Abstract

Background:

Stress has touched almost all professions posing threat to mental and physical health. India being the Information Technology (IT) hub with lakhs involved as IT Professionals, there is a need to assess prevalence of professional stress, depression and problem alcohol use and understand their association.

Objectives:

(1) To screen for the prevalence of professional stress, risk for depression and harmful alcohol use among software engineers. (2) To study the association between professional stress, risk for depression and harmful alcohol use.

Materials and Methods:

This is a cross-sectional online study conducted using screeing questionnaires like professional life stress scale, centre for epidemiological studies depression scale and alcohol use disorders identification test. This study was conducted specifically on professionals working in an IT firm with the designation of a software engineer.

Results:

A total of 129 subjects participated in the study. 51.2% of the study sample was found to be professionally stressed at the time of the interview. 43.4% of the study population were found to be at risk for developing depression. 68.2% of those who were professionally stressed were at risk for developing depression compared with only 17.5% of those who were not professionally stressed. Odds ratio revealed that subjects who were professionally stressed had 10 times higher risk for developing depression compared to those who were not professionally stressed. Subjects who were professionally stressed had 5.9 times higher prevalence of harmful alcohol use compared to those who were not professionally stressed. Subjects who were at risk for developing depression had 4.1 times higher prevalence of harmful alcohol use compared with those who were not at risk for developing depression.

Conclusion:

Such higher rates of professional stress, risk for developing depression and harmful alcohol use among software engineers could hinder the progress of IT development and also significantly increase the incidence of psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: Alcohol use, alcohol use disorders identification test, depression, depression and alcohol use, IT professionals, occupational stress, professional stress, software engineers, stress, stress among IT professionals, stress and alcohol use, stress and depression, work place stress

INTRODUCTION

Stress has touched almost all professions posing threat to mental and physical health. Work related stress in the employee, consequently affects the health of the entire organization.[1] National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, part of U.S Department of Health and Human Services, states that “job stress, now more than ever, poses a greater threat to the health of workers and the health of the organisations”.[2] Interest in professional stress research is growing primarily because of the increasing incidence of the adverse effects of profession on psychological and physical health of emplyoees.[3] IT company jobs are known to be more competitive and stressful because of their nature of work like target achievements, night shift, work overload.[1] Also software development process is a learning and communication process requiring greater interaction with the clients, deep understanding of the business process, and insight into technological innovations. These situations puts pressure on the professionals resulting in professional stress.[4] India being a forerunner in the IT industry with lakhs involved as IT professionals. There is an urgent need to understand the dynamics of the IT professional stress and its associated psychiatric morbidities so as to prevent it from assuming epidemic proportion. No available study has been done in India which screened and associated professional stress, risk for developing depression and harmful alcohol use among IT Professionals.

Objectives

To screen for the prevalence of professional stress, risk for developing depression and harmful alcohol use among software engineers.

To study the association between professional stress, risk for developing depression and harmful alcohol use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a cross-sectional online study. Screeing questionnaires were used to identify software engineers who are professionally stressed, those who are at risk for developing depression and those with harmful alcohol use. This survey used Snowball technique of sampling. Study was conducted specifically on professionals working in an IT firm with the designation of software engineer. To enable data gathering, an online survey website was utilised. Participants were explained the objectives of the study and only those who gave consent were given the option to take up the interview. Subjects who reported to be on psychiatric treatment were excluded. The interview link was sent to the software engineers working in different parts of India. The subject's name, company they work for, and the city of working were left optional to maintain anonymity and facilitate unbiased reporting. A total of 129 completed interview were obtained at the end of the study.

Measures used

Professional life stress scale:[5,6] It is a screening tool developed by David Fontana in 1989. It contains 22 questions which screens for professional stress by assessing various domains of profession like work load, work environment, rewards etc. The scoring range is between 0 and 60. Subjects who scores upto 15 are considered ‘not stressed’. Subjects with scores of 16 and above are considered to be stressed, and based on higher scores further classification of severity is given. In our study we have used this questionnaire to rule out the presence or absence of professional stress. Hence subjects with the score of 16 and above are considered as stressed and those with the score of 15 and below are considered as not stressed.

