Abstract

Enniatins are cyclohexadepsipeptides isolated largely from Fusarium species of fungi, although they have been isolated from other genera, such as Verticillium and Halosarpheia. They were first described over 60 years ago, and their range of biological activities, including antiinsectan, antifungal, antibiotic, and cytotoxic, drives contemporary interest. To date, 29 enniatins have been isolated and characterized, either as a single compound or mixtures of inseparable homologs. Structurally, these depsipeptides are biosynthesized by a multifunctional enzyme, termed enniatin synthetase, and are composed of six residues that alternate between N-methyl amino acids and hydroxy acids. Their structure elucidation can be challenging, particularly for enniatins isolated as inseparable homologs; however, several strategies and tools have been utilized to solve these problems. Currently, there is one drug that has been developed from a mixture of enniatins, fusafungine, which is used as a topical treatment of upper respiratory tract infections by oral and/or nasal inhalation. Given the range of biological activities observed for this class of compounds, research on enniatins will likely continue. This review strives to digest the past studies, as well as, describe tools and techniques that can be utilized to overcome the challenges associated with the structure elucidation of mixtures of enniatin homologs.

Keywords: enniatin, Fusarium, cyclohexadepsipeptide, homolog, enniatin synthetase, hydroxyisovaleric acid

A. Introduction and History of Enniatins

Enniatins are cyclohexadepsipeptides composed of alternating residues of three N-methyl amino acids, commonly valine (Val), leucine (Leu), and isoleucine (Ile), and three hydroxy acids, typically hydroxyisovaleric acid (Hiv). These secondary metabolites have been observed frequently from Fusarium species of fungi, although they have been isolated from a few other genera, as well (Table 1). The first enniatin [enniatin A (1)] was reported from the fungus Fusarium orthoceras var. enniatinum by Gaumann et al. in 1947,1 and 1 was shown to be active against several mycobacteria in vitro. Shortly thereafter, another group working independently, isolated a compound they named lateritiin-I from Fusarium lateritium, which was found to be identical to 1.2,3 In 1974, Audhya and Russel4 identified that previously reported enniatin A was actually a mixture of threo and erythro optical isomers. At that time only enniatin B had been observed pure from a natural source.5 Scientists worked to scale up the production of enniatin A, largely for the purpose of studying its ionophoric properties, which had started to emerge as the probable mechanism of action for enniatins.5 One isolation study4,6 yielded a mixture ofenniatins A (1), A1 (3), B (2), and B1 (4), while an earlier insecticidal assay-guided study revealed that an enniatin A and A1-rich complex was the active component in a fraction toxic to spruce budworm larvae.7 However, in 1992 the first report on the purification of enniatins A (1), A1 (3), B (2), B1 (4), and new analog A2 (5),8 was published. From that point on, the isolation and characterization of enniatins expanded to include: enniatins B2 (6), B3 (7) and B4 (8)9 [D (8), which has the same structure as B4, was published in the same year]10; C (9);11 E1 (10), E2 (11) and F (12);10 G (13);12 H (14) and I (15) together with biosynthesized analogs G (13), C (9), and MK1688 (16);13 J1 (17), J2 (18), J3 (19), and K1 (20);14 L (21), M1 (22), M2 (23), and N (24);15 O1 (25), O2 (26), and O3 (27);11 and most recently, P1 (28) and P2 (29).16 Enniatin C (9) was reported first as a synthetic product,4 then as a biosynthetic product,13 before it was isolated as a natural product.11

Table 1.

Sources and bioactivities of enniatins derived from the literature.

| Enniatin | Biological Sourcea | Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|

| A (1) |

Fusarium avenaceum;50 Fusarium sp. FO-130510 |

Cytotoxic against Hep G2, MRC-5; ACAT inhibition |

| A1 (3) |

Fusarium avenaceum;50 Fusarium sp. FO-130510 |

Cytotoxic against Hep G2, MRC-5; ACAT inhibition |

| A2 (5) | Fusarium avenaceum50 | Cytotoxic against Hep G2, MRC-5 |

| B (2) |

Fusarium avenaceum;50 Fusarium sp. FO-1305;10 Verticillium hemipterigenum13 |

Cytotoxic against Hep G2, MRC-5; ACAT inhibition |

| B1 (4) |

Fusarium avenaceum;50 Fusarium sp. FO-130510 |

Cytotoxic against Hep G2, MRC-5; ACAT inhibition |

| B2 (6) |

Fusarium acuminatum9 A, A1, B, B1, B2, B4 |

Cytotoxic against Hep G2, MRC-5; |

| B3 (7) | Fusarium acuminatum9 | Cytotoxic against Hep G2, MRC-5 |

| B4 = D (8) Because both were published in 1992 |

Fusarium acuminatum;9 Fusarium sp. FO-1305;10 Verticillium hemipterigenum13 |

ACAT inhibition |

| C (9) |

Verticillium hemipterigenum13 B, B4, G, C |

Antimalarial, antituberculous, cytotoxic |

| E1 (10) | Fusarium sp. FO-130510 | ACAT inhibition |

| E2 (11) | Fusarium sp. FO-130510 | ACAT inhibition |

| F (12) | Fusarium sp. FO-130510 | ACAT inhibition |

| G (13) |

Halosarpheia sp. (strain732)12 B, B4 |

Heps 7402 |

| H (14) |

Verticillium hemipterigenum13 B, B4, G, C |

Antimalarial, antituberculous, cytotoxic |

| I (15) |

Verticillium hemipterigenum13 B, B4, G, C |

Antimalarial, antituberculous, Cytotoxic |

| MK1688 (16) |

Verticillium hemipterigenum13 B, B4, G, C |

Antimalarial, antituberculous, Cytotoxic |

| J1 (17) |

Fusarium sp. F3114 B, B1, B2, B4 |

Against Botrytis cinerea |

| J2 (18) |

Fusarium sp. F3114 B, B1, B2, B4 |

Against Botrytis cinerea |

| J3 (19) |

Fusarium sp. F3114 B, B1, B2, B4 |

Against Botrytis cinerea |

| K1 (20) |

Fusarium sp. F3114 B, B1, B2, B4 |

Against Botrytis cinerea |

| L (21) | Unidentified fungus BCC262915 B, B4, H, I |

Antimalarial, antituberculous, cytotoxic |

| M1 (22) | Unidentified fungus BCC262915 B, B4, H, I |

Antimalarial, antituberculous, cytotoxic |

| M2 (23) | Unidentified fungus BCC262915 | Antimalarial, antituberculous, cytotoxic |

| N (24) | Unidentified fungus BCC262915 B, B4, H, I |

Antimalarial, antituberculous, cytotoxic |

| O1 (25) |

Verticillium hemipterigenum11 B, B4, G, C, H, I |

Antimalarial, antituberculous, cytotoxic |

| O2 (26) |

Verticillium hemipterigenum11 B, B4, G, C, H, I |

Antimalarial, antituberculous, cytotoxic |

| O3 (27) |

Verticillium hemipterigenum11 B, B4, G, C, H, I |

Antimalarial, antituberculous, cytotoxic |

| P1 (28) | Unidentified Fusarium sp. VI 0344116 | - |

| P2 (29) | Unidentified Fusarium sp. VI 0344116 | - |

Other enniatins that were isolated simultaneously are listed as well, where appropriate.

