Abstract

The rate by which new mutations are introduced into a population may have far-reaching implications for processes at the population level. Theory assumes that all individuals within a population have the same mutation rate, but this assumption may not be true. Compared with individuals in high condition, those in poor condition may have fewer resources available to invest in DNA repair, resulting in elevated mutation rates. Alternatively, environmentally induced stress can result in increased investment in DNA repair at the expense of reproduction. Here, we directly test whether sexual harassment by males, known to reduce female condition, affects female capacity to alleviate DNA damage in Drosophila melanogaster fruitflies. Female gametes can repair double-strand DNA breaks in sperm, which allows manipulating mutation rate independently from female condition. We show that male harassment strongly not only reduces female fecundity, but also reduces the yield of dominant lethal mutations, supporting the hypothesis that stressed organisms invest relatively more in repair mechanisms. We discuss our results in the light of previous research and suggest that social effects such as density and courtship can play an important and underappreciated role in mediating condition-dependent mutation rate.

Keywords: hormesis, mutation rate, sexual conflict, sexual selection

1. Introduction

Mutations are the ultimate source of genetic variation and the frequency by which they occur is at the heart of evolutionary diversification and population viability. The genome-wide mutation rate per individual and generation, U, is a key parameter in population genetics, which has been used extensively in many theoretical models in evolutionary biology [1–4]. The mutation rate has generally been assumed to be fixed across individuals within populations [5], although it has been speculated that an increased mutation rate could be an adaptive response of a genotype exposed to an unfavourable environment [6]. Nevertheless, several early studies hinted at the possibility that individual mutation rate can depend on the genotype or the physiological condition of the individual [7]. Thus, experiments using the fruitfly, Drosophila melanogaster, suggested that female repair of induced mutagenesis in spermatozoa prior to fertilization may be influenced by temperature [8], infrared irradiation of eggs [9], diet [10,11], antibiotics [12] and female genotype [13].

Recent experiments further show that the mutation rate may vary between individuals within a population, depending on their condition. These results primarily come from experiments with unicellular organisms [14,15], but three recent studies of D. melanogaster indicate that the mutation rate may be dependent on condition also in multicellular organisms. In one study, the genetic quality was manipulated by allowing one population of flies to accumulate more deleterious mutations compared with another population [16]. It was subsequently shown that flies derived from the mutation–accumulation population had a higher rate of decrease in viability consistent with an accelerated mutation rate with genetic load [16], or alternatively with an increased deleterious effect of mutations as a function of genetic load [17]. In another study, the authors manipulated the nutritional value of larval diet to create adult female flies that differed markedly in their condition [18]. In this study, the mutation yield of sex-linked recessive lethals was higher in low-condition flies [18]. Finally, Sharp & Agrawal [19] experimentally showed that low-quality genotypes suffer from elevated mutation rates, leading to positive mutational feedback.

Why would individual condition have an effect on individual mutation rate and what kind of effect? It has been hypothesized that individuals in poor condition will have fewer resources to invest in DNA repair, resulting in higher mutation rates [17–19]. Such a mechanism would have far-reaching implications for the fate of the population, suggesting that populations suffering from increased mutation load will be prone to accumulating germline mutations at an ever increasing rate [17,19]. Similarly, populations experiencing adverse environmental conditions would be more likely to produce mutation-ridden progeny. Finally, such a process would have implications for sexual selection because it would increase the cost of mating with a low-condition mate [18,20]. Nevertheless, an opposing argument can be made that condition-reducing environmental stress would increase investment in somatic maintenance, including DNA repair, at the expense of investment in reproduction.

Trade-offs between investment in reproduction and somatic maintenance, including DNA repair, may change considerably with condition, so that relatively more resources could be directed towards repair when individuals are in low condition [21,22]. For example, dietary restriction (DR) is the prime environmental intervention that increases lifespan in a wide variety of taxa from yeast to fruitflies to mammals [23–27]. Consequently, DR has been associated with reduced levels of somatic mutations in mice [28], although not in D. melanogaster [29]. Theory suggests that diversion of resources from reproduction to DNA repair in response to nutritional stress is beneficial as it allows the organisms to survive until conditions improve [21]. Interestingly, a study that manipulated the effect of adult diet on female repair of mutagenized sperm [11] reports results contrasting to those of Agrawal & Wang [18]: the frequency of sex-chromosome losses in mature sperm were higher in well-fed females compared with those starved. These results highlight an additional complication associated with this type of studies, namely that the effects of female or oocyte condition on DNA repair may vary for different types of genetic damage. For example, treating Drosophila females that received X-irradiated sperm with antibiotic actinomycin D resulted in an increase in the frequency of dominant lethals, but a decrease in recessive lethals and translocations resulted with in control females ([12,30] cited in Sankaranaryanan & Sobels [7]).

