Abstract

Background:

As a pilot project, Indian Psychiatric Society conducted the first multicentric study involving diverse settings from teaching institutions in public and private sectors and even privately run psychiatric clinics.

Aim of the Study:

To study the typology of functional somatic complaints (FSC) in patients with first episode depression.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 741 patients from 16 centers across the country participated in the study. They were assessed on Bradford Somatic Symptom inventory for FSC, Beck Depression Inventory for severity of depression, and Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale- anxiety index (CPRS-AI) for anxiety symptoms.

Results:

The mean age of the study sample was 38.23 years (SD-11.52). There was equal gender distribution (male - 49.8% vs. females 50.2%). Majority of the patients were married (74.5%), Hindus (57%), and from nuclear family (68.2%). A little over half of the patients were from urban background (52.9%). The mean duration of illness at the time of assessment was 25.55 months. Most of the patients (77%) had more than 10 FSCs, with 39.7% having more than 20 FSCs as assessed on Bradford Somatic Inventory. The more common FSC as assessed on Bradford Somatic Inventory were lack of energy (weakness) much of the time (76.2%), severe headache (74%) and feeling tired when not working (71%), pain in legs (64%), aware of palpitations (59.5%), head feeling heavy (59.4%), aches and pains all over the body (55.5%), mouth or throat getting dry (55.2%), pain or tension in neck and shoulder (54%), head feeling hot or burning (54%), and darkness or mist in front of the eyes (49.1%). The prevalence and typology of FSCs is to a certain extent influenced by the sociodemographic variables and severity of depression.

Conclusion:

Functional somatic symptoms are highly prevalent in Indian depressed patients and hence deserve more attention while diagnosing depression in Indian setting.

Keywords: Depression, Functional somatic complaints, India

INTRODUCTION

Studies from the various parts of the world suggest that many patients suffering from depression manifest physical complaints which are not specifically identified by the nosological systems. It is suggested that many a times, these functional somatic complaints (FSC) dominate the clinical picture to such an extent that they exert a crucial influence on the perception of the illness. Due to the predominance of physical symptoms, many patients believe their depressive illness to be physical in origin, and consult a physician rather than mental health professionals and this may lead to misutilization of medical services.[1] FSCs are known to increase the burden and disability associated with depression. Increased burden of FSCs in patients with depression also leads to increased utilization of healthcare services, greater economic burden[2–4] and contributes greatly to the recurrence of another new depressive episode several years later.[5–10]

Studies done in patients with depression presenting to different treatment settings like primary care, medical outpatient, and psychiatric outpatient clinics suggest high prevalence of FSCs across various treatment setting. Studies done in primary care setting suggest that about 66 to 73% of patients with depression and anxiety have FSC.[11–13] The prevalence figures of FSC in clinic-based studies have varied between 66 and 92%.[14–19]

Studies from different parts of the world have also described the typology of FSC in depression and in general suggest that painful symptoms are highly prevalent, although many studies have also described painless FSCs.[20–24]

Very few studies from India have focused on FSC in patients with depression,[25–26] although there are few studies which have focused on the prevalence of non-organic FSC in outpatients in general.[27–30] The only study which focused on FSC in depression reported a prevalence rate of FSC in patients with depression reported the prevalence of same to be 100%.[26] The study evaluated the type of FSC by using PHQ-15 and reported feeling tired or having low energy (92.7%) as the most common symptom, followed by troubled sleeping (79.9%), nausea, gas and indigestion (68.2%), headache (68.2%), pain in arms, legs, or joints (65.9%), and feeling that heart is racing (65.2%) as other common symptoms.[26] Another study evaluated the type of FSC using Bradford Somatic Inventory reported lack of energy much of the time (98%) as the most common symptom, followed by feeling tired when not working (82%), head feeling heavy (74%), feeling of constriction of head, as if being gripped (68%), aches and pains all over the body (64%) as the other common symptoms.[25] Studies which have focused on patients with FSCs, most of whom have been diagnosed as having depression and seeking a psychiatric consultation, have shown that headache is the commonest FSC, reported by 81 to 84% of cases.[27,28,30] Other commonly reported symptoms include aches and pains,[27,28,30,31] disturbance in biological functions (83%),[29] weakness of body and mind (72%),[29] tiredness (84%), palpitation (44-75%), sleeplessness (66-72%), weakness (66%), pain in the whole body except head and chest (63%), pain in chest (51-63%), poor appetite (63%), neck pain (60%), giddiness/fainting spells (57%), numbness/tingling sensation (57%), dizziness (49%), tremulousness of hands (46%), abdominal fullness/heaviness (43%), nausea (39%), cold sensation in the body (30%), burning sensation in whole body except for head and chest (30%).[27–31]

As evident from the literature review, although there are sporadic studies from a few centers in India, yet there is no study which has assessed the prevalence of FSC across various regions of the country using the common methodology. Hence, as a pilot project of Indian Psychiatric Society, this multicentric study aimed to estimate the prevalence and typology of FSCs in patients with first episode unipolar depression. Another aim of the project was to test the feasibility of conducting funded multicentric studies and provide research opportunities to its membership.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a multicentric study, funded by the Indian Psychiatric Society. A cross sectional design was employed. The patients were assessed only once at the time of intake into the study. All the patients were recruited after obtaining a proper written informed consent and the study was approved by the ethics committees of the institutes or local ethics committees where the study was conducted.

Sixteen centers across the country participated in the study, of which 4 centers each were in the south zone and east zone, 3 centers each in the north and west zone, and 2 centers in the central zone of Indian Psychiatric Society. From the east zone, the participating centers were at Kolkata, Patna, Tezpur, and Guwahati) and from north zone the participating centers were at Chandigarh, New Delhi, and Ludhiana. The four centers in the south zone were located at Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, and Manipal and the centers in the central zone were at Agra and Lucknow. Centers in the west zone were located at Ahmadabad, Mumbai, and Wardha. Of the various centers, 4 centers were in the centrally funded Institutes with 2 having general hospital psychiatric units (Chandigarh, New Delhi) and 2 were in mental hospital set up (Bengaluru and Tezpur). Six centers were in the state Government run Medical Colleges (Ahmadabad, Kolkata, Lucknow, Mumbai, Patna, Guwahati), 3 centers were in privately run medical colleges (Chennai, Manipal, Wardha), 2 in privately run clinics (Hyderabad and Ludhiana), and 1 center was in state funded Mental Hospital (Agra).

