Abstract

The crabapple mangrove tree, Sonneratia caseolaris Linn. (Family: Sonneratiaceae), is one of the foreshore plants found in estuarine and tidal creek areas and mangrove forests. Bark and fruit extracts from this plant have previously been shown to have an anti-oxidative or cytotoxic effect, whereas flower extracts of this plant exhibited an antimicrobial activity against some bacteria. According to the traditional folklore, it is medicinally used as an astringent and antiseptic. Hence, this investigation was carried out on the extract of the leaves, pneumatophore and different parts of the flower or fruit (stamen, calyx, meat of fruit, persistent calyx of fruit and seeds) for antibacterial activity using the broth microdilution method. The antibacterial activity was evaluated against five antibiotic-sensitive species (three Gram-positive and two Gram-negative bacteria) and six drug-resistant species (Gram-positive i.e. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium and Gram-negative i.e. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-Escherichia coli, multidrug-resistant–Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acenetobacter baumannii). The methanol extracts from all tested parts of the crabapple mangrove tree exhibited antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, but was mainly a bactericidal against the Gram-negative bacteria, including the multidrug-resistant strains, when compared with only bacteriostatic on the Gram-positive bacteria. Using Soxhlet apparatus, the extracts obtained by sequential extraction with hexane, dichloromethane and ethyl acetate revealed no discernable antibacterial activity and only slightly, if at all, reduced the antibacterial activity of the subsequently obtained methanol extract. Therefore, the active antibacterial compounds of the crabapple mangrove tree should have a rather polar structure.

Keywords: Antimicrobial activity, bactericidal, crabapple mangrove tree, drug resistant bacteria, Sonneratia caseolaris Linn

The crabapple mangrove tree, locally known as Lumpoo (in Thailand) or Berembang (in Malaysia and Singapore), Sonneratia caseolaris Linn. (Myrtales: Lythraceae), is one of the foreshore plants in the family Sonneratiaceae that is found in the less saline parts of mangrove forests often along tidal creeks with slow moving water and on deep muddy soil but never on coral banks. This plant is a medium-sized (2-20 m height) evergreen tree with oblong or obovate-elliptic coriaceous leaves and unique pneumatophores[1,2] with a height of 50-90 cm and diameter of 7 cm. Previous research has reported that crabapple mangrove tree leaf extracts have antioxidant activities, when examined by the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) assay, and were potentially linked to the presence of two flavonoids (luteolin and luteolin-7-O-β-glucoside) that were found to be antioxidants[2]. In addition, a weak in vitro cytotoxic activity against human cancer cell lines was reported, but none of the 24 isolated compounds showed any antibacterial activity[3]. Likewise, the nine compounds isolated from the fruits of this tree showed some cytotoxic activity but were not screened for the presence of antibacterial activity[4].

Some parts of this tree are traditionally used in folklore medicine and include the pounded leaves or fruits as antiseptic poultices for cuts, sprains and swellings, an oral astringent as well as for the treatment of haematuria and small pox, arresting haemorrhage, and the unripe and ripe fruits were used for coughs and the treatment of parasite infections[1,5]. Burmese and Indian have applied cork of tree as poultice for wounds and bruised wound whereas Malayans used the peel of mature fruit as anthelmintic and used smashed leaves to heal urinary hemorrhage[6].

In comparison with other mangrove trees, the extract of calyx, stamen (parts of flowers) and fruits exhibited a relatively high antioxidant activity, by the DPPH assay, with an ED50 of 6.10, 2.93 and 4.17 μg/ml, respectively, whereas the fruit extract showed a high lipid peroxidation inhibition activity with an IC50 of 83 ng/ml[7]. Morphological characteristics of this tree have been reported[8,9]. However, there have been only a few studies regarding the pharmacological activities for the extract of this plant. The antimicrobial activity of flowers have been reported in comparison with other flower extracts[10].

Infectious diseases are still a major threat to public health, despite the enormous progress in human medicine. Their impact is particularly large in developing countries due to the relative unavailability of medicines (as well as the compounding poor nutritional and sanitation status) and the emergence of widespread drug resistance[11–13]. The increasing emergence of serious multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-positive infections, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)[14] and MDR Gram-negative infections, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MDR), extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs)-producing Enterobacteriaceae and MDR-Acinetobacter baumannii[15,16] has led to an emerging crisis with increased mortality, longer hospital stays and higher hospital costs compared with infections associated with susceptible strains[17–20].

