Abstract

It is estimated that 5–10% of all cutaneous malignancies involve the periocular region and management of periocular skin cancers account for a significant proportion of the oculoplastic surgeon's workload. Epithelial tumours are most frequently encountered, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and sebaceous gland carcinoma, in decreasing order of frequency. Non-epithelial tumours, such as cutaneous melanoma and Merkel cell carcinoma, rarely involve the ocular adnexae. Although non-surgical treatments for periocular malignancies are gaining in popularity, surgery remains the main treatment modality and has as its main aims tumour clearance, restoration of the eyelid function, protection of the ocular surface, and achieving a good cosmetic outcome. The purpose of this article is to review the management of malignant periocular tumours, with particular emphasis on surgical management.

Keywords: eyelid neoplasms, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, Mohs surgery, reconstruction

Introduction

Skin malignancies account for nearly one-third of all newly diagnosed cancers,1 and it is estimated that about 5–10% of them occur in the periocular region.2 Furthermore, periocular skin cancers account for >90% of ophthalmic tumours.3 Therefore, it is essential that all ophthalmologists are able to recognize the features of malignant periocular skin cancer and be aware of the treatment modalities. Although non-surgical treatments for periocular skin cancers are gaining in popularity, surgery remains the main modality of treatment and the surgical management of periocular skin cancer represents a significant proportion of the oculoplastic surgeon's workload. In this review, the features of periocular skin cancer are presented together with a discussion of the treatment modalities.

Diagnosing malignant eyelid disease

Although malignant eyelid disease is usually easy to diagnose on the basis of the history and clinical signs identified on careful examination (Table 1), differentiating between benign and malignant periocular skin lesions can be challenging because malignant lesions occasionally masquerade as benign pathology. For instance, a cystic basal cell carcinoma (BCC) can resemble a hidrocystoma4, 5 or sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) classically mimics a chalazion.6, 7 Conversely, a benign lesion such as a pigmented hidrocystoma may be mistaken for a malignant melanoma.8 Therefore, an eyelid biopsy is often required to make the correct diagnosis. For small lesions, excision biopsy with a suitable margin might be appropriate, but larger lesions require an incisional biopsy. Punch biopsy is a simple technique, which has a role in the diagnosis and management of periocular skin tumours.9, 10, 11

Table 1. Clinical features of malignant eyelid disease.

| Loss of lashes |

| Distortion of eyelid margin |

| Pearly appearance (BCC) |

| Telangiectasia |

| Ulceration |

| Induration |

| Eyelid cicatrization and secondary ectropion/retraction |

| Increasing pigmentation, especially of recent onset |

Malignant eyelid tumours

Most malignant periocular tumours derive from epithelial cells (Table 2) and non-epithelial malignant eyelid tumours are fairly rare. Therefore, the discussion that follows focusses mostly on the epithelial tumours, except for malignant melanoma.

Table 2. Classification of malignant eyelid tumours.

| Epithelial | Non-epithelial |

|---|---|

| BCC | Malignant melanoma |

| SCC | Merkel cell tumour |

| Sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) | Kaposi sarcoma |

| Metastases | |

| Lymphoma | |

| Microcystic adnexal carcinoma | |

| Malignant sweat gland tumours |

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

BCC accounts for the vast majority of periocular tumours (90–95%).12 They derive from the basal layer of the epidermis, have ultraviolet (UV) light exposure as an important aetiological factor and occur almost exclusively in fair-skinned patients.13, 14 The mean age of incidence is in the seventh decade, with a slight male preponderance, but they are increasingly seen in younger age groups because of excessive sun exposure or UV light from sun beds.15, 16 The lower lid is the commonest location, followed by the medial canthus, with the upper lid rarely involved.2, 12

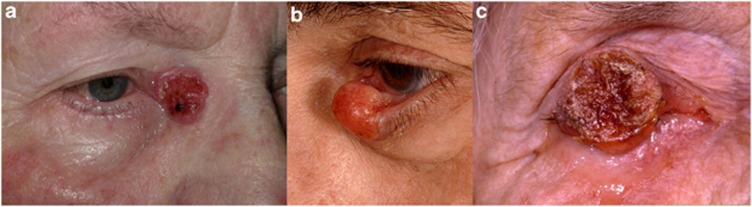

On the basis of their clinical appearance BCCs can be classified into several clinical subtypes (Table 3), the commonest of which is the nodular BCC,2, 12 which presents as a well circumscribed, pearly lump with surface telangiectasia (Figure 1a). With progression they usually ulcerate with resultant bleeding and crust formation (Figure 1b), or they may undergo cystic degeneration (Figure 1c). In contrast to nodular BCCs, morpheaform (or morpheic) BCCs have poorly defined margins (Figure 1d). Occasionally BCCs are pigmented (Figure 1e) or have a linear morphology.