To be included in the study, the patients were required to fulfill the criteria for Major Depressive Disorder as per DSM-IV,[32] age between 16 to 65 years, duration of depression of at least 1 month, and presence of at least one FSC as per Bradford Somatic Inventory.[33] Patients with diagnosis of severe depression with psychotic symptoms, recurrent depressive disorder, other comorbid psychiatric illness(s), substance use disorders including heavy smoking, organic brain syndromes, and chronic debilitating physical illnesses like diabetes, hypertension, and end-stage organ failure were excluded. Patients having a physical illness which could explain the reported somatic complaints were also excluded.

The following instruments were used for the purposes of this study:

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI):[34,35] The MINI is a brief structured interview for diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in DSM-IV and ICD-10, e.g., major depressive episode, dysthymia, psychoactive substance use disorders, etc., It is used by clinicians and can be administered over a short period of time (mean, 18.7 minutes; median, 15 minutes). The MINI is divided into modules corresponding to diagnostic categories. It elicits all the symptoms listed in the symptom criteria for DSM-IV and ICD-10 for 15 major Axis I diagnostic categories, one Axis II disorder and for suicidality. Questions are rated as either present or absent. Studies comparing the MINI with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R: Patient version (SCID) and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview for ICD-10 (CIDI) have shown it to be an instrument with high validity and reliability.

Bradford Somatic Inventory (BSI):[33] The Bradford Somatic Inventory is a multi-ethnic inventory of FSCs associated with anxiety and depression. It has 46 items which enquires about the FSCs during the previous month and, if the subject has experienced a particular symptom, whether the symptom has occurred on more or fewer than 15 days during the month (scoring 2 or 1, respectively). Test–retest reliability of the BSI administered after an interval of a week has been found to be good, with overall reliability coefficient of 0.86 and a median value of 0.63 in a British primary care population. Based on the total score, FSCs are categorized into 3 grades (a score >40 is considered to be the ‘high’ range, 26-40 ‘middle’ range, and 0-25 ‘low’ range).

Beck's Depression Inventory:[36] It was used to assess the severity of depression. It has 21 items, which describe a specific behavioral manifestation of depression which is rated on a graded series of 4-5 evaluation statements. BDI has been shown to have good internal consistency, test-retest and split half reliability.

Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale-Anxiety Index (CPRS-AI):[37] This was used to assess the level of anxiety. It comprises of 7 items, each rated on a 4 point scale of varying from 0 to 3.

Procedure

Patients with a clinical diagnosis of depression and meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were approached for participation in the study. They were explained about the nature of the study and patients who agreed to participate and provided informed consent were recruited. The MINI was administered to confirm the diagnosis of major depressive disorder and to rule out other psychiatric disorders. Patients who fulfilled the criteria for major depressive disorder were assessed on Bradford Somatic Inventory. Thereafter, these patients were assessed on Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI) and Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale-Anxiety Index (CPRS-AI).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis in terms of mean and standard deviation with range for continuous variables and frequency with percentage for ordinal and nominal variables was computed. Correlations between the variables were assessed using Pearson's product moment and Spearman's rank order correlation. Comparisons were done using the Chi-square test, t-test and Fischer exact test.

RESULTS

Across the 16 centers, 746 patients were recruited for the study. However, 5 patients were excluded due to age of the participants being more than 65 years (n=4) and incomplete data (n=1). Of the 741 patients, 215 patients were from East zone, 147 were from North zone, 143 from South zone, 120 from Central zone, and 116 from West zone.

Sociodemographic profile

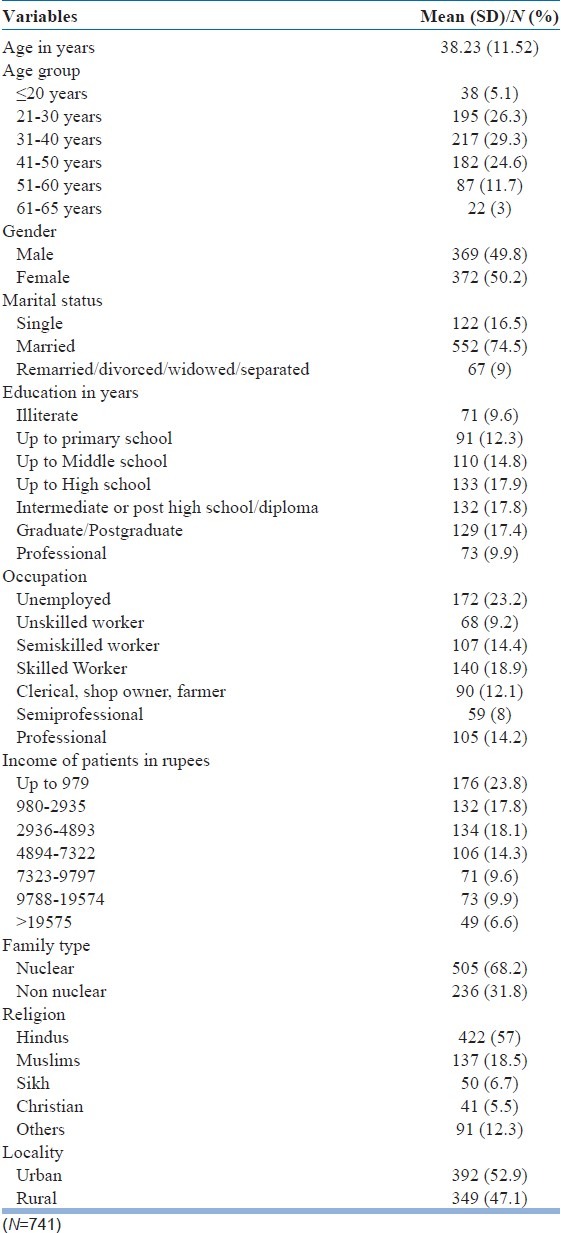

The sociodemographic profile of the study participants is shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 38.23 years (range, 16-65), with about 80% of patients in the age group of 21 to 50 years. There was nearly equal gender distribution. Majority of the participants were married, educated up to or beyond high school level, were employed, were earning less than rupees 7322, and belonged to nuclear families. Majority of the participants were Hindus and about one-fifth of them were either Muslims and about one-fifth were from other religious affiliations. There was nearly equal representation of participants from urban and rural locality.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of study sample

