Abstract

Through an analysis of Aids National Strategic Plans (NSPs), this study investigated the responses of African governments to the HIV epidemics faced by men who have sex with men (MSM).

NSPs from 46 African countries were systematically analysed, paying attention to (1) the representation of MSM and their HIV risk, (2) inclusion of epidemiologic information on the HIV epidemic amongst MSM and (3) government-led interventions addressing MSM. 34 out of 46 NSPs mentioned MSM. While two-thirds of these NSPs acknowledged vulnerability of MSM to HIV infection, fewer than half acknowledged the role of stigma or criminalisation. Four NSPs showed estimated HIV prevalence amongst MSM, and one included incidence.

Two-thirds of the NSPs proposed government-led HIV interventions that address MSM. Those that did plan to intervene planned to do so through policy interventions, social interventions, HIV prevention interventions, HIV treatment interventions, and monitoring activities.

Overall, the governments of the countries included in the study exhibited little knowledge of HIV disease dynamics amongst MSM and little knowledge of the social dynamics behind MSM’s HIV risk. Concerted action is needed to integrate MSM in NSPs and governmental health policies in a way that acknowledges this population and its specific HIV/AIDS related needs.

Keywords: MSM, HIV, Government Response, NSP, Africa

Introduction

Recently, there has been growing consensus around the need to include men who have sex with men (MSM) in national responses to the HIV epidemic. The 2011-2015 strategy for the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), for instance, sets a goal that sexual transmission of HIV should be reduced by half among men who have sex with men (UNAIDS 2010, p. 9). Important funders of the global response to HIV such as The Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief have also recently undertaken to strengthen the response to HIV as it affects MSM (The Global Fund 2009, PEPFAR 2011). This study investigated the current inclusion of MSM in Aids National Strategic Plans (NSPs) as a way of gauging MSM inclusion in national responses to the HIV epidemic.

Epidemiologic evidence shows increasingly that MSM in Africa face high HIV prevalence rates (Wade et al. 2005, Baral et al. 2007, Sanders et al. 2007, Sandfort et al. 2008, Baral et al. 2009, Gueboguo 2009, Smith et al. 2009, Lane et al. 2011, Rispel et al. 2011), and high HIV incidence rates (Price et al. 2012). The HIV epidemics among MSM in Africa are driven by many factors including the criminalisation of same sex practises (Poteat et al. 2011), and stigma and marginalisation (Geibel et al. 2010). These same factors have been shown to create barriers to HIV-related healthcare services (Niang et al. 2003, Lane et al. 2008, Sharma et al. 2008, Baral et al. 2009, Fay et al. 2011).

NSPs have a central role in coordinating the work of stakeholders in a national response to HIV/AIDS. Strategic planning defines ‘not only the strategic framework of the national response [to the HIV epidemic]… but also the intermediate steps that need to be achieved in order to change the current situation into one that represents the objectives to be reached’ (UNAIDS 1998, p. 3). While the structure and contents of NSPs vary considerably across countries, many include the different components outlined in a comprehensive guidance on AIDS strategic planning released by UNAIDS in 1998. There is a situation analysis component in which the dynamics of the HIV epidemic in that country are examined, a response analysis component in which the past intervention activities of government and other stakeholders are listed and appraised, a strategic plan component which lists the intervention plans of government and other stakeholders, and a resource mobilization component in which the resources that will be dedicated to the response are listed (UNAIDS 1998).

NSPs do not perfectly describe MSM-targeted HIV programming conducted ‘on the ground’. In some countries non-government organisations have responded to the HIV epidemic amongst MSM without the government’s involvement, and in other countries, interventions planned in the NSP might have gone unimplemented. The inclusion and non-inclusion of MSM in the NSPs may furthermore be informed by political considerations, or the stipulations of major funders of the HIV response, and consequently not necessarily represent the views of members of the National Aids Coordinating Authorities (NACAs) that produce them. Finally NACAs might themselves be composed of different stakeholders (government, researchers and civil society) whose goals might not always align, but who have to collectively produce one NSP document nonetheless.

Despite the abovementioned shortcomings, NSPs do contain valuable information. By paying attention to (1) the representation of MSM and their related HIV risk in NSPs, (2) the inclusion of epidemiologic information on the HIV epidemic amongst MSM in NSPs and (3) the extent of governmental involvement in HIV interventions addressing MSM, this study aimed to gain an understanding of how NACAs understand and intervene in the HIV epidemic faced by MSM.

Methods

NSPs were obtained electronically through web searches. For those countries whose NSPs were not available online, members of Departments of Health or NACAs were contacted directly to request an electronic copy of the latest NSP. NSPs were included in the study if the period of implementation included 2011, or if it ended before 2011 and we could not find a later NSP. Two of the NSPs we analysed were in draft form (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia 2009, Republic of The Gambia 2009).

In each NSP, a keyword search was performed to determine whether the NSP mentioned men who have sex with men or not. Keywords used included ‘MSM’, ‘men who have sex with men’, ‘gay’, ‘bisexual’ for English NSPs; ‘HSH’ and ‘hommes ayant des rapports sexuels avec les homes’ for French NSPs; ‘HSH’ and ‘homens que fazem sexo com homens’ for Portuguese NSPs; and ‘homo’ for all three languages. Three readers systematically analysed and summarised the relevant parts of each NSP.

