Abstract

Twenty years ago, scientists began to recognize that parental effects are one of the most important influences on progeny phenotype. Consequently, it was postulated that herbivorous insects could produce progeny that are acclimatized to the host plant experienced by the parents to improve progeny fitness, because host plants vary greatly in quality and quantity, and can thus provide important cues about the resources encountered by the next generation. However, despite the possible profound implications for our understanding of host-use evolution of herbivores, host-race formation and sympatric speciation, intense research has been unable to verify transgenerational acclimatization in herbivore–host plant relationships. We reared Coenonympha pamphilus larvae in the parental generation (P) on high- and low-quality host plants, and reared the offspring (F1) of both treatments again on high- and low-quality plants. We tested not only for maternal effects, as most previous studies, but also for paternal effects. Our results show that parents experiencing predictive cues on their host plant can indeed adjust progeny's phenotype to anticipated host plant quality. Maternal effects affected female and male offspring, whereas paternal effects affected only male progeny. We here verify, for the first time to our knowledge, the long postulated transgenerational acclimatization in an herbivore–host plant interaction.

Keywords: butterfly reproduction, larval feeding, Lepidoptera, maternal effects, paternal effects, phenotypic plasticity

1. Introduction

Over 20 years ago, scientists recognized parental effects as one of the most important influences on progeny phenotype with potential adaptive character [1,2] rather than as troublesome sources of variation in quantitative genetic studies [3]. Consequently, herbivorous insects experiencing predictive cues on their host plants have been expected to produce offspring that are physiologically acclimatized to particular host plant characteristics [4–7]. The acclimatized progeny would then benefit from parental host plant experience and improve their performance and hence increase fitness. This theoretically postulated process is termed transgenerational conditioning or acclimatization, the most obvious way that parental effects based on environmental conditions could influence progeny in an adaptive way [5,6]. But although several studies found adaptive maternal effects in plants [8–10], insects [2,11] and also in other animals [12–14], transgenerational acclimatization of progeny to host plants have not be documented so far, in spite of many experimental attempts [4–7,15–18]. This is surprising, because host plants provide a wealth of cues about the resource quality and quantity encountered by the next insect generation [6]. Because transgenerational acclimatization would also have important biological implications, Mousseau & Fox [19] stated that more work is required in this area. For instance, transgenerational acclimatization could reduce the costs of using a novel host over several generations, affecting the evolution of host range for an insect [6]. Furthermore, selection for host fidelity could be increased, possibly influencing host-use evolution of herbivores, host-race formation and sympatric speciation [5,6,11,19].

So far, there is only limited evidence from herbivorous insects that parental host plants could have substantial effects on progeny performance [7]. For example, it is known that insects can alter egg provisioning on the basis of maternal host plant experience and provide their progeny with increased resources for early larval development [20]. Pieris rapae females alter patterns of egg size and possibly egg provisioning based on nitrogen content in artificial diet, and offspring reared on the same nitrogen concentration as their mother had a higher larval mass at day four after eclosion [21]. However, after day four, this difference was no longer evident, and no positive effects on fitness could be detected thereafter [20]. There are also several other studies documenting adaptive maternal effects based on host plant experience, but these effects did not acclimatize offspring to specific anticipated host plant conditions [5,15,16]. For example, larvae of the seed beetle Stator limbatus whose mothers were reared on Pseudosamanea guachapele developed faster than offspring from mothers that were raised on Acacia greggii, regardless of whether progeny was reared on P. guachapele or A. greggii [16]. Thus, maternal experience did not adjust progeny phenotype to an anticipated host plant type, but affected offspring encountering any haphazard host plant type. Maternal effects therefore generally enhanced offspring performance, but this is not acclimatization to specific host plants, as the interaction between parental and progeny host plant effects was not significant. So far, only in the special case of aphids, which are thought to be particularly prone for transgenerational effects, because several generations are ‘telescoped’ within a developing aphid as embryos and may therefore be affected directly by the food of their mother or grandmother [6], was some evidence for transgenerational acclimatization found [22]. By contrast, other studies found no evidence for transgenerational acclimatization in aphids [4,7].

We reared Coenonympha pamphilus larvae in the parental generation (P) on nitrogen-rich (high-quality) and nitrogen-poor (low-quality) host plants, and reared the offspring (F1) of both treatments again on high- and low-quality plants. In two separate experiments, we tested whether males (P) and females (P) adjusted progeny performance to anticipated larval host conditions. Coenonympha pamphilus used in this study, as well as many other phytophagous insects, have to cope with varying host plant quality (high- versus low-nitrogen levels), nitrogen being a key nutrient for development and fitness in insects [23]. The nutritional quality experienced by the parental generation (P) could therefore prepare the progeny (F1) to optimally use the resources on similar nutritional plant quality and to improve performance and fitness.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study species

Coenonympha pamphilus L. (Lepidoptera: Satyrinae), the small heath, is a common butterfly in Eurasia and is found on various meadow types [24]. The larvae feed on a variety of grass species [25], differing in nutritional quality, but Festuca rubra is favoured [26]. Seven C. pamphilus females were collected from an unfertilized meadow in the northern Jura Mountains (Nenzlingen BL 47°26′ N, 7°33′ E, Switzerland). The eggs laid were sorted by maternal lineage and placed in separately marked Petri dishes.

(b). Host plants

Larval food plants of F. rubra were grown in 750 ml plastic pots filled with untreated calcareous soil from a nutrient-poor meadow near Liesberg BL in Switzerland. Each pot was planted with 450 seeds (UFA Samen, Basel, Switzerland). Plants were grown in a greenhouse at the University of Basel, with ambient sunlight in summer and supplement light (1000 W broad spectrum, light period from 6.00 to 20.00) during cloudy weather conditions and a day/night cycle of 25°C/19°C. High-quality larval food plants were fertilized once a week (N : P : K = 1 : 1 : 1). The low-quality larval food plants received only water. Plant nitrogen content was analysed from eight week old grass samples using a CHN analyser.

