Abstract

A regiospecific synthesis of multi-functional pyrazoles has been developed from a cascade process triggered by Rh(II)-catalyzed dinitrogen extrusion from enoldiazoacetates with vinylogous nucleophilic addition followed by Lewis acid catalyzed cyclization and aromatization.

INTRODUCTION

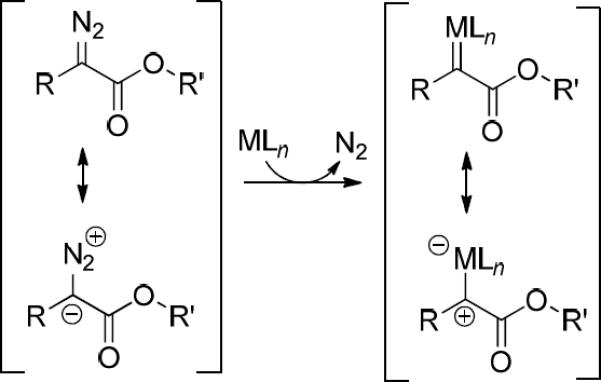

Diazo compounds have been extensively studied during the last few decades, and their value in organic synthesis is well known.1, 2 Direct dipolar cycloaddition to α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds and nitriles3 as well as catalytic processes have provided effective methodologies for the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds.4 Catalytic generation of metal carbenes for heterocyclic syntheses have been performed with diazocarbonyl compounds ranging from diazoacetates4e, 4g and diazomalonates3e to diazo ketones4a, 4f and diazoacetoacetates4d, although vinyldiazoacetates have also been employed.1a A key element in the uses of these diazo compounds is the change of polarity in the carbon alpha to the carbonyl group in the catalytic transformation to an electrophilic metal carbene (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Change in polarity from diazocarbonyl compounds to the correspong metal carbenes

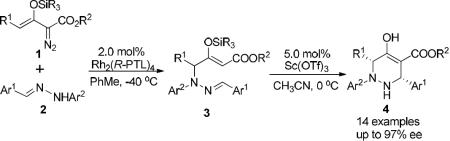

Increased attention has recently been given to enoldiazoacetates where the generated metal enolcarbene shows electrophilic character at both the carbene and vinylogous positions, and preferential reaction occurs at the vinylogous position.5,6 In one example of a vinylogous reaction we reported a stepwise [3+3]-cycloaddition of enoldiazoacetates 1 with diarylhydrazones 2 in which Rh2(R-PTL)4 catalyzed highly enantioselective vinylogous N-H insertion; subsequent Sc(OTf)3-catalyzed Mannich addition generated the corresponding tetrahydropyridazine derivatives 3 in high yield and diastereoselectivity (eq 1).7 Shortly thereafter Vicario8 and Lassaletta9 independently reported using donor-acceptor substituted hydrazones as acyl anion equivalents that undergo addition reactions with α,β-unsaturated aldehydes or ketoesters, respectively, at the hydrazone carbon instead of at the conjugated hydrazone nitrogen. These successful examples of umpolung transformations suggested that reactions of metal enolcarbenes with donor-acceptor disubstituted hydrazones could have a different outcome than was found with 2 in eq 1, forming 6 or 7 instead of 3 in dirhodium(II) catalyzed reactions (Scheme 2). This transformation and the subsequent outcome from Lewis acid catalysis have been explored.

|

(1) |

Scheme 2.

Umpolung with donor-acceptor substituted hydrazones in dirhodium(II) catalyzed reactions of 1

