Abstract

We report the effects of intravitreal ranibizumab as salvage therapy in an extremely low–birth-weight (ELBW) infant with rush type retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). This case was a girl of 23 weeks gestational age weighing 480 g at birth. At a postconceptual age of 33 weeks, she presented with zone 1, stage 3 ROP with plus disease. Despite intravitreal bevazucimab and laser photocoagulation, extraretinal fibrovascular proliferation persisted. Intravitreal 0.25 mg (0.025 ml) ranibizumab was injected OU. After treatment, extraretinal fibrovascular proliferation disappeared. Fundus examination showed flat retinas and normal vasculature in both eyes. She has been followed up for 2 years. Intravitreal ranibizumab injection seems effective and well tolerated as salvage therapy in an ELBW infant with rush type ROP. No short-term ocular or systemic side effects were identified. More cases and longer follow-up are mandatory.

Keywords: Extremely low-birth-weight, intravitreal ranibizumab, rush type retinopathy of prematurity

Introduction

Extremely low–birth-weight (ELBW) infant is defined as a baby with birth weight of less than 1 000 g.[1] Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a disease of the premature infant retina that has not yet fully vascularized. In late stages, neovascularization (NV) occurs and is mainly attributable to the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Highly elevated VEGF in vitreous fluid has been proved in patients with ROP.[2] Ranibizumab (Lucentis®, Genentech Inc., South San Francisco, CA) is an antibody fragment of humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody. The results below elucidate the benefits of intravitreal ranibizumab as salvage therapy in an ELBW infant with rush type ROP.

Case Report

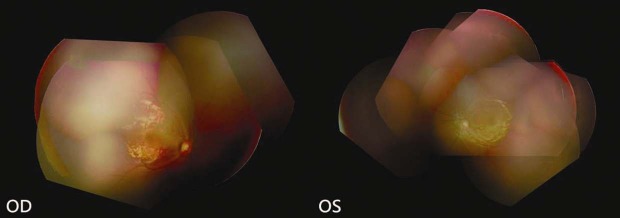

This patient was a female infant with a birth weight of 480 g at a gestational age of 23 weeks. Fundus examination of our patient began at a postconceptual age (PCA) of 31 weeks. Tunica vasculosa lentis, yellowish-grey color of the general fundus along with attenuation of the vessels were noted. A satisfactory view of the peripheral retina could not be obtained. At a PCA of 33 weeks, she presented with zone 1, stage 3, ROP with plus disease OU. She was treated with intravitreal 0.625 mg (0.025 ml) bevacizumab (Avastin; Genentech Inc., South San Francisco, CA) injection and NV regressed for 2 months. However, zone 1, stage 3, ROP with plus disease recurred at a PCA of 44 weeks. Dense laser photocoagulation with a laser indirect ophthalmoscope (IRIDEX®, OcuLight SL/SLx Infrared 810 nm laser) was performed to treat the peripheral avascular retina. One month after the laser treatment, the NV persisted with no tractional retinal detachment. Informed consent was obtained from the infant's parents, and intravitreal 0.25 mg (0.025 ml) ranibizumab injection was administered under topical anesthesia. About one month after the injection, fundus examination revealed flat retinas without extraretinal fibrovascular proliferation. Previous laser spots could be identified around the retinal periphery [Figure 1]. Normal vascularization toward the peripheral retina developed.

Figure 1.

Fundus examination after intravitreal ranibizumab injection revealed flat retinas without extraretinal fibrovascular proliferation and normal vascularization toward the peripheral retina in both eyes. Previous laser spots could be identified around the periphery of the retina

In June 2012, fundus examination of the 2-year-old patient revealed flat retina and normal vasculature. The axial length was 19.66 OD and 19.55 mm OS.

Discussion

Risk factors for severe ROP include prematurity, oxygen exposure, respiratory distress syndrome, patent ductus arteriosus, and meningitis. All ELBW infants should undergo an eye examination by an experienced pediatric ophthalmologist at a chronological age of 4 weeks (or at a PCA of 31 weeks, if the infant is born prior to 27 weeks of gestation). Depending on the results, the infant should be re-examined at a minimum of every 2 weeks until the retina is fully vascularized.

The VEGF level in vitreous fluid is highly elevated in patients with ROP.[2] NV is mainly attributable to the expression of VEGF. Treatment with an anti-VEGF agent, such as bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech/Roche), seems effective and well-tolerated in the majority of ROP cases, especially in stage 3 ROP.[3] Favorable results were also seen in a randomized, prospective study with a concurrent control group.[4] In the literature, the doses of bevacizumab used for severe ROP ranged from 0.4 to 1.25 mg, with 0.625 mg being the most common.[3,4] This led us to select 0.625 mg as the dose of bevacizumab. Nevertheless, a long-term study is necessary to clarify whether long-term ocular or systemic side effects of bevacizumab can occur.