Center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CESD):[6–8] The 20-item CESD (CESD-20) is a screening questionnaire developed by Radolff L.S in 1977. Its components cover elements related to depressed mood, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, helplessness and hopelessness, psychomotor retardation, appetite loss and sleep disturbance. Responses capture the frequency of feelings and behaviours over the past 7 days and are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). An overall score is calculated by summing the scores and ranges between 0 and 60. Higher scores suggest greater levels of depressive symptoms. A score of 16 or higher has been used extensively as the cut-off point for high depressive symptoms on this scale. A cut score of 16 or greater is recommended for indicating depression in the previous week. In our study we have considered those subjects with the score of 16 and above as those ‘at risk’ for developing depression as our study was designed only to screen and no diagnostic startegies were taken.

Alcohol use disorders identification test:[9] The World Health Organization's alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) is a reliable and simple screening tool which is sensitive to early detection of risky and high risk (or hazardous and harmful) drinking. AUDIT incorporates questions about the quantity and frequency of alcohol use in adults. A score of 8 or more is associated with harmful or hazardous drinking. In our study subjects who scored 8 and above are considered as those with harmful alcohol use.

Statistical analysis

Both descriptive and inferential statistics were employed in the present study. Contingency coefficient tests were applied to study the association using SPSS for windows (version 16.0). Further Odd's Ratio's were calculated for risk estimation.

RESULTS

General characteristic of the population

A total of 129 subjects participated in the study. Out of them 77.5% were males and 22.5% were females. Male:Female ratio was 3.4:1.

Based on age distribution: 27.9% of the study sample were between 22 years and 25 years, 62% were between 26 years and 30 years, 9.3% were between 31 years and 35 years and only 0.8% above 36 years. Majority of the study sample were between the age of 22 years and 30 years.

Based on duration of work as software engineer: 3.9% of the study sample had work experience as software engineer for <6 months, 15.5% had work experience between 6 months and 2 years, 36.4% between 2 years and 4 years, 27.1% between 4 years and 6 years, 17% were working as software engineer for >6 years. Majority of the study sample had work experience of >6 months.

Based on marital status: 70.5% of the study sample were single at the time of interview, 21.7% were married and 7.8% were committed but not married. None reported to be in a live-in relationship.

Results of professional life stress scale

51.2% of the study sample was found to be professionally stressed at the time of the interview.

Gender: 51% of the male subjects and 51.7% of the female subjects were found to be professionally stressed.

Age distribution: 33.33% of those subjects between the age of 22 years and 25 years, 63.75% of those between 26 years and 30 years and 25% of those were between 31 years and 35 years were found to be professionally stressed. Significant difference was noted (P=0.003) in the distribution of professionally stressed individuals based on the age. Subjects between 26 years and 30 years of age had the highest prevalance of professional stress.

Duration of work as software engineer: 40% of those with work duration of <6 months were found to be professionally stressed, 35% of those between 6 months and 2 years, 53% of those between 2 years and 4 years, 65.7% of those between 4 years and 6 years and 40.9% of those above 6 years of work duration as software engineers were found to be professionally stressed. No significant difference among the groups was noted even though increase in the prevalence of professional stress with increasing duration of work was observed.

Marital status: 51.64% of those who were single, 50% of those who were married and 50% of those who were committed but not married were found to be professionally stressed.

Results of center for epidemiological studies depression scale

On screening for depressive symptoms 43.4% of the study population were found to be at risk for developing depression at the time of the interview.

Gender: 39% of males and 58.6% of females were at risk for developing depression.

Age: 36.1% of those between 22 years and 25 years, 51.2% of those between 26 and 30 years and 16.6% of those between 31 years and 35 years were found to be at risk for developing depression. Though no significant difference (P=0.07) was noted among the age groups, those between the age group of 26 years and 30 years were found to be at higher risk for developing depression.

Duration of work as software engineer: 20% of those working as software engineers from <6 month, 30% of those working between 6 months and 2 years, 53.1% of those between 2 years and 4 years, 48.5% of those between 4 years and 6 years, 31.8% of those above 6 years of work duration as software engineers were found to be at risk for developing depression.

Marital status: 43.9% of those who were single, 35.7% of those who were married and 60% of those who were committed but not married were found be at risk for developing depression.