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

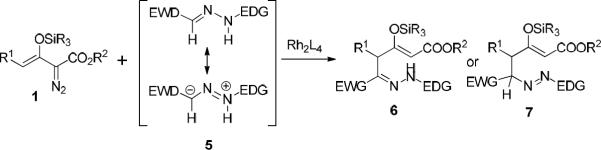

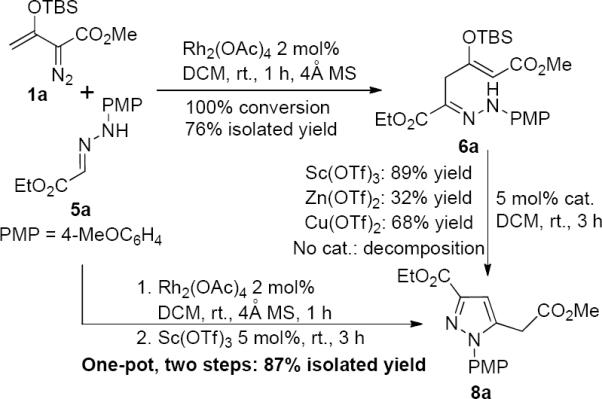

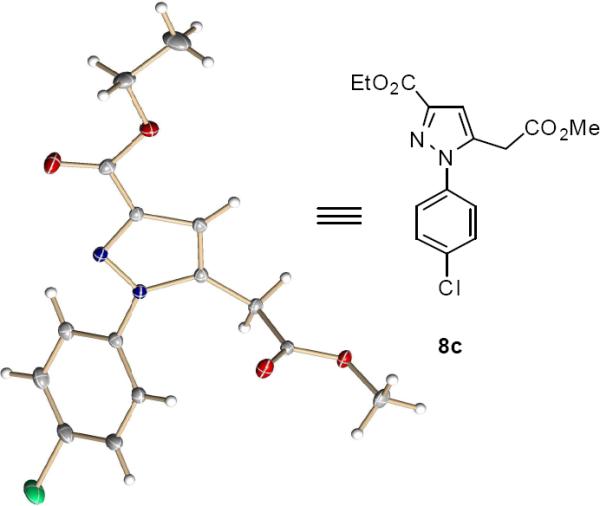

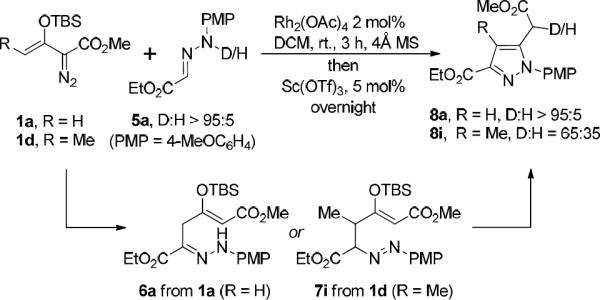

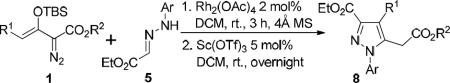

At the onset we enlisted methyl enoldiazoacetate 1a and donor-acceptor substituted hydrazone 5a as substrates, and their rhodium acetate catalyzed reaction rapidly underwent complete conversion to give 6a in 76% isolated yield.10 Although 6a was unstable and decomposed slowly in dichloromethane, this product was converted to pyrazole 8a efficiently when catalyzed by a Lewis acid, and Sc(OTf)3 offered the best results with 89% isolated yield (Scheme 3). The structure of the pyrazole product 8 was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of its chloro-derivative 8c (Figure 1).11 To increase reaction efficiency we carried out the two-step process in one-pot since both of the two reactions are carried out in dichloromethane. By adding Sc(OTf)3 directly into the reaction mixture at room temperature immediately after complete conversion to 6a, pyrazole product 8a was smoothly generated in high yield (87% isolated yield from 5a) which avoided unnecessary losses from isolation of intermediate 6.

Scheme 3.

Two-step conversion compared to one-pot two-step process

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of 8c

The pyrazole scaffold is well-represented in bioactive structures.12 Pyrazoles having functionality installed at the C-3 or C-5 position have attracted a significant amount of attention.13 Numerous methodologies have been reported for pyrazole syntheses,14 and the Knorr condensation reaction of dicarbonyl compounds is the most prevalent approach for pyrazole synthesis.15 However, this classic condensation between α,γ-diketoesters and hydrazines is hampered by low regioselectivity16 and general synthetic processes for functionalized pyrazoles having structural diversity and complexity continue to be needed. With the process that is described in Scheme 3 we present a versatile cascade reaction to produce multi-functionalized pyrazoles by a dirhodium(II)-catalyzed vinylogous umpolung reaction followed by Lewis acid catalyzed cyclization and aromatization.

To test the generality of this cascade reaction, a series of donor-acceptor substituted hydrazones was employed under the same conditions. In all cases, the isolated yield of the pyrazoles exceeded 70%, regardless of the electronic properties and different substituents at the aryl group (entries 1~6). In addition, changing the ester alkyl group of the enoldiazoacetate (R2) from methyl to tert-butyl and benzyl gave the same product yields (entries 1, 7 and 8), but substituents other than hydrogen at the vinylogous position (R1) lowered product yield by about 10% in going from hydrogen to methyl and an additional 20% by changing from methyl to ethyl (entries 9, 11, and 12). Reactions with more sterically bulky substrates (e.g., enoldiazoacetate with R1 = Ph or the donor-acceptor substituted hydrazone derived from ethyl 2-oxopropanoate) showed only decomposition of the diazo compound.

The proton transfer step of the hydrazone carbon-centered vinylogous addition was further studied by using deuterium-labeled hydrazone 5a in reactions with enodiazoacetate 1a. Deuterium was found to reside exclusively on the carbon alpha to the carboxylate ester in the pyrazole product 8a formed between 1a and 5a. However, with vinyl-substituted enoldiazoacetate 1d (R1 = Me) in this reaction, only 65% of the deuterium was found in the final pyrazole product 8i (Scheme 4). These diverse results prompted us to look at the intermediates of the vinylogous addition step (6a and 7i), and 2D-SHQC NMR analysis showed that these two isolated compounds possessed different structures: 6a had a C-N double bond while 7i had a N-N double bond.17

Scheme 4.

