Abstract

1.Labelling plants with 15N and 13C stable isotopes usually require cultivation of plants in isotopically enriched soil and gas-tight labelling chambers - both approaches are not suitable if one aims to investigate in situ species interactions in real plant communities.

2.In this greenhouse experiment, we tested a labelling method in which dual-labelled (15N, 13C) urea solution is brushed directly onto leaves of twelve temperate grassland species representing grasses, non-leguminous forbs and legumes.

3.Across all plant species, shoots (15N: 0·145; 13C: 0·090 atom percent excess, APE) and roots (15N: 0·051; 13C: 0·023 APE) were significantly enriched after five daily labelling events. Generally, isotopic enrichments were significantly higher in shoots than in roots. No clear pattern of absolute isotopic enrichment was observed between plant functional groups; however, grasses showed a more even allocation between shoots and roots than forbs and legumes. Isotopic enrichment levels after 4 weeks were lower, higher or unchanged compared to those of week one and varied between species or plant parts.

4.Considering the consistent enrichment levels and simplicity of this method, we conclude that it can be applied widely in ecological studies of above-belowground plant–plant or plant–animal interactions even in real plant communities.

Keywords: carbon, foliar labelling technique, IRMS, native grassland species, nitrogen, stable isotope tracers, urea

Introduction

Stable isotope labelling is a powerful, quantitative technique used in current ecological research to validate and complement studies at natural abundance levels, for example to elucidate nutrient cycles and organismic interactions within ecosystems (Michener & Kaufman 2007). When studying food webs that involve plants, a common approach is to introduce isotopically enriched plant material into the system and trace elements derived from them in the other food web components (e.g. Simard et al. 1997; Herman et al. 2000; Martens et al. 2001; Hood-Nowotny & Knols 2007; Seeber et al. 2009). However, to produce isotopically labelled plant material, plants are usually cultivated in sophisticated labelling chambers for continued release of 13CO2 that are often not available in ecological laboratories (Berg et al. 1991). Pulse-labelling, in which plants are exposed periodically to labelled CO2, circumvents many of the logistical constraints and even allows labelling outside of the laboratory, although airtight labelling chambers are still needed (Bromand et al. 2001; Leake et al. 2006; Subke et al. 2009).

Recently, Hertenberger & Wanek (2004) compared 15N labelling efficiencies of several alternative methods (e.g. root feeding, stem infiltration, leaf tip feeding, vacuum infiltration, surface abrasion) on three plant species (forbs: Brassica napus L., Centaurea jacea L.; grass: Lolium perenne L.). Generally, their results showed marked differences in plant labelling effectiveness, both with respect to the method applied and the plant species used. Leaf vacuum infiltration and leaf surface abrasion resulted in the lowest 15N enrichments of roots and shoots (<1% APE, atom percent excess), while root feeding and stem infiltration (8% APE in shoots and 15% in roots) achieved the best results. Overall, stem infiltration effectively 15N labelled plants with thicker stems, while feeding via cut leaf tip was most effective for graminoid plants.

Another frequently used alternative, namely spraying isotopically labelled urea onto the plant surface, has been applied to various crop plants (Schmidt & Scrimgeour 2001; Rasmussen et al. 2007; Wichern et al. 2007; El-Naggar et al. 2008). However, while spraying generally seems to work well, it has the disadvantage that the soil surface needs to be protected to avoid contamination with stable isotopes, thus preventing its use in stands with a dense plant cover where only specific plants need to be labelled. Moreover, it is not known how effective foliar labelling is for various wild plant species and to what extent the isotopic tracer is allocated within the plant.

The objectives of the current study were to test whether (1) dual isotopic labelling with 15N and 13C applied directly onto the leaf surface is a suitable method for labelling a variety of grassland plant species, (2) isotopic enrichments differ between plant functional groups and between shoots and roots and (3) the persistence of the isotopic label differs between plant species. We conducted a pot experiment in the greenhouse in which 12 plant species comprising three different functional groups (grasses, forbs, legumes) were grown in field soil. We hypothesised that labelling efficacy differs among species according to inherent morphological traits and differences in biomass allocation.

