Abstract

We investigated species diversity and distribution patterns of the marine red alga Portieria in the Philippine archipelago. Species boundaries were tested based on mitochondrial, plastid and nuclear encoded loci, using a general mixed Yule-coalescent (GMYC) model-based approach and a Bayesian multilocus species delimitation method. The outcome of the GMYC analysis of the mitochondrial encoded cox2-3 dataset was highly congruent with the multilocus analysis. In stark contrast with the current morphology-based assumption that the genus includes a single, widely distributed species in the Indo-West Pacific (Portieria hornemannii), DNA-based species delimitation resulted in the recognition of 21 species within the Philippines. Species distributions were found to be highly structured with most species restricted to island groups within the archipelago. These extremely narrow species ranges and high levels of intra-archipelagic endemism contrast with the wide-held belief that marine organisms generally have large geographical ranges and that endemism is at most restricted to the archipelagic level. Our results indicate that speciation in the marine environment may occur at spatial scales smaller than 100 km, comparable with some terrestrial systems. Our finding of fine-scale endemism has important consequences for marine conservation and management.

Keywords: biodiversity, Coral Triangle, cryptic species, Indo-West Pacific, marine biogeography, species delimitation

1. Introduction

A traditional view holds that many marine species have large geographical ranges because of their high dispersal potential by pelagic larval stages or propagules, and a lack of apparent dispersal barriers in the sea [1,2]. The reef-rich and diverse Indo-West Pacific (IWP) biogeographic region harbours species with particularly wide ranges and little archipelagic endemism [3]. Most species are characterized by subbasinal distributions, being widespread in either the Indian or Pacific Ocean, but a substantial fraction spans both oceans [4].

However, the view that most marine species have broad ranges is being challenged. Molecular evidence indicates that some marine species comprise several cryptic species (i.e. distinct species that are erroneously classified under a single species due to the lack of clear morphological differences) [2,5,6]. While in some studies cryptic species themselves were found to be wide-ranging [7,8], there is accumulating evidence for the prevalence of geographically restricted cryptic species in allegedly widely distributed marine organisms [9–15]. Studies focusing on marine invertebrates and fish have shown that proportions of range-restricted species are highest in remote peripheral archipelagos [16,17], but archipelagic endemism has also been demonstrated in the central IWP [4,9,18].

The spatial scale at which neutral diversification occurs is a function of dispersal distance and frequency [4,19]. High dispersal or gene-flow will generally prevent diversification and result in large geographical ranges, while ineffective dispersal will result in the absence of species in a given locality. At intermediate levels of dispersal, populations may diverge to form new species. Consequently, many studies focus on the link between intrinsic dispersal capacity (e.g. pelagic larval duration, behaviour and ecology), geographical range and diversification [20–22]. The observation that the Society Islands and Tuamotu harbour their own endemic gastropod species led Meyer et al. [9] to conclude that speciation in the marine environment may act at much more local scales than previously anticipated. Despite indications for archipelagic endemism there are no reports of intra-archipelagic endemism of shallow-water marine organisms, suggesting that dispersal within archipelagos is too high to allow diversification. This contrasts markedly with terrestrial organisms, for which intra-archipelagic endemism is common [23–25].

Compared with marine invertebrates and fish, marine macroalgae are considered poor dispersers [26–30]. The spores or zygotes of most marine macroalgae are typically short-lived and often negatively buoyant [31]. A few species have high dispersal potential by detached and floating reproductive thallus fragments that act as propagules. In the absence of such propagules, the limited dispersal capacity of most macroalgae may reflect strongly on diversity patterns and the spatial scale at which speciation takes place. Several morphologically well-circumscribed and easily recognizable macroalgal species are known to have restricted distributions [31,32]. Moreover, wide distribution ranges of many algae are an artefact of pervasive cryptic diversity [10,33–37].

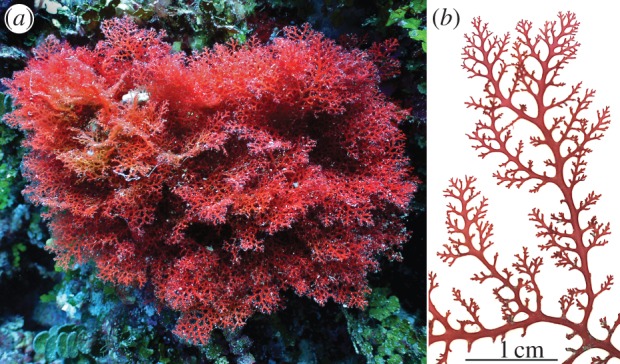

We aim to assess species distribution patterns of marine plants in the Philippine archipelago, focusing on the red macroalgal genus Portieria. The genus is a member of the red algal family Rhizophyllidaceae, which, next to Portieria, includes the (sub)tropical and species-poor genera Contarinia, Nesophila and Ochtodes [38]. Portieria typically forms bushy plants, up to 15 cm high, composed of flattened fronds with a typical branching pattern (figure 1), which makes the genus easily recognizable in the field. Like most red seaweeds, Portieria is characterized by a complex, triphasic life cycle, which includes two free-living stages of different ploidy levels—a diploid (tetrasporophyte) stage and a haploid (gametophyte) stage—as well as a diploid carposporophyte stage, which develops on the female gametophyte [38]. The genus is broadly distributed in the Indo-West Pacific and is common on coral reefs in the Philippines where it occurs from the shallow subtidal to 40 m depth. Owing to its secondary metabolic compounds, Portieria persists even in areas with extensive grazing by herbivorous fish [39].

Figure 1.

Portieria hornemannii. (a) Plant growing in the shallow subtidal (image courtesy of David Burdick). (b) detail of branches.