A new more effective antibacterial agent, especially one against MDR pathogens is really needed. The aim of this study was to investigate the antimicrobial activity of extracts from different parts of the crabapple mangrove tree using the broth microdilution method against representative drug-sensitive and MDR strains of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ninety six well plates (flat bottom with lid) (Corning Inc., One Riverfront Plaza, NY, USA), Muller Hinton Broth (MHB) and Muller Hinton Agar (MHA) (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and chloramphenicol (Sigma-Aldrich, Buchs SG, Switzerland ) were used. Sodium chloride and dimethysulphoxide (DMSO) were purchased from P. C. Drug Center Co., Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand.

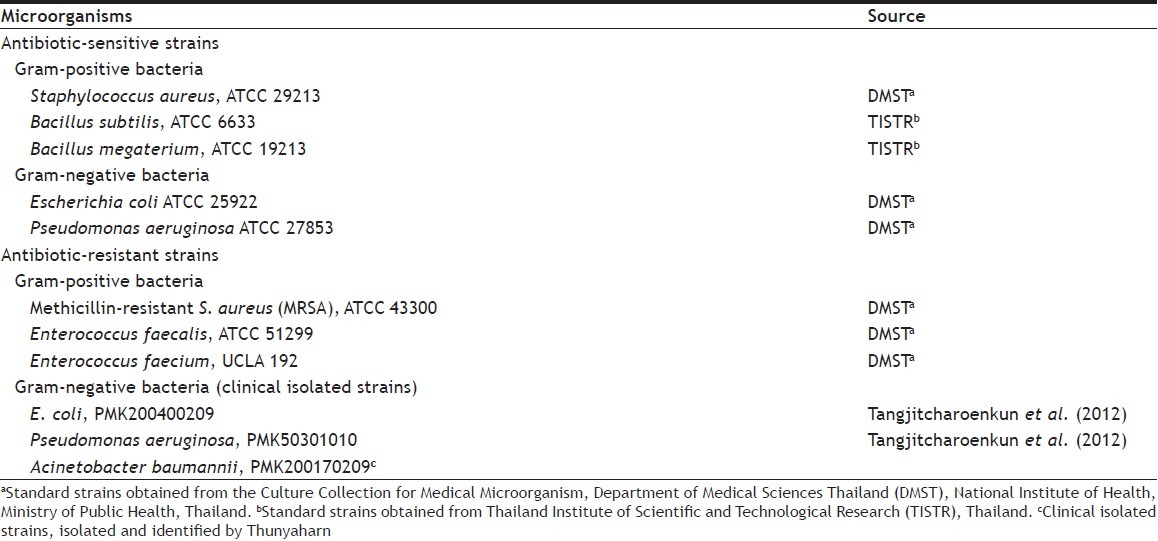

Table 1 shows, 11 bacterial strains obtained from 8 different species that were tested for antimicrobial activity. The three MDR bacteria, isolated by Tangjitcharoenkun et al., used in this study were the ESBL-producing Escherichia coli PMK200400209 and P. aeruginosa (MDR) PMK503010109 strain[21].

TABLE 1.

BACTERIAL STRAINS/SPECIES USED IN THIS STUDY TO SCREEN FOR ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY

The A. baumannii PMK200170209 strain reported in this study was isolated as a pan-drug resistant (PDR) strain from a Thai patient who was treated for lower urinary tract infection at Phamongutklao hospital in Thailand on February 2009. The strain showed resistance to all beta-lactam antibiotics, aminoglycosides, quinolones/fluroquinolones and trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole, whereas it was sensitive to colistin and tigecycline (data not shown).

