprague–Dawley rats

VSFP

At baseline, rats showed no limb use asymmetry, as indicated by a non-significant effect of limb (t8 = 1.20, P > 0.05; Fig. 6A). After the 6-OHDA lesion, the pattern of limb use changed, as expected. Specifically, the number of successful placements (‘hits’) with the contralateral limb decreased relative to the ipsilateral limb and to baseline (t8 ≥ 11.15, P < 0.001).

Fig. 6.

Experiment 3. Dextromethorphan in Sprague–Dawley rats. Similar to the effects observed in Wistar rats in Experiment 2, chronic L-DOPA improved contralateral performance in the VSFP test (A). Neither DM nor WAY-100635 affected VSFP performance relative to vehicle, but DM + WAY-100635 impaired performance of both limbs. DCS alone or combined with DM had no effect on VSFP. Also similar to Wistar rats, 6-OHDA impaired contralateral placements in the Cylinder test, and chronic L-DOPA induced abnormal contralateral placements, as described in the text (B). DM partially reversed this abnormal contralateral limb placement. While WAY-100635 and DCS had no effect alone, either drug blocked the effects of DM to make behavior similar to that of vehicle (Veh)-treated rats (compare DM + WAY-100635 and DM + DCS to DM alone). *P < 0.05 relative to BL, #P < 0.05 relative to LX, +P < 0.05 relative to Veh.

After chronic L-DOPA, contralateral performance improved relative to the lesion (t8 = 5.31, P ≤ 0.001), similar to baseline levels (t8 = 0.91, P > 0.05), and limb asymmetry was no longer apparent (t8 = −1.41, P > 0.05). DM or WAY-100635 alone had no effect on VSFP performance, but their combination significantly worsened performance. Specifically, the DM + WAY-100635 group showed fewer contralateral hits relative to baseline and to vehicle controls (t7 ≥ 3.59, P < 0.01) and fewer ipsilateral hits relative to baseline and animals tested after the 6-OHDA lesion (t7 ≥ 2.41, P < 0.05), as well as a statistical trend for fewer ipsilateral hits relative to vehicle controls (t7 = 2.27, P = 0.057). DCS alone or combined with DM had no effect on VSFP performance, as these groups were similar to controls (t7 ≥ 1.46, P > 0.05).

Cylinder

At baseline, intact rats showed no limb use asymmetry (Fig. 6B). There was an effect of limb (F2,16 = 23.95, P < 0.001), and paired t-tests showed that rats used both limbs together more than either the ipsilateral or the contralateral limb alone (t8 ≥ −5.20, P ≤ 0.001), but there was no difference in ipsilateral vs. contralateral limb use (t8 = 1.29, P > 0.05). After the 6-OHDA lesion, the pattern of limb use changed, as expected. There was an effect of limb (F1.03,8.23 = 60.58, P < 0.001), and rats used the ipsilateral limb more than the contralateral limb or both limbs together (t8 ≥ 7.71, P < 0.001).

After chronic L-DOPA treatment (see vehicle group), there was a significant effect of limb (F2,16 = 11.10, P ≤ 0.001). Rats made more placements with the contralateral limb than the ipsilateral limb or both limbs together (t8 ≥ 3.31, P ≤ 0.01), but these were not normal placements (see Discussion).