Silica is the main anti-herbivore defence in grasses and is more important than chemical defences in deterring herbivory on grasses [27,28]. Fertilization can slightly decrease the silica content in F. rubra, but this decrease in foliar silica content has no significant effect on larval performance in C. pamphilus [29].

(c). Larval rearing in the parental generation (P)

Larvae (P) descending from each of the seven wild-caught females were randomly divided into two groups, whereby one-half of the larvae was assigned to the high-quality host plants and the other half to the low-quality host plants. All lineages were included in the analysis. Larvae from different wild-caught females were reared separately in linegroups of 10 and kept singly in Petri dishes after two weeks. Light period was set from 6.00 to 20.00 with a day/night cycle of 25°C/19°C. Larvae reared on high-quality host plants (high-P) received high-quality host plants ad libitum in Petri dishes, whereas food quantity of last instar larvae of the parental generation raised on low-quality host plants (low-P) was limited to the amount ingested by high-P larvae. This approach was chosen to ensure low-nitrogen availability in low-P larvae, as we concentrated on effects of nitrogen supply in this study. In nature, C. pamphilus occurs in various meadow types and feeds on a variety of grass species differing greatly in nutritional quality [24–26]. Furthermore, high-silica content in low-quality host plants limits larval nitrogen acquisition [29], and low-nitrogen concentration in host plants can also cause compensatory feeding in C. pamphilus [29], resulting in underestimating effects of low-nitrogen supply [30].

To generate auxiliary butterflies for mating, additional larvae from the seven wild-caught females were reared on low-quality host plants fed ad libitum.

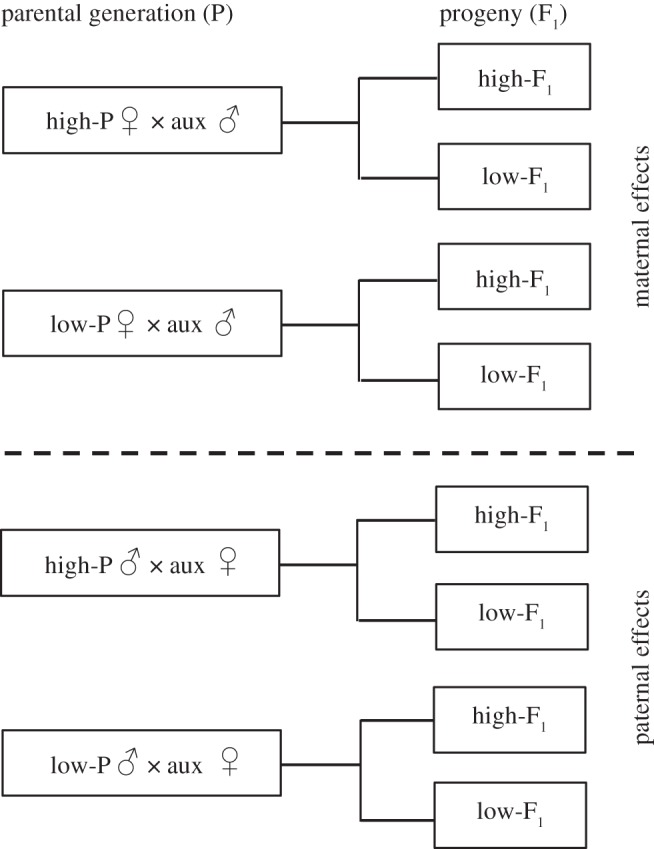

(d). Approach to test for maternal effects

We mated 12 high-P and 12 low-P females with auxiliary males to test for maternal effects. Twenty larvae (F1) from each mother were assigned randomly to the high- and low-quality plants (figure 1). All F1 larvae were fed ad libitum, allowing them to respond unconstrained to their respective diet. Female or male offspring (F1) from a single mother were pooled. We therefore obtained a sample size of n = 48 female offspring (F1) and n = 48 male offspring (F1), resulting in a total sample size of n = 96 to test for maternal effects.

Figure 1.

Experimental flow chart. Larvae of the parental generation (P) and their progeny (F1) were raised on high- and low-quality host plants. Adult butterflies of the parental generation were mated with auxiliary males or females (aux) reared on low-quality host plants and fed ad libitum. Progeny (F1) descending either from treated males or females (P) was treated and analysed separately.

(e). Approach to test for paternal effects

We mated 12 high-P and 12 low-P males with auxiliary females to test for paternal effects. Twenty larvae (F1) from each father were assigned randomly to the high- and low-quality plants (figure 1). All F1-larvae were fed ad libitum, allowing them to respond unconstrained to their respective diet. Female or male offspring (F1) from a single father were pooled. We therefore obtained a sample size of n = 47 female offspring (F1) and n = 47 male offspring (F1), resulting in a total sample size of n = 94 to test for paternal effects. The smaller sample size to test for paternal effects is owing to one damaged, low-quality pot from which the larvae escaped.

(f). Fitness parameters

We recorded larval hatching mass within 24 h (mg), and the fitness traits; larval duration (number of days from eclosion to pupation), pupal mass on the fifth day after pupation (mg) and forewing length within 24 h after emergence (mm; lateral wingspan of the left forewing). We measured larval hatching mass instead of egg mass because C. pamphilus females frequently laid their eggs on the cage netting, although larval host plants for oviposition were offered. Weighing eggs without destroying them was therefore difficult. However, previous studies with other butterfly species showed that egg mass and larval hatching mass are tightly correlated [31]. Thus, the measured larval hatching mass in this study is a good substitute for egg mass to assess parental provisioning to offspring. Larval duration was measured because prolonged larval duration may increase the exposure time to predators, parasites and other adverse factors [32,33]. Furthermore, pupal mass is an appropriate indicator for butterfly fitness, because male [34] and female [35] pupal mass is correlated with fecundity. We also measured forewing length because thorax mass and forewing geometry affect flight performance [36], which can be important for dispersal, foraging, reproduction and predator avoidance.

