Abstract

Early-onset preeclampsia (EPE) is a severe form of preeclampsia that involves life-threatening neurological complications. However, the underlying mechanism by which EPE affects the maternal brain is not known. We hypothesized that plasma from women with EPE increases blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability vs. plasma from women with late-onset preeclampsia (LPE) or normal pregnancy (NP) and investigated its underlying mechanism by perfusing cerebral veins from nonpregnant rats (n=6–7/group) with human plasma from women with EPE, LPE, or NP and measuring permeability. We show that plasma from women with EPE significantly increased BBB permeability vs. plasma from women with LPE or NP (P<0.001). BBB disruption in response to EPE plasma was due to a 260% increase of circulating oxidized LDL (oxLDL) binding to its receptor, LOX-1, and subsequent generation of peroxynitrite (P<0.001). A rat model with pathologically high lipid levels in pregnancy showed symptoms of preeclampsia, including elevated blood pressure, growth-restricted fetuses, and LOX-1-dependent BBB disruption, similar to EPE (P<0.05). Thus, we have identified LOX-1 activation by oxLDL and subsequent peroxynitrite generation as a novel mechanism by which disruption of the BBB occurs in EPE. As increased BBB permeability is a primary means by which seizure and other neurological symptoms ensue, our findings highlight oxLDL, LOX-1, and peroxynitrite as important therapeutic targets in EPE.—Schreurs, M. P. H., Hubel, C. A., Bernstein, I. M., Jeyabalan, A., and Cipolla, M. J. Increased oxidized low-density lipoprotein causes blood-brain barrier disruption in early-onset preeclampsia through LOX-1.

Keywords: pregnancy, peroxynitrite, vascular permeability, neurological complications

Neurological symptoms are the most serious and life-threatening complication of preeclampsia (1). The new onset of uncontrolled vomiting, cortical blindness, seizure, and coma during preeclampsia represent a severe form of disease that accounts for ∼75% of all maternal deaths worldwide (2, 3). Epidemiologic studies have shown that neurological complications occur more often in early-onset preeclampsia (EPE), in which hypertension and proteinuria occur before 34 wk of gestation, compared to late-onset preeclampsia (LPE), in which hypertension and proteinuria develop after 34 wk of gestation (4–6). Notably, this suggests that EPE is a more severe form of preeclampsia that adversely affects the maternal brain, promoting neurological complications. However, the unique factors contributing to neurological involvement during EPE are largely unknown.

Vasogenic brain edema has been shown in preeclampsia and is the result of disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and increased cerebrovascular permeability (7–9). In addition to brain edema, increased BBB permeability promotes the passage of damaging proteins and plasma constituents into the brain parenchyma that can activate microglia and promote seizure activity (8, 10, 11). Thus, the BBB has a central role in promoting neurological symptoms during preeclampsia. We previously showed that plasma from women with preeclampsia, but not from women with normal pregnancy (NP), increased BBB permeability of cerebral veins, demonstrating that circulating factors are an important means by which BBB disruption can occur in preeclampsia (12). In that study, plasma was pooled from women with severe preeclampsia; however, EPE and LPE were not distinguished. The first aim of this study was to investigate the differential effect of circulating factors in plasma from EPE and LPE plasma on BBB permeability. We hypothesized that circulating factors in plasma from women with EPE would have a greater effect on BBB disruption that underlies neurological symptoms in that group.

One circulating factor that is increased in preeclampsia compared to normal pregnancy is oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL; refs. 13–15). Increased oxidative stress in the placental circulation during preeclampsia causes oxidative conversion of LDL to oxLDL (16, 17). OxLDL has a greater negative charge compared to native LDL and, therefore, selectively binds lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX-1), expressed predominantly on endothelial cells, to cause vascular dysfunction in several disease states, including hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis (18, 19). Thus, our second aim of this study was to investigate oxLDL and LOX-1 activation as an underlying mechanism by which EPE plasma possibly selectively causes the BBB to be more permeable. To our knowledge, no study has shown that circulating oxLDL and LOX-1 activation is an underlying cause of BBB disruption in preeclampsia. However, understanding this mechanism would be particularly important in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia, considering recent reports of increased LOX-1 expression in the systemic vasculature from women with preeclampsia and in a rat model of preeclampsia (20–22).

LOX-1 activation rapidly stimulates the production of superoxide in endothelial cells, mainly through activation of NADPH oxidase (23, 24). Superoxide decreases the concentration of nitric oxide (NO) by binding NO to form peroxynitrite, a relatively stable reactive oxygen and nitrogen species that has deleterious effects on cell viability and endothelial function (25). Peroxynitrite generation has been reported in the maternal systemic vasculature and is thought to contribute to endothelial dysfunction during preeclampsia. However, whether peroxynitrite generation, secondary to LOX-1 activation, is also involved in disrupting the BBB during preeclampsia is not known. Thus, our last aim of the study was to determine whether increased levels of circulating oxLDL in plasma from women diagnosed with EPE would activate LOX-1, resulting in subsequent peroxynitrite generation leading to BBB disruption in women with EPE. In this study, we used an established method of measuring BBB permeability of cerebral veins perfused with plasma (12, 26, 27). Cerebral veins are used because they have BBB properties and are a major site of disruption during acute hypertension (26–28).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Maternal plasma samples were obtained from an ongoing investigation of preeclampsia [Prenatal Exposures and Preeclampsia Prevention (PEPP)] at the Magee-Womens Research Institute and Hospital (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). PEPP was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The PEPP committee approved the use of these previously frozen samples by our institution and deidentified clinical data. Blood samples from all women were collected into EDTA tubes. Plasma was centrifuged at 1600 rpm and portioned into aliquots. Plasma was then pooled from 4 groups: nonpregnant (NonP), women who had never been pregnant (n=9); NP (n=12); LPE (n=10); and EPE (n=5) and stored at −80°C until experimentation. The women enrolled in the preeclampsia groups met the criteria according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg systolic and/or 90 mmHg diastolic plus an increase of >30 mmHg systolic and/or 15 mmHg diastolic plus proteinuria > 300 mg/24 h or ≥ 2+ protein using a urine dipstick test. Women with EPE were diagnosed with preeclampsia and delivered before 34 wk of gestation, and women with LPE were diagnosed and delivered after 34 wk of gestation (see Table 1). Only nonsmokers and nulliparous women were included.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Parameter | NonP | NP | LPE | EPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 12 | 10 | 5 |

| Age (yr) | 25.4 ± 4.6 | 26.0 ± 4.5 | 31.0 ± 3.6 | 25.0 ± 5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 ± 3.2 | 26.4 ± 3.7 | 26.5 ± 7.4 | 24.3 ± 3.0 |

| GA sample (wk) | 34.9 ± 1.8 | 35.8 ± 1.6 | 32.3 ± 1.6 | |

| GA delivery (wk) | 40.1 ± 0.9 | 36.0 ± 1.4 | 32.5 ± 1.4 | |

| SBP <20 wk gestation (mmHg) | 107.0 ± 6.8 | 110.1 ± 7.2 | 119.5 ± 12.4 | 122.0 ± 5.6 |

| DBP <20 wk gestation (mmHg) | 65.5 ± 5.5 | 66.8 ± 3.9 | 73.0 ± 7.3 | 73.0 ± 4.0 |

| SBP at time delivery (mmHg) | 119.4 ± 7.3 | 152.4 ± 8.6 | 160.0 ± 9.5 | |

| DBP at time delivery (mmHg) | 68.8 ± 11.7 | 91.7 ± 6.4 | 100.6 ± 11.0 | |

| Birthweight (g) | 3601 ± 380 | 2271 ± 143 | 1462 ± 223 | |

| Birthweight centile (%) | 56.1 ± 7.1 | 18.9 ± 4.9 | 7.6 ± 1.8 |

NonP, nonpregnant; NP, normal pregnancy; LPE, late-onset preeclampsia; EPE, early-onset preeclampsia; GA, gestational age; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BMI, body mass index.