There are at least two other cyclohexadepsipeptides that resemble enniatins structurally, notably the destruxins17 and the beauvericins.18 What distinguishes these three is that the enniatins have alternating amino acid and hydroxy acid residues. Conversely, destruxins contain only one hydroxy acid and five amino acid residues, while beauvericins are comprised of alternating N-methylphenylalanine and hydroxy acid residues. Although all three types of cyclohexadepsipeptides have gained attention, likely due to their range of interesting biological activities,19,20 the chemistry and the wide-ranging biological activities of the enniatins have not been reviewed.

B. Biosynthesis of Enniatins

The biosynthesis of enniatins was reviewed in 2002.21 Briefly, enniatins are biosynthesized by a 347-kDa multifunctional enzyme, termed enniatin synthetase (ESyn).22,23 The initial biosynthetic step involves adenylation, which activates substrates as thioesters; this is followed by N-methylation and peptide bond formation. Once formed, the dipeptidol unit condenses with two other dipeptidols in an iterative fashion to form a linear hexadepsipeptide, which cyclizes in the final step to form the enniatin.24 ESyn has low substrate specificity for L-amino acids, thus permitting incorporation of different amino acids and contributing to the chemical diversity of the enniatins (Figure 1). Despite variability in the amino acid units, distinct Fusarium strains seem to incorporate preferentially some amino acids over others, as evidenced by the fact that certain enniatins can be isolated from only a particular species or strain of fungus. For example, Fusarium sambucinum preferably produces enniatin A (1) while Fusarium scirpi preferably makes enniatin B (2). 25 The D-hydroxy acid units are incorporated via D-2-hydroxyisovalerate dehydrogenase. This enzyme has high substrate specificity, as D-hydroxyisovaleric acid is conserved in most enniatins, except for enniatins H (14), I (15), L (21), M1 (22), M2 (23), and N (24) (Figure 1), and is present in most enniatin-producing fungi.26,27 To date, most enniatins have been biosynthesized naturally from producing fungi; however, enniatins C (9), G (13), and MK1688 (16) were produced via precursor-directed biosynthesis.13 It is conceivable that as more advanced knowledge is generated on the biosynthesis of these compounds, other enniatins could be biosynthesized by altering the insertion of either (or both) the amino acid or hydroxy acid substrates.

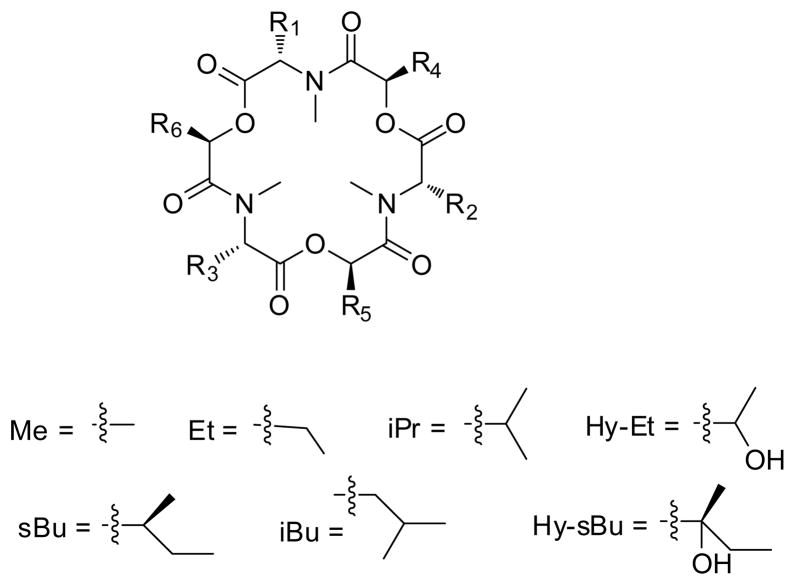

Figure 1. Enniatins and their amino acid and hydroxy acid compositions.

| enniatin | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (1) | sBu | sBu | sBu | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| A1 (3) | sBu | iPr | sBu | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| A2 (5) | sBu | iBu | sBu | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| B (2) | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| B1 (4) | iPr | sBu | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| a B2 (6) | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| a B3 (7) | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| B4 = D (8) | iPr | iPr | iBu | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| C (9) | iBu | iBu | iBu | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| * E1 (10) | iPr | iBu | sBu | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| * E2 (11) | iPr | sBu | iBu | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| F (12) | iBu | sBu | sBu | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| G (13) | iBu | iBu | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| H (14) | iPr | iPr | iPr | sBu | iPr | iPr |

| I (15) | iPr | iPr | iPr | sBu | sBu | iPr |

| MK1688 (16) | iPr | iPr | iPr | sBu | sBu | sBu |

| J1 (17) | iPr | iPr | Me | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| * J2 (18) | sBu | iPr | Me | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| * J3 (19) | Me | iPr | sBu | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| K1 (20) | iPr | iPr | Et | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| L (21) | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr | Hy-sBu |

| * M1 (22) | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr | sBu | Hy-sBu |

| * M2 (23) | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr | Hy-sBu | sBu |

| N (24) | iPr | iPr | iPr | sBu | sBu | Hy-sBu |

| * O1 (25) | iBu | iPr | iPr | sBu | iPr | iPr |

| * O2 (26) | iBu | iPr | iPr | iPr | sBu | iPr |

| * O3 (27) | iBu | iPr | iPr | iPr | iPr | sBu |

| *b P1 (28) | iPr | iPr | Hy-Et | iPr | iPr | iPr |

| *b P2 (29) | iBu | iPr | Hy-Et | iPr | iPr | iPr |

C. Chemistry: Inseparable Mixtures of Enniatins

Eighteen out of the 29 known enniatins have been isolated as single compounds. The other 11 have been isolated as five mixtures of homologs [enniatins E [re-examined below as enniatin E1 (10) and E2 (11)]; J2 (18), J3 (19); M1 (22), M2 (23); O1 (25), O2 (26), O3 (27); and P1 (28), and P2 (29)], despite the use of modern chromatographic techniques. Thus, their structures were characterized as mixtures.

Revisiting Enniatin E

In 1992, enniatins E1(10) and E2 (11) were the first reported inseparable mixture of enniatins (reported as enniatin E).10 Isolated with enniatins D (8) and F (12), the mixture of enniatins E1 (10) and E2 (11) was active as acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltranferase (ACT) inhibitor.28 These showed double the resonances in the NMR spectra when compared with enniatins D and F. The authors10 reported this as a mixture of two nonequivalent isomers after noting two key observations: (1) failing to see any inter-convertible spots on a silica gel TLC plate even at higher temperature, and (2) verifying by chemical degradation the amino acid and hydroxy acid components. While two homologs were proposed, a more efficient method is proposed below that serves to verify the identities based on mass spectrometry without the need for chemical degradation and illustrates, in general, some of the practical challenges of working with enniatin homologs. The difficulties in isolating and elucidating the individual components in the mixtures are oftentimes understated in the literature and, in our experience, daunting.

