Abstract

Cyclic peptides hold great potential as therapeutic agents and research tools, but their broad application has been limited by poor membrane permeability. Here, we report a potentially general approach for intracellular delivery of cyclic peptides. Short peptide motifs rich in arginine and hydrophobic residues (e.g., FΦRRRR, where Φ is L-2-naphthylalanine), when embedded into small- to medium-sized cyclic peptides (7–13 amino acids), bound to the plasma membrane of mammalian cultured cells and were subsequently internalized by the cells. Confocal microscopy and a newly developed peptide internalization assay demonstrated that cyclic peptides containing these transporter motifs were translocated into the cytoplasm and nucleus at efficiencies 2–5-fold higher than that of nonaarginine (R9). Furthermore, incorporation of the FΦRRRR motif into a cyclic peptide containing a phosphocoumaryl aminopropionic acid (pCAP) residue generated a cell permeable, fluorogenic probe for detecting intracellular protein tyrosine phosphatase activities.

Keywords: cyclic peptide, cell-penetrating peptide, membrane permeability, membrane transporter, drug delivery

Cyclic peptides are a privileged and yet underexploited class of compounds for drug discovery.1 Compared to their linear counterparts, cyclic peptides have reduced conformational freedom, which makes them more resistant to proteolysis and allows them to bind to their molecular targets with higher affinity and specificity.2–4 They are widely produced in nature and exhibit a broad range of biological activities. In addition, recent technological advances have made it possible to rapidly synthesize and screen large libraries of cyclic peptides against molecular targets or live cells.5–9 Several naturally occurring as well as synthetic cyclic peptides including cyclosporine A, vancomycin, daptomycin, and octreotide are already clinically used as therapeutic agents.

A major limitation to the broader application of cyclic peptides as therapeutic agents or research tools is their poor membrane permeability.10 Most of the clinically used cyclic peptides act on extracellular targets. For example, vancomycin11 and daptomycin12 exert their antibacterial activities against Gram-positive cells by inhibiting the cell wall synthesis and disrupting cell membrane function, respectively. Octreotide is a synthetic analogue of somatostatin and acts by binding to somatostatin receptors at the cell surface.13 It is generally believed that peptides (including cyclic peptides) have poor membrane permeability because the peptide backbone interacts strongly with water molecules through the formation of hydrogen bonds. Desolvation of the peptide bound waters, which is necessary for the peptides to traverse the hydrophobic region of a lipid bilayer, creates a large energy barrier. Some cyclic peptides can lower the desolvation energy by forming intramolecular hydrogen bonds (e.g., a β-turn structure) and are thus more membrane permeable.14 Nα-Methylation of the peptide backbone, which eliminates its hydrogen bonding donor capability and increases the overall hydrophobicity of peptides, also improves their membrane permeability.15,16 Cyclosporine A, a rare example of cyclic peptide drugs that inhibit intracellular targets (i.e., calcineurin),17 contains Nα-methylation at seven out of its eleven peptide bonds. However, most cyclic peptides do not form stable intramolecular hydrogen bonds, whereas Nα-methylation may interfere with target binding and generates a mixture of stereoisomers containing cis/trans peptide bonds, some of which may have undesired biological activities.

Over the past two decades, numerous cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), which typically consist of 6–20 residues, have been found to efficiently translocate the cell membrane.18–24 An important class of CPPs is the arginine-rich peptides [e.g., Tat and nonaarginine (R9)], which have been used to deliver a wide variety of cargoes (from small molecules to large proteins) into mammalian cells. Efficient cargo delivery requires 9–15 arginine residues.25,26 The relatively large size of R9 makes it difficult for direct incorporation into cyclic peptides. Recently, we discovered that some cyclic peptides containing as few as three Arg residues were efficiently internalized by mammalian cells.27 Other investigators also reported enhanced cellular uptake activity upon cyclization of Arg-rich CPPs.28,29 These findings prompted us to further investigate the factors that influence the membrane permeability of cyclic peptides, with the goal of identifying a short peptide motif as a general vehicle for intracellular delivery of cyclic peptides. Herein we report that short sequence motifs (5–6 amino acids) rich in arginine and hydrophobic residues efficiently transport cyclic peptides (including negatively charged phosphopeptides) into the cytoplasm and nucleus of cultured human cells. These peptide motifs may serve as general transporters of cyclic peptides into mammalian cells.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

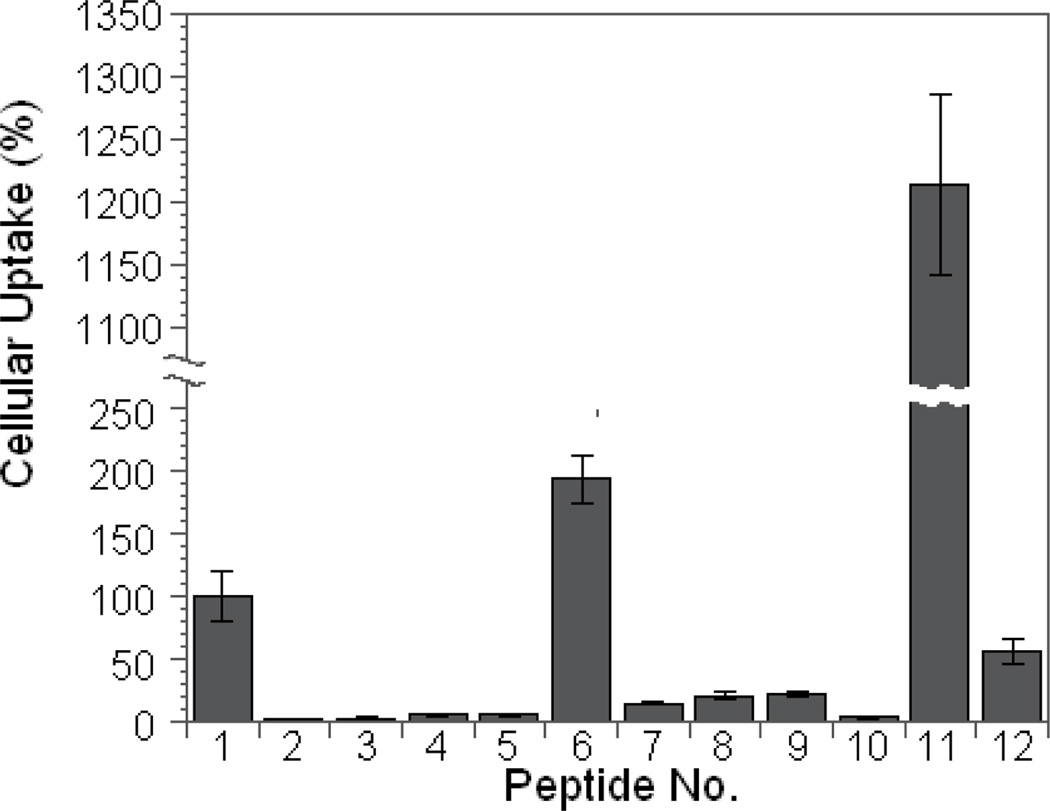

Peptide Cyclization and Hydrophobicity Synergistically Enhance Cellular Association

Our previously reported cell permeable cyclic peptides contained 3–5 Arg residues and at least one aromatic hydrophobic residue [e.g., L-2-naphthylalanine (Nal or Φ)].27 Other investigators have also noted the ability of hydrophobic residues to enhance the membrane transduction activity of CPPs.21,30 To assess the effect of peptide cyclization and hydrophobicity on cellular uptake, we synthesized linear and cyclic forms of tetraarginine (R4), hexaarginine (R6), and FFRRRR (F2R4), along with linear nonaarginine (R9) and cyclo(AAAARRRRQ) (cA4R4) as controls (Table 1, peptides 1–10). All of the cyclic peptides contained a C-terminal Glu residue for peptide cyclization. A Lys residue was added to the Glu side chain and the Lys side chain was labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Figure 1). We initially employed the method of Holm et al.31 to assess the amount of cellular association of these peptides. Each peptide (5 µM) was incubated with MCF-7 human breast cancer cells for 1 h and the cells were washed with buffer and briefly treated with trypsin to remove any peptides bound to the cell surface. The cells were then lysed with NaOH and the amount of fluorescence associated with the cells (which corresponds to the sum of both internalized and any surface-bound peptides) was quantitated. As expected, R9 efficiently translocated into the cells and the amount of internalized peptide was similar to the previously reported values.25,26 R4 had essentially no cellular association, whereas R6 was 17-fold less active than R9 (Figure 2). Replacement of two N-terminal Arg residues of R6 (peptide 5) with Phe (F2R4 or peptide 7) increased the activity by 2.5-fold (Figure 2). Surprisingly, while cyclization of peptides R4 and R6 had no measurable effect (Figure 2, compare peptides 2 vs 3 or 4 vs 5), cyclization of F2R4 increased its cellular association by 14-fold (compare peptides 6 vs 7). As a result, cyclo(FFRRRRQ) (cF2R4, peptide 6) was ~2-fold more active than R9. To ascertain that the increased cellular association was not simply due to the higher proteolytic stability of cyclic peptides, we compared the activities of linear (r6, peptide 9) and cyclic D-hexaarginine peptides (cr6, peptide 8). Although r6 had ~3-fold higher activity than R6, cyclization of r6 did not further increase its cellular association. Moreover, replacement of two Arg residues of cyclic R6 (cR6) with four Ala residues did not increase the amount of peptides associated with the cells (Figure 2, compare peptides 4 and 10). These results suggest that cyclization and hydrophobicity act synergistically to amplify the ability of Arg-rich CPPs to associate with and/or translocate cross the cell membrane. To test whether the cellular association efficiency could be further improved by increasing hydrophobicity, we replaced one of the Phe residues in peptide 6 with 2-naphthylalanine to produce peptide 11, cyclo(FΦRRRRQ) (cFΦR4). Indeed, peptide 11 bound to/internalized MCF-7 cells 23-fold more efficiently than the corresponding linear peptide (peptide 12) and was 13-fold more active than R9 (Figure 2). Similar results were obtained with HEK293 cells, although cyclization of R4, R6, and r6 increased cellular association by 2–3-fold relative to their linear counterparts (Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 1.

