Abstract

Catatonia, originally described by Karl Kahlbaum in 1874, may be regarded as a set of clinical features found in a subtype of schizophrenia, but the syndrome may also stem from organic causes including vascular parkinsonism, brain masses, globus pallidus lesions, metabolic derangements, and pharmacologic agents, especially first generation antipsychotics. Catatonia may include paratonia, waxy flexibility (cerea flexibilitas), stupor, mutism, echolalia, and catalepsy (abnormal posturing). A case of catatonia as a result of acute renal failure in a patient with dementia with Lewy bodies is described. This patient recovered after intravenous fluid administration and reinstitution of the atypical dopamine receptor blocking agent quetiapine, but benzodiazepines and amantadine are additional possible treatments. Recognition of organic causes of catatonia leads to timely treatment and resolution of the syndrome.

Key words: Dementia with Lewy bodies, Catatonia, Catalepsy

Introduction

Catatonia may be regarded as a set of clinical features found in a subtype of schizophrenia, but the syndrome may also stem from organic causes including vascular parkinsonism, brain masses, globus pallidus lesions, metabolic derangements, and pharmacologic agents, especially first generation antipsychotics [1]. Catatonia may include catalepsy (abnormal posturing), waxy flexibility (cerea flexibilitas), mitgehen (facilitatory paratonia), gegenhalten (negativism or oppositional paratonia), stereotypic behavior, stupor, mutism, and echolalia. Clinical features of catatonia were originally described by Karl Kahlbaum in 1874 with emphasis on strong association with affective disorders – depression and mania [2]. A case of catatonia as a result of acute renal failure in a patient with dementia with Lewy bodies is described.

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old female with a history of dementia with Lewy bodies and chronic renal insufficiency presented with a 5-day history of decreased oral intake and vomiting 2–3 times per day as well as progressively decreasing responsiveness. On initial evaluation, the patient displayed echolalia for one to two syllable words, but was otherwise mute. She did not follow verbal commands, kept her eyes closed and resisted attempts to open her eyelids. She was not able to follow any verbal commands. The patient had no tremor, but moderate lower extremity rigidity bilaterally. There was mitgehen (facilitatory paratonia) in the bilateral upper extremities, with the patient actively assisting the examiner's movements. She displayed catalepsy via maintenance of abnormal postures in bilateral upper extremities. There were no upper motor neuron signs. The patient also displayed a 10-second period of stereotypically grasping the bed sheet with both hands.