Material and methods

Plant and soil material

The experiment was conducted in an unheated greenhouse at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, from March to June 2008. Foliar isotopic labelling was tested on 12 different plant species that commonly occur in Central European low-fertile grasslands. Test plants included the graminoids –Arrhenatherum elatius L., Briza media L., Bromus erectus Huds., Dactylis glomerata L.; the non-legume forbs –Leucanthemum ircutianum DC., Plantago lanceolata L., Rumex obtusifolius L., Salvia pratensis L., Knautia arvensis Coult.; and the herbaceous legumes –Lotus corniculatus L., Medicago lupulina L., Trifolium pratense L. Seeds were obtained from a commercial supplier (Rieger Hofmann GmbH, Blaufelden-Raboldshausen, Germany). We grew one specimen of each plant species individually per pot (3 L volume, 14·5 × 14·5 cm side length, 22 cm height); to ensure regular germination, we initially placed three seeds on the soil surface but later reduced the number of seedlings to one plant per pot. Pots were filled with a 2 : 1 mixture of field soil and quartz sand (quartz sand particle size 1·4–2·2 mm); the mixture had a pH 7·6, N = 0·092 g kg−1, P = 64·5 mg kg−1, K = 113·6 mg kg−1. The field soil was obtained from an arable field of the Experimental Farm of the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Groß-Enzersdorf, sieved through a 1-cm sieve and sterilized at 120°C for 12 hours before being filled into the pots.

Plants were watered with deionised water when needed; no fertiliser was applied during the experiment. The pots were randomly arranged on a greenhouse table and randomised once a week. We set up 24 replicate pots of each plant species (288 pots in total) and harvested three pots of labelled and three pots of non-labelled controls of each plant species once a week over a period of 4 weeks after the initial labelling event (see below).

Foliar labelling, harvest and isotopic analysis

For foliar labelling, we prepared a 97 atom%13C, 2 atom%15N urea solution by dissolving 100 mg 99 atom%13C urea and 2 mg 98 atom%15N urea (Sigma Aldrich, Vienna, Austria) in 50 mL distilled water. To ensure good contact of the labelling solution with the leaf surface, 12·5 μL wetting agent (Neo-Wett, Kwizda, Vienna, Austria) was added. The control solution consisted of 50 mL distilled water, 102 mg unlabelled urea and 12·5 μL wetting agent. The urea concentrations are similar to those used by Schmidt & Scrimgeour (2001). Attempts to use the labelling solution without the wetting agent were not successful as solution rolled off the leaf surfaces. Labelling started after the plants developed two true leaves: The urea solution was applied with a small paint-brush on the upper and lower leaf surfaces (cotyledons were not labelled); during brushing, leaves were held with forceps. Only small amounts of the solution were applied at a time to avoid contamination of the soil. Brushing the solution was straightforward and usually took only a few seconds per plant individual. Leaves treated with adequate solution had a shiny surface, making it easy to see which leaves were already treated. Labelling was applied once a day over five consecutive days.

Three replicate pots per plant species and treatment were harvested 6 days after the beginning of labelling by carefully excavating the plants and separating roots and shoots. In the following 3 weeks, the remaining replicates were labelled once a week and three replicates per plant species and treatment were harvested 2 days after the last labelling. Over the 4 weeks of our experiment, about 80 mL of labelling solution was used (total leaf area of all labelled plants at the end of the experiment was about 1340 cm2). Roots were immediately washed free of soil and dried at 65°C for at least 24 hours. At all four harvesting dates, roots of all legume species showed rhizobia nodules. Shoots were carefully washed, scanned on a flatbed scanner (300 dpi) and afterwards dried at 65°C for at least 24 hours. Leaf area was measured using image analysing software (ImageJ for Windows, Institute of Health, Washington D.C., USA). The dried plant material was ground to a fine powder directly in 2-mL disposable reaction vials using a ball mill (Mixer Mill MM 200, Retsch, Haan, Germany) to avoid cross-contamination of samples and afterwards immediately weighed into tin capsules for isotopic analyses.