Labeling experiments define outcome of vinylogous addition step

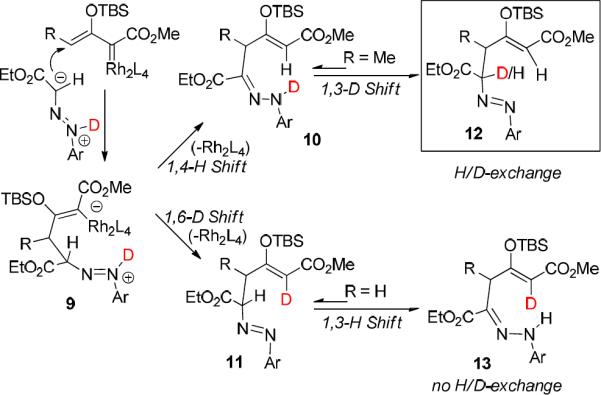

The loss of deuterium in forming pyrrazole product 8i was rationalized as due to proton shifts in reaction intermediates as shown in Scheme 5, although alternative hydrazone N-H insertion at the metal carbene center followed by an aza-[3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement cannot be ruled out. Kinetically controlled 1,4-H and 1,6-D shifts of the vinylogous addition intermediate 9,18 dependent on the acidity of the proton adjacent to the carboxylate group, give 10 and 11, respectively, and 10 is prone to deuteron-proton exchange (from 10 to 12) with further loss occurring during cyclization and aromatization.

Scheme 5.

Possible pathways for deuterium retention/loss

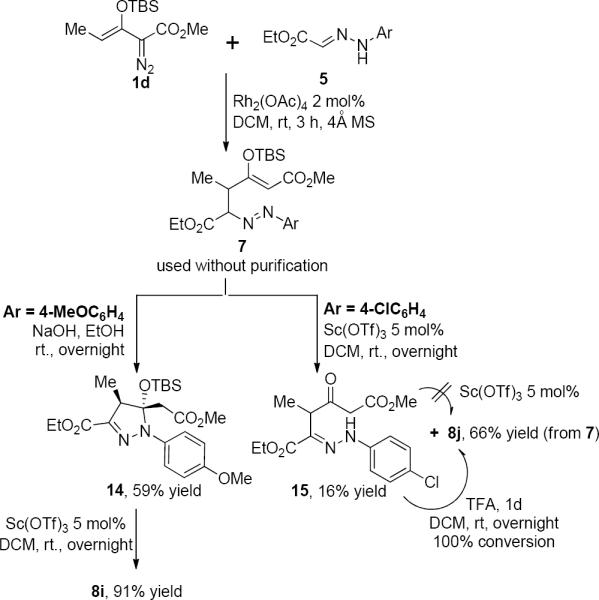

Further investigation of the cyclization step using base instead of Lewis acid with the reaction mixture from 1d and 5 that contained azo compound 7 demonstrated that the enolcarbene-generated vinylogous addition product can be converted to the ring-closed product through catalysis by sodium hydroxide in ethanol at room temperature. The cyclized pyrazole precursor 14 was formed in 59% isolated yield as only one diastereoisomer (Scheme 6)19 and was smoothly converted to pyrazole 8i in high yield under the same conditions as was reported with Sc(OTf)3 in Table 1. The base-promoted reaction is consistent with a mechanism through which the hydrazone anion undergoes intramolecular Michael addition, and this pathway differs from that of the conventional pyrazole synthsis via the Knorr condensation reaction in which a hydrazine anion directly attacks the carbonyl carbon.20 Support for this proposal - that of Michael addition instead of attack on the carbonyl group formed by hydrolysis of the vinyl silyl ether - comes from a reaction of a hydazone derivative 15 that was formed as a byproduct from the Sc(OTf)3-catalyzed reaction of 7; compound 15 has the same structural framework as the intermediate of the Knorr reaction.16d This byproduct (15) did not form the pyrazole product under standard Lewis acid conditions with Sc(OTf)3 (Table 1) even after treatment for 24 hours, and only with trifluoroacetic acid did conversion to 8j occur.

Scheme 6.

Table 1.

Substrate generality in the one-pot production the pyrazoles

| entry | R1/R2 (1) | Ar in 5 | 8 | yield 8(%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H/Me (1a) | 4-MeOC6H4 (5a) | 8a | 87 |

| 2 | H/Me (1a) | 4-MeC6H4 (5b) | 8b | 91 |

| 3 | H/Me (1a) | 4-ClC6H4 (5c) | 8c | 90 |

| 4 | H/Me (1a) | Ph (5d) | 8d | 89 |

| 5 | H/Me (1a) | 4-NO2C6H4 (5e) | 8e | 71 |

| 6 | H/Me (1a) | 2,4-2ClC6H3 (5f) | 8f | 72 |

| 7 | H/t-Bu (1b) | 4-MeOC6H4 (5a) | 8g | 89 |

| 8 | H/Bn (1c) | 4-MeOC6H4 (5a) | 8h | 88 |

| 9 | Me/Me (1d) | 4-MeOC6H4 (5a) | 8i | 74 |

| 10 | Me/Me (1d) | 4-ClC6H4 (5c) | 8j | 66 |

| 11 | Me/Bn (1e) | 4-MeOC6H4 (5a) | 8k | 69 |

| 12 | Et/Bn (1f) | 4-MeOC6H4 (5a) | 81 | 48 |

Reactions were carried out on a 0.5 mmol scale: 1 (0.6 mmol), 5 (0.5 mmol), 4 Å MS (100 mg), in 3.0 mL DCM with Rh2(OAc)4 (2.0 mol%) at room temperature; then Sc(OTf)3 (5.0 mol%) was added and stirred at room temperature overnight.

Isolated yield of 8 based on limiting reagent 5.