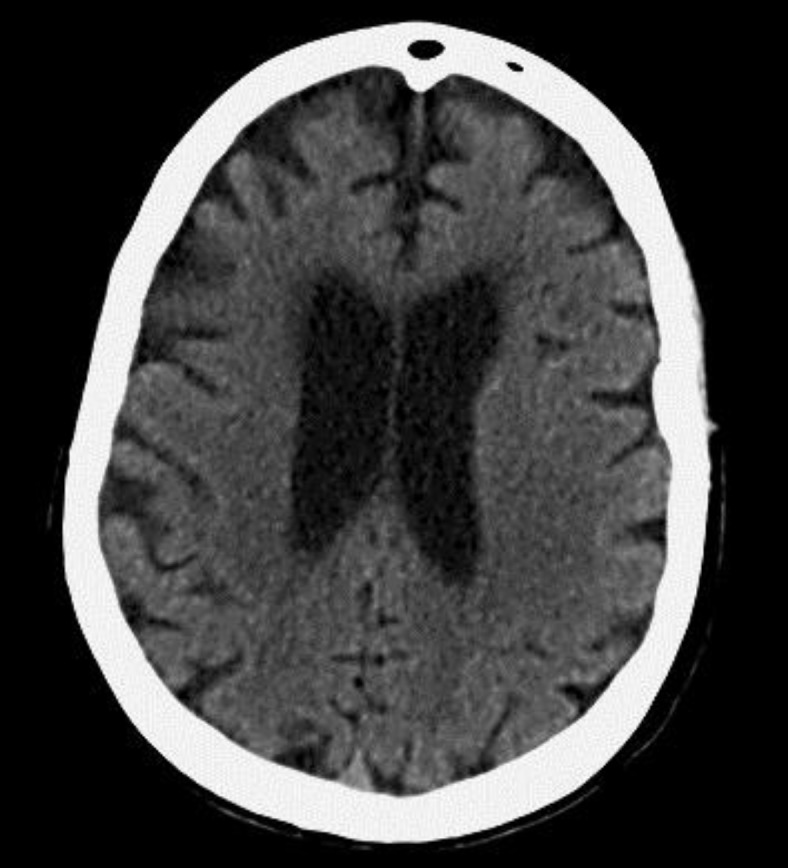

A CT of the head showed generalized cortical atrophy (fig. 1). Laboratory studies revealed acute renal failure with creatinine of 2.38 mg/dl and bacteriuria with positive nitrites but absent leukocyte esterase. She was treated with intravenous saline and creatinine improved to 1.52 mg/dl on day 3 and 1.41 mg/dl on day 4. Her quetiapine 50-mg each evening doses were held on the first two hospital nights. Quetiapine was restarted at 25 mg in the evening on the third hospital night.

Fig. 1.

Axial CT of the head showing widened sulci and narrowed gyri due to generalized atrophy.

On hospital day 4, she was alert to voice. She opened her eyes and slowly followed a one-step command to show a thumbs up sign with the right hand. Upper extremity mitgehen persisted. Catalepsy was mildly improved but still present in the upper extremities (online suppl. video, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000346594). A rare right 4th and 5th digit metacarpophalangeal joint abduction adduction rest and postural tremor were seen in the right hand on this day. Her mental status recovered to baseline by day 7, and she was transferred back to an assisted living facility.

Past Medical History

She began to have cognitive problems about 2 years ago. She was diagnosed with diffuse Lewy body disease 1.5 years ago according to consensus diagnostic criteria [3] and was placed in assisted living shortly thereafter. At the time of diagnosis, she had visual hallucinations, memory difficulty, right worse than left bradykinesia, rigidity, rest, and postural tremor. She was started on levodopa therapy that was eventually escalated to two tablets of 25/100 mg 3 times daily. At current baseline in assisted living, she is alert and oriented to self and location and is able to follow two-step verbal commands. Due to hallucinations, she was started on quetiapine with a current dose of 50 mg in the evening. She also took 16-mg extended release tablets of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor galantamine daily and 10-mg tablets twice daily of N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist and the D2 dopaminergic agonist memantine. Additional medications included levothyroxine 100 μg daily for hypothyroidism, prednisone 10 mg daily for polymyalgia rheumatica, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg daily, lasix 20 mg twice daily, and losartan 50 mg daily for hypertension.

Discussion

The mechanism of the patient's acute renal failure was most likely via pre-renal azotemia due to vomiting, dehydration, and perhaps overly aggressive diuresis in the setting of chronic renal insufficiency. She improved markedly in response to intravenous fluid administration.

A wide range of organic disturbances can cause catatonia. These include metabolic disturbances as in this case, infection, non-convulsive status epilepticus, brain lesions (including vascular and mass lesions), various prescription medications, and illicit drugs [4]. Hence, a systematic evaluation including serum metabolic panel, electroencephalography, brain imaging, blood and urine cultures, and urine drug screen is helpful [4].

Clinical features of catatonia demonstrated in this case were catalepsy, mitgehen, stupor, mutism, stereotypies, and echolalia. Catalepsy is currently defined as abnormal posturing or maintenance of uncomfortable body positions, which in extreme cases can extend to maintaining the ‘crucifix’ or even ‘psychological pillow’ positions [4]. Julien de La Mettrie described ‘hysterical catalepsy’ in 1738 [5], in which ‘fingers, phalanges, wrists, lower, and upper arms … remain immobile, in the position in which one placed her’. A similar observation about catalepsy was made by Dionis in 1713 [5]. de La Mettrie's case also included periods of agitation that might now be described as excited catatonia [6].