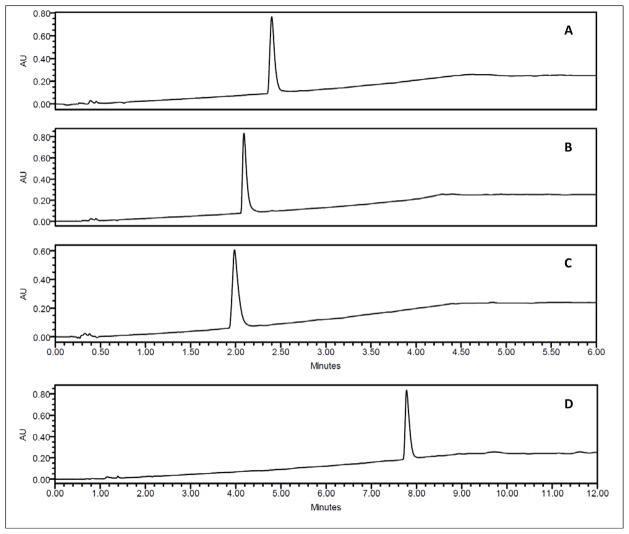

Recent studies on enniatins E1 (10) and E2 (11) emerged in our ongoing program to examine filamentous fungi for anticancer drug leads,29,30 when promising cytotoxicity was observed in an extract of culture MSX 44957 [Fusarium sp., sequence deposited in Genbank (JQ809513)]. This extract yielded dipeptidols 30 and 31 (discussed below) and enniatins B1 (4), D (8), and I (15). An additional compound, pseudo-enniatin E, was isolated as well that behaved like a dimer of enniatins, since it displayed twice the number of expected resonances in the 1H and 13C NMR spectra when compared to compounds 4, 8, and 15 and generated a quasi molecular ion of m/z = 1335, essentially twice the mass of most enniatins. Importantly, this compound displayed a single peak when examined with at least eight different HPLC/UPLC columns, including both normal- and reverse-phase chemistries and a chiral column and via testing a suite of solvent conditions (examples are illustrated in Figure 2). These observations led to a tentative initial structure with double the number of amino acids and hydroxy acids of the known enniatins, although there were some challenges using 2D NMR experiments to finalize the structure. However, upon re-running and re-analyzing the mass spectral data, a consistent molecular ion was observed at m/z = 668 for [M+H]+. These data were acquired independently in two different mass spectrometry laboratories, and we suspect that the initial observation of m/z = 1335 was an artifact, likely representing [2M+H]+. The molecular ion matched seven known enniatins in literature: A1 (3), E1 and E2 (10 and 11), G (13), I (15), and O1 (25), O2 (26), and O3 (27). Of these, the enniatin O homologs could be ruled out, as they were described as a mixture of three inseparable homologs,11 and our NMR data displayed patterns that were most similar to enniatins E1 (10) and E2 (11), although the original paper reported it as simply enniatin E.10

Figure 2.

Representative profile of enniatin E homologs when examined using an Acquity UPLC (Waters Corp., Milford, MA USA) and a solvent system of 20–100% MeOH-H2O using four different columns (all from Waters Corp.): A) HSS-C18 (1.8 μm; 50 × 2.1 mm); B) BEH-C18 (1.7 μm; 50 × 2.1 mm); C) BEH-Phenyl (1.7 μm; 50 × 2.1 mm); D) HSS-T3 (1.8 μm; 100 × 2.1 mm).

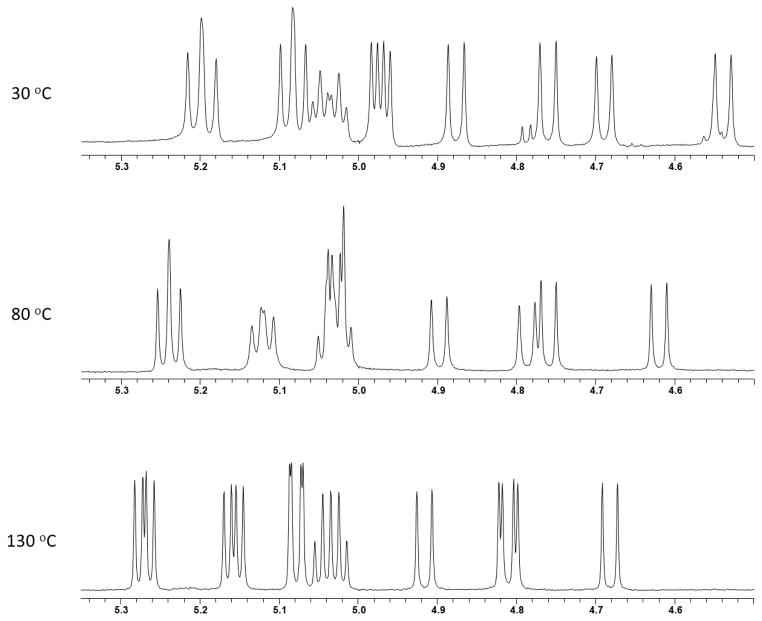

To further characterize this isolated compound and compare and contrast differences with the literature on enniatin E1 (10) and E2 (11),10 a full suite of 1- and 2D NMR data were acquired in different solvents, including CD3OD, DMSO-d6, CDCl3, and acetone-d6, to see whether better resolution could be achieved. NMR data (Table 2) acquired in acetone-d6 resulted in 1H NMR signals that were more spread out and better resolved. However, 1H NMR data in the literature10 were acquired in CDCl3 and compared favorably to the data on “pseudo-enniatin E” acquired also in CDCl3. 13C NMR data in acetone-d6 also yielded the best data set, followed by DMSO-d6, as most of the α-carbon resonances were individual peaks [12 peaks in acetone-d6, as opposed to just six resonances when analyzed in CDCl3 (Table 2)]. DMSO-d6, with a boiling point of 189 °C, was utilized for VT NMR experiments, which permitted NMR spectra acquisition at higher temperatures, as compared to other more volatile NMR solvents. The VT NMR experiments probed whether the compounds were a result of conformers (if signals coalesce at higher temperature)31 or homologous (if coalescence was not observed at any point as the temperature was elevated). In the case of the pseudo-enniatin E, coalescence was not observed. In fact, at some higher temperatures, the peaks appeared even sharper than at room temperature (Figure 3), further evidence that pseudo-enniatin E was a mixture of homologs and not conformers.

Table 2.

