Abstract

The tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) classification is a universal cancer staging system, which has been used for five decades. The current seventh edition became effective in 2010 and covers six ophthalmic sites: eyelids, conjunctiva, uvea, retina, orbit, and lacrimal gland; and five cancer types: carcinoma, sarcoma, melanoma, retinoblastoma, and lymphoma. The TNM categories are based on the anatomic extent of the primary tumour (T), regional lymph node metastases (N), and systemic metastases (M). The T categories of ophthalmic cancers are based on the size of the primary tumour and any invasion of periocular structures. The anatomic category is used to determine the TNM stage that correlates with survival. Such staging is currently implemented only for carcinoma of the eyelid and melanoma of the uvea. The classification of ciliary body and choroidal melanoma is the only one based on clinical evidence so far: a database of 7369 patients analysed by the European Ophthalmic Oncology Group. It spans a prognosis from 96% 5-year survival for stage I to 97% 5-year mortality for stage IV. The most accurate criterion for prognostication in uveal melanoma is, however, analysis of chromosomal alterations and gene expression. When such data are available, the TNM stage may be used for further stratification. Prognosis in retinoblastoma is frequently assigned by using an international classification, which predicts conservation of the eye and vision, and an international staging separate from the TNM system, which predicts survival. The TNM cancer staging manual is a useful tool for all ophthalmologists managing eye cancer.

Keywords: conjunctival malignancies, eyelid malignancies, orbital malignances, retinoblastoma, uveal melanoma

The tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) classification is a cancer staging system, which has been in worldwide use across all medical specialties for five decades.1 It emerged in 1968 when the International Union Against Cancer published the first edition of its classification based on the anatomic extent of the tumour after testing a set of draft classifications for 23 cancer sites. None of these sites related to the eye.

Indeed, eye cancer is a latecomer in the TNM classification, appearing for the first time in the fourth and fifth editions.2 The first ophthalmic section covered six sites and five cancer types—carcinoma and melanoma of the eyelid and conjunctiva, melanoma of the uvea, retinoblastoma, sarcoma of the orbit, and carcinoma of the lacrimal gland—but these classifications were untested and were rarely used outside cancer registries.

The ophthalmic section was revised for the sixth edition of TNM in 2002.3 This edition was based on the published literature, but the classifications were not tested against clinical data. The revision received publicity4 but did not make a breakthrough. Meanwhile, data were collected of other cancers to improve staging. For the updated TNM classification of cutaneous melanoma, data from over 20 000 patients eventually were analysed to create a system that best separated patients according to survival.5

When drafting of the current seventh edition of TNM commenced, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) appointed an International Ophthalmic Oncology Task Force and charged it with writing a revision based on published and acquired evidence.6 The ophthalmic section became the most extensively edited one. Among other improvements, it added a chapter on adnexal lymphoma7 and based the classification of uveal melanoma on a large collaborative database.8 The thoroughly revised seventh TNM edition is a useful tool for every ophthalmologist managing eye cancer.6

The first step: anatomic TNM categories

The TNM system is based on the anatomic extent of the tumour as determined clinically and, in most instances, histopathologically.1, 9 A notable exception is uveal melanoma, because this tumour is mostly treated non-surgically. This principle reflects a desire to have a basic concept that is applicable to all cancer sites, irrespective of the selected treatment. Although the anatomic extent has lost some of its significance as an indicator of prognosis, it remains crucial in the planning of treatment and evaluation of outcomes.

The T categories refer to the primary tumour and always number four (T1–T4). They may have subcategories indicated with a small letter postfix (eg, T1a). Non-invasive in situ tumours can be indicated with Tis. The N categories refer to regional lymph node metastases: N0 indicates none, whereas N1 (or, in specific sites, a higher N category) denotes regional metastasis. The M categories refer to systemic metastasis: M0 and M1 indicate absence and presence of dissemination, respectively. No higher M categories are used, but subcategories indicated with postfixes can be added.

Ideally, every tumour would be confirmed by histopathology to yield an updated pTNM category. If the classification is based on clinical data, the prefix c can be added for clarity (eg, cT1N0M0). The TNM system also has extensions, which allow, for example, recording of multiple, residual, and recurrent tumours.

The second step: TNM stages

In addition to anatomic tumour categories, most sites and tumour types also have a TNM staging system.1, 9 The stage is assigned only once the anatomic extent of the tumour has been determined. Each stage aims to be homogeneous with respect to survival probability and as different from other stages as possible. Stages I to III correspond to progressively higher mortality from localised and regional cancer. Stage IV is equivalent to systemic metastases. Each stage can be expanded with subcategories, this time with capital letter postfixes (eg, IIA).

If a staging system is implemented, survival should be analysed according to TNM stages rather than the underlying anatomic categories, which are less likely to correlate with prognosis, especially when expanded with subcategories. This is a concept that neophytes to using TNM quite often miss.

Ophthalmic sites in the current TNM classification

The current, seventh edition of the TNM maintains the original six ophthalmic sites: eyelids, conjunctiva, uvea, retina, orbit, and lacrimal gland, and four cancer types, carcinoma, melanoma, retinoblastoma, and lymphoma (Table 1).9 The chapter on ocular adnexal lymphoma covers three of these sites.7 A staging system is implemented for carcinoma of the eyelid and melanoma of the uvea.