We identified and analysed NSPs from 46 countries. In total, 34 of the NSPs mentioned men who have sex with men. Below, we discuss the content of the NSPs which included MSM.

Results

Representation of MSM

Aids National Strategic Plans that mentioned MSM represented this population in various ways. Below we discuss these different representations, paying special attention to the use of the category of ‘Most At Risk Populations’ (MARPs) and the characterisation of MSM as socially marginalized (including discussions of criminalisation of same-sex behaviour), portrayal of MSM as threats to public health, and acknowledgement of MSM as human rights holders. Much of the information presented below is summarised in Table 1. Table 2 lists the NSPs which did not mention MSM.

Table 1.

NSPs that mentioned MSM

| Country | Period | Representation | Epidemiology | Government-led Interventions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most at Risk | Social Stigma and Marginalisation | Criminalisation | Contribution to Incidence | Population Size | Prevalence | Risk Factors | Past Interventions | Planned Social/Policy Environment Interventions | HIV Prevention and Treatment interventions | |||

| NSPs that mention men who have sex with men | Algeria | 2008-2012 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Angola | 2007-2010 | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Benin | 2006-2010 | NA | ||||||||||

| Comoros | 2008-2011 | |||||||||||

| Congo-Brazzaville | 2009-2013 | NA | ||||||||||

| Congo-Kinshasa | 2010-2014 | ✓ | NA | |||||||||

| Côte d’Ivoire | 2006-2010 | ✓ | NA | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Djibouti | 2008-2012 | NA | ✓ | |||||||||

| Ethiopia | 2009-2014 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Gabon | 2008-2012 | NA | ✓ | |||||||||

| Gambia | 2009-2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Ghana | 2011-2015 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Guinea | 2008-2012 | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Kenya | 2009-2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Lesotho | 2006-2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Liberia | 2010-2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Madagascar | 2001-2006 | NA | ||||||||||

| Malawi | 2010-2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Mauritius | 2010-2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Morocco | 2007-2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Mozambique | 2010-2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Namibia | 2010-2015 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Niger | 2008-2012 | ✓ | NA | |||||||||

| Nigeria | 2010-2015 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| North Sudan | 2010-2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Rwanda | 2009-2012 | ✓ | ✓ | NA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Senegal | 2007-2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Seychelles | 2005-2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Sierra Leone | 2006-2010 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| South Africa | 2007-2011 | ✓ | NA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Swaziland | 2009-2014 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Tanzania | 2008-2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Togo | 2007-2010 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Zimbabwe | 2006-2010 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

Table 2.

NSPs that did not mention MSM

| Country | Period | |

|---|---|---|

| NSPs that did not Mention MSM | Botswana | 2010-2016 |

| Burkina Faso | 2006-2010 | |

| Burundi | 2007-2011 | |

| Cameroon | 2006-2010 | |

| Central African Republic | 2006-2010 | |

| Chad | 2007-2011 | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 2001-2005 | |

| Eritrea | 2003-2007 | |

| Mali | 2006-2010 | |

| Mauritania | 2003-2007 | |

| Uganda | 2007-2010 | |

| Zambia | 2006-2010 |

MSM were represented as especially vulnerable to HIV infection in two-thirds of the NSPs that had any mention of them. Most of these NSPs addressed MSM through the category of ‘Most at Risk Populations’ (MARPs), but some used the categories of ‘Vulnerable Group’, ‘High Risk Group’, or ‘Key Population’. For ease of presentation, in this paper we will use ’MARPs’ to refer to whichever group contained MSM unless otherwise indicated.

A few NSPs (those from Ethiopia, Lesotho, Morocco and Tanzania in particular) had very expansive definitions for the MARPs category. The Tanzania NSP, for instance, defined MARPs as ‘those most vulnerable due to gender inequality, sexual abuse, socio-cultural factors and involvement in illegal practices (women in relationship without control to practice safe sex, women engaging in commercial and transactional sex, sexually abused children, widows and divorcees, men who have sex with men (MSM), prisoners, refugees and displaced persons, people with disabilities and intravenous drug users)’ (United Republic of Tanzania 2007, p. xxiii).

Within each NSP, the MARPs category was not always used consistently. The Ethiopia, Lesotho and Morocco NSPs enumerated different constituents for the MARPs category in different sections of the NSP. ‘Key populations’ in the Lesotho NSP were comprised of ‘Prisoners, Herd boys, Sex workers, Men who have sex with other men and Mobile Populations’ (Kingdom of Lesotho 2009, p. 13) in the Results Framework section of the NSP. In the National Strategic Plan Programme Interventions section, Key Populations included ‘sex workers, migrant labour, and inmates’ (Kingdom of Lesotho 2009). In summary, the MARPs category was used differently across NSPs, and sometimes inconsistently within NSPs. In most instances, the category included a broad selection of subpopulations.

While social stigma and marginalisation of same-sex sexuality is pervasive across the countries included in this study, only a handful of NSPs (10 out of 34) acknowledged this fact. Notably, the Lesotho, Namibia and Rwanda NSPs not only acknowledged stigma, they drew the connection between social stigma and reduced access to HIV services by MSM. These three, as well as the Senegal NSP, also pointed out that stigma makes it more difficult to conduct HIV programming for MSM.