There is considerable uncertainty as to the number of species in the genus. Seven species names are currently accepted in AlgaeBase [40]. Wiseman [41], who conducted the only comprehensive morphological study of Portieria, recognized only one species, P. hornemannii. Other authors have expressed doubts on this highly restricted view and have recognized a varying number of species [42,43]. Here we use multilocus DNA sequence data to test species boundaries and assess patterns of diversity and distribution.

We focus on the Philippine archipelago as a suitable study region. The archipelago is situated in the northern corner of the Coral Triangle, a region that is known as a global centre of marine biodiversity [44]. The Philippines has a complex geometry, with multiple islands, passages and basins that are interconnected by ocean currents and human activities [45,46]. This high connectivity between islands and basins would suggest the potential for high dispersal and homogeneous species distribution patterns of marine species within the Philippines, which contrasts with the exceptional regional endemism observed for terrestrial habitats [47,48].

2. Material and methods

(a). Sampling

A total of 265 Portieria specimens were collected by snorkelling or SCUBA diving from 25 sites (approx. 100 m long stretches of coastline) throughout the Philippines (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S3). Specimens are vouchered in the Ghent University Herbarium (GENT) or the Institute of Environmental and Marine Sciences at Silliman University. A list of specimens with collection data and GenBank accession numbers is provided in the electronic supplementary material, table S1.

(b). DNA sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from ethanol-preserved specimens using a modified CTAB method [35]. We amplified three unlinked loci: the mitochondrial encoded cox2 gene (partial) and cox2-3 spacer (approx. 320 bp, further referred to as ‘cox2-3’), the chloroplast encoded rbcL gene (partial) and rbcL-rbcS-spacer (approx. 540 bp, further referred to as ‘rbcL’) and nuclear elongation factor 2 (EF2) gene (approx. 610 bp; see the electronic supplementary material, table S3). PCR conditions and primer sequences are detailed in the electronic supplementary material, table S2. PCR products were purified using ExoSAP-IT (USB) and sequenced using BigDye v. 3.1 (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 3100 automated DNA sequencer. Sequences were submitted to EMBL/GenBank under accession numbers HF546576–HF546974. DNA sequences were aligned using ClustalW [49]. Sequence matrix information is given in the electronic supplementary material, table S3.

(c). DNA-based species delimitation and phylogeny

Species boundaries were tested using analyses of single- and multilocus genetic data. The single-locus DNA trees were based on separate analyses of 67 cox2-3, rbcL and EF2 sequence alignments and were analysed using a GMYC model approach [50,51]. This likelihood-based method aims to detect species boundaries by optimizing the transition from interspecific branching (Yule model) to intraspecific branching (neutral coalescent model) on an ultrametric tree. Ultrametric trees were obtained by Bayesian analyses in Beast v. 1.6.1 [52], under a GTR + I + G model with divergence times estimated under an uncorrelated lognormal relaxed molecular clock model [53] and the constant population size coalescent as the tree prior. Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analyses were run for 50 million generations, sampling every 10 000 generations. The output was diagnosed for convergence using Tracer v. 1.5 [54], and summary statistics and trees were generated using the last 40 million generations with TreeAnnotator v. 1.5.3. GMYC analyses were performed on the consensus trees under the single-threshold model, using the SPLITS package [51] in R [55].

Recent studies have raised concerns about the accuracy of defining species boundaries based on single-locus data because of problems related to incomplete lineage sorting, resulting in gene tree–species tree incongruence [56–59]. Therefore, we tested species boundaries using multilocus data, including the cox2-3, rbcL and EF2 datasets, which contained the same 67 specimens initially used for the GMYC analyses. Individual gene trees were constructed using Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML). Bayesian trees were estimated using MrBayes v. 3.1.2 under a GTR + I + G model [60]. Two parallel runs, each consisting of four incrementally heated chains, were run for five million generations, sampling every 1000th generation. Convergence of log-likelihoods and parameter values was assessed in Tracer v. 1.4 [54]. A burn-in sample of 1000 trees was removed before constructing the majority rule consensus tree. ML trees and associated rapid bootstrap support were obtained using the GTR + CAT model in the program RAxML v. 7.2.8 [61].

Individual gene trees were visually inspected to identify reciprocal monophyletic groups that were concordantly supported by the three loci as evidence for species boundaries in a genealogical concordance approach [62]. Genealogical concordance of unlinked loci is expected to be present among well-diverged lineages. However, the criteria of reciprocal monophyly and strict congruence will probably fail to detect boundaries between recently diverging species [63]. Therefore, we used a recently developed Bayesian method, BP&P, which aims to detect signals of species divergence in multiple gene trees, even in the absence of monophyly, based on models combining species phylogeny and the ancestral coalescent process, and assuming no admixture following the speciation event [64]. The method calculates posterior probabilities of potential species delimitations given a user-supplied species tree and multilocus sequence data. A species tree was estimated using *BEAST [65], a Bayesian method that coestimates multiple gene trees embedded in a shared species tree using multispecies coalescent estimates. For the species tree estimation, specimens were a priori assigned to species based on the results of the cox2-3 GMYC results. *BEAST analysis was performed with unlinked models for the three loci: GTR + I + G substitution model, uncorrelated lognormal relaxed molecular clock model and Yule species tree model. Two independent MCMC analyses were run for 20 million generations. Convergence of the runs was assessed by visual examination of parameter traces and marginal densities using Tracer, and the posterior distribution of trees was summarized from the MCMC output excluding the first 10 per cent as burn-in. BP&P v. 2.0 was run using ‘algorithm 0’, fine-tuning parameter ɛ = 5, and with each species delimitation model assigned equal prior probability. Because the prior distributions on the ancestral population size (Θ) and root age (τ0) can affect the posterior probabilities for models, with large values for Θ and small values for τ0 favouring conservative models containing fewer species [64], we ran the analyses with three different combinations of prior, as proposed by Leaché & Fujita [66]. Two independent reversible jump MCMC analyses were run for 100 000 generations. In order to verify whether the GMYC analysis of the cox2-3 dataset might underestimate species diversity, we reran the BP&P analyses with the GMYC clusters of clade V1 and clade B subdivided into multiple entities.