Table 1. Overview of ophthalmic sites in the current, seventh edition of the TNM classification9.

| Site | Cancer type |

Number of anatomic categories |

Staging system | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | N | M | |||

| Eyelid | Carcinoma | 6 | 2 | 2 | Available |

| Conjunctiva | Carcinoma | 9 | 2 | 2 | None |

| Conjunctiva | Melanoma | 14 | 2 | 2 | None |

| Uvea | Melanoma | 17 | 2 | 4 | Available |

| Retina | Retinoblastoma | 11 | 3 | 6 | None |

| Orbit | Lacrimal carcinoma | 6 | 2 | 2 | None |

| Orbit | Sarcoma | 4 | 2 | 2 | None |

| Multisite | Adnexal lymphoma | 12 | 5 | 4 | None |

Abbreviation: TNM, tumour, node, metastasis.

Carcinoma and sarcoma of the eyelids, conjunctiva, lacrimal gland, and orbit

The three classifications for periocular carcinoma (Figures 1a and b)10, 11 and the one for orbital sarcoma are based on the size of the primary tumour and invasion of adjacent structures (Table 2).9 They have yet to be validated by clinical studies.

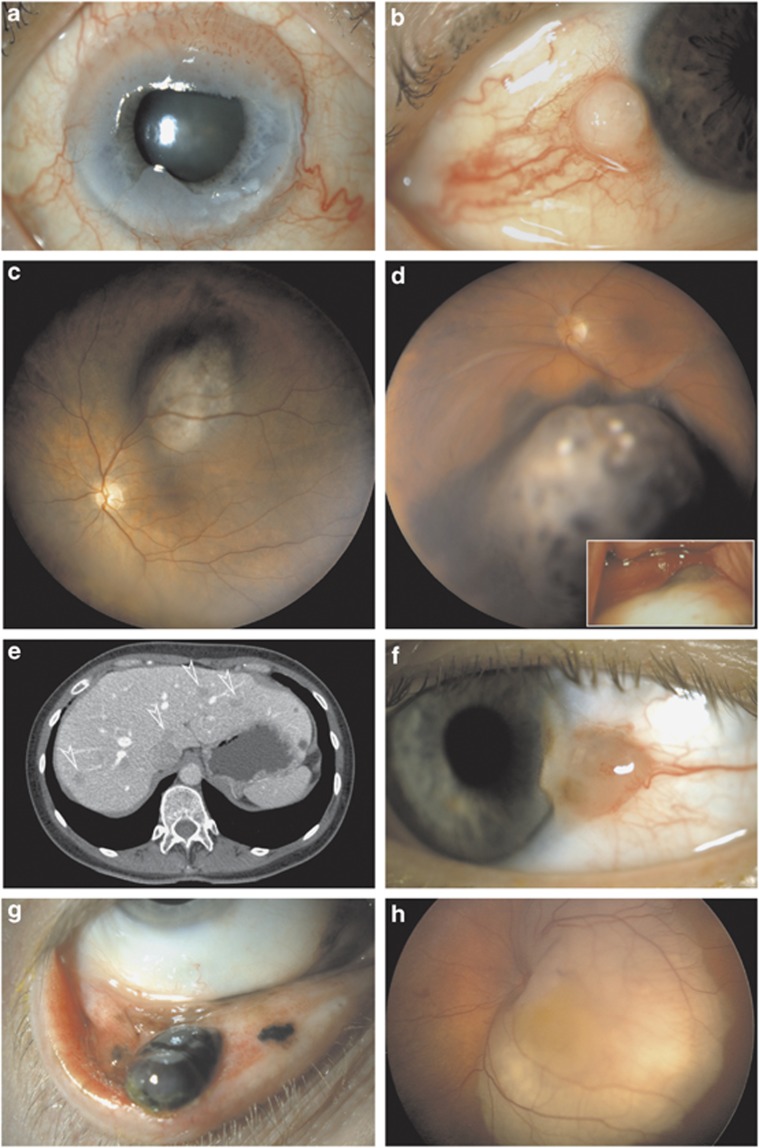

Figure 1.

Examples of TNM classification and staging of eye cancer with treatment and outcome. (a) Circumlimbal conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasm in an 84-year-old woman: Tis, topical fluorouracil, no recurrence at 8 years. (b) Perilimbal conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma 4.5 mm in diameter in a 75-year-old man: pT2N0M0, surgical excision, adjuvant topical fluorouracil, and no recurrence at 3 years. (c) Perifoveal choroidal melanoma 3.3 mm in thickness and 9.1 mm in largest diameter in a 50-year-old woman: T1aN0M0, ruthenium brachytherapy, and no recurrence at 7 years. (d) Choroidal and ciliary body melanoma 5.9 mm in thickness and 14.9 mm in diameter by histopathology with a 4-mm extraocular extension (inset) in a 54-year-old man: pT2dN0M0, stage IIIA, spindle cell type, enucleated recently, and postoperative adjuvant external beam radiotherapy. (e) Multiple hepatic metastases (arrowheads) from choroidal melanoma confirmed by needle biopsy in a 47-year-old woman, largest diameter of largest metastasis 16 mm: M1a and HUCH Working Formulation stage IVa, systemic chemotherapy, and survival 19 months. (f) Limbal conjunctival melanoma, 1.5 mm thick, in a 46-year-old man: pT1bN0M0, excision with adjuvant topical mitomysin, sentinel node biopsy not indicated, and no recurrence in 2 years. (g) Multifocal palpebral conjunctival melanoma, largest focus 3.5 mm thick, in a 60-year-old man: pT2cN0M0, resection, amniotic membrane reconstruction, sentinel node biopsy and adjuvant topical mitomycin, nodes negative, and no recurrence in 4 years. (h) Left eye of a 10-month-old girl with trilateral retinoblastoma, thickness 7.2 mm and largest diameter 16.5 mm, and no seeding: this eye T1bN0M0, group B in International Classification, managed with systemic chemotherapy and transpupillary thermotherapy, and no recurrence at 5 years.