Sequences and Cellular Association Efficiency of Linear and Cyclic Peptidesa

| Peptide No. |

Abbreviation | Peptide Sequenceb | Cellular Association (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R9 | Ac-RRRRRRRRRQ-OAll | 100 |

| 2 | cR4 | cyclo(RRRRQ) | 2.5 ± 0.5 |

| 3 | R4 | Ac-RRRRQ-OAll | 2.3 ± 0.8 |

| 4 | cR6 | cyclo(RRRRRRQ) | 5.8 ± 1.1 |

| 5 | R6 | Ac-RRRRRRQ-OAll | 5.8 ± 1.0 |

| 6 | cF2R4 | cyclo(FFRRRRQ) | 190 ± 20 |

| 7 | F2R4 | Ac-FFRRRRQ-OAll | 14 ± 1 |

| 8 | cr6 | cyclo(rrrrrrQ) | 21 ± 3 |

| 9 | r6 | Ac-rrrrrrQ-OAll | 21 ± 2 |

| 10 | cA4R4 | cyclo(AAAARRRRQ) | 3.2 ± 0.2 |

| 11 | cFΦR4 | cyclo(FΦRRRRQ) | 1260 ± 140 |

| 12 | FΦR4 | Ac-FΦRRRRQ-OAll | 55 ± 10 |

| 13 | cAFΦR4 | cyclo(AFΦRRRRQ) | 820 ±210 |

| 14 | cA2FΦR4 | cyclo(AAFΦRRRRQ) | 980 ± 210 |

| 15 | cA3FΦR4 | cyclo(AAAFΦRRRRQ) | 210 ± 70 |

| 16 | cA4FΦR4 | cyclo(AAAAFΦRRRRQ) | 200 ± 40 |

| 17 | cA5FΦR4 | cyclo(AAAAAFΦRRRRQ) | 390 ± 140 |

| 18 | cA6FΦR4 | cyclo(AAAAAAFΦRRRRQ) | 240 ± 100 |

| 19 | cA7FΦR4 | cyclo(AAAAAAAFΦRRRRQ) | 47 ± 5 |

For cellular association assays, all cyclic peptides contained a Lys(FITC)-NH2 attached to the side chain of the invariant Gln residue, and all linear peptides carried a C-terminal allyl group.

r, D-arginine;

, L-2-naphthylalanine.

Cellular association efficiencies were obtained with MCF-7 cells and relative to R9 (100%).

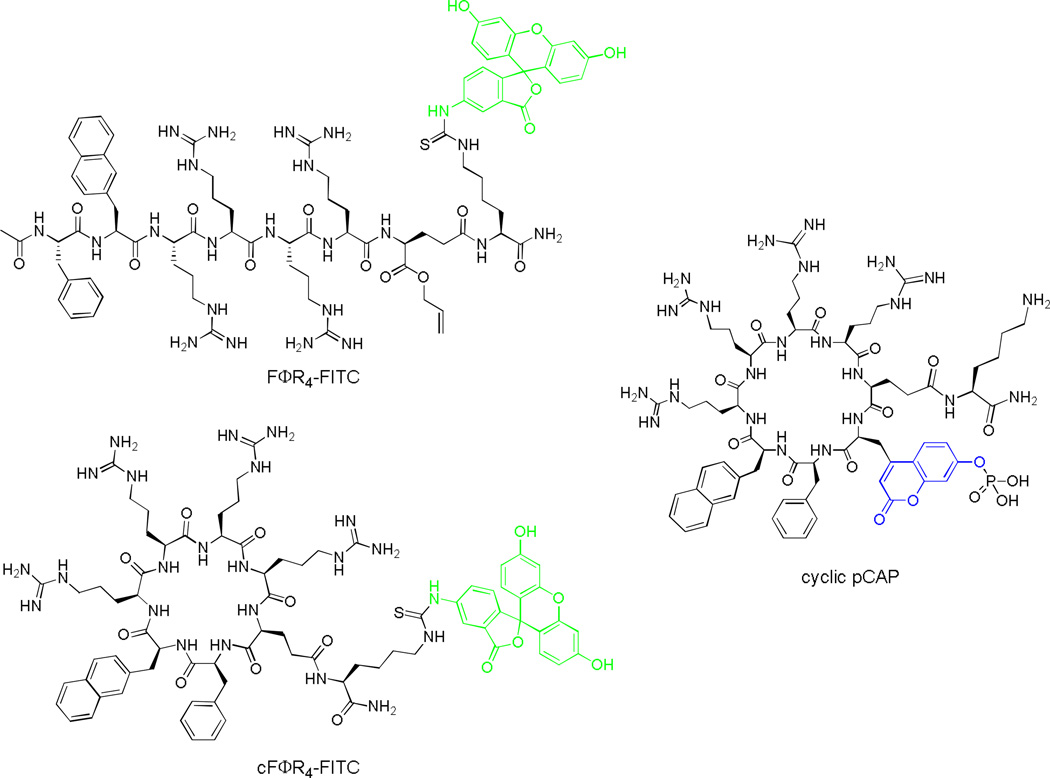

Figure 1.

Structures of FITC-labeled FΦR4 and cFΦR4 and cyclic pCAP peptide.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the cellular association efficiencies of FITC-labeled linear (No. 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 12) and cyclic peptides (No. 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 11) with MCF-7 cells. All values are relative to that of R9 (100%).