Association between stress and at risk for depression

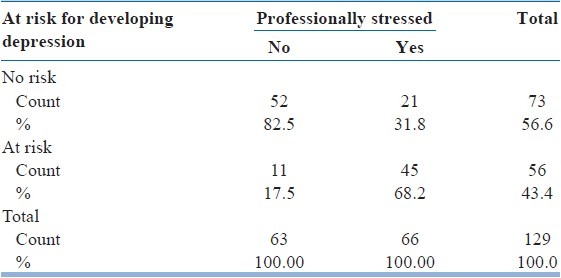

68.2% of those who were professionally stressed were at risk for developing depression whereas only 17.5% of those who were not professionally stressed were at risk for developing depression. Significance was noted (P=0.000).

Using odd's ratio we found that subjects who were professionally stressed had 10 times higher risk of developing depression compared with those who were not professionally stressed [Table 1].

Table 1.

Association between professionally stressed and at risk for developing depression subjects

Results of alcohol use disorders identification test

39.5% of the study sample reported that they consume alcohol. On interpretation of AUDIT score of 8 and above as harmful alcohol use, 14% of the study population were screened as having harmful alcohol use.

Association between subjects who were stressed and with harmful alcohol use

45.45% of those who were stressed professionally consumed alcohol compared to 33.33% of those who were not stressed. No significant difference was noted when just the alcohol consumption was compared between those who were professionally stressed and those who were not. But on using AUDIT interpretation, harmful drinking was present in 22.7% of those who were professionally stressed compared with 4.8% among those who were not stressed. Significant difference was noted (P=0.003).

Subjects who were professionally stressed had 5.9 times higher prevalence of harmful alcohol use compared with those who were not professionally stressed.

Association between subjects who were at risk for depression and with harmful alcohol use

Alcohol consumption was present in 39.28% of those who were at risk for developing depression and 39.72% of those who were not at risk for developing depression. No significant difference was noted when just the alcohol consumption was compared between those at risk and not at risk for developing depression. But on using AUDIT interpretation, harmful drinking was seen in 23.2% of those who were at risk for developing depression compared with 6.8% of those who were not at risk for developing depression, significant difference was observed between the two groups when harmful drinking was compared (P=0.008).

Subjects who were at risk for developing depression had 4.1 times higher prevalence of harmful alcohol use compared with those who were not at risk for developing depression.

DISCUSSION

In our study sample males were more in number than females. Other studies on IT professionals reflect similar findings. Studies in Europe reported that females accounted for only 25% of the technology professional and it was found be 20% in U.S technology workforce. The gender difference may be largely due to cultural and social influences.[10,11] Because of the variety of roles that women assume – wife, mother and caretaker during the peak periods of their professional and academic carrier, it might lead them to opt professions which are less time consuming and less stressful unlike IT profession.[12–14]

Among 129 subjects 66 of them (51.2%) were found to be professionally stressed. This high incidence of stress among IT professionals was observed in previous studies too. In an online survey done among South Indian software engineers reported that 32.4% of their study sample to be distressed and 8.1% had severe pschological stress.[15] Another study done on IT professionals in Delhi reported that 35% of their study subjects to be stressed.[16] Study done on women IT professionals in Chennai reported 55.22% of their study subjects to be experiencing moderate levels of stress, 28% of the study subjects had high overall stress and 1.6% had very high overall stress.[17] Job stress is a common workplace problem experienced by all professionals irrespective of their nature of work; however, this phenomenon is more common in professions that are driven by deadline. Software organisation is one such sector, which is affected profoundly by this challenge, and professionals serving these organizations are often under high stress. IT profession is characterised by various factors that can lead to increased stress like constant change in technology, client interaction, fear of obsolescence, family support, long working hours, work overload etc.[18] This profession is also known to be volatile and faces the problem of lack of job security and the need for constant upgradation of skills to remain marketable. Thong and Yap in their study opined that though pay structure is relatively higher compared with other sectors, the working conditions in the IT Profession is becoming more and more stressful.[19]

When professionally stressed individuals were assessed based on the age, significant difference was noted, with the age group of 26-30 being highly stressed compared with other age groups. Study done among IT professionals in Pakistan reported similar findings that age group between 25 years and 28 years to be highly stressed compared to other age groups.[20] This age group is under the transition from single to marital status and along with their already existing possibly stressful daily job chores they have to adapt to marital life. Role overload as most of them will be promoted to the post of senior software engineers in this age group and the need to cope with changing expectations at work and family place adds to the presure. This age group is also involved in pursuing further education, thus adding to the burden. The above factors can be some of the possible explanations for the higher prevalence of stress in this age group.

