Summary

Achievements in malaria control could inform efforts to control the increasing global burden of dengue. Better methods for quantifying dengue endemicity—equivalent to parasite prevalence surveys and endemicity mapping used for malaria—would help target resources, monitor progress, and advocate for investment in dengue prevention. Success in controlling malaria has been attributed to widespread implementation of interventions with proven efficacy. An improved evidence base is needed for large-scale delivery of existing and novel interventions for vector control, alongside continued investment in dengue drug and vaccine development. Control of dengue is unlikely to be achieved without coordinated international financial and technical support for national programmes, which has proven effective in reducing the global burden of malaria.

Malaria's fall and dengue's rise

Malaria has been one of the major challenges to global health during the past century. In 1900, 58% of the world's land area was estimated to have sustained stable malaria transmission.1 More than a million deaths annually have been attributed to malaria throughout the latter half of the 20th century,2,3 most in children younger than 5 years, with countries of sub-Saharan Africa bearing the largest toll.4,5 However, mounting evidence suggests a decline in the global burden of malaria, a decrease that began in the mid 20th century in some regions but was most notable in parts of Africa over the past decade.1,2,6–8 This reduction has led to renewed focus among the malaria community on a goal of malaria elimination in many countries.9 While malaria has been in decline, the geographical range and disease burden of another tropical infectious disease has been on the rise.

Dengue has emerged as an increasing public health problem over the past 50 years, particularly in southeast Asia and Central and South America,10 with an unknown but possibly substantial level of transmission in Africa.11 Like malaria, dengue is a vector-borne disease of the tropics and is a major cause of morbidity in endemic areas, particularly in children and young adults;12 however, the scale of dengue morbidity and mortality is uncertain and thought to be less than that of malaria. Dengue is caused by four distinct but related viruses (serotypes DENV 1–4) that are transmitted among people by aedes mosquitoes. The disease burden and geographical range of dengue have expanded, from about 15 000 cases reported annually from fewer than ten countries during the 1960s to almost one million cases a year across more than 60 countries in 2000–2005.13 As a result, dengue has been identified as an important threat to global public health.10 In view of this rising challenge, could lessons learned from global efforts to control malaria help inform strategies to prevent and perhaps reverse the spread of dengue?

In this Personal View, we compare and contrast malaria and dengue with respect to epidemiology, current and future interventions available for prevention and control, and their prioritisation as global health issues, in terms of funding, capacity, and international collaborations. We also argue that improved data on the range and endemicity of dengue are a vital component of global prevention and control efforts.

Effect of vectors on epidemiology

The geographical ranges of both malaria and dengue are limited by the spatial extent of the competent vectors—particular species of anopheles and aedes mosquitoes, respectively. The bionomics of the vectors shapes the epidemiology of each disease. With a few exceptions, anopheles mosquitoes favour rural environments, mainly because of their larval habitat requirements.14–16 By contrast, the primary vector of dengue, Aedes aegypti, thrives in urban environments where abundant container breeding sites in and around human habitations allow immature vectors to develop and adults to feed and rest close to high densities of humans, their preferred host for blood meals.17

Although aedes mosquitoes have a restricted flight range of about 100 m in the field,18 passive transport of Ae aegypti by land and, in immature stages, by sea led to their re-establishment in countries of South and Central America, from which they had previously been eliminated in the mid 20th century,19 and dispersal throughout southeast Asia during and after World War 2.20 The geographical range of a secondary dengue vector, Aedes albopictus, has also expanded substantially over the past 30 years, but it is a less efficient vector and is not currently seen as a major contributor to or risk factor for increased dengue transmission.21

The growing mobility of viraemic people, both within endemic settings and into new regions by increased domestic and international travel and migration, has been key in driving the global expansion of dengue in recent decades.22 This movement has created conditions in which multiple virus serotypes cocirculate, leading to an increase in the risk of sequential infections and severe disease. By contrast, the ecological requirements of anopheles mosquitoes have not facilitated their dispersal,23 and the unprecedented urbanisation that has characterised the past century is associated with reduced risk of malaria transmission, at least in the African setting.4

Quantifying disease burden and distribution

The global burden of a disease is a function of both its geographical range and the intensity of transmission in affected areas. By both these measures, the global burden of malaria has unequivocally decreased over the past century,1 although this decline has not been consistent across all malaria-endemic countries.8 Serious efforts to define the geographical limits and intensity of malaria transmission go back to the mid 20th century,24–26 when global control and eradication efforts were gathering momentum. A renewed effort to quantify the magnitude and distribution of the burden of malaria has seen new epidemiological and cartographic techniques applied to multiple collated data sources to model the spatial extent of malaria transmission and so to estimate populations at risk of exposure.27–29 These calculations place 2·4 billion people living in 87 countries at risk of Plasmodium falciparum infection in 2007,27 resulting in around 450 million clinical cases of P falciparum malaria annually.29 The inclusion of uncertainty intervals around estimates has been a major step forward with these cartographic methods.30 For dengue, assessments of the spatial extent of transmission have been based largely on empirical data of reported dengue cases from endemic and epidemic settings, with models then fitted to correlate the observed distribution with environmental and climatic characteristics.31,32 WHO estimates that 50 million dengue virus infections occur every year across about 100 countries, representing a population at risk of 2·5 billion people,10 although this number could be an underestimate of the true burden.33 The most recent assessment of the global distribution of dengue identifies 128 countries with good evidence of transmission and puts almost four billion people at risk.11

