Abstract

Peritoneal adhesions describe a condition in which pathological bonds form between the omentum, the small and large bowels, the abdominal wall, and other intra-abdominal organs. Different classification systems have been proposed, but they do not resolve the underlying problem of ambiguity in the quantification and definition of adhesions. We therefore propose a standardized classification system of adhesions to universalize their definition based on the macroscopic appearance of adhesions and their diffusion to different regions of the abdomen. By scoring with these criteria, the peritoneal adhesion index (PAI) can range from 0 to 30, unambiguously specifying precise adhesion scenarios. The standardized classification and quantification of adhesions would enable different studies to more meaningfully integrate their results, thereby facilitating a more comprehensive approach to the treatment and management of this pathology.

Keywords: Adhesions, Classification, PAI, Peritoneal, Abdominal, Occlusion, Surgery, Treatment, Prevention

Article

Peritoneal adhesions are pathological bonds that typically form between the omentum, the small and large bowels, the abdominal wall, and other intra-abdominal organs. These bonds may be a thin film of connective tissue, a thick fibrous bridge containing blood vessels and nerve tissue, or a direct adhesion between two organ surfaces [1-3].

Depending on the etiology, peritoneal adhesions may be classified as congenital or acquired (post-inflammatory or post-operative) [4]. Some researchers assert that adhesions could also be classified in three major groups: adhesions formed at operative sites, adhesions formed de novo at non-operative sites, and adhesions formed after the lysis of previous adhesions [5]. Diamond et al. distinguished types 1 and 2 of postoperative peritoneal adhesions. Type 1, or de novo adhesion formation, involves adhesions formed at sites that did not have previous adhesions, including Type 1A (no previous operative procedure at the site of adhesion) and Type 1B (previous operative procedures at the site of adhesion). Type 2 involves adhesion reformation, with two separate subtypes: Type 2A (no operative procedure other than adhesiolysis at the site of adhesion) and Type 2B (other operative procedures at the site of adhesions) [6]. In 1990, Zhulke et al. proposed a classification of adhesions based on their macroscopic appearance, which has since been used expressly for experimental purposes [7]. These different classifications have no impact on the underlying problem of post-operative/post-inflammatory adhesions, which can be dramatic. Moreover these classification systems do not engender an unequivocal system of quantification and definition. Each surgeon defines adhesions on an individual basis contingent on the surgeon’s own experience and capability. At present, it is not possible to analytically standardize adhesions, even if such cases are a surgeon’s primary focus. The prevalence of adhesions following major abdominal procedures has been evaluated to be 63%-97% [8-12]. Laparoscopic procedures compared to open surgery have not demonstrated to significantly reduce the total number of post-operative adhesions [13-17]. Adhesions are a major source of morbidity and are the most common cause of intestinal obstruction [18,19], secondary female infertility, and ectopic gestation [20,21]. They may also cause chronic abdominal and pelvic pain [3,22,23]. Adhesive small bowel obstruction is the most serious consequence of intra-abdominal adhesions. Colorectal surgery has proven to be the most common surgical cause of intra-abdominal adhesions. Among open gynecological procedures, ovarian surgery was associated with the highest rate of readmission due to subsequent adhesions (7.5/100 initial operations) [24]. Retrospective studies have shown that 32%-85% of patients who require secondary abdominal surgery have adhesion-related intestinal obstruction. Experimental and clinical studies are not in agreement regarding the different rates of adhesion reformation following adhesiolysis performed via laparotomy or laparoscopy [25-27]. Guidelines have been published regarding the management of adhesive small bowel obstruction by the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) [28].

Adhesions require highly involved surgical intervention and are a significant burden to health care systems. In the United States, an epidemiological study demonstrated that in 1988, 282,000 hospital admissions were attributable to adhesion-related disorders, and the cost of in-patient adhesiolysis procedures reached $1.18 billion [29]. Another study published in 1994, reported that 1% of all admissions in the United States involved adhesiolysis, costing $1.33 billion [30]. Adhesions and their associated complications have piqued both medical and legal interest in recent years [31]. Successful medical/legal claims include cases of bowel perforation following laparoscopic resolution of adhesion, delays in the diagnosis of adhesion obstruction of the small bowel, infertility resulting from adhesions, and visceral pain [31,32]. Currently, there is no effective method for preventing adhesion formation or reformation [33]. A more comprehensive understanding of the pathogenesis of adhesion formation at cellular and molecular levels is needed to streamline preventative treatment strategies [10].