Beyond stigma, criminalisation often plays an important role in shaping the HIV epidemic among MSM. Although in most (24 out of 34) of the countries that mentioned MSM in the NSP, sexual acts between men were criminalised (Bruce-Jones and Itaborahy 2011), at the time of writing few NSPs from those countries (11 out of 24) acknowledged this fact. Amongst those that did, six elaborated on the impact of criminalisation on the HIV epidemic amongst MSM. Criminalisation of same sex sexuality was said to impede access to HIV services for MSM (Republic of Namibia 2010, Republic of the Sudan Undated), to make it more challenging to implement HIV programs for MSM (United Republic of Tanzania 2007, Republic of Kenya 2009) and to contribute to further transmission of HIV (Republic of The Gambia 2009).

The human rights of MSM (or MARPs including MSM) were acknowledged by some NSPs in order to motivate interventions in this population (Kingdom of Lesotho 2009, Republic of Rwanda 2009, Federal Republic of Nigeria 2010, Republic of Namibia 2010, Republic of Ghana 2011, Republic of Liberia Undated). The Lesotho NSP, for instance, asserted that ‘… controlling HIV infection amongst the key populations at risk will not necessarily reduce the overall number of new infections significantly at population level, or prevent the epidemic from sustaining itself. However, it is important to provide services based on a human rights approach and the obligations of the duty bearers’ (Kingdom of Lesotho 2009, p. 40). In five (Ghana, Lesotho, Namibia, Nigeria, and Liberia) of the six countries which drew attention to the human rights of MSM, however, same-sex sexual acts between consenting adults remained criminalised at the time of writing (Bruce-Jones and Itaborahy 2011).

MSM were sometimes presented as a public health threat. Seven of the 34 countries that specifically addressed MSM in their NSP’s presented MSM as a threat to public health due to the HIV transmission risk they were purported to present to female sexual partners (Republic of Zimbabwe 2006, Republic of Malawi 2009, Republic of The Gambia 2009, Republic of Liberia Undated, République De Djibouti Undated). A related way of describing MSM was as a ‘bridge population’ which threatens to ‘further spread [HIV] into the general population’ (Republic of Liberia Undated, p. 12). The NSP for Gambia, for instance, explained that ‘stakeholders at the orientation of this document underscored the importance of recognizing these groups [MARPs including MSM] especially because of their interactions with the general population’ (Republic of The Gambia 2009, p. 36). None of these NSPs referenced epidemiological data that demonstrated the risk posed by MSM.

Basic misunderstandings about same-sex sexuality surfaced in a minority of NSPs. The Gambia NSP which included MSM in the category of MARPs, also discussed MSM through the category of ‘male bumsters’: ‘Bumsters are mainly males who… often believe that their lives can change overnight when they meet a rich tourist who could take them out of the country or enter into a lucrative business venture… they occasionally act as pimps or provide sex themselves to male and female tourists’ (Republic of The Gambia 2009, p. 22).

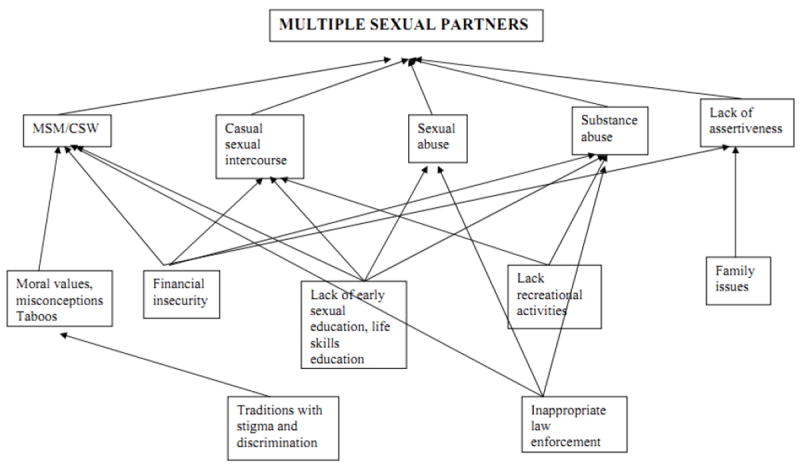

The Seychelles NSP framed homosexuality as a problem that leads to multiple sexual partners (Figure 1) and identified the problem’s antecedents. Homosexuality, according to diagrams in the NSP, arises from ‘financial insecurity’, ‘moral values misconceptions and taboos’, ‘Lack of early sexual education, life skills education’ and ‘Inappropriate Law Enforcement’ (2004, pg. 74). The causes of homosexuality were understood to be the same as the causes of commercial sex work.

Figure 1.

Problem tree for each immediate cause: Multiple sexual partners (République Des Seychelles 2004, p. 74)

‘Situational homosexuality’ emerged as a concern in a handful of NSPs, especially among male prisoners (Republic of Mauritius 2010, Republic of Liberia Undated, Republic of South Africa Undated). According to the Liberia NSP, ‘[a]s a result of long-term confinement to small spaces with other men and without women, unprotected sex among male prison inmates – including high-risk anal sex, and voluntary or forced sex, including rape – is common in most countries in the world, including West Africa’ (p. 2). The South African NSP went further to assert that ‘MSM practices are… more likely to occur in particular institutional settings such as prisons, often underpinned by coercion and violence’ (p. 35).