Samples were analysed by Continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry, using an elemental analyzer (EA 1110; CE Instruments, Milano, Italy) coupled to a gas isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Delta Plus; Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany). As universal standard for 15N we used atmospheric air (R = 0·003676), and for 13C we used Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite as standard (R = 0·0112372). Enrichment of plants post-labelling was calculated by subtracting, for each plant species separately, the mean atom% value of the control plants from the atom% of the labelled plants, yielding atom% excess values (APE).

Statistical analyses

Because data were not distributed normally even after testing several data transformations, we analysed them using non-parametric tests: Kruskal–Wallis-tests were used to test for significance of differences between means of two or more groups, Mann–Whitney-U-tests were used for pairwise comparisons. Spearman correlations (with Bonferroni correction to control familywise error rate) were calculated for testing the relationships between total plant dry mass and leaf area, and 15N enrichment and 13C enrichment. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 software (SPSS Inc. Headquarters, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Plant biomass production and C and N concentrations

With the exception of the grass B. media, the test plants grew well during the experiment increasing in biomass on average by 255% from week one to week four (Table S1). Species varied greatly in biomass and C and N concentrations without a clear difference between functional groups (Table S1). Early in the experiment, non-leguminous forbs had the highest biomass followed by grasses and legumes.

Isotopic enrichment after 1-week foliar labelling

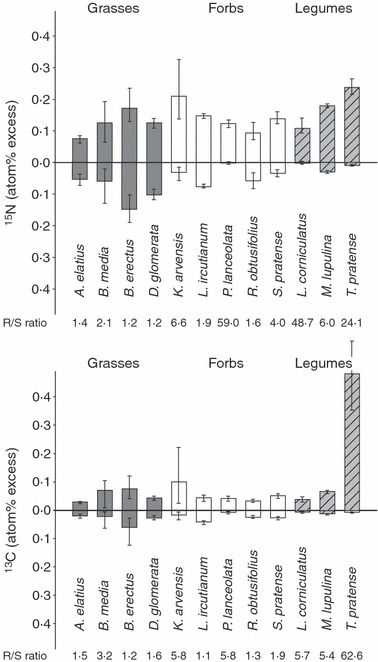

Overall, 15N isotopic enrichments after 5 labelling events were significantly higher in shoots (0·145 APE) than in roots (0·051 APE; χ2 = 26·308, d.f. = 1, P<0·001; Fig. 1). Across species, 15N enrichment differed marginally significantly in shoots (χ2 = 18·199, d.f. = 11, P=0·077) and significantly in roots (χ2 = 24·237, d.f. = 11, P=0·012; Fig. 1). Plant functional groups did not differ in their shoot 15N enrichment (χ2 = 1·636, d.f. = 2, P=0·441); however, grass roots showed a significantly higher mean 15N enrichment (0·091 APE) than non-leguminous forbs (0·038 APE; U = 33·000, d.f. = 14, P=0·008) and legumes (0·009 APE; U = 5·000, d.f. = 6, P=0·002). Legume root 15N enrichment was significantly lower than 15N enrichment in roots of non-leguminous forbs (U = 15·000, d.f. = 6, P=0·026) or grasses (U = 5·000, d.f. = 6, P=0·002). Generally, grasses showed a more even allocation of 15N enrichment between shoots and roots (shoots average: 0·125 APE; roots average: 0·091 APE) than the other functional groups where more 15N was allocated towards shoots (Fig. 1). Average 15N enrichment in shoots of non-leguminous forbs was 0·142 APE vs. 0·038 APE in roots. Legumes showed the least balanced allocation of 15N enrichment between shoots (0·163 APE) and roots (0·009 APE).

Fig. 1.

