Abstract

Dacryocystorhinostomy or DCR is one of the most common oculoplastics surgery performed. It is a bypass procedure that creates an anastomosis between the lacrimal sac and the nasal mucosa via a bony ostium. It may be performed through an external skin incision or intranasally with or without endoscopic visualization. This article will discuss the indications, goals, and simple techniques for a successful outcome of an external DCR.

Keywords: Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction, dacryocystorhinostomy, primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction, secondary acquired lacrimal duct obstruction

Introduction

Dacryocystorhinostomy or DCR is among the common oculoplastics surgeries performed for managing epiphora due to nasolacrimal duct obstruction.[1,2] It is a bypass procedure that creates an anastomosis between the lacrimal sac and the nasal mucosa via a bony ostium. It may be performed through an external skin incision or intranasally with or without endoscopic visualization. This article will discuss the indications, goals, and simple techniques for a successful outcome of DCR.

Goals of the surgery

There are two clear goals of DCR procedure. One is to make a large bony osteum into the nose and that remains so. Second is to have a mucosal lined anastomosis. Since both these purposes are well served by an external route, it is one of the preferred approaches with high success rates.

Clinical indications

Persistent congenital lacrimal duct obstructions unresponsive to previous therapies.

Congenital lacrimal duct obstructions associated with mucocele, dacryocystitis, and not responsive to other treatments.

Primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstructions (PANDO).[3]

Secondary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstructions (SALDO).[4]

Preoperative requisites

Confirmation of the diagnosis and clinical findings.

Hemoglobin levels.

Bleeding and clotting times.

Blood pressure measurement.

Random blood sugars.

Additional general anesthesia investigations when required.

Steps of the surgery

Anesthesia

The surgery can be done under general anesthesia or local anesthesia.[5] The latter is the most commonly employed modality. Local anesthesia is given by both infiltration as well as topical application. For infiltration 2% lignocaine with 0.5% Bupivacaine with or without adrenaline is used. Infratrochlear nerve that supplies the lacrimal apparatus is blocked first. The nondominant hand marks the supraorbital notch and the needle is inserted into the lateral edge of the medial third of the eyebrow and advanced to just medial to medial canthus and 2cc of the drug is injected. The tissues along the anterior lacrimal crest is infiltrated subcutaneously and the needle enters deeper at about 3 mm medial to medial canthus, and without withdrawing the needle the drug is injected into deeper tissues up to periosteum both superiorly and inferiorly. A drop of topical proparacaine is placed in conjunctival cul de sac for intraoperative comfort. Nasal mucosa is sprayed with 10% lignocaine 1-2 puffs followed by packing with 4% lignocaine and 0.5% xylometazoline. Alternatively topical lignocaine spray along with topical xylometazoline can be used without packing the nasal cavity. The forceps should guide the medicated cottonoid from the external nare superiorly and backwards so that it reaches the middle meatus, the site of osteum [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Preoperative nasal packing

Incision

Though various incisions have been described, the authors prefer the commonly used curvilinear incision of about 10-12 mm in length, 3-4 mm from the medial canthus along the anterior lacrimal crest [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