NMR Data for Enniatin E1 (10) and E2 (11) (500 MHz in Acetone-d6 and CDCl3)

| Position | Acetone-d6 | CDCl3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH, Mult. (J in Hz) | δC | δH, Mult. (J in Hz) | δC | |

| Hiv1 | ||||

| 1 | - | 170.3 | - | 170.5 |

| 2 | 5.15, d (9.0) | 75.0/74.9 | 4.95, d (9.0) | 77.2 |

| 3 | 2.18–2.22, m | 30.0 | 2.20–2.30, m | 30.4 |

| 4 | 0.92–0.98, m | 18.9 | 0.88–0.99, m | 19.1 |

| 5 | 0.92–0.98, m | 18.7 | 0.88–0.99, m | 19.0 |

| N-MeVal | ||||

| 6 | - | 169.0/168.6 | - | 170.2 |

| 7 | 4.88/4.51, d (10) | 60.8/62.5 | 4.91, d (9.5) | 61.3 |

| 8 | 2.18–2.22, m | 31.9 | 2.02, m | 33.6 |

| 9 | 0.92–0.98, m | 20.6 | 0.88–0.99, m | 20.2 |

| 10 | 0.92–0.98, m | 19.4 | 0.88–0.99, m | 19.6 |

| N-Me | 3.13, s | 30.9/32.3 | 3.14, s | 34.3 |

| Hiv2 | ||||

| 11 | - | 170.8/170.7 | - | 170.4 |

| 12 | 5.15, d (9.0) | 74.7/74.4 | 5.10, d (8.0) | 75.3 |

| 13 | 2.18–2.22, m | 29.8 | 2.20–2.30, m | 30.0 |

| 14 | 0.92–0.98, m | 18.0 | 0.88–0.99, m | 20.2 |

| 15 | 0.92–0.98, m | 18.0 | 0.88–0.99, m | 19.2 |

| N-MeIle | ||||

| 16 | - | 169.1/168.7 | - | 168.7 |

| 17 | 5.01/4.71, d (10) | 59.1/60.5 | 5.04, d (10) | 59.8 |

| 18 | 2.03, m | 33.9 | 2.20–2.30, m | 30.0 |

| 19 | 0.92–0.98, m | 17.7 | 0.88–0.99, m | 16.0 |

| 20 | 2.18–2.22, m | 24.9 | 2.20–2.30, m | 27.8 |

| 21 | 0.84–0.89, m | 9.8/10.2 | 0.83–0.87, m | 11.1 |

| N-Me | 3.10/3.11, s | 30.8/31.9 | 3.11, s | 33.8 |

| Hiv3 | ||||

| 22 | - | 169.3/169.4 | - | 170.9 |

| 23 | 5.29/5.25, d (8.0) | 74.5/74.4 | 5.20, d (9.0) | 75.5 |

| 24 | 2.18–2.22, m | 30.3 | 2.20–2.30, m | 30.0 |

| 25 | 0.92–0.98, m | 18.2 | 0.88–0.99, m | 19.6 |

| 26 | 0.92–0.98, m | 18.1 | 0.88–0.99, m | 18.9 |

| N-MeLeu | ||||

| 27 | - | 170.2/170.4 | - | 169.0 |

| 28 | 5.10, d (10) | 54.6/54.4 | 4.57, m | 57.3 |

| 29 | 1.85, m;1.64, m | 37.5 | 1.80, m; 1.74, m | 38.1 |

| 30 | 1.52, m | 24.8 | 1.53, m | 25.5 |

| 31 | 1.02, m | 19.7 | 1.01, d (7.0) | 20.5 |

| 32 | 1.45, m | 25.2 | 1.35, m | 25.0 |

| N-Me | 3.15/3.16, s | 31.4/31.5 | 3.07, s | 31.9 |

Values before and after slashes are chemical shifts for the individual homologs

Figure 3.

1H NMR profile of enniatin E homologs (α-proton region) at three temperatures in DMSO-d6 (500 MHz).

To determine the configuration of pseudo-enniatin E, acid hydrolysis was performed using methods described previously.32 The sample was extracted thrice with CH2Cl2, and both the aqueous and organic extracts were subjected to chiral HPLC analyses by comparing them to standards, which demonstrated that pseudo-enniatin E had the same composition of amino acids and hydroxy acids, all with the same configurations, as enniatins E1 (10) and E2 (11) (Hiv, N-MeIle and N-MeLeu).

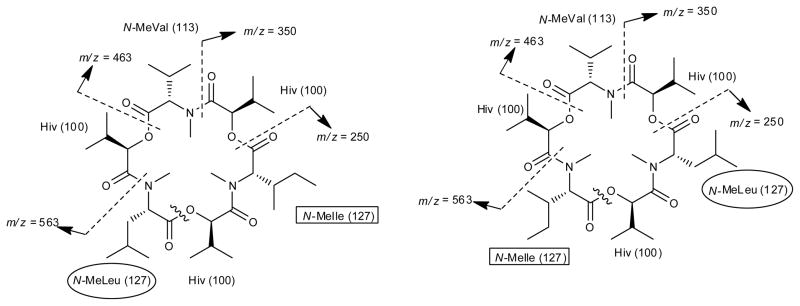

Analysis of the mass fragmentation (Figure 4) through MSn experiments for pseudo-enniatin E (m/z = 690 [M+Na]+) showed fragments consistent with the sequential loss of N-MeIle or N-MeLeu [the two amino acids being isomeric (m/z = 563)], Hiv (m/z = 463), N-MeVal (m/z = 350), and another Hiv (m/z = 250). Since enniatins have alternating amino acid and hydroxy acid residues, the initial sequential loss of residues revealed that N-MeVal was flanked by two Hiv units. The Hiv units had to be flanked by the two other amino acid residues - N-MeIle and N-MeLeu - which in turn were separated by one last Hiv unit. A second pattern emerged from the same mass spectrum that displayed sequential loss of N-MeVal (m/z = 577), followed by Hiv + NMeLeu (or NMeIle) (m/z = 350). Hence, in order for enniatin E to display double the resonances in the NMR spectra, the two homologs, which we now suggest should be termed enniatin E1 (10) and E2 (11) (Figure 1), had the following cyclic order: (1) N-MeIle-Hiv-N-MeVal-Hiv-N-MeLeu-Hiv (E1) and (2) N-MeLeu-Hiv-N-MeVal-Hiv-N-MeIle-Hiv (E2) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

MSn mass fragmentation of homologs of enniatin E. The boxes and circles highlight where N-MeIle and N-MeLeu were reversed in the two homologs.

Isolation of 1,4-perhydrooxazine-2,5-dione compounds 30 and 31

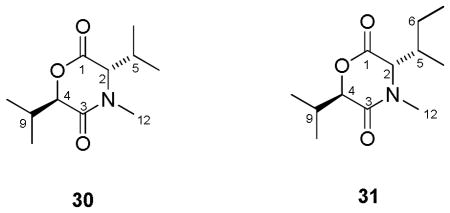

Two other compounds (30 and 31) were isolated together with the enniatins from the same Fusarium species (MSX 44957). These dipeptidols, characterized based on HRESIMS and NMR data (Table 3), may represent building blocks of enniatins in cyclized form.33 Compound 30 showed m/z = 214.1452 [M+H]+, corresponding to a molecular ion of C11H19NO3 (calculated for C11H20NO3; 214.1443), while compound 31 showed m/z = 228.1599 [M+H]+, corresponding to a molecular ion of C12H21NO3 (calculated for C12H22NO3; 228.1608). To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the isolation of these as natural products, although compound 30 was obtained as a by-product upon hydrolysis and lactonization of N-α-bromoisovaleryl-N-MeVal in a synthesis paper.33

Table 3.