Divergence times were estimated based on the cox2-3 calibration reported by Zuccarello & West [67], being 0.25–0.3 per cent sequence divergence per Myr. Although this calibration has been tested in other red algal groups [68], the estimated divergence times have to be interpreted with care because of possible rate variations across red algal lineages and uncertainties regarding the calibration point used (Panama Isthmus). Several recent studies have found that divergence times between trans-isthmian species pairs are often much older than 3 Ma, indicating that in these cases the final closure of the Panama Isthmus may not have been the initial cause of divergence between populations [10,69,70].

(d). Species ranges and total species richness

Geographical ranges of species were estimated using locality data of 265 specimens, identified based on cox2-3 sequence data. Cox2-3 was the marker of choice because it was more variable and showed faster coalescence within species lineages compared with the other two loci, and thus more accurately reflected species boundaries in Portieria (see the electronic supplementary material, table S3). Species richness based on our sampling was estimated using the incidence-based first-order jackknife estimator implemented in EstimateS v. 8.2 [71]. The values derive from an extrapolation of diversity based on the frequency of observing species restricted to a single locality. We provide a rough estimate of the total Portieria diversity in the Philippines by extrapolating the richness estimates beyond the current sample size. Therefore, various asymptotic functions (power, exponential, Monod, negative exponential, asymptotic regression, rational and Lecointre function) were fitted through the data using nonlinear least-squares estimates. Model selection was based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) [72,73]. Nonlinear regressions and model comparison were carried out in R.

3. Results

(a). Species delimitation and phylogeny

In the single-locus method for species delimitation, branch lengths in the ultrametric gene trees were analysed to test species boundaries (figure 2). For the cox2-3 tree, the likelihood of the GMYC model was significantly higher (p < 0.001) than that of the null model of uniform coalescent branching rates (see the electronic supplementary material, table S3). In the rbcL and EF2 trees, the difference between these two models was marginally significant (0.01 < p < 0.05). The results indicate the presence of multiple species in our sample. For the cox2-3 data, the model estimates 21 species clusters, with a narrow confidence interval ranging from 20 to 25. Fitting the model on the rbcL and EF2 trees resulted in slightly fewer species clusters (20 and 18, respectively), with wider confidence intervals (see the electronic supplementary material, table S3).

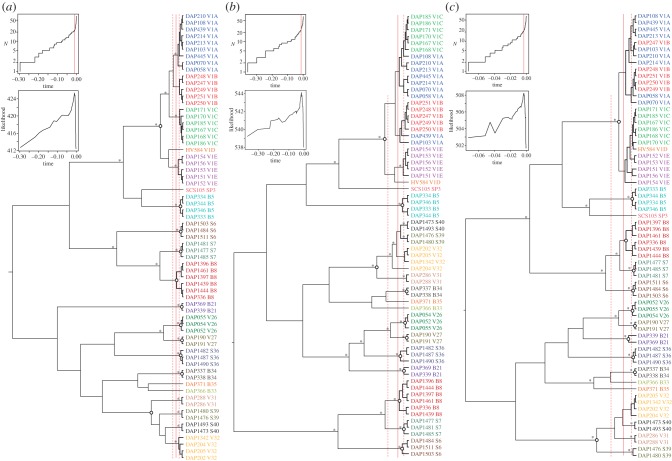

Figure 2.

GMYC-based species delimitation based on the (a) cox2-3, (c) rbcL and (b) EF2 gene trees. Ultrametric trees were obtained by Bayesian relaxed molecular clock analyses. Open circles indicate reciprocal monophyletic terminal clades that were concordantly recovered in the three gene trees. Branches supported by posterior probabilities greater than 0.95 and ML bootstrap support greater than 80 are indicated with an asterisk. Lineages-through-time (left) and single-threshold GMYC likelihood profile plots (right) are shown for the three gene trees. The solid red lines indicate the maximum-likelihood transition point of the switch in branching rates from interspecific to intraspecific events, as estimated by the GMYC model; the confidence intervals are indicated by the dashed red lines. Results of the GMYC analyses are summarized in electronic supplementary material, table S3.

Genealogical concordance was assessed between the cox2-3, rbcL and EF2 trees. Eleven reciprocally monophyletic clades were concordantly recovered in the three gene genealogies (open circles in figure 2), in addition to three singletons (B33, B35 and SP3). Incongruence was restricted to the V1 and V32 clades. The five V1 species clusters in the cox2-3 tree (V1A-E) were either para- or polyphyletic in the EF2 and rbcL trees. The V32 clade in the cox2-3 and EF2 gene trees was paraphyletic in the rbcL tree.

The multilocus Bayesian species delimitation results are indicated in the species phylogeny (guide tree) in figure 3a. When assuming that the 21 GMYC clusters correspond to species, the Bayesian species delimitation supported the guide tree with high speciation probabilities (1 or 0.99) on all nodes. The results were stable over a broad range of prior settings relating to effective population size and root ages. The Bayesian species delimitation did not support guide trees where the number of species had been increased (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S1), indicating that the species diversity was not underestimated by the GMYC analysis of the cox2-3 dataset.