Clinical profile

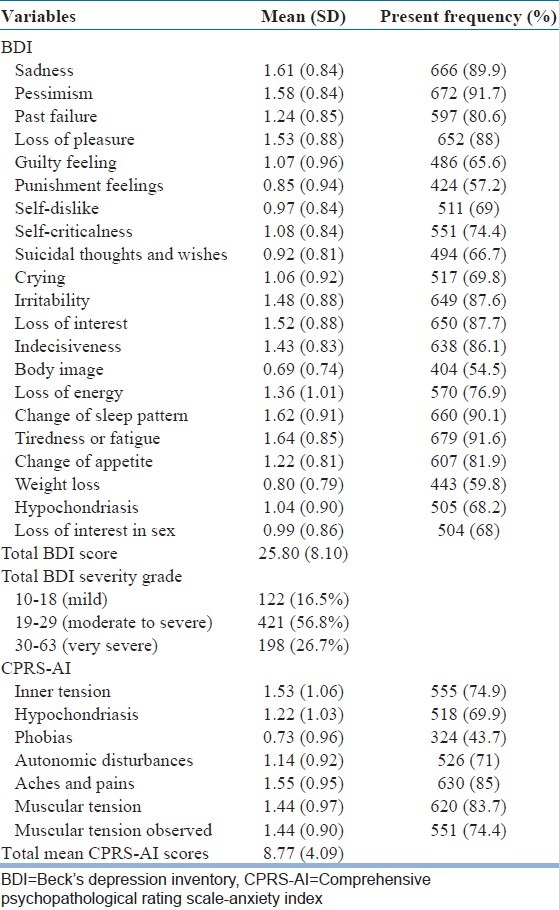

The mean duration of illness was 25.55 months (SD-43.12; range, 1-432 months; Median -12). Mean duration of illness was between 1-12 months for 58.3% of cases, 1-5 years for 34.1% of cases, and more than 5 years for 7.6% of cases. The mean BDI score for the study sample was 25.80 (SD-8.1). Most of the patients (56.8%) had moderate to severe depression as per BDI and slightly more than one-fourth (26.7%) had very severe depression. Table 2 shows the frequency/prevalence and severity of each depressive symptom as per BDI. The most common depressive symptoms were pessimism (91.7%), followed by fatigue (91.6%) and change in sleep pattern (90.1%). The mean CPRS-AI score was 8.77 (SD-4.09). In terms of frequency, aches and pains (85%) were the most common anxiety symptoms followed by muscular tension (83.7%).

Table 2.

Rating of study participants as per Beck's depression inventory and comprehensive psychopathological rating scale-anxiety index