In conclusion, we have developed a regiospecific cascade transformation that enables the efficient preparation of multi-functional pyrazoles starting from enoldiazoacetates and donor-acceptor substituted hydrazones in good to high overall yields. The sequence of reactions is triggered by Rh(II)-catalyzed dinitrogen extrusion from enoldiazoacetates to form the substrate-dependent intermediates with C-N (6) or N-N (7) double bond followed by Lewis acid promoted direct addition and aromatization. Although many nucleophilic addition reactions to vinylogous position have been reported, this is the rare example using the hydrazone's “C” instead of “N” for vinylogous reactivity. Further expansions of vinylogous reactions with enoldiazoacetates are being pursued.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Information

Reactions were performed in oven-dried (140 °C) glassware under an atmosphere of dry N2. Dichloromethane (DCM) was passed through a solvent column prior to use and was kept over 3 Å molecular sieves. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out using silica gel plates. The developed chromatogram was analyzed by a UV lamp (254 nm). Liquid chromatography was performed using flash chromatography of the indicated system on silica gel (230–400 mesh). 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 on a 400 MHz spectrometer; chemical shifts are reported in ppm with the solvent signals as reference, and coupling constants (J) are given in Hertz. The peak information is described as: br = broad, s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, and comp = composite. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were performed on a TOF-CS mass spectrometer using CsI as the standard. Dirhodium tetraacetate, scandium(III) triflate and other Lewis acids were obtained commercially and used as received. Enoldiazoacetates 121 were synthesized according to literature procedures. Hydrazones 5 were synthesized as described.8

General Procedure for the Preparation of Hydrazones 5

A suspension of aryl hydrazine hydrochloride (14.0 mmol) in anhydrous THF (20.0 mL) was treated with triethylamine (2.0 mL, 14.0 mmol) before a solution of ethyl glyoxylate (50 % solution in toluene, 2.9 mL, 14.5 mmol) was added dropwise into the reaction mixture at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at this temperature for 30 minutes and then for 12 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture was then filtered under vacuum to collect the triethylamine hydrochloride salt. The filtrates were concentrated under reduced pressure, and the resulting solid was dissolved in dichloromethane (30 mL) then washed with HCl 1M (20 mL) and water (2 × 20 mL). The resulting organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure to produce the desired hydrazone 5 that was further purified by recrystallization from ether before use.

General Procedure for the Dirhodium-Catalyzed Reactions

To an oven-dried flask containing a magnetic stirring bar, 4 Å molecular sieves (100 mg), Rh2(OAc)4 (2.0 mol %) and hydrazone 5 (0.50 mmol) in dichloromethane (2.0 mL), was added enoldiazoacetate 1 (0.60 mmol) in dichloromethane (1.0 mL) over 1 h via a syringe pump at 0 °C. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (eluent: hexanes:EtOAc = 50:1 to 30:1) to give the pure product 6 or 7.

(2Z,5E)-6-Ethyl 1-Methyl 3-[(tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)oxy]-5-(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)hydrazono)hex-2-enedioate (6a)

Yellow oil. 100% conversion, 170 mg (0.38 mmol), 76% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 8.18 (bs, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.85 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 5.03 (s, 1H), 4.31 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.60 (s, 3H), 3.49 (s, 2H), 1.38 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.01 (s, 9H), 0.31 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 165.5, 165.0, 160.5, 155.6, 136.9, 128.6, 115.7, 114.8, 99.1, 61.5, 55.7, 50.8, 33.9, 25.9, 18.7, 14.5,−3.9; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C22H35N2O6Si [M+H]+: 451.2259; found: 451.2231.

(Z)-6-Ethyl 1-Methyl 3-[(tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)oxy]-5-[(E)-(4-methoxyphenyl)diazenyl]-4-methylhex-2-enedioate (7i)

Yellow oil. 100% conversion, 193 mg (0.42 mmol), 83% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.74 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 5.12 (s, 1H), 5.52 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 4.62–4.21 (comp, 2H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.63 (s, 3H), 3.34–3.27 (m, 1H), 1.29–1.26 (comp, 6H), 1.03 (s, 9H), 0.31 (s, 3H), 0.29 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 169.6, 168.0, 165.9, 162.4, 146.3, 124.9, 114.2, 98.9, 81.3, 61.6, 55.8, 50.8, 44.0, 26.2, 18.9, 15.4, 14.4, −3.6, −3.7; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C23H37N2O6Si [M+H]+: 465.2415; found: 465.2443.

General Procedure for the Lewis Acid Catalyzed Pyrazole Synthesis (Method A)

To an oven-dried flask containing a magnetic stirring bar, Lewis acid (5.0 mol %) and 6 or 7 (0.30 mmol) in dichloromethane (2.0 mL) were stirred for 3 h (or as indicated) at room temperature. Once the diazo compound was consumed [determined by TLC, eluent: hexanes:EtOAc = 2:1, Rf (material) ≈ 0.8, Rf (product) ≈ 0.1], the reaction mixture was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (eluent: hexanes:EtOAc = 3:1 to 1:1) to give the pure pyrazole 8 in high yield.