(g). Statistical analysis

Host plant nitrogen level and fitness traits in the parental generation (P) were analysed with two-sided t-tests. Fitness traits of progeny (F1) were analysed with mixed-effects models [37] with the categorical variables sex, host plant quality (P, F1) and the continuous variable larval hatching mass (F1). To account for inherited parental characteristics, the models testing for maternal effects also included the random factor maternal lineage [37] and the continuous covariates pupal mass or forewing length of untreated fathers, depending on the analysed fitness trait (table 1). The models testing for paternal effects additionally included the random factor paternal lineage [37] and the continuous covariates, pupal mass or forewing length of untreated mothers, depending on the analysed fitness trait (table 2). A stepwise model reduction was used, with the least significant interactions always removed first [37]. Larval duration and forewing length (F1) were analysed with generalized linear mixed-effects models owing to non-normal data structure [37,38]. Two-sided t-tests between pooled treatment groups (progeny reared on the same versus offspring reared on the opposite host plant quality from their parents) and Tukey multiple comparisons between unpooled treatment groups (high-P/high-F1, low-P/high-F1, high-P/low-F1, low-P/low-F1) were performed. Correlation analyses were used to test for relationships between fitness traits. All statistical analyses were two-sided and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

Effects of host plant quality of females of the parental generation (P) on progeny (F1) in Coenonympha pamphilus. (The effect size (r2), F-values, p-values and degrees of freedom (d.f.) are presented. Host plant quality (P, F1) is high-nitrogen versus low-nitrogen level. Females (P) were mated with unrelated auxiliary males (aux) fed ad libitum with low-quality host plants. r2 = F(F d.f.)−1. p-values <0.05 are bold. A stepwise model reduction of all models was used, with the least significant interactions always removed first [37].)

| larval duration (F1) |

pupal mass (F1) |

forewing length (F1) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | F | r2 | d.f. | p | F | r2 | d.f. | p | F | r2 | d.f. | |

| sex | <0.001 | 49.7 | 0.37 | 1,85 | <0.001 | 131.1 | 0.61 | 1,83 | <0.001 | 33.8 | 0.29 | 1,83 |

| host plant quality (F1) | <0.001 | 55.6 | 0.40 | 1,85 | 0.78 | 0.1 | 0.00 | 1,83 | 0.003 | 9.4 | 0.10 | 1,83 |

| host plant quality (P) | 0.20 | 1.7 | 0.02 | 1,85 | 0.41 | 0.7 | 0.01 | 1,83 | 0.012 | 6.6 | 0.07 | 1,83 |

| aux pupal mass (P) | 0.02 | 5.6 | 0.06 | 1,83 | ||||||||

| aux forewing length (P) | 0.008 | 7.4 | 0.08 | 1,83 | ||||||||

| maternal lineage | 0.33 | 1.6 | 0.19 | 1,5 | 0.03 | 8.3 | 0.62 | 1,5 | 0.77 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 1,5 |

| larval hatching mass (F1) | 0.31 | 1.0 | 0.01 | 1,85 | 0.61 | 0.3 | 0.00 | 1,83 | 0.56 | 0.3 | 0.00 | 1,83 |

| host plant quality (P) × host plant quality (F1) | <0.001 | 39.4 | 0.32 | 1,83 | <0.001 | 15.6 | 0.16 | 1,83 | ||||

Table 2.

Effects of host plant quality of males of the parental generation (P) on progeny (F1) in Coenonympha pamphilus. (The effect size (r2), F values, p-values and degrees of freedom (d.f.) are presented. Host plant quality (P, F1) is high-nitrogen versus low-nitrogen level. Males (P) were mated with unrelated auxiliary females (aux) fed ad libitum with low-quality host plants. r2 = F(F df)−1. p-values <0.05 are bold. A stepwise model reduction of all models was used, with the least significant interactions always removed first [37].)

| larval duration (F1) |

pupal mass (F1) |

forewing length (F1) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | F | r2 | d.f. | p | F | r2 | d.f. | p | F | r2 | d.f. | |

| sex | <0.001 | 71.2 | 0.46 | 1,82 | <0.001 | 115.2 | 0.59 | 1,81 | <0.001 | 42.7 | 0.35 | 1,80 |

| host plant quality (F1) | <0.001 | 14.8 | 0.15 | 1,82 | 0.13 | 2.4 | 0.03 | 1,81 | 0.20 | 1.7 | 0.02 | 1,80 |

| host plant quality (P) | 0.027 | 5.1 | 0.06 | 1,82 | 0.50 | 0.5 | 0.01 | 1,81 | 0.09 | 3.0 | 0.04 | 1,80 |

| aux pupal mass (P) | 0.01 | 7.6 | 0.09 | 1,81 | ||||||||

| aux forewing length (P) | <0.001 | 12.6 | 0.14 | 1,80 | ||||||||

| paternal lineage | 0.72 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 1,5 | 0.09 | 4.3 | 0.46 | 1,5 | 0.13 | 3.3 | 0.40 | 1,5 |

| larval hatching mass (F1) | 0.032 | 4.8 | 0.05 | 1,82 | 0.17 | 1.9 | 0.02 | 1,81 | 0.19 | 1.8 | 0.02 | 1,80 |

| host plant quality (P) × host plant quality (F1) | 0.01 | 6.6 | 0.07 | 1,82 | 0.04 | 4.5 | 0.05 | 1,81 | 0.02 | 5.7 | 0.04 | 1,80 |

3. Results

(a). Host plant quality

Fertilized F. rubra host plants (3.16 ± 0.05 g nitrogen per gram dry weight) had significantly higher leaf nitrogen content than unfertilized host plants (1.67 ± 0.09 g nitrogen per gram dry weight; t = 15.2, n = 16, p < 0.001).