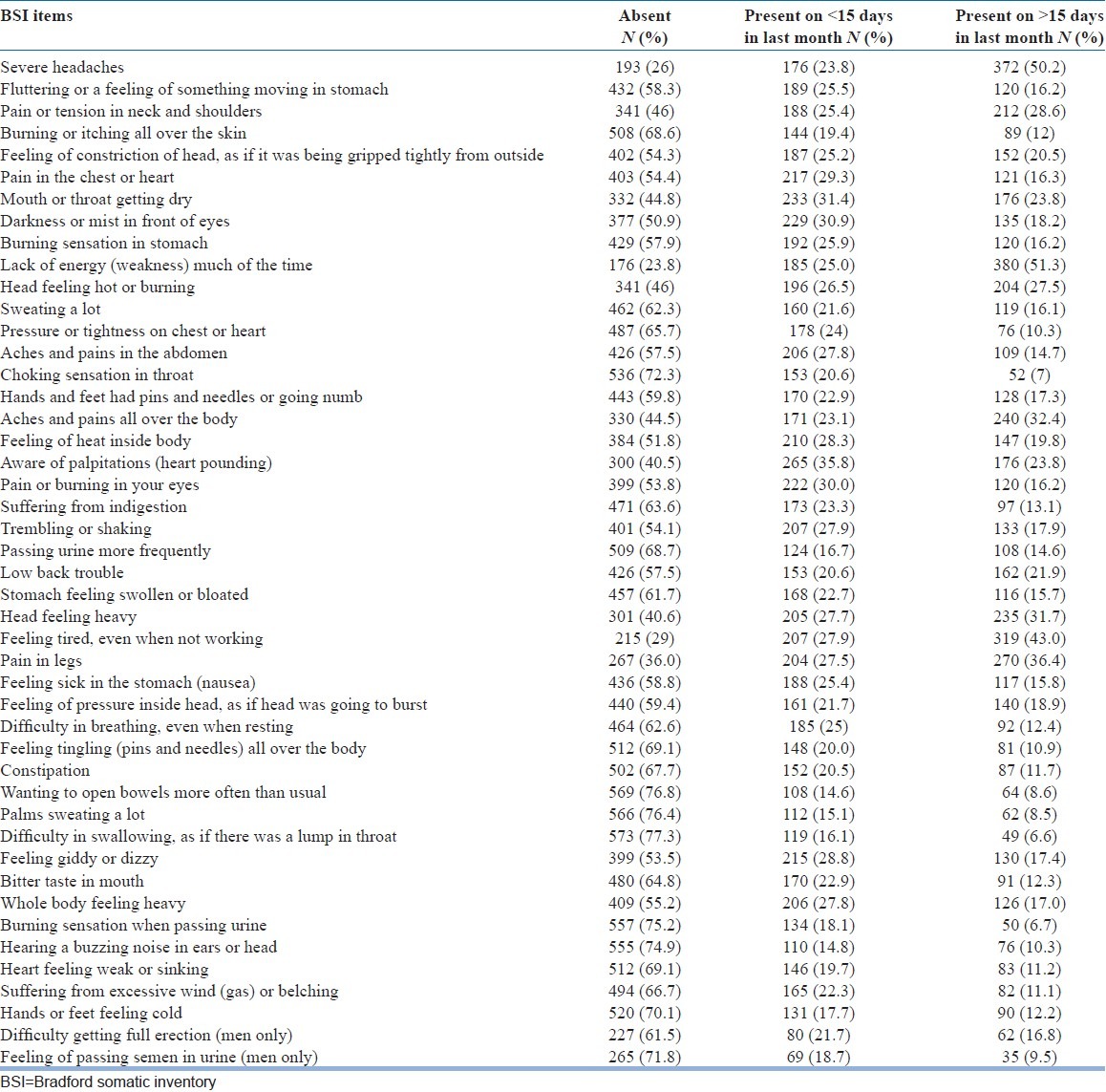

Frequency and typology of functional somatic symptoms as per BSI

The more commonly reported FSCs were lack of energy (weakness) much of the time (76.2%), severe headache (74%), and feeling tired when not working (71%). Other details as per BSI are shown in Table 3. The more common FSCs reported to be present for more than 15 days during the previous month were lack of energy (weakness) much of the time (51.3%), severe headache (50.2%), feeling tired when not working (43%), pain in legs (36.4%), aches and pains all over the body (32.4%), feeling of constriction of the head (32%), head feeling heavy (31.7%), pain or tension in neck and shoulders (28.6%), head feeling hot or burning (27.5%), aware of palpitations (23.8%), and dryness of mouth and throat (23.8%). The mean total BSI score was 27.42 (SD-15.38; range, 1-89). The mean number of FSCs was 19.05 (SD-10.22). Most of the patients (77%) had more than 10 FSCs, with 39.7% having more than 20 FSCs as per BSI.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of individual functional somatic complaint as per Bradford Somatic Inventory

Relationship of functional somatic symptoms with sociodemographic and clinical variables

Even though assessment of males included 2 extra BSI items, the total BSI score for males was less (26.26; SD-15.68) as compared to females (28.57; SD-15.01) and the difference between the 2 genders was statistically significant (t=2.04; P=0.04). Although mean number of FSCs were higher in females (19.77; SD-9.95) as compared to males (18.327; SD-10.44), the difference between the two groups was not significant. However, this became significant when the 2 symptoms which were exclusively evaluated in males were excluded (19.77±9.95 vs. 17.66±10.17; t-test value=2.85; P=0.004). Total BDI score was also significantly higher for females (26.84±8.8 vs. 24.95±7.31; t-test value=3.17; P=0.002). However, there was no significant difference in the total CPRS-AI score. None of the symptom assessed in participants of both the genders was significantly more frequent in males compared to females. The symptoms which were significantly more frequent in females were pain or tension in neck and shoulders (61.3% vs. 46.1%; Chi square value=16.06; P<0.001), pain in chest or heart (53.2% vs. 37.9%; Chi square value=17.44; P<0.001), choking sensation in the throat (31% vs. 24.4%; Chi square value=3.94; P=0.047), hands and feet had pins and needles or going numb (45.7% vs. 34.7%; Chi square value=9.34; P=0.002), aches and pains all over the body (59.7% vs. 51.2%; Chi square value=5.36; P=0.021), feeling of heat inside the body (53% vs. 43.4%; Chi square value=6.83; P=0.009), aware of palpitations (63.2% vs. 55.8%; Chi square value=4.14; P=0.042), low back trouble (47.3% vs. 37.7; Chi square value=7.04; P=0.008), stomach felt swollen or bloated (42.2% vs. 34.4%; Chi square value=4.75; P<0.029), head feeling heavy (66.7% vs. 52%; Chi square value=16.44; P<0.001), feeling tired even when not working (76.3% vs. 65.6%; Chi square value=10.41; P=0.001), pain in legs (71.2% vs. 56.6%; Chi square value=17.12; P<0.001), feeling sick in the stomach (46.5% vs. 35.8%; Chi square value=16.44; P=0.003), feeling of pressure inside head as if head was going to burst (46.5% vs. 34.7%; Chi square value=10.72; P=0.001), feeling giddy or dizzy (51.34% vs. 41.7%; Chi square value=6.87; P=0.009), and hands and feets feeling cold (35% vs. 24.7%; Chi square value=9.36; P=0.002).

Patients from rural background had significantly higher BSI total score (29.09±16.25 vs. 25.94±14.43; t-test value=2.79; P=0.005) and higher BDI score (27.01±7.8 vs. 24.9±8.31; t-test value=3.54; P<0.001). However, although mean number of FSCs were higher in patients from the rural background (19.77; SD-10.61 vs. 18.41; SD-9.82), the difference between the two groups was not significant. There was no significant difference in the CPRS-AI score. Patients from rural locality more frequently reported symptoms of feeling of constriction of head as if it was being gripped tightly from outside (49.6% vs. 42.3%; Chi square value=3.88; P=0.049), felt aches and pains all over the body (60.2% vs. 51.3%; Chi square value=5.91; P=0.015), passing urine more frequently (35.5% vs. 27.6%; Chi square value=5.46; P=0.019), stomach felt bloated or swollen (43.8% vs. 33.4%; Chi square value=8.48; P=0.004), felt tingling all over the body (36.4% vs. 26%; Chi square value=9.29; P=0.002), hearing a buzzing noise in the ears or head (30.7% vs. 20.1%; Chi square value=10.83; P=0.001), heart felt weak or sinking (35.2% vs. 27.04%; Chi square value=5.81; P=0.016), and excessive wind or bleaching (37.2% vs. 29.8%; Chi square value=4.55; P=0.033). Patients from urban locality more frequently reported symptoms of pain in chest or heart (49.23% vs. 41.54%; Chi square value=4.39; P=0.036) and whole body felt heavy (49% vs. 40.1%; Chi square value=5.86; P=0.015).

With regard to education, there was no significant difference in the total BSI, number of FSCs, total BDI and CPRS-AI score. On BSI, those educated less than high school more frequently reported the symptoms of felt lack of energy much of the time (81% vs. 73.4%; Chi square value=5.47; P=0.019), aches and pain all over the body (62% vs. 51.6%; Chi square value=7.61; P=0.006), feeling tired even when not working (75.5% vs. 68.3%; Chi square value=4.39; P=0.03), and difficulty in swallowing, as if there was a lump in throat (27.4% vs. 19.9%; Chi square value=5.47; P=0.019). Those educated up to or beyond high school more frequently reported low back trouble (45.6% vs. 37.2%; Chi square value=4.96; P=0.02).