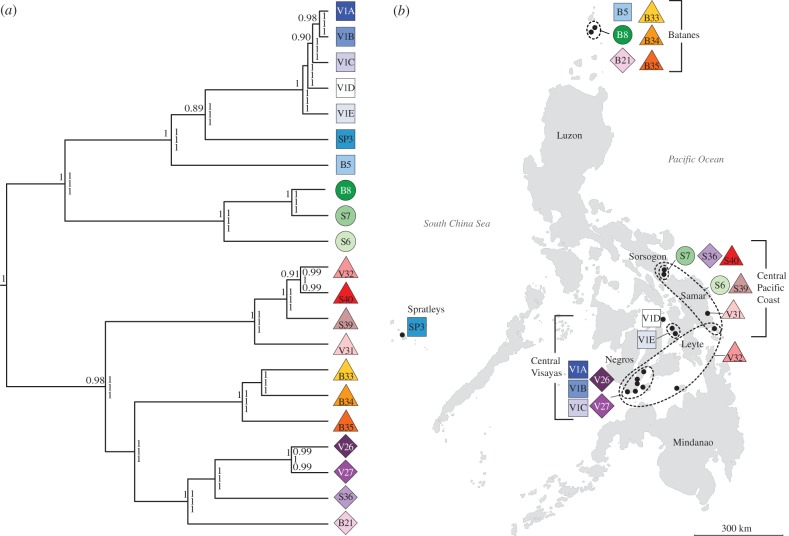

Figure 3.

(a) Bayesian species tree inferred using *BEAST with numbers above branches representing posterior probability values (only values greater than 0.85 are shown). The speciation probabilities, analysed using BP&P, are provided for each node under three combinations of priors: top, assuming large population sizes Θ ∼ G(1, 10) and deep divergences τ0 ∼ G(1,10); middle, assuming small population sizes Θ ∼ G(2,2000) and shallow divergences τ0 ∼ G(2,2000); bottom, assuming large populations sizes Θ ∼ G(1,10) and relatively shallow divergences τ0 ∼ G(2,2000). (b) Geographical distributions of Portieria species within the Philippines. Most species exhibit intra-archipelagic endemism; only three species are more widely distributed within the archipelago (S6, S39 and V32). Detailed species distributions are provided in the electronic supplementary material, figure S3.

Divergence time estimates (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S2) suggest that Portieria may have originated as early as the Late Eocene (around 35 Ma), and mainly diversified in the Oligo-Miocene, with possibly recent speciation events in the Plio-Pleistocene in clade V1.

(b). Species distribution patterns

Of the 21 identified Portieria species in the Philippines, not a single one was found throughout the study area (see the electronic supplementary material, table S4 and figure S3; figure 3b). Twelve species were confined to one or two sites, while only four species were found at more than three sites (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S3). With three exceptions (V32, S6 and S39), specimens of a species were always found within 80 km from each other. The diversity found in Batanes was very distinct from the other sites, with none of the species occurring outside the area. The central Visayas shared a single species (V32) with Samar (approx. 350 km). Only two species (S6 and S39) are shared between Sorsogon and Samar (approx. 250 km).

In several sites and on most islands, different Portieria species occurred in sympatry. In many cases, these species were phylogenetically distantly related; for example, four species from four different clades co-occurred in Chavayan (Batanes; see figure 3b and electronic supplementary material, figure S3). Sister or closely related species were also found in sympatry. A striking example is the central Visayas, which harboured the closely related species V1A, V1B and V1C, along with the more distantly related species V32, V26 and V27.

Given the narrow geographical range of most species, it is highly unlikely that our sampling strategy resulted in a complete coverage of Portieria diversity. Extrapolating richness beyond the current sampling effort (i.e. 25 localities) to its asymptote resulted to an estimate of 45 (±5) species (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S4).

4. Discussion

Molecular reassessment of the diversity of the red algal genus Portieria in the Philippines demonstrates that previous morphology-based species circumscriptions dramatically underestimated the diversity in the region. In contrast to the assumed presence of one to three species in the Philippines [74], this study showed the existence of at least 21 cryptic Portieria species. Below we discuss the implication of our results with respect to diversity estimates, intra-archipelagic endemism and speciation in the marine environment, and the consequences of small species ranges in relation to marine conservation.

(a). High levels of cryptic species diversity

Unveiling cryptic diversity in marine macroalgae is not uncommon [10,14,33–36], but the degree to which we do so here is unprecedented. The GMYC model approach based on the mitochondrial encoded cox2-3 spacer region resulted in 21 clusters of specimens which were reciprocally monophyletic and sufficiently distinct from other such lineages to regard them as separately evolving lineages (‘species’) [51]. Comparing GMYC results of the cox2-3 data with the chloroplast encoded rbcL and nuclear encoded EF2 gene trees, we observed a large degree of congruence, lending additional support to regard them as species [62]. Comparison of the mitochondrial, plastid and nuclear gene trees indicated that coalescence is faster for organellar DNA than for the nuclear encoded locus, an observation that is congruent with population genetic theory, which predicts that the effective population size of nuclear DNA is four times as high for diploid organisms compared with organellar DNA, which is haploid and uniparentally inherited [63].

The congruence that we observe between the single-locus (separate analyses of cox2-3, rbcL and EF2 data) and multilocus species delimitation analyses is an important finding. It gives credit to popular barcoding initiatives that mostly rely on some sort of genetic exclusivity criterion (e.g. reciprocal monophyly and genetic distance) and single-locus datasets (usually a mitochondrial marker). It is generally safe to ignore problems relating to incomplete lineage sorting and ancestral polymorphism in lineages that diverged long enough from one another. Given enough time, these species will be recognized using the criterion of reciprocal monophyly at each of the sampled loci [56,63,75]. Recently diverged taxa, however, are more likely to go unnoticed using exclusivity criteria (i.e. they have a higher false-negative rate). In such cases, it is important to select markers that show fast coalescence. In our datasets, the mitochondrial locus appeared to have a somewhat higher coalescent rate when compared with the chloroplast locus, but these results may be stochastic as there are no apparent differences in heritability of both organelle genomes.

(b). Intra-archipelagic endemism and fine spatial scale of speciation

Species distributions were found to be highly structured within the Philippine archipelago. For example, none of the Portieria species were shared between the northern and central collecting sites, and there was limited species overlap between the central Visayan and the Central Pacific Coast sites (figure 3b). The distribution of species V32 presents the largest geographical range of an individual Portieria species in the region, which stretches slightly over 300 km. At smaller spatial scales, similarity in species composition was higher.