A typical curvilinear incision

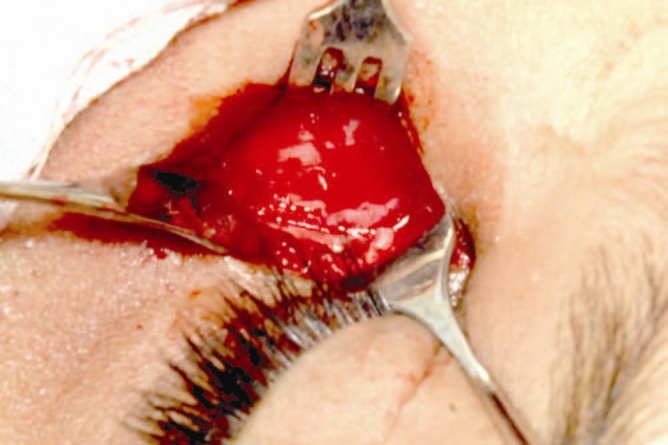

SAC dissection

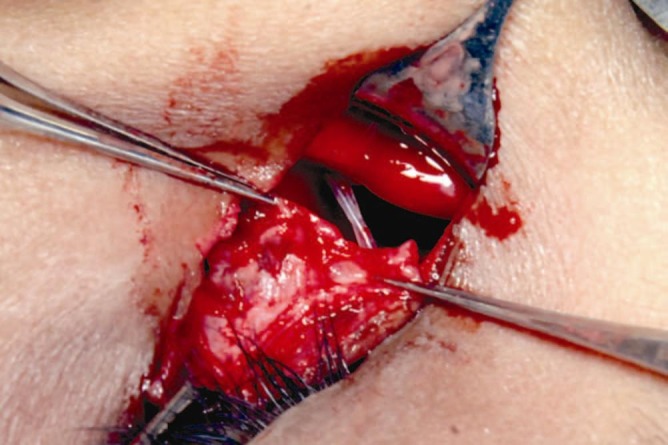

Blunt dissection is carried on to reach the periosteum. A freer's elevator is used to separate the periosteum from the bone and reflect it laterally along with the lacrimal sac to expose the lacrimal fossa. All efforts should be made to preserve the medial canthal tendon and dissected only when needed [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Sac dissected laterally to expose the bony lacrimal fossa

Bony ostium creation

Once the lacrimal fossa is exposed, bone punching should be started at the junction of lamina papyracea of the ethmoid and lacrimal bone. The kerrison bone punch should be gently inserted between the bone and the nasal mucosa and the ostium sequentially enlarged [Figures 4 and 5]. The extent of the ostium which the authors follow is

Figure 4.

Kerrison punch being used to create a bony osteum

Figure 5.

A large bony osteum exposing the nasal mucosa

Anteriorly till the punch cannot be inserted between the bone and the nasal mucosa.

Posteriorly till removal of aerated ethmoid.

Superiorly till 2 mm above the medial canthus.

Inferiorly till the nasolacrimal canal is partly deroofed.

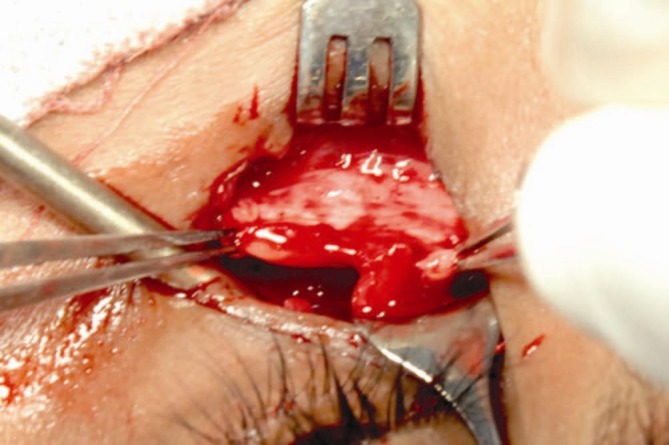

Flap formation

The first step is to create sac flaps. To do this, a bowman's probe is passed through the lower punctum and bent in such a way to tent the sac as posterior as possible to create a large anterior and small posterior flap. Alternatively fluorescein stained viscoelastic can be injected from the upper punctum to dilate the sac and help in creating flaps. Using the probe as guide, an “H”-shaped incision is made with the help of a number 11 or 15 blade right across the sac from the fundus to the nasolacrimal duct. Flaps are raised and the posterior one is cut [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Lacrimal sac incision being taken by an 11 number blade using the probe as a guide

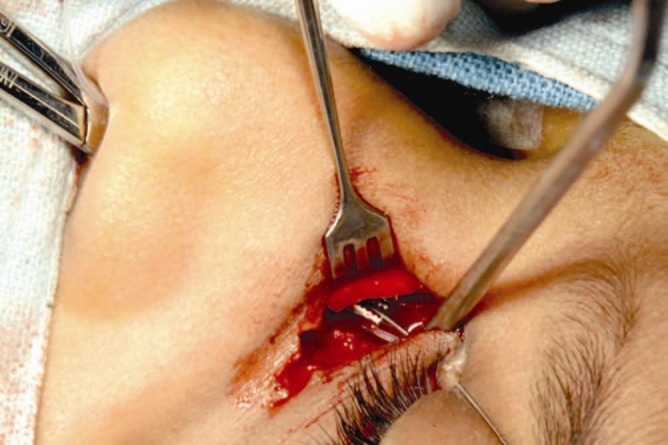

The second step is to fashion nasal mucosal flaps. With the help of number 11 blade incisions are made in the nasal mucosa along the bony ostium except anteriorly to have a hinged flap. The large anterior flap is raised and the posterior small residual flap is cut [Figure 7]. Alternatively both the flaps can be sutured but no significant difference in the success has been noted in doing this either way.[6,7]

Figure 7.

Raising a large nasal mucosal flap

Flap anastomosis

It is important to appose nasal mucosal and sac flap edge to edge. Excess nasal mucosa can be excised in a controlled manner so as to avoid sagging of the flaps that may compromise the tear drainage later [Figure 8]. In case of overriding, nasal mucosal overriding is preferable or alternatively one can tent the flaps and suture to the overlying orbicularis

Figure 8.