(b). Parental generation

Females as well as males (P) reared on high-quality host plants had a significantly shorter larval duration (females: high-quality 24.67 ± 0.64 days; low-quality 38.78 ± 1.42 days; t = 9.1, n = 24, p < 0.001; males: high-quality 21.23 ± 0.67 days; low-quality 30.46 ± 0.92 days; t = 8.2, n = 24, p < 0.001), higher pupal mass (females: high-quality 67.62 ± 1.44 mg; low-quality 45.79 ± 1.17 mg; t = 11.8, n = 24, p < 0.001; males: high-quality 51.69 ± 1.07 mg; low-quality 37.17 ± 0.78 mg; t = 10.9, n = 24, p < 0.001) and longer forewings (females: high-quality 13.11 ± 0.16 mm; low-quality 10.89 ± 0.14 mm; t = 10.6, n = 24, p < 0.001; males: high-quality 12.56 ± 0.14 mm; low-quality 10.36 ± 0.14 mm; t = 8.4, n = 24, p < 0.001) than females and males raised on low-quality host plants.

(c). Effects of maternal experience on progeny performance

Larval duration (F1) was significantly affected by sex and host plant quality (F1), whereas host plant quality of mothers (P), maternal lineage and larval hatching mass had no significant effects (table 1). Larvae reared on high-quality host plants developed faster (females: 25.66 ± 0.43 days; males: 21.51 ± 0.47 days) than larvae raised on low-quality host plants (females: 31.39 ± 1.05 days; t = 5.5, n = 48, p < 0.001; males: 25.87 ± 0.87 days; t = 4.6, n = 47, p < 0.001), irrespective of maternal host plant quality.

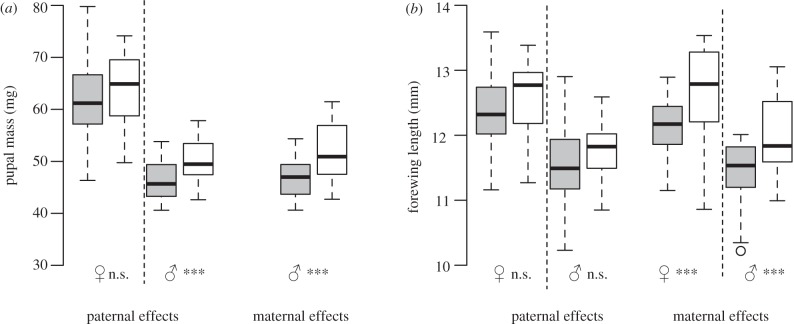

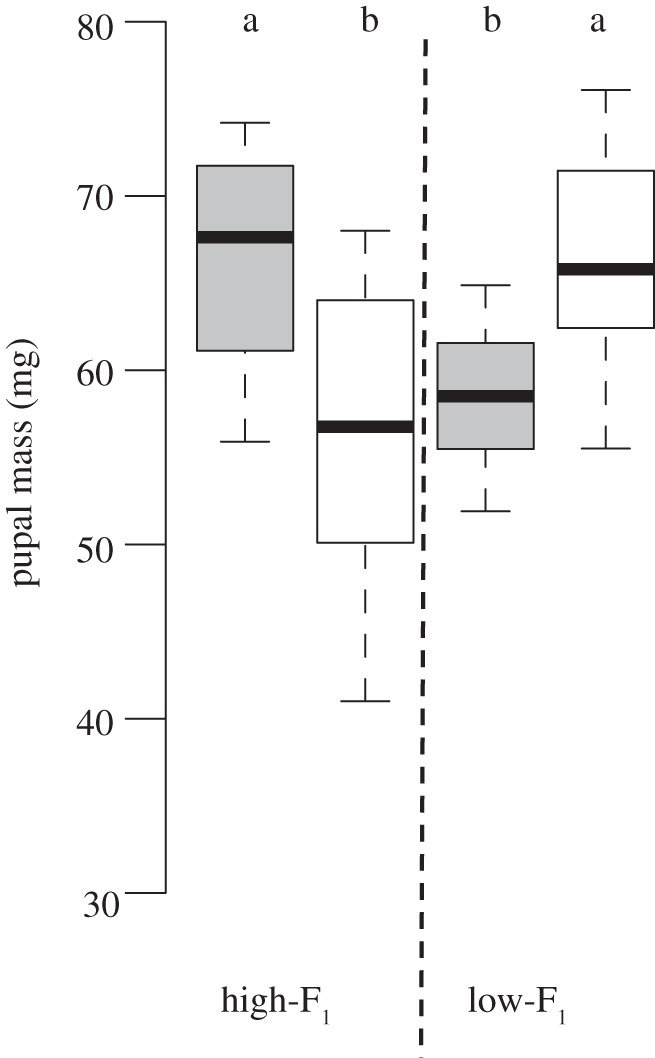

Pupal mass (F1) was significantly affected by sex, maternal lineage and pupal mass of untreated fathers (P), whereas host plant quality (maternal, F1) and larval hatching mass had no significant effects (table 1). There was a significant maternal–host-by-progeny–host interaction (table 1). High-P/high-F1 and low-P/low-F1 females had a significantly higher pupal mass than low-P/high-F1 and high-P/low-F1 females (figure 2). Pupal mass of male offspring was affected less clearly by maternal experience, but pooled male progeny reared on the same (low-P/low-F1 plus high-P/high-F1) rather than the opposite (low-P/high-F1 plus high-P/low-F1) host plant quality as their mother had a higher pupal mass (t = 3.48, n = 48, p = 0.001; figure 3a). Larval duration and pupal mass did not significantly correlate (females: r2 = 0.02, n = 48, p = 0.39; males: r2 = 0.00, n = 48, p = 0.73).