DM altered this pattern of behavior such that animals no longer showed a limb use asymmetry (F2,14 = 0.85, P > 0.05). Specifically, paired t-tests revealed that DM suppressed contralateral limb placements relative to vehicle (t8 = 2.85, P < 0.05), and the only difference from baseline performance was a reduction in the use of both limbs together (t7 = 2.61, P < 0.05). WAY-100635 by itself had no effect on limb use in the Cylinder test, as indicated by a significant effect of limb (F2,16 = 4.97, P < 0.05) and more placements with the contralateral limb than the ipsilateral or both limbs (t8 ≥ 2.32, P < 0.05), similar to vehicle-treated controls. Interestingly, rats treated with DM + WAY-100635 also showed a similar pattern of behavior to vehicle-treated animals, as indicated by a significant effect of limb (F2,14 = 4.33, P < 0.05) and more use of the contralateral limb than both limbs (t8 = 2.97, P < 0.05). DCS by itself had no effect on limb use in the Cylinder test, as indicated by a significant effect of limb (F2,14 = 4.35, P < 0.05) and greater use of the contralateral limb than both limbs (t7 = 2.53, P < 0.05) with a statistical trend for greater use than the ipsilateral limb as well (t7 = 2.29, P = 0.056). Rats treated with DM + DCS showed a similar pattern of behavior to vehicle-treated animals, as indicated by a significant effect of limb (F2,14 = 4.49, P < 0.05) and greater use of the contralateral limb than both limbs (t7 = 2.70, P < 0.05) with a statistical trend for greater use than the ipsilateral limb as well (t7 = 2.29, P = 0.071).

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to determine whether the AIM-suppressing effects of amantadine and DM (Paquette et al., 2008) involve 5-HT1A agonism or NMDA antagonism. Our data show that the AIM-suppressing effect of amantadine was sensitive to the NMDA agonist DCS but not the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100635. Conversely, the AIM-suppressing effect of DM was sensitive to WAY-100635 but not to DCS.

Amantadine has long been thought to suppress AIMs via NMDA antagonism, and our data support this mechanism of action. However, as DCS only partially prevented its antidyskinesia effect, amantadine may also act via other mechanisms, which seem unlikely to include 5-HT1A. Shearman et al. (2006) showed that treatment of rats with amantadine (20 mg/kg, s.c. or i.p.) affected extracellular neurotransmitter concentrations in a region-specific manner, including DA, norepinephrine, 5-HT, acetylcholine and their metabolites in cortical and limbic regions. These effects may be at least partially explained by changes in reuptake and turnover, as Onogi et al. (2009) demonstrated that amantadine (1 mm) inhibited monoamine oxidase-A and -B in mouse forebrain homogenates and inhibited DA and 5-HT uptake from mouse forebrain synaptosomes. Amantadine is also well known to have antiviral effects, although it seems unlikely that this would explain its antidyskinesia activity.

On the other hand, DM is believed to increase 5-HT overflow (Gaikwad et al., 2005) via inhibition of the 5-HT reuptake protein (Meoni et al., 1997; Werling et al., 2007), but it does not bind to the 5-HT1A receptor directly (Werling et al., 2007). We therefore conclude that this clinically effective antidyskinesia treatment, previously thought to act via NMDA antagonism (Verhagen Metman et al., 1998a,b,d), instead suppresses AIMs via indirect 5-HT1A agonism, similar to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (Iravani et al., 2003; Bishop et al., 2006) and fenfluramine (Bishop et al., 2006). Unfortunately, DM is not a good candidate for antidyskinesia pharmacotherapy in humans due to its potential for misuse and ability to induce psychosis at high doses, especially in vulnerable elderly patients, similar to phencyclidine and ketamine (for a review, see Miller, 2005). However, the knowledge that 5-HT1A agonism underlies the AIM-suppressing effect of DM supports exploration of selective 5-HT1A agonists for LID in PD patients.

While the antidyskinesia effects of 5-HT1A agonists are clear, the ability of these compounds to exacerbate parkinsonism, probably due to D2 antagonism or other non-selective effects, has raised concerns (Iravani et al., 2006). Furthermore, the current data replicate our recent finding that DM (45 mg/kg) suppresses L-DOPA-induced rotation (Paquette et al., 2008), which could indicate a general motor suppressing effect. This same dose of DM has been previously shown to elicit 5-HT syndrome in rats (Gaikwad et al., 2005). These factors could interfere with expression of AIMs and/or worsen PD symptoms. Although this seems unlikely given the promising clinical data (Verhagen Metman et al., 1998a,b,d), the current studies included sensorimotor assessment to investigate whether DM reduces the therapeutic effects of L-DOPA.