Measurement of oxLDL in human plasma samples

The levels of oxLDL in the plasma from the NonP, NP, LPE, and EPE groups were determined using a sandwich ELISA kit (Immunodiagnostik, Bensheim, Germany), according to the manufacturers' instructions. Measurements were performed in duplicate and were averaged.

Animals

Female Sprague-Dawley virgin nonpregnant rats (12–14 wk; 250–300 g) or female Sprague-Dawley pregnant rats (d 5; 12–14 wk, 250–300 g) were purchased from Charles River (Saint-Constant, QB, Canada). Animals were housed in the animal care facility, an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited facility. Animals had access to food and water ad libitum and were maintained on a 12-h light-dark cycle. The animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Vermont and complied with the U.S. National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

High-cholesterol rat model

On d 6 of pregnancy, rats were divided into a late-pregnancy control (LP-CTL) group (n=8) and a late-pregnancy, high-cholesterol (LP-HC) treatment group (n=8). The LP-CTL group received Prolab 3000 rodent chow (PMI Nutrition International, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 14 d. The LP-HC group received a 14-d diet consisting of Prolab 3000 rodent chow, including 2% cholesterol and 0.5% cholic acid (added to lower hepatic clearance of cholesterol) to increase total and LDL-cholesterol. Experimentation was done on d 14 of the diet, which equaled d 20 of pregnancy in all animals. Pups and placentas were weight averaged per animal.

Blood pressure measurements

All LP-CTL and LP-HC animals had blood pressure measurements taken on d 2 and d 13 of dietary treatment. Animals were trained for 2 d prior to the first day of blood pressure measurements to make the rats familiar with handling and restraint associated with the procedure and thereby avoid measuring artificially high blood pressures. Blood pressure was taken using a noninvasive tail-cuff method (CODAS 8; Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT, USA). Briefly, animals were placed in individual holders on a heating plate, and both an occlusion cuff and a volume pressure-recording cuff were placed on the tail close to the base. Animals were warmed to 30°C for optimal volume pressure recording. Systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressure; heart pulse rate; tail blood volume; and tail blood flow were measured simultaneously.

Rat plasma samples

Plasma samples were obtained from trunk blood from LP-CTL and LP-HC rats. Plasma was collected in EDTA plasma separation tubes and was centrifuged for 10 min at 2500 rpm. Plasma was then aliquoted and directly used for permeability experiments.

BBB permeability measurements

The first set of experiments was performed to determine the effects of circulating factors in plasma from women in the EPE and LPE groups on BBB permeability compared to the NP and NonP groups. We measured Lp, the critical transport parameter that relates water flux to hydrostatic pressure, in isolated cerebral veins from nonpregnant female rats after perfusing with plasma from 1 of the 4 groups of women, as described previously (26). This method of measuring BBB permeability was specifically developed to have a direct measure of water permeability and has been successfully used in several previous studies (12, 26, 27). The vein of Galen was used for all permeability experiments as representation of the BBB because this vein has BBB properties and is where BBB disruption occurs first during acute hypertension (28). Further, only veins from nonpregnant rats were used to isolate the possible effects of circulating factors in the plasma, and our previous studies have shown no difference in BBB permeability comparing vessels from nonpregnant and pregnant rats (27). Briefly, cerebral veins were carefully dissected out of the brain of nonpregnant rats, and each proximal end was mounted on one glass cannula in an arteriograph chamber. Veins were perfused intraluminally with 20% v/v plasma from either the NonP (n=7), NP (n=7), LPE (n=6), or EPE (n=6) group in a HEPES buffer for 3 h at 10 ± 0.3 mmHg and 37°C. The distal end of the vessel was tied off with a nylon suture. After this incubation period with plasma, intravascular pressure was increased to 25 ± 0.1 mmHg, and the drop in pressure due to transvascular filtration of water out of the vessel in response to hydrostatic pressure was measured for 40 min. The decrease of intravascular pressure per minute (mmHg/min) was converted to volume flux across the vessel wall (μm3) using a conversion curve, as described previously (26). After flux was determined, transvascular filtration per surface area (Jv/S) and Lp were calculated by normalizing flux to the surface area and oncotic pressure of the plasma perfusate, which was determined by a commercially available oncometer.

In a separate set of experiments, we determined the involvement of LOX-1 activation on BBB permeability by adding a neutralizing antibody to LOX-1 (5 μg/ml; n=6) to the plasma from women with EPE before perfusing the plasma into the vein of Galen, and the permeability experiment was repeated. Because we already showed that the presence of control goat IgG (also used as a control for this antibody) perfused with plasma in the cannula did not interfere with the permeability measurements (27), we did not repeat these control IgG experiments in the current study.

Another set of experiments was performed to determine the involvement of peroxynitrite generation in plasma from women with EPE by adding the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst FeTMPyP (50 μM; n=6) to the plasma from women with EPE before perfusing the plasma in the cerebral veins. FeTMPyP is a ferric-porphyrin-complex that catalytically isomerizes peroxynitrite to nitrate in vitro and has been shown to be selective for blocking peroxynitrite effects without interfering with NO or superoxide (29). Therefore, FeTMPyP serves as a selective peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst. In addition, the concentration of 50 μM was based on one of our earlier studies where FeTMPyP was used in isolated arteries to scavenge peroxynitrite (30).

A separate set of experiments was performed to determine the effects of exogenous oxLDL on BBB permeability by the addition of exogenous human oxLDL (3.5 μg/ml; n=7) to plasma from women in the NonP group before perfusing the plasma in the cerebral veins. For these experiments, plasma from the NonP group was chosen rather than plasma from the NP group to eliminate other possible circulating factors present in pregnancy that could interact with oxLDL. To determine whether there was a causal link between oxLDL increasing BBB permeability and peroxynitrite generation, we repeated these experiments with the addition of FeTMPyP (50 μM; n=6) to the oxLDL-plasma mixture before perfusion in the vein of Galen and measured Lp.

The last set of experiments was performed to determine the involvement of high levels of cholesterol in pregnancy on pregnancy outcome and BBB disruption. The cerebral vein of Galen of LP rats that received either a control diet or a high-cholesterol diet was used for the permeability experiments as described above. For these experiments, 20% v/v plasma in HEPES buffer was taken and perfused in veins from the same animals. To determine the contribution of oxLDL in increasing BBB permeability in the high-cholesterol-treated pregnant rats, the same neutralizing LOX-1 antibody (5 μg/ml; n=8) was added to the plasma from the LP-HC animals before perfusion in the cerebral veins.

Measurement of mRNA expression of LOX-1 using real-time quantitative PCR

The middle cerebral artery (MCA) was used as a representative cerebral vessel to measure mRNA expression of LOX-1 in the LP-CTL (n=6) and LP-HC (n=7) animals, as the vein of Galen was used for permeability experiments in these animals. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed as described previously (31). The quantitative PCR primer for the rat transcripts for LOX-1 was LOX-1 (forward), -GATGATCTGAACTTCGTCTTACAAGC- and (reverse), -TCAGCAAACACAACTCCTCCTT-.