Epidemiologic Information

Very little information on the epidemiology of HIV among MSM was incorporated in the studied NSPs. Below we discuss the inclusion of estimates of population size, incidence and prevalence in NSPs, and the inclusion of HIV risk factors.

Only three NSPs showed estimates of the population size of MSM: The Namibia NSP cited a World Bank estimate of 2600 MSM in Namibia and the Ghana NSP showed an estimated population size of 13,500. The Nigeria NSP, on the other hand, estimated that sex workers and MSM together comprise 3.5% of the population. Other NSPs gave information that was suggestive of the population size of MSM: the Liberia NSP, for instance, acknowledged ‘the existence of a sizeable and growing community of MSM in Liberia’ (Republic of Liberia Undated, p. 22) citing preliminary data from a study conducted by amfAR. The Gambia NSP showed the estimated size of the entire MARPs population (at 33,050) even though it had a particularly expansive definition for MARPs.

While 12 NSPs showed an estimate of the contribution to population-wide incidence made by MSM, only the Malawi NSP reported an estimate of HIV incidence (of 4.3%) amongst MSM. NSPs from Kenya and Morocco presented region-specific contributions of MSM to overall HIV incidence. The NSP from Kenya, for instance, stated that: ‘MSM contributes to less than 6% of incidence in Nyanza, but over 11% in Nairobi’ (2009, p. 5). The Nigeria NSP only presented the joint contribution of ‘IDUs, FSWs, MSM and their partners’ (Federal Republic of Nigeria 2010, p. 12) to population-wide incidence without specifying the individual contributions of each of those sub-populations.

The only NSPs to report estimates of prevalence amongst MSM were those from Malawi, Senegal, Ghana and North Sudan. They reported prevalence rates of 21%, 25.3%, 21.5% and 9.3% respectively. The prevalence rates reported for Malawi, Senegal and Ghana were established through studies conducted in selected cities. The North Sudan NSP did not give details about the geographical population for which the rate applies.

Twelve NSPs included information on the factors that place MSM at risk for HIV infection. NSPs from Gambia, Ghana, Liberia and Rwanda contained information regarding sexual networks (such as the number, patterning, and geographic distribution of partners, etc.) of MSM and how the networks shape HIV risk. These NSPs linked higher HIV infection risk amongst MSM to higher rates of partner concurrency and commercial or transactional sex. While other NSPs referred to studies that were conducted in-country, the NSP for Liberia referred to data that were collected across countries in West Africa: ‘Available data suggest that high rates of unprotected commercial and non-commercial anal sex occur between MSM in West Africa, with high rates of multiple partners…’ (Republic of Liberia Undated, p. 22).

NSPs also highlighted behaviours such as low condom use (Republic of Malawi 2009, Republic of Rwanda 2009, Republic of The Gambia 2009, Federal Republic of Nigeria 2010, Republic of Ghana 2011, Republic of Liberia Undated, Republic of the Sudan Undated, République Du Sénégal Undated); receptive anal intercourse (Republic of South Africa Undated); and group sex and drug abuse (Republic of Ghana 2011) as contributors to HIV risk amongst MSM.

Finally, sexually transmitted infections were listed as HIV risk factors by the NSPs for Liberia and Rwanda. Both of these NSPs suggested that there was a high prevalence of (untreated) STIs amongst MSM and that this had increased the risk of HIV transmission.

About half (15 out of 34) of the NSPs that mentioned MSM planned to monitor the HIV epidemic amongst MSM (or MARPS including MSM). Most of these NSPs aimed to monitor HIV prevalence (9 out of 15 – see Table 3) and HIV risk factors (12 out of 15). Slightly fewer than half (7 out of 15) aimed to estimate the population size. The NSP for Namibia, for instance, listed a priority action in the section on Prevention of HIV among the Most at Risk Populations (MARPS) and Vulnerable Groups ‘[t]o conduct a nation-wide size estimation and bio-behavioural surveillance of MARPS to inform future planning, service delivery and policy considerations’ (Republic of Namibia 2010, p. 37).

Table 3.

Planned Monitoring Activities

| Country | Period | Monitoring | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | Risk Factors | Population Size | |||

| Monitoring | Algeria | 2008-2012 | ✓ | ||

| Benin | 2006-2010 | ✓ | |||

| Côte d’Ivoire | 2006-2010 | ✓ | |||

| Ethiopia | 2009-2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Ghana | 2011-2015 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Kenya | 2009-2012 | ✓ | |||

| Lesotho | 2006-2011 | ✓ | |||

| Liberia | 2010-2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Morocco | 2007-2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Mozambique | 2010-2014 | ✓ | |||

| Namibia | 2010-2015 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Nigeria | 2010-2015 | ✓ | |||

| Rwanda | 2009-2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Sudan | 2010-2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Tanzania | 2008-2012 | ✓ | |||

Government-led HIV Interventions Addressing MSM

Below we discuss past and future government-led interventions in the HIV epidemic among MSM. Few NSPs (8 out of 34) referred to any government-led activity in the HIV epidemic amongst MSM prior to the implementation period of the NSP. Interventions that were mentioned varied in scale: In Liberia ‘…activities for specific at-risk groups [had] been limited. Examples include women and girls, sex workers… and MSM’ (Republic of Liberia Undated, p. 31). The Tanzania NSP, on the other hand, cited a strategic plan by a government ministry on the ‘protection of women and children, including Commercial Sex Workers, Mobile Population, Injecting Drug Users (IDUs), Men having Sex with Men (MSM), and Single Mothers’ (United Republic of Tanzania 2007, p. 21) which was said to be in implementation. No NSPs discussed prior HIV care and treatment interventions targeting MSM.

