Abstract

Background:

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a very common gastrointestinal dysfunction. Despite strong evidence of high prevalence of depression and anxiety in IBS there is very limited research on this in India.

Materials and Methods:

Cases of IBS and controls with non-ulcerative dyspepsia were recruited from a gastroenterology clinic in Mumbai, India. Presence of anxiety disorder and depression were assessed by using the Hamilton Anxiety rating scale and Hamilton Depression rating scale respectively. Prevalence rates of anxiety and depression were established and Odds Ratio (OR) was calculated to determine the association of depression and anxiety disorders with IBS.

Results:

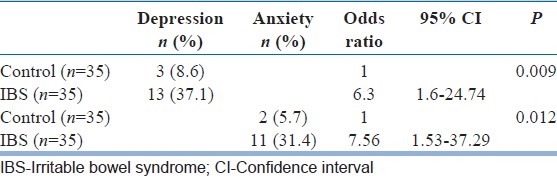

In IBS cases, the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorder was 37.1% and 31.4% respectively. In patients with IBS the OR for depression was 6.3 (95% CI 1.6-24.74, P=0.009) and the OR for anxiety disorder was 7.56 (95% CI 1.53-37.29, P=0.01).

Conclusion:

The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorder in IBS is very high. Therefore, screening of IBS patients for anxiety and depression would facilitate better interventions and consequently better outcomes.

Keywords: Anxiety, depression, irritable bowel syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a chronic, continuous or intermittent illness characterized by frequent and unexplained symptoms that include abdominal pain, bloating and bowel disturbance.[1] It is considered to be the most common gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction[2,3] with an estimated prevalence of 8-22% in general population.[3–5] It places a heavy burden on health services and accounts for 20-50% of referrals to gastroenterology clinics.[6–8] Though a number of biological triggers have been proposed for onset of IBS,[9–11] it has also been suggested that psychological factors, particularly those associated with the process of somatization play an important role and may even act as markers of IBS onset.[12] Recent studies have shown that subjects with IBS have higher levels of depression, anxiety and neuroticism as compared to those without IBS.[13,14] Various studies have shown that as many as 30-40% of patient with IBS have co-morbid depression or anxiety disorder.[15,16] It has also been reported that patients who come to medical attention tend to have a greater number of symptoms[17] and are more anxious and depressed.[18]

However, most of the evidence on IBS and co-morbid depression or anxiety disorder comes from western studies. There is very little research looking into the prevalence of these psychiatric disorders in patients with IBS in a developing country like India. Given the fact that there are significant socio-cultural differences, it is difficult to generalize research findings from developed countries. It therefore, warrants a need to undertake basic research in a developing country like India.

Thus, the aim of this study was to strengthen the limited evidence base by identifying the prevalence of common mental disorders such as depression and anxiety in patients with IBS in an Indian population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The sample for this research was selected from the patients attending the gastroenterology out-patient clinic at a government hospital in Mumbai, a metropolitan city of India. Thirty-five patients diagnosed with IBS using Rome's II diagnostic criteria[19] were randomly selected as cases. Another 35 patients diagnosed with non-ulcerative dyspepsia (NUD) from the same clinic were randomly selected as the control group. The only inclusion criterion was that all respondents selected were between the ages of 15 and 65 years.

All the selected patients underwent a brief interview for socio-demographic details such as age, gender, employment, education, marital status and socioeconomic status. For the purpose of this analysis, we converted age into a binary variable with a cut-off age of 35 years. Employment status was coded as a binary variable, with those who were currently employed were coded as economically active. Education status was also coded as a binary variable with respondents who were able to read or write were coded as literate. Marital status too was coded as a binary variable with two categories; married and single/post marital (divorced, separated, or widowed). Socio-economic status was determined using the Kuppuswamy's classification. This classification was developed for use in India and has been used extensively in hospital and community based research in India.[20,21] This scale takes account of education, occupation and income of the family to classify study groups in to high, middle and low socio-economic status. For our analyses we converted this polychotomous outcome variable into a binary outcome; low socio-economic status and middle/high socio-economic status. Presence of depression was diagnosed using the Hamilton depression rating scale[22] and anxiety disorder was diagnosed using the Hamilton Anxiety rating scale[23] respectively. These rating scales have been used in previous research studies in India.[24]

Analysis

Prevalence of depression and anxiety disorder was calculated for the IBS and control groups. Comparisons were made initially between the socio-demographic characteristics of IBS and control groups using Chi-square tests. In order to determine the independent associations between IBS and depression/anxiety disorders, odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals were calculated. The threshold for statistical significance was set at the standard P value of 0.05.