Professional stress was observed to increase with increase in experience, i.e., duration of work as software engineer. A similar finding was reported by an earlier study that, increase in experience as IT professional increased the incidence of professional stress. High stress observed among employees with more years of experience can be due to more responsibility. Now, new employees are given better training and are introduced to the profession in a phased manner which might help them to adjust and cope with the profession better. Hence the results in our study might be affected showing lower stress levels among younger employees compared to their senior counterparts who were not introduced into the profession as the current new employees.[17]

Screening tool used in our study to identify those at risk for developing depression found out that 43.4% of the study sample were at risk for developing depression. Various other studies have studied depression among IT professionals using other tools. One study done among Delhi software professionals reported that depression was present in 8% of their study sample by Zung rating scale and 6% by Hamilton scale.[16] A medium level of depression was reported in 84% of IT professionals in a study done on female IT professionals in Chennai.[17] The higher percentage of those who are at risk for developing depression in our study can be explained by the presence of higher percentage of subjects who were professionally stressed.

When statistical analysis was done to find the association between those who were professionally stressed and those at risk for developing depression, results showed 68.2% of those who were professionally stressed were at risk for developing depression compared with only 17.5% among those who were not professionally stessed. Using odds ratio, we found that those who were professionally stressed had 10 times higher risk of developing depression. Many studies have reported higher incidence of depression in those exposed to professional stress. In the study done on IT women professionals in chennai, it was found that depression was positively associated with overall stress of the professionals and also showed that overall stress found to have significant association with depression among employees.[17]

Etiological research has demonstrated a strong relationship between professional stressors and adverse health outcomes, notably cardiovascular disease and mental health disorders.[21,22] Use of computers has been observed to result in physical and mental health problems such as blood pressure and mood disturbance. The usual observed effects of the stress caused by human computer interaction at the workplace are increased physiological arousal, somatic complaints, mood disturbances, anxiety, fear, anger, and diminished quality of working life.[23,24] The relationship between stressful life events and development of mood disorders in vulnerable subjects has long been established.[25–27] As suggested by animal and human studies, biological mechanisms explaining stress leading to depression involve the dysregulation of stress hormones, i.e., glucocorticoids.[28] Persistently-elevated stress hormone levels may have direct neurotoxic effects on the brain, particularly in the hippocampus and can induce down-regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor, which impairs affect regulation.[29–31] Neurotrophic and Neuroplasticty hypothesis implicate stress as the major etiological factor in causing depression.[32,33] The interaction between stress and the molecular, cellular, and behavioural changes that attend the development of depression like state are becoming increasingly similar. Increasing appreciation of the effects of stress on the mechanisms of neuroplasticity clears that there is an intimate relationship between the stress, the mechanisms of neuroplasticity, and the pathophysiology of depression.[34,35] Psychological mechanisms include feelings of helplessness, which may result from individuals’ perceived inability to influence their stressful and uncomfortable working conditions.[36] Behavioural mechanisms linking work stress to poor mental health might include an inability to engage in leisure activities and to maintain strong social networks.[37] All the various explanations point out that stress significantly increases risk of developing depression by adversely influencing the human body in many ways. Our study finding that professionally stressed IT professioanls at 10 times higher risk for developing depression can thus be understood in the light of the above research findings.

In our study females were at higher risk for depression. Studies have found that work family conflict (i.e., work interference with family or family interference with work) is experienced more often by women than by men. Depression is found to be one of the most consistent and strongest outcome of work family confict.[38–41] In the Indian context with women being expected to handle household responsibilities as primary responsibility, women software engineers might experience more work family conflict increasing the prevalence of risk for developing depression women population.