The intensity of transmission of both malaria and dengue is spatially and temporally heterogeneous.34–37 The most commonly used measure of malaria endemicity is the parasite prevalence rate, which represents the proportion of a population with malaria parasites detectable in their blood.38 This measure has been used widely in malaria surveys throughout the past century and has been used to generate the first evidence-based global map of malaria endemicity in 2007, recently updated for 2010 (figure).39 Another key metric of malaria transmission risk is the entomological inoculation rate, which represents the rate at which people are bitten by infectious mosquitoes.40 The relationship between the entomological inoculation rate and the parasite prevalence rate is non-linear.41,42 Empirical measurements for the entomological inoculation rate have been gathered less routinely and consistently than for the parasite prevalence rate, making the former a less useful measure for global endemicity mapping.43 Consequently, the entomological inoculation rate and other important metrics for malaria have been inferred with modelled relationships44 between them and extensive maps of parasite rates.39

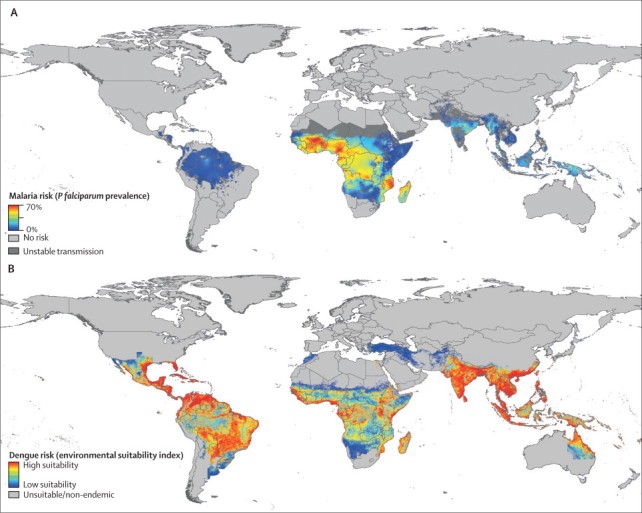

Figure.

Global risk of malaria and dengue

Annual mean prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria for 2010 (A). Reprinted from reference 39, with permission of BioMed Central. Global dengue risk (B), based on data from WHO, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, GIDEON online, ProMED, DengueMap, Eurosurveillance, and other published work. Reprinted from reference 55, with permission of the Massachusetts Medical Society.

Epidemiological data on the global burden of dengue rely almost entirely on reports of clinically apparent disease, derived from national surveillance systems10,45–52 and, in a few cases, from prospective longitudinal studies.53,54 The figure shows a map of dengue risk that combines disease notification and outbreak data from international organisations, case reports on returning travellers, published scientific literature on dengue occurrence, and a biological model of environmental suitability.55 Serological data from longitudinal studies56–62 permit estimation of infection incidence in a population, including the ratio of symptomatic to inapparent infections. This type of study depends, however, on follow-up of cohorts, which needs far greater investment of time and money compared with cross-sectional surveys that are used to obtain estimates of the malaria parasite prevalence rate.

Traditional indicators of the abundance of aedes mosquitoes, based on immature vector stages (house index, container index, Breteau index), are collected routinely in many dengue-endemic countries, but their correlation with human infection and disease is poor.63,64 Counts of Ae aegypti pupae per person might correlate more closely with adult vector density and, therefore, potential for dengue transmission.36,65 Direct measurement of the density of adult Ae aegypti—with PCR to ascertain the proportion infected with dengue virus—would be most informative, but this approach is logistically and financially demanding to do on a sufficiently large scale in view of the difficulty in sampling adult vectors and the expected large variance in both adult numbers and prevalence of infection.36,66,67

For both malaria and dengue, the relationship between the risk of infection and the risk of disease is non-linear and depends on host immune status and age at infection.68–72 The most appropriate metric will be determined by its purpose. Clinical case numbers are relevant to the prediction of demand for diagnostic tests, health-care services, and treatments. WHO also defines laboratory-confirmed clinical dengue cases of any severity as the most appropriate endpoint for dengue vaccine trials.73 However, for describing transmission extent and intensity, especially when making comparisons between countries and over time, reliance on case-burden data is fraught with issues of inconsistent reporting patterns (both spatially and temporally), differences in clinical case definitions, over-reporting when laboratory testing is not routine, and under-reporting of patients who do not present to health services or who are managed as outpatients only.74,75 A measure of the incidence of infection, rather than disease, might also be an appropriate endpoint for trials of dengue vector-control interventions in the community; not only is active surveillance of clinical outcomes more resource-intensive than cross-sectional blood sampling but also a large (and variable) proportion of prevented infections are likely to be asymptomatic.76 Therefore, a smaller sample size will be needed to show an effect on infection rates, compared with a clinical effect of the same size, because of the higher overall event rate for infections versus clinical cases.

