Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was (1) to compare family communication, decision support (i.e., supporting the patient in making decisions), self-efficacy in patient-physician communication (i.e., patients’ confidence level in communicating with physicians), and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) between Chinese- and Korean-American breast cancer survivors (BCS), and (2) to investigate how family communication, decision support, and self-efficacy in patient-physician communication influences HRQOL for Chinese- and Korean-American BCS.

Methods

A cross-sectional design was used. A total of 157 Chinese- (n=86) and Korean-American (n=71) BCS were recruited from the California Cancer Surveillance Program and area hospitals in Los Angeles County. The Chronic Care Model was utilized.

Results

Chinese- and Korean-Americans showed a significant difference in the decision support only. Self-efficacy in patient-physician communication was directly associated with HRQOL for Chinese-Americans, whereas for Korean-Americans, family communication was related to HRQOL. The mediating effects of decision support and self-efficacy in physician-patient communication in the relationship between family communication and HRQOL were observed for Chinese-Americans only. Multiple group analysis demonstrated that the structural paths varied between Chinese- and Korean-American BCS.

Conclusions

Our results provide insight into the survivorship care of Chinese- and Korean-American BCS, allowing a better understanding of communication among survivors, family, and healthcare providers. Communication skills to manage conflict and attain consensus among them under the cultural contexts are essential to improve HRQOL for BCS.

Keywords: Asian-American, Breast cancer survivors, Decision support, Efficacy in patient-physician communication, Family communication, Health-related quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Asian-Americans are one of the largest and fastest growing ethnic minority groups in the US [1]. In this group, breast cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death [2]. According to the American Cancer Society [2], the five-year survival rate of Asian-Americans is now 90.7%. Given the increasing number of Asian-American breast cancer patients [2], survivorship experiences and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) may be important outcomes to assess the impact of cancer among Asian-American breast cancer survivors (BCS).

Among Asian Americans, we are specifically interested in studying Chinese- and Korean-Americans. They have emigrated from a close geographical proximity and share common cultural aspects, such as Confucian and collectivistic values. However, they also have different cultures, languages, attitudes, and immigration histories [3–5]. For example, many early Chinese immigrants arrived in the US in the mid to late-19th Century, leaving their families behind in China, whereas a majority of Korean immigrants arrived in the US with their family members after the 1965 Immigration Act. The median age of Korean-Americans is relatively low compared to Chinese-Americans, given that the Chinese group has a longer history of immigration than the Korean group [6, 7]. Thus, the inclusion of these two subgroups may be a good example that will shed some light on understanding HRQOL and survivorship care of Asian-American sub-groups in a cultural context.

The Institute of Medicine recently presented guidelines for developing plans for follow-up care for cancer survivors (referred to as ‘survivorship care’) to improve their HRQOL [8]. However, a study reported that patients tend to be reluctant to actively seek survivorship care due to burdens dealing with unpleasant topics (i.e., recurrence, health maintenance) [9]. It suggests that patients’ confidence level in communicating with their healthcare providers (hereafter referred to as ‘self-efficacy in patient-physician communication ’) [10] can be an important trigger to facilitate optimal survivorship care for BCS, and ultimately improves HRQOL. Indeed, several studies demonstrated that self-efficacy in patient-physician communication predicted reduced distress [11, 12] and better HRQOL [13, 14]. One study found that Asian-Americans are less likely to be active in relationships with physicians, to ask questions, to receive medical information, and to talk about their concerns during doctor visits [15]. Cultural beliefs about physician among Asian-Americans (‘doctor is a powerful other’) may influence the lack of adequate communication with physicians [16].

Beyond the cultural context, communication between patients and physicians during the cancer treatment may be associated with decision support, which refers to supporting the patient in making decisions by providing clear information or emotional support, and sharing decision making [17]. It is reported that survivors who receive adequate medical information and support from health care providers tended to express their concerns and assert their preferences during medical appointments [18, 19]. Thus, decision support can facilitate patient-physician partnerships and communication to promote quality survivorship care in BCS, and in turn improve HRQOL [19, 20]. Several studies document that ethnic minority BCS tend to have less breast cancer knowledge and to receive less information than White survivors [21, 22]. For Chinese- and Korean-Americans, language barriers as well as cultural attitudes may impede obtaining the knowledge and information that can help to make a treatment decision [16].

As a comprehensive mechanism that can explain decision support, self-efficacy in patient-physician communication, and HRQOL, we also consider family communication because the family is viewed as a major source of support in Asian cultures [15]. Traditional Chinese and Korean cultures tend to uphold interdependent and collectivistic values to maintain interpersonal harmony, discouraging the expression of their emotional and physical distress to outside of family [23]. Given the limited social networks of immigrants [24], Asian-Americans who maintain their traditional cultural viewpoints may have higher expectations toward their family, emphasizing their quality family communication.

Several studies found that effective family communication is strongly related to more positive health outcomes, such as better psychological adjustment, HRQOL and effective treatment decision making [25, 26]. Another study reports that family members tend to assimilate the new information or situation and find a new sense of balance, based on quality family communication such as discussions or negotiations [27]. However, family communication relevant to decision making, information, such as that garnered from health care providers, and communication between patients and health care providers, have not been well integrated into the empirical research. An investigation of whether quality family communication translates into improved decision making and patient-family-physician communication may help patients to adapt throughout the course of the illness with better adherence to recommended treatment plans and greater satisfaction with survivorship care [28].