Compared to those with higher income, patients with lower income (patient income less than 7323 rupees per month) had significantly higher number of FSCs (19.54±10.48 vs. 16.38±8.55; t-test value=3.76; P<0.001), total BSI score (28.67±16.1 vs. 23.89±12.47; t-test value=3.74; P<0.001), and higher total BDI score (26.41±8.08 vs. 24.43±8.15; t-test value=2.93; P=0.003).

Compared to those from higher socioeconomic status, patients from lower strata had significantly more frequent severe headaches (76.1% vs. 67.9%; Chi square value=5.0; P=0.025), fluttering or a feeling of something moving in stomach (45.8% vs. 30%; Chi square value=14.56; P<0.001), burning or itching all over the skin (34.7% vs. 22.3%; Chi square value=10.16; P=0.001), pain in the chest or heart (48.5% vs. 37.3%; Chi square value=7.26; P=0.007), head feeling hot or burning (57% vs. 45.6%; Chi square value=7.38; P=0.007), aches and pains in the abdomen (46.3% vs. 31.6%; Chi square value=12.69; P<0.001), choking sensation in throat (31% vs. 18.1%; Chi square value=11.84; P=0.001), hands and feet had pins and needles or going numb (44.3% vs. 28.5%; Chi square value=14.9; P<0.001), aches and pains all over the body (61% vs. 39.9%; Chi square value=25.61; P<0.001), pain or burning of eyes (48.3% vs. 39.9%; Chi square value=4.11; P=0.043), stomach feeling swollen or bloated (41.8% vs. 28.5%; Chi square value=10.66; P=0.001), pain in legs (67.9% vs. 52.8%; Chi square value=13.99; P<0.001), feeling sick in the stomach (nausea) (43.8% vs. 33.7%; Chi square value=6.03; P=0.014), feeling tingling (pins and needles) all over the body (33.4% vs. 23.8%; Chi square value=6.1; P=0.013), bitter taste in mouth (39.6% vs. 22.8%; Chi square value=17.65; P<0.001), and suffering from excessive wind (gas) or belching.

There was no significant difference in the total BSI, number of FSCs, and total BDI scores between Hindus and Muslims. However, total CPRS-AI score was significantly higher for Hindus (9.55±4.31 vs. 7.99±4.08; t-test value=3.72; P<0.001). When compared to Hindus, Muslims more frequently reported darkness or mist in front of the eyes (54.7% vs. 43.6%; Chi square value=5.16; P=0.023), head felt hot or burning (54.7% vs. 41.7%; Chi square value=7.1; P=0.008), bitter taste in the mouth (41.6% vs. 29.8%; Chi square value=6.48; P=0.011), and passing semen in urine (21.9% vs. 10.96%; Chi square value=10.64; P=0.001). On the contrary, compared to Muslims, Hindus more frequently reported lack of energy (weakness) much of the time (73% vs. 86.7%; Chi square value=12.33; P<0.001), sweating a lot (38.1% vs. 24.8%; Chi square value=8.09; P=0.004), and palms sweating a lot (28.2% vs. 19.7%; Chi square value=3.86; P=0.049).

Total BSI score (28.05±15.51 vs. 16.48±9.58; t-test value=5.15; P<0.001), total BDI score (26.24±8.65 vs. 23.46±5.52; t-test value=2.22; P=0.027), and total CPRS-AI score (9.55±4.31 vs. 6.34±3.31; t-test value=5.08; P<0.001) were significantly lower for Sikhs, when compared to Hindus. However, mean number of FSCs as per BSI were significantly lower for Sikhs (12.44±8.28 vs. 19.00±10.42; t-test value=4.28; P<0.001). On BSI, when compared to Sikhs, Hindus more frequently reported severe headache (69.4% vs. 48%; Chi square value=9.31; P=0.002), feeling of constriction of head as if it was being gripped tightly from outside (52.4% vs. 24%; Chi square value=14.39; P<0.001), mouth or throat felt dry (57.6% vs. 324%; Chi square value=11.81; P=0.001), reported lack of energy (weakness) much of the time (86% vs. 56%; Chi square value=28.33; P<0.001), sweating a lot (38.1% vs. 18%; Chi square value=28.33; P<0.001), hands and feet had pins and needles or going numb (41.9% vs. 16%; Chi square value=12.62; P<0.001), aches and pains all over the body (61.8% vs. 44%; Chi square value=5.9; P<0.015), aware of palpitations (64.4% vs. 28%; Chi square value=24.88; P<0.001), indigestion (38.4% vs. 16%; Chi square value=9.72; P=0.002), trembling or shaking (47.9% vs. 28%; Chi square value=7.01; P=0.008), passing urine more frequently (32.5% vs. 14%; Chi square value=7.18; P=0.007), low back trouble (48.1% vs. 8%; Chi square value=29.2; P<0.001), stomach felt swollen or bloated (37.2% vs. 22%; Chi square value=4.50; P=0.03), head feeling heavy (61.6% vs. 44%; Chi square value=5.76; P<0.016), feeling tired even when not working (71.8% vs. 54%; Chi square value=6.73; P=0.009), feeling pressure in the head as if it is going to burst (41% vs. 24%; Chi square value=5.41; P=0.02), tingling (needle and pin) all over the body (33.9% vs. 12%; Chi square value=9.91; P=0.002), constipation (35.3% vs. 20%; Chi square value=4.68; P<0.03), palms sweating a lot (28.2% vs. 14%; Chi square value=4.6; P<0.032), difficulty in swallowing as if there is a lump in the throat (23.2% vs. 6%; Chi square value=7.88; P=0.005), feeling giddy or dizzy (51.6% vs. 10%; Chi square value=31.12; P<0.001), whole body feeling heavy (44.5% vs. 18%; Chi square value=12.95; P<0.001), hearing a buzzing noise in ears or head (27.5% vs. 4%; Chi square value=13.15; P<0.001), heart felt weak or sinking (34.4% vs. 12%; Chi square value=10.27; P=0.001), excessive wind (gas) or belching (32% vs. 18%; Chi square value=4.12; P<0.042), and hands and feet feeling cold (32.5% vs. 16%; Chi square value=5.69; P<0.017). On the contrary, compared to Hindus, Sikhs more frequently reported head felt hot or burning (62% vs. 41.7%; Chi square value=7.87; P=0.005) and pain in the legs (72% vs. 56.2%; Chi square value=4.59; P=0.032).