Figure 2.

Pupal mass of Coenonympha pamphilus females (F1). Progeny (high-F1 versus low-F1) was raised on high- and low-quality host plants and descended from mothers (high-P versus low-P) reared on high- (grey bars) and low-quality (white bars) host plants. The box represents the interquartile range from first to third quartile; the line across the box indicates the median, and the whiskers show maximum and minimum values. Different alphabets indicate significant differences between treatment groups (Tukey multiple comparison, p < 0.05, offspring descending from a single mother were pooled, see §2, n = 12 for each treatment group).

Figure 3.

(a) Pupal mass and (b) forewing length of Coenonympha pamphilus males and females of the F1 generation descending from males and females (P). Progeny was raised on high- and low-quality host plants and descended from mothers (maternal effects) or fathers (paternal effects) reared on high- and low-quality host plants. The box represents the interquartile range from first to third quartile; the line across the box indicates the median, and the whiskers show maximum and minimum values; asterisks indicate statistical differences between larvae reared on the same (white bars) and the opposite (grey bars) host plant quality as their father or mother (n.s.p > 0.05, ***p < 0.001, two-sided t-test, offspring descending from a single mother or father were pooled, see §2, n = 24 for each treatment group, except for groups reared on the same host plants as their father n = 23 for each treatment group). Data for pupal mass of females (F1) descending from mothers (P) are shown in figure 2.

Forewing length (F1) was significantly affected by sex, host plant quality (maternal, F1) and forewing length of untreated fathers (P), whereas maternal lineage and larval hatching mass had no significant effects (table 1). There was a significant maternal–host-by-progeny–host interaction (table 1). Pooled progeny reared on the same (low-P/low-F1, plus high-P/high-F1) rather than the opposite (low-P/high-F1, plus high-P/low-F1) host plant quality as their mother had significantly longer forewings (females: t = 3.1, n = 48, p = 0.004; males: t = 3.1, n = 48, p = 0.003; figure 3b). Pupal mass and forewing length were positively correlated (females: r2 = 0.81, n = 48, p < 0.001; males: r2 = 0.86, n = 48, p < 0.001).

(d). Effects of paternal experience on progeny performance

Larval duration (F1) was significantly affected by sex, host plant quality (paternal, F1) as well by larval hatching mass, whereas paternal lineage had no significant effect (table 2). Larvae reared on high-quality host plants developed faster (females: 25.66 ± 0.43 days; males: 21.51 ± 0.47 days) than larvae raised on low-quality host plants (females: 30.12 ± 0.73 days; t = 5.5, n = 48, p < 0.001; males: 25.24 ± 0.59 days; t = 4.6, n = 47, p < 0.001), irrespective of paternal host plant quality. Furthermore, low-P/low-F1 females developed faster (28.33 ± 0.97 days) than high-P/low-F1 females (31.58 ± 0.85 days; Tukey multiple comparison: p = 0.03), causing a significant paternal–host-by-progeny–host interaction (table 2).

Pupal mass (F1) was significantly affected by sex and pupal mass of untreated mothers (P), whereas host plant quality (paternal, F1) and larval hatching mass had no significant effects (table 2). Paternal lineage had a marginal effect (table 2). There was a significant paternal–host-by-progeny–host interaction (table 2). Pupal mass of pooled male progeny reared on the same (low-P/low-F1 plus high-P/high-F1) rather than the opposite (low-P/high-F1 plus high-P/low-F1) host plant quality as their fathers was significantly higher in male offspring (t = 2.4, n = 47, p = 0.02), whereas there was no significant difference in pooled female progeny (t = 0.9, n = 47, p = 0.36; figure 3a). Larval duration and pupal mass did not significantly correlate (females: r2 = 0.13, n = 47, p = 0.37; males: r2 = 0.17, n = 47, p = 0.26).

Forewing length (F1) was significantly affected by sex and forewing length of untreated females (P), whereas paternal lineage, larval hatching mass and host plant quality (F1) had no significant effects (table 2). Larval host quality of fathers had a marginal effect (table 2). There was a significant paternal–host-by-progeny–host interaction (table 2). However, forewing length did not differ significantly between pooled progeny reared on the same (low-P/low-F1 plus high-P/high-F1) rather than the opposite (low-P/high-F1 plus high-P/low-F1) host plant quality as their father (females: t = 0.9, n = 47, p = 0.35; males: t = 1.7, n = 47, p = 0.10; figure 3b). Pupal mass and forewing length were positively correlated (females: r2 = 0.88, n = 47, p < 0.001; males: r2 = 0.66, n = 47, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