Preparation of crabapple mangrove tree extracts:

The stamen, calyx, meat of the fruit, persistent calyx of the fruit, seeds, leaves and pneumatophores of the crabapple mangrove tree were collected from Samuthsongkram, Thailand, in October 2008. Voucher specimens were deposited at Department of Pharmacognosy, Silpakorn University in Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, with voucher reference numbers sc 01-07. The plant parts were dried with hot air oven at 60° and then ground by cutting mill using Sieve #30. The high performance liquid chromatography–ultraviolet spectrophotometric (HPLC-UV) method was used by our research group for the simultaneous determination of the three active compounds (gallic acid, luteolin and luteolin-7-O-glucoside) to evaluate the quality of the extracts as described[22]. The HPLC separation was performed on a RP-18 semi-preparative column (250×4.6 mm i.d.; 10 μm) with a gradient of acetonitrile and 0.1% (v/v) aqueous phosphoric acid, at a flow rate of 5.0 ml/min, detected at 280 nm. The ground powder of the different parts of the crabapple mangrove tree, selected as the leaves (L), pneumatophore (E), flower [stamen (T) and calyx (P)] and fruit [meat of fruit (F), persistent calyx of fruit (C) and seeds (S)] were individually weighed and subsequently macerated either with methanol alone or in four organic solvents, in sequential order at 1:4 (w/v) ratio of dried sample (g) and solvent (ml). When methanol was used, the extraction was performed at room temperature (28°) for 72 h. When organic solvents were used, sequential extraction was performed, using Soxhlet's apparatus, wherein the dried plant samples were extracted, with each solvent in the following order: (1) hexane, (2) dichloromethane, (3) ethyl acetate and (4) methanol, for 24 h. In all cases, the percolate was filtered through Whatman® No. 1 filter paper until clear and the extracts were then subjected to evaporation using a rotary evaporator (Buchi R205, BUCHI (Thailand) Ltd., Klongsan, Bangkok, Thailand) until dry, collected and weighed. The dried extract was then dissolved in DMSO and subsequently diluted into MHB for screening in antibacterial activity assays.

Antibacterial activity assay:

MHA plates and MHB were used as the solid and liquid culture media, respectively, for the assay of the number of viable bacteria by total plate counting, and the growth of the bacteria, respectively. Screening for antibacterial activity of each extract was assessed using the agar well diffusion assay, modified slightly from that described in Hood et al.[23] The indicator strains from MHA plates were individually inoculated into MHB and were then incubated at 37° for 24 h. Once an actively growing broth culture or suspension of microbes was obtained, the turbidity was adjusted to match that of the standard 0.5 McFarland solution, which correlated to a cell density of approximately 108 cells/ml. Then 30 μl of suspension, containing 2.5, 10 or 20 mg/ml of the test extract, was separately added to each well (6 mm in diameter) of a MHA agar plate freshly spread with 0.1 ml of the test bacterial cell suspension. The plates were incubated at 37° for 24 h and then observed visually for the presence of any inhibition zone around the well. Agar wells loaded with the same amount (30 μl) of DMSO/MHB solvent at the same concentrations and were used as negative controls. The minimum inhibition concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) were measured using the broth microdilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) protocol[24,25]. The assay was performed in a 96-well microtitre plate with a final volume of 100 μl per well. Each well contained 20 μl of the serially diluted plant extract under test, 20 μl of the test bacteria suspension in MHB at 106 CFU/ml and 60 μl of fresh MHB culture broth. Chloramphenicol was employed as a positive control whereas the MHB-diluted DMSO solvent (same concentrations as the test plant extracts) without the test plant extracts was used as the negative control. The assay plate was incubated at 37° for 24 h, whereupon the growth of the test bacteria was examined by visual observation in terms of the turbidity of the culture. The MICs were determined as the lowest concentration of the test compound at which no turbidity from microbial growth could be observed. The MBC values were obtained by re-inoculating 10 μl of each supernatant fluid from the MIC tested wells with no visible turbidity onto fresh MHA plates. The MBC is defined as the lowest concentration of the test compound at which no viable cells were detected on replating.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