Drugs and solutions

HEPES physiological salt solution was made fresh daily and consisted of (mM): 142.00 NaCl, 4.70 KCl, 1.71 MgSO4, 0.50 EDTA, 2.80 CaCl2, 10.00 HEPES, 1.20 KH2PO4, and 5.00 dextrose. FeTMPyP was purchased from Calbiochem, (Gibbstown, NJ, USA; cat. no. 341501). LOX-1 antibody was purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA; AF1564). Highly oxidized LDL was purchased from Kalen Biomedical LLC (Montgomery Village, MN, USA; 770252-7).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± se. Analyses were performed by 1-way ANOVA with a post hoc Newman Keuls test for multiple comparisons where appropriate or with a Student's t test. Differences were considered statistically significant at values of P < 0.05. mRNA expression of LOX-1 was determined by quantitative PCR and calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

RESULTS

Patients with EPE have worse pregnancy outcome compared to LPE and NP groups

Although the pathogenesis of preeclampsia is not clear, it is accepted that the pathological release of soluble factors from the ischemic placenta into the maternal circulation causes endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and the symptoms of hypertension and proteinuria (16). Thus, it is reasonable to examine maternal blood as a source of circulating factors that might also be affecting the cerebral endothelium to cause BBB disruption and promote neurological symptoms.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients from whom plasma samples were obtained. There were no significant differences between the 4 groups of women with respect to age or BMI. Blood pressure measured in early gestation before 20 wk of pregnancy was similar in all pregnancy groups and was comparable to the blood pressure measured in the group of women who had never been pregnant. These results are consistent with the symptoms of preeclampsia developing after 20 wk of gestation, including hypertension.

At time of delivery, both systolic and diastolic blood pressure measured in women in the NP group were similar to the blood pressure measured before 20 wk of gestation. However, blood pressure of both preeclampsia groups was significantly increased and met the diagnostic criteria of preeclampsia. Although blood pressure at time of delivery was higher in the EPE group compared to the LPE group, this was not significantly different. Further, all women in the NP group delivered after 37 wk of gestation. Women with LPE delivered after 34 wk but before 37 wk of gestation, and women with EPE were diagnosed and delivered before 34 wk of gestation, in accordance with the definition of EPE. Lastly, the infants born to women with EPE had the lowest infant birth weight compared to the other groups of pregnant women. Notably, only women with EPE delivered babies with intrauterine growth restriction (<10th percentile) compared to the LPE and NP groups (>10th percentile). Thus, women with EPE that were diagnosed and delivered before 34 wk of gestation from whom plasma was taken had a more severe form of preeclampsia compared to the LPE group.

Plasma from women with EPE significantly increases BBB permeability compared to plasma from LPE and NP groups

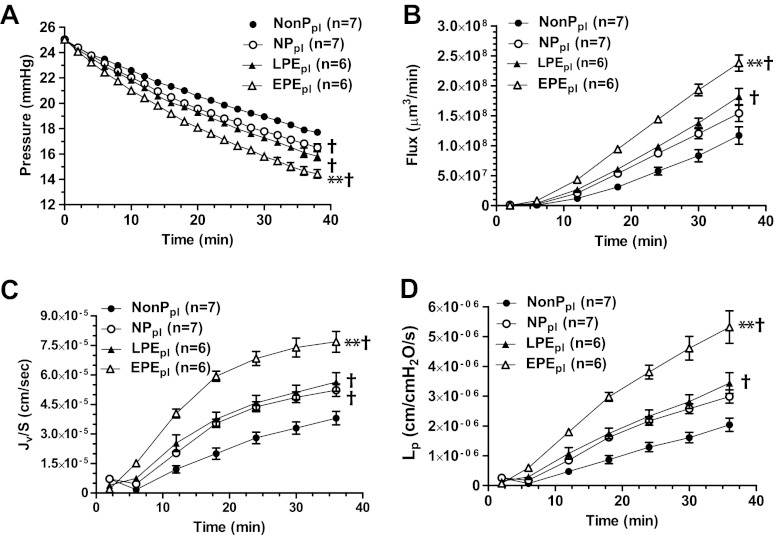

Epidemiologic studies suggest that women with EPE develop neurological complications more often compared to women with LPE (4, 5). Because the BBB has a central role in the development of neurological symptoms such as seizure (8, 10, 32), we measured BBB permeability in cerebral veins perfused with 20% v/v plasma from women in the NP, LPE, or EPE group. Permeability in response to plasma from the NonP group was used as a control. Several permeability parameters were measured in vitro in response to a 3-h exposure to plasma, including filtration pressure drop, volume flux, Jv/S, and Lp. As shown in Fig. 1, exposure to plasma from the NP group caused an increase in intravascular pressure drop and Jv/S, but not in volume flux or Lp. However, in both preeclampsia groups, all permeability parameters were significantly increased compared to the NonP group. Notably, the increase in permeability in response to LPE plasma was similar to NP plasma, whereas EPE plasma caused a significant increase in permeability compared to all other groups, including LPE plasma. These results demonstrate that circulating factors present in plasma from women with EPE disrupt the BBB and may relate to the propensity for neurological complications to occur in that group of patients with preeclampsia.

Figure 1.

Plasma from women with EPE increases BBB permeability compared to plasma from women in the LPE or NP groups. The permeability parameters intravascular pressure drop, volume flux, Jv/S, and Lp were used to determine BBB permeability in cerebral veins from nonpregnant rats in response to plasma from women in the EPE, LPE, NP, and NonP groups. A) Decrease in intravascular pressure in response to plasma from EPE, LPE, and NP groups was significantly greater compared to NonP group. Notably, the decrease in intravascular pressure was significantly greater in women with EPE compared to all other groups, including women with LPE. B) Plasma from both preeclampsia groups showed a significant increase in flux compared to plasma from NonP group. Plasma from women with EPE caused a significantly greater flux compared to all other groups. C) Plasma from EPE, LPE, and NP groups caused a significant increase in Jv/S compared to plasma from NonP group, and only plasma from women with EPE significantly increased Jv/S compared to all other groups. D) Plasma from both preeclampsia groups significantly increased Lp compared to NonP group, and only plasma from women with EPE significantly increased Lp compared to all other groups. **P < 0.01 vs. all other groups; †P < 0.01 vs. NonP.