Table 3. Clinical varieties of BCC.

| Nodular |

| Nodulo-ulcerative |

| Morpheaform |

| Cystic |

| Pigmented |

| Linear |

Figure 1.

Morphological varieties of BCC. (a) Nodular, (b) noduloulcerative, (c) cystic, (d) extensive morpheaform BCC with ulceration and orbital invasion, and (e) pigmented BCC in lash line with adjacent pigmented intradermal naevus on lid margin.

The clinical behaviour of BCCs is largely determined by their histological subtype (Table 4). In a study of 1039 BCCs, Sexton et al17 found that aggressive histological subtypes like micronodular, infiltrative, and morpheaform BCCs had a higher incidence of positive tumour margins (18.6, 26.5, and 33.3%, respectively) after excision compared with nodular and superficial BCCs, which were fully excised in >90% of cases.

Table 4. Histological subtypes of BCC.

| Nodular |

| Morpheaform |

| Infiltrative |

| Superficial spreading |

| Micronodular |

| Mixed |

The poor prognostic factors for BCC, in addition to histopathological subtype, are summarized in Table 5. Medial canthal tumours have a tendency to invade deeply and may involve the orbit early. Similarly, lateral canthal tumours have a tendency to involve the lateral conjunctival fornix and lateral orbit. BCCs recurring after radiotherapy are more difficult to diagnose because the tissue changes induced by radiation are very similar to those induced by the tumour. Therefore, these tumours present late and are more difficult to manage.12

Table 5. Poor prognostic factors for BCC.

| Aggressive histopathological subtype |

| Medial canthus |

| Lateral canthus |

| Large tumour |

| Indistinct borders |

| Recurrent or incompletely excised tumour |

| Previous radiotherapy |

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

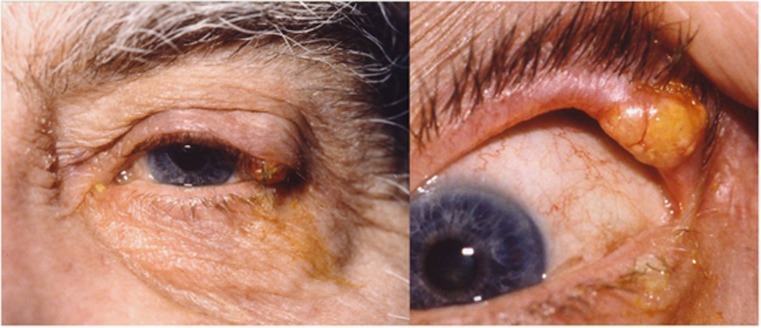

SCC (Figure 2) accounts for about 2–5% of malignant eyelid tumours.12 Like BCC, the lower lid is most frequently involved, UV light is implicated in its causation and the incidence peaks in fair-skinned patients in their seventh decade, with a slight male preponderance. They may derive from actinic keratosis or Bowen's disease and the risk increases after prolonged immunosuppression, previous radiotherapy and in patients with xeroderma pigmentosum. As SCCs arise from keratinocytes in the epidermis, hyperkeratosis or cutaneous horn formation are common features. Faustina et al18 found that the rate of metastasis to regional nodes could be as high as 24% with distant metastases and perineural invasion occurring less frequently. Poor prognostic factors include poorly differentiated tumours, large tumour size, and perineural invasion.

Figure 2.

SCC. (a) This ulcerating SCC at right medial canthus could be confused for a BCC because of the rolled edge. (b) A fleshy mass causing mechanical left lower lid ectropion and invading the orbit. (c) A large neglected SCC on the right upper lid causing mechanical ptosis. Note the hyperkeratosis on the surface.

Sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC)

This rare tumour, which arises from sebaceous glands, has a predilection for the head and neck, especially the meibomian glands in the upper lid.6, 7, 19 However, it can involve any of the sebaceous glands in the periocular area, including the caruncle. SGC is a very aggressive tumour, which metastasizes early and is often fatal. The incidence increases with age and peaks in the seventh to eighth decades.6, 7, 19 A recent retrospective review from a large US-based population registry confirmed that SGC accounted for a higher proportion of malignant skin tumours in Asian/Pacific Islander patients, but concluded that this is due to a relative lack of other skin tumours rather than an inherent risk of developing SGC in that subgroup compared with whites, as previously thought.19 The tumour may be multicentric and diffuse involvement of the eyelids and conjunctiva can occur because of pagetoid spread.6, 7, 12 It is renowned for masquerading as a wide variety of benign conditions, the commonest of which are a chalazion (Figure 3) or chronic blepharoconjunctivits.6, 7, 12 Other modes of presentation include a papilloma, trichiasis, conjunctival cicatrization, marginal keratitis, and corneal vascularization. Occasionally, it can also mimic other malignant pathology such as BCC and SCC.6 With such diverse presentation, SGC is often misdiagnosed and the diagnostic delay is responsible for significant morbidity and high mortality rate.6, 7, 12, 19 Therefore, one should maintain a high index of suspicion and a low threshold for full thickness eyelid biopsy in an elderly patient presenting with an atypical (solid) chalazion, a recurrent chalazion at the same site, chronic unilateral blepharitis or unilateral cicatrizing conjunctivitis. Conjunctival map biopsies should also be performed once the diagnosis is confirmed.

Figure 3.

SGC of the left upper lid masquerading as an atypical chalazion.

Malignant melanoma

Periocular melanoma is rare, accounting for <1% of all cutaneous melanomas.20 Lentigo maligna melanoma occurs more commonly than superficial spreading melanoma or nodular melanoma, and the lower lid is most often involved.20, 21 Exposure to UV light, including sun beds is an important risk factor for developing cutaneous melanoma.13, 14, 15, 22 They can arise de novo or from pre-existent lesions and are sometimes amelanotic. Breslow thickness and depth of tumour invasion (Clark's level) are important predictors of local, regional, and distant metastases, as well as overall survival. Tumours with Breslow thickness 1.5 mm or greater and/or Clarks level IV or greater are associated with increased mortality.23, 24

Non-surgical treatment of malignant periocular tumours

Although surgery remains the best treatment modality for managing malignant periocular tumours, less aggressive alternative treatments may be indicated if patients are unfit for surgery, refuse surgery, or have multiple lesions.1 The main non-surgical treatment modalities are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6. Non-surgical treatments for malignant periocular skin tumours.

| Radiotherapy |

| Cryotherapy |

| 5-FU |

| Imiquimod |

| PDT |

| Hedgehog signalling inhibitors |

Radiotherapy

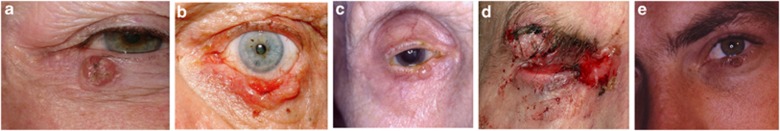

Radiotherapy achieves comparable cure rates to surgery for small malignant periocular tumours.1, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 The treatment is usually fractionated and the radiation dosage depends on the size and depth of the lesion. Radiotherapy is a good alternative to surgery in patients who are not fit for surgery. It has the obvious advantages of being painless, not requiring hospitalization and it is also useful for palliation, or as an adjunct to surgery in cases of incomplete tumour excision and/or perineural invasion. However, there are several disadvantages to radiotherapy. First, unlike surgery there is no histological evidence of tumour clearance. The recurrence rates after radiotherapy are higher than for surgery, especially for large tumours and sclerosing subtypes,25, 26, 28, 29, 31, 32 and when recurrence occurs it is usually difficult to diagnose, is fairly extensive and more difficult to manage.12 Further disadvantages include the risk of developing a second malignancy (Figure 4), radiation dermatitis, skin necrosis, skin depigmentation, madarosis, dry eye, cataract, conjunctival keratinization, and canalicular occlusion.

Figure 4.