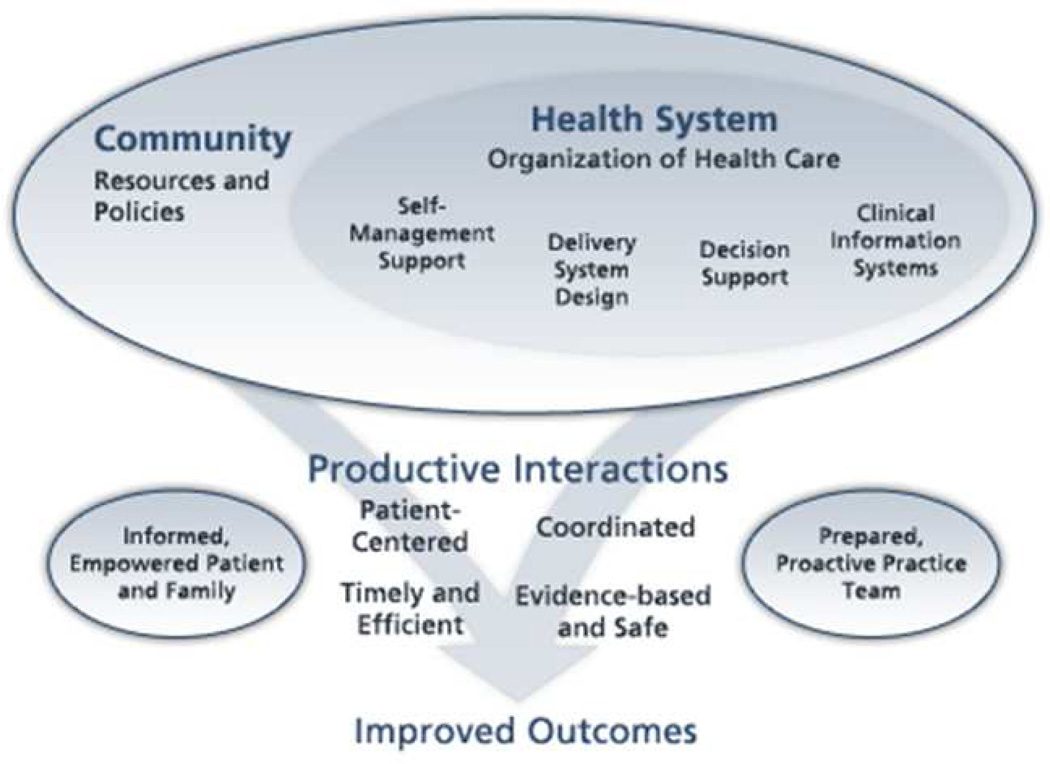

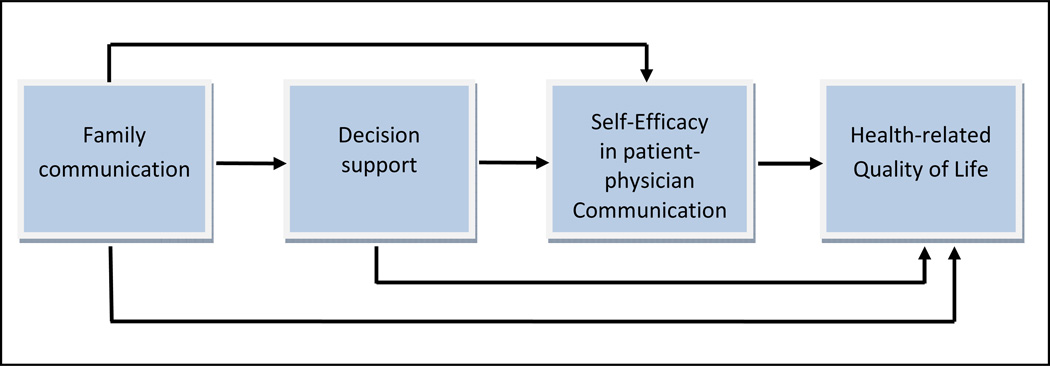

To investigate the relationship among family communication, decision support, selfefficacy in patient-physician communication, and HRQOL, the Chronic Care Model (Figure 1) was adapted to the theoretical model presented in this paper (Figure 2). The Chronic Care Model indicates that improvements in the support of self-management, decision support, clinical information systems, and the integration of community resources into health care systems will foster more productive interactions among patients and medical professionals and ultimately improve outcomes of chronic care [29]. Our theoretical model focuses on the relationships among decision support, patient-physician communication (interaction), and HRQOL. Additionally, family communication is added to reflect Asian cultures that emphasize familycentered values. Given that the Chinese group is generally more acculturated than the Korean group [6, 7], we assume that two groups may have different patterns in their relationships.

Figure 1. The Chronic Care Model.

Source: Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice. 1998;1(1):2–4.

Figure 2. Theoretical Model: Patient-Family-Healthcare Provider Communications influencing HRQOL.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study was (1) to compare family communication, decision support, self-efficacy in patient-physician communication, and HRQOL between Chinese- and Korean- American BCS; and (2) to investigate how family communication, decision support, and selfefficacy in patient-physician communication influence HRQOL among Chinese- and Korean- American BCS. We propose the following hypotheses:

H1: There will be differences in family communication, decision support, self-efficacy in patient-physician communication, and HRQOL between Chinese- and Korean-Americans.

H2: Self-efficacy in patient-physician communication will be directly and positively associated with HRQOL.

H3: Decision support will be directly and/or indirectly associated with HRQOL through selfefficacy in patient-physician communication.