Overall, there was no significant difference between the total BSI, total number of FSCs, and total BDI scores between Hindus and Christians. However, total CPRS-AI was significantly higher for Hindus (9.55 vs. 7.68; t- test value=2.73; P=0.007). Compared to Hindus, Christian more frequently reported severe headache (100% vs. 69.43%; Chi square value with Yate's correction=15.88; P<0.001), fluttering or feeling of something moving in the stomach (56.1% vs. 38.1%; Chi square value=5.01; P=0.025), skin burning or itching all over (63.4% vs. 23.2%; Chi square value=30.78; P<0.001), felt pain in chest or heart (70.7% vs. 40.3%; Chi square value=14.13; P<0.001), sweating a lot (56.1% vs. 38.15%; Chi square value=5.02; P=0.02), feeling heat inside the (75.6% vs. 45.5%; Chi square value=13.57; P<0.001), felt pain or burning in the eyes (56.1% vs. 39.6%; Chi square value=4.21; P=0.04), pain in legs (87.8% vs. 56.16%; Chi square value=15.46; P<0.001), difficulty in breathing even when at rest (58.5% vs. 32%; Chi square value=11.67; P=0.001), bitter taste in the mouth (46.3% vs. 29.8%; Chi square value=4.72; P=0.03), and burning sensation in the urine (34.14% vs. 20.6%; Chi square value=4.01; P=0.045). When compared to Christians, Hindus more frequently reported feeling of constriction of head, as if it was being gripped tightly from outside (52.4% vs. 24.9%; Chi square value=11.7; P=0.001), reported lack of energy (weakness) much of the time (86% vs. 48.8%; Chi square value=36.25; P<0.001), head felt hot or burning (85.4% vs. 41.7%; Chi square value=28.71; P<0.001), aches and pains all over the body (61.8% vs. 31.7%; Chi square value=14.05; P<0.001), constipation (35.3% vs. 12.2%; Chi square value=8.99; P=0.003), feeling giddy or dizzy (51.6% vs. 34.1%; Chi square value=4.58; P=0.032), and difficulty in getting erection (20.4% vs. 2.4%; Chi square value with Yates Correction=6.75; P=0.005).

Clinical variables

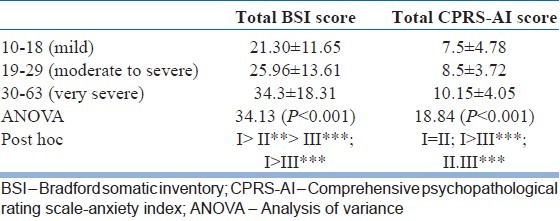

When total BSI and total CPRS scores were compared between different severities of depression as assessed by BDI, it was seen that there was significant difference in the total BSI score between the different depression categories. With regard to anxiety, there was no significant difference between the mild depression and the moderate to severe depression groups, but those with very severe depression had significantly higher anxiety scores too. The results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Relationship of severity of depression with Bradford Somatic Inventory and comprehensive psychopathological rating scale-anxiety index

When the frequency of BSI symptoms were compared across the depression severity groups, in general, all the symptoms were significantly more frequent in the moderate to severe depression and very depressed groups, compared to mild depression group except for the symptoms of burning or itching all over the skin, sweating a lot, hands and feet have pins and needle like sensation or gone numb, felt pain or burning in the eyes, indigestion, stomach felt swollen or bloated, constipation, wanted to open bowel more often than usual, burning sensation while passing urine, excessive wind (gas) or bleaching, hands and feet feeling cold, and passing semen in the urine.

With regard to clinical correlates, there was positive correlation between total BSI score and total BDI score (Pearson Product moment correlation value=0.321; P=0.001) and total BSI score and total CPRS-AI score (Pearson Product moment correlation value=0.413; P=0.001). Total BDI score also had positive correlation with total CPRS-AI score (Pearson Product moment correlation value=0.256; P<0.001). Total number of FSCs also had positive correlation with total BDI score (Pearson Product moment correlation value=0.258; P<0.001) and total CPRS-AI (Pearson Product moment correlation value=0.377; P<0.001).

Total duration of illness did not have any significant association with total BSI score. However, there was positive correlation between total duration of illness and total BDI score (Pearson Product moment correlation value=0.321; P=0.001), and negative correlation with total CPRS-AI score (Pearson Product moment correlation value=-0.076; P=0.038). There was no correlation of total BSI score, total BDI score, total CPRS-AI with the age of onset and the duration of illness.

DISCUSSION

This is the first multicentric study funded by the Indian Psychiatric Society. At one level, this was also a feasibility study, which tried to evaluate whether multicentric studies with low funding resources are possible or not. The study involved 16 centers across various treatment settings. It was desired that at least each center recruits 50 patients and it was seen that except for 3 centers, most of the centers recruited about 50 patients. This suggests that if concerted efforts are made, multicentric studies can be done with reasonable amount of funding.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the typology of first episode depression. The study included 741 subjects with reasonable representation from each zone of the country. The mean age of the patients was about 38 years, with about 80% of patients in the age group of 21 to 50 years. There was nearly equal gender distribution and those from urban and rural backgrounds also had nearly equal distribution. Majority of the participants were married, Hindus, educated up to or beyond high school level, were employed, were earning less than 7322 rupees, and belonged to nuclear families. This sociodemographic profile is similar to other studies from India which has evaluated patients of depression.[25,26] Although the mean duration of illness was 25.55 months, the median was 12 months, which is similar to the mean reported in earlier studies which have evaluated FSC in depression.[25,26] Majority of the patients had moderate to severe depression, as seen in earlier studies.[19,25,26] The mean BDI score for the study sample was 25.80 (SD-8.1), which is higher than that reported by Chakraborty et al.,[25] suggesting that the severity of depression of patients included in this study was greater. However, the mean CPRS-AI score was 8.77, which is similar to that reported in an earlier study.[25]