NMR data for compounds 30 and 31 (500 MHz in CDCl3)

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | 30 | 31 | ||

|

| ||||

| δH, Mult. (J in Hz) | δC | δH, Mult. (J in Hz) | δC | |

|

| ||||

| 1 | - | 170.4 | - | 170.3 |

| 2 | 4.47, d (9.0) | 63.5 | 4.66, d (9.0) | 61.8 |

| 3 | - | 169.4 | - | 169.2 |

| 4 | 5.11, d (8.0) | 75.9 | 5.15, d (9.0) | 75.6 |

| 5 | 2.27, m | 28.1 | 2.08, m | 34.0 |

| 6 | 0.86, d (7.0) | 19.5 | 1.45, m; 1.11, m | 25.3 |

| 7 | 1.03, d (7.0) | 18.9 | 1.00, d (7.0) | 16.3 |

| 8 | - | - | 0.89, t (8.0) | 11.0 |

| 9 | 2.27, m | 30.1 | 2.30, m | 29.9 |

| 10 | 0.96, d (7.0) | 20.7 | 1.02, d (7.0) | 18.7 |

| 11 | 0.93, d (7.0) | 18.7 | 0.97, d (7.0) | 18.5 |

| 12 | 3.10, s | 33.5 | 3.13, s | 33.1 |

There are likely several plausible explanations for the existence of these dipeptidols in cultures of MSX 44957. Compounds 30 and 31 could be synthesized by a mutated enzyme, where instead of proceeding to an elongation step, the enzyme terminates the process and cyclizes at the dipeptidol stage. One could envisage them as the result of limited substrates, although we never limited nutrients intentionally. Alternatively, they may have formed spontaneously due to thermodynamically stable six-membered rings or could be a by-product of metabolism. Regardless, their identification concomitant with a series of enniatins may be valuable for future biosynthetic considerations.

Structure Elucidation: Techniques and Challenges

The structures of the enniatins have been determined by a variety of physical and chemical methods. With respect to X-ray crystallography, only enniatins B (2)34 and N (24)15 have been reported in the literature. Alternatively, the use of NMR spectroscopy is more prominent. The 18-membered cyclic backbone of all enniatins consists of carbonyl carbons (three amides and three esters) and six α-carbons, three of which are oxygenated (δC 73 ~ 77 ppm) and three of which are connected to nitrogen atoms (δC 56 ~ 65 ppm). An α-proton (δH 4.44 ~ 5.32 ppm) is connected to each α-carbon in the backbone, while a methyl group is connected to each nitrogen in the amino acid portion (δH 3.08 ~ 3.18 ppm), except for enniatins B2 and B3, which have one and two less N-methyl moieties, respectively.9 The connectivities of each amino and hydroxy acid residue are established by HMBC data, which typically show correlations from the α-protons to two carbonyl carbons, and from the N-methyl protons to the ester carbonyl carbon that acylates that particular amino acid. The identity of each residue can be determined by COSY and TOCSY data and by multiplicities and J-values. Although signals for the methyl groups of Val, Leu, and Ile are typically overlapped in an enniatin 1H NMR spectrum, a careful integration of the area will facilitate counting the number of methyl groups in the structure, and these are reported typically as interchangeable values. The chemical shifts of the β-protons for amino acids depend on whether the structure has a Val (δH 2.20 ~ 2.30 ppm), Leu (δH 1.70 ~ 1.80 ppm), or Ile (δH 2.09 ~ 2.11). The multiplicity of an α-proton of an Ile (triplet) would also appear different from that of a Leu (doublet) or Val (doublet). Moreover, the β-carbon of Ile differs in chemical shift from Leu (δC 33 ~ 35 ppm versus 37 ~ 38 ppm, respectively). Also, the DEPT-135 experiment can differentiate between Ile and Leu based upon the chemical shift of the carbon that changed phase. Biosynthetic considerations can also assist in the structure elucidation process. Although the enniatin synthases were mentioned to have low substrate specificity for L-amino acids, a study also showed that this enzyme preferentially incorporates only certain sizes of amino acid side chains.24 Thus, alanine and α-aminobutyric acid are the only other amino acids shown to be incorporated into a naturally produced enniatin, specifically enniatins J1 (17), J2 (18), J3 (19) and K1 (20).14 In summary, if the enniatin will not form crystals suitable for X-ray analysis, NMR spectroscopy may be the best solution, although the spectrum will appear crowded and overlapped in certain diagnostic regions. Focusing on how resonances can be ascribed to distinct amino acid or hydroxy acid residues, particularly Val, Leu, Ile, and Hiv, should narrow the work involved considerably.

The modern challenge in the structure elucidation of enniatins arises when homologs are isolated. These enniatins co-elute and appear as a single peak in chromatographic separations (e.g. Figure 2), even using modern stationary phases, a suite of mobile phases, and even a chiral column. As inseparable mixtures, they display double (as exhibited by enniatins E1/E2, J2/J3 and M1/M2) or triple (as shown by enniatins O1/O2/O3) the resonances in the NMR spectra.10,11,14,15 In these situations, neither a change in solvent nor the use of variable temperature experiments results in simplification of resonances or coalescence of signals, thus ruling out the possibility of conformational isomers, as shown with compounds like bassianolide.31 Also, mass spectral data suggests a molecular weight in the range of typical enniatins (i.e. 611 to 683 a.m.u.). For certain enniatins, the structures of such homologs were elucidated in different ways, and a few cogent examples are discussed below.

Enniatin J2/J314

In conjunction with NMR data, mass spectrometry played a key role in the structure elucidation of enniatins J2 (18) and J3 (19), particularly the use of ESIMSn to determine the sequence of residues. Isolated together with enniatins J1 (17) and K1 (20) from an unidentified Fusarium strain, these homologs displayed a m/z of 626.3972 [M+H]+. NMR data and fragmentation information via ESIMS2–4 indicated the presence of N-MeAla (m/z = 85), N-MeVal (m/z = 113), N-MeIle (m/z = 127), and Hiv (m/z = 100). The sequence was determined by subjecting the homologs to partial acid hydrolysis to obtain linear depsipeptides, which generated two major fractions that were subjected to further ESIMSn. One fraction displayed the sequential loss of N-MeIle followed by N-MeAla, after the initial loss of Hiv. Keeping in mind that enniatins have alternating amino acid-hydroxy acid residues, these results indicated that N-MeIle and N-MeAla had to be on opposite ends of the linear depsipeptide and that N-MeVal separated both amino acids. In support of this finding, the other fraction showed a loss of N-MeVal followed by N-MeAla, after the initial loss of Hiv. Using the same logic, the N-MeIle had to be between N-MeVal and N-MeAla. Coupling these finding together distinguished the sequences of the two homologs (Figure 1).