H4: Family communication will be directly and/or indirectly associated with HRQOL through self-efficacy in patient-physician communication and/or decision support.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Participants were included if they 1) were within 1–5 years of breast cancer diagnosis (stages I-III); 2) had completed active treatment (surgery, radiation and/or chemotherapy); 3) had not been diagnosed with another type of cancer; 4) did not have any other major disabling medical (e.g., heart disease, stroke) or psychiatric condition (e.g., schizophrenia); 5) self- identified as Chinese- or Korean-American; and 6) were able to speak Mandarin/Cantonese, Korean, and/or English.

The participants were drawn from the California Cancer Surveillance Program (CSP) and area hospitals in Los Angeles [LA] County, US. Study participants were recruited as follows: (1) Investigators mailed invitation letters to BCS whose contact information was obtained from the CSP and local hospital registries; (2) A research assistant made telephone calls to follow-up on the invitation letter 2 weeks after the mailing; (3) If the potential participant was interested, a brief screening was conducted over the telephone to assess eligibility; (4) If they were eligible, a survey package including questionnaires and an informed consent form was mailed; and (5) If survivors had not returned the survey within 3 weeks, a research assistant made a reminder call. If they did not return the survey after the third follow-up reminder call, they were considered non-respondents. The Institutional Review Board approved all recruitment procedures.

In this study, 619 potential participants were mailed invitation letters. Of these, 369 were not accessible (no response to recruitment letter or to follow-up telephone call, or incorrect contact information), and 250 were accessible. Of the accessible potential participants, 157 BCS comprised the final sample, achieving a final response rate of 62.8% of the accessible sample. No significant difference in demographic and medical characteristics between respondents and non-respondents was found.

Instruments

The English-version standardized measures were first translated and then back-translated into Chinese or Korean by independent, bilingual translators using a rigorous “forward-backward” translation procedure. After completing the translations, the panel of translators compared the two English versions to make sure they were equivalent, and corrections were made until equivalence was achieved. Then, the questionnaire was pilot-tested with a small convenience sample, and revisions from the pilot-test were incorporated into the final questionnaires. Significant differences between the language versions did not exist.

Family communication

Family communication was assessed using the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales (FACES IV)–Family Communication Scale, which was designed to investigate the functionality of communication within the family [30]. In this measure, 10 items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating better family communication. A family communication score was computed by averaging all items. This measure showed good reliability, with a Crobach’s alpha of 0.96 for both groups.

Decision support

Decision support was adapted from the 10-item Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS). The DCS has been widely used to evaluate patients’ decisions regarding types of healthcare treatment [31]. The current study used 3 items in the DCS support subscale to assess decision support, which is defined as a feeling supported in making a choice or pressured to choose on course of action. Items include 1) I have enough support from others to make a choice, 2) I am choosing without pressure from others, and 3) I have enough advice to make a choice. In this study, participants were asked to think about moments that they had made health decisions, such as cancer treatment, in the past. For scoring decision support, items were reverse-coded and then averaged to obtain a mean score, indicating high scores reflected high decision support in heath decision. The reliability coefficients were 0.80 for Chinese- and 0.82 for Korean-Americans.

Self-efficacy in patient-physician communication

The self-efficacy in patient-physician communication was assessed using the Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interaction scale [32]. This scale uses 10 questions to assess a person’s confidence in her/his ability to communicate with her/his physician. The items are rated on 5-point Likert scale. For scoring, all items were reverse-coded and averaged into a mean score, with higher scores reflecting higher self-efficacy. The reliability coefficients were 0.96 for Chinese- and 0.95 for Korean-Americans.

Health-related quality of life

A 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) was used to assess HRQOL [33]. This measure generates 2 summary and 8 sub-scale scores. The 2 summary scores are the physical component summary (PCS; (1) physical functioning, (2) physical role limitation, (3) bodily pain, and (4) general health perception) and the mental component summary (MCS; (1) vitality, (2) social functioning, (3) emotional role limitation, and (4) mental health). Sub-scale scores were computed by summing items in each sub-scale and then transforming the raw scores to a range from 0 to 100. Higher scores on the summary and the 8 sub-scales indicate a better HRQOL. In this study, reliability coefficients for the SF-36 sub-scales ranged from 0.81 to 0.87 for Chinese- Americans and from 0.81 to 0.91 for Korean-Americans.

Demographic and medical characteristics

Self-reported demographic and medical characteristics, such as age, education, income, health insurance coverage, length of living in the US, cancer stage, years since diagnosis, and number of co-morbidities, were included and considered as control variables. The number of co-morbidities was obtained by summing the self-reported medical conditions from a list of 24 chronic medical conditions.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlation were conducted to elicit information on the main study variables. Independent sample t-tests and chi-squared tests were used to investigate whether demographic and medical variables are different between Chinese- and Korean- Americans. To compare differences in outcomes between the two ethnic groups (study aim 1), the univariate general linear model was used. Here, demographic and medical variables that showed significant differences between the two groups were included as control variables. The data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0. All hypotheses were tested using the p<0.05 criterion for significance.

Path analyses were conducted to investigate the overall effects of family communication, decision support, and self-efficacy in patient-physician communication on HRQOL using AMOS 20.0 (study aim 2). All of the missing data were imputed using the AMOS regression imputation maximum likelihood procedure [34]. As preliminary analyses, we first examined whether the four main variables differed by the participants’ demographic and medical characteristics using multiple linear regression. We found that the four main variables significantly differed by the number of co-morbidities, years since diagnosis, and income. Thus, in the following analyses, those variables were controlled to ensure that the estimates are above and beyond the linear effects of external elements [35].