RESULTS

In total there were 35 respondents with IBS and 35 controls. The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorder in IBS was 37.1% and 31.4% respectively. The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorder in the control group was 8.6% and 5.7% respectively.

Table 1 describes the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents with and without IBS. Compared to the controls, a higher proportion of respondents with IBS were female (45.7% vs. 42.9%), older than 35 years (37.1% vs. 28.6%) and economically inactive (28.6% vs. 17.1%). A significantly higher proportion of respondents with IBS were illiterate (11.4% vs. 0%), single or post-marital (37.1% vs. 11.4%) and were from a lower socio-economic strata (57.1% vs. 25.7%).

Table 1.

Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with irritable bowel syndrome

The OR for depression in respondents with IBS was 6.3 (95% CI 1.6-24.74, P=0.009). The OR for anxiety disorders in respondents with IBS was 7.56 (95% CI 1.53-37.29, P=0.01)

DISCUSSION

Previous studies from developed countries have reported similar high prevalence rates of anxiety and depression in IBS.[13,14] This prevalence of depression or anxiety in IBS is higher than in primary care (16% depression, 24% mixed anxiety depression) population in India[25] and other developing countries (6.2% depression-25% anxiety).[26–28] In a previous study, IBS patients showed an overall higher degree of psychological symptoms in general[29] and anxiety symptoms in particular.[30] In one study the mean scores on Symptom Checking List questionnaire-90 (SCL90) for depression and anxiety in diarrhea predominant IBS (1.1 and 1.0), constipation predominant IBS (1.6 and 1.3), and alternating IBS (1.5 and 1.2) subtypes were higher than in healthy controls (0.4 and 0.4).[29] On the other hand, in a study comparing IBS, Inflammatory bowel disease and chronic hepatitis C (HCV) there was no significant difference between groups in the prevalence of anxiety but IBS group had a statistically significant lower prevalence of depression compared to HCV (15% vs. 34%).[31]

Our findings of a high proportion of respondents with IBS (45.7%) than controls (42.9%) being female has also been reported in a previous studies.[31,32] In the same studies IBS respondents were significantly older than those with HCV (Mean age 54 vs. 45) which is in accordance with our findings; although in our study this age effect is not statistically significant. The high proportion of economically inactive IBS respondents in our study is in accordance with previous studies which have reported that people with IBS are more likely to be unable to work.[33] Similar to our study findings, Wilson et al. reported a higher risk of IBS in the more deprived but did not report any significant effect of level of education on prevalence of IBS.[34]

Although our study has a relatively modest sample size, these are fairly severe cases that were either referred or self-presented to the gastroenterology clinic. Another shortcoming of our study is its cross-sectional design, which does not allow us to determine direction of causality in the relationship between IBS and depression/anxiety. In order to clarify the temporal relationship prospective studies with a bigger sample size are essential in the future. As far as we are aware, this is a first of its kind study in India. Furthermore, we have used standardized and validated rating scales to make a diagnosis of anxiety and depression.

The findings of our study can be summarized as follows: (1) IBS is significantly associated with lower education, low socio-economic status and being single or post-marital, (2) Almost a third of the patients with IBS had depression or anxiety disorders, and (3) There is an increased risk of depression and anxiety disorders in IBS as compared to the controls with NUD.