Enniatin M1/M215

Isolated from an unidentified fungus and reported as one of the first enniatins with a hydroxyl group in the side chain of the Hiv portion of the structure [the others being enniatins L (21) and N (24)], enniatins M1 (22) and M2 (23) were isolated as a single peak by reversed phase HPLC. However, this isolate displayed twice the expected resonances in both the 1H- and 13C NMR spectra for a single enniatin molecule. Extensive 1- and 2D NMR analyses revealed that these homologs contained six units of N-MeVal, two units of Hiv, two units of 2,3-dihydroxy-3-methylpentanoic acid (Dmp), and two units of 2-hydroxy-3-methylpentanoic acid (Hmp). Even though there was no direct evidence for the exact sequence of residues for homologs M1 (22) and M2 (23), the authors suggested that there had to be a difference in their connectivities in order for these two homologs to display different NMR resonances. Indirectly, the NMR data from the related compound, enniatin N (24),15 from which a crystal structure was obtained, showing the presence of Hmp and Dmp residues in the hydroxy acid portion of the molecule, was used to match the resonances observed in enniatins M1 (22) and M2 (23) (Figure 1).

Enniatin O1/O2/O311

Showing not just two but three sets of NMR resonances, enniatins O1 (25), O2 (26) and O3 (27) were obtained from Verticillium hemipterigenum, whose fermentation conditions were optimized for enniatin production. NMR data (both 1H and 13C spectra) revealed that these homologs consisted of six N-MeVal, three N-MeLeu, six Hiv, and three Hmp residues. Further structural analyses by NMR and mass spectrometry were performed on four amide fragments, produced from partial degradation using LiBH4 followed by acetylation. The 1H and 13C NMR data of the fragments matched similar data obtained from known enniatins [B (2), B4 (8), and H (14)] subjected to the same reaction. In short, the absolute configuration and the sequences of the amino and hydroxy acid residues were derived by comparison with known compounds and by mass spectral analyses of the fragments, thus establishing the structures for enniatins O1 (25), O2 (26), and O3 (27).

Identification of the configuration of the amino acid and hydroxy acid residues

The amino acid residues in all of the 29 enniatins described to date have the L-configuration, likely because the biosynthetic enzyme, ESyn, has a preference over the D-isomer. In a similar fashion, all of the hydroxy acids have the D-configuration, possibly due to the preference of the D-2-hydroxyisovalerate dehydrogenase. Although some of the enniatin literature is scant on experimental results, it may be a fair assumption, at least initially, that the L-amino acids and D-hydroxy acids are incorporated based largely on biosynthetic considerations. However, a simple acid hydrolysis can be performed on just a milligram quantity of the material and compared with standards using a chiral column [see discussion of enniatin E1 (10) and E2 (11)]. In this way, no derivatizations are required that would diminish the yield of the “product”. Moreover, in cases where inseparable homologs are present, acid hydrolysis can help determine the identity of the residues [see discussion of enniatin E1 (10) and E2 (11)]. Also, partial degradation using LiBH4 followed by acetylation with acetic anhydride yielded fragments that were analyzed by NMR and mass spectrometry, as exemplified by enniatins O1 (25), O2 (26), and O3 (27).10 In summary, although the biosynthetic considerations for the configuration of the residues have been consistent for 29 enniatins, to date, taking the research a step further and determining the configurations experimentally is straight forward and should be pursued; compounds with an unanticipated configuration could be uncovered in the future.

D. Biological Activities

Antimicrobial Activities

Enniatins have been shown to exhibit a wide array of biological activities, and one of the earliest reported was antimicrobial activity towards Mycobacterium spp., Staphylococcus spp., Bacillus spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli.1,35,36 Enniatins B (4), B4 (8), H (14), I (15), G (13), C (9), MK1688 (16), O1 (25), O2 (26) and O3 (27) were shown to inhibit the activity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.11,13 Furthermore, a recent study focused on the ability of enniatins to inhibit mycotoxigenic molds, such as Fusarium verticillioides, F. sporotrichioides, F. oxysporum, F. poae, F. tricinctum, F. proliferatum, Beauveria bassiana, Trichoderma harzianum, Aspergillus flavus, A. parasiticus, A. fumigatus, A. ochraceus, and Penicillium expansum.37 Interestingly, of the four enniatins used in that study [A (1), A1 (3), B (4), B1 (4)], only enniatin B (2) displayed inhibition of some of the molds. Enniatins were also tested against Botrytis cinerea, a fungal phytopathogen that causes gray mold to many host species and infects seedlings stored in humid conditions. Of the series of enniatins tested, enniatins B (2), B4 (8), and K1 (20) were found to partially inhibit spore germination of B. cinerea.14

One mixture of enniatins, obtained from Fusarium lateritium WR, strain 437,38 has been developed as an antimicrobial, fusafungine, and is administered as a topical treatment of upper respiratory tract infections by oral and/or nasal inhalation.38 The drug is sold under the trade names Locabiotal (United Arab Emirates and Taiwan), Bioparox (Poland and Slovakia), Locabiosol (USA and Canada), and Fusaloyos (Spain) and is manufactured by Laboratoires Servier, a Frenchpharmaceutical company. Fusafungine showed bacteriostatic activity against a suite of microorganisms, such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Streptococcus pneumoniae, S. pyogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus.

Enzyme Inhibitors

Enniatins A (1), A1 (3), B (2), B1 (4), D (8), E1/E2 (10 and 11) and F (12) have been probed, at least in a limited fashion, as enzyme inhibitors, particularly acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT), although their activities were moderate compared to beauvericin, one of the most potent ACAT inhibitors of microbial origin.28 Nevertheless, such inhibitions could be significant in the treatment and prevention of atherosclerosis and hypercholesterolemia. In a separate study, the hypolipidaemic action of enniatin B (2) could be ascribed both to ACAT inhibition and a reduction of triglyceride synthesis, thus diminishing the pool of the free fatty acid in cells.39 Also, enniatin B (2) was found to inhibit 3′,5′-cyclo-nucleotide phosphodiesterase and was able to bind calmodulin.40,41 This mode of action suggested an altering of signal transduction mechanisms of enzymes that are dependent on calmodulin, such as cyclic nucleotidase and protein kinases. In summary, although the number of studies of enniatins vs enzymes is somewhat limited, they seem to possess activities that warrant further exploration.