Using the VSFP and Cylinder tests, we demonstrated that DM does not prevent the therapeutic effects of L-DOPA in the 6-OHDA rat. It is interesting to note that, in the VSFP test, WAY-100635 had no effect on sensorimotor performance, but WAY-100635 + DM impaired performance. This suggests that the 5-HT1A agonist effects of DM mask other mechanisms of this compound that could impair sensorimotor function, such as NMDA antagonism. Over the first few days of L-DOPA treatment, 6-OHDA rats showed gradual improvement in limb asymmetry in the Cylinder test (data not shown), but after longer treatment periods such as those used in the current study, performance in the Cylinder test was confounded by L-DOPA-induced contralateral rotation and axial dystonia. Rats displayed rapid contralateral limb placements similar to limb AIMs that were interrupted to direct the limb at the cylinder wall. We observed similar placements in the VSFP test, in which rats engaged in limb AIMs until their vibrissae were brought into contact with the table-top, at which point they exhibited a rapid, purposeful placement of the dyskinetic paw on the table-top before returning to limb AIMs. In the Cylinder test, such placements may represent behavioral compensation for the effects of L-DOPA treatment, including rapid contralateral rotation, as well as the awkward posturing and falls associated with axial dystonia. In these animals, DM improves performance to baseline levels by suppressing AIMs and allowing rats to utilize both limbs in an exploratory fashion, similar to intact animals. Similarly, we have observed that unilateral 6-OHDA-treated rats show exclusive use of the contralateral limb in the Cylinder test after low-dose apomorphine (0.05 mg/kg; C. K. Meshul, unpublished data). Unilateral intrastriatal injection of an NMDA agonist in an intact rat is known to cause contralateral turning (Black et al., 1994), which suggests greater DA receptor stimulation in the drug-infused hemisphere, according to the Ungerstedt model (Ungerstedt, 1971). Similarly, DM and DCS may have augmented DAergic function in the lesioned hemisphere of our 6-OHDA rats to improve performance in the Cylinder test.

Clearly, inclusion of sensorimotor assessment in animal models is imperative to ensure that putative antidyskinesia drugs are not translated into clinical trials if they exacerbate parkinsonism, as was the case with sarizotan (Olanow et al., 2004; Goetz et al., 2007). The clinical development of sarizotan was predicated on preclinical studies that lacked measures of therapeutic efficacy. In light of this translational failure, preclinical researchers are now including such measures. Some examples include: VSFP (Lindner et al., 1996; Monville et al., 2005; Paquette et al., 2010), Cylinder (Lundblad et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2009a,b; Paquette et al., 2010; Riddle et al., 2011), Adjusting Steps (Winkler et al., 2002; Eskow et al., 2007, 2009; Paillé et al., 2007) and Rotarod (Dekundy et al., 2007).

Sensorimotor data from animals with L-DOPA-induced AIMs need to be interpreted with caution. For example, in the Cylinder test, the shift from ipsilateral limb use after 6-OHDA to contralateral limb use after L-DOPA treatment could be interpreted as a striking therapeutic effect of L-DOPA. However, upon closer inspection, performance of severely dyskinetic rats in the Cylinder test appears to be confounded by AIMs, such that rats either cannot perform the task (Carta et al., 2007), or limb AIMs result in an increased number of rapid, repetitive contralateral placements (current study). Other behavioral tests may also be confounded by AIMs. For example, Winkler et al. (2002) found that chronic L-DOPA treatment impaired performance in the Montoya staircase, which requires skilled forelimb reaching and grasping. This impairment may be due to limb AIMs interfering with skilled reaching behavior. Another consideration is that different behavioral tests may measure different components of behavior (Paquette et al., 2009b). For example, VSFP assesses the ability to use each forelimb individually, while the Cylinder test assesses the preference for forelimb use. Thus, careful selection and interpretation of sensorimotor tests are crucial in studies of L-DOPA-induced AIMs, and inclusion of multiple sensorimotor tests is recommended.