(a). Maternal experience

Progeny reared on the same (low-P/low-F1, high-P/high-F1) rather than the opposite (low-P/high-F1, high-P/low-F1) host plant quality as their mother performed significantly better (figures 2 and 3; table 1). This clearly shows that mothers acclimatized their progeny to the anticipated host plant quality. Highly significant maternal–host-by-progeny–host interactions emphasized these findings (table 1). Without transgenerational acclimatization, our results should have shown the negative effects of nitrogen-poor larval food on all low-F1 larvae, because high-P parents had a higher pupal mass and forewing length than low-P parents. However, the nitrogen-poor larval food had no negative effects on low-P/low-F1 larvae, and low-P/low-F1 females performed also better than high-P/low-F1 females. Our results show not only that low-P/low-F1 larvae can compensate for low-quality larval food owing to maternal experience, but also that the high-P/high-F1 females performed significantly better than the low-P/high-F1 females, although both groups were raised on nitrogen-rich host plants. Furthermore, contrary to intuition, low-P/low-F1 larvae achieved the same pupal mass as high-P/high-F1 larvae, and low-P/low-F1 females even had a higher pupal mass than low-P/high-F1 females, despite the low-nitrogen content in low-quality host plants. Obviously, mothers adjusted the ability of their progeny's food intake or efficiency of larval nitrogen use according to their own experienced host plant quality, thereby adjusting their progeny also to the anticipated future host plant quality encountered by their offspring. Thus, maternal experience primarily determined larval performance in our experiment. By contrast, other studies that attempted to show transgenerational acclimatization often found strong effects of the progeny's immediate host plant instead of transgenerational acclimatization owing to parental experience [4,6,7,16,17].

Furthermore, pupal mass of female offspring was more strongly affected by maternal transgenerational acclimatization than pupal mass of male progeny, as can be seen in the distinct difference between treatment groups (figures 2 and 3a). Pupal mass of males (F1) either was less variable than female pupal mass, because C. pamphilus males are generally smaller than females and may have a smaller range to vary their pupal mass, or maternal experience was more strongly mediated within the same sex than from females (P) to males (F1).

(b). Paternal experience

While maternal effects are widely recognized as important contributors to offspring phenotypes, transgenerational acclimatization to host plants based on paternal experience has been little studied [5,15]. However, many insects have a mating system in which males transfer nutrients and other chemical compounds such as hormones and enzymes to females at mating, which may affect reproduction and accordingly offspring [39,40]. Experiments to find transgenerational acclimatization in S. limbatus beetles showed symmetry between the magnitude of paternal and maternal host effects on survivorship of progeny [5]. In our study, similar to maternal effects, paternal host quality experience increased pupal mass of male offspring reared on the same host quality as their fathers (figure 3a). However, in contrast to male offspring, paternal experience had no detectable effect on female progeny (figure 3), and paternal effects were weaker than maternal effects (tables 1 and 2). This suggests that maternal effects are generally more important than paternal effects. However, paternal experience could compensate for the limited effect of maternal experience on male progeny, as the expression of genes or chromosomes can depend on the sex through which the chromosome is transmitted [41]. Correspondingly, maternal and paternal effects of Ophraella notulata beetles reared on different host plants were not independent of each other, but transgenerational acclimatization was not found in that species [15].

(c). Biological implications

Previous studies that have attempted to show transgenerational acclimatization found only direct effects of progeny host [4,6,7,16,17] or parental effects independent from progeny's rearing host on offspring performance [5,15,16,18]. Transgenerational acclimatization to host plants possibly occurs primarily within a host species rather than between different host species with differing chemical and physiological attributes. This is supported by a hint for transgenerational acclimatization found in P. rapae females, which were reared on artificial diets differing only in nitrogen concentration [21]. Females altered patterns of egg size and possibly egg provisioning based on their food quality and influenced progeny, even though only early during its development and without ultimate positive effects on fitness [21].

Of course we cannot neglect the general role of random genetic inheritance, as lineage and maternal and paternal characteristics of the auxiliary parental mating partners also significantly affected progeny (tables 1 and 2). Adaptive maternal effects and genetic inheritance act together [5]. Genetic fixation of a trait is appropriate in stable environments with a constant quantity and quality of resources, but resource-based transgenerational acclimatization is favourable for quick adaptation from one generation to the next. For example, host plant quality can vary over time, and when host plant quality changes with a higher rate than genetic adaptation to altered host conditions occurs in herbivores, transgenerational acclimatization could enable temporary adaptation to the altered host plant quality. Furthermore, C. pamphilus lives on spatially patchy distributed meadow types and small fragmented habitats, all differing considerably in nutritional quality [24,25]. In addition, C. pamphilus males often reproduce in restricted territories [42], and mated females are relatively immobile and often walk on the ground for oviposition instead of flying long distances [43]. It is therefore likely that offspring develop within the same patch and accordingly on the same host plant quality as their parents. Thus, transgenerational acclimatization may enhance local adaptation to greatly diverse habitats of C. pamphilus. Clearly, transgenerational acclimatization is of immense ecological interest, because improved adaptation of an organism to its resources increases its fitness. This, in turn, influences population size and mortality, and finally even alters the dynamics of entire populations [44].

Coenonympha pamphilus females as well as females of other Satyrid butterflies often do not discriminate between oviposition sites [45], presumably because they reproduce within spatially restricted habitats with a consistent host plant quality. By contrast, oviposition choice could be an important factor for transgenerational acclimatization in other insect species, because acclimatized progeny located on a different host plant quality as their parents suffers from decreased fitness (figures 2 and 3). Contrary to intuition, low-P females should therefore oviposit on low-quality host plants rather than on high-quality plants. Several theories, such as the ‘Hopkins host selection principle’ [46], the ‘neo-Hopkins principle’ [47] and ‘chemical legacy’ [48], actually suggest that maternal host plants can influence oviposition choice, but evidence for this effect is controversial [49–51]. If females lay their eggs indeed on the same host plant type they were acclimatized to and on which they acclimatize their progeny, host-race formation could be influenced when correlations between oviposition choices and larval performance are maintained in a randomly mating population through maternal host experience [5]. Such interactions could result in a runaway process that facilitates sympatric speciation in systems where oviposition choices determine the environment for offspring development [52,53]. Divergent host plant use can also cause assortative mating by phenotypically altering traits involved in mate recognition. For instance, male mustard leaf beetles Phaedon cochleariae preferred to mate with females reared on the same rather than a different host plant species [54].