Table 2. Overview of the classification of periocular carcinomas and orbital sarcoma in the seventh edition of the TNM classification9.

| Anatomic category |

Carcinoma |

Sarcoma |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eyelids | Conjunctivaa | Lacrimal glanda | Orbita | |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ (stage 0) | Carcinoma in situ | — | — |

| T1 | Size ≤5 mm, does not invade the tarsus or eyelid margin (stage IA) | Size ≤5 mm | Size ≤20 mm, with or without extension to the orbital soft tissue | Size ≤15 mm |

| T2 | Size >5–10 mm or invades the tarsus or eyelid margin (T2a, stage IB); size >10–20 mm or involves full thickness of the eyelid (T2b, stage IC) | Size >5 mm, does not invade adjacent structures | Size >20–40 mm | Size >15 mm, does not invade eyeglobe or bone |

| T3 | Size >20 mm or invades the adjacent structures or perineurally (T3a, stage II); complete resection requires enucleation, exenteration, or bone resection (T3b, stage IIIA) | Invades adjacent structures but not the orbit | Size >40 mm | Invades orbital tissues or bone |

| T4 | Not resectable (stage IIIC) | Invades the orbit or beyond | Invades periosteum (T4a), bone (T4b), or adjacent structures (T4c, eg, sinuses) | Invades the eyeglobe or periorbital structures (eg, eyelids) |

| N1 | Any T, M0 (stage IIIB) | |||

| M1 | Any T, any N (stage IV) | |||

Abbreviation: TNM, tumour, node, metastasis.

No staging system is implemented.

Uveal melanoma

Depending on the centre, the selected treatment and the preferences of the managing ophthalmologist and patient, prognostication of uveal melanoma may be based on clinical findings alone or also on histopathological and genetic features.12

Prognosis of the primary tumour

Clinical prognostication

The TNM classification of ciliary body and choroidal melanoma is based on a collaborative analysis by the European Ophthalmic Oncology Group, which included baseline and survival data of 7369 patients, randomly divided into a building and a validation data set.8 The classification of iris melanoma13 was not revised because of insufficient data. Uveal melanoma metastasises haematogenously unless it invades the conjunctiva, in which case it can spread to regional lymph nodes, albeit extremely rarely. The classification is consequently based on the extent of the primary tumour and on the presence of any systemic metastases.9

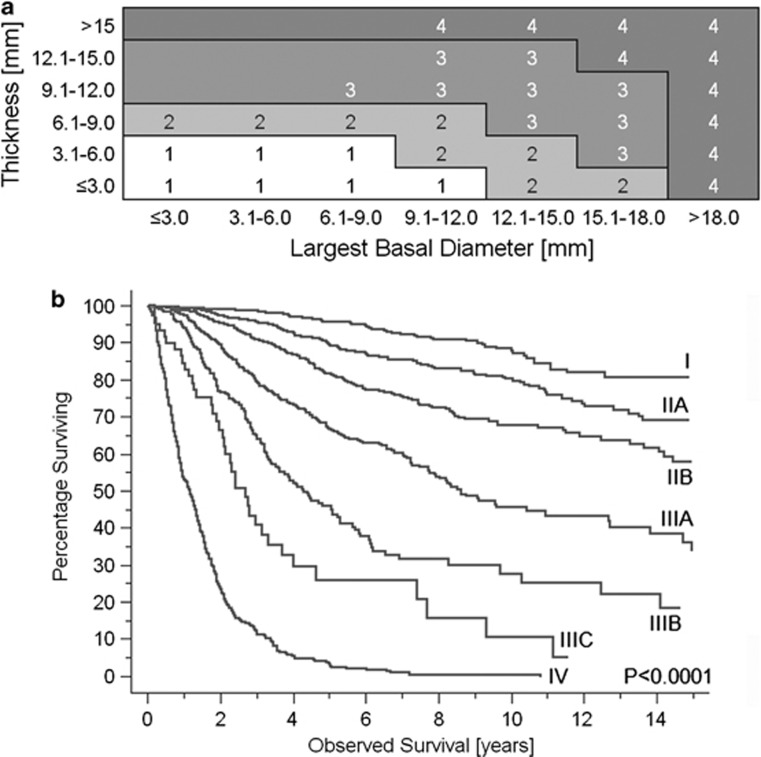

The T category is based on tumour size (Figures 1c and d). The appropriate size category corresponding to small (T1), medium-sized (T2), large (T3), or very large (T4, a new category) melanoma is read from a table composed of 3 × 3 mm2 blocks of tumour thickness and largest basal diameter (Figure 2a). The blocks have been grouped according to survival probability. One of five subcategories (a–e) is determined according to the presence or absence of ciliary body and extraocular extension (Table 3). Extraocular extension is further categorised based on its size (Figure 1d).

Figure 2.