It is interesting that amantadine suppressed AIMs in Wistar but not Sprague–Dawley rats. This could be partially explained by strain-dependent differences in the expression of AIMs. For example, Wistar rats expressed more severe axial and oral AIMs and were more likely to remain in a prone position, licking and/or biting the contralateral limb or shoulder. Conversely, Sprague–Dawley rats expressed more severe L-DOPA-induced rotation. Overall, Sprague–Dawley rats had higher levels of AIMs, although whether this difference was statistically significant could not be determined, as the two strains were not tested concurrently. Methodological differences in the lesion procedure (i.e. coordinates, number of sites and amount of 6-OHDA infused) and L-DOPA treatment regimen might have contributed to the strain differences observed. Finally, we found that the amantadine-induced suppression of AIMs in Wistar rats decreased over repeated treatments, similar to the loss of efficacy observed over time in PD patients. We suggest that the antidyskinesia effects of amantadine in rats may be relatively weak and may only be apparent in animals expressing lower levels of AIMs, and we believe that future studies to directly test this hypothesis are warranted.

The current data add to the growing body of literature supporting a role for the 5-HTergic system in LID. 5-HT neurons can synthesize and release DA from exogenous L-DOPA, and 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine lesions decrease striatal DA overflow (Tanaka et al., 1999) and prevent AIMs development (Eskow et al., 2009) and expression (Carta et al., 2007). 5-HT1A receptors are known to be upregulated in the striatum in animal models of PD (Frechilla et al., 2001), and 5-HT1A agonists have been shown to affect midbrain DAergic activity (Kelland et al., 1990; Cobb & Abercrombie, 2003), reduce L-DOPA-mediated DA overflow in striatum (Kannari et al., 2000) and suppress AIMs after intra-raphe (Eskow et al., 2009) or systemic administration (Lundblad et al., 2002, 2005; Tomiyama et al., 2005; Iravani et al., 2006; Carta et al., 2007; Dekundy et al., 2007; Dupre et al., 2007, 2008; Eskow et al., 2007; Paquette et al., 2009a). In support of the predictive validity of these animal models, LID in human PD patients is also suppressed by 5-HT1A agonists (Bonifati et al., 1994; Kannari et al., 2002; Olanow et al., 2004; Goetz et al., 2007).

It has been proposed that dyskinesia results when striatal 5-HTergic terminals release DA as a false neurotransmitter, resulting in supraphysiological stimulation of DA receptors (Carta et al., 2007). According to this theory, 5-HT1A agonists stimulate autoreceptors to dampen DA release, thus suppressing AIMs. The current data are consistent with this theory, as DM is thought to cause neurotransmitter overflow from 5-HTergic terminals (Gaikwad et al., 2005). In rats expressing AIMs, we speculate that DM may cause overflow of both 5-HT and DA from 5-HTergic terminals. The subsequent 5-HTergic stimulation of 5-HT1A autoreceptors provides a mechanism for regulating DA overflow, which thereby suppresses AIMs. Conversely, co-administration of DM with the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100635 should prevent this regulation, thus allowing AIMs to be expressed.

We previously demonstrated that the AIM-suppressing effect of the sigma-1 antagonist BMY-14802 in the 6-OHDA rat model of PD (Paquette et al., 2008, 2009a) was sensitive to 5-HT1A antagonism (Paquette et al., 2009a). We now show that the AIM-suppressing effect of DM has a similar sensitivity to a 5-HT1A antagonist. Furthermore, using tests of sensorimotor function, we show that DM does not prevent the therapeutic effects of L-DOPA. Unfortunately, DM is not a good candidate for antidyskinesia pharmacotherapy in humans (Miller, 2005). However, our data make a compelling case that selective 5-HT1A agonists merit further preclinical study and clinical evaluation as treatments for LID.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by NINDS NS38715 (S.W.J.), the Portland VA Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education, and Clinical Center (S.W.J.), Veterans Affairs Merit Review grants (C.K.M. and S.P.B.), NINDS/5NS050401 (A.G.) and the San Antonio Area Foundation (M.P.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- AIMs