SCC left upper lid with lacrimal gland involvement many years after radiotherapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Note the cutaneous changes because of radiation dermatitis.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy is a simple and effective means of treating malignant periocular tumours, achieving cure rates in excess of 90% with 5-year recurrence rates of 0–5% for small BCCs in several larger series.33, 34, 35 It is useful for treating patients who are unfit for surgery or have multiple lesions requiring treatment, for example, basal cell naevus syndrome. The tumour is frozen to −30 °C to induce cryodestruction, with either a cryoprobe or liquid nitrogen spray, using a double freeze–thaw technique and protecting the globe. The lacrimal apparatus is relatively resistant to cryotherapy, which can be used to treat lesions in close proximity to the punctum or canaliculus.12 Cryotherapy produces a profound tissue reaction resulting in swelling, erythema, blistering, and exudation of the periocular skin, which usually resolves within a fortnight; but permanent changes can occur, such as skin atrophy, notching of the lid margin, scarring, and lash loss.1

5-Fluorouracil

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) is an antimetabolite, which is widely used in dermatology for treating a variety of skin conditions, including actinic keratosis, and is approved for topical treatment of BCC.1 It functions by inhibiting DNA synthesis, causing tumour necrosis and preventing cell proliferation. The evidence supporting its use as monotherapy for BCC is weak and a recent systematic review concluded that more randomized controlled trials are required to assess the benefit of 5-FU for the treatment of BCC.36 As a result of high rates of adverse effects, dependence on patient compliance and relatively lower clearance rates compared with other treatment modalities, another systematic review recommended that its use should be limited to treating small tumours in low-risk locations, in patients who cannot undergo treatment with better-established therapies.37

Imiquimod

This immunomodulatory agent that induces cytokines and stimulates the immune response, has both antiviral and antitumour properties.38 It is approved for treating anogenital warts, superficial BCCs, and actinic keratosis, and is not approved for use in the periocular region, but in recent years there has been much interest in its use to treat a variety of other skin cancers, including lentigo maligna, other histological BCC subtypes, and SCC.39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 Data from large randomized clinical trials demonstrated imiquimod 5% cream to be statistically superior to placebo in treating superficial BCC45 but the clearance rates are inferior to surgery.39 Furthermore, no placebo-controlled, double-blind trials have evaluated the long-term sustained clearance of BCC after imiquimod therapy with histologic examination to document tumour eradication.45 Adverse effects often occur, including erythema, blistering, excoriation, burning, tenderness, and hypopigmentation.45, 46

Photodynamic therapy (PDT)

PDT relies on oxygen singlet free radicals, derived from a photochemical reaction between a photoactive molecule (photosensitizer) and light, to produce target cell injury and death.1, 39 BCC treatment is the most common oncologic application of PDT.39 The topical photosensitizers 5-ALA and the methylester of ALA are the agents most often used for the treatment of actinic keratosis and non-melanoma skin cancer. A variety of laser and non-laser light sources are used in PDT, and blue (430 nm) and red (630 nm) light sources are most commonly employed. The main limitation of current light sources is depth of penetration into the skin.47 There are very few studies comparing the efficacy of PDT with standard treatment modalities, such as surgery. Although modest short-term cure rates have been reported,48, 49, 50 long-term recurrence rates are higher51, 52 and the efficacy of PDT in the long term is yet to be established.36, 39

Hedgehog signalling inhibitors

The hedgehog (Hh) signalling pathway is a key regulator of cell growth and differentiation during development, and a link exists between the Hh pathway signalling activation and several human cancers, including BCC.53, 54 The PTCH1 gene on 9q22 has a tumour-suppressor role and loss-of-function mutations of human PTCH1 on human chromosome 9q22 are associated with basal cell naevus syndrome (Gorlin syndrome).55, 56 Vismodegib is an inhibitor of smoothened, a key component of the Hh pathway.54, 57, 58 It has shown promising antitumour activity and is the first licensed Hh signalling inhibitor in clinical use for treating locally advanced and metastatic BCC.

Surgery

Surgery remains the main treatment modality for management of periocular cancer. Unlike other treatment modalities, it allows histological confirmation of the diagnosis. Furthermore, examination of the excision margin assesses the adequacy of tumour clearance.