Our study adds to the growing body of evidence that the geographical ranges of many marine species are more restricted then previously assumed. For example, the gastropod Astralium rhodostomum, with a perceived wide geographical range across the IWP, was found to consist of at least 30 cryptic species, all but one confined to a single archipelago [9]. Similar observations in molluscs, crustaceans and fishes indicate that archipelagic endemism is common in diverse groups of marine organisms [4,18,76,77].

The distribution pattern of Portieria in the Philippines demonstrates that species-level diversity may be geographically structured at even smaller scales (less than 100 km) within a single archipelago. The range sizes found in this study are unseen for marine benthic species, and are reminiscent of distribution patterns in terrestrial organisms where examples of intra-archipelagic endemism abound [24,25]. These results are even more interesting in view of a high physical connectivity between islands and basins [45,46], which would intuitively facilitate dispersal of marine organisms, resulting in much larger species distributions.

Our observation of fine-scale biogeographic structure suggests that dispersal limitation and speciation of marine macroalgae in archipelagos may act at much smaller geographical scales than is commonly assumed. Although several studies on marine invertebrates and fish have indicated population genetic structure among and within basins of the Philippine archipelago [78–80] and the Indo-Malayan region in general [81,82], the geographical scale at which these populations diverge is considerably larger compared with Portieria. Identical physical oceanographic processes probably yield markedly different results in organisms with different dispersal and/or life cycle strategies. As in many other seaweeds, the apparent absence of propagules in Portieria probably limits dispersal capacity, and this may reflect the spatial scale at which speciation takes place.

The high species diversity of Portieria in the Philippines is in line with the high biodiversity of other marine groups in the Coral Triangle [44]. Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the high biodiversity in the region, including elevated local speciation rates (centre of origin hypothesis) and accumulation of species formed elsewhere (centre of accumulation hypothesis) [83,84]. Speciation at small spatial scales of the V1 clade may be attributed to the complex geography of the region and possibly took place during Pleistocene periods of glacially lowered sea level when seas (e.g. the South China, Sulu, Philippine, Celebes, Molucca and Banda seas) became landlocked, resulting in prolonged geographical isolation [2,44,83,85]. Accumulation of species may have resulted from integration of distinct biotas by tectonic movement over the past 50 million years, and more recent dispersal events [44,86–88]. The antiquity of the main Portieria clades (Oligo-Miocene) and the presence of more recent diversifications within these clades (Plio-Pleistocene) suggest that the evolution of Portieria in the Philippines may be the product of multiple processes, including accumulation and/or diversification over time frames of tens of millions of years, and more recent speciation events. Evidently, these hypotheses will need to be tested by additional taxon sampling and phylogenetic analysis of Portieria across its geographical range in the Indo-West Pacific.

(c). Marine conservation

Our findings have important consequences for marine conservation management in threatened reef ecosystems, such as those in the Philippine archipelago [89]. A traditional view held that marine species are more resilient to extinction because of their large geographical ranges, and therefore conserving a limited number of marine biodiversity hotspots would save most species from extinction [1,90]. The finding of fine-scale endemism implies that conservation efforts in archipelagos will need to focus on all islands rather than on a few presumed biodiversity hotspots [9].

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Bucol, A. Candido, J. Lucañas, R. Ladiao, D. G. Payo and W. Villaver for field sampling assistance, David Burdick for kindly providing an underwater photograph of Portieria, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. This research was funded by the Flemish Interuniversity Council (PhD grant to D.A.P.), the Belgian Focal Point to the Global Taxonomy Initiative, the Research Foundation, Flanders (post-doctoral grant to F.L.) and the Australian Research Council (FT110100585).