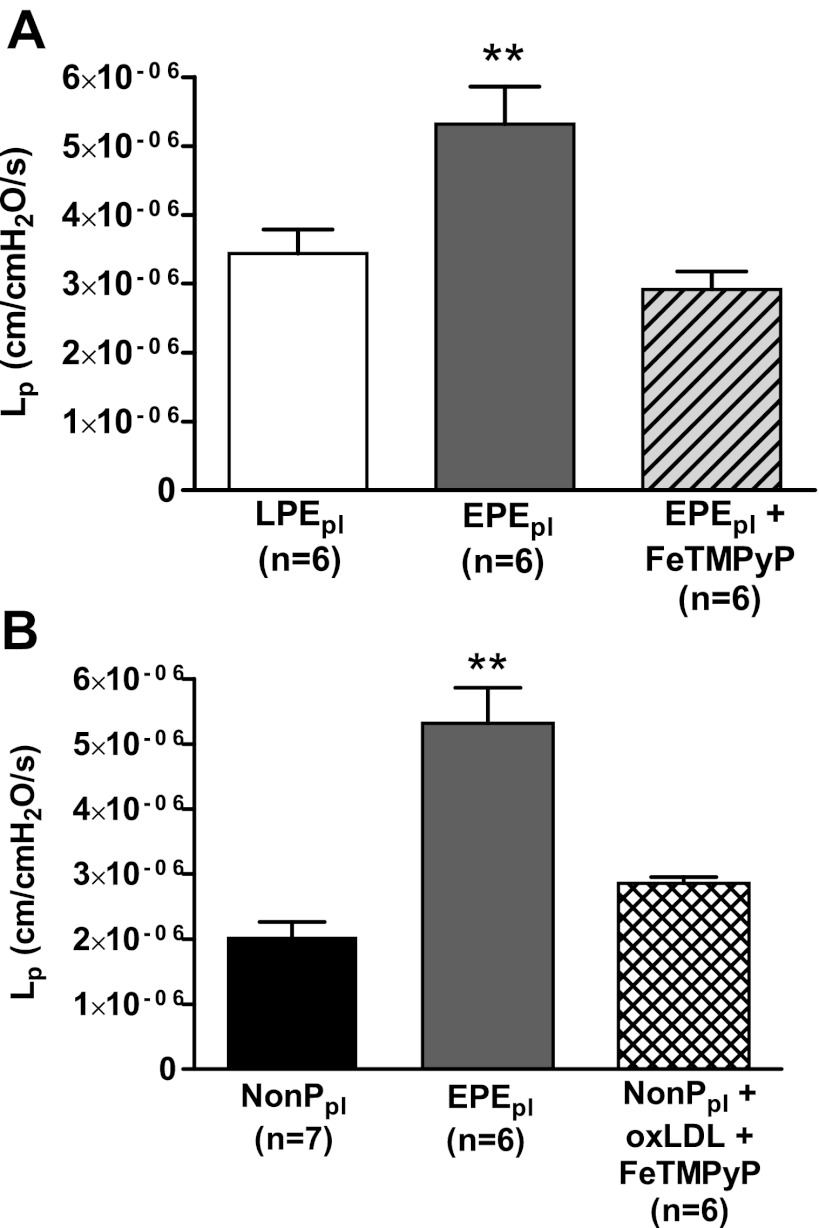

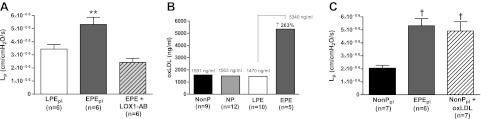

Inhibition of LOX-1 activation prevents increased BBB permeability induced by EPE plasma

Circulating oxLDL binds its receptor LOX-1 to cause oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in many pathological states, such as atherosclerosis, diabetes, and hypertension (18, 33). To determine whether LOX-1 activation is involved in increasing BBB permeability in response to acute exposure of plasma from women with EPE, we neutralized LOX-1 with an antibody to inhibit its activation prior to perfusion with EPE plasma and measurement of permeability. Inhibition of LOX-1 abolished the increased BBB permeability induced by circulating factors in this plasma (Fig. 2A). Thus, LOX-1 activation is involved in increasing BBB permeability in plasma from women with EPE.

Figure 2.

Increased levels of oxLDL in plasma from women with EPE women are responsible for the significant increased BBB permeability. A) BBB permeability in response to plasma from women with LPE, women with EPE, and women with EPE with the addition of 5 μg/ml of a neutralizing LOX-1 antibody. LOX-1 antibody inhibited the increased BBB permeability induced by plasma from women with EPE. B) OxLDL levels in plasma from women with EPE compared to LPE, NP and NonP groups. Plasma from women with EPE women had a 260% increase in oxLDL compared to plasma from women with LPE. C) Lp as a measure of BBB permeability in cerebral veins from nonpregnant rats in response to plasma from women in the NonP and EPE groups and NonP plasma with addition of 3.5 μg/ml exogenous oxLDL. Exogenous oxLDL significantly increased BBB permeability to the same levels as plasma from women with EPE. **P < 0.01 vs. all other groups; †P < 0.01 vs. NonP.

To determine whether oxLDL was increased in plasma from women with EPE that was responsible for the LOX-1-induced increase in BBB permeability, we measured oxLDL levels in the plasma from all 4 groups of women by ELISA. Plasma from women with EPE had a 260% increase in oxLDL levels compared to plasma from women with LPE (Fig. 2B). The levels of oxLDL in plasma from the NonP, NP, and LPE groups were comparable.

We next confirmed that oxLDL was capable of increasing BBB permeability without the presence of other circulating factors present in the plasma from women with EPE by adding 3.5 μg/ml of purified human oxLDL in plasma from the NonP group and measuring permeability. This concentration of oxLDL was used based on the values in the EPE plasma measured by ELISA. The addition of exogenous oxLDL to plasma from the NonP group caused a significant increase in BBB permeability that was comparable to what was seen with plasma from women with EPE (Fig. 2C). To our knowledge, this is the first report that suggests that high levels of oxLDL present in plasma from women with EPE is the circulating factor responsible for the increase in BBB permeability in response to that plasma by activation of LOX-1.

Peroxynitrite decomposition with FeTMPyP prevents increased BBB permeability induced by EPE plasma and oxLDL

Activation of LOX-1 leads to increased production of superoxide through NADPH oxidase, which rapidly binds NO to form peroxynitrite (23). To determine whether peroxynitrite generation in response to LOX-1 activation by oxLDL is responsible for increased BBB permeability, we perfused cerebral veins with plasma from women with EPE plus 50 μM FeTMPyP, a selective peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst, prior to measuring permeability. FeTMPyP significantly inhibited the increase in BBB permeability caused by EPE plasma (Fig. 3A). This result demonstrates that peroxynitrite generation is involved in BBB disruption with exposure to EPE plasma. We next confirmed that the increase in BBB permeability caused by exogenous oxLDL was due to increased generation of peroxynitrite by adding 50 μM FeTMPyP to NonP plasma with exogenous oxLDL. Peroxynitrite decomposition with FeTMPyP inhibited the increase in BBB permeability induced by oxLDL (Fig. 3B). Together, these results demonstrate that peroxynitrite generation is induced by oxLDL and is the underlying mechanism by which BBB permeability is increased.

Figure 3.

oxLDL-induced increase in BBB permeability in women with EPE is prevented by the peroxynitrite scavenger FeTMPyP. A) Hydraulic conductivity LP at 36 min as a measure of BBB permeability in cerebral veins of nonpregnant rats in response to plasma from women with LPE and plasma from women with EPE with and without the addition of 50 μM FeTMPyP. FeTMPyP inhibited the BBB permeability induced by plasma from women with EPE. B) Lp as a measure of BBB permeability in response to untreated plasma from women in the NonP and EPE groups, and in response to plasma from NonP women plus 3.5 μg/ml oxLDL and 50 μM FeTMPyP. FeTMPyP inhibited the BBB permeability induced by 3.5 μg/ml exogenous oxLDL in plasma from NonP women. **P < 0.01 vs. all other groups.