Tumour clearance

In order to minimize the risk of incomplete excision, conventional surgery for periocular skin cancer usually involves a wide margin, which is fairly arbitrary, and varies with tumour type.59, 60 Most surgeons allow 3–4 mm for BCC, 4–6 mm for SCC, and 5–6 mm for SGC, lentigo maligna and in situ melanoma. For thin melanomas, 5–6 mm may be adequate but it is prudent to allow 10 mm for tumours with Breslow thickness 2 mm or greater.24 For thick melanomas and/or depth of invasion beyond Clark's level IV, sentinel node biopsy and lymph node dissection may help to reduce regional lymph node recurrence.

Confirmation of tumour clearance is essential before undertaking periocular reconstruction. Routine paraffin-fixed specimens take several days to be processed, but the specimens can be processed within 24–48 h by prior arrangement with the local pathologist, allowing delayed reconstruction. Margin control can also be achieved by the use of frozen section, but there are inherent inaccuracies in frozen-section techniques, and it is not unusual for frozen sections to be clear with involved margins on paraffin-fixed specimens.

Unlike the vertical sections used to assess paraffin-fixed and frozen-section specimens, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) involves removal of the tumour and serial flattened sections from the edge and the base of the defect. Each resected layer is mapped with coloured inks, processed using thin frozen sections, and examined microscopically. The position of any residual tumour is identified and the process is repeated. Frederick Mohs first developed the technique of in situ chemo-fixation, using zinc chloride in experimental animals in the 1930s and published his first study of chemosurgery in humans in 1941.61 Owing to limitations of chemosurgery in the periorbital region, the technique was superseded by the frozen-section modification widely employed today.

As it allows three-dimensional assessment of the tumour margins MMS has excellent cure rates for non-melanoma skin cancers and is widely regarded as the gold standard for tumour excision.62, 63, 64 Mohs himself reported 5-year cure rates of 99.4% for 1124 primary BCC and 92.4% for 290 recurrent BCC.65 Our own experience in Cambridge confirms a low recurrence rate after MMS for primary BCCs (1.3–1.6%) but the recurrence rates for recurrent or incompletely excised BCCs (13–20%) are even higher than other published series, highlighting the fact that the first attempt at tumour extirpation gives the best chance of long-term cure.66 The ‘slow Mohs' modification of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections also gives excellent cure rates for BCC67 and mapped serial excision is a very useful method of achieving margin control for periocular melanoma.68 MMS is highly recommended for medial canthal BCCs, which tend to invade deeply, for high-risk tumour subtypes, where tumour margins are indistinct, and for recurrent tumours. Precise tissue mapping also allows conservation of normal healthy tissue, which is a great advantage in the periocular area, where critical structures exist and where reconstructive surgery can be challenging. Critics of MMS claim that it is time consuming, involves at least two specialists and is expensive. However, when the advantages of MMS are taken into account it is probably cost-effective compared with traditional surgery.69, 70 The main disadvantage of MMS is that it is not widely available. Traditional MMS also suffers from the inherent inaccuracies of frozen-section techniques.

Orbital invasion by periocular malignancies

Orbital invasion by periocular tumours occurs rarely. Although it is often silent, orbital invasion should be suspected if a patient with a current or previously treated periocular malignancy presents with a palpable orbital mass, globe displacement, limitation of eye movement, numbness, or pain in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.71, 72 BCCs are most commonly implicated; often incompletely excised or recurrent tumours, with aggressive histopathology and medial canthal location.71, 73 Local tumour clearance is usually possible by orbital exenteration with or without adjunctive radiotherapy. However, perineural invasion occurs commonly in such cases, and increases the risk of incomplete excision even after exenteration.71 Furthermore, perineural invasion worsens the prognosis because of extensive orbital, and sometimes intracranial, involvement.

Eyelid reconstruction

The defects that result from periocular tumour excision can be surprisingly large, especially after margin controlled excision, and present special challenges for the reconstructive surgeon. The aims of eyelid reconstruction are to restore the integrity of the eyelid, protect the ocular surface, and produce a good cosmetic result. A detailed account of eyelid reconstruction is beyond the scope of this article and only general principles will be discussed briefly.

The eyelid basically comprises an anterior lamella (skin and orbicularis) and a posterior lamella (tarsus and conjunctiva). Support for the eyelids is provided by the medial and lateral canthal tendons. Small eyelid defects may be closed directly or left to heal by secondary intention. Reconstruction of larger eyelid defects usually requires reconstruction of the constituent lamellae either with a skin flap or skin graft (Figure 5). At least one lamella should have a blood supply and the reconstructed eyelid should have adequate support, otherwise eyelid malposition or canthal dystopia will result. By paying attention to the basic principles good results can be achieved.