The pathogenesis of adhesion formation involves three important trauma-induced processes: (I) inhibition of the fibrinolytic and extracellular matrix degradation systems [34,35]; (II) induction of an inflammatory response involving the production of cytokines and growth factor-β (TGF-β1), a key regulator of tissue fibrosis [36-38]; and (III) induction of tissue hypoxia following interruption of blood delivery to mesothelial cells and sub-mesothelial fibroblasts, leading to increased expression of hypoxia-induced factor-1α [39,40] and vascular endothelial growth factor, responsible for collagen formation and angiogenesis [31,41].

Several trials have examined the effects of systemic and local application of a variety of drugs, including steroids [41,42], non-selective and selective cyclooxygenase inhibitors [43-47], heparin [48-50], 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) [51], and tissue-plasminogen activator [52]. Different theoretical approaches involving, for example, growth factors or the neurokinin-1 receptor, have also been tested. Further, the use of natural agents such as pollen and honey or cold saline solutions has been explored in an effort to reduce adhesion rates [53,54].

Local molecular therapies, including recombinant antibodies and protein, have been employed with moderate success [31]; these therapeutic agents work by correcting aberrant molecular pathways involved in adhesion formation [31]. Local molecular therapy is inherently limited; therefore an alternative strategy using gene therapy has recently been employed to correct molecular aberrations induced by surgical trauma [31]. In five studies based on rat models, different vectors were used to express therapeutic nucleic acids (transgenes or small interfering RNAs) in peritoneal tissue [31,40,55-59].

However, no method has distinguished itself as the optimal means of preventing adhesion formation [59]. Current preventive approaches range from the use of physical barriers to the administration of pharmacological agents, recombinant proteins and antibodies, and gene therapy, yet they have all failed to consistently yield satisfactory results. Single therapeutic strategies are typically unsuccessful in preventing peritoneal adhesions due to the multi-factorial nature of adhesion pathogenesis. Extensive literature on the subject demonstrates both the complexity of the issue and the myriad resources allocated to this condition, yet few interdisciplinary studies have been conducted involving experts from different fields. At this time the medical community only recognizes the “tip of the iceberg” and will continue treating the condition inadequately until it is more comprehensively explored.

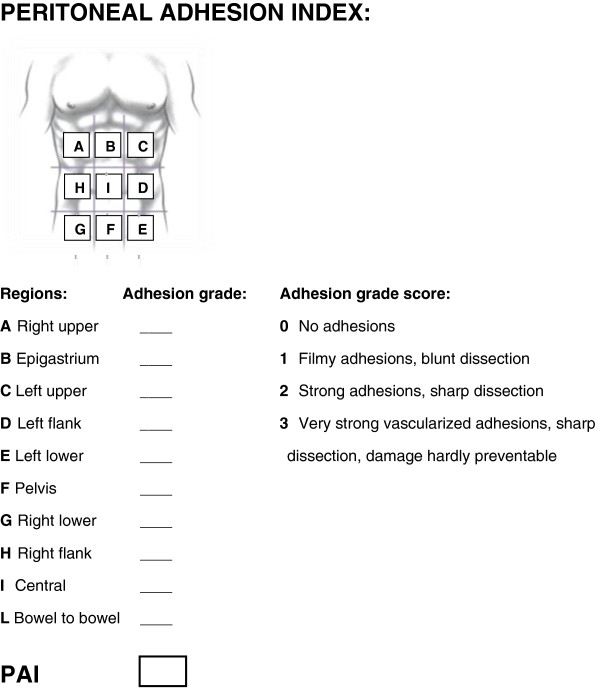

We are in agreement with Hellebrekers et al. and believe that additional prospective studies must be conducted to examine adhesion formation in relation to factors of inflammation, coagulation, and fibrinolysis. To more effectively integrate the findings of different studies, specific attention should be paid to uniformity of measurement (what, where, and when to measure) [60]. We therefore suggest a regimented classification system for adhesions in an effort to standardize their definition and subsequent analysis. In this way, different surgeons in different treatment centers can more effectively evaluate patients and compare their conditions to past evaluations using a universal classification system (Figure 1). This classification is based on the macroscopic appearance of adhesions and their extent to the different regions of the abdomen. Using specific scoring criteria, clinicians can assign a peritoneal adhesion index (PAI) ranging from 0 to 30, thereby giving a precise description of the intra-abdominal condition. Standardized classification and quantification of adhesions would enable researchers to integrate the results of different studies to more comprehensively approach the treatment and management of adhesion-related pathology.

Figure 1.

Peritoneal adhesion index: by ascribing to each abdomen area an adhesion related score as indicated, the sum of the scores will result in the PAI.