While previous studies of condition-dependent mutation rate focused largely on the effects of abiotic stresses, resource availability and genetic condition, there are reasons to believe that social factors are likely to be at least as important. Sexual conflict over reproduction is a potential key contributor to changes in individual condition and, therefore, to variation in individual mutation rates. Sexual conflict results from divergent genetic interests of individual males and females in a population [31] and often leads to the evolution of behavioural, morphological or physiological traits in males that are harmful to females [32,33]. The levels of sexual conflict are known to vary between species and populations [34,35], but the effect of the level of sexual conflict on individual mutation rate has never been investigated. Because increased levels of sexual conflict result in a reduction of female condition [36,37], it can also lead to elevated rates of mutation transmission because of reduced investment in DNA repair. Alternatively, this type of environmental stress can result in an increased investment in somatic maintenance, including DNA repair, followed by a reduced mutation rate in females affected by the presence of males.

Drosophila melanogaster has been used as a model organism to study male–female coevolution, and the economics of sexual conflict are well-known for this species [38,39]. The cost of sexual conflict in this system is substantial and has been estimated to reduce female fitness by at least 20 per cent [40]. Therefore, male impact on female phenotypic condition can be high [36,37]. While a large part of this cost is likely to come from male courtship and mounting attempts, as well as from completed matings, it is often difficult to separate the effects of such harassment by males from the costs of reproduction per se. However, it is possible to get around this problem using males lacking viable sperm as well as the bulk of accessory gland proteins (ACPs) [41]. Such males can court, mount and mate with females, but they do not stimulate egg production beyond the level observed in virgin females [41].

In this study, we tested the effect of sexual harassment by males on female condition and mutation rate in D. melanogaster. The number of de novo mutations produced depends on two processes: (i) the damage to the genetic code and (ii) the proportion of damage that is not repaired. Mutation rate can easily be manipulated by exposing females to low levels of gamma radiation, but such an approach confounds germline mutation rate with the somatic mutation rate and, therefore, cannot be used to evaluate the effect of individual condition on mutation transmission [18]. To get around this problem, we focused on the second process, DNA repair, in order to separate between the induced mutation rate and female condition. Following Agrawal & Wang [18], we made use of the fact that the D. melanogaster males cannot repair mutations in their sperm, whereas females can repair sperm DNA prior to fertilization with the help of repair proteins in their eggs. We used spermless and ACP-less males [41] to manipulate female exposure to male harassment, while not inducing a confounding effect owing to costs of reproduction. We manipulated mutation rate by supplying females with either mutagenized or non-mutagenized sperm, and female condition by varying the level of female exposure to male courtship under controlled densities in a 2 × 2 design. This approach allowed us to estimate the effect of male harassment on the yield of dominant lethal mutations in females supplied with mutagenized sperm. Because previous studies reported different results of environmental effects on different types of genetic damage, we conducted additional experiments aimed at estimating the effect of harassment on the yield of sex-linked recessive lethal mutations. We found that male harassment strongly reduces female fitness in terms of net fecundity. However, our results reveal that male harassment does not increase mutation rate in females. Remarkably, females whose overall reproductive performance was greatly reduced by cohabiting with males were better at repairing defected male sperm.

2. Material and methods

(a). Fly stocks

To manipulate the level of male harassment independently of female egg-laying rate, we used males from the DTA-E stock [41] kindly provided by M. Wolfner. These males court females and mate with them but do not transfer sperm or main-cell accessory gland proteins, and do not induce egg laying [41]. Variation in proportion of sperm carrying DNA lesions was manipulated via gamma radiation of males (see below). Males transferring normal or irradiated sperm came from the wild-type laboratory population LHm [38]. In the assay for dominant lethals, females also came from LHm. In the assay for sex-linked recessive mutations, we used females homozygous for the X-chromosome balancer FM1, marked with the dominant eye mutation B (bar eyes). These females had been backcrossed for many generations to the LHm population before the start of the experiments. Flies were reared on a 12 L : 12 D cycle at 25°C. Standard sugar–yeast medium was used in all experiments.

(b). Experimental procedures

(i). Dominant lethals

We independently manipulated female exposure to male harassment and the proportion of mutated male sperm transferred to females in a 2 × 2 design. One-day-old virgin females (LHm) were either housed in 36 ml (22 mm wide and 95 mm high) vials without males in groups of 44 (30 vials: no harassment treatment), or in groups of 11 together with 33 DTA-E males (120 vials: harassment treatment), for 12 days. Flies were flipped into fresh vials every fourth day. On day 13, females from each of the low-harassment vials were transferred under light CO2 anaesthesia to a fresh vial. Similarly, females from four high-harassment level vials were combined into a fresh vial. The 30 vials with females from each of the two sexual harassment level treatments were subsequently divided into two sets of 15 vials. Females from one set of vials were mated with irradiated males and females from the other set of vials to normal males, as follows. For each vial, 80 7-day-old wild-type males (LHm) were added for a period of 3 h. Previous experiments have shown that virtually all virgin females mate once and only once under similar conditions [42–44]. The males had either been gamma-irradiated to induce lesions in the sperm DNA or had been left untouched. Irradiated males had been exposed to 28 Gy. This level of radiation was chosen because previous studies [7], as well as a pilot study in our laboratory (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S1), showed that about 60 per cent of all eggs fail to hatch owing to problems associated with irradiated sperm, when mated with males exposed to this level of radiation.