General Procedure for Pyrazole Synthesis in One-pot (Method B, Table 1)

To an oven-dried flask containing a magnetic stirring bar, 4 Å molecular sieves (100 mg), Rh2(OAc)4 (2.0 mol %) and hydrazone 5 (0.50 mmol) in dichloromethane (2.0 mL), was added enoldiazoacetate 1 (0.60 mmol) in dichloromethane (1.0 mL) over 1 h via a syringe pump at 0 °C. The reaction solution was stirred for another 2 h at room temperature followed by adding solid Sc(OTf)3 (5.0 mol %) directly into the reaction mixture and was stirred overnight under the same conditions. The crude reaction mixture was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (eluent: hexanes:EtOAc = 3:1 to 1:1) to give the pure pyrazole 8 in good to high yield.

Ethyl 5-(2-Methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8a)

Yellow oil. 138 mg (0.44 mmol), 87% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.33 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.90 (s, 1H), 4.40 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.66–3.65 (comp, 5H), 1.38 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 169.3, 162.4, 160.2, 144.0, 137.5, 131.6, 127.6, 114.4, 109.9, 61.1, 55.7, 52.6, 32.0, 14.5; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C16H19N2O5 [M+H]+: 319.1288; found: 319.1278.

Ethyl 5-(2-Methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-1-(p-tolyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8b)

Yellow oil. 137 mg (0.46 mmol), 91% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.30 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.91 (s, 1H), 4.40 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.68 (s, 2H), 3.65 (s, 3H), 2.40 (s, 3H), 1.38 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 169.3, 162.4, 144.1, 139.4, 137.4, 136.2, 129.9, 126.0, 110.1, 61.1, 52.6, 32.0, 21.3, 14.5; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C16H19N2O4 [M+H]+: 303.1339; found: 303.1348.

Ethyl 1-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8c)

White solid, mp = 109–110 °C. 145 mg (0.45 mmol), 90% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.44 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.90 (s, 1H), 4.38 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.68 (s, 2H), 3.65 (s, 3H), 1.37 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 169.1, 162.2, 144.5, 137.4, 137.2, 135.2, 129.6, 127.3, 110.5, 61.2, 52.6, 31.9, 14.4; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C15H16ClN2O4 [M+H]+ 15H16ClN2O4 [M+H]+: 323.0793; found: 323.0799.

Ethyl 5-(2-Methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8d)

Yellow oil. 128 mg (0.45 mmol), 89% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.48–7.42 (comp, 5H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 4.41 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.70 (s, 2H), 3.65 (s, 3H), 1.39 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 169.2, 162.4, 144.3, 138.7, 137.4, 129.4, 129.3, 126.1, 110.2, 61.2, 52.6, 32.0, 14.5; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C15H17N2O4 [M+H]+: 289.1183; found: 289.1172.

Ethyl 5-(2-Methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8e)

Yellow solid, mp = 124–126 °C. 118 mg (0.36 mmol), 71% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 8.39 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 7.75 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (s, 1H), 4.45 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.81 (s, 2H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 1.42 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 169.0, 162.0, 147.7, 145.6, 134.8, 137.6, 126.4, 125.0, 111.7, 61.6, 53.0, 32.2, 14.6; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C15H16N3O6 [M+H]+: 334.1034; found: 334.1031.

Ethyl 1-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-5-(2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8f)

White solid, mp = 81–82 °C. 128 mg (0.36 mmol), 72% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.54 (s, 1H), 7.43–7.37 (m, 2H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 4.40 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.70–3.44 (comp, 5H), 1.38 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 168.7, 162.1, 145.2, 138.8, 136.9, 134.9, 133.3, 131.2, 130.2, 128.2, 109.8, 61.3, 52.6, 31.6, 14.5; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C15H15 Cl2N2O4 [M+H]+: 357.0403; found: 357.0433.

Ethyl 5-[2-(tert-Butoxy)-2-oxoethyl]-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8g)

Yellow oil. 160 mg (0.45 mmol), 89% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.36 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.89 (s, 1H), 4.41 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.57 (s, 2H), 1.40–1.33 (comp, 12H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 168.1, 162.0, 160.1, 143.9, 138.2, 131.9, 127.6, 114.4, 109.8, 82.2, 61.1, 55.8, 32.5, 28.0, 14.6; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C19H25N2O5 [M+H]+: 361.1758; found: 361.1779.

Ethyl 5-[2-(Benzyloxy)-2-oxoethyl]-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8h)

Yellow oil. 173 mg (0.44 mmol), 88% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.37.7.29 (comp, 7H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 5.12 (s, 2H), 4.43 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.72 (s, 2H), 1.42 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 168.8, 162.5, 160.2, 144.0, 137.5, 135.3, 131.7, 128.8, 128.7, 128.6, 127.7, 114.5, 110.1, 67.4, 61.2, 55.8, 32.3, 14.6; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C22H23N2O5 [M+H]+: 395.1601; found: 395.1617.

Ethyl 5-(2-Methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8i)

Yellow solid, mp =107–108 °C. 123 mg (0.37 mmol), 74% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.34 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 4.42 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.67 (s, 3H), 3.61 (s, 2H), 2.31 (s, 3H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 169.5, 163.3, 160.2, 141.6, 135.4, 132.0, 127.7, 120.0, 114.4, 60.8, 55.8, 52.6, 30.6, 14.6, 9.5; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C17H21N2O5 [M+H]+: 333.1445; found: 333.1425.