Enrichment in 15N and 13C (APE) in shoots and roots of 12 grassland species belonging to three functional groups (grasses, non-leguminous forbs, leguminous forbs) after daily foliar labelling for 5 days. Means ± Maximum/Minimum values, n = 3. The ratio between enrichments in roots and shoots (R/S ratio) is also shown for each species. [Correction added after online publication 26 Nov 2010: incorrect minus signs removed from Y-axes]

Across species, the enrichment in 13C was generally higher in shoots (0·090 APE) than in roots (0·023 APE; χ2 = 24·681, d.f. = 1, P<0·001; Fig. 1). Comparing all species, the 13C enrichment in shoots did not differ among species; however, it differed marginally among species in roots (χ2=18·176, d.f. = 11, P=0·078; Fig. 1). Functional groups did not differ in their 13C shoot enrichment but in their 13C root enrichment (χ2 = 6·623, d.f. = 2, P=0·036). With an average of 0·033 APE, grasses had similar 13C root enrichment than non-leguminous forbs (mean = 0·022 APE, U = 78·000, n = 12, P=0·758); however, 13C root enrichment in grasses was significantly higher than that of legumes (mean = 0·008 APE, U = 11·000, n = 12, P=0·019). Legumes had significantly lower 13C root enrichment than non-leguminous forbs (U = 14·000, n = 6; P=0·021) and grasses (U = 11·000, n = 6; P=0·019). Similar to 15N, the allocation of 13C in shoots and roots was more balanced in grasses than in non-leguminous forbs and legumes (Fig. 1).

Time courses of isotopic enrichments

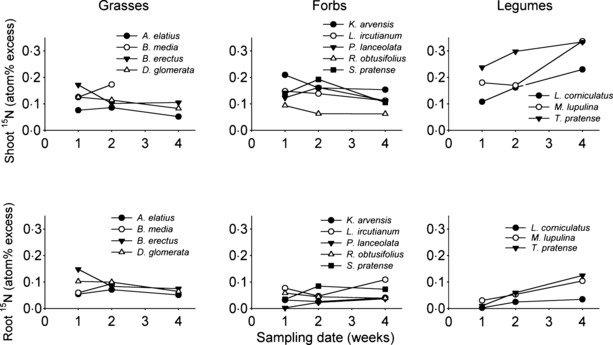

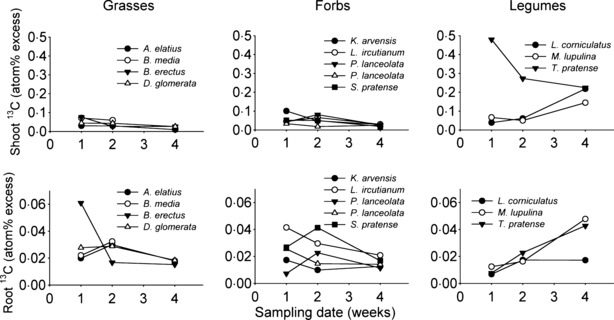

Overall, there was considerable 15N (Fig. 2) and 13C (Fig. 3) enrichment both in shoots and roots even 4 weeks after the first labelling. Averaged across species, grass shoots showed a significant decrease in 15N enrichment over the 4 weeks (χ2 = 6·102, d.f. = 2, P=0·047), while the 15N enrichment in grass roots remained unchanged over the 4 weeks (χ2 = 3·032, d.f. = 2, P=0·220; Fig. 2). Grass 13C enrichment significantly decreased over the 4 weeks in shoots (χ2 = 12·541, d.f. = 2, P=0·002) and roots (χ2 = 6·061, d.f. = 2, P=0·048; Fig. 3). Non-leguminous forb 15N enrichment in shoots and roots remained unchanged over the 4 weeks (χ2 = 3·443, d.f. = 2, P=0·179 for shoots and χ2 = 1·698, d.f. = 2, P=0·428 for roots). Non-leguminous forb 13C enrichment in shoots decreased significantly (χ2 = 10·822, d.f. = 2, P=0·004) but remained unchanged in forb roots (χ2 = 3·488, d.f. = 2, P=0·175). Legume 15N enrichment significantly increased in shoots (χ2 = 6·045, d.f. = 2, P=0·049) and roots (χ2 = 12·123, d.f. = 2, P=0·002) during the 4 weeks. Legume 13C remained unchanged in shoots (χ2 = 2·224, d.f. = 2, P=0·329) but significantly increased in roots over period of the experimental period (χ2 = 13·228, d.f. = 2, P=0·001).