Transgenerational acclimatization to host plants in herbivorous insects was postulated for a long time, but has not been shown to date, despite intense research and its profound implications for ecological and evolutionary processes [6,7]. This process, verified, to our knowledge, for the first time in this study, requires more investigation in other insect–host plant interactions, because transgenerational acclimatization could generally affect the coexistence between plants and insects, two of the most diverse groups of living organisms united by intricate relationships.

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Mevi-Schütz, P. Stoll, D. Aydin, R. Cahenzli and E. Nikles for their valuable comments; H. Heesterbeek, S. Renner, M. Singer and an anonymous referee for their helpful reviews of the manuscript; Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft Basel, Basler Stiftung für biologische Forschung and Emilia Guggenheim-Schnurr Stiftung for the financial support and C. Körner for use of the greenhouse. This work is supported by the Fonds zur Förderung des akademischen Nachwuchses der Universität Basel (project no. 65051 to A.E.).

References

- 1.Kirkpatrick M, Lande R. 1989. The evolution of maternal characters. Evolution 43, 485–503 10.2307/2409054 (doi:10.2307/2409054) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mousseau TA, Dingle H. 1991. Maternal effects in insect life histories. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 36, 511–534 10.1146/annurev.ento.36.1.511 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.36.1.511) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falconer DS. 1981. Introduction to quantitative genetics. London, UK: Longman [Google Scholar]