A variety of planned HIV interventions among MSM were mentioned by NSPs. A small minority of countries’ NSPs planned a variety of structural or legal interventions aimed at changing the policy environment to be more conducive to HIV prevention efforts with MSM. Only one NSP (from Tanzania) explicitly aimed to decriminalise same-sex sexual activity. Other NSPs that aimed to affect the policy environment discussed different approaches: The Gambia NSP aimed first to gather evidence on which to base advocacy for policy change before beginning with policy advocacy. The Kenya NSP, on the other hand, planned to advocate for the development and enactment of policy to protect MARPS and ‘to create an enabling policy environment for HIV interventions that target these populations’ (Republic of Kenya 2009, p. 14).

A number of NSPs aimed to impact homophobia or stigma targeted at MSM. Some NSPs aimed to reduce stigma against MSM by health care providers (Republic of Rwanda 2009, Republic of The Gambia 2009, Republic of Ghana 2011), and others aimed to reduce stigma amongst the general public (United Republic of Tanzania 2007, Republic of Kenya 2009, República De Moçambique 2010, Republic of Ghana 2011, Republic of Sierra Leone Undated, Republic of South Africa Undated).

Of the 6 NSPs that aimed to reduce stigma amongst the public, only two elaborated on this aim. The NSP for Tanzania aimed to ‘…deepen public awareness, acceptance and understanding of the needs and concerns of PLHIV and other vulnerable and marginalised groups through sustained advocacy at all levels’ (United Republic of Tanzania 2007, p. 44) and also outlined strategies to meet this objective. The NSP for Kenya planned to use ‘[t]argeted, community-based programmes supporting the achievement of Universal Access and social transformation into an AIDS competent society’ (Republic of Kenya 2009, p. 14) citing ‘social mobilisation’ as critical to realising reduced marginalisation of the MARPs. MSM were included in the categories of vulnerable groups and MARPs in the Tanzania NSP and Kenya NSP respectively.

The abovementioned interventions to reduce stigma and improve policy are consistent with recent recommendations by the WHO that protective laws be established to protect MSM, and that health services be made inclusive of MSM. It was noted that these ‘[g]ood practice recommendations are overarching principles derived not from scientific evidence but from common sense and established international agreements on ethics and human rights’ (WHO et al. 2011, p. 29).

HIV prevention interventions were proposed by about half (16 out of 34) of the NSPs that included MSM. All but one of these NSPs – that for Togo – planned to embark on information and education campaigns and behavioural change communication. NSPs aimed to improve access to condoms amongst MSM (United Republic of Tanzania 2007, Republic of Malawi 2009, Republic of Rwanda 2009, Republic of The Gambia 2009, Republic of Ghana 2011, Kingdom of Morocco Undated, Republic of Liberia Undated, Republic of Sierra Leone Undated, Republic of the Sudan Undated); expand HIV testing and counselling (United Republic of Tanzania 2007, Federal Republic of Nigeria 2010, Republic of Namibia 2010, Republic of Ghana 2011, Republic of the Sudan Undated); and improve the treatment of STIs (United Republic of Tanzania 2007, Republic of The Gambia 2009, Republic of Namibia 2010, Republic of Ghana 2011, Republic of the Sudan Undated). The use of condoms and the provision of HIV counselling and testing among MSM were recently strongly recommended as evidence-based interventions by the WHO, and the implementation of individual-level behavioural interventions and of social marketing strategies were conditionally recommended (WHO et al. 2011). The syndromic management and treatment of STIs was consistent with earlier WHO guidance (WHO 2004).

The Ethiopia NSP aimed to ‘provide comprehensive HIV services to MARPS’ including ‘peer education, condom, STI, VCT [voluntary counselling and testing], drug substitution therapy, etc.’ (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia 2009, p. 56). All of the interventions except for peer education are recommended by WHO as evidence-based interventions among MSM (WHO et al. 2011). As mentioned above, however, the MARPs category in the Ethiopia NSP included many different groups, and it was used inconsistently in different sections of the NSP.

Only the Ghana and North Sudan NSPs proposed specific interventions to extend HIV care or treatment to MSM. The North Sudan NSP aimed to develop a communication strategy for ART ‘to identify ways of reaching MARPS [including MSM] and Vulnerable Populations with appropriate information on HIV treatment and care’ (Republic of the Sudan Undated). The Ghana NSP, on the other hand, listed a comprehensive set of interventions: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of opportunistic infections and TB; vaccination, diagnosis and treatment of viral hepatitis; antiretroviral therapy; STI treatment; palliative care including symptom management; home based care; and Nutrition as ‘services essential to reduce vulnerabilities within [the MSM] subgroup’ (Republic of Ghana 2011, p. 23). All of the preceding services, excluding home based care, were listed by the WHO as evidence-based HIV interventions for MSM (WHO et al. 2011).