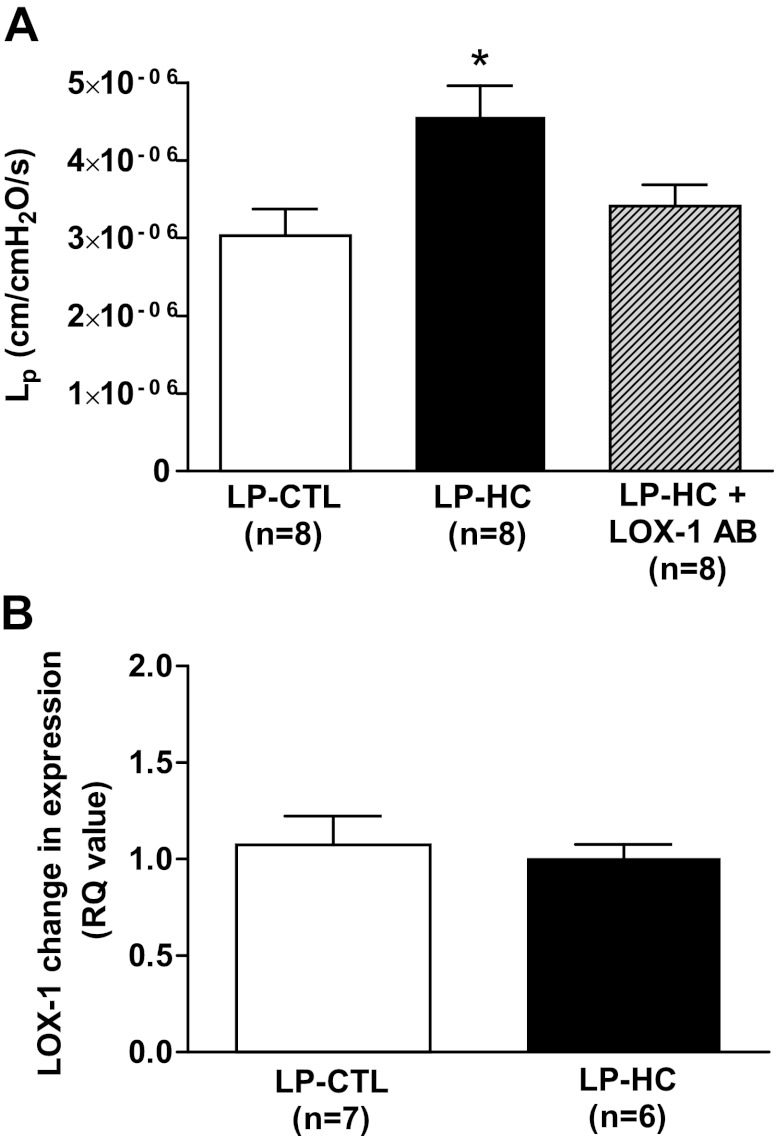

Pathologically high lipid levels during pregnancy in rats cause preeclampsia-like symptoms and LOX-1-dependent BBB disruption

Preeclampsia has been associated with high levels of LDL (13, 34). In addition, preeclampsia is a state of increased oxidative stress in the placental circulation, which causes oxidative conversion of LDL to oxLDL, resulting in increased circulating levels of oxLDL in preeclampsia (16, 17). Because we found high levels of oxLDL in plasma from women with EPE that caused disruption of the BBB, we wanted to determine its effects in vivo by creating a rat model with pathologically high levels of LDL during pregnancy. Rats in the LP-HC group had a 350% increase in cholesterol compared to LP-CTL rats fed a normal diet, including a significant increase in LDL cholesterol (data not shown). Table 2 shows that LP-HC rats had a worse pregnancy outcome compared to LP-CTL rats, with similar characteristics as seen in women with EPE. LP-HC rats had significantly higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures compared to LP-CTL rats and also had a worse pregnancy outcome, including a significantly smaller number of pups and a higher rate of reabsorptions. Further, LP-HC rats had growth-restricted fetuses, with pup weights that were significantly lower compared to the LP-CTL group.

Table 2.

Pregnancy outcome of LP-HC compared to LP-CTL rats

| Parameter | LP-CTL | LP-HC |

|---|---|---|

| n | 8 | 8 |

| Weight (g) | 408 ± 6 | 403 ± 10 |

| SBP at d 13 of diet (mmHg) | 118 ± 2 | 126 ± 2* |

| DBP at d 13 of diet (mmHg) | 87 ± 2 | 94 ± 2* |

| Pups (n) | 16 ± 0.5 | 12 ± 0.6* |

| Resorptions (n) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| Avg. pup weight (g) | 2.42 ± 0.06 | 2.12 ± 0.04* |

| Avg. placenta weight (g) | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 0.48 ± 0.01* |

LP-CTL, late-pregnancy control; LP-HC, late-pregnancy high cholesterol; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; avg., average.

P < 0.05 vs. LP-CTL.

Next, we investigated whether pathologically high levels of LDL in pregnant rats led to increased BBB permeability that was dependent on LOX-1 activation, as we have also shown in women with EPE. Figure 4A shows that cerebral veins from LP-HC rats perfused with plasma from the same animals had increased BBB permeability compared to control animals that was abolished by addition of the LOX-1 antibody. These results suggest that oxLDL is responsible for increasing BBB permeability in the LP-HC animals, similar to EPE. Because oxLDL and not native LDL binds to LOX-1 (24), these results also confirm that pathologically high levels of LDL in pregnancy lead to high levels of oxLDL.

Figure 4.

Pathologically high levels of lipids in pregnant rats evoke symptoms of preeclampsia and also lead to LOX-1-mediated increased BBB permeability. A) Hydraulic conductivity (Lp) as a measure of BBB permeability at 36 min in cerebral veins from LP-CTL rats in response to LP-CTL plasma and from LP-HC rats in response to LP-HC plasma with and without the addition of 5 μg/ml LOX-1 antibody. LP-HC rats showed a significant increase in BBB permeability that could be inhibited with the addition of LOX-1 antibody. B) mRNA expression of LOX-1 in cerebral veins from LP-CTL and LP-HC rats. There was no difference in mRNA expression of LOX-1 in cerebral veins from LP-HC vs. LP-CL rats. *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups.

Lastly, because the pregnant rats were exposed to high levels of cholesterol during their entire pregnancy, we wanted to determine whether LOX-1 expression was increased in the cerebral circulation that could cause the increased BBB permeability. Recent studies showed increased LOX-1 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) after 24-h incubation with preeclamptic plasma (21) and in a rat model of preeclampsia (20). To determine whether LOX-1 mRNA expression was increased in the cerebral vasculature from LP-HC animals, we isolated the MCAs from the same animals used for permeability experiments and measured mRNA expression of LOX-1. mRNA expression of LOX-1 was similar in the LP-HC and LP-CTL animals (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the mechanism of increased BBB permeability in the LP-HC animals was due to circulating oxLDL activating LOX-1 as opposed to up-regulation of LOX-1 in the cerebral endothelium.

