Introduction

Osteonecrosis may occur in major joints, including the hips, knees, shoulders, and wrists. In most cases, we believe it is caused by a combination of mechanical and circulatory etiologies, which ultimately result in the loss of blood supply to the bone [1]. Necrosis usually occurs unilaterally and affects one joint, although bilateral, multisite occurrence of this condition has been described [2]. Kienbock’s disease—avascular necrosis of the lunate—most commonly occurs unilaterally and its pathogenesis and therefore appropriate method of treatment remains unclear. In this report, we describe a patient with concurrent bilateral Kienbock’s disease, Perthes disease, and transient ischemic attack (TIA). We suggest that in this case the bilateral Kienbock’s disease stems from a patient-related pathological tendency rather than from mechanical overload on the joints alone.

Case Report

A 49-year-old left hand-dominant male laborer presented with increasing pain in his left wrist. There was no history of remote or recent trauma. The patient denied any symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Past medical history and review of systems was positive for moderately severe TIAs 10 years prior. He had been diagnosed with bilateral Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease as a child and bilateral Kienbock’s disease that first appeared in the nondominant (right) hand at age 39. He was treated initially with an unclear partial wrist fusion that included the capitate, scaphoid, and perhaps the scaphotrapezialtrapezoidal joint at that time, but following failure of the procedure, was converted to a successful total wrist fusion on the right 5 years later. The patient is not known to have a seizure disorder and did not appear to have had a seizure that could have explained the TIAs. He does not suffer from diabetes and initial blood electrolytes were all within normal limits. He also had a coagulation work up that included a profile of international normalized ratio, partial thromboplastin time, platelets and fibrinogen that was within normal limits. Work up for other background diseases such as steroid use, vasculopathies including a rheumatological evaluation for inflammatory disease, and alcohol abuse was negative.

On examination, the patient was neurologically intact. Physical examination of his left wrist revealed no obvious swelling and only slight tenderness to palpation over the mid part of the dorsum of the wrist (over the lunate). Active extension of the left wrist was 25° with 17° of flexion. He had full pronation and supination. Motion could not be compared to the right wrist which was fused. Wrist pain on a scale of 0–10 was 8 during rest and 10 after wrist activity. Grip strength was immeasurable (the patient could not hold on to the grip meter without pain) and the disabilities of arm and shoulder (DASH) score was 100.

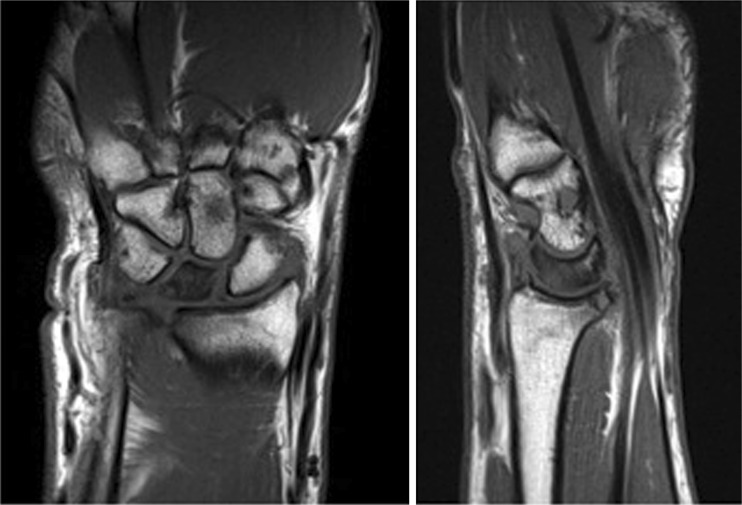

Radiographs demonstrated increased density of the left lunate with mild collapse. MRI of the left wrist demonstrated diffuse T1 hypointensity with corresponding T2 hyperintensity within the lunate consistent with avascular necrosis (Fig. 1). Because of the previous right wrist arthrodesis and his young age, concerns were raised that immobilization of the wrist would prevent the patient from carrying on his independent lifestyle. He therefore underwent a trial course of hand therapy. This failed and a decision was made to perform a capitate osteotomy. A partial capitate osteotomy was performed as described by Moritomo et al. [6]. The patient did very well with significant pain relief. He was measured for range of motion and grip strength at 3 months postsurgery. Range of motion measured 20° of extension and 50° of flexion. His grip strength (average of three measurements) was 30 lbs in the operated hand and 75 lbs in the fused wrist. We expect these measurements to improve with time and he is still in follow up.