Next, the relationship among variables were specified based on our theoretical model and the exploratory specification search procedure in AMOS to find the best fit model [36]. Thus, the hypothesized model was created by adding 1) the direct pathway of family communication, decision support, and self-efficacy in patient-physician communication on PCS and MCS; 2) a mediated-path structural model of decision support between family communication and self-efficacy in patient-physician communication, and of self-efficacy in patient-physician communication between decision support and PCS/MCS; 3) control variables influencing major variables (i.e., the number of co-morbidities, years since diagnosis, and income); and 4) covariances between PCS and MCS. The hypothesized model was evaluated for each ethnic group, using goodness of fit indies, including the chi-squared statistic or discrepancy function, the ratio of the discrepancy function to the degrees of freedom, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; acceptable fit ≤0.08) [37], and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; acceptable model fit ≥0.9) [38]. Additionally, Sobel’s test was used for verification of the mediation effects [39].

A comparison was then made between Chinese- and Korean-Americans using multiple group analysis. Initially, all parameters were allowed to be different between Chinese- and Korean-Americans (baseline model). Then, paths were constrained to test whether or not the model was equivalent in the paths between the two ethnic groups. The constrained model was compared against the baseline model by computing a chi-square different test. Here, a significant chi-square value at a p<0.05 is an indication that the path coefficients vary across the two groups.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Chinese- and Korean-American BCS were not significantly different by most demographic and medical characteristics (Table 1). However, education, cancer stage, surgery-axillary node dissection, and years since diagnosis showed significant differences between the two ethnic groups. Korean-Americans were more likely to have obtained higher levels of education. Chinese-Americans were more likely to have been diagnosed with breast cancer in stage II, whereas Korean-American BCS were more likely to have been diagnosed in stage I. The years since cancer diagnosis for Chinese-Americans were slightly less than that for Korean-Americans.

Table 1.

Demographic and Medical Characteristics

| Variables | Total (n=157) |

Chinese (n=86) |

Korean (n=71) |

X2/t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean; SD) | 55.3(9.7) | 55.2(9.7) | 53.9(9.7) | −0.19 |

| Length of stay in the US (mean; SD) | 23.9(11.7) | 23.5(12.2) | 23.9(9.9) | −0.48 |

| Education | ||||

| <High school | 18(11.5) | 16(18.6) | 2(2.8) | 10.05** |

| High school graduated | 25(15.9) | 11(12.8) | 14(19.7) | |

| >High school | 114(72.6) | 59(68.6) | 55(77.5) | |

| Household income | ||||

| <25K | 57(39.3) | 35(40.7) | 22(33.8) | 1.65 |

| 25K–45K | 25(17.2) | 13(15.1) | 12(18.5) | |

| 45K–75K | 26(17.9) | 14(16.3) | 12(18.5) | |

| >75K | 37(25.5) | 18(20.9) | 19(29.2) | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 125(79.6) | 69(80.2) | 56(78.9) | 0.04 |

| Others | 32(20.4) | 17(19.8) | 15(21.1) | |

| Health insurance | ||||

| Private | 65(46.8) | 38(48.7) | 27(45.0) | 1.17 |

| Public(Medicare/Medicaid) | 62(44.6) | 35(44.9) | 26(43.3) | |

| No insurance | 12(8.6) | 5(6.4) | 7(11.7) | |

| Primary language | ||||

| Own language(Chinese/Korean) | 142(90.4) | 76(88.4) | 66(93.0) | 0.95 |

| English | 15(9.6) | 10(11.6) | 5(7.0) | |

| Cancer stage | ||||

| 0 | 11(7.1) | 10(11.6) | 1(1.4) | 16.01** |

| I | 56(35.9) | 22(25.6) | 34(48.6) | |

| II | 68(43.6) | 45(52.3) | 23(32.9) | |

| III | 21(13.5) | 9(10.5) | 12(17.1) | |

| Surgery(Yes) | ||||

| Axillary node dissection | 61(38.9) | 39(45.3) | 22(31.0) | 3.38* |

| Lumpectomy | 82(52.2) | 45(52.3) | 37(52.1) | 0.00 |

| Mastectomy | 83(52.9) | 48(55.8) | 35(49.3) | 0.66 |

| Radiation(Yes) | 86(57.0) | 45(55.6) | 41(58.6) | 0.14 |

| Chemotherapy(yes) | 105(67.7) | 61(72.6) | 44(62.0) | 2.00 |

| Hormonal therapy(yes) | 99(63.9) | 58(68.2) | 41(58.6) | 1.55 |

| Years since diagnosis(Mean,SD) | 3.5(1.6) | 3.2(1.8) | 3.9(1.4) | −2.60* |

| Number of comorbidity(Mean,SD) | 3.5(3.3) | 3.8(3.2) | 3.0(3.4) | 1.48 |

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Differences in Predictor and Outcome Variables by Ethnicity

Family communication and self-efficacy in patient-physician communication did not differ between the two ethnic groups, after controlling for covariates (Table 2). However, decision support scores showed significant differences, indicating that Chinese-Americans are more likely than Korean-Americans to receive decisional support. In terms of HRQOL, PCS and MCS scores were not different between the two groups. Nevertheless, the physical functioning sub-scale differed significantly between Chinese- and Korean-Americans, with better scores in the Chinese-Americans.

Table 2.