In the morning of day 14, females were flipped into egg-laying chambers. These chambers contained small Petri dishes, filled with standard food medium topped with ad libitum yeast paste. After 4.5 h, the females were cleared, and the total number of eggs per Petri dish was counted. This number was taken as a proxy for female condition. Twenty-eight hours after the flies were removed from the egg-laying chambers; the dishes with eggs were stored at 4°C, to stop further embryonic/larval development. The proportion of unhatched eggs was subsequently scored. The same procedure was repeated twice.

(ii). Sex-linked recessive lethals

In order to measure the effect of sexual harassment on the rate of transmission of sex-linked lethals, we used a modified protocol of the Basc method [45]. In two independent experiments, females homozygous for FM1 were either kept in vials of 44 females (14 vials) or in groups of 11 with 33 DTA-E males (55 vials), for 6 days in experiment 1 and 9 days in experiment 2. These females were subsequently divided into groups of two and housed with two 7-day-old-irradiated LHm males overnight. Males were irradiated with 45 Gy in experiment 1 and with 50 Gy in experiment 2. In the morning, males and females were discarded, and the number of eggs laid in the mating vials was scored for 100 vials in each treatment group (in experiment 2, we scored 98 vials from the harassed females and 107 vials for non-harassed females) and taken as measure of female condition. Nine days later, virgin females (on average 2.23±0.07 s.e., daughters per two mothers), heterozygous for the FM1 and the paternally derived irradiated X chromosome were collected. These females were subsequently mated with non-irradiated LHm males, and the number of FM1/Y and Xirradiated/Y sons from these crosses was scored to estimate the proportion of sex-linked lethals in different treatment groups.

(c). Statistical analyses

We used ANOVA to test for the effect of sexual harassment on female condition in the assay for dominant lethals. We used eggs laid per female as the dependent variable, which was log-transformed prior to the analyses. To simultaneously test whether male irradiation status had an effect on female fecundity, we used a full factorial two-way fixed effects ANOVA with sexual harassment level and male irradiation status as fixed factors.

The proportion of eggs that fail to hatch after females mated with males with irradiated sperm, I, depends both on the proportion of eggs that normally fail to hatch, N, and the proportion of eggs that fail to hatch owing to the effect of irradiation r. The relationship between I, N and r can be expressed in the following way: I = N + (1 − N) × r. In our experiments, we measured I and N in 15 replicates for each treatment group. To test for the effect of elevated exposure to sexual harassment on female capacity to repair irradiated sperm, we used our estimated values of I and N to calculate r for each replicate. These values were compared between treatment groups in two different ways. Because there was no connection between replicates in which females were exposed to irradiated and normal males, we calculated the mean N-value per treatment group across the 15 replicates that had been exposed to normal males, and used these values to calculate 15 r-values per treatment group (these 15 r-values were used to calculate s.e.). We then used t-test to test for a difference between treatments. Furthermore, we also bootstrapped the data, by randomly sampling with replacement, of 15 N replicates and 15 I replicates that we randomly paired up separately for each treatment group. From these pairs, we calculated 15 r-values. We then calculated the difference between the sum of the r-values of females that had been exposed to sexual harassment and those that had not. This procedure was repeated 100 000 times to calculate a 95% CI for the difference in r between treatment groups. We note that the results are the same if the data are analysed in a two-way full factorial ANOVA with sexual harassment level and male irradiation status as factors, but the approach described above is more accurate.

To evaluate the effect of sexual harassment on female ability to repair X-linked recessive mutations, we applied a modified version of the analyses used by Agrawal & Wang [18]. Provided that the X-chromosome transmitted from the irradiated grandfather did not express a recessive mutation, the proportion of the two genotypes of grandsons (FM1/Y and Xirradiated/Y) should be the same (assuming no intrinsic viability difference between the genotypes). However, whenever the Xirradiated chromosome carries a recessive lethal, or a nearly mutation, the proportion of Xirradiated/Y sons to FM1/Y sons should be very low. For each set of grandsons originating from a single mother, we calculated r = L1/20/L1/2, where L1/2 is the likelihood that the observed proportion of Xirradiated/Y sons is drawn from a binominal distribution where both genotypes occur at 50 per cent, and L1/20 is the corresponding likelihood that the observed proportion is drawn from a population where Xirradiated/Y sons occur at 5 per cent. The ratio of these likelihoods thus indicates the likelihood that the observed proportion of Xirradiated/Y sons came from a population where the occurrence of these sons was found to be 5 per cent compared with 50 per cent. We classified all broods with an r ≥ 10 as broods with a lethal, or near to lethal recessive X-linked mutation, and broods with an r ≤ 0.1 as broods not containing a nearly lethal recessive X-linked mutation. Broods falling in between these r-values were classified as unknown with respect to whether the Xirradiated chromosome carried a recessive lethal or not and were excluded from any further analyses. We then used a two-proportion z-test to evaluate whether the proportion of X-linked recessive lethals differed between grandsons of females exposed to different level of sexual harassment.