Cytotoxicity and Anticancer Properties

Towards cancer research, a study found enniatins B (2), B1 (4), and D (8) to inhibit pleiotropic drug resistance 5 protein (Pdr5p), an ATP-binding cassette that is one of the major causes of drug resistance against a variety of compounds, including drugs like tamoxifen and doxorubicin.42 While many inhibitors of multidrug resistance (MDR) proteins have been described, these enniatins are important because they are found to be potent and specific for Pdr5p but are less toxic than other such leads.42 In another cancer-related study, enniatins A1 (3) and B1 (4) were found to induce apoptotic cell death and disrupt extracellular regulated protein kinase (ERK), a mitogen-activated protein kinase associated with cell proliferation,43 while a mixture of enniatins A (1), A1 (3), B (2), and B1 (4) also induced apoptosis in several human cancer cell lines at low molar concentrations after 24 hours of treatment.44

Our studies on enniatins were initiated based on cytotoxicity of an extract of the fungus Fusarium sp. (MSX 44957) tested against a panel of three human cell lines in culture (the methods and strategy for such studies have been outlined previously32,45). As described earlier in this manuscript, a series of compounds were isolated and characterized, including enniatins E1 (10), E2 (11), B1 (4), D (8), I (15), and compounds 30 and 31. Of these, the enniatins were more potent than the related building blocks, i.e. compounds 30 and 31, with the homolog mixture of enniatins E1 (10) and E2 (11) being the most potent (see Table 4). Despite these encouraging results, the activity of the enniatins was still approximately one to two orders of magnitude less potent than the positive control, camptothecin.

Table 4.

Cytotoxicity of enniatins and other compounds isolated from Fusarium sp. (MSX 44957) against a panel of human tumor cell lines.

| Compound | IC50 values (in μM)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 | H460 | SF268 | |

| Enniatin B1 (4) | 1.4 | 1.2 | 2.2 |

| Enniatin E1/E2 (10/11) | 0.5 | 0.7 | 2.6 |

| Enniatin D (8) | 2.7 | 2.8 | 4.0 |

| Enniatin I (15) | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| 30 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 10 |

| 31 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 4.3 |

| Camptothecinb | 0.07 | 0.008 | 0.50 |

IC50 values were determined as the concentration required to reduce cellular proliferation by 50% relative to untreated controls following 72 h or continuous exposure using methods described in detail previously.51,52

Positive control.

Other Biological Activities

Not surprising for a series of compounds first described in the 1940s, the enniatins have shown a variety of other biological activities; a recent review highlights several others not covered in this manuscript.46 In particular, enniatin A (1) was shown to possess anthelmintic properties against Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, Trichinella spiralis, and Heterakis spumosa.47 Moreover, analogs of enniatin A (1) were synthesized, and two new derivatives were shown to possess strong in vivo activity against H. contortus in sheep.48 A mixture of enniatins A (1), A1 (3), B (2), B1 (4) was cytotoxic against the Spodoptera frugiperda cell line, which is an insect cell line used to probe for in vivo cytotoxicity of fungal metabolites.49 Several of the enniatins [B (2), B4 (8), H (14), I (15), G (13), C (9), MK1688 (16), O1 (25), O2 (26) and O3 (27)] were found to inhibit proliferation of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.11,13 Given this diverse range of activities, future researchers should be encouraged to examine the enniatins against a broad range of biological targets.

Enniatins as Ionophores

Given the pore shape of the cyclodepsipeptide core of enniatins, their ionophoric behavior has been suggested since the 1960s.50 More recently, a study on the electrophysiological properties of an enniatin mixture containing A (1), A1 (3), B (2), B1 (4) revealed that they incorporate easily into the cell membrane as a passive channel and form cation selective pores.40 By forming complexes with cations like K+, Na+, and Ca2+, enniatins evoke changes in intracellular ion concentration, disrupting cell function. Indeed, this may explain the broad range of biological activities observed for the enniatins.

E. Conclusion

Enniatins are secondary metabolites that have an interesting cyclohexadepsipeptide structure and that are produced, primarily, by Fusarium species of fungi. Although 29 of these have been described in the literature, it is anticipated that other analogs exist in nature, particularly given the diverse biosynthetic possibilities in the side chains of these compounds. Moreover, mixtures of homologs, where the position of amino acid units have been shuffled, will continue to challenge the skills and resolve of natural products chemists. Studies on these compounds have been, and likely will be in the future, driven by their broad range of biological activities. To date, one pharmaceutical product, fusafungine, has been derived from the enniatins; the future awaits other applications.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by P01 CA125066 from the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA. We thank Ms. Audrey Adcock and Dr. David J. Kroll, North Carolina Central University, for the cytotoxicity measurements. We also thank the David H. Murdock Research Institute (Kannapolis, NC), the High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Facility at the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA), and the Proteomics and Metabolomics Facility at Colorado State University (Fort Collins, CO) for some of the mass spectrometry data.