The most commonly reported FSCs were lack of energy (weakness) much of the time (76.2%), severe headache (74%), and feeling tired when not working (71%). Other commonly reported symptoms present in about half of the sample were pain in legs (64%), aware of palpitations (59.5%), head feeling heavy (59.4%), aches and pains all over the body (55.5%), mouth or throat getting dry (55.2%), pain or tension in neck and shoulder (54%), head feeling hot or burning (54%), and darkness or mist in front of the eyes (49.1%). This profile of FSCs is quite similar to that reported in an earlier study from India which evaluated FSC using BSI in a small sample size.[25] Other study which evaluated FSC using PHQ-15 also reported a similar profile. Studies from the West, which have evaluated FSCs across various settings using different instruments like somatic symptom inventory (SSI) and self report 90 item symptom checklist, have also reported high prevalence of different painful symptoms, as noted in the present study.[17–19,38] The above similarities suggest that many FSCs are present in patients with depression, which are specifically not included in the nosological systems and these FSCs are present across different cultures and different treatment settings. Current nosological systems (DSM-IV[32] and ICD-10[39] ) include FSCs like feeling tired, having low energy and trouble sleeping as part of the diagnostic criteria of depression. Many other FSCs, especially the painful symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms and autonomic symptoms are not included in the nosological systems. Hence, in future the nosological systems should give adequate weightage to these symptoms and some of the common FSC could be given weightage in the diagnostic criteria for depression. This would possibly improve the identification of depression in primary care setting. Furthermore, the findings of the study also suggest that clinicians should routinely look for FSCs while assessing patients with depression and various clinical trials should also take these complaints into account while evaluating the efficacy of various antidepressants in patients of depression.

The mean total BSI score in the present study was 27.42 which was more than that reported in an earlier study.[25] The mean number of FSCs was 19.05 (SD-10.22), with most of the patients (77%) having more than 10 FSCs. These figures are more than the number of FSCs reported by Grover et al.[26] However, this can be understood in light of the fact that PHQ-15 covers only 15 symptoms, whereas the BSI has wider coverage and includes 46 symptoms.

Reasonably larger sample of the present study allowed us to evaluate the sociodemographic and clinical variables associated with FSCs in depression. With regard to clinical variables, it was seen that the severity and number of total FSCs had positive correlation with severity of depression as assessed by BDI and CPRS-AI. Similar correlations between FSCs, especially painful symptoms and severity of depression[17,19,25,26,38,40] and anxiety,[7,40–43] have been reported in various studies across the globe. However, few studies conducted in different treatment settings do not support the positive association between severity of depression and prevalence of FSCs.[5,6,33,44] Similarly, the positive correlation between anxiety levels and severity of FSCs is contradictory to that reported in the earlier study from India, which included a smaller sample size.[25] Overall, there is more evidence to suggest the positive association between prevalence of FSC and severity of depression. Hence, the association of severity and number of FSCs with severity of depression and anxiety suggests that these symptoms are part and parcel of depression.

With regard to sociodemographic variables, total BSI score and mean number of FSCs were significantly higher for females. This finding is supported by previous studies which have reported higher prevalence of FSCs in females.[40,45–47] Similar finding of higher prevalence of FSCs in females have been reported in an earlier study from India,[27] whereas other studies have reported higher prevalence in males.[28,30] However, it is important to note that the latter studies did not assess specifically the patients of depression. Two studies from India which assessed the patients of depression reported no difference between the gender;[25,26] however, these studies had relatively smaller sample size compared to the present study. Furthermore, females more frequently had symptoms of pain or tension in neck and shoulders, pain in chest or heart, choking sensation in the throat, hands and feet had pins and needles or going numb, aches and pains all over the body, feeling of heat inside the body, aware of palpitations, low back trouble, stomach felt swollen or bloated, head feeling heavy, feeling tired even when not working, pain in legs, feeling sick in the stomach, feeling of pressure inside head as if head was going to burst, feeling giddy or dizzy, and hands and feet feeling cold. The previous study, which evaluated FSCs by using PHQ-15, also reported higher prevalence of back pain and pain in arms, legs, or joints in females.[26] These findings need to be evaluated further, so as to have better understanding about manifestation of depression in patients with either gender. In the present study, patients from rural background had significantly higher BSI total score and higher number of total BSI symptoms, compared to those from the urban background. These findings suggest that the manifestation of depression is to a certain extent influenced by the locality of residence. Previous studies have not evaluated such relationship and in future, it would be useful to look at this relationship. In the present study, there was no significant difference in the number of FSCs and severity of FSCs between those educated less than high school and those educated up to or beyond high school. This is contradictory to the studies from the West.[40,45–47] Presence of higher number of FSCs in those from lower socioeconomic status is supported by findings from the West.[40,45–47]

Certain differences in the prevalence and type of FSCs were also seen in patients from different religion. Although previous studies have looked at the differences in other symptoms of depression, for example, suicidal behavior, no study has looked at the difference in manifestation of FSCs across different religious affiliations.

There are certain limitations of the present study in the form of cross-sectional design and lack of assessment of other clinical correlates of depression. The study was also limited to only treatment seeking patients attending the mental healthcare facilities. Relationship of FSCs with treatment adherence, drug compliance and help-seeking behavior was not studied. Future studies should attempt to overcome these limitations. Research in this area should also focus on developing effective interventions for FSCs in patients of depression.