Cerea flexibilitas is a peculiar clinical examination feature of catatonia. Cerea means waxy in Latin, and the complete term describes initial resistance to movement followed by flexibility similar to bending a wax candle [6]. In contrast, this patient had no initial resistance to movement and instead appeared to assist the examiner, demonstrating mitgehen (facilitatory paratonia/automatic obedience). Her arms remained suspended in midair due to catalepsy (online suppl. video).

In animal models, catalepsy testing is defined as ‘placing an animal into an unusual posture and recording the time taken to correct this posture’ [7]. Catalepsy has originally been thought to occur solely due to lack of dopamine. In fact, assays of catalepsy in laboratory animals have been used to determine the degree of nigrostriatal dopaminergic blockade for example by phenothiazine and butyrophenone neuroleptics [8]. In addition, this effect has been studied as an experimental model of Parkinson's disease in animals.

Fluphenazine and other dopamine receptor blocking agents have been reported to cause catatonia in humans [1]. The current terminology for this effect is neuroleptic-induced catatonia and leads the treating physician into the ‘catatonic dilemma’ whereby even milder second generation antipsychotics can be both a cause and treatment of catatonia [9]. This patient continued to improve on quetiapine 25 mg dosed in the evening after quetiapine was held for the first two hospital days.

A much more nuanced view of the pathophysiology of catatonia has emerged over time, with possible contribution not only by D2 dopaminergic hypoactivity, but also cholinergic and serotonergic hyperactivity, glutamate hyperactivity, and GABAA hypoactivity [9]. The picture is even more complex, as an animal study showed that serotonergic agonists may interfere with dopamine receptor antagonist-induced catalepsy [10]. Another novel theory proposes that catatonia is related to an evolutionary fear response, arising from a need to stay still to avoid being noticed by predators trained to detect movement [4], which may be especially relevant to psychiatric causes of the syndrome. Attacks of catalepsy even in de La Mettrie's case description could be triggered by ‘the tiniest scare’ [5].

In addition to correcting the underlying organic abnormality, specific treatments for catatonia are available. In light of the possible mechanisms described above, benzodiazepines and N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists such as amantadine and memantine are useful treatments [4]. Atypical antipsychotics may be helpful, but the ‘catatonic dilemma’ needs to be contemplated in each individual case. Electroconvulsive therapy may be considered in medication refractory cases [4].

In conclusion, catatonia may have both organic and psychiatric causes. Proper recognition of metabolic causes of catatonia in this case allowed for appropriate therapy and resolution of symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Video

References

- 1.Gelenberg AJ. The catatonic syndrome. Lancet. 1976;307:1339–1341. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)92669-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee YM. The Kahlbaum Syndrome is a Risk Factor for the Development of Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome. J Neurol Res. 2011;1:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKeith IG. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:144–147. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajagopal S. Catatonia. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007;vol 13:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walusinski O. A Case of Charcotian grande hystérie: observation by Julien Offray de La Mettrie in 1738. Eur Neurol. 2012;67:98–106. doi: 10.1159/000334736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fink M, Taylor MA. The catatonia syndrome: forgotten but not gone. Arch Gene Psychiatry. 2009;66:1173–1177. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanberg PR, Bunsey MD, Giordano M, Norman AB. The catalepsy test: its ups and downs. Behav Neurosci. 1988;102:748–759. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hornykiewicz O. Dopamine in the basal ganglia. Its role and therapeutic implications (including the clinical use of L-DOPA) Br Med Bull. 1973;29:172–178. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a070990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll BT, Lee JW, Appiani F, Thomas C. The pharmacotherapy of catatonia. Prim Psychiatry. 2010;17:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wadenberg ML. Serotonergic mechanisms in neuroleptic-induced catalepsy in the rat. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1996;20:325–339. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Video