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patient’s wrist showing a hypo-intense lunate bone on the T1-weighted views

Discussion

The etiology of osteonecrosis in general remains controversial. Robert Kienböck reasoned that the disorder results from an initial injury that causes tears to the ligaments and blood vessels, thus limiting or impairing blood supply to the bone; however, a well-defined acute traumatic event is rarely documented [3]. Whether repetitive trauma disrupts the arterial blood supply to the lunate causes subcortical microfractures that result in osteonecrosis or causes venous congestion that leads to arterial insufficiency is unknown. Although the extraosseous blood supply is abundant, theoretically the intraosseous circulation may be vulnerable [4].

The patient in our case is not typical of Kienbock’s disease in his bilateral presentation of osteonecrosis. Bilateral Perthes is also relatively rare, occurring in only 8–24 % of cases [5]. The case described here, because of the many areas involved, suggests that osteonecrosis could be explained by a patient related pathology rather than a traumatic event or mechanical overload alone. Though there was no evidence that the patient suffered from any vascular pathology or inflammatory disease, the patient’s history of TIAs and multisite avascular osteonecroses can all be tied to a microvessel etiology that may increase the patient’s tendency to distal ischemia. It is possible that this tendency would not be detected on standard evaluation and testing. Although we may assume that osteonecrosis occurred in the particular joints—wrist and hip—due to mechanical overload in those particular regions, perhaps due to the patient’s occupation as a heavy laborer, this condition may have been compounded by an underlying anatomical or vascular condition. Similar descriptions of bilateral and multifocal disease have been described but all had documented background pathology. Steinhauser et al. found that certain constitutional factors play a decisive role in the pathogenesis of Kienbock’s disease, especially in the bilateral cases [7]. Kahn described a case of bilateral lunate osteonecrosis associated with osteomyelitis [5]. Mok et al. described bilateral Kienbock’s disease in association with systemic lupus erythematosus where vasculitis related to the antiphospholipid antibodies was thought to be responsible [9]. Similarly, Rennie et al. described bilateral disease associated with Reynaud’s disease and scleroderma [8]. It is interesting to note that certain bones tend to develop avascular necrosis in the presence of vasculitis, due perhaps to their intraosseous anatomy, their specific mechanical load patterns, or a combination of both.

A multitude of surgical treatments have been prescribed for the treatment of Kienbock’s disease. These include lengthening the ulna, shortening the radius, excision of the lunate, proximal-row carpectomy, silicone replacement arthroplasty, excisional arthroplasty with a tendon implant, various arthrodeses of the surrounding carpal bones, revascularization procedures, total wrist arthrodesis, and total wrist arthroplasty. Since the origins of the disease remain unclear, no universal effective course of treatment exists. Perhaps in cases of bilateral Kienbock’s disease, we can assume that the pathophysiology at least partially consists of a background problem, and treat these cases differently, including treatment of the underlying vasculitis and vasculopathies, but only if, and when these can be identified.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest, commercial associations, or intent of financial gain regarding this research.

References

- 1.Beredjiklian PK. Kienbock’s disease. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(1):167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelberman RH, Gross MS. The vascularity of the wrist. Identification of arterial patterns at risk. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;202:40–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn ML, Bade HA. Lunate osteomyelitis in a patient with bilateral Kienbock’s disease. Orthop Rev. 1986;15(8):521–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kienbock R. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1947;59(33):546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mok CC, Lau CS, Cheng PW, Ip WY. Bilateral Kienbock’s disease in SLE. Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26(6):485–487. doi: 10.3109/03009749709065726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moritomo H, Murase T, Yoshikawa H. Operative technique of a new decompression procedure for Kienbock disease: partial capitate shortening. Tech Hand Upper Extrem Surg. 2004;8(2):110–115. doi: 10.1097/01.bth.0000126571.20944.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rennie C, Britton J, Prouse P. Bilateral avascular necrosis of the lunate in a patient with severe raynaud’s phenomenon and scleroderma. J Clin Rheumatol. 1999;5(3):165–168. doi: 10.1097/00124743-199906000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinhauser J, Posival H. Bilateral necrosis of the lunate bone. A pathogenic study. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1982;120(2):151–157. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1051593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroh DA, LaPorte DM, Marker DA, Johnson AJ, Mont MA. Atraumatic osteonecrosis of the distal radius and ulna: case series and review. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(1):134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]