What alternative metric could be used to measure dengue endemicity, equivalent to the parasite rate for malaria? Virological markers of dengue—such as viraemia and presence of the NS1 antigen in blood—are short-lived compared with untreated malaria parasitaemia, disappearing about 1 week after onset of clinical symptoms.77 Furthermore, the magnitude and duration of viraemia varies with severity of disease, virus serotype, and host immune status.78–80 Cross-sectional age-stratified serological surveys of dengue-specific IgG can indicate the prevalence of past exposure to dengue virus but are confounded by antibodies directed against other flaviviruses, where these cocirculate. Cross-sectional seroprevalence surveys of dengue-specific IgM might indicate recent infection with dengue virus or other flaviviruses. Aside from potential low specificity, interpretation is complicated by the variable kinetics of the IgM response, most importantly, the difference between first and subsequent infections,81 making comparison of population-based IgM surveys between epidemiological settings difficult. Population-based surveys of dengue neutralising antibody, measured by the plaque reduction neutralisation test, would provide the most sensitive and specific information on virus transmission patterns, including serotype-specific data and multiple heterotypic exposures. However the plaque reduction neutralisation test is substantially more resource-intensive than standard IgM and IgG immunoassays. Finding the appropriate metric to measure the endemic level of dengue is a clear research priority.

Interventions for prevention and control

Success in controlling malaria over the past century has been attributed predominantly to widespread implementation of insecticide-treated bednets, household spraying of residual insecticides, and effective drugs to reduce mortality and interrupt transmission.6 The countries in which little progress has been made with malaria control are commonly those where political instability, war, or economic underdevelopment have hindered widespread implementation of these interventions.82

The situation with dengue is different; vector control is the only currently available approach for prevention and control and is pursued mainly through reduction of larval development sites, via environmental clean-up campaigns to dispose of discarded or unnecessary water containers, and prevention of mosquito access to breeding sites. Other methods include treatment of water-storage vessels with larvicide83 or predacious copepods84 to kill larval stages. The effectiveness of these interventions has been demonstrated at a local community level84–86 but rarely on a large scale or across diverse epidemiological settings (not since the Ae aegypti eradication campaign of the 1950s), with Singapore and Cuba perhaps the only exceptions.87–89 Success of such efforts depends on sustained community support and participation.90 However, even when mosquito populations have been reduced drastically, as in Singapore, cases of dengue still occur,91 with evidence of increasing risk of clinical disease associated with older age at first infection.72,92 Killing adult mosquitoes has a theoretically greater effect on transmission than does targeting larvae. Space-spraying of insecticide to kill adult vectors in and around households is popular because it represents a highly visible response to localised outbreaks of dengue, but a sustained effect on virus transmission has not been demonstrated.10,93

Indoor residual spraying of insecticide has a long history of use in malaria control, and its importance as a key intervention for interruption of malaria transmission has been reaffirmed by WHO.94 Many behavioural characteristics of anopheles vectors that make indoor residual spraying an effective malaria intervention, such as their anthropophagic biting preferences and tendency to rest and feed indoors,14–16 are common also to aedes dengue vectors. There is some evidence that high household coverage of indoor residual spraying in an outbreak setting could reduce dengue transmission.95 Use of this method to control yellow fever in the Americas in the mid 20th century had a concomitant and striking effect on dengue transmission, but there are very few reports of the application of indoor residual spraying specifically to control dengue.95–98 The preference of aedes vectors for daytime activity and feeding means that insecticide-treated bednets are ineffective for dengue control. Findings of several small trials99–101 of other insecticide-treated materials, such as curtains and water-jar covers, indicate a reduction in indices of household vectors, and larger trials are warranted to investigate effectiveness in a range of epidemiological settings.

Early diagnosis and treatment with effective drugs reduces morbidity and mortality from malaria. International guidelines recommend parasitological confirmation, when possible, of all suspected cases of malaria and prompt initiation of treatment to prevent progression to severe disease.102 Timeliness is also very important for effective clinical management of dengue; progression from an acute febrile phase to non-complicated recovery, or through a critical phase characterised by thrombocytopenia and capillary permeability with potential for haemorrhage and shock, takes place over 3–7 days.10

Unlike malaria, no specific treatment for dengue is available, and clinical management entails close haematological monitoring, fluid-replacement therapy as required, and recognition of warning signs of severe disease. Although serological, molecular, and rapid diagnostic tests for dengue are widely available, the expense, waiting time, and large case numbers mean that clinical management and case reporting in most endemic settings is based on clinical diagnosis alone. Increasing availability of rapid diagnostic tests could theoretically improve timeliness and accuracy of dengue diagnoses. However, studies of the effect of test results on clinical management and outcome of dengue cases, including cost-effectiveness studies, are needed to inform recommendations for widespread use. Demand for routine diagnostic testing for dengue could increase substantially if an antiviral drug were available.