3. Results

(a). Dominant lethals

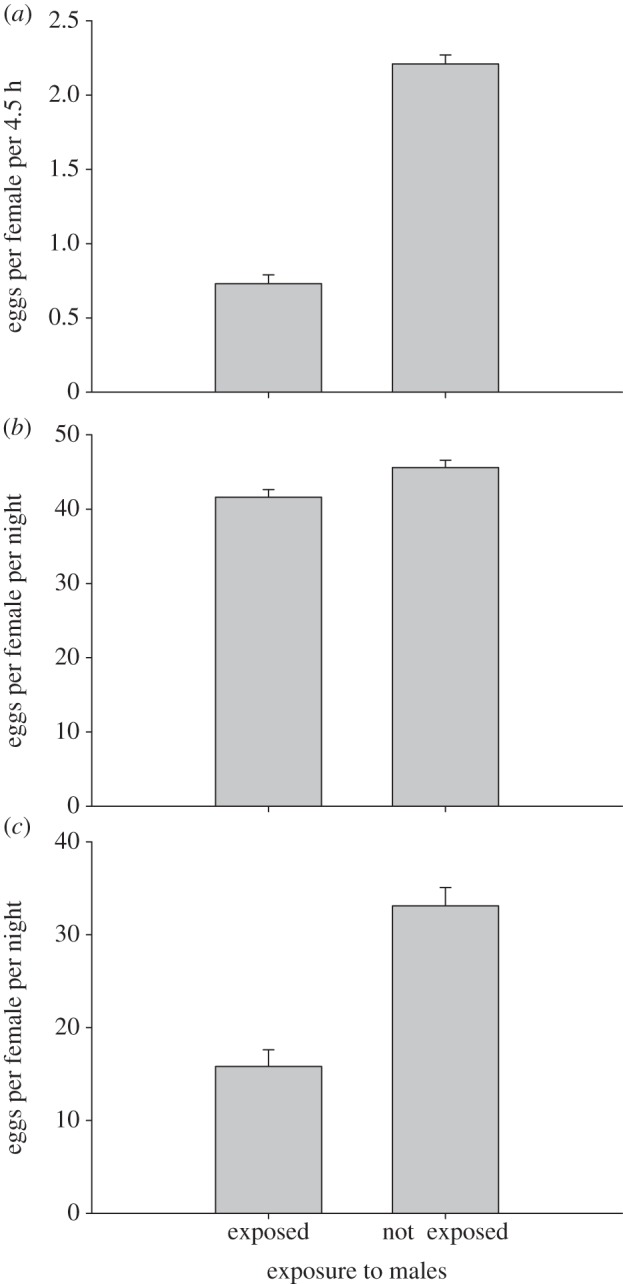

Females that had been exposed to males laid significantly fewer eggs compared with females that were housed together with other females (mean ± s.e., not exposed to males: 2.21±0.06; exposed to males: 0.73±0.06), while mating to irradiated males had a small but significant negative effect on female fecundity (mean±s.e. mated with normal males: 1.58±0.06; mated with irradiated males: 1.35±0.06; ANOVA (fecundity, irradiation, interaction); F1,59 = 320.94, 4.60, −0.22; p < 0.0001, p = 0.036, p = 0.639; figure 1a).

Figure 1.

The effect of exposure to males on female fecundity (mean±s.e.) over three different experiments ((a) experiment on dominant lethals; (b) first experiment on recessive lethal and (c) second experiment on recessive lethals) presented in the chronological order. See text for the details of exposure in different experiments.

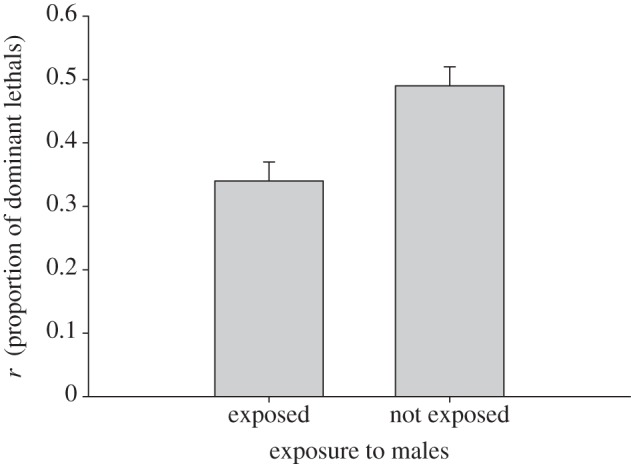

Offspring of females exposed to sexual harassment suffered less from dominant lethals compared with offspring of females that had not been exposed (mean r±s.e. exposed to males: 0.34±0.03; not exposed to males: 0.49±0.03; t = 3.27, d.f. = 27, p = 0.0029; figure 2). The bootstrap 95% CI for the difference between treatment groups confirmed this result (rexposed to males − rnot exposed to males: −4.37−−0.17).

Figure 2.