References

- 1.Roberts CM, et al. 2002. Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science 295, 1280–1284 10.1126/science.1067728 (doi:10.1126/science.1067728) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palumbi SR. 1994. Genetic divergence, reproductive isolation and marine speciation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 25, 547–572 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.25.1.547 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.25.1.547) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randall JE. 1998. Zoogeography of shore fishes of the Indo-Pacific region. Zool. Stud. 37, 227–268 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulay G, Meyer C. 2002. Diversification in the tropical pacific: Comparisons between marine and terrestrial systems and the importance of founder speciation. Integr. Comp. Biol. 42, 922–934 10.1093/icb/42.5.922 (doi:10.1093/icb/42.5.922) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowlton N. 1993. Sibling species in the sea. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 24, 189–216 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.24.1.189 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.24.1.189) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bickford D, Lohman DJ, Sodhi NS, Ng PKL, Meier R, Winker K, Ingram KK, Das I. 2007. Cryptic species as a window on diversity and conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 148–155 10.1016/j.tree.2006.11.004 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.11.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colborn J, Crabtree RE, Shaklee JB, Pfeiler E, Bowen BW. 2001. The evolutionary enigma of bonefishes (Albula spp.): cryptic species and ancient separations in a globally distributed shorefish. Evolution 55, 807–820 10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[0807:teeoba]2.0.co;2 (doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[0807:teeoba]2.0.co;2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lessios HA, Kessing BD, Pearse JS. 2001. Population structure and speciation in tropical seas: global phylogeography of the sea urchin Diadema. Evolution 55, 955–975 10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[0955:psasit]2.0.co;2 (doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[0955:psasit]2.0.co;2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer CP, Geller JB, Paulay G. 2005. Fine scale endemism on coral reefs: archipelagic differentiation in turbinid gastropods. Evolution 59, 113–125 10.1554/04-194 (doi:10.1554/04-194) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tronholm A, Leliaert F, Sanson M, Afonso-Carrillo J, Tyberghein L, Verbruggen H, De Clerck O. 2012. Contrasting geographical distributions as a result of thermal tolerance and long-distance dispersal in two allegedly widespread tropical brown algae. PLoS ONE 7, e30813. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030813 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030813) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kooistra W, Sarno D, Balzano S, Gu HF, Andersen RA, Zingonea A. 2008. Global diversity and biogeography of Skeletonema species (Bacillariophyta). Protist 159, 177–193 10.1016/j.protis.2007.09.004 (doi:10.1016/j.protis.2007.09.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer AR, Gayron SD, Woodruff DS. 1990. Reproductive, morphological, and genetic evidence for two cryptic species of Northeastern Pacific Nucella. Veliger 33, 325–338 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klautau M, Russo CAM, Lazoski C, Boury-Esnault N, Thorpe JP, Sole-Cava AM. 1999. Does cosmopolitanism result from overconservative systematics? A case study using the marine sponge Chondrilla nucula. Evolution 53, 1414–1422 10.2307/2640888 (doi:10.2307/2640888) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakker FT, Olsen JL, Stam WT, Vandenhoek C. 1992. Nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS1 and ITS2) define discrete biogeographic groups in Cladophora albida (Chlorophyta). J. Phycol. 28, 839–845 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1992.00839.x (doi:10.1111/j.0022-3646.1992.00839.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palumbi SR, Metz EC. 1991. Strong reproductive isolation between closely related tropical sea urchins (genus Echinometra). Mol. Biol. Evol. 8, 227–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eble JA, Toonen RJ, Bowen BW. 2009. Endemism and dispersal: comparative phylogeography of three surgeonfishes across the Hawaiian Archipelago. Mar. Biol. 156, 689–698 10.1007/s00227-008-1119-4 (doi:10.1007/s00227-008-1119-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malay MCD, Paulay G. 2009. Peripatric speciation drives diversification and distributional pattern of reef hermit crabs (Decapoda: Diogenidae: Calcinus). Evolution 64, 634–662 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00848.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00848.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkendale LA, Meyer CP. 2004. Phylogeography of the Patelloida profunda group (Gastropoda : Lottidae): diversification in a dispersal-driven marine system. Mol. Ecol. 13, 2749–2762 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02284.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02284.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kisel Y, Barraclough TG. 2010. Speciation has a spatial scale that depends on levels of gene flow. Am. Nat. 175, 316–334 10.1086/650369 (doi:10.1086/650369) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paulay G, Meyer C. 2006. Dispersal and divergence across the greatest ocean region: do larvae matter? Integr. Comp. Biol. 46, 269–281 10.1093/icb/icj027 (doi:10.1093/icb/icj027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaines SD, Lester S, Eckert G, Kinlan B, Sagarin R, Gaylord B. 2009. Dispersal and geographic ranges in the sea. In Marine macroecology (eds Witman J, Roy K.), pp. 227–249 Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- 22.Claremont M, Williams ST, Barraclough TG, Reid DG. 2011. The geographic scale of speciation in a marine snail with high dispersal potential. J. Biogeogr. 38, 1016–1032 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02482.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02482.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cowie RH, Holland BS. 2006. Dispersal is fundamental to biogeography and the evolution of biodiversity on oceanic islands. J. Biogeogr. 33, 193–198 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01383.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01383.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowie RH, Holland BS. 2008. Molecular biogeography and diversification of the endemic terrestrial fauna of the Hawaiian Islands. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 363, 3363–3376 10.1098/rstb.2008.0061 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0061) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarnat EM, Moreau CS. 2011. Biogeography and morphological evolution in a Pacific island ant radiation. Mol. Ecol. 20, 114–130 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04916.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04916.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanks AL, Grantham BA, Carr MH. 2003. Propagule dispersal distance and the size and spacing of marine reserves. Ecol. Appl. 13, S159–S169 10.1890/1051-0761(2003)013[0159:PDDATS]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2003)013[0159:PDDATS]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinlan BP, Gaines SD. 2003. Propagule dispersal in marine and terrestrial environments: a community perspective. Ecology 84, 2007–2020 10.1890/01-0622 (doi:10.1890/01-0622) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchanan J, Zuccarello GC. 2012. Decoupling of short- and long-distance dispersal pathways in the endemic New Zealand seaweed Carpophyllum maschalocarpum (Phaeophyceae, Fucales). J. Phycol. 48, 518–529 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2012.01167.x (doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2012.01167.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neiva J, Pearson GA, Valero M, Serrao EA. 2012. Drifting fronds and drifting alleles: range dynamics, local dispersal and habitat isolation shape the population structure of the estuarine seaweed Fucus ceranoides. J. Biogeogr. 39, 1167–1178 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02670.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02670.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verbruggen H, Tyberghein L, Pauly K, Vlaeminck C, Van Nieuwenhuyze K, Kooistra W, Leliaert F, De Clerck O. 2009. Macroecology meets macroevolution: evolutionary niche dynamics in the seaweed Halimeda. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 18, 393–405 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00463.x (doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00463.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lüning K. 1990. Seaweeds: their environment, biogeography and ecophysiology. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brodie J, Andersen RA, Kawachi M, Millar AJK. 2009. Endangered algal species and how to protect them. Phycologia 48, 423–438 10.2216/09-21.1 (doi:10.2216/09-21.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuccarello GC, West JA. 2003. Multiple cryptic species: Molecular diversity and reproductive isolation in the Bostrychia radicans/B. moritziana complex (Rhodomelaceae, Rhodophyta) with focus on North American isolates. J. Phycol. 39, 948–959 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.02171.x (doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.02171.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saunders GW. 2005. Applying DNA barcoding to red macroalgae: a preliminary appraisal holds promise for future applications. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 360, 1879–1888 10.1098/rstb.2005.1719 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1719) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Clerck O, Gavio B, Fredericq S, Barbara I, Coppejans E. 2005. Systematics of Grateloupia filicina (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta), based on rbcL sequence analyses and morphological evidence, including the reinstatement of G. minima and the description of G. capensis sp. nov. J. Phycol. 41, 391–410 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.04189.x (doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.04189.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leliaert F, Verbruggen H, Wysor B, De Clerck O. 2009. DNA taxonomy in morphologically plastic taxa: Algorithmic species delimitation in the Boodlea complex (Chlorophyta: Cladophorales). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 53, 122–133 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.06.004 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2009.06.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robba L, Russell SJ, Barker GL, Brodie J. 2006. Assessing the use of the mitochondrial cox1 marker for use in DNA barcoding of red algae (Rhodophyta). Am. J. Bot. 93, 1101–1108 10.3732/ajb.93.8.1101 (doi:10.3732/ajb.93.8.1101) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Payo DA, Calumpong H, De Clerck O. 2011. Morphology, vegetative and reproductive development of the red alga Portieria hornemannii (Gigartinales: Rhizophyllidaceae). Aquat. Bot. 95, 94–102 10.1016/j.aquabot.2011.03.011 (doi:10.1016/j.aquabot.2011.03.011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Payo DA, Colo J, Calumpong H, de Clerck O. 2011. Variability of non-polar secondary metabolites in the red alga Portieria. Mar. Drugs 9, 2438–2468 10.3390/md9112438 (doi:10.3390/md9112438) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guiry MD, Guiry GM. 2012. AlgaeBase (searched on 10 January 2012). Galway, Ireland: World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland; See http://www.algaebase.org. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiseman DR. 1973. Morphological and taxonomic studies of the red algal genera Ochtodes and Chondrococcus. Durham, NC: Duke University [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masuda M, Kudo T, Kawaguchi S, Guiry MD. 1995. Lectotypification of some marine red algae described by W. H. Harvey from Japan. Phycol. Res. 43, 191–202 10.1111/j.1440-1835.1995.tb00025.x (doi:10.1111/j.1440-1835.1995.tb00025.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Clerck O, Bolton JJ, Anderson RJ, Coppejans E. 2005. Guide to the algae of Kwazulu-Natal. Scr. Bot. Belg. 33, 1–294 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carpenter KE, Springer VG. 2005. The center of the center of marine shore fish biodiversity: the Philippine Islands. Environ. Biol. Fishes 72, 467–480 10.1007/s10641-004-3154-4 (doi:10.1007/s10641-004-3154-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lermusiaux PFJ, Haley PJ, Jr, Leslie WG, Agarwal A, Logutov OG, Burton LJ. 2011. Multiscale physical and biological dynamics in the Philippine Archipelago: predictions and processes. Oceanography 24, 70–89 10.5670/oceanog.2011.05 (doi:10.5670/oceanog.2011.05) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melbourne-Thomas J, Johnson CR, Alino PM, Geronimo RC, Villanoy CL, Gurney GG. 2011. A multi-scale biophysical model to inform regional management of coral reefs in the western Philippines and South China Sea. Environ. Model. Softw. 26, 66–82 10.1016/j.envsoft.2010.03.033 (doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2010.03.033) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heaney LR, Walsh JS, Townsend Peterson A. 2005. The roles of geological history and colonization abilities in genetic differentiation between mammalian populations in the Philippine archipelago. J. Biogeogr. 32, 229–247 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2004.01120.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2004.01120.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones AW, Kennedy RS. 2008. Evolution in a tropical archipelago: comparative phylogeography of Philippine fauna and flora reveals complex patterns of colonization and diversification. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 95, 620–639 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01073.x (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01073.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 (doi:10.1093/nar/22.22.4673) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pons J, Barraclough TG, Gomez-Zurita J, Cardoso A, Duran DP, Hazell S, Kamoun S, Sumlin WD, Vogler AP. 2006. Sequence-based species delimitation for the DNA taxonomy of undescribed insects. Syst. Biol. 55, 595–609 10.1080/10635150600852011 (doi:10.1080/10635150600852011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monaghan MT, et al. 2009. Accelerated species inventory on Madagascar using coalescent-based models of species delineation. Syst. Biol. 58, 298–311 10.1093/sysbio/syp027 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syp027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. 2007. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 214. 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-214) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drummond AJ, Ho SYW, Phillips MJ, Rambaut A. 2006. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 4, 699–710 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. 2007. Tracer v. 1.4. See http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer.