Fig. 2.

Time course of the 15N enrichment in shoots and roots of 12 grassland species comprising the functional groups grasses, non-leguminous forbs and leguminous forbs during 4 weeks of foliar labelling. Means, n = 3.

Fig. 3.

Time course of the 13C enrichment in shoots and roots of 12 grassland species comprising the functional groups grasses, non-leguminous forbs and leguminous forbs during 4 weeks of foliar labelling. Means, n = 3. Note different Y-axis scales for shoots and roots.

Correlations between isotopic enrichments and plant characteristics

Across all species and dates, 15N enrichment of shoots was significantly negatively correlated with shoot dry mass, while 15N enrichment of roots was significantly positively correlated with root dry mass (Table 1). Across all species and dates, only shoot 13C enrichment was significantly negatively correlated with either shoot dry mass or leaf area, while root 13C was unrelated to root dry mass. Among functional groups, both shoot and root 15N enrichments were significantly positively correlated with shoot 13C or root 13C, respectively (Table 1). Only non-leguminous forbs showed statistically significant correlations between 15N or 13C enrichment and either dry mass or leaf area, while isotope enrichments in grasses and legumes were unrelated to the measured characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Spearman correlations between 15N and 13C atom percent excess (APE) isotopic enrichments and plant characteristics across species and sampling dates. Significant correlations (P < 0·005) after Bonferroni adjustments are in bold

| Across species | Grasses | Forbs | Legumes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | rs | rs | rs | rs |

| Shoot 15N | ||||

| vs. shoot13C | 0·823 | 0·880 | 0·629 | 0·792 |

| vs. shoot dry mass | −0·498 | −0·122 | −0·588 | −0·073 |

| vs. leaf area | −0·597 | −0·231 | −0·597 | −0·080 |

| Shoot 13C | ||||

| vs. shoot dry mass | −0·466 | −0·236 | −0·403 | 0·197 |

| vs. leaf area | −0·487 | −0·301 | −0·420 | −0·197 |

| Root 15N | ||||

| vs. root13C | 0·672 | 0·622 | 0·560 | 0·921 |

| vs. root dry mass | 0·294 | −0·080 | −0·131 | 0·186 |

| Root 13C | ||||

| vs. root dry mass | −0·012 | −0·221 | −0·225 | −0·110 |

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that brushing 15N and 13C urea onto the leaf surface of a dozen of grass, non-leguminous forb and legume species is a feasible method for in situ dual-labelling of herbaceous plant species. Moreover, the positive correlation between 15N and 13C enrichment for both shoots and roots indicates that the tested species can successfully be labelled with the two isotopes. In contrast to other studies in which stable isotope solutions were sprayed onto the leaf surface (Below et al. 1985; Palta et al. 1991; Schmidt & Scrimgeour 2001; Yasmin, Cadisch, & Baggs 2006), our brushing method has the advantage of being more controlled, precise and targeted. Therefore, selected plant species, even in dense stands, can be labelled without unintentionally contaminating other plants or soil. Further, most of the previous studies on foliar labelling were conducted on crop species (maize: Below et al. 1985; Schmidt & Scrimgeour 2001; wheat: Palta et al. 1991; chickpea: Yasmin, Cadisch, & Baggs 2006), the present study has established that grassland species with much lower growth rates can also be successfully labelled via foliar feeding.