A number of potential complications related to intravitreal anti-VEGF injection can occur in a pediatric patient. Infants may be more vulnerable to VEGF blockade than adults are. The procedure can cause infection and trauma. The full effect of anti-VEGF on normal developing vessels is not well understood. Systemic adverse effects of the anti-VEGF antibody are also a concern.

After the intravitreal injection, the serum concentration of bevacizumab is greater than that of ranibizumab.[5,6] In addition, ranibizumab has several safety-related advantages, including a shorter systemic half-life and the antibodies lack a crystallizable fragment.[7] In theory, the risk of systemic adverse events and complement-mediated toxicity is reduced by using ranibizumab.

Recent studies reveal that VEGF is not the only growth factor upregulated in the eye: insulin-like growth factor-1, angiopoietin-1, and angiopoietin-2 have also been identified.[8,9] Vascular growth factors show compensatory mechanisms in ROP. Thus, the inhibition of VEGF expression alone may be unable to induce regression in all ROP cases. Although most eyes respond well to intravitreal bevacizumab injection, 10% of stage 3 ROP eyes required additional laser treatment.[2]

Data regarding the complications associated with intravitreal injection of ranibizumab for zone 1 ROP with plus disease remain scarce. Only one case of delayed-onset retinal detachment after intravitreal ranibizumab injection for zone 1 ROP with plus disease has been reported.[10] Fundus photography and fluorescein angiography performed 3 months after laser photocoagulation and intravitreal injection of ranibizumab revealed regression of extraretinal fibrovascular proliferation, but incomplete normal vascularization toward the peripheral retina. In such cases, more frequent examinations are very important for timely intervention. In this case, the incomplete normal vascularization should not be attributed to intravitreal injection of ranibizumab.

In an ELBW infant, management of ROP, which can range from frequent examinations to intravitreal anti-VEGF injection, laser surgery, or even vitrectomy, is dictated by ROP stage and location. The presence of significant plus disease or tortuosity of the retinal vessels is a poor prognostic sign and requires immediate treatment. ELBW infants who do not have ROP, or in whom ROP has resolved, should undergo a follow-up eye examination at the age of 6 months or until complete vascularization toward the peripheral retina occurs.

Our patient was 23 weeks gestational age, weighing 480 g at birth. Despite intravitreal bevazucimab and laser photocoagulation, extraretinal fibrovascular proliferation persisted. Because the intraocular bevacizumab can significantly suppress systemic VEGF levels, we chose half dose of ranibizumab as salvage therapy. After intravitreal ranibizumab, extraretinal NV disappeared. Fundus examination showed normal vasculature to the periphery. At the age of 2 years, no ocular or systemic adverse effects have been noted. Intravitreal ranibizumab injection seems effective and well tolerated as salvage therapy in an ELBW infant with rush type ROP. More cases and longer follow-up are mandatory.

Footnotes

Source of Support: None

Conflict of Interest: No.

References

- 1.Hakansson S, Farooqi A, Holmgren P, Serenius F, Hogberg U. Proactive management promotes outcome in extremely preterm infants: A population-based comparison of two perinatal management strategies. Pediatrics. 2004;114:58–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato T, Kusaka S, Shimojo H, Fujikado T. Vitreous levels of erythropoietin and vascular endothelial growth factor in eyes with retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1599–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu WC, Yeh PT, Chen SN, Yang CM, Lai CC, Kuo HK. Effects and complications of bevacizumab use in patients with retinopathy of prematurity: A multicenter study in Taiwan. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:176–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mintz-Hittner HA, Kennedy KA, Chuang AZ BEAT-ROP Cooperative Group. Efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab for stage 3+ retinopathy of prematurity. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:603–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakri SJ, Snyder MR, Reid JM, Pulido JS, Singh RJ. Pharmacokinetics of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) Ophthalmology. 2007;114:855–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakri SJ, Snyder MR, Reid JM, Pulido JS, Ezzat MK, Singh RJ. Pharmacokinetics of intravitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis) Ophthalmology. 2007;11:2179–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaudreault J, Fei D, Rusit J, Suboc P, Shiu V. Preclinical pharmacokinetics of Ranibizumab (rhuFabV2) after a single intravitreal administration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:726–33. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiang N, Zhao MJ, Li XY, Zheng HH, Li GG, Li B. Redundant mechanisms for vascular growth factors in retinopathy of prematurity in vitro. Ophthalmic Res. 2011;45:92–101. doi: 10.1159/000316134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato T, Shima C, Kusaka S. Vitreous levels of angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 in eyes with retinopathy of prematurity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:353–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang SY, Choi KS, Lee SJ. Delayed-onset retinal detachment after an intravitreal injection of ranibizumab for zone 1 plus retinopathy of prematurity. J AAPOS. 2010;14:457–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]