- 55.R Core Team 2012. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; See http://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knowles LL, Carstens BC. 2007. Delimiting species without monophyletic gene trees. Syst. Biol. 56, 887–895 10.1080/10635150701701091 (doi:10.1080/10635150701701091) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niemiller ML, Near TJ, Fitzpatrick BM. 2012. Delimiting species using multilocus data: diagnosing cryptic diversity in the southern cavefish, Typhlichthys subterraneus (Teleostei: Amblyopsidae). Evolution 66, 846–866 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01480.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01480.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harrington RC, Near TJ. 2012. Phylogenetic and coalescent strategies of species delimitation in snubnose darters (Percidae: Etheostoma). Syst. Biol. 61, 63–79 10.1093/sysbio/syr077 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syr077) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roe AD, Rice AV, Bromilow SE, Cooke JEK, Sperling FAH. 2010. Multilocus species identification and fungal DNA barcoding: insights from blue stain fungal symbionts of the mountain pine beetle. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 946–959 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02844.x (doi:10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02844.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. 2003. MrBayes v. 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. 2008. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst. Biol. 57, 758–771 10.1080/10635150802429642 (doi:10.1080/10635150802429642) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dettman JR, Jacobson DJ, Taylor JW. 2003. A multilocus genealogical approach to phylogenetic species recognition in the model eukaryote Neurospora. Evolution 57, 2703–2720 10.1554/03-073 (doi:10.1554/03-073) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hudson RR, Coyne JA. 2002. Mathematical consequences of the genealogical species concept. Evolution 56, 1557–1565 10.1554/0014-3820(2002)056[1557:mcotgs]2.0.co;2 (doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2002)056[1557:mcotgs]2.0.co;2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang Z, Rannala B. 2010. Bayesian species delimitation using multilocus sequence data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9264–9269 10.1073/pnas.0913022107 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0913022107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heled J, Drummond AJ. 2010. Bayesian inference of species trees from multilocus data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 570–580 10.1093/molbev/msp274 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msp274) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leaché AD, Fujita MK. 2010. Bayesian species delimitation in west African forest geckos (Hemidactylus fasciatus). Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 3071–3077 10.1098/rspb.2010.0662 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0662) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zuccarello GC, West JA. 2002. Phylogeography of the Bostrychia calliptera-B-pinnata complex (Rhodomelaceae, Rhodophyta) and divergence rates based on nuclear, mitochondrial and plastid DNA markers. Phycologia 41, 49–60 10.2216/i0031-8884-41-1-49.1 (doi:10.2216/i0031-8884-41-1-49.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Andreakis N, Procaccini G, Maggs C, Kooistra W. 2007. Phylogeography of the invasive seaweed Asparagopsis (Bonnemaisoniales, Rhodophyta) reveals cryptic diversity. Mol. Ecol. 16, 2285–2299 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03306.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03306.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lessios HA. 2008. The great American schism: divergence of marine organisms after the rise of the Central American Isthmus. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 39, 63–91 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095815 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095815) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Frey MA, Vermeij GJ. 2008. Molecular phylogenies and historical biogeography of a circumtropical group of gastropods (Genus: Nerita): implications for regional diversity patterns in the marine tropics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 48, 1067–1086 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.05.009 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.05.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Colwell RK. 2009. EstimateS: statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples, v. 8.2. See http://purl.oclc.org/estimates