Furthermore, as asserted by other researchers [53], we must encourage greater collaboration among basic, material, and clinical sciences. Surgery is progressively becoming more dependent on the findings of research in the basic sciences, and surgeons must contribute by practicing research routinely in a clinical setting. To further advance surgical techniques, we must better understand the physiopathology of surgically induced conditions.

Competing interests

All authors declare to have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

FCo, LA, FCa: Conception of the score, literature search and manuscript production. RM, LC, EP, PB, MS, SDS: literature search and analysis. MC, MGC, DL, MP: practical evaluation of the score. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Federico Coccolini, Email: federico.coccolini@gmail.com.

Luca Ansaloni, Email: lansaloni@hpg23.it.

Roberto Manfredi, Email: rmanfredi@hpg23.it.

Luca Campanati, Email: lcampanati@hpg23.it.

Elia Poiasina, Email: epoiasina@hpg23.it.

Paolo Bertoli, Email: bpaolo@hpg23.it.

Michela Giulii Capponi, Email: giulii@inwind.it.

Massimo Sartelli, Email: m.sartelli@virgilio.it.

Salomone Di Saverio, Email: salo75@inwind.it.

Michele Cucchi, Email: mcucchi@alice.it.

Daniel Lazzareschi, Email: dvlazzareschi@gmail.com.

Michele Pisano, Email: mpisano@hpg23.it.

Fausto Catena, Email: faustocatena@gmail.com.