Taut flap anastomosis

Wound closure

Once flaps are secured, the orbicularis is sutured back with 6-0 vicryl followed by skin with 6-0 silk [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

Sutured surgical wound

Tips for hemostasis

Good preoperative assessment to rule out bleeding diathesis.

Preoperative blood pressure assessment.

Use of adrenaline along with local anesthetics provided there is no medical contraindication.

Good nasal packing right in the beginning if bleeding anticipated.

Raising the head end of the table.

Avoid known blood vessels.

Well powered suction.

Judicious use of cautery.

Keep materials like gel foam or bone wax in the armamentarium.

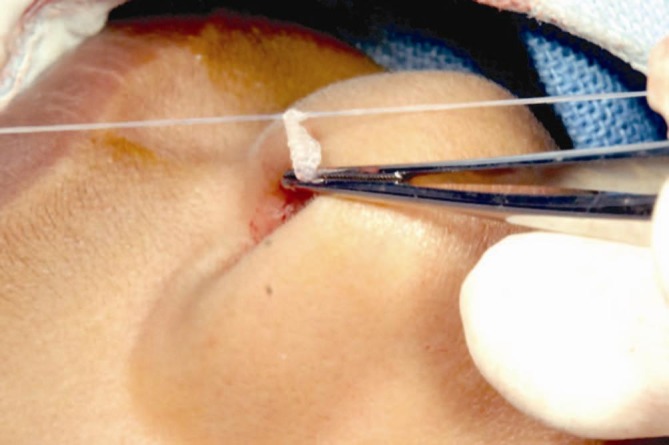

Adjunctive measures (use of mitomycin C and intubation)

Mitomycin C in a concentration of 0.04% is used if there are intra-sac synechiae, soft tissue scarring like in failed DCR's and in the presence of a complicated surgery. Intubation is also advisable for similar indications but in addition it is also used in the presence of canalicular problems and inadequate flaps[8] [Figures 10–12].

Figure 10.

Intubation: upper canaliculi intubated. The bodkins are being retrieved by a transnasal artery forceps

Figure 12.

Intubation: tubes being secured in the nose

Figure 11.

Intubation: tubes in place before flap anastomosis

Immediate postoperative steps

Once wound is closed, reassure the patient that the surgery went fine. Nasal packing is optional. When needed it is important to note that the purpose of this pack is for hemostasis only so deeper packing like preoperative one should be avoided for it risks damaging the flaps. The patient is started on oral antibiotics and analgesics.

Postoperative follow-ups

After the surgery patient is seen on the first postoperative day. The nasal pack if any is gently removed and hemostasis assessed. The wounds are cleaned with 5% betadine, and the patient is discharged on oral antibiotics and analgesics, topical antibiotics and steroids, nasal decongestants, and steroid nasal sprays. One week postoperative the sutures are removed, oral medications discontinued, topical steroids are tapered and nasal medications continued for two more weeks. The patient is reviewed at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months. If the patient is intubated then tube removal is usually done at 12 weeks.

Complications

Complications following DCR surgery can be divided as early (1-4 weeks), intermediate (1-3 months) and late (>3 months).[1–3]

Early complications include wound dehiscence [Figure 13], wound infection, tube displacement [Figure 14], excessive rhinostomy crusting [Figure 15], and intranasal synechiae.

Figure 13.

Early wound dehiscence following an external DCR

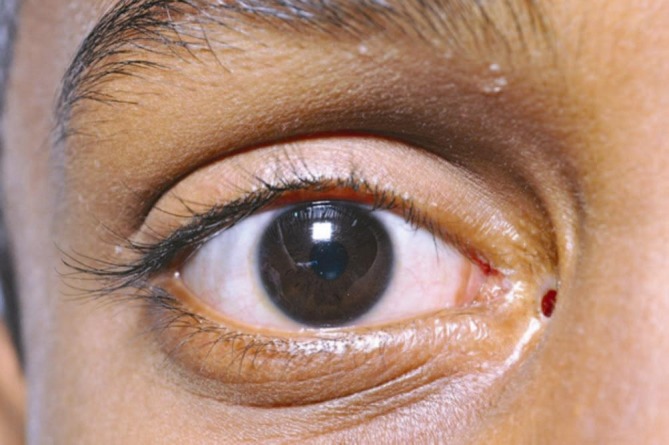

Figure 14.