Research efforts towards vaccines against malaria and dengue are similarly complicated by (among other challenges) the antigenic or serotypic variability of the organisms.103–105 A longlasting highly effective dengue vaccine should be much easier to develop than an equivalent malaria vaccine because of the relative antigenic complexity of the two pathogens and the longevity of immune responses to viral infections, compared with those to malaria parasites.106 However, developers of a dengue vaccine must contend with the theoretical risk of severe disease associated with sequential infection with a heterologous serotype and, thus, aim to develop a tetravalent vaccine.106 Candidate vaccines for malaria and dengue are in phase 3 field trials,107,108 but despite publication of promising clinical trial data for the leading malaria vaccine candidate,109 a substantial vaccine-mediated reduction in the global burden of either disease is not imminent. Thus, vector control, effective diagnosis, and clinical management remain the cornerstones of control for both diseases, for the foreseeable future.

The challenge now in malaria control is equitable and effective implementation of interventions that have proven efficacy. However, to tackle the increasing burden of dengue, well designed and controlled field trials are needed of both existing and novel vector-control interventions, linked to detailed epidemiological data, to improve the evidence base and inform local and national dengue-control strategies. Further challenges for evaluation of dengue interventions might include the effect of human movement on patterns of transmission, and the pronounced temporal and spatial heterogeneity in transmission, which will necessitate very large cluster-randomised study designs. These issues are also likely to be challenges for malaria control though the elimination or eradication phases.

Prioritisation and investment of funding and resources

Malaria control throughout the past century has been a combined effort of national, regional, and international programmes. The global malaria eradication programme launched in 1955 by WHO was the largest coordinated international public health campaign in history.110 With an intensive strategy of vector control using residual insecticides, combined with detection and treatment of cases, 22 countries in the Americas and 27 in Europe achieved malaria elimination between 1950 and 1978.111 Despite these successes, the goal of elimination was not met universally and was never proposed for sub-Saharan Africa; in 1969, WHO's strategy was revised to one of control.112

Efforts to control dengue also benefited from an elimination campaign in the mid 20th century; in 1947, the Pan-American Health Organization adopted a proposal by Brazil for a so-called hemispheric (pan-American) strategy to remove the Ae aegypti vector.113 Although the aim of this campaign was eradication of urban yellow fever, which shares the same vector as dengue, the successful elimination by 1967 of Ae aegypti from all countries of the Americas (except for the USA, Venezuela, and the Caribbean region)114 saw a substantial reduction in dengue morbidity across this region.115 Unfortunately, this campaign had the same outcome as the global malaria eradication programme, with a reversion to a strategy of control because of a combination of reduced political will, insufficient financing to sustain intensive control efforts, and increasing decentralisation of national public health authorities, among other factors.115,116 The Ae aegypti vector re-established itself in areas from which it had been eliminated, with a resultant rise in dengue epidemics in the Americas throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In southeast Asia, an elimination goal for dengue or its vector has never been proposed formally.117

Efforts to control malaria during the past 15 years have intensified after the development of international initiatives to coordinate and finance the scale-up of interventions, beginning with the Roll Back Malaria Partnership, launched in 1998, and the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, founded in 2002. More recently, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has allocated substantial funds to malaria control and eradication efforts. These initiatives recognise the need for external funding and support to malaria-endemic countries to achieve coverage of interventions at a level that will affect transmission and morbidity. An estimated US$9·9 billion was committed by international donor agencies for malaria control in endemic countries between 2002 and 2010.118 By contrast, vector-control interventions for dengue remain the financial and logistical responsibility of national control programmes in endemic countries, which are funded from national budgets with no substantial or sustained external sources of financing. Dengue is a high public health priority in endemic countries,119 but the main target of spending is responsive vector-control activities around reported cases, combined with passive case surveillance and some routine virus and vector surveillance. Budgets are usually insufficient to implement these actions fully, let alone to sustain breeding source reduction activities, larval control, and environmental management, which might be more effective120,121 but are highly resource-intensive.

It is difficult to see how the continuing geographical spread and increasing intensity of dengue transmission can begin to be reversed without support in coordination and financing from outside endemic countries. Support should include applied research to improve the evidence base for existing vector-control techniques, for novel interventions such as transfection of Wolbachia spp into Ae aegypti to suppress dengue transmission,122 and for strategic planning to implement and finance a future vaccine. Even when a dengue vaccine becomes a reality, external assistance for financing and implementation will be needed by some endemic countries, as will continued concerted efforts in vector control. Unlike malaria, which receded from southern Europe in the mid 20th century, aedes mosquitoes, and possibly dengue, could continue to expand into warmer areas of high-income countries, including Australia, the USA, and southern Europe.31,32 This possibility should provide any additional impetus needed for dengue to be viewed as more than a neglected tropical disease. The burden of morbidity, mortality, and economic loss attributable to dengue is not comparable with that caused by malaria. However, the coordinated initiatives for funding of regional and global collaborative research and control activities, which have proven effective to address the global burden of malaria,123 could also drive similar gains in dengue control.