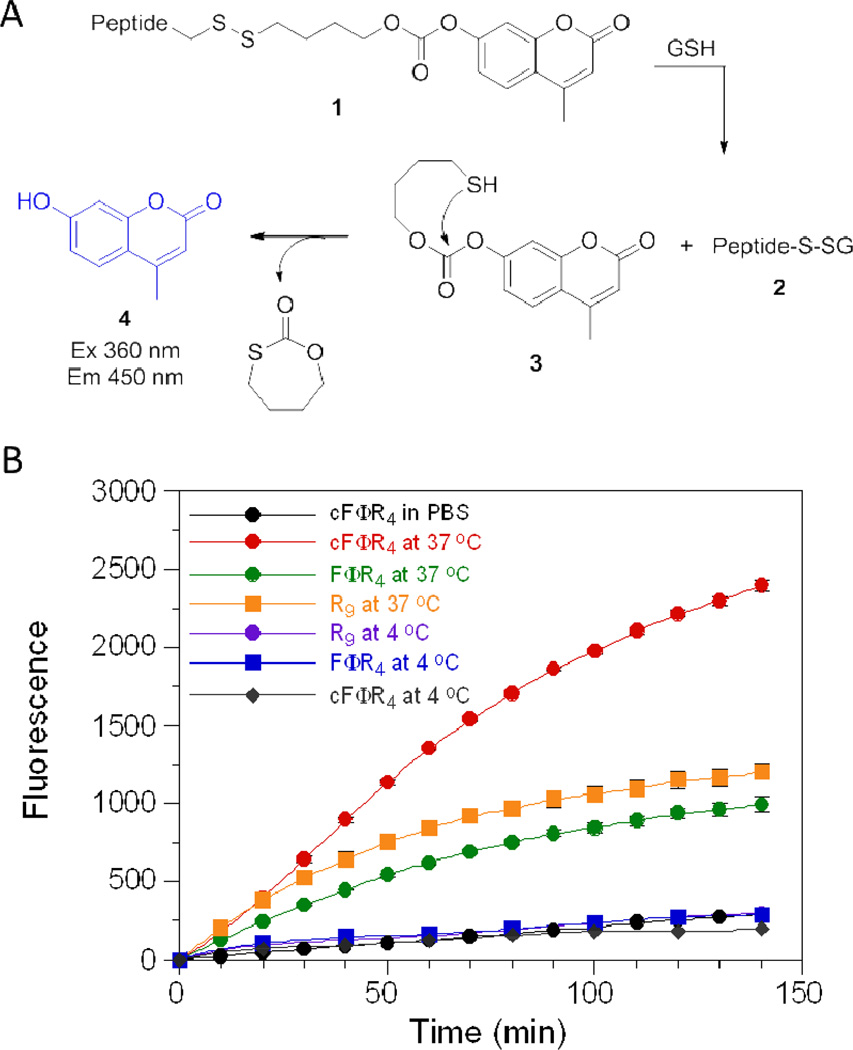

Efficiency and Kinetics of Peptide Internalization

Because the method of Holm et al. does not distinguish internalized versus cell surface-bound CPPs, we modified the method of Wender et al.32 to determine the amount of peptides internalized by the cells. A “caged” fluorophore 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MU) was attached to cyclic peptide cFΦR4 and linear control peptides (FΦR4 and R9) via a disulfide linkage (Figure 3A compound 1). Compound 1 is non-fluorescent and stable in the oxidizing extracellular environment. Upon entering the cell, however, the disulfide bond would be cleaved by the intracellular thiols such as glutathione (GSH) to produce peptide 2 and thiol 3. Under the physiological pH, thiol 3 would undergo spontaneous decomposition to release 4-MU as a fluorescent product. As expected, incubation of MCF-7 cells at 37 °C in the presence of the three peptides all resulted in time-dependent increases in fluorescence intensity (Figure 3B). However, the three peptides were internalized with different efficiency and kinetics. Peptides R9 and cFΦR4 showed similar internalization rates during the first 45 min; after that the internalization of R9 slowed down before reaching a plateau value of 1500 fluorescence units, whereas the translocation of the cyclic peptide continued for several hours and reached 3000 fluorescence units by 6 h (Supplementary Figure S2). Linear FΦR4 showed both lower initial rate and slightly lower final intracellular concentration than R9 (~80%). As a control, incubation of the peptides in PBS (no cells) produced only slight fluorescence increases, due to background hydrolysis of the carbonate ester of compound 1. Addition of 1 mM dithiothreitol into the PBS solution resulted in the complete release of 4-MU in <10 min (Supplementary Figure S3). When MCF-7 cells were incubated with these peptides at 4 °C, the rates of fluorescence increase were similar to the background rate (PBS), indicating the absence of significant peptide internalization (Figure 3B). These results show that cFΦR4 is translocated into mammalian cells ~2-fold more efficiently than R9, one of the most potent CPPs reported to date. The lack of significant translocation at 4 °C suggests that endocytosis may be the primary mechanism of their uptake. Further, the amount of 4-MU released should largely represent the amount of CPPs in the cytoplasm and nucleus. The endosomal and lysosomal environments are more oxidizing than that of the cytoplasm, disfavoring the reduction of disulfides in these organelles.33 There are many examples of unreduced disulfides in the endosome,34–37 although enzymatic reduction of disulfides in the endosomes of antigen-presenting cells has also been reported.38 Background hydrolysis of the carbonate ester linkage of 1 would also lead to 4-MU release; however, the hydrolysis rate decreases with pH (Supplementary Figure S4) and should be minimal in the acidic environments of endosomes (pH 5–7) and lysosomes (pH ~4.8).

Figure 3.

(A) Scheme showing the reduction of the disulfide bond of compound 1 and the release of fluorescent product 4-MU. GSH, glutathione. (B) Time-dependent internalization of indicated peptides (5 µM) by MCF-7 cells at 37 °C or 4 °C.

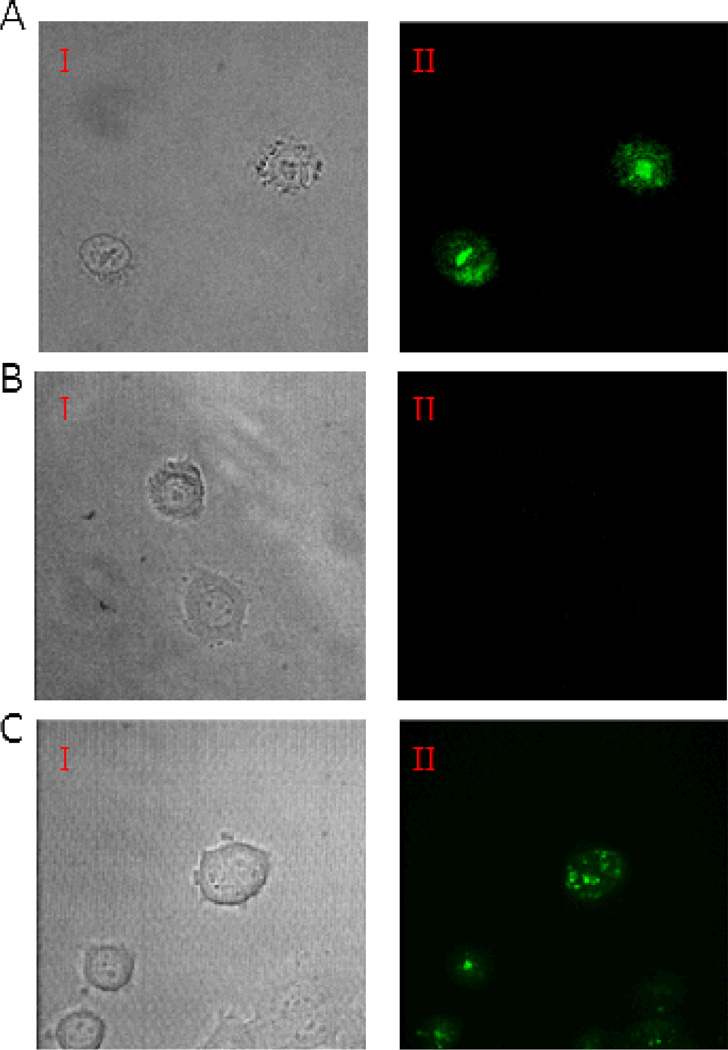

Subcellular Distribution of Internalized Peptides

To obtain further evidence that the cyclic peptides were internalized by mammalian cells, we carried out live-cell confocal microscopy with peptides 1, 11, and 12 (R9, FΦR4, and cFΦR4, respectively). MCF-7 cells were treated with the FITC-labeled peptides (5 µM) for 2 h in the presence of 2% fetal bovine serum and immediately imaged by confocal microscopy. Cells treated with peptides R9 and cFΦR4 showed strong green fluorescence, whereas cells incubated with linear FΦR4 had little intracellular fluorescence under the same imaging conditions (Figure 4). A small amount of fluorescence was detectable at the cell surface when cells were incubated with the linear peptide for 1 h or the incubation was carried out in the absence of serum. Presumably, peptide FΦR4 underwent proteolytic degradation during the 2-h incubation period. The mammalian serum contains high levels of chymotrypsin activity39 and can rapidly degrade linear peptides containing aromatic residues but not the corresponding cyclic peptides.4 Indeed, overnight incubation of peptide FΦR4 in 10% serum resulted in almost complete loss of the full-length peptide. There were notable differences between peptides R9 and cFΦR4. While peptide R9 generated primarily punctate fluorescence, which is in agreement with numerous earlier reports and indicative of endosomal entrapment of the internalized peptide,23,24 cFΦR4 resulted in more diffused signals, consistent with substantial cytoplasmic and nuclear distribution of the latter peptide.

Figure 4.

Live-cell confocal microscopic images of MCF-7 cells treated with FITC-labeled CPPs. (A) Treatment with cFΦR4-FITC I, DIC; II, cFΦR4 distribution in cells. (B) Treatment with FΦR4-FITC I, DIC; II, FΦR4 distribution in cells. (C) Treatment with R9-FITC I, DIC; II, R9 distribution in cells.