Our expectation that functional groups would significantly differ in their isotopic enrichments because of their morphological differences was only partly met. While isotopic enrichments in shoots were similar between functional groups, the allocation of 15N tracers into roots was highest in grasses followed by forbs and legumes, while 13C enrichment was similar in grasses and forbs, although higher than in legumes. This indicates that functional groups mainly differed in their allocation of the labelled urea acquired through leaves within the plant. A higher 15N and 13C allocation into the root systems of the four grass species compared with the non-leguminous forbs and legumes may be explained by the different root system of grasses (Fitter 1987) comprising more homogenous fine roots and a lower root/shoot ratio than non-leguminous forbs and legumes (root/shoot ratios based on dry matter across all harvests were 0·44, 0·65 and 0·52 for grasses, forbs and legumes, respectively). This would mean a greater nutrient allocation to below-ground plant parts and therefore greater 15N and 13C allocation to roots. Moreover, grass root systems usually also have less ligneous structures and higher turnover rates than other root systems, leading to a more rapid incorporation of C and N into root systems (Gross, Maruca, & Pregitzer 1992; Eissenstat 2000). This is also supported by the study of Hertenberger & Wanek (2004) showing that the 15N signal after commencement of labelling with stem infiltration reached the roots of the grass L. perenne after 20 hours, but only after 26 hours in the forb Centaurea jacea. Despite higher root biomass than shoot biomass, the forb P. lanceolata and the legume L. corniculatus allocated only very small amounts of 15N and 13C into their roots, indicating very little turnover of the rather course root systems of these species.

Considering the more general patterns of 15N enrichment, species allocated on average 74%15N into shoots, which indicates that a substantial amount was transported into their root systems. The 26% isotope allocation into roots is in contrast to other studies mainly of crop plants suggesting that only a small fraction of the label taken up foliarly was transferred into roots (Palta et al. 1991; Russell & Fillery 1996; McNeill, Zhu, & Fillery 1997; Schmidt & Scrimgeour 2001; Khan, Peoples, & Herridge 2002). These contrasting findings perhaps reflect morphological and physiological differences between grassland plants and crops manifested by different growth patterns and a higher allocation of resources into the root system by grassland plants. Species of less productive grasslands are expected to have lower growth rates as well as greater partitioning of photosynthates and nutrients to root systems for effective water and nutrient uptake under conditions of competition and stress (Chapin 1980). In contrast, crop plants are bred for fast growth, which is mainly the result from biomass allocation to leaf biomass but not into root systems.

Our finding of a considerably lower 13C enrichment than 15N enrichment in shoots and roots across all species is consistent with other studies (Schmidt & Scrimgeour 2001), reflecting the facts that urea [CO(NH2)2] provides two atoms of N for each atom of C and that some 13C is lost through respiration (Lakkineni et al. 1995). Nevertheless, it was still interesting to see that 13C in urea solution applied onto the leaf surface can enter the plant tissue and is incorporated into the root system. Schmidt & Scrimgeour (2001) discuss some evidence suggesting that urea-derived C and atmospheric C, once taken up by leaves, are assimilated and translocated in a similar fashion. Another possible reason for restricted 13C enrichment is the over-supply of N to the plant, which may lead to reduced carbohydrate accumulation (Gooding & Davies 1992); however, this is unlikely in our system as the soil nutrient concentrations were only moderate. Among legumes, only 7%15N of the whole-plant isotopic signal were allocated into roots, suggesting that rhizobia associated with all tested legume species might have diluted the 15N signal in roots. The 13C enrichment of legume roots was perhaps lower than that of other plants because of the contribution of C stored in existing root nodule biomass before labelling commenced (nodule biomass was not measured separately in this study). An exception to the 13C enrichment patterns was the legume T. pratense that showed a four-times higher 13C enrichment in shoot than all other species. We explain this pattern by the small growth and biomass increase of this species, leading to an accumulation of the isotopic label in the shoots with only little transfer to the roots. Moreover, in stable isotope studies, there is always the possibility of sample contamination, but it is unlikely that all three sample replicates were contaminated.