DISCUSSION

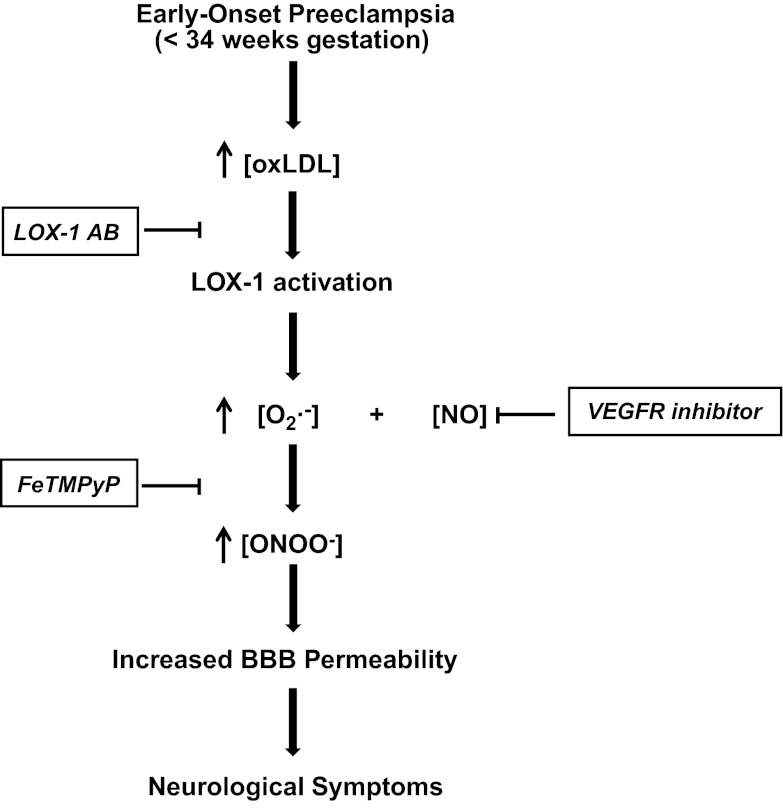

In the present study, we provide new direct evidence for a different etiology between EPE and LPE and reveal a novel mechanism that is responsible for BBB disruption in women with EPE. Circulating factors in plasma from women with EPE significantly increased BBB permeability compared to women in the LPE or NP groups. The increased BBB permeability was prevented by inhibiting LOX-1 and was confirmed in vivo in pregnant rats with pathologically high levels of LDL that also showed LOX-1-dependent increased BBB permeability. Circulating oxLDL, a major ligand of LOX-1, was significantly increased in plasma from women with EPE compared to the LPE or NP groups. In addition, exogenous oxLDL in plasma from the NonP group increased BBB permeability comparable to EPE. Further, the selective peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst FeTMPyP inhibited the increased BBB permeability induced by plasma from women with EPE or by exogenous oxLDL. Thus, our results show for the first time that increased circulating oxLDL present in plasma from women with EPE significantly increases BBB permeability through LOX-1 activation and subsequent increased peroxynitrite generation (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic showing the proposed mechanism leading to BBB disruption and neurological complications in EPE. Women with EPE have a more severe form of disease that is associated with increased levels of circulating oxLDL. The increased circulating levels of oxLDL in plasma from women with EPE bind to their receptor LOX-1 on the cerebral endothelium that comprises the BBB. LOX-1 activation leads to generation of peroxynitrite (ONOO−), most likely through increased production of superoxide (O2·−), causing BBB disruption and increased BBB permeability that is responsible for neurological complications in preeclampsia.

The cerebral endothelium that comprises the BBB has unique features compared to endothelium outside the CNS, including high electrical resistance tight junctions, and a lack of fenestrations that results in low hydraulic conductivity (35). Disruption of the BBB is accompanied by increased BBB permeability and subsequent vasogenic edema resulting in neurological symptoms (7–9). Preeclampsia, a hypertensive disorder unique to pregnancy, can be complicated with life-threatening neurological symptoms, including cerebral edema, hemorrhage, and seizure, that are associated with increased BBB permeability (1, 7, 8). As we have previously shown, increased BBB permeability in severe preeclampsia is caused by a pathological release of circulating factors into the maternal circulation that can cause BBB breakdown (12). Here, we demonstrated for the first time that intraluminal exposure of cerebral veins to plasma from women with EPE for 3 h significantly increased BBB permeability compared to plasma from LPE or NP groups. These new findings point to the acute effect of circulating factors in plasma from women with EPE on BBB permeability after a short exposure time. Also, these results directly strengthen the evidence that EPE and LPE have different etiologies, arising from greater placental underperfusion and subsequent release of circulating factors in EPE compared to LPE (4). To our knowledge, no studies have differentiated effects of circulating factors in LPE compared to EPE on BBB permeability. Only one report found increased permeability in mesenteric arteries from frogs in response to plasma from women with severe compared to mild preeclampsia, where the severity of preeclampsia was strongly correlated to EPE (36). In addition, these findings are also of great clinical importance, as they demonstrate that women with EPE only show significant BBB disruption and are at highest risk for neurological symptoms, thereby confirming epidemiologic studies (4, 5). Although we did not examine the direct link between increased BBB permeability and neurological symptoms, it is well established that disruption of the BBB is a primary event in inducing neurological complications and the key event for seizure activity (10, 32). Thus, we show that specific circulating factors present in plasma from women with EPE only significantly increase BBB permeability and thereby make EPE women most at risk for life-threatening neurological symptoms.

Increased circulating levels of oxLDL in preeclampsia has been shown in several (15, 37–40), but not all (41), studies. In cardiovascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis, oxidative modification of LDL increases its atherogenicity and induces a wide variety of cellular responses, such as the induction and expression of adhesion molecules, proinflammatory cytokines, and reactive oxygen species, resulting in endothelial dysfunction (42). In preeclampsia, decidual vessels of the placenta show fibrinoid necrosis of the vascular wall and focal accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages, similar as in atherosclerosis, making oxLDL also a likely and important contributor in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia (43). Here, we found that oxLDL levels were increased in plasma from women with EPE but not in plasma from women with LPE, which was comparable to plasma from the NP group. This increase in EPE only compared to LPE and NP may be related to the finding that oxidative stress was found only in placentas from women with EPE (44), suggesting greater capacity for oxidative modification of LDL in EPE. In addition, we show that exogenous oxLDL to the levels as measured in plasma from women with EPE significantly increased BBB permeability in cerebral veins, comparable to women with EPE. Thus, increased oxLDL does not appear to be just a biomarker for neurological symptoms in EPE, but also the underlying cause of BBB disruption and a possible new target for understanding mechanisms of BBB disruption in several pathological states.

LOX-1 is an endothelial receptor for circulating oxLDL that has been studied extensively in pathological states, such as atherosclerosis, diabetes, coronary arterial heart disease, and hypertension (18, 33); however, data regarding LOX-1 activation in preeclampsia are scarce. LOX-1 was associated with preeclampsia for the first time in 2005 in a report that showed up-regulation of LOX-1 in preeclamptic hypoxic placentas (45). Recently, it was found that up-regulation of LOX-1 in HUVECs occurred in response to a 24-h exposure to plasma from women with preeclampsia and in a rat model of preeclampsia (20, 21). Here, we show for the first time involvement of LOX-1 in increasing BBB permeability after acute exposure of plasma from women with EPE for 3 h that contained high levels of circulating oxLDL. Because of the 3-h exposure time of the plasma, we did not determine possible up-regulation of LOX-1. As shown previously, up-regulation in HUVECs in response to plasma from women with preeclampsia did not occur until 24 h of exposure, while shorter exposure already caused increased production of ROS (21). These findings are in support of increased circulating ligands, such as circulating oxLDL activating LOX-1 to cause endothelial dysfunction. However, it remains to be determined in cerebral endothelial cells whether longer incubation would cause up-regulation of LOX-1 expression in response to plasma from women with EPE, as seen in HUVECs in response to plasma from women with preeclampsia (21). Notably, the LOX-1-mediated increase in BBB permeability with EPE plasma was confirmed in vivo in pregnant rats with pathologically high levels of LDL, which also showed symptoms such as increased blood pressure and growth-restricted fetuses. To our knowledge, few studies have investigated oxLDL/LOX-1 activation and vascular permeability. One study using mouse cultured cerebral endothelial cells showed that high concentrations of oxLDL were able to increase permeability (46). In the systemic vasculature, Nakano et al. (47) showed increased vascular permeability in mesenteric arteries from spontaneous hypertensive rats pretreated with oxLDL that was inhibited by a LOX-1 antibody. In this study, we propose a similar, but novel, mechanism that high levels of circulating oxLDL in EPE increase BBB permeability through LOX-1 activation.