Differences in Predictor and Outcome Variables by Ethnicity

| Variables | Chinese (n=86) | Korean (n=71) | Fa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(SD) | |||

| Family communication | 3.7(1.0) | 3.7(1.0) | 0.18 |

| Decision support | 3.9(0.6) | 3.6(0.7) | 6.20* |

| Self-Efficacy in Patient-physician communication | 3.8(0.9) | 3.8(0.8) | 0.17 |

| SF-36 | |||

| Physical Component Summary | 60.4(23.0) | 63.6(25.1) | 0.04 |

| Mental Component Summary | 63.5(22.4) | 67.2(23.5) | 0.27 |

| Physical functioning | 71.3(25.2) | 61.8(29.0) | 5.48* |

| Role-physical | 41.1(40.3) | 58.9(43.2) | 3.59 |

| Bodily pain | 70.7(23.8) | 75.1(24.8) | 0.35 |

| General health perception | 58.7(23.0) | 58.6(24.3) | 0.15 |

| Social functioning | 71.7(24.7) | 75.5(26.1) | 0.17 |

| Mental health | 69.2(19.5) | 69.0(19.8) | 0.02 |

| Role-emotional | 53.7(43.1) | 70.0(42.1) | 3.59 |

| Vitality | 58.5(20.2) | 54.2(20.6) | 2.05 |

Note.

Education, cancer stage, surgery-Axillary node dissection, and years since diagnosis have been controlled;

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

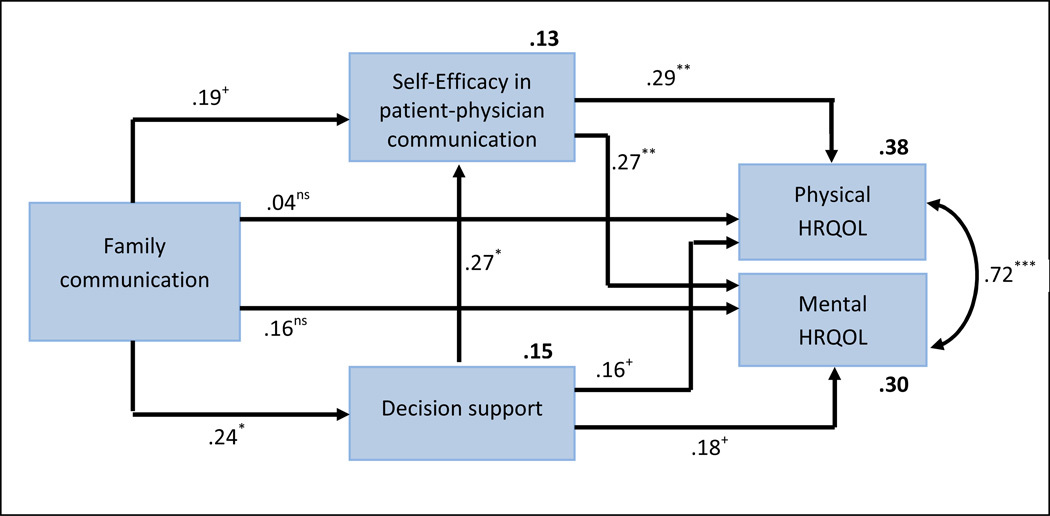

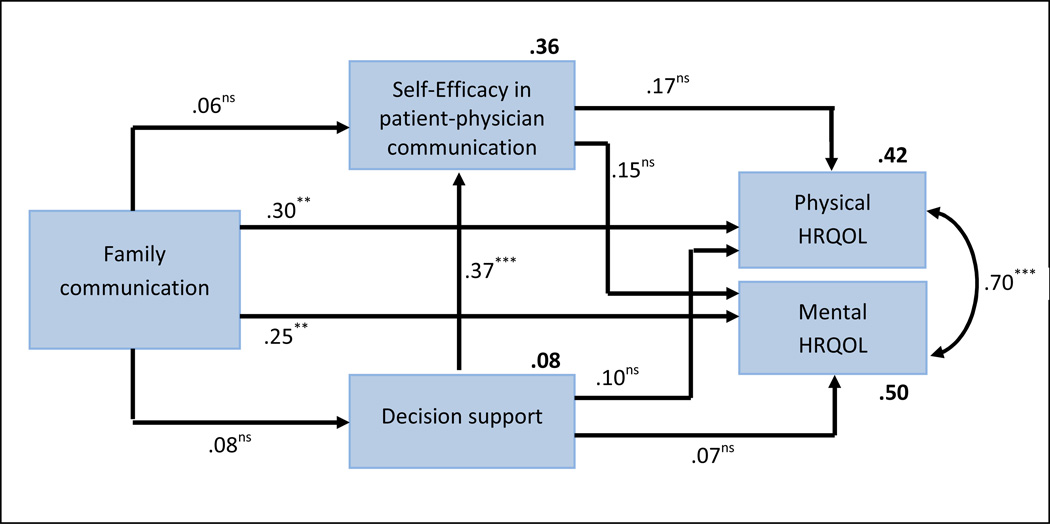

Path analysis of HRQOL

Based on the theoretical model and preliminary analysis, a path model was created that included two HRQOL outcomes (PCS and MCS), family communication, decision support, self-efficacy in patient-physician communication, and three covariates (co-morbidities, years since diagnosis, and income). This model produced excellent fit statistics for Chinese- and Korean- American BCS (Table 3). The model accounted for 38% of the variance in PCS and 30% in MCS for Chinese-Americans. For Korean-Americans, 42% and 50% of the variance in PCS and MCS was explained, respectively.