IBS accounts for a huge proportion of referrals to gastroenterology clinics and the cost associated with IBS to an individual and to the society are substantial. Psychological disorders comorbid with IBS adds to their disability as well as cost to the individual and the society. Thus, the high prevalence of anxiety and depression in IBS in our study supports a case for screening for these disorders in GI clinics. Furthermore, recognition and treatment of these co-morbidities could improve patient outcomes. Future studies should focus on replicating or refuting these findings in larger samples as well as in testing interventions aimed at targeting psychological morbidities in this patient group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Dr. R. M. Haridas (HOD, Department of Psychiatry, Sir J.J. Group of Hospitals, Mumbai) for his valuable guidance. I would also like to thank the Department of Gastro-Enterology, Sir J.J. Group of Hospitals, Byculla, Mumbai for allowing me access to the patients in their out-patient department.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Corney RH, Stanton R. Physical symptom severity, psychological and social dysfunction in a series of outpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1990;34:483–91. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90022-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Van Dyke C, Melton LJ., 3rd Epidemiology of colonic symptoms and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:927–34. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90717-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones R, Lydeard S. Irritable bowel syndrome in the general population. BMJ. 1992;304:87–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6819.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saito YA, Locke GR, Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Fett SL, Melton LJ., 3rd A comparison of the Rome and Manning criteria for case identification in epidemiological investigations of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2816–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Onset and disappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:165–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvey RF, Salih SY, Read AE. Organic and functional disorders in 2000 gastroenterology outpatients. Lancet. 1983;1:632–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson A, Sircus W, Eastwood MA. Frequency of “functional” gastrointestinal disorders. Lancet. 1977;2:613–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91466-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fielding JF. A year in out-patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Ir J Med Sci. 1977;146:162–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03030953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malinen E, Rinttilä T, Kajander K, Mättö J, Kassinen A, Krogius L, et al. Analysis of the fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy controls with real-time PCR. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:373–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neal KR, Hebden J, Spiller R. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms six months after bacterial gastroenteritis and risk factors for development of the irritable bowel syndrome: Postal survey of patients. BMJ. 1997;314:779–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7083.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Si JM, Yu YC, Fan YJ, Chen SJ. Intestinal microecology and quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1802–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i12.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinman A, Kleinman J. Somatisation: The interconnectedness in Chinese society among culture, depressive experiences and meaning of pain. In: Kleinman A, editor. Culture and Depression. Studies in the Anthropology of Cross Culture Psychiatry of Affect and Disorder. London: University of California Press; 1985. pp. 429–90. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. Epidemiology and health care seeking in the functional GI disorders: A population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2290–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locke GR, 3rd, Weaver AL, Melton LJ, 3rd, Talley NJ. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: A population based nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:350–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lydiard RB, Falsetti SA. Experience with anxiety and depression treatment studies: Implications for designing irritable bowel syndrome clinical trials. Am J Med. 1999;107:65S–73. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tollefson GD, Tollefson SL, Pederson M, Luxenberg M, Dunsmore G. Comorbid irritable bowel syndrome in patients with generalized anxiety and major depression. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1991;3:215–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heaton KW, O’Donnell LJ, Braddon FE, Mountford RA, Hughes AO, Cripps PJ. Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a British urban community: Consulters and non-consulters. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1962–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masand PS, Kaplan DS, Gupta S, Bhandary AN, Nasra GS, Kline MD, et al. Major depression and irritable bowel syndrome: Is there a relationship? J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56:363–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE. Rome II: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2nd ed. McLean: Degnon Associates; 2000. p. 670. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuppuswami B. Manual of socioeconomic scale (Urban) New Delhi: Manasayan; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishra D, Singh HP. Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic status scale – A revision. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:273–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02725598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaudhury PK, Deka K, Chetia D. Disability associated with mental disorders. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:95–101. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel V, Pereira J, Coutinho L, Fernandes R, Fernandes J, Mann A. Poverty, psychological disorder and disability in primary care attenders in Goa, India. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:533–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.6.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lima MS, Beria JU, Tomasi E, Conceicao AT, Mari JJ. Stressful life events and minor psychiatric disorders: An estimate of the population attributable fraction in a Brazilian community-based study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1996;26:211–22. doi: 10.2190/W4U4-TCTX-164J-KMAB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Araya R, Rojas G, Fritsch R, Acuña J, Lewis G. Common mental disorders in Santiago, Chile: Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:228–33. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollifield M, Katon W, Spain D, Pule L. Anxiety and depression in a village in Lesotho, Africa: A comparison with the United States. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:343–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eriksson EM, Andrén KI, Eriksson HT, Kurlberg GK. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes differ in body awareness, psychological symptoms and biochemical stress markers. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4889–96. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halder SL, McBeth J, Silman AJ, Thompson DG, Macfarlane GJ. Psychosocial risk factors for the onset of abdominal pain.Results from a large prospective population-based study. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1219–25. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Andrews JM, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Harley HA, et al. Psychological problems in gastroenterology outpatients: A South Australian experience. Psychological co-morbidity in IBD, IBS and hepatitis C. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2008;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang A, Liao X, Xiong L, Peng S, Xiao Y, Liu S, et al. The clinical overlap between functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome based on Rome III criteria. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, Temple RD, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, et al. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson S, Roberts L, Roalfe A, Bridge P, Singh S. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: A community survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:495–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]