Discussion

This study analysed African NSPs to gain insight into how African NACAs understand MSM and the epidemic amongst them. Overall, the NACAs of the 34 countries for which MSM were mentioned in the NSP integrated little knowledge of the social dynamics and disease dynamics of HIV in the situation analysis component of the NSP. Despite emerging evidence of the burden of HIV carried by MSM, 12 countries did not include MSM at all in national HIV/AIDS plans.

The use of the category of MARPs was problematic in several NSPs. This category sometimes obfuscated the different needs of populations that constituted MARPs. Most NSPs used ‘MARPs’ to denote MSM along with other vulnerable populations - sex workers and intravenous drug users amongst others. This suggested an acknowledgement by NACAs of the heightened risk of HIV infection faced by these different populations. Many NSPs, however, went on to articulate intervention plans and targets in terms of the MARPs group, and not the constituent sub-populations. Setting targets and proposing interventions for the entire MARPs group, without being more specific, indicates a lack of understanding of the different needs of these groups.

A sensitive and scientific understanding of MSM and the social conditions that make them vulnerable to HIV is key to an appropriate response to the epidemic amongst MSM. It is encouraging that a handful of NACAs demonstrated this understanding through their NSPs; not only did some acknowledge the stigma, marginalisation and criminalisation experienced by MSM, they also elaborated the mechanisms through which these experiences heighten HIV vulnerability. Unfortunately the majority of NACAs failed to acknowledge the central role of stigma and marginalisation, and criminalisation in shaping HIV risk among MSM in Africa.

A handful of NSPs demonstrated some basic misunderstandings of homosexuality – this would likely to lead to inappropriate programming. The NSP for Seychelles, for instance, framed same-sex sexuality in itself as a problem (along with sexual abuse, drug abuse, and others). Other NSPs drew attention to ‘situational homosexuality’ in settings such as prisons. While it is desirable for NSPs to attend to the vulnerabilities of prisoners, imagining all (or most) MSM to have the same vulnerabilities as prisoners, or imagining prisoners to represent all MSM is unhelpful. Fortunately, such basic misunderstandings were limited to a very small number of NSPs.

MSM were sometimes represented as a threat to female sexual partners and the wider population. This threat then motivated intervention in the HIV epidemic among MSM. None of the NSPs that made the assertion that MSM pose heighted risk of HIV infection to female partners supported the assertion with epidemiological evidence from their region. The available evidence form Africa is inconclusive. While it has been suggested that sexual concurrency with both female and male partners may drive the epidemic among MSM (Baral et al. 2009), there is also evidence that the sub-group of MSM that have female sexual partners show lower HIV prevalence rates than MSM who do not have female sexual partners (Lane et al. 2011). While it is important to understand how the MSM epidemics fit into the wider epidemic, framing MSM as a threat to public health suggested that NACAs regarded intervention among MSM as a means to ensure the health of the ‘wider population’ and not necessarily MSM themselves. This framing runs counter to a human rights approach, by which all individuals are entitled to the highest attainable standard of health.

It is encouraging that a number of NSPs did present qualitative information on the epidemiology of HIV among MSM. In general, however, NSPs presented very little quantitative information (such as population size, incidence, or prevalence) on the epidemiology of HIV among MSM. This is worrisome since accurate epidemiologic information is central to an evidence-based response to an HIV epidemic. Available information has not been integrated into NSPs - studies to estimate prevalence among MSM, for instance, have been published in at least 13 of the countries included in this study (Smith et al. 2009) whereas only 4 NSPs presented such estimates. There is a paucity of epidemiologic HIV research among MSM in Africa, and it is troubling that only half of the NSPs that mentioned MSM also mentioned plans to monitor the epidemic in this population.

The criminalisation of same-sex sexuality sometimes created contradictions in NSPs. For instance, some NSPs that either acknowledged the negative public health impact of criminalising MSM or affirmed the human rights of MSM did not call for decriminalisation of same-sex sexuality even though criminalisation is understood to threaten the health (WHO and UNDP 2009) and human rights (Corrêa and Muntarbhorn 2007) of MSM.

Overall, NACAs did not seem to be coordinating the response to the HIV epidemics amongst MSM. Only half of the NSPs proposed to intervene among MSM in the strategic plan component of the NSP, and even fewer referred to earlier government-led interventions among MSM in the response analysis component. Planned interventions were, for the most part, consistent with evidence-based recommendations by the WHO. These interventions tended to be targeted towards proximal determinants of risk (such as availability of condoms, or lack of knowledge of methods of transmission), rather than distal or structural factors (such as homophobia, or criminalisation of same-sex sexuality). Those NSPs that did propose policy changes did so without naming the specific policies that needed to change. There is much room for improvement in the planned response of governments (through their NACAs) to the epidemic.

Concerted effort is needed to sensitise NACAs to the needs of men who have sex with men in regards to the HIV epidemic. The full participation of MSM stakeholders and community members in the strategic planning process might achieve this end. Stakeholders should work to deepen knowledge of the drivers of the epidemic in this population, and to strengthen governmental commitment to halt and reverse the epidemic among all citizens, including men who have sex with men.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the reviewers of Global Public Health for providing critical and constructive feedback on the text.