The effect of exposure to males on r (mean±s.e.), the proportion of dominant lethals in female progeny owing to irradiation of male sperm. See text for the details on the calculation of r.

(b). Sex-linked recessive lethals

In these experiments, females also laid fewer eggs after exposure to males (mean±s.e., experiment 1 and experiment 2: exposed to males: 41.6±1.02, 15.8±1.79; not exposed to males: 45.6±0.98, 33.1±1.97; t = 2.84, 6.43; d.f. = 198, 203; p = 0.005, p < 0.0001; figure 1b,c).

In experiment 1, we scored 40 683 male offspring of 872 females. Thirty-two out of 341 classifiable females whose mothers had been exposed to sexual harassment likely carried an X-linked recessive lethal. For females whose mothers had not been exposed to sexual harassment these numbers were 45 out of 422. There was no difference in the frequency of X-linked lethal mutations between treatment groups (z = 0.59; p = 0.55). In experiment 2, we scored 26 462 male offspring of 858 females. The corresponding numbers of classifiable females were 33 carrying an X-linked recessive lethal out of 271 exposed to sexual harassment and 66 out of 429 not exposed to sexual harassment. There was again no difference in the proportion of X-linked recessive lethals among treatment groups (z = 1.21; p = 0.23). In both experiments, if anything, there was a tendency towards recessive lethals being transmitted at a higher rate through high-condition females, but the combined p-value of these assays was not significant (Fisher's combined probability test, χ2 = 4.14, d.f. = 4, p = 0.39).

4. Discussion

Females consistently suffered from cohabitation with males across three different experiments with reductions in fecundity ranging from 8.77 to 66.97 per cent, depending on the amount and the context of exposure to male harassment. On the other hand, females that were exposed to males were better able to cope with mutagenized sperm and had relatively lower levels of dominant lethal mutations in their offspring, while there was no measurable effect on the recessive lethals. The costs of sexual conflict in fruitflies are well-documented, and our study is in line with previous results with respect to fecundity [36,37,43]. However, the effect of male harassment on DNA repair in females suggests that social effects are likely to mediate condition-dependent mutation rate and this may have important evolutionary implications.

Our finding that females cohabiting with males were better able to repair damage to male sperm corroborates the hypothesis that environmental stress results in increased investment in somatic maintenance, including investment in DNA repair [21,46,47]. A model by Shanley & Kirkwood [21] explicitly predicts that animals should respond to food shortage, which corresponds to the classic prolongevity effect of DR on lifespan [23,26], by increasing investment in DNA repair even at the cost of temporary reduction or complete cessation of reproduction. There is a large body of literature that provides both indirect and direct empirical support for the role of stress in upregulation of repair mechanisms ([48] reviewed in [49]). For example, repair of DNA damage measured as unscheduled DNA synthesis was higher in the cells of mice and rats kept under DR compared with cells from ad libitum fed animals [49]. Similarly, pre-treatment with heat shock resulted in improved DNA repair in yeast [50]. More generally, sirtuin protein (SIRT6) has recently been shown to stimulate DNA repair in cells under increased oxidative stress [51]. This multifunctional protein is a member of sirtuin family of proteins that play a key role in regulating metabolism, lifespan (but see Burnett et al. [52]), chromosomal stability and stress response across taxa [53,54]. This recent finding directly integrates stress signalling and DNA repair pathways by showing that repair increases 16-fold under stress [51].

Our results differ from Agrawal & Wang [18] who manipulated larval nutrition, but are similar to Clark [11] who manipulated adult nutrition in fruitflies. Agrawal & Wang [18] found increase in recessive lethals in flies that were undernourished during their development, whereas we found decrease in dominant lethals and no effect in recessive lethals in flies that were in poor condition after their exposure to males. While Agrawal & Wang's [18] study had more power to detect the effect in recessive lethals, it is worth noting that, in our study, the direction of the effect was opposite in both experiments on recessive lethals and in line with our finding regarding dominant lethals—i.e. reduced mutation rate in poor condition flies. This directionality formally allows us to use Fisher's combined probabilities approach across all three experiments and the result suggests that flies exposed to males had overall higher mutation rate (χ2 = 15.82, d.f. = 6, p = 0.015). However, we do not believe that it is useful to estimate the overall mutation rate in the case of this study and for this reason we present this test in §4 rather than in §3. Earlier studies indicated that the effect of maternal physiological condition on mutation rate can vary depending on the specific environmental effect involved and the type of damage that was assessed in the experiment [7,10–12]. For example, treating fruitflies with an antibiotic actinomycin D led to an increase in dominant lethals but to a decrease in recessive lethals and translocations [12,30]. Interestingly, this latter finding was interpreted as decrease in efficiency of repair, leading to increase in dominant lethals and a decrease in translocations and recessive lethals, which could arise as a result of misrepair [7]. While we find this suggestion highly speculative in the absence of concrete evidence, it is possible to interpret the results of Agrawal & Wang [18] as an indication of reduction in repair efficiency. However, in our study, we definitely did not find any reduction in recessive lethals, and we suggest that taken together the results of all studies point to the possibility that repair is upregulated when animals are stressed ([11] and this study) but may proceed less efficiently when animals are severely affected by the lack of resources [18] or by genotoxic stress [19].