Persistance of the labelling signal

No data on the persistence of the labelling signal after foliar feeding are available for grassland plant species. With the proposed method, isotopic enrichment levels in shoots and roots were generally low for both 15N and 13C (<1% APE) and these levels either decreased (e.g. grass shoots), increased (e.g. legume shoots) or remained unchanged (e.g. forb shoots) over 4 weeks with re-labelling each week. Enrichment levels observed here are similar to those achieved in the native forb C. jacea or the grass Lolium perenne using the leaf tipping method measured 48 hours after labelling (Hertenberger & Wanek 2004). To increase the isotopic signal in the tested plant species, a higher concentration of the urea solution would be necessary; however, this could increase the risk of causing leaf burning damage (Bremner 1995). This need to use low urea concentrations also limits the maximum 13C enrichment achievable with urea leaf-feeding. More than one labelling a week would probably sustain a higher isotopic signal over a longer period as indicated by the negative correlation between isotopic signal and shoot mass or leaf area, however, whether this varies among species requires further testing.

In conclusion, the simple dual-labelling method tested in the current study appears to be a feasible alternative to growing plants in enriched soil and gas-tight laboratory chambers or using portable labelling enclosures. Together with other recent developments in isotope labelling (e.g. plant seed labelling, Carlo, Tewksbury, & Martinez del Rio 2009), the current method opens new avenues for studying ecological interactions in situ in plant communities. In particular, the method can be used to identify linkages between specific plants in a community and soil organisms and to quantify the contributions of individual plant species to soil processes linked to C and N inputs (e.g. Orwin et al. 2010; Witt & Setälä 2010).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Barbara Heiner, Lina Weissengruber, Lisa Kargl and Norbert Schuller for help during harvests. This study was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): project no. P20171-B16.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Table S1. Dry mass, N and C concentration of shoots and roots of 12 native grassland species comprising the functional groups grasses, non-leguminous forbs and leguminous forbs after one week and after four weeks of foliar labelling (label.).

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

References

- Below FE, Crafts-Brandner SJ, Harper JE, Hageman RH. Uptake, distribution and remobilization of 15N-labeled urea applied to maize canopies. Agronomy Journal. 1985;77:412–415. [Google Scholar]

- Berg JD, Hendrix PF, Cheng WX, Dillard AL. A labeling chamber for 13C enrichment of plant tissue for decomposition studies. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment. 1991;34:421–425. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JM. Recent research on problems in the use of urea as a nitrogen fertilizer. Fertilizer Research. 1995;42:321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Bromand B, Whalen JK, Janzen HH, Schjoerring JK, Ellert BH. A pulse-labelling method to generate C-13-enriched plant materials. Plant and Soil. 2001;235:253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Carlo TA, Tewksbury JJ, Martinez del Rio C. A new method to track seed dispersal and recruitment using 15N isotope enrichment. Ecology. 2009;90:3516–3525. doi: 10.1890/08-1313.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin FSI. The mineral nutrition of wild plants. Annual Reviews of Ecology and Systematics. 1980;11:233–260. [Google Scholar]

- Eissenstat D. Root structure and function in an ecological context. New Phytologist. 2000;148:353–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Naggar A, El-Araby A, de Neergaard A, Hogh-Jensen H. Crop responses to N-15-labelled organic and inorganic nitrogen sources. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems. 2008;80:49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fitter AH. Functional significance of root morphology. New Phytologist. 1987;106:87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Gooding MJ, Davies WP. Foliar urea fertilization of cereals: a review. Fertilizer Research. 1992;32:209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gross KL, Maruca D, Pregitzer KS. Seedling growth and root morphology of plants with different life-histories. New Phytologist. 1992;120:535–542. [Google Scholar]