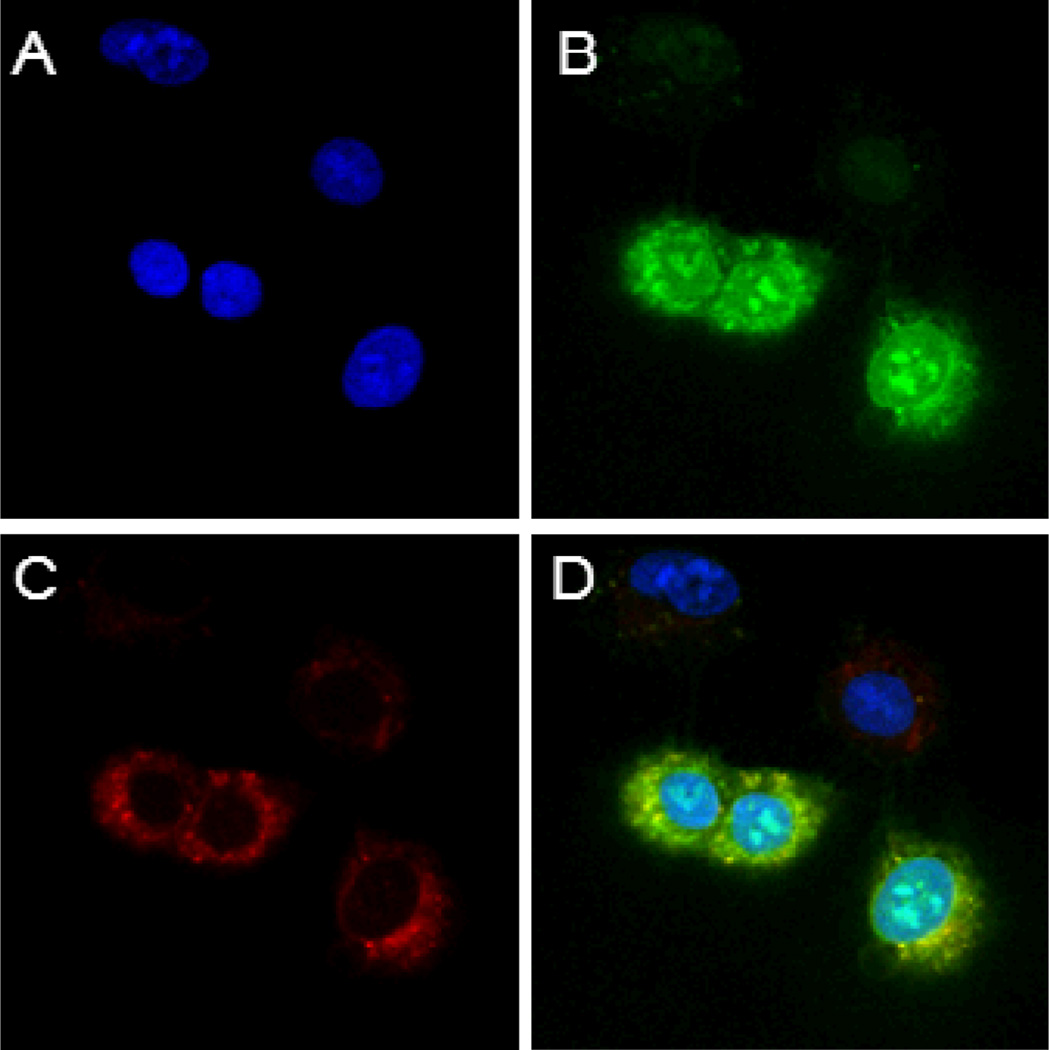

To determine the subcellular distribution of the internalized cyclic peptides, A549 cells (a lung cancer cell line) were incubated simultaneously with FITC-labeled cFΦR4 (5 µM) and rhodamine B-labeled dextran (an endocytosis marker), and then the cell permeable nuclear stain DRAQ5 and examined by confocal microscopy. The internalized cyclic peptide cFΦR4 was distributed throughout the cell and accumulated to a greater extent within nucleoli, whereas rhodamine B remained largely in the cytoplasm (Figure 5). Within the cytoplasmic region, cFΦR4 and the endocytosis marker showed overlapping and punctate fluorescence, suggesting that a fraction of the internalized cyclic peptides were still in the endosomes. All of the cells did not have the same peptide uptake efficiency; ~50% of the cell population exhibited much stronger fluorescence than the rest of the cells (Figure 5). Importantly, the same cell population also internalized the endocytosis marker more efficiently. When the experiment was carried at 4 °C or after the cells had been pre-treated for 1 h with sodium azide (which depletes cells of ATP), the cells failed to take up either the cyclic peptide or the endocytosis marker (Supplementary Figures S5 and S6). These results strongly argue that the cyclic peptides entered the cells through endocytosis, although minor contributions by other mechanisms cannot be ruled out. The accumulation of fluorescence in the nucleus indicates that the internalized peptides were able to escape from the endosomes. The more diffused fluorescence throughout cFΦR4 treated cells and the greater accumulation of cFΦR4 in the nucleoli as compared to R9 also suggest that cFΦR4 is more efficient in endosomal escape than R9, in agreement with the 4-MU assay data (Figure 3). Similar results were obtained when MCF-7 and HEK293 cells were incubated with cyclic peptide cF2R4, whereas linear F2R4 resulted in much weaker intracellular fluorescence, which was primarily located near the membrane periphery (Supplementary Figures S7 and S8).

Figure 5.

Intracellular distribution of cyclic peptide cFΦR4 in A549 lung cancer cells after treatment with cFΦR4-FITC, rhodamine B-dextran, and nuclear stain DRAQ5. A, nuclear stain with DRAQ5; B, green fluorescence of internalized cFΦR4-FITC; C, red fluorescence of rhodamine B-dextran; and D, a merge of A–C.

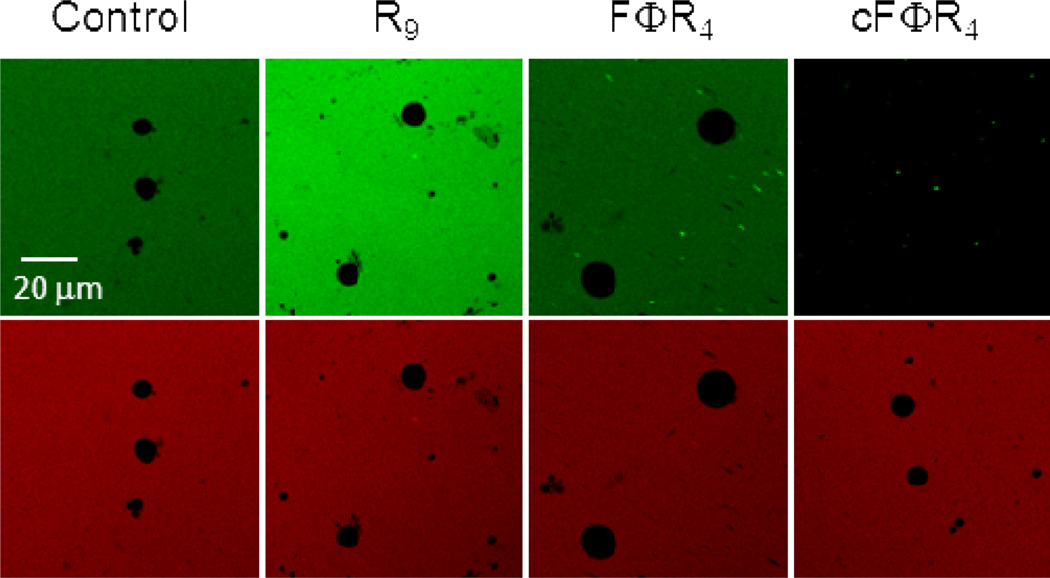

Cyclic Peptides Bind to but Do Not Translocate across Synthetic Membranes

A potential explanation for the apparently conflicting results on the cellular uptake efficiency of cFΦR4 (relative to R9) as measured by the different methods is that a significant fraction of the cyclic CPPs bound tightly to the plasma membrane but did not enter the cells. To test this hypothesis and whether the cyclic CPPs can translocate across membranes in an energy-independent manner, we incubated FITC-labeled cFΦR4, FΦR4, and R9 with multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) containing 90% phosphatidylcholine (PC) and 10% phosphatidylglycerol (PG) (w/w) and monitored peptide internalization by confocal microscopy. Under our assay conditions, no fluorescence could be detected inside the vesicles treated with R9, FΦR4, or the free dyes (fluorescein dextran and TAMRA) (Figure 6). Interestingly, the green fluorescence of cFΦR4-FITC was immediately and almost completely quenched as soon as the peptide and vesicle solutions were mixed. In contrast, the red fluorescence of TAMRA added to the same solution was not affected by the lipids and showed that the vesicles were intact. The same results were obtained with MLVs of more physiologically relevant compositions [45% PC, 20% phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), 20% phosphatidylserine (PS), and 15% cholesterol (w/w)]. The simplest explanation is that most of the cFΦR4-FITC was bound to the vesicle surface and the resulting high local concentration in the membrane caused internal quenching of the fluorescence. These results suggest that cFΦR4 binds directly to the phospholipids with high affinity but cannot cross the membrane in an energy-independent manner. This scenario explains why the cell surface-bound cyclic CPPs were not observed by confocal microscopy. In contrast, the membrane-bound CPPs are readily detected by the method of Holm et al., because cell lysis with NaOH disrupts the cell membranes, releasing the bound CPPs into solution. Linear FΦR4 and R9 likely also interact with the vesicle/cell membranes, but their binding affinities are lower than that of cFΦR4. These linear peptides would be more easily washed off the cell membrane and/or digested by trypsin treatment.

Figure 6.

Confocal microscopic images of PC/PG (90:10) MLVs after incubation with 1 µM free TAMRA dye (red) and 1 µM FITC-labeled dextran (control), R9, FΦR4, or cFΦR4 for 30 min. Top panel, fluorescein channel; bottom panel, TAMRA channel.