(a) Size boundaries of T categories defined empirically by dividing data of 7369 patients with a chroidal and ciliary body melanoma of known largest tumour basal diameter and thickness into blocks representing 3 × 3 mm fractions and then combining blocks with similar survival. Numbers within blocks are T categories. (b) Kaplan–Meier survival curves displaying melanoma-related mortality for 5403 patients with known tumour size, ciliary body, and extraocular extension (stage I–IIIC), and for 224 patients with newly detected metastatic uveal melanoma (stage IV).

Table 3. Overview of the classification of malignant ciliary body and choroidal melanoma in the seventh edition of the TNM classification9.

| Size category, see Figure 1a |

Tumour extension outside the choroid |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Ciliary body only | Extraocular only, ≤5 mm | Ciliary body and extraocular ≤5 mm | Any extraocular >5 mm | |

| T1 | T1a (stage I) | T1b (stage IIA) | T1c (stage IIA) | T1d (stage IIA) | |

| T2 | T2a (stage IIA) | T2b (stage IIB) | T2c (stage IIIA) | T2d (stage IIIA) | |

| T3 | T3a (stage IIB) | T3b (stage IIIA) | T3c (stage IIIA) | T3d (stage IIIB) | |

| T4 | T4a (stage IIIA) | T4b (stage IIIB) | T4c (stage IIIB) | T4d (stage IIIC) | T4e (stage IIIC) |

Abbreviation: TNM, tumour, node, metastasis.

Clinical and pathological classifications are identical; if N1 or M1, the stage is IV regardless of size category.

The evidence-based revision of the anatomic classification made the size categories more equally sized than what they were in previous editions. Notably, tumour thickness in the group of small (T1) tumours can now be up to 6 mm instead of 2.5–3.0 mm in the previous editions, provided that largest basal diameter of the tumour does not exceed 9.0 mm (Figure 1c). Nevertheless, the 10-year Kaplan–Meier estimate of survival for T1 melanomas is 89%.8 The new edition also makes more efficient use of ciliary body and extraocular extension than what was the case with previous editions.14

Staging for uveal melanoma has been implemented.9 The 17 anatomic categories are rearranged into six stage categories and subcategories I, IIA–B, and IIIA–C (Table 3). A seventh category, stage IV, corresponds to systemic metastases as mentioned. Each stage includes anatomic categories that have the most similar prognosis. The stages span prognosis from 96% 5-year survival for stage I to 97% 5-year mortality for stage IV (Figure 2b).8

Histopathological prognostication

The time-honoured histopathological feature associated with prognosis of uveal melanoma is its cell type.15 Although a strong prognostic indicator, ophthalmic pathologists are notoriously discordant in assigning cell type, and over time the categories used have collapsed from five to three. Today, some ophthalmic pathologists simply divide tumours into those with or without epithelioid cells, the former having a worse prognosis.

Cell type is the only histopathological feature that the TNM system uses for grading uveal melanomas.9 It has retained the division into spindle, epithelioid, and mixed-cell-type melanomas (the latter is defined as having more than 10% of the less abundant cell type). However, the TNM system now encourages recording of additional histopathological data, which might be used in future editions. These include the mitotic count,16 the mean diameter of the 10 largest nucleoli,17, 18 extravascular matrix patterns,19, 20 and microvascular density.21, 22, 23

Genetic prognostication

Genetic analysis provides the single best estimate for the risk of metastasis from uveal melanoma.12, 24, 25 Such an analysis can be performed by charting chromosomal alternations26, 27 or by gene expression profiling.24, 25, 28 The latest TNM edition encourages recording of genetic features.9

A major breakthrough was the observation that many uveal melanomas lack one copy of chromosome 3, and that these monosomic tumours are usually those that metastatise.29, 30 Simple determination of monosomy 3 is inaccurate, however, because the chromosomal defect can be masked by: (1) duplication of the remaining copy to produce isodisomy (both chromosomes then derive from the same parent); (2) partial chromosomal deletion, which can be missed by some methods; and (3) modulation of the risk of metastasis by other choromsomal errors, such as 6p gain and 8q gain.31, 32, 33 At present, the method of choice for initial chromosomal analysis is multiple ligation probe amplification (MLPA), which probes multiple loci across several chromosomes.31, 32, 33, 34 If the result contradicts the histopathological grade, reanalysis with methods such as complete genomic hybridization is advisable.31, 33 Advantages of MLPA include low cost and data obtained simultaneously from several chromosomes other than chromosome 3. A disadvantage is that the technique needs to be validated individually for each laboratory. Currently, MLPA as a service is available from the Liverpool Ocular Oncology Centre (Liverpool, UK).

Gene expression profiling aims to divide uveal melanomas into two types, class 1, which does not metastasise or does so only rarely, and class 2, which typically metastasises.24, 25 The profiling is based on the analysis of tumour RNA, and unlike chromosomal alterations, which can vary within a tumour, the expression profile is claimed to be uniform throughout the tumour. Gene expression profiling is available as a commercial, internally validated service from Castle Biosciences Inc. (Friendswood, TX, USA). An advantage of this technique is that it needs a smaller amount of tumour tissue than MLPA.35, 36 A disadvantage is its relatively high price. The commercial profiling was recently revalidated through a prospective, collaborative study of 446 patients, in which 3 of 47 metastases developed from class 1 melanomas,36 suggesting a need for refining the classification.