- 4.Via S. 1991. Specialized host plant performance of pea aphid clones is not altered by experience. Ecology 72, 1420–1427 10.2307/1941114 (doi:10.2307/1941114) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox CW, Waddell KJ, Mousseau TA. 1995. Parental host plant affects offspring life histories in a seed beetle. Ecology 76, 402–411 10.2307/1941199 (doi:10.2307/1941199) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spitzer BW. 2004. Maternal effects in the soft scale insect Saissetia coffeae (Hemiptera: Coccidae). Evolution 58, 2452–2461 10.1554/03-642 (doi:10.1554/03-642) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mc Lean AC, Ferrari J, Godfray HJC. 2009. Effects of the maternal and pre-adult host plant on adult performance and preference in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum . Ecol. Entomol. 34, 330–338 10.1111/j.1365-2311.2008.01081.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2008.01081.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galloway LF, Etterson JR. 2007. Transgenerational plasticity is adaptive in the wild. Science 318, 1134–1136 10.1126/science.1148766 (doi:10.1126/science.1148766) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sultan SE, Barton K, Wilczek AM. 2009. Contrasting patterns of transgenerational plasticity in ecologically distinct congeners. Ecology 90, 1831–1839 10.1890/08-1064.1 (doi:10.1890/08-1064.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whittle CA, Otto SP, Johnston MO, Krochko JE. 2009. Adaptive epigenetic memory of ancestral temperature regime in Arabidopsis thaliana. Botany 87, 650–657 10.1139/B09-030 (doi:10.1139/B09-030) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mousseau TA, Fox CW. 1998. Maternal effects as adaptations. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoder JA, Tank JL, Rellinger EJ. 2006. Evidence of a maternal effect that protects against water stress in larvae of the American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Insect Physiol. 52, 1034–1042 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2006.07.002 (doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2006.07.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgess SC, Marshall DJ. 2011. Temperature-induced maternal effects and environmental predictability. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 2329–2336 10.1242/jeb.054718 (doi:10.1242/jeb.054718) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salinas S, Munch SB. 2012. Thermal legacies: transgenerational effects of temperature on growth in a vertebrate. Ecol. Lett. 15, 159–163 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01721.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01721.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Futuyma DJ, Herman C, Milstein S, Keese MC. 1993. Apparent transgenerational effects of host-plant in the leaf beetle Ophraella notulata (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae). Oecologia 96, 365–372 10.1007/BF00317507 (doi:10.1007/BF00317507) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amarillo-Suarez AR, Fox CW. 2006. Population differences in host use by a seed-beetle: local adaptation, phenotypic plasticity and maternal effects. Oecologia 150, 247–258 10.1007/s00442-006-0516-y (doi:10.1007/s00442-006-0516-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Or K, Ward D. 2007. Maternal effects on the life histories of bruchid beetles infesting Acacia raddiana in the Negev desert, Israel. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 122, 165–170 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2006.00509.x (doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.2006.00509.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox CW. 1997. The ecology of body size in a seed beetle, Stator limbatus: persistence of environmental variation across generations? Evolution 51, 1005–1010 10.2307/2411176 (doi:10.2307/2411176) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mousseau TA, Fox CW. 1998. The adaptive significance of maternal effects. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 403–407 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01472-4 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01472-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Awmack CS, Leather SR. 2002. Host plant quality and fecundity in herbivorous insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 47, 817–844 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145300 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145300) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rotem K, Agrawal AA, Kott L. 2003. Parental effects in Pieris rapae in response to variation in food quality: adaptive plasticity across generations? Ecol. Entomol. 28, 211–218 10.1046/j.1365-2311.2003.00507.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2311.2003.00507.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Barro PJ, Sherratt TN, David O, MacLean M. 1995. An investigation of the differential performance of clones of the aphid Sitobion avenae on two host species. Oecologia 104, 379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoonhoven LM, Van Loon JJA, Dicke M. 2006. Insect: plant biology, 2nd edn Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lepidopterologen-Arbeitsgruppe 1987. Tagfalter und ihre Lebensräume, Band 1. Basel, Switzerland: Schweizerischer Bund für Naturschutz [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koch M. 1991. Schmetterlinge. Radebeul, Germany: Neumann [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goverde M, Erhardt A. 2003. Effects of elevated CO2 on development and larval food-plant preference in the butterfly Coenonympha pamphilus (Lepidoptera, Satyridae). Glob. Change Biol. 9, 74–83 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00520.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00520.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vicari M, Bazely DR. 1993. Do grasses fight back: the case for antiherbivore defenses. Trends Ecol. Evol. 8, 137–141 10.1016/0169-5347(93)90026-L (doi:10.1016/0169-5347(93)90026-L) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massey FP, Ennos AR, Hartley SE. 2007. Grasses and the resource availability hypothesis: the importance of silica-based defences. J. Ecol. 95, 414–424 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01223.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01223.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cahenzli F, Erhardt A. 2012. Host plant defence in the larval stage affects feeding behaviour in adult butterflies. Anim. Behav. 84, 995–1000 10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.07.025 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.07.025) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carvalho GB, Kapahi P, Benzer S. 2005. Compensatory ingestion upon dietary restriction in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Methods 2, 813–815 10.1038/NMETH798 (doi:10.1038/NMETH798) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karlsson B, Wiklund C. 1984. Egg weight variation and lack of correlation between egg weight and offspring fitness in the wall brown butterfly, Lasiommata megera. Oikos 43, 376–385 10.2307/3544156 (doi:10.2307/3544156) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clancy KM, Price PW. 1987. Rapid herbivore growth enhances enemy attack: sublethal plant defenses remain a paradox. Ecology 68, 733–737 10.2307/1938479 (doi:10.2307/1938479) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams IS. 1999. Slow-growth, high-mortality: a general hypothesis, or is it? Ecol. Entomol. 24, 490–495 10.1046/j.1365-2311.1999.00217.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2311.1999.00217.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferkau C, Fischer K. 2006. Costs of reproduction in male Bicyclus anynana and Pieris napi butterflies: effects of mating history and food limitation. Ethology 112, 1117–1127 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01266.x (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01266.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cahenzli F, Erhardt A. 2012. Nectar sugars enhance fitness in male Coenonympha pamphilus butterflies by increasing longevity or realized reproduction. Oikos 121, 1417–1427 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2012.20190.x (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2012.20190.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berwaerts K, Van Dyck H, Aerts P. 2002. Does flight morphology relate to flight performance? An experimental test with the butterfly Pararge aegeria. Funct. Ecol. 16, 484–491 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00650.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00650.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crawley MJ. 2007. The R book. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinheiro JC, Bates DM. 2000. Mixed effects-models in S and S-plus. Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bissoondath CJ, Wiklund C. 1996. Male butterfly investment in successive ejaculates in relation to mating system. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 39, 285–292 10.1007/s002650050291 (doi:10.1007/s002650050291) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cahenzli F, Erhardt A. 2013. Nectar amino acids enhance reproduction in male butterflies. Oecologia 171, 197–205 10.1007/s00442-012-2395-8 (doi:10.1007/s00442-012-2395-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jablonka E, Lamb MJ. 1989. The inheritance of acquired epigenetic variations. J. Theor. Biol. 139, 69–83 10.1016/S0022-5193(89)80058-X (doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(89)80058-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wickman P-O. 1985. Territorial defence and mating success in males of the small heath butterfly Coenonympha pamphilus L. Anim. Behav. 33, 1162–1168 10.1016/S0003-3472(85)80176-7 (doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(85)80176-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wickman P-O. 1986. Courtship solicitation by females of the small heath butterfly, Coenonympha pamphilus (L.) (Lepidoptera: Satyridae) and their behaviour in relation to male territories before and after copulation. Anim. Behav. 34, 153–157 10.1016/0003-3472(86)90017-5 (doi:10.1016/0003-3472(86)90017-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossiter MC. 1991. Environmentally-based maternal effects: a hidden force in insect population dynamics? Oecologia 7, 288–294 10.1007/BF00325268 (doi:10.1007/BF00325268) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiklund C, Karlsson B. 1984. Egg size variation in Satyrid butterflies: adaptive vs historical, ‘Bauplan’, and mechanistic explanations. Oikos 43, 391–400 10.2307/3544158 (doi:10.2307/3544158) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hopkins AD. 1917. A discussion of H.G. Hewitt's paper on ‘Insect behavior’. J. Econ. Entomol. 10, 92–93 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaenike J. 1983. Induction of host preference in Drosophila melanogaster. Oecologia 58, 320–325 10.1007/BF00385230 (doi:10.1007/BF00385230) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corbet SA. 1985. Insect chemosensory responses: a chemical legacy hypothesis. Ecol. Entomol. 10, 143–153 10.1111/j.1365-2311.1985.tb00543.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1985.tb00543.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Janz N, Söderlind L, Nylin S. 2009. No effect of larval experience on adult host preferences in Polygonia c-album (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae): on the persistence of Hopkin's host selection principle. Ecol. Entomol. 34, 50–57 10.1111/j.1365-2311.2008.01041.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2008.01041.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Facknath S, Wright DJ. 2007. Is host selection in leafminer adults influenced by preimaginal or early adult experience? J. Appl. Entomol. 131, 505–512 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2007.01195.x (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0418.2007.01195.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barron AB. 2001. The life and death of Hopkins’ host-selection principle. J. Insect Behav. 14, 725–737 10.1023/A:1013033332535 (doi:10.1023/A:1013033332535) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diehl S, Bush GL. 1989. Speciation and its consequences. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates Inc [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wade MJ. 1998. The evolutionary genetics of maternal effects. In Maternal effects as adaptations (eds Mousseau TA, Fox CW.), pp. 5–21 New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geiselhardt S, Otte T, Hilker M. 2012. Looking for a similar partner: host plants shape mating preferences of herbivorous insects by altering their contact pheromones. Ecol. Lett. 15, 971–977 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01816.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01816.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]