Moving forward

Based on lessons learned from malaria control, we propose that development of better methods to quantify dengue endemicity and disease burden, permitting comparisons across countries and regions, is an essential step towards halting the current rise in disease range and intensity. We must be able to quantify these increases accurately so we can establish baselines against which future trends can be compared. Analysis of the clinical and demographic profile of acute cases can tell us much about local dengue transmission dynamics, but improved indices of transmission—including means of accounting for asymptomatic infections—that can be measured at a population level and within specific subgroups would provide a much more complete picture of local transmission patterns. This information can guide effective surveillance and implementation of interventions, including future vaccines. Use of serological markers of dengue infection in epidemiological studies has some limitations, but age-stratified serosurveys of neutralising antibodies against the virus probably represent the best equivalent to the malaria parasite prevalence survey for population-based estimates of the incidence of infection. Improved entomological measures of risk for dengue transmission, based on density of the adult vector and infection prevalence, could complement these estimates but might also be inferred, similar to malaria, from measurement of incidence in human populations.

Improved estimates of the dengue disease burden would inform economic analyses of vector-control activities and future vaccination strategies. Effective implementation of these interventions could be achievable within the national budgets of a few dengue endemic countries, but many national dengue control programmes would benefit from coordinated international funding to achieve adequate coverage, as has proven effective in malaria control. This fact reinforces the importance of developing improved indicators of local, regional, and global dengue endemicity and disease burden, to advocate for funding directed to areas of greatest need, to identify locations where interventions are most likely to succeed, and to monitor future progress of disease prevention efforts, including vaccines.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

KLA is supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Li Ka Shing Foundation. SIH is funded by a Senior Research Fellowship from the Wellcome Trust and is supported by the Li Ka Shing Foundation, the RAPIDD program of the Science and Technology Directorate, Department of Homeland Security, and the Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health. This research was also supported partly by the IDAMS Project (grant no 281803) within the 7th Framework Programme of the European Commission. The sponsors had no role in preparation of the manuscript or the decision to publish. We thank Cameron Simmons, Oliver Brady, Peter Gething, Thomas Scott, Philip McCall, and Jeremy Farrar for valuable comments and suggestions during the preparation of this manuscript; and Katherine Battle for proofreading.

Contributors

SIH conceived of and contributed to writing of the paper. KLA wrote the paper.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gething PW, Smith DL, Patil AP, Tatem AJ, Snow RW, Hay SI. Climate change and the global malaria recession. Nature. 2010;465:342–345. doi: 10.1038/nature09098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay SI, Guerra CA, Tatem AJ, Noor AM, Snow RW. The global distribution and population at risk of malaria: past, present, and future. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:327–336. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01043-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter R, Mendis KN. Evolutionary and historical aspects of the burden of malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:564–594. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.4.564-594.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hay SI, Guerra CA, Tatem AJ, Atkinson PM, Snow RW. Urbanization, malaria transmission and disease burden in Africa. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:81–90. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snow RW, Omumbo JA. Malaria. In: Jamison DT, Feachem RG, Makgoba MW, editors. Disease and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. 2nd edn. World Bank; Washington: 2006. pp. 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Meara WP, Mangeni JN, Steketee R, Greenwood BM. Changes in the burden of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:545–555. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snow RW, Marsh K. Malaria in Africa: progress and prospects in the decade since the Abuja Declaration. Lancet. 2010;376:137–139. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60577-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray CJL, Rosenfeld LC, Lim SS. Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:413–431. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feachem RG, Phillips AA, Hwang J. Shrinking the malaria map: progress and prospects. Lancet. 2010;376:1566–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61270-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO . Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brady OJ, Gething PW, Bhatt S. Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gubler DJ. Epidemic dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever as a public health, social and economic problem in the 21st century. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:100–103. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroeger A, Nathan MB. Dengue: setting the global research agenda. Lancet. 2006;368:2193–2195. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69873-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinka ME, Rubio-Palis Y, Manguin S. The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in the Americas: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:72. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S. The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in Africa, Europe and the Middle East: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:117. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S. The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in the Asia-Pacific region: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:89. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott TW, Chow E, Strickman D. Blood-feeding patterns of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) collected in a rural Thai village. J Med Entomol. 1993;30:922–927. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/30.5.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrington LC, Scott TW, Lerdthusnee K. Dispersal of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti within and between rural communities. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halstead SB. Epidemiology. In: Halstead SB, editor. Dengue. Imperial College Press; London: 2008. pp. 75–122. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gubler DJ. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever: its history and resurgence as a global public health problem. In: Gubler DJ, Kuno G, editors. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. CAB International Press; Wallingford: 1997. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambrechts L, Scott TW, Gubler DJ. Consequences of the expanding global distribution of Aedes albopictus for dengue virus transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tatem AJ, Rogers DJ, Hay SI. Global transport networks and infectious disease spread. Adv Parasitol. 2006;62:293–343. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)62009-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tatem AJ, Rogers DJ, Hay SI. Estimating the malaria risk of African mosquito movement by air travel. Malar J. 2006;5:57. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell PF. The present status of malaria in the world. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1952;1:111–123. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1952.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell PF. World-wide malaria distribution, prevalence, and control. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1956;5:937–965. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1956.5.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lysenko AJ, Semashko IN. Geography of malaria: a medical-geographic study of an ancient disease. In: Medvedkov YV, editor. Medical geography. Academy of Sciences; Moscow: 1968. pp. 25–146. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guerra CA, Gikandi PW, Tatem AJ. The limits and intensity of Plasmodium falciparum transmission: implications for malaria control and elimination worldwide. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hay SI, Guerra CA, Gething PW. A world malaria map: Plasmodium falciparum endemicity in 2007. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hay SI, Okiro EA, Gething PW. Estimating the global clinical burden of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in 2007. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patil AP, Gething PW, Piel FB, Hay SI. Bayesian geostatistics in health cartography: the perspective of malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hales S, de Wet N, Maindonald J, Woodward A. Potential effect of population and climate changes on global distribution of dengue fever: an empirical model. Lancet. 2002;360:830–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09964-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jetten TH, Focks DA. Potential changes in the distribution of dengue transmission under climate warming. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:285–297. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beatty ME, Letson W, Edgil DM, Margolis HS. Estimating the total world population at risk for locally acquired dengue infection. Presented at the 56th annual meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; Philadelphia, PA, USA; Nov 4–8, 2007. Abstract 168.