Analysis of very long-term survival data show that metastases of uveal melanoma can remain occult for three decades after enucleation of the primary tumour.37 Metastatic disease remains the single leading cause of death over time. Statistical evidence is not sufficient ever to reassure patients with confidence that they are cured.37 Does this mean that all patients with a class 2 uveal melanoma, or an equivalent MLPA profile, ultimately die of metastases? In the data set used to construct the current TNM classification, the Kaplan–Meier estimates of 15-year mortality from metastatic melanoma were 19, 31, 42, 66, and 82% for stages I–IIIB, respectively.8 The corresponding percentages of tumours assigned to class 2, calculated from the T categories published in the prospective validation study,36 are 19, 31, 41, 52 and 82%. These two series of figures are indeed very similar.

Prognosis after dissemination

Several retrospective multivariate analyses of metastatic uveal melanoma have been published. The first study proposing staging found that survival fitted best with a model that combined three factors: (1) the performance index as a measure of general health; (2) the largest diameter of the largest metastasis as a measure of gross metastases; and (3) the serum level of alkaline phosphatase as an indicator of hepatic function and unmeasurable metastases.38 This system, the Helsinki University Central Hospital (HUCH) Working Formulation, divides stage IV uveal melanoma into three subcategories with an expected overall survival: exceeding 12 months (IVa), from 12 to 6 months (IVb), and <6 months (IVc). This division has been validated by the Ophthalmic Oncology Group. The median observed survival among 226 patients was 18.3 months for stage IVa, 10.0 months for stage IVb, and 4.6 months for stage IVc.39

The single strongest indicator of prognosis in the Working Formulation was the largest diameter of the largest metastasis,38 which was incorporated into the current TNM anatomic classification (Figure 1e).9 It divides systemic metastases into three categories: largest diameter of the largest metastasis up to 3 cm (M1a), from 3.1 to 8 cm (M1b), and larger than 8 cm (M1c).

Conjunctival melanoma

The TNM system for conjunctival melanoma has changed radically between editions, reflecting uncertainty as to the best way of classifying this tumour.2, 3, 9 The current system was unvalidated when published, but was recently shown to correlate with survival and, especially, with local recurrence.40, 41 In particular, T1 tumours differed from those of a higher T category.41

Prognosis of the primary tumour

Clinical prognostication

Institution-42, 43 and population-based44, 45, 46 retrospective studies have consistently shown that the location and size of the primary conjunctival melanoma are strong and independent predictors of prognosis. Primary tumours located at the limbus, their most common site, or displaced to the cornea47 carry a better prognosis than tumours in the bulbar, caruncular, and palpebral conjunctiva. These studies do not agree on the best cutoff points for categorising tumour size, but favour thickness over diameter as the best criterion. The current clinical TNM classification (Table 4) is based on location of the primary tumour and invasion of adjacent structures (Figures 1f and g).9

Table 4. Overview of the classification of malignant conjunctival melanoma in the seventh edition of the TNM classification9.

| Anatomic category | Clinical classification | Pathological classification |

|---|---|---|

| Tis | Melanoma in situ | Melanoma in situ |

| T1: Limbal and bulbar conjunctiva | ||

| T1a | ≤1 quadrant in size | ≤0.5 mm thick, invades substantia propria |

| T1b | >1–2 quadrants in size | >0.5–1.5 mm thick, invades substantia propria |

| T1c | >2–3 quadrants in size | >1.5 mm thick, invades substantia propria |

| T1d | >3 quadrants in size | — |

| T2: Palpebral, forniceal, and caruncular conjunctiva | ||

| T2a | Caruncle uninvolved ≤1 quadrant in size | ≤0.5 mm thick, invades substantia propria |

| T2b | Caruncle uninvolved >1 quadrant in size | >0.5–1.5 mm thick, invades substantia propria |

| T2c | Caruncle involved ≤1 quadrant in size | >1.5 mm thick, invades substantia propria |

| T2d | Caruncle involved >1 quadrant in size | — |

| T3: Local invasion | Eyeglobe, eyelid, nasolacrimal system, sinuses, or orbit involved | |

| T3a | Eyeglobe involved | — |

| T3b | Eyelid involved | — |

| T3c | Orbit involved | — |

| T3d | Sinus involved | — |

| T4: Central nervous system invasion | ||

| T4 | Central nervous system involved | Central nervous system involved |

Abbreviation: TNM, tumour, node, metastasis.

No staging system is implemented.

No other clinical feature has been consistently associated with prognosis of primary conjunctival melanoma. However, recurrence worsenes the prognosis independent of the characteristics of the antecedent primary tumour.42, 45 This highlights the importance of radical surgery combined with adequate adjuvant therapy such as topical mitomycin or brachytherapy. Adjuvant treatment is especially important in the presence of adjacent intraepithelial disease, variously designated primary acquired melanosis, or melanoma in situ.48

Following the advent of sentinel lymph node biopsy in assessing prognosis of cutaneous melanomas, such a procedure has also been considered for patients with conjunctival melanoma.49 It is not yet known whether sentinel node biopsy influences the outcome, so that this procedure is mostly viewed as a prognostic one. A population-based analysis suggested that lymph node metastasis is not frequent enough to justify a sentinel node biopsy if the primary tumour is limbal and <2 mm in thickness (Figures 1f and g).50 Indeed, a positive biopsy so far has not been reported if both these criteria were met.51

Histopathological and genetic prognostication

Although many histopathological featuers of conjunctival melanoma have been associated with prognosis in retrospective studies, none has been consistently and independently verified after taking into account the location and the size of the tumour.52 The current pTNM system9 relies on tumour thickness and invasion of substantia propria, setting cut-points at 0.5 and 1.5 mm (Table 4). Genetic prognostic markers are not available.