abnormal involuntary movements

- ALO

axial + limb + oral

- DA

dopamine

- DCS

d-cycloserine

- DM

dextromethorphan

- L-DOPA

levodopa

- LID

L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- UTHSCSA

University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio

- VAMC

Veterans Affairs Medical Center

- VSFP

Vibrissae-Stimulated Forelimb Placement

- 5-HT

serotonin

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

References

- Baptista T, López ME, Teneud L, Contreras Q, Alastre T, de Quijada M, Araujo de Baptista E, Alternus M, Weiss SR, Musseo E, Páez X, Hernández L. Amantadine in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced obesity in rats: behavioral, endocrine and neurochemical correlates. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1997;30:43–54. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop C, Taylor JL, Kuhn DM, Eskow KL, Park JY, Walker PD. MDMA and fenfluramine reduce L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia via indirect 5-HT1A receptor stimulation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:2669–2676. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MD, Crossman AR, Hayes AG, Elliott PJ. Acute and chronic behavioural sequelae resulting from intrastriatal injection of an NMDA agonist. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1994;48:441–446. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet PJ, Papa SM, Metman LV, Mouradian MM, Chase TN. Modulation of levodopa-induced motor response complications by NMDA antagonists in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1997;21:447–453. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifati V, Fabrizio E, Cipriani R, Vanacore N, Meco G. Buspirone in levodopa-induced dyskinesias. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 1994;17:73–82. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199402000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson T, Carta M, Winkler C, Björklund A, Kirik D. Serotonin neuron transplants exacerbate L-DOPA-induced dyskinesias in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:8011–8022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2079-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta M, Lindgren HS, Lundblad M, Stancampiano R, Fadda F, Cenci MA. Role of striatal L-DOPA in the production of dyskinesia in 6-hydroxydopamine lesioned rats. J. Neurochem. 2006;96:1718–1727. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta M, Carlsson T, Kirik D, Björklund A. Dopamine released from 5-HT terminals is the cause of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in parkinsonian rats. Brain. 2007;130:1819–1833. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenci MA, Lee CS, Björklund A. L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in the rat is associated with striatal overexpression of prodynorphin- and glutamic acid decarboxylase mRNA. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998;10:2694–2706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JW, Wachtel SR, Young D, Kang UJ. Biochemical and anatomical characterization of forepaw adjusting steps in rat models of Parkinson’s disease: studies on medial forebrain bundle and striatal lesions. Neuroscience. 1999;88:612–628. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase TN, Oh JD, Konitsiotis S. Antiparkinsonian and antidyskinetic activity of drugs targeting central glutamatergic mechanisms. J. Neurol. 2000;247(Suppl. 2):II36–II42. doi: 10.1007/pl00007759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church J, Sawyer D, McLarnon JG. Interactions of dextromethorphan with the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-channel complex: single channel recordings. Brain Res. 1994;666:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90771-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb WS, Abercrombie ED. Differential regulation of somatodendritic and nerve terminal dopamine release by serotonergic innervation of substantia nigra. J. Neurochem. 2003;84:576–584. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekundy A, Lundblad M, Danysz W, Cenci MA. Modulation of L-DOPA-induced abnormal involuntary movements by clinically tested compounds. Behav. Brain Res. 2007;179:76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Dotto P, Pavese N, Gambaccini G, Bernardini S, Metman LV, Chase TN, Bonuccelli U. Intravenous amantadine improves levadopa-induced dyskinesias: an acute double-blind placebo-controlled study. Mov. Disord. 2001;16:515–520. doi: 10.1002/mds.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depoortere R, Perrault G, Sanger DJ. Prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex in rats: effects of compounds acting at various sites on the NMDA receptor complex. Behav. Pharmacol. 1999;10:51–62. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199902000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupre KB, Eskow KL, Negron G, Bishop C. The differential effects of 5-HT (1A) receptor stimulation on dopamine receptor-mediated abnormal involuntary movements and rotations in the primed hemiparkinsonian rat. Brain Res. 2007;1158:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupre KB, Eskow KL, Steiniger A, Klioueva A, Negron GE, Lormand L, Park JY, Bishop C. Effects of coincident 5-HT(1A) receptor stimulation and NMDA receptor antagonism on L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia and rotational behaviors in the hemi-parkinsonian rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskow KL, Gupta V, Alam S, Park JY, Bishop C. The partial 5-HT(1A) agonist buspirone reduces the expression and development of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in rats and improves L-DOPA efficacy. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2007;87:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskow KL, Dupre KB, Barnum CJ, Dickinson SO, Park JY, Bishop C. The role of the dorsal raphe nucleus in the development, expression, and treatment of L-dopa-induced dyskinesia in hemiparkinsonian rats. Synapse. 2009;63:610–620. doi: 10.1002/syn.20630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frechilla D, Cobreros A, Saldise L, Moratalla R, Insausti R, Luquin M, Del Río J. Serotonin 5-HT(1A) receptor expression is selectively enhanced in the striosomal compartment of chronic parkinsonian monkeys. Synapse. 2001;39:288–296. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010315)39:4<288::AID-SYN1011>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaikwad RV, Gaonkar RK, Jadhav SA, Thorat VM, Jadhav JH, Balsara JJ. Involvement of central serotonergic systems in dextromethorphan-induced behavioural syndrome in rats. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2005;43:620–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz CG, Damier P, Hicking C, Laska E, Müller T, Olanow CW, Rascol O, Russ H. Sarizotan as a treatment for dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Mov. Disord. 2007;22:179–186. doi: 10.1002/mds.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iravani MM, Jackson MJ, Kuoppamäki M, Smith LA, Jenner P. 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy) inhibits dyskinesia expression and normalizes motor activity in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-treated primates. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:9107–9115. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09107.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iravani MM, Tayarani-Binazir K, Chu WB, Jackson MJ, Jenner P. In 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-treated primates, the selective 5-hydroxytryptamine 1A agonist (R)-(+)-8-OHDPAT inhibits levodopa-induced dyskinesia but only with increased motor disability. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;319:1225–1234. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamei J. Role of opioidergic and serotonergic mechanisms in cough and antitussives. Pulm. Pharmacol. 1996;9:349–356. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1996.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamei J, Mori T, Igarashi H, Kasuya Y. Effects of 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin, a selective agonist of 5-HT1A receptors, on the cough reflex in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;203:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannari K, Tanaka H, Maeda T, Tomiyama M, Suda T, Matsunaga M. Reserpine pretreatment prevents increases in extracellular striatal dopamine following l-DOPA administration in rats with nigrostriatal denervation. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:263–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannari K, Kurahashi K, Tomiyama M, Maeda T, Arai A, Baba M, Suda T, Matsunaga M. Tandospirone citrate, a selective 5-HT1A agonist, alleviates L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. No To Shinkei. 2002;54:133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelland MD, Freeman AS, Chiodo LA. Serotonergic afferent regulation of the basic physiology and pharmacological responsiveness of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;253:803–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornhuber J, Bormann J, Hübers M, Rusche K, Riederer P. Effects of the 1-amino-adamantanes at the MK-801-binding site of the NMDA-receptor-gated ion channel: a human postmortem brain study. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;25:297–300. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(91)90113-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Riddle LR, Griffin SA, Chu W, Vangveravong S, Neisewander J, Mach RH, Luedtke RR. Evaluation of D2 and D3 dopamine receptor selective compounds on L-dopa-dependent abnormal involuntary movements in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2009a;56:956–969. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Riddle L, Griffin SA, Grundt P, Newman AH, Luedtke RR. Evaluation of the D3 dopamine receptor selective antagonist PG01037 on L-dopa-dependent abnormal involuntary movements in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2009b;56:944–955. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren HS, Andersson DR, Lagerkvist S, Nissbrandt H, Cenci MA. L-DOPA-induced dopamine efflux in the striatum and the substantia nigra in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease: temporal and quantitative relationship to the expression of dyskinesia. J. Neurochem. 