Table 3.

Fit Statistics for the Comparison Model

| Model | X2 | df | p | CFI | RMSEA |

Comparison |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔX2 | Δdf | p | ||||||

| Within-group | ||||||||

| Chinese | 11.26 | 8 | .188 | .98 | .07 | - | - | - |

| Korean | 3.86 | 8 | .869 | .99 | .01 | - | - | - |

| Between-group | ||||||||

| Unconstrained | 15.11 | 16 | .516 | .99 | .01 | |||

| Structural weights constrained | 45.74 | 34 | .086 | .96 | .05 | 30.63 | 18 | .032 |

Note. df= degree of freedom; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA = Root Mean Squared Residual.

As illustrated in Figures 3 and 4, self-efficacy in patient-physician communication was directly and positively associated with HRQOL for Chinese-Americans, whereas Korean- Americans did not show their significant relationships (H2). In our model, we did not demonstrate a direct relationship between decision support and HRQOL in either group (H3). However, an indirect relationship for decision support and HRQOL with self-efficacy in patient- physician communication was observed for Chinese-Americans only. Sobel statistics supported the indirect relationships between decision support and PCS only, through self-efficacy in patient-physician communication in Chinese-Americans (Sobel=1.93, p=0.027). That is, Chinese-American BCS who receive decision support show better self-efficacy in communication with their physician and, in turn, show higher physical HRQOL.

Figure 3. Results of the Path Analysis for Chinese-American BCS.

Note. The number of comorbidities, years since diagnosis, and income were included as control variables; Values shown are standardized regression coefficients. Direct effects are provided next to each arrow and explained variances are provided in bold above each variable; +p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns=not significant.

Figure 4. Results of the Path Analysis for Korean-American BCS.

Note. The number of comorbidities, years since diagnosis, and income were included as control variables; Values shown are standardized regression coefficients. Direct effects are provided next to each arrow and explained variances are provided in bold above each variable; *p < .05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns=not significant.

In terms of the relationship between family communication and HRQOL (H4), only Korean-Americans supported their direct relationships; but the indirect relationship of family communication on HRQOL was not observed. For Chinese-Americans, the indirect relationship between family communication and HRQOL through decision support and/or efficacy in patient-physician communication was observed. Sobel statistics supported the mediation role of decision support between family communication and self-efficacy in patient-physician communication (sobel=1.703, p=0.044). Thus, we demonstrated the indirect relationship of family communication on physical HRQOL through decision support and efficacy in patient-physician communication, in that order.

Multiple-Group Comparison

To examine whether the strengths of the structural paths were invariant across ethnic groups, a multiple group analysis was conducted with the hypothesized model. We compared a constrained model with a freely estimated model. The chi-square difference tests indicated a significant difference between these two models at a p<0.05 level (Table 3). It suggests that the strengths of these four structural paths varied between Chinese- and Korean-American BCS.

DISCUSSION

The current study compared family communication, decision support, self-efficacy in patient-physician communication, and HRQOL between Chinese- and Korean-American BCS, and investigated how family communication, decision support, and self-efficacy in patient-physician communication influenced HRQOL, based on the Chronic Care Model. In this study, we demonstrated that 1) only decision support variable, which indicates the extent of supporting people in making decisions, showed significant differences between Chinese- and Korean- American BCS; 2) self-efficacy in patient-physician communication variable (i.e., patients’ confidence in communicating with health care providers) was directly and positively associated with HRQOL for Chinese-Americans only; 3) decision support was indirectly associated with HRQOL through self-efficacy in patient-physician communication for Chinese-Americans only; 4) family communication was directly related to HRQOL for Korean-Americans, while Chinese- Americans showed their indirect relationship through decision support and/or self-efficacy in patient-physician communication; and 5) the multiple group analysis demonstrated that the structural paths varied across the two ethnic groups. Thus, our hypotheses were partially confirmed in this study.

Communication in survivorship care for BCS is an integral and complex process that involves multi-level interactions, understanding the content of the discussion, considers the relational aspects of cultures among patients, family, and healthcare providers, and ultimately influence HRQOL [40–42]. However, it is largely understudied in ethnic minority BCS. To our knowledge, this study is the first investigation examining the relationships among family communication, decision support, self-efficacy in patient-physician communication, and HRQOL in Chinese- and Korean-American BCS. Our study may be one example to test whether the “communication” component in the Chronic Care Model is appropriate to explain survivorship care in Asian culture, although the model was not fully applied to this study.

Our study findings showed significant differences in the overall model between Chinese-and Korean-American BCS, as demonstrated in results from the multiple group analysis. First, for Chinese-Americans, self-efficacy in patient-physician communication was directly and positively associated with HRQOL, consistent with other studies [11, 14]. Patients’ self-efficacy and confidence in communicating with physicians may be an essential factor which represents patient-centered communication including an exploration of illness and symptoms, a mutual definition of the issue, and the establishment of treatment goals. Hence, our findings suggest that holding strong self-efficacy in patient-physician communication is necessary to improve the HRQOL for Chinese-American BCS. However, it is known that Asian-Americans including Chinese-Americans tend to unconditionally follow physicians’ recommendations, thinking of them as a ‘powerful other’ [16]. Our possible explanation is that communication and relationship between patient and physician may vary depending upon the level of acculturation. Our preliminary analyses showed that Chinese-Americans are more likely than Korean-Americans to be acculturated (F=18.67, p<0.001). Thus, acculturated Chinese-American BCS may recognize the importance of patient-centered communication which may influence improving their HRQOL.