Prognosis after dissemination

Several small series suggest that overall survival is longer if initial metastases are found in regional lymph nodes rather than systemically,50 especially when the regional metastases are resectable. This is consistent with the theory that such regional metastasis would represent an earlier stage, which might in some instances be curable. The current TNM system uses only categories N1 and M1 to indicate the presence of any regional or systemic metastasis, respectively.

By and large, conjunctival melanomas resemble their cutaneous counterparts in epidemiology45 and behaviour. The classification of cutaneous melanoma divides regional lymph node metastases into three categories according to the number of nodes involved, and categorises systemic metastases by the tissues involved and by the serum lactate dehydrogenase level.9

Retinoblastoma

Prognostication for retinoblastoma has two aims: (1) to predict the chances of saving the eye and vision and (2) to predict survival. Because retinoblastoma is rare and its treatment is typically centralised, only a brief outline of the general principles is provided below.

Prognosis of the eye and vision

For decades, the prognosis of an eye with retinoblastoma has been asssessed with the Reese–Ellsworth classification. Although still used in the recent literature to allow comparison with older publications, this classification has become outdated. It was developed at a time when the main treatment options were enucleation, external beam and plaque radiotherapy, cryocoagulation, and photocoagulation. The introduction of chemoreduction and thermotherapy required a new classification, known alternatively as the ABC or International Classification, which exists in several variants.53, 54 As reviewed elsewhere, they divide intraocular retinoblastoma into five categories A to E based on anatomic extent (Figure 1h).55

A mnemonic devised by Carol and Jerry Shields helps memorisation of the main categories and may be useful to residents and paediatric ophthalmologists who do not manage retinoblastoma themselves. Group A refers to eyes with small tumours located ‘away' from the optic disc and foveola; group B with ‘bigger tumours' group C with ‘confined seeding close to the tumour' group D with ‘diffuse seeding', and group E with ‘extensive disease'. According to recent estimates, the chances of saving the eye range from almost 100% for group A to 48% for group E.54, 56 The management of retinoblastoma continues to evolve, and these figures are still likely to improve over time.

The TNM system for retinoblastoma9 is based closely on the international classification, but has so far not been widely used in the literature. Category T1a largely corresponds with group A, categories T1b and T1c with group B (Figure 1h), category T2a with group C, category T2b with group D, and category T3a and T3b with group E. Category T4 subdivisions correspond to extraocular disease, which is not covered in the international classification. The N categories differentiate between regional (N1) and distant (N2) lymph node metastasis, and the M1 category is subdivided based on the sites of systemic metastases.

Prognosis for survival

The life prognosis of children with retinoblastoma depends on whether or not the tumour has spread extrasclerally and whether it has metastasised. The spread to orbit can take place anteriorly through aqueous outflow passages or posteriorly through massive invasion of the choroid and postlaminar invasion of the optic nerve, characteristics that are implemented in the pathological pTNM classification.9 Corresponding survival figures are not yet available.

No TNM staging is currently implemented for retinoblastoma. An independent International Staging is in use, however, which divides patients into stage 0 (treated conservatively), stage I (enucleated, without residual tumour), stage II (enucleated, microscopic residual tumour), stage III (orbital or regional lymph node extension), and stage IV (systemic metastasis or central nervous system extension).57, 58

Children with hereditary retinoblastoma have a 4% risk of developing an ectopic primitive intracranial neuroblastic tumour, known as trilateral retinoblastoma,59 and are also prone to second cancers later in life. Currently, it is not possible to predict whether such tumours will develop, even when the exact mutation of the retinoblastoma gene is known.

Ocular adnexal lymphoma

The novel TNM classification of ocular adnexal lymphoma, which defines more precisely than ever before the anatomical location and extent of the tumour, as well as involvement of regional lymph nodes and structures, such as the parotid gland, has been reviewed in detail elsewhere.7

The future of the TNM systen

The TNM system has periodically become under attack1, 9 because of progress in molecular and genetic prognostication of cancer and the advent of computerised multivariate analyses, which allow easy entry of clinical, histopathological, biochemical, and genetic data to produce an individualised survival estimate. The best systems, like the Liverpool Uveal Melanoma Prognosticator Online,60 even return relative survival estimates. This method compares survival between similar cancer patients and matched general population and so obviates the need to determine the actual cause of death, which is not always known with certainty. In addition, it takes simultaneously into account competing causes of death similar to cumulative incidence analysis,37 unlike traditional Kaplan–Meier and Cox analyses.

Advocates of the TNM system have responded by including limited non-anatomic factors into stage groupings,1 and by encouraging cancer registries to collect not only TNM classification data but also histopathological, biochemical, and genetic prognostic factors.9

The TNM system may also be used to stratify tumours after prognostication based on biochemistry or genetics. For example, the prospective data collected for validation of gene expression profiling of uveal melanoma36 indicates that 7% of class 2 tumours of stage I metastasised during follow-up as compared with 27% of stage II and 32% of stage III melanomas, presuming that all metastases would have derived from class 2 tumours (in practice, three patients with metastases had a class 1 melanoma). Thus, the TNM stage seems to enhance gene expression profiling by indicating not only if symptomatic metastases will occur but also when dissemination is likely to develop.