References

- Diamond MP, Freeman ML. Clinical implications of postsurgical adhesions. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:567–576. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arung W, Meurisse M, Detry O. Pathophysiology and prevention of postoperative peritoneal adhesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4545–4553. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i41.4545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman H, Gabella G, Davis MSc C, Mutsaers SE, Boulos P, Laurent GJ, Herrick SE. Presence and distribution of sensory nerve fibers in human peritoneal adhesions. Ann Surg. 2001;234:256–261. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis H. The clinical significance of adhesions: focus on intestinal obstruction. Eur J Surg Suppl. 1997;577:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouly JL, Seak-San S. In: Peritoneal surgery. DiZerega GS, editor. Springer, New York; 2000. Adhesions: laparoscopy versus laparotomy; pp. 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond MP. Reduction of de novo postsurgical adhesions by intraoperative precoating with sepracoat (HAL-C) solution: a prospective, randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled multicenter study. The sepracoat adhesion study group. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:1067–1074. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zühlke HV, Lorenz EM, Straub EM, Savvas V. Pathophysiology and classification of adhesions. Langenbecks Arch Chir Verh Dtsch Ges Chir. 1990;Suppl 2:1009–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MC, Wilson MS, van Goor H, Moran BJ, Jeekel J, Duron JJ, Menzies D, Wexner SD, Ellis H. Adhesions and colorectal surgery - call for action. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9(Suppl 2):66–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liakakos T, Thomakos N, Fine PM, Dervenis C, Young RL. Peritoneal adhesions: etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical significance. Recent advances in prevention and management. Dig Surg. 2001;18:260–273. doi: 10.1159/000050149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong YC, Laird SM, Li TC, Shelton JB, Ledger WL, Cooke ID. Peritoneal healing and adhesion formation/reformation. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:556–566. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kössi J, Salminen P, Rantala A, Laato M. Population-based study of the surgical workload and economic impact of bowel obstruction caused by postoperative adhesions. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1441–1444. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies D, Ellis H. Intestinal obstruction from adhesions–how big is the problem? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990;72:60–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutt CN, Oniu T, Schemmer P, Mehrabi A, Büchler MW. Fewer adhesions induced by laparoscopic surgery? Surg Endosc. 2004;18:898–906. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krähenbühl L, Schäfer M, Kuzinkovas V, Renzulli P, Baer HU, Büchler MW. Experimental study of adhesion formation in open and laparoscopic fundoplication. Br J Surg. 1998;85:826–830. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard CL, Clements RH, Nanney L, Davidson JM, Richards WO. Adhesion formation is reduced after laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:10–13. doi: 10.1007/s004649900887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymeneas G, Theodosopoulos T, Stamatiadis A, Kourias E. A comparative study of postoperative adhesion formation after laparoscopic vs open cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:41–43. doi: 10.1007/s004640000269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinaro F, Kaselas C, Lacreuse I, Moog R, Becmeur F. Postoperative intestinal obstruction after laparoscopic versus open surgery in the pediatric population: A 15-year review. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2009;19:160–162. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra FR, Nieuwenhuijzen M, Reijnen MM, van Goor H. Recent clinical developments in pathophysiology, epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of intra-abdominal adhesions. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2000;232:52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jaroudi D, Tulandi T. Adhesion prevention in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:360–367. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200405000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpay Z, Saed GM, Diamond MP. Female infertility and free radicals: potential role in adhesions and endometriosis. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006;13:390–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimbos-Kemper TC, Trimbos JB, van Hall EV. Adhesion formation after tubal surgery: results of the eighth-day laparoscopy in 188 patients. Fertil Steril. 1985;43:395–400. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)48438-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresch AJ, Seifer DB, Sachs LB, Barrese I. Laparoscopy in 100 women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:672–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton C, MacDonald R. Laser laparoscopic adhesiolysis. J Gynecol Surg. 1990;6:155–159. doi: 10.1089/gyn.1990.6.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis H, Moran BJ, Thompson JN, Parker MC, Wilson MS, Menzies D, McGuire A, Lower AM, Hawthorn RJ, O’Brien F, Buchan S, Crowe AM. Adhesion-related hospital readmissions after abdominal and pelvic surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 1999;353:1476–1480. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond MP, Wexner SD, DiZerega GS. et al. Adhesion prevention and reduction: current status and future recommendations of a multinationalinter-disciplinary consensus conference. Surg Innov. 2012;17:183–188. doi: 10.1177/1553350610379869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEntee G, Pender D, Mulvin D, McCullough M, Naeeder S, Farah S, Badurdeen MS, Ferraro V, Cham C, Gillham N. Current spectrum of intestinal obstruction. Br J Surg. 1987;74:976–980. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800741105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prushik SG, Stucchi AF, Matteotti R, Aarons CB, Reed KL, Gower AC, Becker JM. Open adhesiolysis is more effective in reducing adhesion reformation than laparoscopic adhesiolysis in an experimental model. Br J Surg. 2010;97:420–427. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catena F, Di Saverio S, Kelly MD, Biffl WL, Ansaloni L, Mandalà V. et al. Bologna guidelines for diagnosis and management of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO): 2010 evidence-based guidelines of the world society of emergency surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-6-5. 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray NF, Larsen JW, Stillman RJ, Jacobs RJ. Economic impact of hospitalizations for lower abdominal adhesiolysis in the United States in 1988. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;176:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray NF, Denton WG, Thamer M, Henderson SC, Perry S. Abdominal adhesiolysis: inpatient care and expenditures in the United States in 1994. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(97)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atta MH. Prevention of peritoneal adhesions: a promising role for gene therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:5049–5058. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i46.5049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis H, Crowe A. Medico-legal consequences of post-operative intra-abdominal adhesions. Int J Surg. 2009;7:187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman DM, Trout JR, Diamond MP. The rates of adhesion adhesion development and the effects of crystalloid solutions on adhesion development in pelvic surgery. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:702–711. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmdahl L, Eriksson E, Eriksson BI, Risberg B. Depression of peritoneal fibrinolysis during operation is a local response to trauma. Surgery. 1998;123:539–544. doi: 10.1067/msy.1998.86984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson ML, Bergström M, Eriksson E, Risberg B, Holmdahl L. Tissue markers as predictors of postoperative adhesions. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1549–1554. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmdahl L, Kotseos K, Bergström M, Falk P, Ivarsson ML, Chegini N. Overproduction of transforming growth factorbeta1 (TGF-beta1) is associated with adhesion formation and peritoneal fibrinolytic impairment. Surgery. 2001;129:626–632. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.113039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chegini N, Kotseos K, Zhao Y, Bennett B, McLean FW, Diamond MP, Holmdahl L, Burns J. Differential expression of TGF-beta1 and TGF-beta3 in serosal tissues of human intraperitoneal organs and peritoneal adhesions. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1291–1300. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.6.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong YC, Shelton JB, Laird SM, Li TC, Ledger WL, Cooke ID. Peritoneal fluid concentrations of matrix metalloproteinase- 9, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, and transforming growth factor-beta in women with pelvic adhesions. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1168–1175. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinas CR, Campo R, Elkelani OA, Binda MM, Carmeliet P, Koninckx PR. Role of hypoxia inducible factors 1alpha and 2alpha in basal adhesion formation and in carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum-enhanced adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery in transgenic mice. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(Suppl 2):795–802. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00779-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura T, Schmokel H, Hubbell JA. RNA interference targeting hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha reduces post-operative adhesions in rats. J Surg Res. 2007;141:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill RA, Wang JH, Soohkai S, Redmond HP. Mast cells facilitate local VEGF release as an early event in the pathogenesis of postoperative peritoneal adhesions. Surgery. 2006;140:108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avsar FM, Sahin M, Aksoy F, Avsar AF, Akoz M, Hengirmen S, Bilici S. Effects of diphenhydramine HCl and methylprednisolone in the prevention of abdominal adhesions. Am J Surg. 2001;181(6):512–515. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(01)00617-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin M, Cakir M, Avsar FM, Tekin A, Kucukkartallar T, Akoz M. The effects of anti-adhesion materials in preventing postoperative adhesion in abdominal cavity (anti-adhesion materials for postoperative adhesions) Inflammation. 2007;30(6):244–249. doi: 10.1007/s10753-007-9043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzii L, Marana R, Brunetti L, Margutti F, Vacca M, Mancuso S. Postoperative adhesion prevention with low-dose aspirin: effect through the selective inhibition of thromboxane production. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(6):1486–1489. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.6.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SH, Kim JK, Song KS, Noh SM, Ghil SH, Yuk SH, Lee JH. Prevention of postsurgical tissue adhesion by anti-inflammatory drug-loaded pluronic mixtures with sol–gel transition behavior. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;72(3):306–316. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers KE, Johns DB, Girgis W, diZerega GS. Prevention of adhesion formation with intraperitoneal administration of tolmetin and hyaluronic acid. J Invest Surg. 1997;10(6):367–373. doi: 10.3109/08941939709099600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldemir M, Ozturk H, Erten C, Buyukbayram H. The preventive effect of rofecoxib in postoperative Intraperitoneal adhesions. Acta Chir Belg. 2004;104(1):97–100. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2003.11978403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa M, Girgis W, diZerega GS. Inhibition of postsurgical adhesions in a standardized rabbit model: II. Intraperitoneal treatment with heparin. Int J Fertil. 1991;36(5):296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlay J, Ozer Y, Isik B, Kargici H. Comparative effectiveness of several agents for preventing postoperative adhesions. World J Surg. 2004;28(7):662–665. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-6825-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsak CK, Satar S, Akcam T, Satar D, Sungur I. Effectiveness of treatment to prevent adhesions after abdominal surgery: an experimental evaluation in rats. Adv Ther. 2007;24(4):796–802. doi: 10.1007/BF02849972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons CB, Cohen PA, Gower A, Reed KL, Leeman SE, Stucchi AF. et al. Statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) decrease postoperative adhesions by increasing peritoneal fibrinolytic activity. Ann Surg. 2007;245:176–184. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000236627.07927.7c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr PJ, Vemer HM, Brommer EJ, Willemsen WN, Veldhuizen RW, Rolland R. Prevention of postoperative adhesions by tissuetype plasminogen activator (t-PA) in the rabbit. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1990;37(3):287–291. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(90)90037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celeplı S, Kismet K, Kaptanoğlu B, Erel S, Ozer S, Celeplı P. et al. The effect of oral honey and pollen on postoperative intraabdominal adhesions. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2011;22:65–72. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2011.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang CC, Chou TH, Lin GS, Yen ZS, Lee CC, Chen SC. Peritoneal infusion with cold saline decreased postoperative intra-abdominal adhesion formation. World J Surg. 2010;34:721–727. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atta HM, Al-Hendy A, El-Rehany MA, Dewerchin M, Abdel Raheim SR, Abdel Ghany H, Fouad R. Adenovirusmediated overexpression of human tissue plasminogen activator prevents peritoneal adhesion formation/reformation in rats. Surgery. 2009;146:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Leung JC, Cheung JS, Chan LY, Wu EX, Lai KN. Non-viral Smad7 gene delivery and attenuation of postoperative peritoneal adhesion in an experimental model. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1323–1335. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Li QF, Liu HJ, Li R, Wu CT, Wang LS. Sphingosine kinase 1 gene transfer reduces postoperative peritoneal adhesion in an experimental model. Br J Surg. 2008;95:252–258. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HJ, Wu CT, Duan HF, Wu B, Lu ZZ, Wang L. Adenoviral- mediated gene expression of hepatocyte growth factor prevents postoperative peritoneal adhesion in a rat model. Surgery. 2006;140:441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochhausen C, Schmitt VH, Planck CN, Rajab TK, Hollemann D, Tapprich C, Current strategies and future perspectives for Intraperitoneal adhesion prevention. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hellebrekers BW, Kooistra T. Pathogenesis of postoperative adhesion formation. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1503–1516. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]