LOX-1 activation has been shown to induce several intracellular signaling pathways, including increased expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules, triggering the CD40/CD40L pathway that activates the inflammatory cascade and increased production of reactive oxygen species, such as superoxide in endothelial cells (19). Increased levels of superoxide rapidly bind NO and form peroxynitrite, a toxic radical known to have deleterious effects on endothelial function (17, 25). Also, peroxynitrite generation has been reported in the maternal systemic vasculature in preeclampsia (48) and in HUVECs after exposure to plasma from women with preeclampsia (21). Here, we show that BBB permeability induced by either plasma from women with EPE or exogenous oxLDL to the levels of women with EPE was inhibited with the specific peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst FeTMPyP, demonstrating that peroxynitrite generation caused the increased BBB permeability. Our findings that oxLDL/LOX-1 activation induces peroxynitrite generation are supported by earlier reports that showed in different cell culture models that binding of oxLDL to LOX-1 decreased the intracellular concentration of NO by inducing the production of superoxide through NADPH oxidase (23) and increased peroxynitrite generation (49). Because NADPH oxidase expression and activity are greater in the cerebral vessels compared to systemic vasculature (50), the brain may be especially vulnerable for activation of NADPH oxidase and subsequent peroxynitrite generation. Notably, peroxynitrite also stimulates LOX-1 activation and a self-perpetuating mechanism develops that could cause extensive endothelial damage with deleterious effects for the maternal cerebral vasculature (17). Finally, these findings would explain the results from our previous study in which increased BBB permeability in response to plasma from severe preeclamptic women was prevented by VEGF receptor inhibition without increased circulating levels of VEGF compared to plasma from NP women (12). Phosphorylation of VEGF receptors results in a release of NO (51); thus, its inhibition would decrease the level of NO available for peroxynitrite generation, preventing BBB disruption (Fig. 5).

In summary, this is the first report to identify oxLDL as a circulating factor in EPE that significantly increases BBB permeability compared to LPE and thereby provides direct evidence for EPE and LPE having two different etiologies. In addition, we reveal a new mechanism for BBB disruption in EPE by oxLDL/LOX-1 activation and subsequent peroxynitrite generation. These novel findings will contribute to improving the identification and treatment of neurological complications in women diagnosed with EPE and possibly other neurological diseases where oxidative stress-induced BBB disruption is involved. Further studies are required to determine how BBB disruption induced by oxLDL leads to specific neurological symptoms, which could lead to treatment or prevention of these complications in preeclampsia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Karen Oppenheimer (Obstetrics/Gynecology Molecular Core Facility, University of Vermont) for performing the RT-PCR and Dr. Siu-Lung Chan (Department of Neurology, University of Vermont) for supervising the ELISA.

Also, the authors gratefully acknowledge the support of U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant RO1-NS045940, Neural Environment Cluster supplement RO1-NS045940-06S1, and American Recovery and Reinvestment Act supplement RO1-NS045940-05S1. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the support of U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants PO1-HL095488 and HL-071944 and the Totman Medical Research Trust. Lastly, the authors acknowledge the support of the Program Project Grant (PPG) core of the University of Pittsburgh, including PPG grant P01HD30367, and Magee-Womens Hospital CRC grant MO1-RR000056/1 UL1-RR024153-01.