- Herman PMJ, Middelburg JJ, Widdows J, Lucas CH, Heip CHR. Stable isotopes as trophic tracers: combining field sampling and manipulative labelling of food resources for macrobenthos. Marine Ecology - Progress Series. 2000;204:79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hertenberger G, Wanek W. Evaluation of methods to measure differential N-15 labeling of soil and root N pools for studies of root exudation. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2004;18:2415–2425. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood-Nowotny R, Knols BGJ. Stable isotope methods in biological and ecological studies of arthropods. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 2007;124:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Khan WDF, Peoples MB, Herridge DF. Quantifying below-ground nitrogen of legumes – 1. Optimising procedures for N-15 shoot-labelling. Plant and Soil. 2002;245:327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Lakkineni KC, Sivasankar A, Kumar PA, Nair TVR, Abrol YP. Carbon dioxide assimilation in urea-treated wheat leaves. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 1995;18:2213–2217. [Google Scholar]

- Leake JR, Ostle NJ, Rangel-Castro JI, Johnson D. Carbon fluxes from plants through soil organisms determined by field 13CO2 pulse-labelling in an upland grassland. Applied Soil Ecology. 2006;33:152–175. [Google Scholar]

- Martens H, Alphei J, Schaefer M, Scheu S. Millipedes and earthworms increase the decomposition rate of N-15-labelled winter rape litter in an arable field. Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies. 2001;37:43–51. doi: 10.1080/10256010108033280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill AM, Zhu CY, Fillery IRP. Use of in situ N-15-labeling to estimate the total below-ground nitrogen of pature legumes in intact soil-plant systems. Austrialian Journal of Agricultural Research. 1997;48:295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Michener RH, Kaufman L. Stable isotope ratios as tracers in marine food webs: an update. In: Michener R, Lajtha K, editors. Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science. 2nd edn. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2007. pp. 238–282. [Google Scholar]

- Orwin KH, Buckland SM, Johnson D, Turner BL, Smart S, Oakley S, Bardgett RD. Linkages of plant traits to soil properties and the functioning of temperate grassland. Journal of Ecology. 2010;98:1074–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Palta JA, Fillery IRP, Mathews EL, Turner NC. Leaf feeding of [N-15] urea for labeling wheat with nitrogen. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research. 1991;18:627–636. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen J, Eriksen J, Jensen ES, Esbensen KH, Hogh-Jensen H. In situ carbon and nitrogen dynamics in ryegrass-clover mixtures: transfers, deposition and leaching. Soil Biology & Biochemistry. 2007;39:804–815. [Google Scholar]

- Russell CA, Fillery IRP. In situ N-15 labelling of lupin below-ground biomass. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research. 1996;47:1035–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O, Scrimgeour CM. A simple urea leaf-feeding method for the production of 13C and 15N labelled plant material. Plant and Soil. 2001;229:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Seeber J, Langel R, Meyer E, Traugott M. Dwarf shrub litter as a food source for macro-decomposers in alpine pastureland. Applied Soil Ecology. 2009;41:178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Simard SW, Perry DA, Jones MD, Myrold DD, Durall DM, Molina R. Net transfer of carbon between ectomycorrhizal tree species in the field. Nature. 1997;288:579–582. [Google Scholar]

- Subke JA, Vallack HW, Magnusson T, Keel SG, Metcalfe DB, Högberg P, Ineson P. Short-term dynamics of abiotic and biotic soil (CO2)-C-13 effluxes after in situ (CO2)-C-13 pulse labelling of a boreal pine forest. New Phytologist. 2009;183:349–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichern F, Mayer J, Joergensen RG, Müller T. Rhizodeposition of C and N in peas and oats after 13C-15N double labelling under field conditions. Soil Biology & Biochemistry. 2007;39:2527–2537. [Google Scholar]

- Witt C, Setälä H. Do plant species of different resource qualities form dissimilar energy channels below-ground? Applied Soil Ecology. 2010;44:270–278. [Google Scholar]

- Yasmin K, Cadisch G, Baggs EM. Comparing 15N-labelling techniques for enriching above- and below-ground components of the plant-soil system. Soil Biology & Biochemistry. 2006;38:397–400. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.