Ethyl 1-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8j)

Yellow solid, mp = 106–108 °C. 111 mg (0.33 mmol), 66% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.48 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.42 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 4.45 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 3.66 (s, 2H), 2.34 (s, 3H), 1.43 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 169.3, 163.1, 142.4, 137.7, 135.24, 135.18, 129.7, 127.6, 120.6, 61.1, 52.8, 30.7, 14.7, 9.5; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C16H18ClN2O4 [M+H]+: 337.0950; found: 337.0977.

Ethyl 5-[2-(Benzyloxy)-2-oxoethyl]-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8k)

White solid, mp = 111–112 °C. 141 mg (0.34 mmol), 69% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.35 (comp, 7H), 6.89 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 5.12 (s, 2H), 4.44 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.65 (s, 2H), 2.31 (s, 3H), 1.42 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 168.9, 163.2, 160.1, 141.6, 135.5, 135.4, 132.0, 128.8, 128.7, 128.6, 127.8, 120.1, 114.4, 67.4, 60.9, 55.8, 30.9, 14.7, 9.5; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C23H25N2O5 [M+H]+: 409.1758; found: 409.1772.

Ethyl 5-(2-(Benzyloxy)-2-oxoethyl)-4-ethyl-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (8l)

Yellow solid, mp = 78–79 °C. 101 mg (0.24 mmol), 48% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.39–7.29 (comp, 7H), 6.88 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 5.11 (s, 2H), 4.44 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.65 (s, 2H), 2.76 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.42 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.17 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 169.1, 163.0, 160.1, 141.1, 135.4, 134.9, 132.0, 128.8, 128.72, 128.68, 127.8, 126.5, 114.4, 67.4, 60.9, 55.7, 32.7, 17.6, 15.3, 14.6; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C24H27N2O5 [M+H]+: 423.1914; found: 423.1911.

General Procedure for the Deuteration Reactions (Scheme 4)

To an oven-dried flask containing a magnetic stirring bar and hydrazone 5a (0.50 mmol) in DCM (2.0 mL) was added D2O (0.10 mL) at room temperature, and the deuteration experiment of 5a was monitored by 1H NMR (about 10 mins, 5a(H):5a(D) < 5:95). This mixture was used directly for the deuterium tracing study by following the condition of Method B to give deuterated 8a(D) in 81% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.37 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 4.43 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 3.69–3.67 (comp, 4H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 169.4, 162.5, 160.3, 144.1, 137.6, 131.7, 127.7, 114.5, 110.0, 61.2, 55.8, 52.7, 32.1, 14.6.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of 14

To an oven-dried flask containing a magnetic stirring bar, 4 Å molecular sieves (100 mg), Rh2(OAc)4 (2.0 mol %) and hydrazone 5a (0.5 mmol) in dichloromethane (2.0 mL), was added enoldiazoacetate 1d (0.6 mmol) in dichloromethane (1.0 mL) over 1 h via a syringe pump at 0 °C. After addition was complete, the reaction solution was stirred for another 2 h at room temperature and after removal of the solvent under reduced pressure, anhydrous ethanol (2.0 mL) and NaOH (1.0 eq) was added. This solution was stirred overnight under same conditions, and the crude reaction mixture was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (eluent: hexanes:EtOAc = 50:1 to 30:1) to give pure 14 in 59% isolated yield, which was smoothly converted to 8i in 91% yield according to the conditions of Method A.

Ethyl 5-[(tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)oxy]-5-(2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4-methyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate (14)

Yellow solid, mp = 67–68 °C. 137 mg (0.30 mmol), 59% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.34 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 4.40 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.66 (s, 2H), 3.54 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H),, 3.37 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 2.77 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 1.39 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.28 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 0.84 (s, 9H), 0.10 (s, 3H), −0.09 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 169.7, 162.4, 157.0, 144.3, 134.2, 123.4, 114.1, 98.1, 61.2, 55.7, 52.0, 50.4, 39.3, 25.8, 15.3, 14.6, −2.9, −3.9; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C23H37N2O6Si [M+H]+: 465.2415; found: 465.2442.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Pyrazole 8j from 15

This ketone precursor 15 was isolated as byproduct in 16 % yield from the reaction of 1d with 5c under the condition of Method B. To an oven-dried flask containing a magnetic stirring bar, 15 (28.0 mg, 0.08 mmol) in dichloromethane (2.0 mL), was added trifluoroacetic acid(TFA, 1d) at room temperature. The reaction turned out 100% convert to the corresponding pyrazole 8j in 96% isolated yield after stirred overnight under this condition.