References

- Baral S, Sifakis F, Cleghorn F, Beyrer C. Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries 2000-2006: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4(12):e339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040339. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18052602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral S, Trapence G, Motimedi F, Umar E, Iipinge S, Dausab F, Beyrer C. HIV prevalence, risks for HIV infection, and human rights among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Malawi, Namibia, and Botswana. PLoS One. 2009;4(3):e4997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004997. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19325707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Jones E, Itaborahy LP. State-sponsored homophobia: a world survey of laws criminalising same-sex sexual acts between consenting adults [online] [15 December 2011];ILGA. 2011 Available from: http://www.ilga.org.

- Burkina Faso. Cadre stratégique de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA et les IST (CSLS) 2006 - 2010 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa S, Muntarbhorn V. The Yogyakarta Principles: principles on the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation and gender identity [online] [30 June 2012];2007 http://www.yogyakartaprinciples.org/principles_en.htm.

- Fay H, Baral SD, Trapence G, Motimedi F, Umar E, Iipinge S, Dausab F, Wirtz A, Beyrer C. Stigma, health care access, and HIV knowledge among men who have sex with men in Malawi, Namibia, and Botswana. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1088–97. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9861-2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21153432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Strategic plan for intensifying multisectoral HIV and AIDS response in Ethiopia II (SPM II) 2009 - 2014 (final draft) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Federal Republic of Nigeria. National HIV/AIDS strategic plan 2010 - 2015 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Geibel S, Tun W, Tapsoba P, Kellerman S. HIV vulnerability of men who have sex with men in developing countries: Horizons studies, 2001-2008. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(2):316–24. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500222. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20297760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueboguo C. Sida et homosexualité(s) en Afrique : analysee des communications de prévention. Études africaines 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom of Lesotho. National HIV and AIDS strategic plan 2006 - 2011 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom of Morocco, Undated. National strategic plan to fight AIDS 2007 - 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom of Swaziland, Undated. The national multi-sectoral strategic framework for HIV and AIDS 2009 - 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Lane T, Mogale T, Struthers H, Mcintyre J, Kegeles SM. ‘They see you as a different thing’: the experiences of men who have sex with men with healthcare workers in South African township communities. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(6):430–3. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031567. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19028941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane T, Raymond HF, Dladla S, Rasethe J, Struthers H, Mcfarland W, Mcintyre J. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Soweto, South Africa: results from the Soweto Men’s Study. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(3):626–34. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9598-y. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19662523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niang CI, Tapsoba P, Weiss E, Diagne M, Nyang Y. ‘It’s raining stones’ : stigma, violence and HIV vulnerability among men who have sex with men in Dakar, Senegal. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2003;5(6):499–512. [Google Scholar]

- Pepfar. Technical guidance on combination HIV prevention [online] [13 January 2012];PEPFAR. 2011 Available from: http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/164010.pdf.

- Poteat T, Diouf D, Drame FM, Ndaw M, Traore C, Dhaliwal M, Beyrer C, Baral S. HIV risk among MSM in Senegal: a qualitative rapid assessment of the impact of enforcing laws that criminalize same sex practices. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028760. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22194906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MA, Rida W, Mwangome M, Mutua G, Middelkoop K, Roux S, Okuku HS, Bekker LG, Anzala O, Ngugi E, Stevens G, Chetty P, Amornkul PN, Sanders EJ. Identifying at-risk populations in Kenya and South Africa: HIV incidence in cohorts of men who report sex with men, sex workers, and youth. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(2):185–193. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823d8693. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22227488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repoblikan’i Madagasikara. Plan stratégique national de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA 2001-2006 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Angola. Plano estratégico nacional para o controlo das infecções de transmissão sexual, VIH e SIDA 2007 a 2010 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Botswana. The second Botswana national strategic framework for HIV and AIDS 2010 - 2016 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Ghana. National strategic plan for most at risk populations 2011 - 2015 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Kenya. Kenya national aids strategic plan 2009/10 - 2012/13 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Liberia, Undated. National HIV strategic framework II 2010 - 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Malawi. National HIV prevention strategy 2009-2013 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Mauritius. Revised national multisectoral HIV and AIDS strategic framework 2010 - 2011 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Namibia. National strategic framework for HIV and AIDS response in Namibia 2010/11 - 2015/16 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Rwanda. National strategic plan for HIV and AIDS 2009-2012 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Sierra Leone, Undated. National HIV/AIDS strategic plan (2006 - 2010) [Google Scholar]

- Republic of South Africa, Undated. HIV & AIDS and STI national strategic plan 2007 - 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of the Gambia. The national HIV and AIDS strategic framework (NSF) for The Gambia: June 2009 - June 2014. Phase: 1 - official draft version 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of the Sudan, Undated. National HIV and AIDS strategic plan (2010 - 2014) [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Uganda, Undated. National HIV & AIDS strategic plan 2007/8 - 2011/12 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Zambia. National HIV and AIDS strategic framework 2006-2010 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe national HIV and AIDS strategic plan (ZNASP) 2006 - 2010 2006 [Google Scholar]