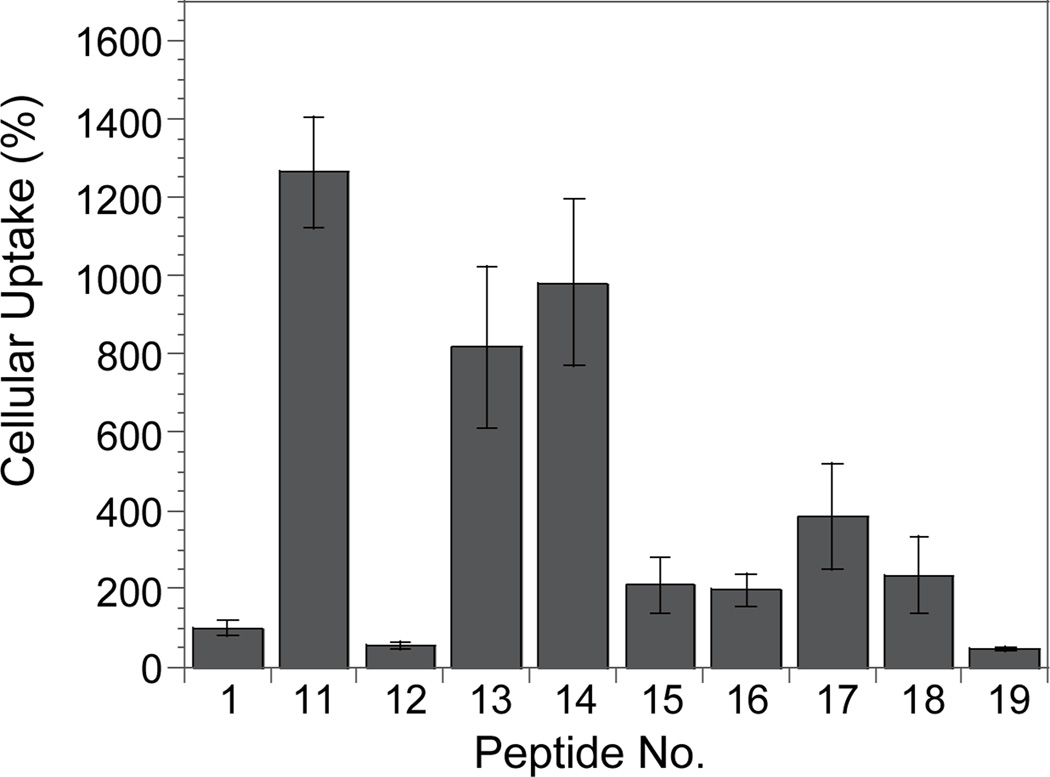

Effect of Ring Size on Membrane Association/Translocation

Taken together, the observations described above suggest the following potential mechanism of CPP uptake. The cyclic peptides bind directly to the phospholipids of the plasma membrane (and possibly other membrane components as well, such as proteins and heparin sulfate) and are internalized as a result of pinocytosis. Based on this mechanism, one would predict that the ring size of the CPPs should have a profound effect on the membrane-binding ability and consequently the cellular association/uptake efficiency. Linear peptides are flexible in solution; binding to a membrane reduces their conformational freedom and the associated entropy loss weakens the overall stability of the peptide-membrane complex. On the other hand, cyclic peptides are more conformationally constrained; a cyclic peptide of the proper sequence may preorganize into the binding conformation in solution and thus bind to the membrane with enhanced affinity. This is indeed the case for cFΦR4, which apparently binds to the MLVs with much higher affinity than FΦR4 (Figure 6). As the ring size of a cyclic peptide increases, however, its conformational freedom increases and the entropic advantage for membrane binding decreases, eventually approaching that of a linear peptide.

To determine what ring sizes confer efficient cellular association/uptake, we synthesized and tested a series of FITC-labeled cyclic peptides that all contained the same transporter motif FΦRRRR but an increasing number of Ala residues (Table 1, peptides 12–19). We chose Ala to expand the ring size because the addition of Ala residues should not significantly change the overall hydrophobicity of the peptide. Indeed, peptides 11 and 13–19 all had virtually identical retention times when analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC (C-18 column). As predicted, peptides of small ring sizes (e.g., 7-, 8-, and 9-amino acids) associated with MCF-7 cells most efficiently, with activities 8–13-fold higher than that of R9 (Figure 7). The medium sized peptides (10- to 13-amino acids) were less active, but still more active than R9. Further increase in the ring size appeared to reduce cellular association, as peptide 19 (14-aa) was comparable to linear peptide Ac-FΦRRRRQ-OAll (peptide 12) and 2-fold less active than R9. We conclude that the observed difference in cellular association was primarily due to the different ring sizes, although we cannot rule out potential contributions by other factors such as small differences in hydrophobicity and/or proteolytic stability.

Figure 7.

Effect of cyclic peptide ring size on their cellular association efficiency by MCF-7 cells (all values are relative to that of R9).