(E)-1-Ethyl 6-Methyl 2-[2-(4-Chlorophenyl)hydrazono]-3-methyl-4-oxohexanedioate (15)

Yellow solid, mp = 92–93 °C. 28 mg, 16% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 12.24 (bs, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 4.31 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.96 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (s, 3H), 3.56–3.52 (comp, 2H), 1.42–1.35 (comp, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 200.0, 167.8, 163.0, 141.8, 129.5, 127.6, 127.1, 115.3, 61.6, 52.5, 50.2, 47.5, 14.6, 14.2; HRMS (ESI) calculated for C16H20ClN2O5 [M+H]+: 355.1055; found: 355.1058.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful for the support for this research from the National Institutes of Health (GM 46503).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: NMR spectra of new compounds and X-ray diffraction analysis data of 8c. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Doyle MP, McKervey MA, Ye T. Modern CatalyticMethods for Organic Synthesis with Diazo Compounds. John Wiley & Sins; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML, Beckwith REJ. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2861. doi: 10.1021/cr0200217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Padwa A, Weingarten MD. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:223. doi: 10.1021/cr950022h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Doyle MP, Duffy R, Ratnikov M, Zhou L. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:704. doi: 10.1021/cr900239n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Davies HML, Morton D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1857. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00217h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For reviews, see:

- (2).(a) Selander JN, Fokin VV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2477. doi: 10.1021/ja210180q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nadeau E, Ventura DL, Brekan JA, Davies HML. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:1927. doi: 10.1021/jo902644f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xu X, Hu W, Doyle MP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6392. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Cui X, Xu X, Lu H, Zhu S, Wojtas L, Zhang XP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:3304. doi: 10.1021/ja111334j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang Z, Liu Y, Ling L, Li Y, Dong Y, Gong M, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Wang J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:4330. doi: 10.1021/ja107351d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Takeda K, Oohara T, Shimada N, Nambu H, Hashimoto S. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:13992. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Xu X, Qian Y, Yang L, Hu W. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:797. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03024d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Selected recent examples:

- (3).(a) Doyle MP, Dorow RL, Tamblyn WH. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:4059. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gao D, Zhai H, Parvez M, Back TG. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:8057. doi: 10.1021/jo801621d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wu L, Shi M. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:2296. doi: 10.1021/jo100105k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) González-Bobes F, Fenster MDB, Kiau S, Kolla L, Kolotuchin S, Soumeillant M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:813. [Google Scholar]; (e) Lu L, Lu P, Ma S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:676. [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Padwa A. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:6421. doi: 10.1021/jo901300x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Padwa A. Pure Appl. Chem. 2004;76:1933. [Google Scholar]; c) Padwa A, Brodney MA, Marino JP, Osterhout MH, Price AT. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:67. doi: 10.1021/jo9607267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Honey MA, Pasceri R, Lewis W, Moody CJ. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:1396. doi: 10.1021/jo202201w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhao L, Guan Z, Han Y, Xie Y, He S, Liang Y. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:10276. doi: 10.1021/jo7019465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Seki H, Georg GI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15512. doi: 10.1021/ja107329k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Li Y, Shi Y, Huang Z, Wu X, Xu P, Wang J, Zhang Y. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1210. doi: 10.1021/ol200091k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Xu X, Hu W, Zavalij PY, Doyle MP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:11152. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang X, Xu X, Zavalij PY, Doyle MP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:16402. doi: 10.1021/ja207664r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xu X, Zavalij PJ, Hu W, Doyle MP. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:11522. doi: 10.1039/c2cc36537e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xu X, Shabashov D, Zavalij PY, Doyle MP. Org. Lett. 2012;14:800. doi: 10.1021/ol203331r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Xu X, Ratnikov MO, Zavalij PY, Doyle MP. Org. Lett. 2011;13:6122. doi: 10.1021/ol2026125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wang X, Abrahams QM, Zavalij PY, Doyle MP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:5907. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Qian Y, Xu X, Wang X, Zavalij PJ, Hu W, Doyle MP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:5900. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Xu X, Shabashov D, Zavalij PY, Doyle MP. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:5313. doi: 10.1021/jo3006733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Lian Y, Davies HML. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:11940. doi: 10.1021/ja2051155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lian Y, Hardcastle KI, Davies HML. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:9370. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Valette D, Lian Y, Haydek JP, Hardcastle KI, Davies HML. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:8636. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Smith AG, Davies HML. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:18241. doi: 10.1021/ja3092399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hansen JH, Davies HML. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:457. [Google Scholar]; Davies and coworkers have reported analogous vinylogous reactivity with metal carbenes derived from vinyldiazoacetates, especially styryldiazoacetate:

- (7).Xu X, Zavalij PJ, Doyle MP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:9829. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Fernández M, Uria U, Vicario JL, Reyes E, Carrillo L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:11872. doi: 10.1021/ja3041042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Crespo-Peña A, Monge D, Martín-Zamora E, Álvarez E, Fernández R, Lassaletta JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:12912. doi: 10.1021/ja305209w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).The structure of the product 6a was confirmed by deuterium exchange and 2D HSQC NMR analysis, see Supporting Information for details.