Male–female coevolution is a dynamic process and the intensity of sexual conflict, as well as the absolute cost of intersexual interactions for both sexes, is likely to differ across populations at different points in evolutionary time [43,55,56]. For example, the cost of mating for females can be higher in populations where male secondary sexual traits that increase male mating success at the cost to females are one step ahead of female defences in the evolutionary arms race [57]. Our results suggest that in populations where females experience higher absolute cost of mating or male harassment, both female fecundity and population mutation rate will be reduced. Reduction in mutation rate can be beneficial for population viability but can also have negative effects during adaptation to a novel or changing environment. For example, the rate of adaptation in populations of fruitflies increased when mutation rate was increased by X-irradiation [58]. While theory predicts that sexual selection is likely to accelerate the rate of adaptation to a novel environment [59–62], recent experimental studies struggled to support this prediction [63–65] (but see Long et al. [66]). Sexual conflict has been repeatedly invoked as a potential explanation for the lack of positive effects of sexual selection on the rate of adaptation [63–65,67]. This study provides yet another potential reason for why sexual selection often fails to promote adaptation—the mutation rate in the population can be higher when sexual selection and sexual conflict are removed or reduced.

To summarize, we showed that male harassment reduces fecundity but increases the repair of mutagenized sperm in female fruitflies. This result is in line with the hypothesis that exposure to stress increases investment in DNA repair. We found a strong effect of exposure to males on dominant lethals but no measurable effect on recessive lethals, which is in line with previous reports suggesting that effects of maternal environment on repair can differ depending on both the type of stress suffered and the type of damage incurred [7]. While several studies indicated that mutation rate can depend on genotoxic stress [19] and resource availability [11,18], the role of social effects remained largely unexplored. These results put forward social effects as potential major contributors to condition-dependent mutation rate. Given the prevalence of social effects such as density or courtship on individual condition, the extent of these effects on mutation rate in different organisms, as well as their long-term evolutionary implications, require further investigation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Alex Hayward and Felix Zajitschek for help in the laboratory, to Mariana Wolfner for sharing DTA-E flies, and to Aneil Agrawal, Russell Bonduriansky and Rebecca Dean for fruitful discussions of the preliminary results. The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council grants to A.A.M., S.I., H.L. and U.F.; European Research Council Starting Grant 2010 to A.A.M and the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, Nilsson-Ehle Donationerna and Erik Philip Sörensens Stiftelse to U.F.