2010;112:1465–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner MD, Plone MA, Francis JM, Emerich DF. Validation of a rodent model of Parkinson’s Disease: evidence of a therapeutic window for oral Sinemet. Brain Res. Bull. 1996;39:367–372. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(96)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad M, Andersson M, Winkler C, Kirik D, Wierup N, Cenci MA. Pharmacological validation of behavioural measures of akinesia and dyskinesia in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002;15:120–132. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad M, Usiello A, Carta M, Hkanssond K, Fisoned G, Cenci MA. Pharmacological validation of a mouse model of l-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Exp. Neurol. 2005;194:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin C, Jimenez A, Bonastre M, Chase TN, Tolosa E. Non-NMDA receptor-mediated mechanisms are involved in levodopa-induced motor response alterations in Parkinsonian rats. Synapse. 2000;36:267–274. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(20000615)36:4<267::AID-SYN3>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mela F, Marti M, Bido S, Cenci MA, Morari M. In vivo evidence for a differential contribution of striatal and nigral D1 and D2 receptors to L-DOPA induced dyskinesia and the accompanying surge of nigral amino acid levels. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012;45:573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meoni P, Tortella FC, Bowery NG. An autoradiographic study of dextromethorphan high-affinity binding sites in rat brain: sodium-dependency and colocalization with paroxetine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:1255–1262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metman LV, Del Dotto P, LePoole K, Konitsiotis S, Fang J, Chase TN. Amantadine for levodopa-induced dyskinesias: a 1-year followup study. Arch. Neurol. 1999;56:1383–1386. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.11.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SC. Dextromethorphan psychosis, dependence and physical withdrawal. Addict. Biol. 2005;10:325–327. doi: 10.1080/13556210500352410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monville C, Torres EM, Dunnett SB. Validation of the l-dopa-induced dyskinesia in the 6-OHDA model and evaluation of the effects of selective dopamine receptor agonists and antagonists. Brain Res. Bull. 2005;68:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moregese MG, Cassano T, Cuomo V, Giuffrida A. Anti-dyskinetic effects of cannabinoids in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease: role of CB(1) and TRPV1 receptors. Exp. Neurol. 2007;208:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moregese MG, Cassano T, Gaetani S, Macheda T, Laconca L, Dipasquale P, Ferraro L, Antonelli T, Cuomo V, Giuffrida A. Neurochemical changes in the striatum of dyskinetic rats after administration of the cannabinoid agonist WIN55,212-2. Neurochem. Int. 2009;54:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzer R, Pflimlin P, Trube G. Dextromethorphan blocks N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced currents and voltage-operated inward currents in cultured cortical neurons. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;238:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90849-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olanow CW, Damier P, Goetz CG, Mueller T, Nutt J, Rascol O, Serbanescu A, Deckers F, Russ H. Multicenter, open-label, trial of sarizotan in Parkinson disease patients with levodopa-induced dyskinesias: the SPLENDID Study. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2004;27:58–62. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200403000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onogi H, Ishigaki S, Nakagawasai O, Arai-Kato Y, Arai Y, Watanabe H, Miyamoto A, Tan-no K, Tadano T. Influence of memantine on brain monoaminergic neurotransmission parameters in mice: neurochemical and behavioral study. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009;32:850–855. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillé V, Henry V, Lescaudron L, Brachet P, Damier P. Rat model of Parkinson’s disease with bilateral motor abnormalities, reversible with levodopa, and dyskinesias. Mov. Disord. 2007;22:533–539. doi: 10.1002/mds.21308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette MA, Brudney EG, Putterman DB, Meshul CK, Johnson SW, Berger SP. Sigma ligands, but not N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists, reduce levodopa-induced dyskinesias. NeuroReport. 2008;19:111–115. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f3b0d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette MA, Foley K, Brudney EG, Meshul CK, Johnson SW, Berger SP. The sigma-1 antagonist BMY-14802 inhibits L-DOPA-induced abnormal involuntary movements by a WAY-100635-sensitive mechanism. Psychopharmacology. 2009a;204:743–754. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1505-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette MA, Marsh ST, Hutchings JE, Castañeda E. Amphetamine-evoked rotation requires newly-synthesized dopamine at 14 days but not 1 day after intranigral 6-OHDA and is consistently dissociated from sensorimotor behavior. Behav. Brain Res. 2009b;200:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette MA, Anderson AM, Lewis JR, Meshul CK, Johnson SW, Berger SP. MK-801 inhibits L-DOPA-induced abnormal involuntary movements only at doses that worsen parkinsonism. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:1002–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons CG, Quack G, Bresink I, Baran L, Przegalinski E, Kostowski W, Krzascik P, Hartmann S, Danysz W. Comparison of the potency, kinetics and voltage-dependency of a series of uncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonists in vitro with anticonvulsive and motor impairment activity in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1239–1258. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00092-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle LR, Kumar R, Griffin SA, Grundt P, Newman AH, Luedtke RR. Evaluation of the D3 dopamine receptor selective agonist/partial agonist PG01042 on L-dopa dependent animal involuntary movements in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rylander D, Parent M, O’Sullivan SS, Dovero S, Lees AJ, Bezard E, Descarries L, Cenci MA. Maladaptive plasticity of serotonin axon terminals in levodopa-induced dyskinesia. Ann. Neurol. 2010;68:619–628. doi: 10.1002/ana.22097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallert T, Fleming SM, Leasure JL, Tillerson JL, Bland ST. CNS plasticity and assessment of forelimb sensorimotor outcome in unilateral rat models of stroke, cortical ablation, parkinsonism and spinal cord injury. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:777–787. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearman E, Rossi S, Szasz B, Juranyi Z, Fallon S, Pomara N, Sershen H, Lajtha A. Changes in cerebral neurotransmitters and metabolites induced by acute donepezil and memantine administrations: a microdialysis study. Brain Res. Bull. 2006;69:204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sills MA, Loo PS. Tricyclic antidepressants and dextromethorphan bind with higher affinity to the phencyclidine receptor in the absence of magnesium and L-glutamate. Mol. Pharmacol. 1989;36:160–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Kannari K, Maeda T, Tomiyama M, Suda T, Matsunaga M. Role of serotonergic neurons in l-DOPA-derived extracellular dopamine in the striatum of 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. NeuroReport. 1999;10:631–634. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199902250-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama M, Kimura T, Maeda T, Kannari K, Matsunaga M, Baba M. A serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonist prevents behavioral sensitization to L-DOPA in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Res. 2005;52:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerstedt U. Striatal dopamine release after amphetamine or nerve degeneration revealed by rotational behaviour. Acta Physiol. Scand. Suppl. 1971;367:49–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1971.tb10999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen Metman L, Blanchet PJ, van den Munckhof P, Del Dotto P, Natté R, Chase TN. A trial of dextromethorphan in parkinsonian patients with motor response complications. Mov. Disord. 1998a;13:414–417. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen Metman L, Del Dotto P, van den Munckhof P, Fang J, Mouradian MM, Chase TN. Amantadine as treatment for dyskinesias and motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1998b;50:1323–1326. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen Metman L, Del Dotto P, Natté R, van den Munckhof P, Chase TN. Dextromethorphan improves levodopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1998c;51:203–206. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen Metman L, Del Dotto P, Blanchet PJ, van den Munckhof P, Chase TN. Blockade of glutamatergic transmission as treatment for dyskinesias and motor fluctuations in PD. Amino Acids. 1998b;14:75–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01345246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Ressler KJ, Lu KT, Davis M. Facilitation of conditioned fear extinction by systemic administration or intra-amygdala infusions of D-cycloserine as assessed with fear-potentiated startle in rats. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:2343–2351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02343.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, Nuwayhid SJ. A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder. Exp. Neurol. 2007;207:248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler C, Kirik D, Björklund A, Cenci MA. L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in the intrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson’s disease: relation to motor and cellular parameters of nigrostriatal function. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;10:165–186. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]