- (11).CCDC 909103 contains the supplementary crystallographic data of 8c for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- (12).(a) Pargellis C, Tong L, Churchill L, Cirillo PF, Gilmore T, Graham AG, Grob PM, Hickey ER, Moss N, Pav S, Regan J. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:268. doi: 10.1038/nsb770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Honma T, Yoshizumi T, Hashimoto N, Hayashi K, Kawanishi N, Fukasawa K, Takaki T, Ikeura C, Ikuta M, Suzuki-Takahashi I, Hayama T, Nishimura S, Morishima H. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:4628. doi: 10.1021/jm010326y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ashton WT, Sisco RM, Dong H, Lyons KA, He H, Doss GA, Leiting B, Patel RA, Wu JK, Marsilio F, Thornberry NA, Weber AE. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:2253. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Genin MJ, Biles C, Keiser BJ, Poppe SM, Swaney SM, Tarpley WG, Yagi Y, Romero DL. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:1034. doi: 10.1021/jm990383f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) Herk T, Brussee J, Nieuwendijk AMCH, Klein PAM, Ijzerman AP, Stannek C, Burmeister A, Lorenzen A. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:3945. doi: 10.1021/jm030888c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Katoch-Rouse R, Pavlova OA, Caulder T, Hoffman AF, Mukhin AG, Horti AG. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:642. doi: 10.1021/jm020157x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Despotopoulou C, Klier L, Knochel P. Org. Lett. 2009;11:3326. doi: 10.1021/ol901208d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) McLaughlin M, Marcantonio C, Chen C-Y, Davies IW. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:4309. doi: 10.1021/jo800321p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Goikhman R, Jacques TL, Sames D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3042. doi: 10.1021/ja8096114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Padwa A, Pearson WH. Synthetic Applications of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry Toward Heterocycles and Natural Products. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]; (g) Schroeder G. M.; Wei D, Banfi P, Cai ZW, Lippy J, Menichincheri M, Modugno M, Naglich J, Penhallow B, Perez HL, Sack J, Schmidt RJ, Tebben A, Yan C, Zhang L, Galvani A, Lombardo LJ, Borzilleri RM. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:3951. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Padwa A, Kulkarni YS, Zhang Z. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:4144. [Google Scholar]; (b) Weiss R, Bess M, Huber SM, Heinemann FW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:4610. doi: 10.1021/ja071316a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fuchibe K, Takahashi M, Ichikawa J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:12059. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ponti A, Molteni G. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:5252. doi: 10.1021/jo0156159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Deng X, Mani NS. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1307. doi: 10.1021/ol800200j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Delaunay T, Genix P, Es-Sayed M, Vors J, Monteiro N, Balme G. Org. Lett. 2010;12:3328. doi: 10.1021/ol101087j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Persson T, Nielsen J. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3219. doi: 10.1021/ol0611088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Hu J, Chen S, Sun Y, Yang J, Rao Y. Org. Lett. 2012;14:5030. doi: 10.1021/ol3022353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Kumar R, Varma D, Mobin SM, Namboothiri Org. Lett. 2012;14:4070. doi: 10.1021/ol301695e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Li P, Wu C, Zhao J, Rogness DC, Shi F. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:3149. doi: 10.1021/jo202598e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Knorr L, Blank A. Ber. 1885;18:311. [Google Scholar]; (b) Robertson J, Hatley RJD, Watkin DJ. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin. Trans. 2000;1:3389. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wurtz NR, Turner JM, Baird EE, Dervan PB. Org. Lett. 2001;3:1201. doi: 10.1021/ol0156796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ballini R, Bosica G, Fiorini G, Giarlo G. Synthesis. 2001:2003. [Google Scholar]; (e) Braun RU, Zeitler K, Müller TJJ. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3297. doi: 10.1021/ol0165185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Arrowsmith J, Jennings SA, Clark AS, Stevens MFG. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:5458. doi: 10.1021/jm020936d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Minetto G, Raveglia LF, Taddei M. Org. Lett. 2004;6:389. doi: 10.1021/ol0362820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For some recent applications of Knorr syntheses see:

- (16).(a) Schmidt A, Habeck T, Kindermann MK, Nieger M. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:5977. doi: 10.1021/jo0344337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Martins MAP, Freitag RA, de Rosa A, Flores AFC, Zanatta N, Bonacorso HG. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1999;36:217. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang Z, Qin H. Green. Chem. 2004;6:90. [Google Scholar]; (d) Fustero S, Román R, Sanz-Cervera JF, Simón-Fuentes A, Cuñat AC, Villanova S, Murguía M. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:3523. doi: 10.1021/jo800251g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).The structure of the product 7i was confirmed by deuterium exchange and 2D HSQC NMR analysis, see Supporting Information for details

- (18).(a) Bach RD, Canepa C, Glukhovtsev MN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:6542. [Google Scholar]; (b) Liang Y, Liu S, Yu Z. Synlett. 2009;6:905. [Google Scholar]; (c) Maercker A, Daub VEE. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:2439. [Google Scholar]; For 1,4-H shift see:; For 1,6-H shift see:

- (19).The structures of 14 was confirmed by 1D-NOE and 2D-SHQC NMR analysis, see Supporting Information for details.

- (20).The pyrazole synthesis via Knorr reaction occurs by the nucleophilic nitrogen attacking the carbonyl carbon, see ref 15 and 16.

- (21).(a) Davies HML, Peng Z-Q, Houser JH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:8939. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ueda Y, Roberge G, Vinet V. Can. J. Chem. 1984;62:2936. [Google Scholar]; (c) Davies HML, Ahmed G, Churchill MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:10774. [Google Scholar]; (d) Schwartz BD, Denton JR, Lian Y, Davies HML, Williams CM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8329. doi: 10.1021/ja9019484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.