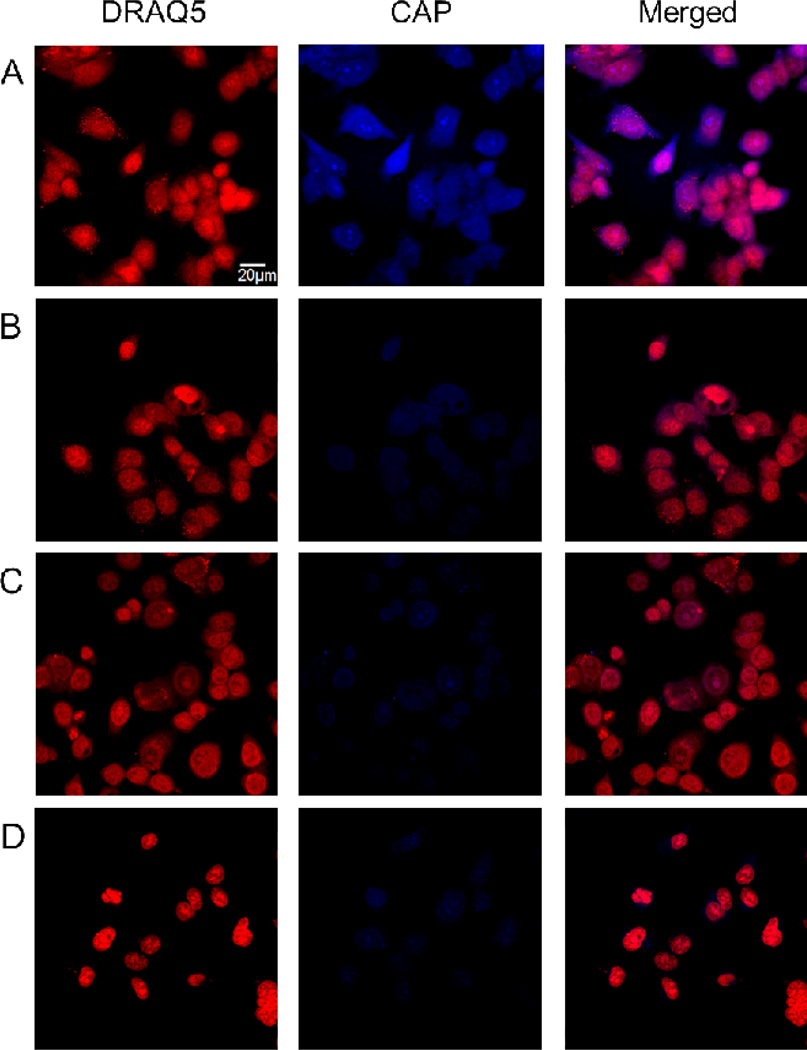

Intracellular Delivery of Phosphopeptides

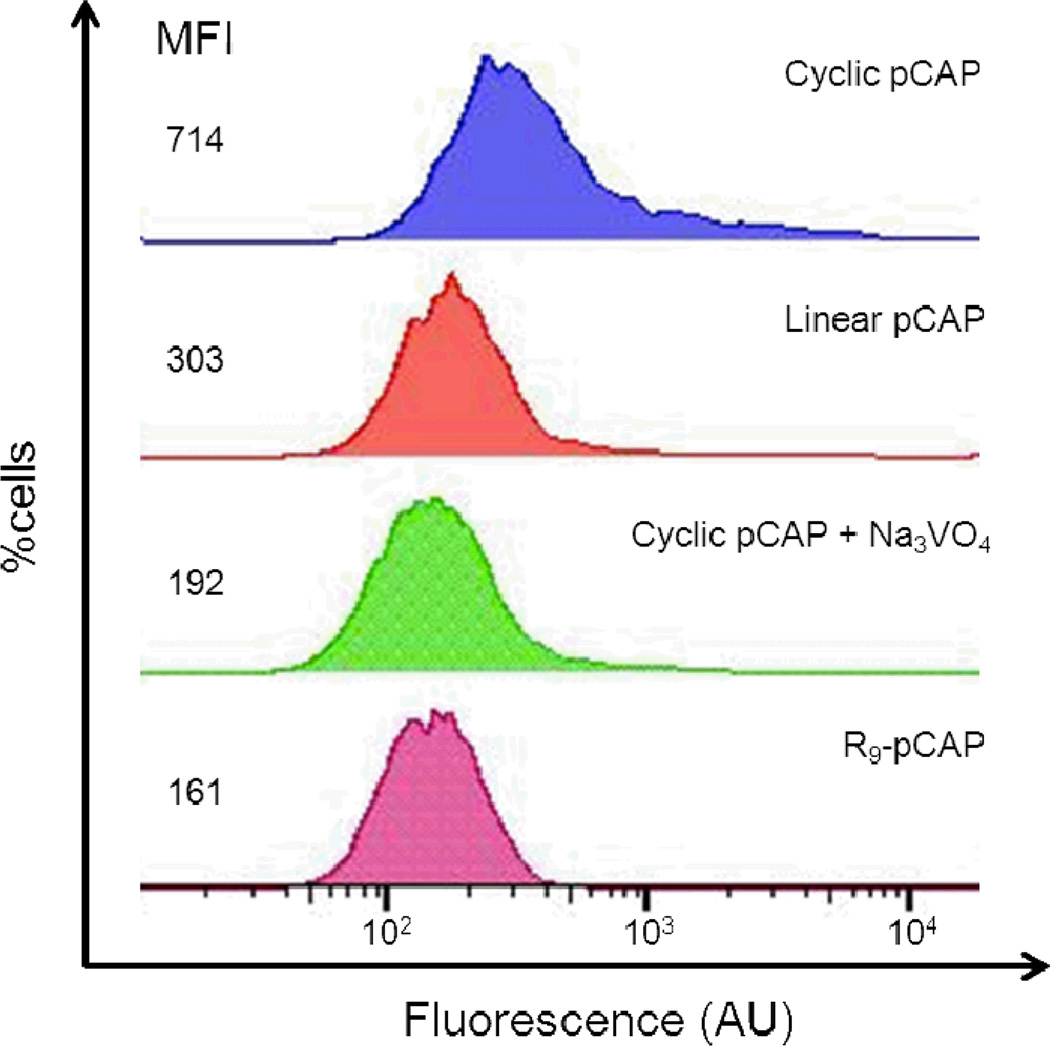

We next examined whether short sequence motifs such as FΦR4 could serve as general transporters of biologically active cyclic peptides into cells. Phosphopeptides, which have extremely poor membrane permeability, were chosen as cargo to rigorously test the efficacy of our transporters. To provide a simple readout for peptide internalization, we used phosphocoumaryl aminopropionic acid (pCAP) as a phosphotyrosine analogue. pCAP is non-fluorescent; however, dephosphorylation of pCAP or pCAP-containing peptides by protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) releases a highly fluorescent coumarin derivative (CAP).40,41 We thus synthesized cyclo[(pCAP)FΦRRRRQ] (Figure 1, cyclic pCAP), the corresponding linear peptide Ac-(pCAP)FΦRRRRQ (linear pCAP), and Ac-(pCap)-β–Ala-RRRRRRRRR (R9-pCAP) and tested their cellular uptake by MCF-7 and HEK293 cells. Treatment of the cells with 5 µM cyclic pCAP for 60 min resulted in blue fluorescence in essentially all of the cells (Figures 8A and Supplementary Figure S9). Furthermore, the blue fluorescence was present in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. In contrast, cells treated with the linear pCAP had much weaker fluorescence under the same conditions (Figures 8B and Supplementary Figure S9). When cells were pretreated with 1 mM sodium pervanadate, a potent PTP inhibitor, followed by 5 µM cyclic pCAP, the amount of CAP fluorescence in the cells was dramatically reduced (Figure 8C and Supplementary Figure S9). Cells treated with R9-pCAP also showed weak fluorescence signal, similar to those of linear pCAP and cells pretreated with sodium pervanadate (Figure 8D). Finally, MCF-7 cells were treated with the above peptides (50 µM) and the amount of peptide uptake was quantitated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Figure 9). The results show that cyclic pCAP was most efficiently taken up by the MCF-7 cells, reaching a mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 714 arbitrary units (AU), whereas linear pCAP and R9-pCAP had 303 and 161 AU, respectively. In vitro assays against a panel of purified recombinant PTPs (PTP1B, TCPTP, SHP-2, RPTPα, and VHR) showed that all three peptides were readily dephosphorylated by these PTPs (Supplementary Table S1). These results indicate that the FΦR4 motif was able to deliver the cyclic phosphopeptide into the mammalian cells and subsequent dephosphorylation of pCAP by endogenous PTPs generated the intracellular fluorescence. Since all known PTPs have their catalytic domains localized in the cytoplasm or nucleus, these data provide further support that the cyclic CPPs can efficiently escape from the endosome and deliver cargos into the cytoplasm and nucleus of mammalian cells. Cyclic pCAP should provide a useful probe for monitoring the intracellular PTP activities.

Figure 8.

Fixed-cell confocal microscopic images of MCF-7 cells treated with pCAP-containing peptides (5 µM each). (A) Cells treated with cyclic pCAP and DRAQ5 in the same Z-section. (B) Same as panel A but with linear pCAP. (C) Same as panel A except that the cells were pretreated with 1 mM sodium pervanadate prior to the addition of cyclic pCAP and DRAQ5. (D) Same as panel A but with R9-pCAP.

Figure 9.

Flow cytometry of MCF-7 cells treated with 50 µM pCAP-containing peptides with and without sodium pervanadate. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Discussion

This work, along with two other recent reports,28,29 demonstrates that cyclization of Arg-rich CPPs enhances their membrane permeability. Our results further reveal that a proper combination of peptide sequence and ring size is critical for efficient cellular uptake. Cyclic peptides containing a proper combination of Arg and hydrophobic residues bind directly to the membrane phospholipids with high affinity and are apparently internalized by pinocytosis. Presumably, interactions between the Arg side chains and the phosphate groups of phospholipids anchor the CPPs on the plasma membrane surface, while the hydrophobic side chains of Phe and Nal residues insert into the hydrophobic region of the membrane and stabilize the peptide-membrane complex by hydrophobic effect. Membrane insertion also helps forming positive membrane curvature, a component of negative Gaussian curvature, which features negative and positive membrane curvatures in two orthogonal dimensions.23,30 All major cellular uptake mechanisms (including endocytosis) involved the formation of negative Gaussian curvatures. According to this model, addition of cyclic CPPs to cells would result in the rapid accumulation of the CPPs on the plasma membrane and the efficiency of peptide internalization would depend on the pinocytosis rate. Since the rate of pinocytosis varies greatly depending on factors such as the cell growth condition (e.g., lower pinocytosis rate at high confluency)42 and the stage in the cell cycle (e.g., higher pinocytosis rate at interphase than metaphase),43 this may explain the varying CPP uptake efficiencies of different cells observed by confocal microscopy. As suggested by the MLV translocation assay, the high peptide concentration within the membrane likely caused fluorescence internal quenching, rendering the membrane-bound peptides undetectable by confocal microscopy. These peptides, which are presumably on the outer leaflet of the membrane, would also evade detection by the 4-MU assay. However, the membrane-bound peptides can be detected by the conventional uptake assay,31 which measures the fluorescence yield after cell lysis. It is yet unclear whether the membrane-bound peptides are limited to the cytoplasmic membrane, or also present on internal membranes (e.g., endosomes).

Short peptide motifs such as FΦR4 provide useful and likely general transporters for intracellular delivery of cyclic peptides. If a target-binding cyclic peptide is already available, one may simply replace the residues noncritical for target binding with FΦR4. The designed cyclic peptides should have ring sizes of 7 to 13 amino acids; larger rings will likely have poor cellular uptake activities, whereas cyclic peptides of <7 residues may not bind to a target with high affinity and specificity. To minimize the ring size, cyclic peptides may be designed so that some of the residues serve the dual function of target binding and membrane transport.27 It is worth noting that phosphopeptides are generally membrane impermeable and notoriously difficult to deliver into cells by other means.44 For example, a recent study showed that intracellular delivery of a pCAP-containing peptide required the combination of a polyarginine sequence and a myristoyl group.41 Remarkably, our cyclic CPPs are 2–5-fold more efficacious than R9 in transporting cargos including phosphopeptides into the mammalian cytoplasm and nucleus, apparently due to a more efficient endosomal escape process. Recent studies suggested that the topology of Arg residues can influence the stage at which a cationic peptide/protein departs the vesicular trafficking pathway to gain cytosolic access.45,46 Cyclization of a polyarginine peptide undoubtedly affects the topology of its Arg residues. Future work will be necessary to test this hypothesis and elucidate the molecular mechanism of cyclic CPP uptake and endosomal escape. Additional advantages of cyclic CPPs include their improved metabolic stability and low cytotoxicity. MTT assays of several cyclic CPPs (including cFΦR4) against 5 different cultured cell lines (MCF-7, HEK293, H1299, H1650, A549) found that the cyclic CPPs in general have no to low levels of cytotoxicity at 50 µM. Since this study only examined a limited number of peptide sequences, it remains to be determined whether additional peptide motifs can be found as efficient membrane transporters.