- 72.Dengler J. 2009. Which function describes the species–area relationship best? A review and empirical evaluation. J. Biogeogr. 36, 728–744 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.02038.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.02038.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Williams MR, Lamont BB, Henstridge JD. 2009. Species-area functions revisited. J. Biogeogr. 36, 1994–2004 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02110.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02110.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Silva PC, Meñez EG, Moe RL. 1987. Catalog of the benthic marine algae of the Philippines. Smithsonian Contributions to Marine Sciences 27, 1–179 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Avise JC, Wollenberg K. 1997. Phylogenetics and the origin of species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 7748–7755 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7748 (doi:10.1073/pnas.94.15.7748) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Richards V, Stanhope M, Shivji M. 2012. Island endemism, morphological stasis, and possible cryptic speciation in two coral reef, commensal Leucothoid amphipod species throughout Florida and the Caribbean. Biodivers. Conserv. 21, 343–361 10.1007/s10531-011-0186-x (doi:10.1007/s10531-011-0186-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rocha L, Craig M, Bowen B. 2007. Phylogeography and the conservation of coral reef fishes. Coral Reefs 26, 501–512 10.1007/s00338-007-0261-7 (doi:10.1007/s00338-007-0261-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Juinio-Menez MA, Magsino RM, Ravago-Gotanco R, Yu ET. 2003. Genetic structure of Linckia laevigata and Tridacna crocea populations in the Palawan shelf and shoal reefs. Mar. Biol. 142, 717–726 10.1007/s00227-002-0998-z (doi:10.1007/s00227-002-0998-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ravago-Gotanco RG, Juinio-Meñez MA. 2010. Phylogeography of the mottled spinefoot Siganus fuscescens: Pleistocene divergence and limited genetic connectivity across the Philippine archipelago. Mol. Ecol. 19, 4520–4534 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04803.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04803.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kool JT, Paris CB, Barber PH, Cowen RK. 2011. Connectivity and the development of population genetic structure in Indo-West Pacific coral reef communities. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 20, 695–706 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00637.x (doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00637.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.DeBoer TS, Subia MD, Erdmann MV, Kovitvongsa K, Barber PH. 2008. Phylogeography and limited genetic connectivity in the endangered boring giant clam across the Coral Triangle. Conserv. Biol. 22, 1255–1266 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00983.x (doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00983.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nuryanto A, Kochzius M. 2009. Highly restricted gene flow and deep evolutionary lineages in the giant clam Tridacna maxima. Coral Reefs 28, 607–619 10.1007/s00338-009-0483-y (doi:10.1007/s00338-009-0483-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Briggs JC. 2000. Centrifugal speciation and centres of origin. J. Biogeogr. 27, 1183–1188 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00459.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00459.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barber PH. 2009. The challenge of understanding the Coral Triangle biodiversity hotspot. J. Biogeogr. 36, 1845–1846 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02198.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02198.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Voris HK. 2000. Maps of Pleistocene sea levels in Southeast Asia: shorelines, river systems and time durations. J. Biogeogr. 27, 1153–1167 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00489.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00489.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Renema W, et al. 2008. Hopping hotspots: global shifts in marine biodiversity. Science 321, 654–657 10.1126/science.1155674 (doi:10.1126/science.1155674) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hall R. 2002. Cenozoic geological and plate tectonic evolution of SE Asia and the SW Pacific: computer-based reconstructions, model and animations. J. Asian Earth Sci. 20, 353–431 10.1016/S1367-9120(01)00069-4 (doi:10.1016/S1367-9120(01)00069-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Williams ST, Duda TF. 2008. Did tectonic activity stimulate Oligo-Miocene speciation in the Indo-West Pacific? Evolution 62, 1618–1634 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00399.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00399.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Weeks R, Russ GR, Alcala AC, White AT. 2010. Effectiveness of marine protected areas in the Philippines for biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Biol. 24, 531–540 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01340.x (doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01340.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J. 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858 10.1038/35002501 (doi:10.1038/35002501) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]