Footnotes

- BBB

- blood-brain barrier

- EPE

- early-onset preeclampsia

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- LDL

- low-density lipoprotein

- LOX-1

- lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1

- Lp

- hydraulic conductivity

- LP-CTL

- late-pregnancy control

- LPE

- late-onset preeclampsia

- LP-HC

- late-pregnancy high-cholesterol

- MCA

- middle cerebral artery

- NO

- nitric oxide

- NonP

- nonpregnant

- NP

- normal pregnancy

- oxLDL

- oxidized low-density lipoprotein

REFERENCES

- 1. Duley L. (2009) The global impact of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Sem. Perinatol. 33, 130–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zeeman G. G. (2009) Neurologic complications of pre-eclampsia. Sem. Perinatol. 33, 166–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Okanloma K. A., Moodley J. (2000) Neurological complications associated with the pre-eclampsia/eclampsia syndrome. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 71, 223–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ogge G., Chaiworapongsa T., Romero R., Hussein Y., Kusanovic J. P., Yeo L., Kim C. J., Hassan S. S. (2011) Placental lesions associated with maternal underperfusion are more frequent in early-onset than in late-onset preeclampsia. J. Perinat. Med. 39, 641–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Douglas K. A., Redman C. W. (1994) Eclampsia in the United Kingdom. Brit. Med. J. 309, 1395–1400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. von Dadelszen P., Magee L. A., Roberts J. M. (2003) Subclassification of preeclampsia. Hypertens. Pregnancy 22, 143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Loureiro R., Leite C. C., Kahhale S., Freire S., Sousa B., Cardoso E. F., Alves E. A., Borba P., Cerri G. G., Zugaib M. (2003) Diffusion imaging may predict reversible brain lesions in eclampsia and severe preeclampsia: initial experience. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 189, 1350–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cipolla M. J. (2007) Cerebrovascular function in pregnancy and eclampsia. Hypertension 50, 14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Engelter S. T., Provenzale J. M., Petrella J. R. (2000) Assessment of vasogenic edema in eclampsia using diffusion imaging. Neuroradiology 42, 818–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Friedman A., Kaufer D., Heinemann U. (2009) Blood-brain barrier breakdown-inducing astrocytic transformation: novel targets for the prevention of epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 85, 142–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Foyouzi N., Norwitz E. R., Tsen L. C., Buhimschi C. S., Buhimschi I. A. (2006) Placental growth factor in the cerebrospinal fluid of women with preeclampsia. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 92, 32–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Amburgey O. A., Chapman A. C., May V., Bernstein I. M., Cipolla M. J. (2010) Plasma from preeclamptic women increases blood-brain barrier permeability: role of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. Hypertension 56, 1003–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hubel C. A., Lyall F., Weissfeld L., Gandley R. E., Roberts J. M. (1998) Small low-density lipoproteins and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 are increased in association with hyperlipidemia in preeclampsia. Metabolism 47, 1281–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Belo L., Santos-Silva A., Caslake M., Pereira-Leite L., Quintanilha A., Rebelo I. (2005) Oxidized-LDL levels in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies: contribution of LDL particle size. Atherosclerosis 183, 185–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Qiu C., Phung T. T., Vadachkoria S., Muy-Rivera M., Sanchez S. E., Williams M. A. (2006) Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxidized LDL) and the risk of preeclampsia. Physiol. Res. 55, 491–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Redman C. W., Sargent I. L. (2005) Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science 308, 1592–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buhimschi I. A., Saade G. R., Chwalisz K., Garfield R. E. (1998) The nitric oxide pathway in pre-eclampsia: pathophysiological implications. Hum. Reprod. Update 4, 25–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ogura S., Kakino A., Sato Y., Fujita Y., Iwamoto S., Otsui K., Yoshimoto R., Sawamura T. (2009) Lox-1: the multifunctional receptor underlying cardiovascular dysfunction. Circulation 73, 1993–1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mitra S., Goyal T., Mehta J. L. (2011) Oxidized LDL, LOX-1 and atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 25, 419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morton J. S., Abdalvand A., Jiang Y., Sawamura T., Uwiera R. R., Davidge S. T. (2012) Lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein 1 receptor in a reduced uteroplacental perfusion pressure rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension 59, 1014–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sankaralingam S., Xu Y., Sawamura T., Davidge S. T. (2009) Increased lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 expression in the maternal vasculature of women with preeclampsia: role for peroxynitrite. Hypertension 53, 270–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sanchez S. E., Williams M. A., Muy-Rivera M., Qiu C., Vadachkoria S., Bazul V. (2005) A case-control study of oxidized low density lipoproteins and preeclampsia risk. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 21, 193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cominacini L., Rigoni A., Pasini A. F., Garbin U., Davoli A., Campagnola M., Pastorino A. M., Lo Cascio V., Sawamura T. (2001) The binding of oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) to ox-LDL receptor-1 reduces the intracellular concentration of nitric oxide in endothelial cells through an increased production of superoxide. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 13750–13755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen X. P., Xun K. L., Wu Q., Zhang T. T., Shi J. S., Du G. H. (2007) Oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor-1 mediates oxidized low density lipoprotein-induced apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: role of reactive oxygen species. Vasc. Pharmacol. 47, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beckman J. S., Koppenol W. H. (1996) Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 271, C1424–C1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roberts T. J., Chapman A. C., Cipolla M. J. (2009) PPAR-gamma agonist rosiglitazone reverses increased cerebral venous hydraulic conductivity during hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H1347–H1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schreurs M. P., Houston E. M., May V., Cipolla M. J. (2012) The adaptation of the blood-brain barrier to vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor during pregnancy. FASEB J. 26, 355–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mayhan W. G. (1995) Role of nitric oxide in disruption of the blood-brain barrier during acute hypertension. Brain Res. 686, 99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xie Z., Wei M., Morgan T. E., Fabrizio P., Han D., Finch C. E., Longo V. D. (2002) Peroxynitrite mediates neurotoxicity of amyloid beta-peptide1-42- and lipopolysaccharide-activated microglia. J. Neurosci. 22, 3484–3492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Palomares S. M., Gardner-Morse I., Sweet J. G., Cipolla M. J. (2012) Peroxynitrite decomposition with FeTMPyP improves plasma-induced vascular dysfunction and infarction during mild but not severe hyperglycemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 32, 1035–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schreurs M. P., Cipolla M. J. (2012) Pregnancy enhances the effects of of hypercholesterolemia in posterior cerebral arteries. [E-pub ahead of print] Reprod. Sci.. doi: 10.1177/1933719112459228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marchi N., Teng Q., Ghosh C., Fan Q., Nguyen M. T., Desai N. K., Bawa H., Rasmussen P., Masaryk T. K., Janigro D. (2010) Blood-brain barrier damage, but not parenchymal white blood cells, is a hallmark of seizure activity. Brain Res. 1353, 176–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen M., Masaki T., Sawamura T. (2002) LOX-1, the receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein identified from endothelial cells: implications in endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Pharmacol. Ther. 95, 89–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Enquobahrie D. A., Williams M. A., Butler C. L., Frederick I. O., Miller R. S., Luthy D. A. (2004) Maternal plasma lipid concentrations in early pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia. Am. J. Hypertens. 17, 574–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abbott N. J., Ronnback L., Hansson E. (2006) Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 41–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Neal C. R., Hunter A. J., Harper S. J., Soothill P. W., Bates D. O. (2004) Plasma from women with severe pre-eclampsia increases microvascular permeability in an animal model in vivo. Clin. Sci. 107, 399–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim Y. J., Park H., Lee H. Y., Ahn Y. M., Ha E. H., Suh S. H., Pang M. G. (2007) Paraoxonase gene polymorphism, serum lipid, and oxidized low-density lipoprotein in preeclampsia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 133, 47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Uzun H., Benian A., Madazli R., Topcuoglu M. A., Aydin S., Albayrak M. (2005) Circulating oxidized low-density lipoprotein and paraoxonase activity in preeclampsia. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 60, 195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Branch D. W., Mitchell M. D., Miller E., Palinski W., Witztum J. L. (1994) Pre-eclampsia and serum antibodies to oxidised low-density lipoprotein. Lancet 343, 645–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reyes L. M., Garcia R. G., Ruiz S. L., Broadhurst D., Aroca G., Davidge S. T., Lopez-Jaramillo P. (2012) Angiogenic imbalance and plasma lipid alterations in women with preeclampsia from a developing country. Growth Factors 30, 158–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pecks U., Caspers R., Schiessl B., Bauerschlag D., Piroth D., Maass N., Rath W. (2012) The evaluation of the oxidative state of low-density lipoproteins in intrauterine growth restriction and preeclampsia. Hypertens. Pregnancy 31, 156–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ross R. (1993) The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature 362, 801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Staff A. C., Dechend R., Pijnenborg R. (2010) Learning from the placenta: acute atherosis and vascular remodeling in preeclampsia-novel aspects for atherosclerosis and future cardiovascular health. Hypertension 56, 1026–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wikstrom A.K., Nash P., Eriksson U. J., Olovsson M. H. (2009) Evidence of increased oxidative stress and a change in the plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 to PAI-2 ratio in early-onset but not late-onset preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 201, 597.e1—597.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee H., Park H., Kim Y. J., Kim H. J., Ahn Y. M., Park B., Park J. H., Lee B. E. (2005) Expression of lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1) in human preeclamptic placenta: possible implications in the process of trophoblast apoptosis. Placenta 26, 226–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lin Y. L., Chang H. C., Chen T. L., Chang J. H., Chiu W. T., Lin J. W., Chen R. M. (2010) Resveratrol protects against oxidized LDL-induced breakage of the blood-brain barrier by lessening disruption of tight junctions and apoptotic insults to mouse cerebrovascular endothelial cells. J. Nutr. 140, 2187–2192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nakano A., Inoue N., Sato Y., Nishimichi N., Takikawa K., Fujita Y., Kakino A., Otsui K., Yamaguchi S., Matsuda H., Sawamura T. (2010) LOX-1 mediates vascular lipid retention under hypertensive state. J. Hypertens. 28, 1273–1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Roggensack A. M., Zhang Y., Davidge S. T. (1999) Evidence for peroxynitrite formation in the vasculature of women with preeclampsia. Hypertension 33, 83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Heeba G., Hassan M. K., Khalifa M., Malinski T. (2007) Adverse balance of nitric oxide/peroxynitrite in the dysfunctional endothelium can be reversed by statins. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 50, 391–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Miller A. A., Drummond G. R., De Silva T. M., Mast A. E., Hickey H., Williams J. P., Broughton B. R., Sobey C. G. (2009) NADPH oxidase activity is higher in cerebral versus systemic arteries of four animal species: role of Nox2. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 296, H220–H225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kroll J., Waltenberger J. (1999) A novel function of VEGF receptor-2 (KDR): rapid release of nitric oxide in response to VEGF-A stimulation in endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 265, 636–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]