- 34.Tran A, Deparis X, Dussart P. Dengue spatial and temporal patterns, French Guiana, 2001. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:615–621. doi: 10.3201/eid1004.030186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thai KTD, Nagelkerke N, Phuong HL. Geographical heterogeneity of dengue transmission in two villages in southern Vietnam. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:585–591. doi: 10.1017/S095026880999046X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mammen MP, Pimgate C, Koenraadt CJM. Spatial and temporal clustering of dengue virus transmission in Thai villages. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bejon P, Williams TN, Liljander A. Stable and unstable malaria hotspots in longitudinal cohort studies in Kenya. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hay SI, Smith DL, Snow RW. Measuring malaria endemicity from intense to interrupted transmission. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:369–378. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gething PW, Patil AP, Smith DL. A new world malaria map: Plasmodium falciparum endemicity in 2010. Malar J. 2011;10:378. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hay SI, Rogers DJ, Toomer JF, Snow RW. Annual Plasmodium falciparum entomological inoculation rates (EIR) across Africa: literature survey, Internet access and review. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90246-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith DL, McKenzie FE. Statics and dynamics of malaria infection in Anopheles mosquitoes. Malar J. 2004;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith DL, Dushoff J, Snow RW, Hay SI. The entomological inoculation rate and Plasmodium falciparum infection in African children. Nature. 2005;438:492–495. doi: 10.1038/nature04024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guerra CA, Hay SI, Lucioparedes LS. Assembling a global database of malaria parasite prevalence for the Malaria Atlas Project. Malar J. 2007;6:17. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith DL, Drakeley CJ, Chiyaka C, Hay SI. A quantitative analysis of transmission efficiency versus intensity for malaria. Nat Commun. 2010;1:108. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ha DQ. Dengue epidemic in southern Vietnam, 1998. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:422–425. doi: 10.3201/eid0604.000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beatty ME, Stone A, Fitzsimons DW. Best practices in dengue surveillance: a report from the Asia-Pacific and Americas dengue prevention boards. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guzmán MG, Kourí G. Dengue: an update. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(01)00171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huy R, Buchy P, Conan A. National dengue surveillance in Cambodia 1980–2008: epidemiological and virological trends and the impact of vector control. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:650–657. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.073908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simmons CP, Farrar JJ. Changing patterns of dengue epidemiology and implications for clinical management and vaccines. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ooi E-E. Dengue in Southeast Asia: epidemiological characteristics and strategic challenges in disease prevention. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;25:S115–S124. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009001300011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.San Martín JL, Brathwaite O, Zambrano B. The epidemiology of dengue in the Americas over the last three decades: a worrisome reality. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:128–135. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suaya JA, Shepard DS, Beatty ME. Dengue: burden of disease and costs of illness. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vong S, Khieu V, Glass O. Dengue incidence in urban and rural cambodia: results from population-based active fever surveillance, 2006–2008. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmidt W-P, Suzuki M, Dinh Thiem V. Population density, water supply, and the risk of dengue fever in Vietnam: cohort study and spatial analysis. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simmons CP, Farrar JJ, van Nguyen VC, Wills B. Dengue. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1423–1432. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1110265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Balmaseda A, Standish K, Mercado JC. Trends in patterns of dengue transmission over 4 years in a pediatric cohort study in Nicaragua. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:5–14. doi: 10.1086/648592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chau TNB, Hieu NT, Anders KL. Dengue virus infections and maternal antibody decay in a prospective birth cohort study of Vietnamese infants. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1893–1900. doi: 10.1086/648407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burke DS, Nisalak A, Johnson DE, Scott RM. A prospective study of dengue infections in Bangkok. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:172–180. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anderson KB, Chunsuttiwat S, Nisalak A. Burden of symptomatic dengue infection in children at primary school in Thailand: a prospective study. Lancet. 2007;369:1452–1459. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60671-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Endy TP, Chunsuttiwat S, Nisalak A. Epidemiology of inapparent and symptomatic acute dengue virus infection: a prospective study of primary school children in Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:40–51. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tien NTK, Luxemburger C, Toan NT. A prospective cohort study of dengue infection in schoolchildren in Long Xuyen, Viet Nam. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104:592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thai KTD, Nga TTT, Van Nam N. Incidence of primary dengue virus infections in Southern Vietnamese children and reactivity against other flaviviruses. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1553–1557. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Honório NA, Nogueira RMR, Codeço CT. Spatial evaluation and modeling of Dengue seroprevalence and vector density in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scott TW, Morrison AC. Vector dynamics and transmission of dengue virus: implications for dengue surveillance and prevention strategies. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;338:115–128. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-02215-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Focks DA, Barrera R. Dengue transmission dynamics: assessment and implications for control. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chow VT, Chan YC, Yong R. Monitoring of dengue viruses in field-caught Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes by a type-specific polymerase chain reaction and cycle sequencing. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:578–586. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scott TW, Morrison AC, Lorenz LH. Longitudinal studies of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in Thailand and Puerto Rico: population dynamics. J Med Entomol. 2000;37:77–88. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-37.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Snow RW, Omumbo JA, Lowe B. Relation between severe malaria morbidity in children and level of Plasmodium falciparum transmission in Africa. Lancet. 1997;349:1650–1654. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith DL, Guerra CA, Snow RW, Hay SI. Standardizing estimates of the Plasmodium falciparum parasite rate. Malar J. 2007;6:131. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hay SI, Okiro EA, Gething PW. Defining the relationship between Plasmodium falciparum parasite rate and clinical disease: statistical models for disease burden estimation. Malar J. 2009;8:186. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guzmán MG, Kouri G, Bravo J, Valdes L, Vazquez S, Halstead SB. Effect of age on outcome of secondary dengue 2 infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2002;6:118–124. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(02)90072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Egger JR, Coleman PG. Age and clinical dengue illness. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:924–925. doi: 10.3201/eid1306.070008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.WHO . Guidelines for the clinical evaluation of dengue vaccines in endemic areas. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wichmann O, Yoon I-K, Vong S. Dengue in Thailand and Cambodia: an assessment of the degree of underrecognized disease burden based on reported cases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Standish K, Kuan G, Avilés W, Balmaseda A, Harris E. High dengue case capture rate in four years of a cohort study in Nicaragua compared to national surveillance data. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Endy TP, Anderson KB, Nisalak A. Determinants of inapparent and symptomatic dengue infection in a prospective study of primary school children in Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tricou V, Minh NN, Van TP. A randomized controlled trial of chloroquine for the treatment of dengue in Vietnamese adults. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Duyen HTL, Ngoc TV, Ha DT. Kinetics of plasma viremia and soluble nonstructural protein 1 concentrations in dengue: differential effects according to serotype and immune status. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1292–1300. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nishiura H, Halstead SB. Natural history of dengue virus (DENV)-1 and DENV-4 infections: reanalysis of classic studies. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1007–1013. doi: 10.1086/511825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vaughn DW, Green S, Kalayanarooj S. Dengue viremia titer, antibody response pattern, and virus serotype correlate with disease severity. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:2–9. doi: 10.1086/315215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chanama S, Anantapreecha S, A-nuegoonpipat A, Sa-gnasang A, Kurane I, Sawanpanyalert P. Analysis of specific IgM responses in secondary dengue virus infections: levels and positive rates in comparison with primary infections. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tatem AJ, Smith DL, Gething PW, Kabaria CW, Snow RW, Hay SI. Ranking of elimination feasibility between malaria-endemic countries. Lancet. 2010;376:1579–1591. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61301-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Suaya JA, Shepard DS, Chang M-S. Cost-effectiveness of annual targeted larviciding campaigns in Cambodia against the dengue vector Aedes aegypti. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1026–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vu SN, Nguyen TY, Tran VP. Elimination of dengue by community programs using Mesocyclops (Copepoda) against Aedes aegypti in central Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vanlerberghe V, Toledo ME, Rodriguez M. Community involvement in dengue vector control: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2009;338:b1959. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kittayapong P, Yoksan S, Chansang U, Chansang C, Bhumiratana A. Suppression of dengue transmission by application of integrated vector control strategies at sero-positive GIS-based foci. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kourí G, Guzmán MG, Valdés L. Reemergence of dengue in Cuba: a 1997 epidemic in Santiago de Cuba. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:89–92. doi: 10.3201/eid0401.980111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gubler DJ, Clark GG. Community involvement in the control of Aedes aegypti. Acta Trop. 1996;61:169–179. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(95)00103-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Toledo ME, Rodriguez A, Valdés L. Evidence on impact of community-based environmental management on dengue transmission in Santiago de Cuba. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:744–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Parks W, Lloyd L. Planning social mobilization and communication for dengue fever prevention and control: a step-by-step guide. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ooi E-E, Goh K-T, Gubler DJ. Dengue prevention and 35 years of vector control in Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:887–893. doi: 10.3201/10.3201/eid1206.051210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Egger JR. Reconstructing historical changes in the force of infection of dengue fever in Singapore: implications for surveillance and control. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:187–196. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.040170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Esu E, Lenhart A, Smith L, Horstick O. Effectiveness of peridomestic space spraying with insecticide on dengue transmission; systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:619–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.WHO . Indoor residual spraying: use of indoor residual spraying for scaling up global malaria control and elimination. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vazquez-Prokopec GM, Kitron U, Montgomery B, Horne P, Ritchie SA. Quantifying the spatial dimension of dengue virus epidemic spread within a tropical urban environment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ritchie SA, Hanna JN, Hills SL. Dengue control in North Queensland, Australia: case recognition and selective indoor residual spraying. 2002. Available at: http://www.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/Dengue_Bulletin_Volume_26_Chap02.pdf (accessed Oct 2, 2012).