Meanwhile, unlike Chinese-Americans, a positive and direct relationship between family communication and HRQOL was observed for Korean-American BCS. Given that Korean- Americans are less likely than Chinese-Americans to be acculturated, Korean-Americans may hold traditional cultural viewpoints, establishing reciprocal relationships among own family members rather than other healthcare providers. It may also add the importance of quality family communication during the survivorship stage. Thus, the ability of Korean-American BCS to effectively communicate to manage general concerns within the family may provide the strength needed to solve family conflicts and ultimately improve HRQOL.

It is often reported that a good decision support system can result in a better quality of cancer care, increased satisfaction, and improved self-esteem for patients [43]. In this study, we hypothesized that there is a direct relationship between decision support and HRQOL; this hypothesis was not supported in our sample. Rather, we found their indirect relationship through self-efficacy in patient-physician communication. According to the Chronic Care Model, effective chronic-illness management programs require that providers have the knowledge required for optimal patient care to help survivors make decisions more effectively. Survivors also need the confidence and skills to obtain what they need from the health care system to achieve productive interaction between survivors and physicians [29, 44]. Therefore, our study finding which shows a positive relationship between decision support and self-efficacy in patient-physician communication for both Chinese- and Korean-American BCS seems to support the Chronic Care Model.

Furthermore, we demonstrated the mediating role of decision support between family communication and self-efficacy in patient-physician communication in the Chinese group only. In fact, we assumed that decision support might be a core component that links the relationship between family and healthcare providers in terms of communication in survivorship care. Although it is still debatable as to what extent family members can be involved in a patient’s decision-making process, some studies report that a spouse’s presence is important for patients to obtain information and make decisions [42, 45]. In this study, cultural context may play an important role in whether, and to what extent, survivors discuss treatment decisions with their family. Indeed, in each ethnic model, Chinese-Americans’ family communication was significantly associated with decision support, whereas Korean-Americans did not support such relationship. It implies that Chinese and Korean cultures per se may have different communication and decision-making styles because language and communication systems are a part of culture [46]. Although diversity within languages and different acculturation level exists between the two ethnic groups, future studies are warranted to further investigate the dynamic process between family communication and decision support for BCS.

The multiple group analysis confirmed significant differences in the overall model between Chinese- and Korean-American BCS. It suggests that socio-cultural differences between two ethnic subgroups might influence how communication components among survivors, family, and healthcare providers are associated with HRQOL. Hence, our study provides evidence that supports disaggregated approaches to Asian-American subgroups, considering their cultural contexts. Although the current study did not include culture related variables beyond ethnicity, we argue that ethnicity in itself may imply shared culture and traditions that are distinctive, maintained between generations, and lead to a sense of identity [46], given that ethnicity is another way of thinking about human diversity [47]. The current study also provides practical information on how to improve HRQOL for Chinese- and Korean-American BCS based on communication interventions. For example, an approach to improve self-efficacy in communicating between patients and physicians with providing decision support may be effective in improving HRQOL for Chinese-Americans. For Korean-Americans, encouraging effective communicate within the family may positively influence HRQOL.

This study has several limitations. First, our data was collected by participants’ self-report. Specifically, participants were asked to recall the decision support during the cancer treatment period; these findings may be influenced by recall biases. Second, findings may not be generalizable to all Chinese- or Korean-American populations due to small sample sizes. The study participants were also from the mainly LA County. Cultures of the LA County may vary from those in other parts of the country. Third, the proposed model is cross-sectional and causality cannot be assumed. Although we used retrospective data to assess decision support, the results need to be interpreted with caution; a longitudinal study will be necessary to fully understand the relationship among variables. Finally, the Chronic Care Model was not fully applied to the current study; thus other factors within the model may influence our results.

Overall, our results provide insight into communication components in survivorship care to improve HRQOL of Chinese- and Korean-American BCS. Effective communication in survivorship care can be of benefit to survivors, encouraging understanding about medical information, reducing distress about symptoms, and minimizing distortions of information. For family, involvement in decision support and good family communication can promote family well-being and quality of life with a stabilization of concerns, and support the transition into the patients’ survivorship care. For healthcare providers, effective communication can provide risk management for the patient and family, help the patient and family process information, and reduce iatrogenic errors and burnout [28]. Thus, communication skills to manage conflict and attain consensus among survivors, family, and healthcare providers are essential to improve HRQOL for BCS. Additionally, the cultural contexts should be considered to determine ethnically and culturally tailored communication approach.

Acknowledgements

This work funded through National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (R03CA139941). Also, authors wish to express gratitude for the support and assistance received from the following mentors, consultants, and assistants: Kimlin Ashing-Giwa, Kathleen Ell, Joseph Kim, Anjela Jo, Sophia Yeung, and Okmi Baik.