An example of stent prolapse

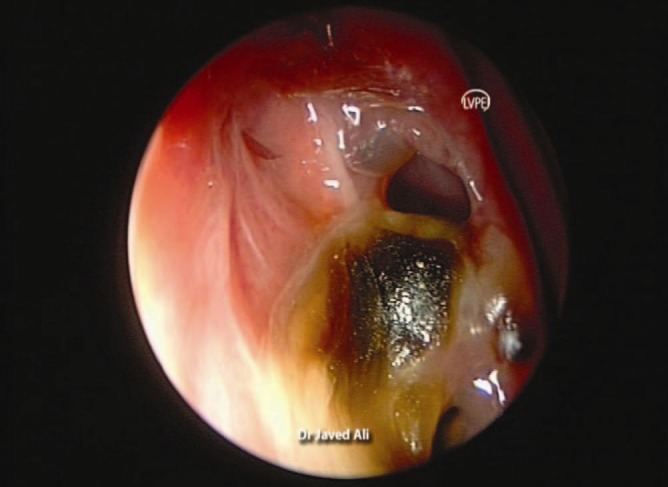

Figure 15.

Endoscopic view of rhinostomy scarring

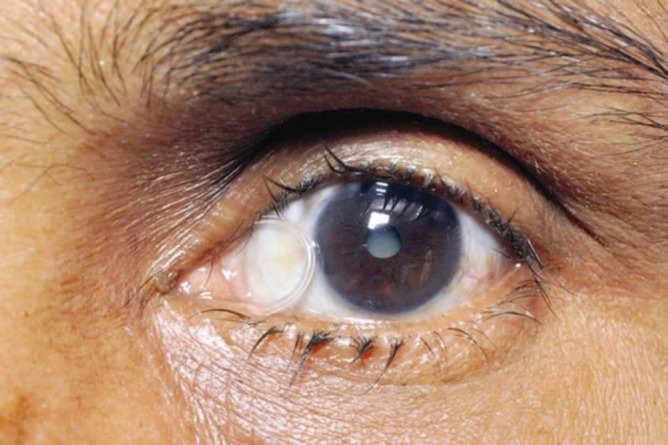

Intermediate complications include granulomas at the rhinostomy site, tube displacements, intranasal synechiae, punctal cheese-wiring [Figure 16], prominent facial scar, and nonfunctional DCR.

Figure 16.

Punctal cheese wiring

Late complications include rhinostomy fibrosis, webbed facial scar, medial canthal distortion, and failed DCR.

Outcomes of external DCR

A successful DCR is a one where there is both anatomical as well as functional patency. The passage should be patent on syringing and the patient should be free of symptoms. The reported success rates of external DCR in literature varies between 85-99%.[1–3,9–11] These rates were presumed to be much higher as compared to endonasal or transcanalicular but increasingly literature shows comparable results between both the approaches.[12–15]

Footnotes

Source(s) of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Tarbet KJ, Custer PL. External dacryocystorhinostomy. Surgical success, patient satisfaction and economic costs. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1065–70. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30910-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welham RA, Henderson PH. Results of dacryocystorhinostomy. Analysis of causes for failures. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 1973;93:601–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linberg JV, McCormick SA. Primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction: A clinico-pathological report. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:1055–62. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartley GB. Acquired lacrimal drainage obstructions: An etiologic classification system, case reports and review of literature. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;8:237–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olver J. Colour Atlas of Lacrimal Surgery. 1st ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Hienemann; 2006. External dacryocystorhinostomy. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldeschi L, Macandie K, Hintschich CR. The length of unsutured mucosal margin in external dacryocystorhinostomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1004;138:840–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turkcu FM, Oner V, Tas M, Alakus F, Iscan Y. Anastomosis of both posterior and anterior flaps or only anterior flaps in external dacryocystorhinostomy. Orbit. 2012 doi: 10.3109/01676830.2012.711884. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNab A. Manual of Orbital and Lacrimal surgery. 2nd ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Hienemann; 1998. Dacryocystorhinostomy. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen N, Sharir M, Moverman DC, Rosner M. Dacryocystorhinostomy with silicone tubes: Evaluation of 253 cases. Ophthalmic Surg. 1989;20:115–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dresner SC, Klussman KG, Meyer DR. Outpatient dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmic Surg. 1991;22:222–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emmerich KH, Busse H, Meyer-Rusenberg HW. Dacryocystorhinostomia externa. Ophthalmologe. 1994;91:395–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cokkeser Y, Evereklioglu C, Er H. Comparitive external versus endonasal dacryocystorhinosotmy: results in 115 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:488–91. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.105470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malhotra R, Wright M, Olver JM. A consideration of the time taken to do a dacryocystorhinostomy surgery. Eye. 2003;17:691–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolman PJ. Comparison of external dacyrocystorhinostomy with non-laser endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01452-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartikainen J, Grenman R, Puukka P, Seppa H. Prospective randomized comparison of external dacyrocystorhinostomy and endonasal laser dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1106–13. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)96015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]