- República De Moçambique. Plano estratégico nacional de resposta ao HIV e SIDA 2010 - 2014 2010 [Google Scholar]

- République Algérienne Démocratique Et Populaire. Plan national stratégique de lutte contre les IST/VIH/SIDA 2008 - 2012 2009 [Google Scholar]

- République Centrafricaine. Cadre stratégique national de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA 2006 - 2010 2006 [Google Scholar]

- République De Côte D’ivoire. Plan stratégique national de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA 2006 - 2010 2006 [Google Scholar]

- République De Djibouti, Undated. Plan stratégique national de lutte contre le VIH 2008-2012 [Google Scholar]

- République De Guinée. Cadre stratégique national 2008 - 2012 2008 [Google Scholar]

- République De Guinée Equatoriale, Undated. Cadre stratégique de lutte contre le SIDA en Guinée Equatoriale 2001 - 2005 [Google Scholar]

- République Démocratique Du Congo. Plan stratégique national de lutte contre le SIDA 2010 - 2014 2009 [Google Scholar]

- République Des Seychelles. National HIV and AIDS strategic plan 2005-2009 2004 [Google Scholar]

- République Du Benin, Undated. Cadre stratégique national de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA/IST 2006 - 2010 [Google Scholar]

- République Du Burundi. Plan stratégique national de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA 2007-2011 2006 [Google Scholar]

- République Du Cameroun, Undated. Plan stratégique national de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA 2006 - 2010 [Google Scholar]

- République Du Congo, Undated. Cadre stratégique national de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA et les IST 2009 - 2013 [Google Scholar]

- République Du Mali. Cadre stratégique national de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA 2006 - 2010 - volume 1 2006 [Google Scholar]

- République Du Niger. Cadre stratégique national de lutte contre les IST/VIH/SIDA 2008 - 2012 2007 [Google Scholar]

- République Du Sénégal, Undated. Plan stratégique de lutte contre le SIDA 2007 - 2011 [Google Scholar]

- République Du Tchad. Cadre stratégique national de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA et les IST 2007 - 2011 2007 [Google Scholar]

- République Gabonaise. Plan stratégique national de lutte contre le SIDA 2008 - 2012 2008 [Google Scholar]

- République Islamique De Mauritanie. Cadre stratégique national de lutte contre les IST/VIH/SIDA 2003 - 2007 2002 [Google Scholar]

- République Togolaise. Plan stratégique national de lutte contre le SIDA et les IST 2007 - 2010 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Rispel LC, Metcalf CA, Cloete A, Reddy V, Lombard C. HIV prevalence and risk practices among men who have sex with men in two South African cities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(1):69–76. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318211b40a. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21297480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders EJ, Graham SM, Okuku HS, Van Der Elst EM, Muhaari A, Davies A, Peshu N, Price M, Mcclelland RS, Smith AD. HIV-1 infection in high risk men who have sex with men in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS. 2007;21(18):2513–20. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2704a. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18025888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort TG, Nel J, Rich E, Reddy V, Yi H. HIV testing and self-reported HIV status in South African men who have sex with men: results from a community-based survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(6):425–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031500. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19028940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Bukusi E, Gorbach P, Cohen CR, Muga C, Kwena Z, Holmes KK. Sexual identity and risk of HIV/STI among men who have sex with men in Nairobi. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(4):352–4. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815e6320. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18360318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AD, Tapsoba P, Peshu N, Sanders EJ, Jaffe HW. Men who have sex with men and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2009;374(9687):416–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61118-1. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19616840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of Eritrea. National Strategic Plan on HIV/AIDS/STIs 2003-2007 2003 [Google Scholar]

- The Global Fund. The Global Fund strategy in relation to sexual orientation and gender identities [online] [2 February 2012]];2009 www.theglobalfund.org.

- Unaids. Guide to the strategic planning process for a national response to HIV/AIDS - Introduction [online] [Accessed 20 June 2012];UNAIDS Information Centre. 1998 Available from: http://data.unaids.org/publications/IRC-pub05/jc441-stratplan-intro_en.pdf.

- Unaids. Getting to zero: 2011 - 2015 strategy [online] [3 March 2012];UNAIDS. 2010 Available from: http://www.unodc.org/documents/eastasiaandpacific/Publications/2011/JC2034_UNAIDS_Strategy_en.pdf.

- Union De Comores. Plan stratégique national de lutte contre les IST/VIH/SIDA 2008-2012 2007 [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. The second national multi-sectoral strategic framework on HIV and AIDS (2008 - 2012) 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Wade AS, Kane CT, Diallo PA, Diop AK, Gueye K, Mboup S, Ndoye I, Lagarde E. HIV infection and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in Senegal. AIDS. 2005;19(18):2133–40. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000194128.97640.07. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16284463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Who. Guidelines for the management of sexually transmitted infections [online] [1 July 2012];WHO. 2004 Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241546263.pdf.

- Who, Unaids, Giz, Msmgf & Undp. Prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex wtih men and transgender people: Recommendations for a public health approach [online] [3 July 2012];WHO. 2011 Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501750_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- Who & Undp. Prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men and transgender populations: Report of a technical consultation 15-17 September 2008 [online] [03 July 2012];WHO. 2009 Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/populations/msm_mreport_2008.pdf.