In our study, subjects who were professionally stressed had 5.9 times higher prevalence of harmful alcohol use compared to those who were not professionally stressed. We did not come across any published data done on IT professionals associating professional stress and harmful alcohol use during our literture research. Many other studies done on other professionals have found that professioanl stress increases the risk of harmful alcohol consumption. Using longitudinal data, Crum and colleagues reported that men holding jobs that were high in demands and low in job control were more likely to develop either an alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence disorder than were men in jobs that lacked one or both of these two job stressors.[42] Vasse and colleagues reported that high work demands and poor interpersonal relations with supervisors and coworkers were positively related to anxiety, which was positively related to average weekly alcohol consumption.[43] Grunberg and colleagues reported that work pressure predicted higher average daily alcohol consumption and problem drinking among people who reported that they typically drank to relax and forget problems than among people who did not drink for those reasons.[44] Simple cause effect model, mediation model, moderation model, moderated mediation model are among the various models described to explain stress leading to harmful alcohol use.

Also we found that subjects who were at risk for developing depression had 4.1 times higher prevalence of harmful alcohol use compared with those who were not at risk for developing depression. No available study was found on IT professionals associating risk for developing depression population and harmful alcohol use during our literture research. Many other studies have found significant relation between depression and harmful alcohol use in other population. Sherbourne found higher rates of current and lifetime alcohol abuse and/or dependence in patients with depression 6% and 19% respectively.[45] Grant found higher rates of current and lifetime alcohol problems in the patients with depression, 21% and 40% respectively, compared to those without depression, 7% and 16%.[46] Many models and theories have been put forth across various studies, depression is found to be consistently associated with a higher prevalence of harmful alcohol use.

Limitations of the study

It is a cross-sectional study

Only screening questionnaires were used

Stress can be due to many factors, in our study screening was performed only for professional stress

No other causal factors for stress and risk for depression were assessed

Since depression is multifactorial, we have not looked at other possible triggering factors other than Professional stress

Harmful alcohol use is not further differentiated into abuse and dependance.