Those who maintain that other prognostic factors should complement rather than replace the TNM classification are likely to be correct.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation and the Helsinki University Central Hospital Research Fund (TYH 2010204 and TYH 2012106).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at the Cambridge Ophthalmological Symposium on Cancer of the Eye, 13 September 2012 at St John's College, Cambridge, UK by Tero Kivelä.

References

- Sobin LH. TNM: evolution and relation to other prognostic factors. Semin Surg Oncol. 2003;21:3–7. doi: 10.1002/ssu.10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours5th ed.Wiley: New York; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours6th ed.Wiley-Liss: New York; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Finger PT. Do you speak ocular tumor. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:13–14. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01838-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch CM, Soong SJ, Atkins MB, Buzaid AC, Cascinelli N, Coit DG, et al. An evidence-based staging system for cutaneous melanoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:131–149. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.3.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger PT. The 7th edition AJCC staging system for eye cancer: an international language for ophthalmic oncology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1197–1198. doi: 10.5858/133.8.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupland SE, White VA, Rootman J, Damato B, Finger PT. A TNM-based clinical staging system of ocular adnexal lymphomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1262–1267. doi: 10.5858/133.8.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujala E, Damato B, Coupland SE, Desjardins L, Bechrakis NE, Grange J-D, et al. Staging of ciliary body and choroidal melanoma based on anatomic extent: a collaborative study by the European Ophthalmic Oncology Group J Clin Oncol(in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Edge SE, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti AIII.(eds)AJCC Cancer Staging Manual7th ed.Springer: New York; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Ainbinder DJ, Esmaeli B, Groo SC, Finger PT, Brooks JP. Introduction of the 7th edition eyelid carcinoma classification system from the American Joint Committee on Cancer-International Union Against Cancer staging manual. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1256–1261. doi: 10.5858/133.8.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rootman J, White VA. Changes in the 7th edition of the AJCC TNM classification and recommendations for pathologic analysis of lacrimal gland tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1268–1271. doi: 10.5858/133.8.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damato B, Eleuteri A, Taktak AF, Coupland SE. Estimating prognosis for survival after treatment of choroidal melanoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Finger PT, Yu GP, Razzaq L, Jager MJ, de Keizer RJ, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of biopsy-proven iris melanoma: a multicenter international study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:57–64. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujala E, Kivela T. Tumor, node, metastasis classification of malignant ciliary body and choroidal melanoma: evaluation of the 6th edition and future directions. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1135–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean IW, Saraiva VS, Burnier MN. Pathological and prognostic features of uveal melanomas. Can J Ophthalmol. 2004;39:343–350. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(04)80004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angi M, Damato B, Kalirai H, Dodson A, Taktak A, Coupland SE. Immunohistochemical assessment of mitotic count in uveal melanoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:e155–e160. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshari A, McLean IW. Uveal melanoma: mean of the longest nucleoli measured on silver-stained sections. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1160–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jamal RT, Mäkitie T, Kivelä T. Nucleolar diameter and microvascular factors as independent predictors of mortality from malignant melanoma of the choroid and ciliary body. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2381–2389. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folberg R, Rummelt V, Parys-Van Ginderdeuren R, Hwang T, Woolson RF, Pe'er J, et al. The prognostic value of tumor blood vessel morphology in primary uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31470-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkitie T, Summanen P, Tarkkanen A, Kivelä T. Microvascular loops and networks as prognostic indicators in choroidal and ciliary body melanomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:359–367. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss AJ, Alexander RA, Jefferies LW, Hungerford JL, Harris AL, Lightman S. Microvessel count predicts survival in uveal melanoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2900–2903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkitie T, Summanen P, Tarkkanen A, Kivelä T. Microvascular density in predicting survival of patients with choroidal and ciliary body melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2471–2480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Maniotis AJ, Majumdar D, Pe'er J, Folberg R. Uveal melanoma cell staining for CD34 and assessment of tumor vascularity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2533–2539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken MD, Worley LA, Ehlers JP, Harbour JW. Gene expression profiling in uveal melanoma reveals two molecular classes and predicts metastatic death. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7205–7209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken MD, Worley LA, Tuscan MD, Harbour JW. An accurate, clinically feasible multi-gene expression assay for predicting metastasis in uveal melanoma. J Mol Diagn. 2010;12:461–468. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damato B, Coupland SE. Translating uveal melanoma cytogenetics into clinical care. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:423–429. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CL, Ganguly A, Bianciotto CG, Turaka K, Tavallali A, Shields JA. Prognosis of uveal melanoma in 500 cases using genetic testing of fine-needle aspiration biopsy specimens. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worley LA, Onken MD, Person E, Robirds D, Branson J, Char DH, et al. Transcriptomic versus chromosomal prognostic markers and clinical outcome in uveal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1466–1471. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisley K, Cottam DW, Rennie IG, Parsons MA, Potter AM, Potter CW, et al. Non-random abnormalities of chromosomes 3, 6, and 8 associated with posterior uveal melanoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1992;5:197–200. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschentscher F, Prescher G, Zeschnigk M, Horsthemke B, Lohmann DR. Identification of chromosomes 3, 6, and 8 aberrations in uveal melanoma by microsatellite analysis in comparison to comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;122:13–17. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(00)00266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damato B, Dopierala JA, Coupland SE. Genotypic profiling of 452 choroidal melanomas with multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6083–6092. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopierala J, Damato BE, Lake SL, Taktak AF, Coupland SE. Genetic heterogeneity in uveal melanoma assessed by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4898–4905. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake SL, Coupland SE, Taktak AF, Damato BE. Whole-genome microarray detects deletions and loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 3 occurring exclusively in metastasizing uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4884–4891. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaarwater J, van den Bosch T, Mensink HW, van Kempen C, Verdijk RM, Naus NC, et al. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification equals fluorescence in situ hybridization for the identification of patients at risk for metastatic disease in uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2012;22:30–37. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32834e6a67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken MD, Worley LA, Davila RM, Char DH, Harbour JW. Prognostic testing in uveal melanoma by transcriptomic profiling of fine needle biopsy specimens. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:567–573. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.060077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken MD, Worley LA, Char DH, Augsburger JJ, Correa ZM, Nudleman E, et al. Collaborative Ocular Oncology Group report number 1: prospective validation of a multi-gene prognostic assay in uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1596–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujala E, Mäkitie T, Kivelä T. Very long-term prognosis of patients with malignant uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4651–4659. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskelin S, Pyrhönen S, Hahka-Kemppinen M, Tuomaala S, Kivelä T. A prognostic model and staging for metastatic uveal melanoma. Cancer. 2003;97:465–475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskelin S, Piperno-Neumann S, Desjardins L, Schmittel A, Bechrakis N, Midena E, et al. Validating the Helsinki University Central Hospital (HUCH) working formulation for staging metastatic uveal melanoma Acta Ophthalmol Scand (Suppl) 200785doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01063_3573.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yousef YA, Finger PT. Predictive value of the seventh edition American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for conjunctival melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:599–606. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CL, Kaliki S, Al-Dahmash SA, Lally SE, Shields JA. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Clinical Classification Predicts Conjunctival Melanoma Outcomes. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28:313–323. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3182611670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CL, Shields JA, Gunduz K, Cater J, Mercado GV, Gross N, et al. Conjunctival melanoma: risk factors for recurrence, exenteration, metastasis, and death in 150 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1497–1507. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.11.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastassiou G, Heiligenhaus A, Bechrakis N, Bader E, Bornfeld N, Steuhl KP. Prognostic value of clinical and histopathological parameters in conjunctival melanomas: a retrospective study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:163–167. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norregaard JC, Gerner N, Jensen OA, Prause JU. Malignant melanoma of the conjunctiva: occurrence and survival following surgery and radiotherapy in a Danish population. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1996;234:569–572. doi: 10.1007/BF00448801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomaala S, Eskelin S, Tarkkanen A, Kivelä T. Population-based assessment of clinical characteristics predicting outcome of conjunctival melanoma in whites. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3399–3408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missotten GS, Keijser S, de Keizer RJ, de Wolff-Rouendaal D. Conjunctival melanoma in the Netherlands: a nationwide study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:75–82. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomaala S, Aine E, Saari KM, Kivelä T. Corneally displaced malignant conjunctival melanomas. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:914–919. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)00967-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damato B, Coupland SE. Conjunctival melanoma and melanosis: a reappraisal of terminology, classification and staging. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2008;36:786–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeli B, Eicher S, Popp J, Delpassand E, Prieto VG, Gershenwald JE. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for conjunctival melanoma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17:436–442. doi: 10.1097/00002341-200111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomaala S, Kivelä T. Metastatic pattern and survival in disseminated conjunctival melanoma: implications for sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:816–821. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomaala S, Kivelä T. Sentinel lymph node biopsy guidelines for conjunctival melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:235. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3282fafd21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomaala S, Toivonen P, Al-Jamal R, Kivelä T. Prognostic significance of histopathology of primary conjunctival melanoma in Caucasians. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32:939–952. doi: 10.1080/02713680701648019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novetsky DE, Abramson DH, Kim JW, Dunkel IJ. Published international classification of retinoblastoma (ICRB) definitions contain inconsistencies—an analysis of impact. Ophthalmic Genet. 2009;30:40–44. doi: 10.1080/13816810802452168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Au AK, Czyz C, Leahey A, Meadows AT, et al. The International Classification of Retinoblastoma predicts chemoreduction success. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2276–2280. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CL, Fulco EM, Arias JD, Alarcon C, Pelligrini M, Rishi P, et al. Retinoblastoma frontiers with intravenous, intra-arterial, periocular, and intravitreal chemotherapy Eye (Lond)e-pub ahead of print 21 September 2012; doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shields CL, Ramasubramanian A, Thangappan A, Hartzell K, Leahey A, Meadows AT, et al. Chemoreduction for group E retinoblastoma: comparison of chemoreduction alone versus chemoreduction plus low-dose external radiotherapy in 76 eyes. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantada G, Doz F, Antoneli CB, Grundy R, Clare Stannard FF, Dunkel IJ, et al. A proposal for an international retinoblastoma staging system. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:801–805. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten-van Meeteren AY, van der Valk P, Moll AC, Imhof SM, de Graaf P, Siregar NCh, et al. International retinoblastoma staging system helps to bridge the gap. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:733. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivela T. Trilateral retinoblastoma: a meta-analysis of hereditary retinoblastoma associated with primary ectopic intracranial retinoblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1829–1837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.6.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damato B. Progress in the management of patients with uveal melanoma. The 2012 Ashton Lecture. Eye (Lond) 2012;26:1157–1172. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]