References

- 1.Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D. 1998. Some evolutionary consequences of deleterious mutations. Genetica 103, 3–19 10.1023/A:1017066304739 (doi:10.1023/A:1017066304739) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kondrashov AS. 1993. Classification of hypotheses on the advantage of amphimixis. J. Hered. 84, 372–387 10.1002/9780470015902.a0001716 (doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0001716) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keightley PD, Eyre-Walker A. 2000. Deleterious mutations and the evolution of sex. Science 290, 331–333 10.1126/science.290.5490.331 (doi:10.1126/science.290.5490.331) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondrashov AS. 1988. Deleterious mutations and the evolution of sexual reproduction. Nature 336, 435–440 10.1038/336435a0 (doi:10.1038/336435a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drake JW, Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D, Crow JF. 1998. Rates of spontaneous mutation. Genetics 148, 1667–1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidenreich E. 2007. Adaptive mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42, 285–311 10.1080/10409230701507773 (doi:10.1080/10409230701507773) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sankaranaryanan K, Sobels FH. 1976. Radiation genetics. In The genetics and biology of Drosophila, vol. 1C (pp. 1089–1250) (eds Ashburner M, Novitski E.). New York, NY: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novitsky E. 1961. Post treatment of irradiated sperm by low temperature. Drosophila Inf. Serv. 35, 92 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kauffman BP. 1964. Modification of the frequency of chromosomal rearrangements induced by X-rays in Drosophila. III. Effect of supplementary treatment at the time of chromosome recombination. Genetics 31, 449–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herskowitz IH. 1963. An influence of maternal condition upon the gross chromosomal mutation frequency recovered from X-rayed sperm of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 48, 703–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark AM. 1972. Influence of nutritional state of females on frequency of X/O malesrecovered after matings with irradiated males. Drosophila Inf. Serv. 49, 75 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proust JP, Sankaranaryanan K, Sobels FH. 1972. The effects of treating Drosophila females with Actinomycin-D on the yields dominant lethals, translocations and reccessive lethals from X-irradiated spermatozoa. Mutat. Res. 16, 65–76 10.1016/0027-5107(72)90065-6 (doi:10.1016/0027-5107(72)90065-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wurgler FE, Maier P. 1972. Genetic control of mutation induction in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Sex-chromosome loss in X-rayed mature sperm. Mutat. Res. 15, 41–53 10.1016/0027-5107(72)90090-5 (doi:10.1016/0027-5107(72)90090-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall BG. 1992. Selection-induced mutations occur in yeast. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 4300–4303 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4300 (doi:10.1073/pnas.89.10.4300) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goho S, Bell G. 2000. Mild environmental stress elicits mutations affecting fitness in Chlamydomonas. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 267, 123–129 10.1098/rspb.2000.0976 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.0976) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avila V, Chavarrias D, Sanchez E, Manrique A, Lopez-Fanjul C, Garcia-Dorado A. 2006. Increase of the spontaneous mutation rate in a long-term experiment with Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 173, 267–277 10.1534/genetics.106.056200 (doi:10.1534/genetics.106.056200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baer CF. 2008. Does mutation rate depend on itself? PLoS Biol. 6, 233–235 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060233 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060233) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal AF, Wang AD. 2008. Increased transmission of mutations by low-condition females: evidence for condition-dependent DNA repair. PLoS Biol. 6, 389–395 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060030 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharp NP, Agrawal AF. 2012. Evidence for elevated mutation rates in low-quality genotypes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6142–6146 10.1073/pnas.1118918109 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1118918109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotton S. 2009. Condition-dependent mutation rates and sexual selection. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 899–906 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01683.x (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01683.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shanley DP, Kirkwood TBL. 2000. Calorie restriction and aging: a life-history analysis. Evolution 54, 740–750 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00076.x (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00076.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirkwood TBL, Austad SN. 2000. Why do we age? Nature 408, 233–238 10.1038/35041682 (doi:10.1038/35041682) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piper MDW, Partridge L. 2007. Dietary restriction in Drosophila: delayed aging or experimental artefact? PLoS Genet. 3, 0461–0466 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030057 (doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030057) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weindruch R, Walford RL. 1988. The retardation of aging and disease by dietary restriction. Springfield, IL: Thomas [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maklakov AA, Simpson SJ, Zajitschek F, Hall MD, Dessmann J, Clissold F, Raubenheimer D, Bonduriansky R, Brooks RC. 2008. Sex-specific fitness effects of nutrient intake on reproduction and lifespan. Curr. Biol. 18, 1062–1066 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.059 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.059) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. 2010. Extending healthy life span-from yeast to humans. Science 328, 321–326 10.1126/science.1172539 (doi:10.1126/science.1172539) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zajitschek F, Zajitschek SRK, Friberg U, Maklakov AA. 2012. Interactive effects of sex, social environment, dietary restriction, and methionine on survival and reproduction in fruit flies. AGE. (doi:10.1007/s11357-012-9445-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia AM, et al. 2008. Effect of Ames dwarfism and caloric restriction on spontaneous DNA mutation frequency in different mouse tissues. Mech. Ageing Dev. 129, 528–533 10.1016/j.mad.2008.04.013 (doi:10.1016/j.mad.2008.04.013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edman U, Garcia AM, Busuttil RA, Sorensen D, Lundell M, Kapahi P, Vijg J. 2009. Lifespan extension by dietary restriction is not linked to protection against somatic DNA damage in Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell 8, 331–338 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00480.x (doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00480.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Proust JP. 1969. Action d'un pre-traitment des femmeles de Drosophila melanogaster avec de l'Actinomycin D sur la frequence des letaux dominants induits par les rayons X dans les spermatozoides murs. Compt. Rend. Acad. Sci. 269, 86–88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker GA. 1979. Sexual selection and sexual conflict. In Sexual selection and reproductive competition in insects (eds Blum MS, Blum NA.), pp. 123–166 New York, NY: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arnqvist G, Rowe L. 2005. Sexual conflict. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonduriansky R, Chenoweth SF. 2009. Intralocus sexual conflict. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 280–288 10.1016/j.tree.2008.12.005 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.12.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chapman T, Arnqvist G, Bangham J, Rowe L. 2003. Sexual conflict. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 41–47 10.1016/S0169-5347(02)00004-6 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)00004-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pizzari T, Snook RR. 2003. Perspective: sexual conflict and sexual selection: chasing away paradigm shifts. Evolution 57, 1223–1236 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00331.x (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00331.