METHODS

Peptide Synthesis and Labeling

Peptides were synthesized on Rink Resin LS (0.2 mmol/g) using standard Fmoc chemistry. The typical coupling reaction contained 5 equiv of Fmoc-amino acid, 5 equiv of 2-(7-Aza-1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HATU) and 10 equiv of diisoprpylethylamine (DIPEA) and was allowed to proceed at RT with shaking for 75 min. After the addition of the last (N-terminal) residue, the allyl group on the C-terminal Glu residue was removed by treatment with Pd(PPh3)4, PPh3, HCO2H and diethylamine (1, 10, 10, 10 equiv, respectively) in anhydrous THF (overnight at RT). The N-terminal Fmoc group was removed by treatment with 20% piperidine in DMF and the peptide was cyclized by treatment with benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy- tris-pyrrolidino-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP)/HOBt/DIPEA (5, 5, and 10 equiv) in DMF for 3 h. The peptides were deprotected and released from the resin by treatment with 82.5:5:5:5:2.5 (v/v) TFA/thioanisole/water/phenol/ethanedithiol for 2 h. The peptides were triturated with cold Et2O (3×) and purified by reversed-phase HPLC on a C18 column. The authenticity of each peptide was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. FITC labeling was performed by dissolving the purified peptides (~1 mg each) in 300 µL of 1:1:1 DMSO/DMF/150 mM sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.5) and incubating with 10 µL of FITC in DMSO (100 mg ml−1). After 20 min at room temperature, the reaction mixture was subjected to reversed-phase HPLC on a C18 column to isolate the FITC-labeled peptide. pCAP and pCAP-containing peptides were synthesized as previously described.41,42

Cell Culture

MCF-7 cells were maintained in medium consisting of DMEM and Ham's F12 (1:1), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. HEK293 and A549 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Quantification of Peptide Cellular Association

Approximately 1 × 104 MCF-7 cells (or 6 × 103 HEK293 cells) were seeded in 12-well culture plates (BD Falcon) in 1 ml of media and cultured for two days. On the day of experiment, 500 µL of an FITC-labeled peptide solution (5 µM) in HKR buffer (5 mM HEPES, 137 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 2.05 mM MgCl2•6H2O, 1.8 mM CaCl2•2H2O and 1 g/L glucose, pH 7.4) was added to the cells after aspirating the media and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 1 h. The peptide solution was removed by aspiration, and the cells were gently washed with HKR buffer (2 × 1 ml) and treated with 200 µL of 0.25% (w/v) trypsin-EDTA for 10 min. After that, 1 mL of HKR buffer was added and the cells were transferred to a microcentrifuge tube and pelleted by centrifugation. The cell pellet was lysed in 300 µL of 0.1 M NaOH and the FITC fluorescence yield of the cell lysate was determined at 518 nm (with excitation at 494 nm) on a Molecular Devices Spectramax M5 plate reader. For each peptide, a standard line was generated by plotting the fluorescence intensity as a function of peptide concentration in 0.1 M NaOH and the amount of peptides taken up by cells (in pmol) was calculated by using the standard line. The amount of cellular proteins in each well was quantitated by a detergent compatible protein assay (Bio-Rad). Finally, the cellular association efficiency of the FITC-labeled peptide (in pmol of peptide internalized/mg of cellular protein) was calculated by dividing the amount of internalized peptide by the amount of protein in the lysate. The experiments were performed twice and in triplicates each time.

Confocal Microscopy

Approximately 5 × 104 MCF-7 cells were seeded in 35-mm glass-bottomed microwell dish (MatTek) containing 1 mL of media and cultured for one day. MCF-7 cells were gently washed and treated with the FITC-labeled peptide (5 µM) in growth media containing 2% serum for 2 h at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. The peptide-containing media was removed and the cells were washed with PBS three times. The cells were imaged using green and phase contrast channels on a Visitech Infinity 3 Hawk 2D-array live cell imaging confocal microscope (with a 60× oil immersion lens) at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. FITC-labeled peptides were excited at 488 nm and detected with a 520–530 nm band-pass filter.

A549 cells (~5 × 104 cells) were similarly seeded in microwell dishes containing 1 mL of phenol-red free media and cultured overnight. On the day of experiment, the growth medium was removed and the cells were gently washed with PBS twice. The cells were incubated with FITC-labeled peptide (5 µM) and rhodamine B-dextran (1 mg mL−1) in growth media containing 2% serum for 2 h at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. The medium was removed and the cells were gently washed with PBS twice and incubated for 10 min in 1 mL of PBS containing 5 µM DRAQ5. The cells were again washed with PBS twice and imaged as described above.

For fixed-cell confocal microscopic imaging, ~8,000 MCF-7 cells (or 4000 HEK293 cells) were seeded in 8-well chamber slides (Lab-Tek) containing 0.2 mL of media and cultured for one day. On the day of experiment, the growth medium was removed, and the cells were gently washed with PBS twice. The cells were incubated with 0.2 mL of CPP solution (5 µM) at 37 °C for 60 min in the presence of 5% CO2. After removal of the medium, the cells were gently washed with PBS twice and incubated for 10 min in 0.2 mL of PBS containing 5 µM DRAQ5. The resulting cells were washed with PBS twice, fixed by treatment with 0.2 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min on ice and washed with PBS (3 times). The chamber slide was sealed with a coverslip and subjected to confocal imaging on an Olympus FV1000-Filter confocal microscope (with a 60× oil objective). CAP fluorescence was generated with excitation at 405 nm using a diode laser and detected using a DAPI emission filter. All images were recorded by using the same parameters.

MLV Translocation Assay

MLVs were prepared as previously described.47 In each experiment, 10 µL of the lipid solution (18 mM) was mixed with 10 µL of PBS containing 3 µM TAMRA and 10 µL of PBS of 3 µM FITC-labeled peptide. After incubation for 30 min, 4 µL of the mixture was spotted onto a glass coverslip and the slide was imaged on a confocal microscope (Olympus Model FV1000) using a 60× oil objective. MLVs of 5–20 µm in diameter and spherical shape were selected for imaging. Images were recorded at the focal plane at which the vesicles had the largest area in the fluorescein detection mode. The vesicles were imaged using a 488 nm laser and 520 nm bandpass filter for fluorescein and a 543 nm laser with a 580 nm bandpass filter for TAMRA as previously described.47

Flow Cytometry

MCF-7 cells were cultured in six-well plates (5 × 105 cells per well) for 24 h. On the day of experiment, the cells were incubated with 50 µM pCAP-containing peptide in phenol red-free DMEM and Ham's F12 (1:1) supplemented with 0.5% FBS. After 15 min, the peptide solution was removed, and the cells were washed with sodium pervanadate containing DPBS, treated with 0.25% trypsin for 5 min, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (w/v) at room temperature for 15 min, and stained with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Far Red Dead Cell Stain Kits (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, the cells were resuspended in the flow cytometry buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACS Aria III), with excitation at 355 nm.

CPP Internalization by 4-MU Assay

MCF-7 cells (~1 × 104 cells) were seeded in a 96-well plate and cultured for 36 h. The media were removed and the cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 100 µL of 4-MU-labeled peptides in pH 8.0 PBS (5 µM) at 37 or 4 °C. The fluorescence intensity in each well was recorded every 10 (37 °C) or 20 min (4 °C) over a 150-min period on a Molecular Devices Spectramax M5 plate reader (with excitation and emission wavelengths at 360 and 450 nm, respectively). Experiments were performed in quadruplicates and a control experiment was performed without cells. The average fluorescence intensity, after subtraction of the background signal derived from the no-cell control, was plotted as a function of time.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank K. Zhao and G. C. L. Wong of UCLA for input on CPP design and S. Cole, B. Kemmenoe, N. G. Selner and R. Luechapanichkul for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants (GM062820 and CA132855).