CONCLUSION

This study is unique as three different factors i.e., professional stress in IT professionals, risk for developing depression and harmful alcohol use were screened and association among them were studied. Since our interview sample contains professionals from various companies from different cities, it can be considered that the study sample was representative of IT professionals from across India. Our study showed that 51.2% of the software engineers are professionally stressed and are at 10 times higher risk for developing depression. Among software engineers we found that harmful alcohol use was much higher in professionally stressed and in those at risk for developing depression compared with their counterparts. India being a forerunner in IT segment, its continuing growth largely depends on its employees’ mental and physical health. Such higher rates of professional stress, risk for developing depression and harmful alcohol use among software engineers could hinder the progress of IT development and also significantly increase the incidence of psychiatric disorders. Preventive strategies like training in stress management, frequent screening to identify professional stress and depression at the initial stages and addressing these issues adequately might help the IT professionals cope with their profession better without affecting their lifestyle and health.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Ranjit L, Mahespriya L. Study on job stress and quality of life of women software employees. Int J Res Soc Sci. 2012;2:2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jefferson A, Singer, Neale MS, Schwartz GE. The nuts and bolts of assessing occupational stress: A collaborative effort with labour. In: Murphy LR, Schoenborn TF, editors. Stress manangement in work settings. Washington DC: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 1987. pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke RJ. Work and non-work stressors and well-being among police officers: The role of coping. Anxiety Stress Coping. 1998;11:345–62. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sekine M, Chandola T, Martikainen P, Marmot M, Kagamimori S. Socioeconomic inequalities in physical and mental functioning of Japanese civil servants: Explanations from work and family characteristics. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:430–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontana D. Professional life stress scale adapted from Managing stress. The British Psychological Society and Routledge Ltd; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhury S, Sudarsanan S, Saldanha D, Pawar AA, Ryali VS, Srivastava K, et al. Handbook of psychiatric rating scales. 1st ed. Pune: Navjeevan printing press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elliott TR, Frank RG. Depression following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:816–23. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babor TF, Biddle-Higgins JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gefen D, Straub D. Gender differences in perception and adoption of E-mail: An extension to the technology acceptance model. Vol. 21. MIS Quarterly; 1997. pp. 389–400. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tannen D. You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation. New York: Ballantine Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheinin R. Women as scientists: Their rights and obligations. J Bus Ethics. 1989;8:131–55. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konrad AM, Cannings K. The effects of gender role congruence and statistical discrimination on managerial advancement. Hum Relations. 1997;50:1305–28. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ragins BR, Sundstrom E. Gender and power in organizations: A longitudinal perspective. Psychological Bull. 1989;105:51–88. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sivaraman G, Mahalakshmy T, Kalaiselvan G. Occupation related health hazards: Online survey among software engineers of South India. Indian J Med Spec. 2011;2:77–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma AK, Khera S, Khandekar J. Computer related health problems among information technology professionals in Delhi. [Last accessed on 2012 May 12];Indian J Community Med. 2006 31:36–8. Available from: http://www.ijcm.org.in/text.asp?2006/31/1/36/54936 . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vimala B, Madhavi C. A study on stress and depression experienced by women IT professionals in Chennai, India. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2009;2:81–91. doi: 10.2147/prbm.s6049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajeswari KS, Anantharaman RN. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 2003. [Last accessed on 2012 May 12]. Development of an instrument to measure stress among software professionals: Factor analytic study, in Proceedings of ACM-SIGCPR Conference. Available from: http://www.portal.acm.org . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thong JY, Yap CS. Information systems and occupational stress: A theoretical framework. [Last accessed on 2012 May 14];Omega. 2000 28(6):681–92. Obtained from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0305-0483(00)00020-7 . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rashidi Z, Jalbani AA. Job Stress among Software Professionals in Pakistan: A Factor analytic Study. J Independent Stud Res (MSSE) 2009;7:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, Kouvonen A, Väänänen A, Vahtera J. Work stress in the etiology of coronary heart disease – A meta-analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:431–42. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stansfeld S, Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health – A meta-analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:443–62. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khosrowpour M, Culpan O. The impact of management support and education: Easing the causality between change and stress in computing environments. J Edu Syst. 1989;18:53–67. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith MJ, Conway FT, Karsh BT. Occupational stress in human computer interaction. Ind Health. 1999;37:157–73. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.37.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:837–41. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson SL. Life events in bipolar disorder: Towards more specific models. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:1008–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melchior M, Caspi A, Milne BJ, Danese A, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. Work stress precipitates depression and anxiety in young, working women and men. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1119–29. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Kloet ER, Joëls M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: From adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:63–75. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sapolsky RM, Krey LC, McEwen BS. The neuroendocrinology of stress and aging: The glucocorticoid cascade hypothesis. Endocr Rev. 1986;7:284–301. doi: 10.1210/edrv-7-3-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avitsur R, Stark JL, Sheridan JF. Social stress induces glucocorticoid resistance in subordinate animals. Horm Behav. 2001;39:247–57. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pariante CM, Miller AH. Glucocorticoid receptors in major depression: Relevance to pathophysiology and treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:391–404. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duman RS, Heninger GR, Nestler EJ. A molecular and cellular theory of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:597–606. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830190015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pittenger C, Duman RS. Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: A convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:88–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shors TJ, Seib TB, Levine S, Thompson RF. Inescapable versus escapable shock modulates long-term potentiation in the rat hippocampus. Science. 1989;244:224–6. doi: 10.1126/science.2704997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McEwen BS. Stress and hippocampal plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:105–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abramson LY, Seligman ME, Teasdale JD. Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. J Abnorm Psychol. 1978;87:49–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berkman LF, Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support and health. In: Berkman L, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellavia GM, Frone MR. Work-family conflict. In: Barking J, Kelloway EK, Frone MR, editors. Handbook of Work Stress. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2005. pp. 113–47. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. J Appl Psychol. 1992;77:65–78. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Netmeyer RG, Boles JS, McMurrian R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81:400–10. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eby LT, Casper WJ, Lockwood A, Bordeaux C, Brinley A. Work and family research in IO/OB: Content analysis and review of literature. J Vocat Behav. 2005;66:124–97. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crum RM, Muntaner C, Eaton WW, Anthony JC. Occupational stress and the risk of alcohol abuse and dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:647–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vasse RM, Nijhuis FJ, Kok G. Associations between work stress, alcohol consumption and sickness absence. Addiction. 1998;93:231–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9322317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grunberg L, Moore S, Anderson-Connolly R, Greenberg E. Work stress and self-reported alcohol use: The moderating role of escapist reasons for drinking. J Occup Health Psychol. 1999;4:29–36. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.4.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Wells KB, Rogers W, Burnam MA. Prevalence of comorbid alcohol disorder and consumption in medically ill and depressed patients. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2:1142–50. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.11.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant BF, Harford TC. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and major depression: Results of a national survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]