Abbreviations

- BCS

Breast Cancer Survivors

- CFI

The Comparative Fit Index

- CSP

Cancer Surveillance Program

- DCS

Decisional Conflict Scale

- FACES

Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales

- HRQOL

Health-Related Quality of Life

- MCS

Mental Component Summary

- PCS

Physical Component Summary

- RMSEA

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

- SF-36

A 36-item Short-Form Health Survey

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests:

None of the sponsors played any role in the study design, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit it for publication. We have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review our data if requested.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau. 2010 American Community Survey. Book 2010 American Community Survey, City; 2011. In: Editor (ed)^(eds) [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Book Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2011–2012. American Cancer Society, City; 2011. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2011–2012. In: Editor (ed)^(eds) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srinivasan S, Guillermo T. Toward improved health: disaggregating Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander data. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1731–1734. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mui AC, Shibusawa T. Asian American elders in the twenty-first century: Key indicators of well-being. New York: Columbia University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uba L. Asian Americans: Personality, patterns, identity, and mental health. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nee V, Wong HY. Asian American socioeconomic achievement: the strength of the family bond. Sociological Perspectives. 1985;28:281–306. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishii-Kuntz M. Intergenerational relationships among Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. Americans Family Relations. 1997;46:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine. Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, Cook EF, Earle CC. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2489–2495. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New Yrok: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vivar CG, McQueen A. Informational and emotional needs of long-term survivors of breast cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51:520–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teutsch C. Patient-doctor communication. Med Clin North Am. 2003;87:1115–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(03)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maliski SL, Kwan L, Krupski T, Fink A, Orecklin JR, Litwin MS. Confidence in the ability to communicate with physicians among low-income patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2004;64:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maly RC, Stein JA, Umezawa Y, Leake B, Anglin MD. Racial/ethnic differences in breast cancer outcomes among older patients: effects of physician communication and patient empowerment. Health Psychol. 2008;27:728–736. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kagawa-Singer M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psychooncology. 2003;12:38–58. doi: 10.1002/pon.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim J-W, Gonzalez P, Wang M, Ashing-Giwa KT. Understanding the cultural health belief model influencing health behaviors and health-related quality of life between Latina and Asian-American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1137–1147. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasricha A, Deinstadt RT, Moher D, Killoran A, Rourke SB, Kendall CE. Chronic care model decision support and clinical information systems interventions for people living with HIV: A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2145-y. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon HS, Street RL, Sharf BF, Souchek J. Racial differences in doctor's information-giving and patients' participation. Cancer. 2006;107:1313–1320. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Royak-Schaler R, Passmore SR, Gadalla S, Hoy MK, Zhan M, Tkaczuk K, Harper LM, Nicholson PD, Hutchison AP. Exploring patient-physician communication in breast cancer care for African American women following primary treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:836–843. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.836-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doubeni CA, Field TS, Yood MU, Rolnick SJ, Quessenberry CP, Fouayzi H. Patterns and predictors of mammography utilization among breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2006;106:2482–2488. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paskett eD, Tatum C, Rushing J, Michielutte R, Bell RA, Foley KL. Racial differences in knowledge, attitudes, and cancer screening practices among a triracial rural population. Cancer. 2004;101:2650–2659. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maly RC, Leake B, Silliman RA. Health care disparities in older patients with breast carcinoma: Informational support from physicians. Cancer. 2003;97:1517–1527. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeh CJ, Inman AG, Kim AB, Okubo Y. Asian American families' collectivistic coping strategies in response to 9/11 Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12:134–148. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim J-W, Zebrack B. Different pathways in social support and quality of life between Korean American and Korean Breast and Gynecological Cancer Survivors Qual Life Res. 2008;17:679–689. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang AY, Siminoff LA. Silence and cancer: why do families and patients fail to communicate? Health Communication. 2003;15:415–429. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1504_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping and its significant for marital functioning. In: Revenson T, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples coping with stress: emerging perspectives on dyadic coping. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clayman ML, Galvin KM, Arntson P. Shared decision making: fertility and pediatric cancers. In: Woodruff TK, Snyder KA, editors. Oncofertility. New York: Springer; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powazki RD. The family conference in oncology: benefits for the patient, family, and physician. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011;38:407–412. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olson DH, Gorall DM, Tiesel JW. FACES IV Package. Minneapolis, MN: Life Innovations; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Connor AM. Validation of a Decisional Conflict Scale Med Decis Making. 1995;15:25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maly R, Marshal G, DiMatteo M. Perceived efficacy in patient-physician interaction (PEPPI): validation of an instrument in older persons. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 1998;46:889–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston: Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blunch N. Introduction to structural equation modeling using SPSS and AMOS. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schumacker RE. Conducting specification searches with Amos Structural Equation Modeling. 2006;13:118–129. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bentler PM. Comparative fix indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological Methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brundage M, Feldman-Stewart D, Tishelman C. How do interventions designed to improve provider-patient communication work? Illustrative applications of a framework for communication. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:136–143. doi: 10.3109/02841860903483684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Cannadian Medical Association Journal. 1995;152:1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rim SH, Hall IJ, Fairweather ME, Fedorenko CR, Ekwueme DU, Smith JL, Thompson IM, Keane TE, Penson DF, Moinpour CM, Zeliadt SB, Ramsey SD. Considering racial and ethnic preferences in communication and interactions among the patient, family member, and physician following diagnosis of localized prostate cancer: study of a US population. Internal Journal General Medicine. 2011;4:481–486. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S19609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards A, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making in health care" achieving evidence-based patient choice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glasgow RE, Orleans CT, Wagner EH. Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? The Milbank Quarterly. 2001;79:579–612. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davision BJ, Gleave ME, Goldenberg SL, Degner LF, Hoffart D, Berkowitz J. Assessing information and decision preferences of men with prostate cancer and their partners. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25:42–49. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200202000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim JW. The role of culture and ethnicity in the adjustment to gyneccological cancer. Current Women's Health Reviews. 2011;7:379–390. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dein S. Race, culture and ethnicity in minority research: a critical discussion. J Cult Divers. 2006;13:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]