Abbreviations

- CPP

cell-penetrating peptide

- cFΦR4

cyclo(FΦRRRRQ)

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- 4-MU

4-methylumbelliferone

- MLV

multilamellar vesicle

- Φ

L-2-naphthylalanine

- PTP

protein tyrosine phosphatase

- pCAP

phosphocoumaryl aminopropionic acid

- R9

nonaarginine

Footnotes

Supporting Information:

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Driggers EM, Hale SP, Lee J, Terrett NK. The exploration of macrocycles for drug discovery - an underexploited structural class. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:608–624. doi: 10.1038/nrd2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szewczuk Z, Gibbs BF, Yue SY, Purisima EO, Konishi Y. Conformationally restricted thrombin inhibitors resistant to proteolytic digestion. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9132–9140. doi: 10.1021/bi00153a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu X, Nguyen KT, Jiang VC, Lofland D, Moser HE, Pei D. Macrocyclic inhibitors for peptide deformylase: An SAR study of the ring size. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:4941–4949. doi: 10.1021/jm049592c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen LT, Chau JK, Perry NA, de Boer L, Zaat SAJ, Vogel HJ. Serum stabilities of short tryptophan- and arginine-rich antimicrobial peptide analogs. Plos ONE. 2010;5:e12684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millward SW, Takahashi TT, Roberts RW. A general route for post-translational cyclization of mRNA display libraries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14142–14143. doi: 10.1021/ja054373h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tavassoli A, Benkovic SJ. Genetically selected cyclic-peptide inhibitors of AICAR transformylase homodimerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2005;44:2760–2763. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joo SH, Xiao Q, Ling Y, Gopishetty B, Pei D. High-throughput sequence determination of cyclic peptide library members by partial Edman degradation/mass spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13000–13009. doi: 10.1021/ja063722k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawakami T, Ohta A, Ohuchi M, Ashigai H, Murakami H, Suga H. Diverse backbone-cyclized peptides via codon reprogramming. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:888–890. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleiner RE, Dumelin CE, Tiu GC, Sakurai K, Liu DR. In vitro selection of a DNA-templated small-molecule library reveals a class of macrocyclic kinase inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11779–11791. doi: 10.1021/ja104903x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon Y-U, Kodadek T. Quantative comparison of the telative cell permeability of cyclic and linear peptides. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:671–677. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen NE, Nicas TI. Mechanism of action of oritavancin and related glycopeptide antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003;26:511–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2003.tb00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hancock RE. Mechanisms of action of newer antibiotics for Gram-positive pathogens. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005;5:209–218. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reubi JC, Waser B, Schaer JC, Laissue JA. Somatostatin receptor sst1-sst5 expression in normal and neoplastic human tissues using receptor autoradiography with subtype-selective ligands. EurJNucl. Med. 2001;28:836–846. doi: 10.1007/s002590100541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rezai T, Yu B, Millhauser GL, Jacobson MP, Lokey RS. Testing the conformational hypothesis of passive membrane permeability using synthetic cyclic peptide diastereomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2510–2511. doi: 10.1021/ja0563455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chatterjee J, Gilon C, Hoffman A, Kessler H. N-Methylation of Peptides: A New Perspective in Medicinal Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1331–1342. doi: 10.1021/ar8000603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White TR, Renzelman CM, Rand AC, Rezai T, McEwen CM, Gelev VM, Turner RA, Linington RG, Leung SSF, Kalgutkar AS, Bauman JN, Zhang YZ, Liras S, Price DA, Mathiowetz AM, Jacobson MP, Lokey RS. 24 On-resin N-methylation of cyclic peptides for discovery of orally bioavailable scaffolds. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:810–817. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J, Farmer JD, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. Calcineurin Is a Common Target of Cyclophilin-Cyclosporine-a and FKBP-FK506 Complexes. Cell. 1991;66:807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green M, Loewenstein PM. Autonomous functional domains of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus tat trans-activator protein. Cell. 1988;55:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankel AD, Pabo CO. cellular uptake of the tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus. Cell. 1988;55:1189–1193. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wender PA, Mitchell DJ, Pattabiraman K, Pelkey ET, Steinman L, Rothbard JB. The design, synthesis, and evaluation of molecules that enable or enhance cellular uptake: Peptoid molecular transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:13003–13008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fillon YA, Anderson JP, Chmielewski J. Cell Penetrating Agents Based on a Polyproline Helix Scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11798–11803. doi: 10.1021/ja052377g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou P, Wang M, Du L, Fisher GW, Waggoner A, Ly DH. Novel Binding and Efficient Cellular Uptake of Guanidine-Based Peptide Nucleic Acids (GPNA) JAm. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6878–6879. doi: 10.1021/ja029665m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt N, Mishra A, Lai GH, Wong GCL. Arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides. FEBS Letters. 2010;584:1806–1813. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langel Ü. Cell-penetrating peptides : methods and protocols. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2011. p. xv.p. 586. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell DJ, Kim DT, Steinman L, Fathman CG, Rothbard JB. Polyarginine enters cells more efficiently than other polycationic homopolymers. J. Pept. Res. 2000;56:318–325. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2000.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goun EA, Pillow TH, Jones LR, Rothbard JB, Wender PA. Molecular transporters: Synthesis of oligoguanidinium transporters and their application to drug delivery and real-time imaging. Chembiochem. 2006;7:1497–1515. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu T, Liu Y, Kao HY, Pei D. Membrane permeable cyclic peptidyl inhibitors against human peptidylprolyl isomerase Pin1. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:2494–2501. doi: 10.1021/jm901778v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lattig-Tunnemann G, Prinz M, Hoffmann D, Behlke J, Palm-Apergi C, Morano I, Herce HD, Cardoso MC. Backbone rigidity and static presentation of guanidinium groups increases cellular uptake of arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:453. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandal D, Shirazi AN, Parang K. Cell-Penetrating Homochiral Cyclic Peptides as Nuclear-Targeting Molecular Transporters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:9633–9637. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mishra A, Lai GH, Schmidt NW, Sun VZ, Rodriguez AR, Tong R, Tang L, Cheng JJ, Deming TJ, Kamei DT, Wong GCL. Translocation of HIV TAT peptide and analogues induced by multiplexed membrane and cytoskeletal interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:16883–16888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108795108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holm T, Johansson H, Lundberg P, Pooga M, Lindgren M, Langel U. Studying the uptake of cell-penetrating peptides. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1001–1005. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones LR, Goun EA, Shinde R, Rothbard JB, Contag CH, Wender PA. Releasable luciferin-transporter conjugates: Tools for the real-time analysis of cellular uptake and release. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6526–6527. doi: 10.1021/ja0586283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Go Y-M, Jones DP. Redox compertmentalization in eukaryotics cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1780:1273–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins DS, Unanue ER, Harding CV. Reduction of disulfide bonds within lysosomes is a key step in antigen processing. J. Immunol. 1991;147:4054–4059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feener EP, Shen WC, Ryser HJ. Cleavage of disulfide bonds in endocytosed macromolecules - a processing not associated with lysosomes or endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:18780–18785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Austin CD, Wen XH, Gazzard L, Nelson C, Scheller RH, Scales SJ. Oxidizing potential of endosomes and lysosomes limits intracellular cleavage of disulfide-based antibody-drug conjugates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:17987–17992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509035102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sauer AM, Schlossbauer A, Ruthardt N, Cauda V, Bein T, Brauchle C. Role of endosomal escape for disulfide-based drug delivery from colloidal mesoporous silica evaluated by live-cell imaging. Nano Lett. 2010;10:3684–3691. doi: 10.1021/nl102180s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arunachalam B, Phan UT, Geuze HJ, Cresswell P. Enzymatic reduction of disulfide bonds in lysosomes: characterization of a Gamma-interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase (GILT) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:745–750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heng MCY, Barrascout CE, Rasmus W, O'Brien W, Song MK. Elevated serum chymotrypsin levels in a patient with junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Inter. J. Dermat. 1987;26:385–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitra S, Barrios AM. Highly sensitive peptide-based probes for protein tyrosine phosphatase activity utilizing a fluorogenic mimic of phosphotyrosine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:5142–5145. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanford SM, Panchal RG, Walker LM, Wu DJ, Falk MD, Mitra S, Damle SS, Ruble D, Kaltcheva T, Zhang S, Zhang Z-Y, Bavari S, Barrios AM, Bottini N. High-throughput screen using a single-cell tyrosine phosphatase assay reveals biologically active inhibitors of tyrosine phosphatase CD45. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:13972–13977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205028109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roederer M, Mays RW, Murphy RF. Effect of confluence on the endocytosis by 3T3 fibroblasts: increased rate of pinocytosis and accumulation of residual bodies. Eur. J. Cell. Biol. 1989;48:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raucher D, Sheetz MP. Membrane expansion increases endocytosis rate during mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:497–506. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shakespeare WC. SH2 domain inhibition: a problem solved? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2001;5:409–415. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fischer R, Kohler K, Fotin-Mleczek M, Brock R. A Stepwise Dissection of the Intracellular Fate of Cationic Cell-penetrating Peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12625–12635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Appelbaum JS, LaRochelle JR, Smith BA, Balkin DM, Holub JM, Schepartz A. Arginine Topology Controls Escape of Minimally Cationic Proteins from Early Endosomes to the Cytoplasm. Chem. Biol. 2012;19:819–830. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marks JR, Placone J, Hristova K, Wimley WC. Spontaneous Membrane-Translocating Peptides by Orthogonal High-Throughput Screening. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8995–9004. doi: 10.1021/ja2017416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.