To conclude, this study suggests that FSCs are highly prevalent in patients diagnosed with major depressive episode. Most of the patients have more than 10 FSCs and the common FSCs are lack of energy (weakness) much of the time, severe headache and feeling tired when not working, pain in legs, aware of palpitations, head feeling heavy, aches and pains all over the body, mouth or throat getting dry, pain or tension in neck and shoulder, head feeling hot or burning, and darkness or mist in front of the eyes. When one compares the findings of the present study with literature, this study also suggests that the type of FSCs are similar to certain extent across different cultures. The prevalence and type of FSC in patients with depression is to a certain extent associated with sociodemographic variables and severity of depression. In view of the high prevalence of FSCs in depression, it is important to include these symptoms in the diagnostic criteria of depression, so as to increase the sensitivity and specificity of the diagnosis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Llyod G. Medicine without signs. BMJ. 1983;287:539–54. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6391.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fifer SK, Buesching DP, Henke CJ, Potter LP, Mathias SD, Schonfeld WH, et al. Functional status and somatization as predictors of medical offset in anxious and depressed patients. Value Health. 2003;6:40–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2003.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg PE, Leong SA, Birnbaum HG, Robinson RL. The economic burden of depression with painful symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luber MP, Meyers BS, Williams-Russo PG, Hollenberg JP, DiDomenico TN, Charlson ME, et al. Depression and service utilization in elderly primary care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:169–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Linzer M, Hahn SR, deGruy FV, 3rd, et al. Physical symptoms in primarycare: Predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. ArchFam Med. 1994;3:774–9. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dworkin SF, Von Korff M, Le Resche L. Multiple pains and psychiatric disturbance: An epidemiological investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:239–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810150039007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon GE, Vonkorff M. Somatization and psychiatric disorder in the NIMH Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1494–500. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.11.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zwaigenbaum L, Szatmari P, Boyle MH, Offord DR. Highly somatizing young adolescents and the risk of depression. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1203–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terre L, Poston WS, Foreyt J, St Jeor ST. Do somatic complaints predict subsequent symptoms of depression? Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72:261–7. doi: 10.1159/000071897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ising M, Lauer CJ, Holsboer F, Modell S. The Munich vulnerability study on affective disorders: Premorbid psychometric profile of affected individuals. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:332–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon GE, Vonkorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1329–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirmayer LJ, Robbins JM, Dworkind M, Yaffe MJ. Somatisation and the recognition of depression and anxiety in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:734–41. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain co morbidity: A literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2433–45. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton M. Frequency of symptoms in melancholia (depressive illness) Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:201–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Eckert GJ, Stang PE, Croghan TW, Kroenke K. Impact of pain on depression treatment response in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:17–22. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000106883.94059.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tylee A, Gastper M, Lepine JP, Mendlewicz J. DEPRES II (Depression Research in European Society II): A patient survey of the symptoms, disability, and current management of depression in the community.DEPRES Steering Committee. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14:139–51. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199905002-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muñoz RA, McBride ME, Brnabic AJ, López CJ, Hetem LA, Secin R, et al. Major depressive disorder in Latin America: The relationship between depression severity, painful somatic symptoms, and quality of life. J Affect Disord. 2005;86:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugahara H, Akamine M, Kondo T, Fujisawa K, Yoshimasu K, Tokunaga S, et al. Somatic symptoms most often associated with depression in an urban hospital medical setting in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 2004;126:151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corruble E, Guelfi JD. Pain complaints in depressed inpatients. Psychopathology. 2000;33:307–9. doi: 10.1159/000029163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathew NT, Reuveni U, Perez F. Transformed or evolutive migraine. Headache. 1987;27:102–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1987.hed2702102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Lipscomb P, Russo J, Wagner E, et al. Distressed high utilizers of medical care.DSM-III-R diagnoses and treatment needs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1990;12:355–62. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(90)90002-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerber PD, Barrett JE, Barrett JA, Oxman TE, Manheimer E, Smith R, et al. The relationship of presenting physical complaints to depressive symptoms in primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:170–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02598007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juang KD, Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR, Su TP. Comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders in chronic daily headache and its subtypes. Headache. 2000;40:818–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posse M, Hallstrom T. Depressive disorders among somatizing patients in primary health care. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;98:187–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakraborty K, Avasthi A, Kumar S, Grover S. Psychological and clinical correlates of functional somatic complaints in depression. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2012;58:87–95. doi: 10.1177/0020764010387065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grover S, Kumar V, Chakrabarti S, Hollikatti P, Singh P, Tyagi S, et al. Prevalence and type of functional somatic symptoms in patients with first episode depression. East Asian Archives Psychiatry. 2012;22:146–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gautam SK, Kapur RL. Psychiatric patients with somatic complaints. Indian J Psychiatry. 1977;19:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srinivasan K, Srinivasa Murthy R, Janakiramaiah N. A nosological study of patients presenting with somatic complaints. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1986;73:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb02656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaturvedi SK, Michael A, Sarmukaddam S. Somatizers in psychiatric care. Indian J Psychiatry. 1987;29:337–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banerjee G, Sinha S, Mukherjee DG, Sen G. A study of psychiatric disorders other than psychosis in the referred cases with somatic complaints. Indian J Psychiatry. 1987;29:363–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pereira B, Andrew G, Pedneker S, Pai R, Pelto P, Patel V. The explanatory models of depression in low income countries: Listening to women in India. J Affect Disord. 2007;102:209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.4th ed Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mumford DB, Bavington JT, Bhatnagar KS, Hussain Y, Mirza S, Naraghi MM. The Bradford Somatic Inventory: A multi-ethnic somatic inventory reported by anxious and depressed patients in Britain and Indo-Pakistan subcontinent. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:379–86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.158.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lecrubier Y, Sheehan D, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Sheehan K, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)-a short diagnostic structured interview: Reliability and validity according to CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:224–31. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amorim P, Lecrubier Y, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Sheehan D. DSM-III-R psychotic disorders: Procedural validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). Concordance and causes for discordance with the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13:26–34. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)86748-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck AT, Ward C, Mendelson M. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asberg M, Montgomery SA, Perris C, Schalling D, Sedvall G. The comprehensive psychopathological rating scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1978;271:5–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1978.tb02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaccarino AL, Stills TL, Evans KR, Kalali AH. Prevalence and association of somatic symptoms in patients with Major Depressive Disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;110:270–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geneva: WHO; 1992. World Health Organization: The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders-Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sayar K, Kirmayer LJ, Taillefer SS. Predictors of somatic symptoms in depressive disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:108–14. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haug TT, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. The association between anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms in a large population: The HUNT-II study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:845–51. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000145823.85658.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fink P, Ewald H, Jensen J, Sørensen L, Engberg M, Holm M, et al. Screening for somatization and hypochondriasis in primary care and neurological inpatients: A seven- item scale for hypochondriasis and somatization. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46:261–73. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kroenke K, Price R. Symptoms in the community.Prevalence, classification and psychiatric comorbidity. Arch Inten Med. 1993;153:2474–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westermeyer J. Psychiatric epidemiology across cultures: Current issues and trends. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review. 1989;26:5–25. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. Gender differences in the reporting of physical and somatoform symptoms. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:150–5. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199803000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stewart DE. Physical symptoms of depression: Unmet needs in special populations. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 7):12–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wool CA, Barsky AJ. Do women somatize more than men. Gender differences in somatization? Psychosomatics. 1994;35:445–52. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(94)71738-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]