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friberg U, Arnqvist G. 2003. Fitness effects of female mate choice: preferred males are detrimental for Drosophila melanogaster females. J. Evol. Biol. 16, 797–811 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00597.x (doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00597.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pitnick S, Garcia-Gonzalez F. 2002. Harm to females increases with male body size in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 1821–1828 10.1098/rspb.2002.2090 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2090) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rice WR, Linder JE, Friberg U, Lew TA, Morrow EH, Stewart AD. 2005. Inter-locus antagonistic coevolution as an engine of speciation: assessment with hemiclonal analysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 6527–6534 10.1073/pnas.0501889102 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0501889102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fricke C, Perry J, Chapman T, Rowe L. 2009. The conditional economics of sexual conflict. Biol. Lett. 5, 671–674 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0433 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0433) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart AD, Morrow EH, Rice WR. 2005. Assessing putative interlocus sexual conflict in Drosophila melanogaster using experimental evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 2029–2035 10.1098/rspb.2005.3182 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3182) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalb JM, Dibenedetto AJ, Wolfner MF. 1993. Probing the function of Drosophila melanogaster accessory grands by directed cell ablation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 8093–8097 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8093 (doi:10.1073/pnas.90.17.8093) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holland B, Rice WR. 1999. Experimental removal of sexual selection reverses intersexual antagonistic coevolution and removes a reproductive load. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5083–5088 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5083 (doi:10.1073/pnas.96.9.5083) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rice WR. 1996. Sexually antagonistic male adaptation triggered by experimental arrest of female evolution. Nature 381, 232–234 10.1038/381232a0 (doi:10.1038/381232a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friberg U, Dowling DK. 2008. No evidence of mitochondrial genetic variation for sperm competition within a population of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Evol. Biol. 21, 1798–1807 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01581.x (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01581.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spencer WP, Stern C. 1948. Experiments to test the validity of the linear R-dose mutation frequency relation in Drosophila at low dosage. Genetics 33, 43–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirkwood TBL. 2005. Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell 120, 437–447 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.027 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirkwood TBL, Shanley DP. 2005. Food restriction, evolution and ageing. Mech. Ageing Dev. 126, 1011–1016 10.1016/j.mad.2005.03.021 (doi:10.1016/j.mad.2005.03.021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rattan SIS. 2008. Hormesis in aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 7, 63–78 10.1016/j.arr.2007.03.002 (doi:10.1016/j.arr.2007.03.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haley-Zitlin V, Richardson A. 1993. Effect of dietary restriction on DNA repair and DNA damage. Mutat. Res. 295, 237–245 10.1016/0921-8734(93)90023-V (doi:10.1016/0921-8734(93)90023-V) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keszenman DJ, Candreva EC, Nunes E. 2000. Cellular and molecular effects of bleomycin are modulated by heat shock in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. DNA Repair 459, 29–41 10.1016/S0921-8777(99)00056-7 (doi:10.1016/S0921-8777(99)00056-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mao ZY, Hine C, Tian X, Van Meter M, Au M, Vaidya A, Seluanov A, Gorbunova V. 2011. SIRT6 promotes dna repair under stress by activating PARP1. Science 332, 1443–1446 10.1126/science.1202723 (doi:10.1126/science.1202723) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burnett C, et al. 2011. Absence of effects of Sir2 overexpression on lifespan in C. elegans and Drosophila. Nature 477, 482–485 10.1038/nature10296 (doi:10.1038/nature10296) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kanfi Y, Naiman S, Amir G, Peshti V, Zinman G, Nahum L, Bar-Joseph Z, Cohen HY. 2012. The sirtuin SIRT6 regulates lifespan in male mice. Nature 483, 218–221 10.1038/nature10815 (doi:10.1038/nature10815) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Auwerx J. 2012. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 225–238 10.1038/nrn3209 (doi:10.1038/nrn3209) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rönn J, Katvala M, Arnqvist G. 2007. Coevolution between harmful male genitalia and female resistance in seed beetles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 10 921–10 925 10.1073/pnas.0701170104 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0701170104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arnqvist G, Rowe L. 2002. Correlated evolution of male and female morphologies in water striders. Evolution 56, 936–947 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01406.x (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01406.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hotzy C, Arnqvist G. 2009. Sperm competition favours harmful males in seed beetles. Curr. Biol. 19, 404–407 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.045 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.045) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ayala FJ. 1969. Evolution of fitness V. Rate of evolution of irradiated populations of Drosophila. Genetics 63, 790–793 10.1073/pnas.63.3.790 (doi:10.1073/pnas.63.3.790) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lorch PD, Proulx S, Rowe L, Day T. 2003. Condition-dependent sexual selection can accelerate adaptation. Evol. Ecol. Res. 5, 867–881 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Agrawal AF. 2001. Sexual selection and the maintenance of sexual reproduction. Nature 411, 692–695 10.1038/35079590 (doi:10.1038/35079590) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Whitlock MC. 2000. Fixation of new alleles and the extinction of small populations: drift load, beneficial alleles, and sexual selection. Evolution 54, 1855–1861 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb01232.x (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb01232.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Siller S. 2001. Sexual selection and the maintenance of sex. Nature 411, 689–692 10.1038/35079578 (doi:10.1038/35079578) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holland B. 2002. Sexual selection fails to promote adaptation to a new environment. Evolution 56, 721–730 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01383.x (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01383.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maklakov AA, Bonduriansky R, Brooks RC. 2009. Sex differences, sexual selection, and ageing: an experimental evolution approach. Evolution 63, 2491–2503 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00750.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00750.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rundle HD, Chenoweth SF, Blows MW. 2006. The roles of natural and sexual selection during adaptation to a novel environment. Evolution 60, 2218–2225 (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01859.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Long TAF, Agrawal AF, Rowe L. 2012. The effect of sexual selection on offspring fitness depends on the nature of genetic variation. Curr. Biol. 22, 204–208 10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.020 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Whitlock M, Agrawal AF. 2009. Purging the genome with sexual selection: reducing mutation load through selection on males. Evolution 63, 569–582 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00558.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00558.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]