References

- 1.Gaumann E, Roth S, Ettlinger L, Plattner PA, Nager U. Ionophore antibiotics produced by the fungus Fusarium orthoceras var. enniatum and other. Fusaria Experientia. 1947;3:202–203. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plattner PA, Nager U, Boller A. Wilting agents and antibiotics. VII Isolation of new type antibiotics from. Fusaria Helv Chim Acta. 1948;31:594–602. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19480310240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook AH, Cox SF, Farmer TH. Antibiotics produced by fungi, and a new phenomenon in optical resolution. Nature. 1948;162:61. doi: 10.1038/162061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Audhya TK, Russell DW. Natural enniatin A, a mixture of optical isomers containing both erythro- and threo-N-methyl-L-isoleucine residues. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1974;7:743–746. doi: 10.1039/p19740000743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Audhya TK, Russel DW. Production of enniatin A. Can J Microbiol. 1973;19:1051–1054. doi: 10.1139/m73-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deol BS, Ridley DD, Singh P. Isolation of cyclodepsipeptides from plant pathogenic fungi. Aust J Chem. 1978;31:1397–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strongman DB, Strunz GM, Giguere P, Yu CM, Calhoun L. Enniatins from Fusarium avenaceum isolated from balsam fir foliage and their toxicity to spruce budworm larvae, Choristoneura fumiferana (Clem) (Lepidoptera, Tortricidae) J Chem Ecol. 1988;14:753–764. doi: 10.1007/BF01018770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blais LA, Apsimon JW, Blackwell BA, Greenhalgh R, Miller JD. Isolation and characterization of enniatins from Fusarium avenaceum Daom-196490. Can J Chem. 1992;70:1281–1287. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visconti A, Blais LA, Apsimon JW, Greenhalgh R, Miller JD. Production of enniatins by Fusarium acuminatum and Fusarium compactum in liquid culture: isolation and characterization of three new enniatins, B2, B3, and B4. J Agric Food Chem. 1992;40:1076–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomoda H, et al. New cyclodepsipeptides, enniatins D, E and F produced by Fusarium sp FO-1305. J Antibiot. 1992;45:1207–1215. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Supothina S, Isaka M, Kirtikara K, Tanticharoen M, Thebtaranonth Y. Enniatin production by the entomopathogenic fungus Verticillium hemipterigenum BCC 1449. J Antibiot. 2004;57:732–738. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin YC, et al. A novel compound enniatin G from the mangrove fungus Halosarpheia sp (strain 732) from the South China Sea. Aust J Chem. 2002;55:225–227. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilanonta C, et al. Unusual enniatins produced by the insect pathogenic fungus Verticillium hemipterigenum: isolation and studies on precursor-directed biosynthesis. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:1015–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pohanka A, et al. Enniatins of Fusarium sp strain F31 and their inhibition of Botrytis cinerea spore germination. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:851–857. doi: 10.1021/np0340448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vongvilai P, et al. Isolation and structure elucidation of enniatins L, M1, M2, and N: novel hydroxy analogs. Helv Chim Acta. 2004;87:2066–2073. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uhlig S, Ivanova L, Petersen D, Kristensen R. Structural studies on minor enniatins from Fusarium sp VI 03441: novel N-methyl-threonine containing enniatins. Toxicon. 2009;53:734–742. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedras MS, Irina Zaharia L, Ward DE. The destruxins: synthesis, biosynthesis, biotransformation, and biological activity. Phytochemistry. 2002;59:579–596. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamill RL, Higgens CE, Boaz HE, Gorman M. Structure of beauvericin, a new depsipeptide antibiotic toxic to Artemia salina. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969:4255–4258. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scherkenbeck J, Jeschke P, Harder A. PF1022A and related cyclodepsipeptides - a novel class of anthelmintics. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:759–777. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anke H. Insecticidal and Nematicidal Metabolites from Fungi. In: Hofrichter M, editor. The Mycota. 2. X. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg, Germany: 2010. pp. 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hornbogen T, Glinski M, Zocher R. Biosynthesis of depsipeptide mycotoxins in Fusarium. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2002;108:713–718. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herrmann M, Zocher R, Haese A. Enniatin production by Fusarium strains and its effect on potato tuber tissue. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:393–398. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.393-398.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zocher R, Keller U, Kleinkauf H. Enniatin synthetase, a novel type of multifunctional enzyme catalyzing depsipeptide synthesis in Fusarium oxysporum. Biochemistry. 1982;21:43–48. doi: 10.1021/bi00530a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krause M, et al. Directed biosynthesis of new enniatins. J Antibiot. 2001;54:797–804. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.54.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pieper R, Kleinkauf H, Zocher R. Enniatin synthetases from different Fusaria exhibiting distinct amino acid specificities. J Antibiot. 1992;45:1273–1277. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feifel SC, et al. In vitro synthesis of new enniatins: probing the alpha-D-hydroxy carboxylic acid binding pocket of the multienzyme enniatin synthetase. Chembiochem. 2007;8:1767–1770. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee C, Gorisch H, Kleinkauf H, Zocher R. A highly specific D-hydroxyisovalerate dehydrogenase from the enniatin producer Fusarium sambucinum. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11741–11744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomoda H, et al. Inhibition of acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase activity by cyclodepsipeptide antibiotics. J Antibiot. 1992;45:1626–1632. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orjala J, Oberlies NH, Pearce CJ, Swanson SM, Kinghorn AD. Discovery of potential anticancer agents from aquatic cyanobacteria, filamentous fungi, and tropical plants. In: Triginali C, editor. Bioactive Compounds from Natural Sources. Natural Products as Lead Compounds in Drug Discovery. 2. Taylor & Francis; London, UK: 2012. pp. 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kinghorn AD, et al. Discovery of anticancer agents of diverse natural origin. Pure Appl Chem. 2009;81:1051–1063. doi: 10.1351/PAC-CON-08-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanaoka M, et al. Bassianolide, a new insecticidal cyclodepsipeptide from Beauveria bassiana and Verticillium lecanii. Agric Biol Chem. 1978;42:629–635. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sy-Cordero AA, et al. Cyclodepsipeptides, sesquiterpenoids, and other cytotoxic metabolites from the filamentous fungus Trichothecium sp (MSX 51320) J Nat Prod. 2011;74:2137–2142. doi: 10.1021/np2004243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook AHC, SF 2:5-Diketomorpholines, their synthesis and stability. J Chem Soc. 1949:2347–2351. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kratky C, Dobler M. The crystal structure of enniatin B. Helv Chim Acta. 1985;68:1798–1803. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jestoi M. Emerging Fusarium-mycotoxins fusaproliferin, beauvericin, enniatins, and moniliformin - a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2008;48:21–49. doi: 10.1080/10408390601062021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vesonder RF, Golinski P. Metabolites of Fusarium. In: Chelkowski J, editor. Fusarium: Mycotoxins, Taxonomy and Pathogenicity. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1989. pp. 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meca G, et al. Antifungal effects of the bioactive compounds enniatins A, A1, B, B1. Toxicon. 2010;56:480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.German-Fattal M. Fusafungine, an antimicrobial with anti-inflammatory properties in respiratory tract infections - review, and recent advances in cellular and molecular activity. Clin Drug Investig. 2001;21:653–670. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trenin AS, et al. The hypolipidemic action of antibiotic 86/88 (enniatin B) in a hepatoblastoma G2 cell culture. Antibiot Khimioter. 2000;45:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamyar M, Rawnduzi P, Studenik CR, Kouri K, Lemmens-Gruber R. Investigation of the electrophysiological properties of enniatins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;429:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mereish KA, Solow R, Bunner DL, Fajer AB. Interaction of cyclic peptides and depsipeptides with calmodulin. Pept Res. 1990;3:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hiraga K, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, Hamanaka N, Oda K. Enniatin has a new function as an inhibitor of Pdr5p, one of the ABC transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:1119–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watjen W, et al. Enniatins A1, B and B1 from an endophytic strain of Fusarium tricinctum induce apoptotic cell death in H4IIE hepatoma cells accompanied by inhibition of ERK phosphorylation. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009;53:431–440. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dornetshuber R, et al. Enniatin exerts p53-dependent cytostatic and p53-independent cytotoxic activities against human cancer cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:465–473. doi: 10.1021/tx600259t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayers S, et al. Cytotoxic xanthone-anthraquinone heterodimers from an unidentified fungus of the order Hypocreales (MSX 17022) J Antibiot. 2012;65:3–8. doi: 10.1038/ja.2011.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Firakova S, Proksa B, Sturdikova M. Biosynthesis and biological activity of enniatins. Pharmazie. 2007;62:563–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pleiss U, et al. Synthesis of a radiolabeled enniatin cyclodepsipeptide [H-3-methyl]JES 1798. Journal of Labelled Compounds & Radiopharmaceuticals. 1996;38:651–659. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeschke P, et al. Synthesis and anthelmintic activity of cyclohexadepsipeptides with (S,S,S,R,S,R)-configuration. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:3285–3288. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00688-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fornelli F, Minervini F, Logrieco A. Cytotoxicity of fungal metabolites to lepidopteran (Spodoptera frugiperda) cell line (SF-9) J Invertebr Pathol. 2004;85:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shemyakin MM, et al. Cyclodepsipeptides as chemical tools for studying ionic transport through membranes. J Membr Biol. 1969;1:402–430. doi: 10.1007/BF01869790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]