Figure 5.

Pre-operative, per-operative, and post-operative appearance of a large ulcerating BCC on the upper lid. The resultant defect was repaired with a supraclavicular skin graft.

There is a wide variety of local skin flaps used for anterior lamellar reconstruction.12, 74 Generally speaking skin flaps are preferable to skin grafts because they possess a blood supply, contract less, provide a better colour and texture match, do not involve violation of a distant donor site and their thickness can be varied depending on the depth of the defect. Full thickness skin grafts are used more commonly than split thickness skin grafts, which tend to contract and give a poor colour match. The commonest sites for harvesting full thickness skin grafts are upper lid, pre-auricular area, post-auricular area, supraclavicular fossa, and iliac fossa. Posterior lamellar reconstruction should ideally provide a smooth mucosal surface to line the eyelid. Like the anterior lamella, there are many options for posterior lamellar reconstruction, including free grafts and vascularized flaps (Table 7). Medial and/or lateral periosteal flaps may be required to provide support for the reconstructed eyelid.

Table 7. Tissues used for posterior lamellar reconstruction.

| Tarsoconjunctival flap |

| Hughes |

| Hewes |

| Tarsoconjunctival graft |

| Tarsomarginal graft |

| Buccal mucosa |

| Hard palate |

| Nasal septum (cartilage and mucosa) |

| Pericranial flap |

| Donor sclera |

| Auricular cartilage |

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Murchison AP, Walrath JD, Washington CV. Non-surgical treatments of primary, non-melanoma eyelid malignancies: a review. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2011;39:65–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BE, Bartley GB. Epidemiological characteristics and clinical course of patients with eyelid tumors in an incidence cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmol. 1999;106:746–750. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domonkos AN. Treatment of eyelid carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1965;91:364–370. doi: 10.1001/archderm.91.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C.A benign or malignant eyelid lump - can you tell? An unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma BMJ Case Repe-pub ahead of print June 2012;doi: 10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Buckel TB, Helm KF, Ioffreda MD. Cystic basal cell carcinoma or hidrocystoma? The use of an excisional biopsy in a histopathologically challenging case. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:67–69. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200402000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields JA, Demirci H, Marr BP, Eagle RC, Shields CL. Sebaceous carcinoma of the ocular region: a review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50:103–122. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher M, Hintschich C, Garner A, Bunce C, Collin JRO. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathological study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1049–1055. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.9.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitskaya E, Rene C, Dean A.Spontaneous haemorrhage in an eyelid hidrocystoma in a patient treated with clopidogrel Eye (Lond)in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rice JC, Zaragoza P, Waheed K, Schofield J, Jones CA. Efficacy of incisional vs punch biopsy in the histological diagnosis of periocular skin tumours. Eye (Lond) 2003;17:478–481. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro RC, de Macedo EM, de Lima PP, Bonatti R, Matayoshi S. Is 2-mm punch biopsy useful in the diagnosis of malignant eyelid tumors. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28:282–285. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31825a65b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Moore S, Kumar B. Punch biopsy in the management of periocular basal cell carcinomas. Orbit. 2004;23 (2:87–92. doi: 10.1080/01676830490501497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherbarrow B.Oculoplastic Surgery2nd ed.Informa Healthcare: London; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Leiter U, Garbe C. Epidemiology of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer--the role of sunlight. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;624:89–103. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77574-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DR, Armstrong BK, Kricker A, Fleming C. Sunlight and cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:271–283. doi: 10.1023/a:1018440801577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doré JF, Chignol MC. Tanning salons and skin cancer. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2012;11:30–37. doi: 10.1039/c1pp05186e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehner MR, Shive ML, Chren MM, Han J, Qureshi AA, Linos E. Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e5909. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. Study of a series of 1039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:1118–1126. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70344-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustina M, Diba R, Ahmadi MA, Esmaeli B. Patterns of regional and distant metastasis in patients with eyelid and periocular squamous cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1930–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta T, Wilson L, Yu J. A retrospective review of 1349 cases of sebaceous carcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115:158–165. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri M, Buffam FV, Martinka M, Oryschak A, Dhaliwal H, White VA. Clinicopathologic features and behavior of cutaneous eyelid melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:901–908. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)00962-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan FM, O'Donnell BA, Whitehead K, Ryman W, Sullivan TJ. Treatment and outcomes of malignant melanoma of the eyelid: a review of 29 cases in Australia. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boniol M, Autier P, Boyle P, Gandini S. Cutaneous melanoma attributable to sunbed use: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e4757. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeli B, Wang B, Deavers M, Gillenwater A, Goepfert H, Diaz E, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in malignant melanoma of the eyelid skin. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;16:250–257. doi: 10.1097/00002341-200007000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeli B, Youssef A, Naderi A, Ahmadi MA, Meyer DR, McNab A. Margins of excision for cutaneous melanoma of the eyelid skin: the Collaborative Eyelid Skin Melanoma Group Report. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;19:96–101. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000056141.97930.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagrodnik B, Kempf W, Seifert B, Müller B, Burg G, Urosevic M, et al. Superficial radiotherapy for patients with basal cell carcinoma: recurrence rates, histologic subtypes, and expression of p53 and Bcl-2. Cancer. 2003;98:2708–2714. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshin B, Yeatts P, Anscher M, Montano G, Dutton JJ. Management of periocular basal cell carcinoma: Mohs' micrographic surgery versus radiotherapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;38:193–212. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(93)90101-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haye C, Vilcoq JR. External radiotherapy for carcinoma of the eyelid: report of 850 cases treated. Int JRadiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;34:277–287. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)02135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick PJ, Thompson GA, Easterbrook WM, Gallie BL, Payne DG. Basal and squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelids and their treatment by radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1984;10:449–454. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(84)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederman M. Radiation treatment of cancer of the eyelids. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976;60:794–805. doi: 10.1136/bjo.60.12.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen K, Gadeberg C. Carcinoma of the eyelid. Acta Radiol Oncol Radiat Phys Biol. 1978;17:58–64. doi: 10.3109/02841867809127691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Gladstein AH, Bart RS, Grin CM, Levenstein MJ. Recurrence rates of treated basal cell carcinomas. Part 4: X-ray therapy. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:549–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb03508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avril MF, Auperin A, Margulis A, Gerbaulet A, Duvillard P, Benhamou E, et al. Basal cell carcinoma of the face: surgery or radiotherapy? Results of a randomized study. Br J Cancer. 1997;76:100–106. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren G, Larko O. Long-term follow-up of cryosurgery of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:742–746. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann W. A reappraisal of cryosurgery for eyelid basal cell carcinomas. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:453–457. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.4.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro L, Price E. Cryosurgical management of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid: a 10-year experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:316–317. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormerod A, Rajpara S, Craig F. Basal cell carcinoma. Clin Evid (Online) 2010;4:1719. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love WE, Bernhard JD, Bordeaux JS. Topical imiquimod or fluorouracil therapy for basal and squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1431–1438. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauder DN. Immunomodulatory and pharmacologic properties of imiquimod. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:S6–11. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.107808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lien MH, Sondak VK. Nonsurgical treatment options for basal cell carcinoma. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:571734. doi: 10.1155/2011/571734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal D, Matías-Guiu X, Alomar A. Fifty-five basal cell carcinomas treated with topical imiquimod: outcome at 5-year follow-up. Arch Dermato. 2007;143:266–268. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AH, Kennedy CT, Collins C, Harrad RA. The use of imiquimod in the treatment of periocular tumours. Orbit. 2010;29:83–87. doi: 10.3109/01676830903294909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiessl C, Wolber C, Tauber M, Offner F, Strohal R. Treatment of all basal cell carcinoma variants including large and high-risk lesions with 5% imiquimod cream: histological and clinical changes, outcome, and follow-up. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:507–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman DK, Carroll MT. Topical imiquimod therapy for basal and squamous cell carcinomas: a clinical experience. Cutis. 2007;79:241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci H, Shields CL, Bianciotto CG, Shields JA. Topical imiquimod for periocular lentigo maligna. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:2424–2429. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karve SJ, Feldman SR, Yentzer BA, Pearce DJ, Balkrishnan R. Imiquimod: a review of basal cell carcinoma treatments. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:1044–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon Y, Brodell RT. Local reactions to imiquimod in the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancaleon L, Moseley H. Laser and non-laser light sources for photodynamic therapy. Lasers Med Sci. 2002;17:173–186. doi: 10.1007/s101030200027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley P, Freeman M, Menter A, Siller G, El-Azhary RA, Gebauer K, et al. Photodynamic therapy with methyl aminolevulinate for primary nodular basal cell carcinoma: results of two randomized studies. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1236–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.04022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surrenti T, De Angelis L, Di Cesare A, Fargnoli MC, Peris K. Efficacy of photodynamic therapy with methyl aminolevulinate in the treatment of superficial and nodular basal cell carcinoma: an open-label trial. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:412–415. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes LE, de Rie M, Enström Y, Groves R, Morken T, Goulden V, et al. Photodynamic therapy using topical methyl aminolevulinate vs surgery for nodular basal cell carcinoma: results of a multicenter randomized prospective trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:17–23. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza CS, Felicio LB, Ferreira J, Kurachi C, Bentley MV, Tedesco AC, et al. Long-term follow-up of topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy diode laser single session for non-melanoma skin cancer. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2009;6:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink-Puches R, Soyer HP, Hofer A, Kerl H, Wolf P. Long-term follow-up and histological changes of superficial nonmelanoma skin cancers treated with topical delta-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:821–826. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Chi S, Xie J. Hedgehog signaling in skin cancers. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1235–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, Reddy JC, Tibes R, Weiss GJ, Borad MJ, et al. Phase I trial of hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib (GDC-0449) in patients with refractory, locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2502–2511. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn H, Wicking C, Zaphiropoulous PG, Gailani MR, Shanley S, Chidambaram A, et al. Mutations of the human homolog of drosophila patched in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Cell. 1996;85:841–851. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Rothman AL, Xie J, Goodrich LV, Bare JW, Bonifas JM, et al. Human homolog of patched, a candidate gene for the basal cell nevus syndrome. Science. 1996;272:1668–1671. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating GM. Vismodegib: in locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma. Drugs. 2012;72:1535–1541. doi: 10.2165/11209590-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, Dirix L, Lewis KD, Hainsworth JD, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171–2179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abide JM, Nahai F, Bennett RG. The meaning of surgical margins. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:492–497. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198403000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein MC, Brodell RT, Bordeaux J, Honda K. The art and science of surgical margins for the dermatopathologist. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:737–745. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31823347cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohs FE. Chemosurgery: a microscopically controlled method of cancer excision. Arch Surg. 1941;42:279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra R, Huilgol SC, Huynh NT, Selva D. The Australian Mohs database, part I: periocular basal cell carcinoma experience over 7 years. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:624–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra R, Huilgol SC, Huynh NT, Selva D. The Australian Mohs database, part II: periocular basal cell carcinoma outcome at 5-year follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:631–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra R, Huilgol SC, Huynh NT, Selva D. The Australian Mohs database: periocular squamous cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohs FE. Micrographic surgery for the microscopically controlled excision of eyelid cancers. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:901–909. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050180135046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin AS, Rytina E, Ha T, René C, Woodruff SA.Management of periocular basal cell carcinoma by Mohs micrographic surgery J Dermatolog Treat 2012. e-pub ahead of print 10 July 2012; doi: 10.3109/09546634.2012.690506 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morris DS, Elzaridi E, Clarke L, Dickinson AJ, Lawrence CM. Periocular basal cell carcinoma: 5-year outcome following Slow Mohs surgery with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections and delayed closure. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:474–476. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.141325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huilgol SC, Selva D, Chen C, Hill DC, James CL, Gramp A, et al. Surgical margins for lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma: the technique of mapped serial excision. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1087–1092. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.9.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes EA, Dickinson AJ, Langtry JA, Lawrence CM. The role of Mohs excision in periocular basal cell carcinoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:660–661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J, Zitelli JA. Mohs micrographic surgery: a cost analysis. Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:698–703. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibovitch I, McNab A, Sullivan T, Davis G, Selva D. Orbital invasion by periocular basal cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyers AG. Orbital exenteration for invasive skin tumours. Eye. 2006;20:1165–1170. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuliano A, Strianese D, Uccello G, Diplomatico A, Tebaldi S, Bonavolontà G. Risk factors for orbital exenteration in periocular basal cell carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:238–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyers AG, Collin JRO.Colour atlas of ophthalmic plastic surgery2nd edn.Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford; 2001 [Google Scholar]