- 97.Nathan MB, Giglioli ME. Eradication of Aedes aegypti on Cayman Brac and Little Cayman, West Indies, with Abate (Temephos) in 1970–1971. Bull Pan Am Health Organ. 1982;16:28–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Giglioli G. An investigation of the house-frequenting habits of mosquitoes of the British Guiana coastland in relation to the use of DDT. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1948;28:43–70. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1948.s1-28.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kroeger A, Lenhart A, Ochoa M. Effective control of dengue vectors with curtains and water container covers treated with insecticide in Mexico and Venezuela: cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2006;332:1247–1252. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7552.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lenhart A, Orelus N, Maskill R, Alexander N, Streit T, McCall PJ. Insecticide-treated bednets to control dengue vectors: preliminary evidence from a controlled trial in Haiti. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:56–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Seng CM, Setha T, Nealon J, Chantha N, Socheat D, Nathan MB. The effect of long-lasting insecticidal water container covers on field populations of Aedes aegypti (L) mosquitoes in Cambodia. J Vector Ecol. 2008;33:333–341. doi: 10.3376/1081-1710-33.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.WHO . Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 2nd edn. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Thomas SJ, Endy TP. Critical issues in dengue vaccine development. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:442–450. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834a1b0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Crompton PD, Pierce SK, Miller LH. Advances and challenges in malaria vaccine development. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4168–4178. doi: 10.1172/JCI44423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Webster DP, Farrar JJ, Rowland-Jones S. Progress towards a dengue vaccine. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:678–687. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Whitehead SS, Blaney JE, Durbin AP, Murphy BR. Prospects for a dengue virus vaccine. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:518–528. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Leach A, Vekemans J, Lievens M. Design of a phase III multicenter trial to evaluate the efficacy of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in children across diverse transmission settings in Africa. Malar J. 2011;10:224. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Guy B, Barrere B, Malinowski C, Saville M, Teyssou R, Lang J. From research to phase III: preclinical, industrial and clinical development of the Sanofi Pasteur tetravalent dengue vaccine. Vaccine. 2011;29:7229–7241. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.The RTSS Clinical Trials Partnership First results of phase 3 trial of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in African children. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yekutiel P. The Global Malaria Eradication Campaign. In: Klingberg MA, editor. Eradication of infectious diseases: a critical study. Karger; Basel: 1980. pp. 34–88. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wernsdorfer W, Hay SI, Shanks GD. Learning from history. In: Feachem RGA, Phillips AA, Targett GA, editors. Shrinking the malaria map: a prospectus on malaria elimination. Malaria Elimination Group; San Francisco: 2009. pp. 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nájera JA, González-Silva M, Alonso PL. Some lessons for the future from the Global Malaria Eradication Programme (1955–1969) PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Soper FL. The 1964 status of Aedes aegypti eradication and yellow fever in the Americas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1965;14:888–891. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1965.14.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Carmago S. History of Aedes aegypti eradication in the Americas. Bull World Health Organ. 1967;36:602–603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.PAHO The feasibility of eradicating Aedes aegypti in the Americas. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1997;1:68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Halstead SB. Successes and failures in dengue control: global experience. 2000. Available at: http://www.searo.who.int/en/Section10/Section332/Section522_2509.htm (accessed Oct 2, 2012).

- 117.Soper FL. The prospects for Aedes aegypti eradication in Asia in the light of its eradication in Brazil. Bull World Health Organ. 1967;36:645–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Snow RW, Okiro EA, Gething PW, Atun R, Hay SI. Equity and adequacy of international donor assistance for global malaria control: an analysis of populations at risk and external funding commitments. Lancet. 2010;376:1409–1416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61340-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.DeRoeck D, Deen J, Clemens JD. Policymakers' views on dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever and the need for dengue vaccines in four southeast Asian countries. Vaccine. 2003;22:121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Morrison AC, Zielinski-Gutierrez E, Scott TW, Rosenberg R. Defining challenges and proposing solutions for control of the virus vector Aedes aegypti. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e68. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Eisen L, Beaty BJ, Morrison AC, Scott TW. Proactive vector control strategies and improved monitoring and evaluation practices for dengue prevention. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:1245–1255. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Walker T, Johnson PH, Moreira LA. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature. 2011;476:450–453. doi: 10.1038/nature10355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Snow RW, Guerra CA, Mutheu JJ, Hay SI. International funding for malaria control in relation to populations at risk of stable Plasmodium falciparum transmission. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]