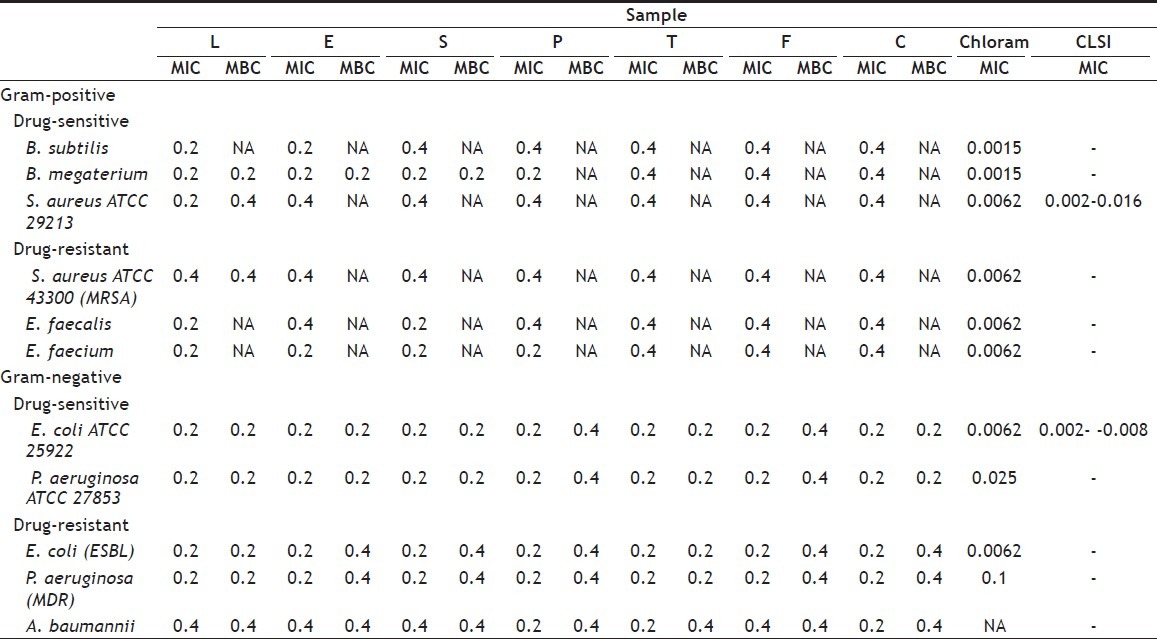

The agar well diffusion assay was employed for the screening of antibacterial activity in different extracts (different solvents and different plant parts) of the crabapple mangrove tree. The methanol extracts of all the plant parts examined, revealed antibacterial activity against all 11 test strains (8 different species) of bacteria, in terms of the appearance of a zone of growth inhibition, around the application well (data not shown). The broth microdilution method was then used to determine the MIC and MBC of each of these extracts, and the results are summarised in Table 2. By comparing the MIC of the standard control group and the standard from CLSI (2010)[24], the MIC value against S. aureus ATCC 29213 and E. coli ATCC 25922 were found to be within the acceptable range of CLSI (Table 2) Although an antibacterial activity (MIC) was detected in the methanol extracts of all 7 crabapple mangrove tree parts against all 11 test bacterial strains, the MBC values (bactericidal activity) showed a different pattern of activity from that of MIC (Table 2). Although all of the methanol samples showed bactericidal effect on all tested Gram-negative bacteria, including both the drug-sensitive E. coli and P. aeruginosa, and MDR ESBL-producing E. coli, P. aeruginosa and PDR-A. baumannii strains, the only bactericidal activity against Gram-positive bacteria was observed with the leaf extract sample against MRSA and the leaf, seeds and pneumatophore extracts against Bacillus megaterium and S. aureus, but not Bacillus subtilis, for the drug-resistant and drug-sensitive bacteria, respectively. The rest of the samples only showed a bacteriostatic effect against the Gram-positive bacteria. Based on the differences in the pattern of the MBC and MIC values against the test bacterial strains, the samples from the seven different parts of the crabapple mangrove tree could be divided into three groups. The first group comprising of leaves showed the strongest antibactericidal activity against two drug-sensitive strains (B. megaterium and S. aureus) and one drug-resistant Gram-positive bacteria (MRSA). The second group comprising pneumatophore and seed samples could eradicate only one Gram-positive bacteria (B. megaterium) and displayed a bacteriostatic effect against the rest of the test Gram-positive bacteria. The third group containing the samples from the stamen, calyx and the meat and calyx of the fruit only displayed a bacteriostatic activity against all test Gram-positive bacteria (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

ANTIBACTERIAL ACTIVITY OF THE METHANOL EXTRACTS OF DIFFERENT PLANT PARTS FROM THE CRABAPPLE MANGROVE TREE

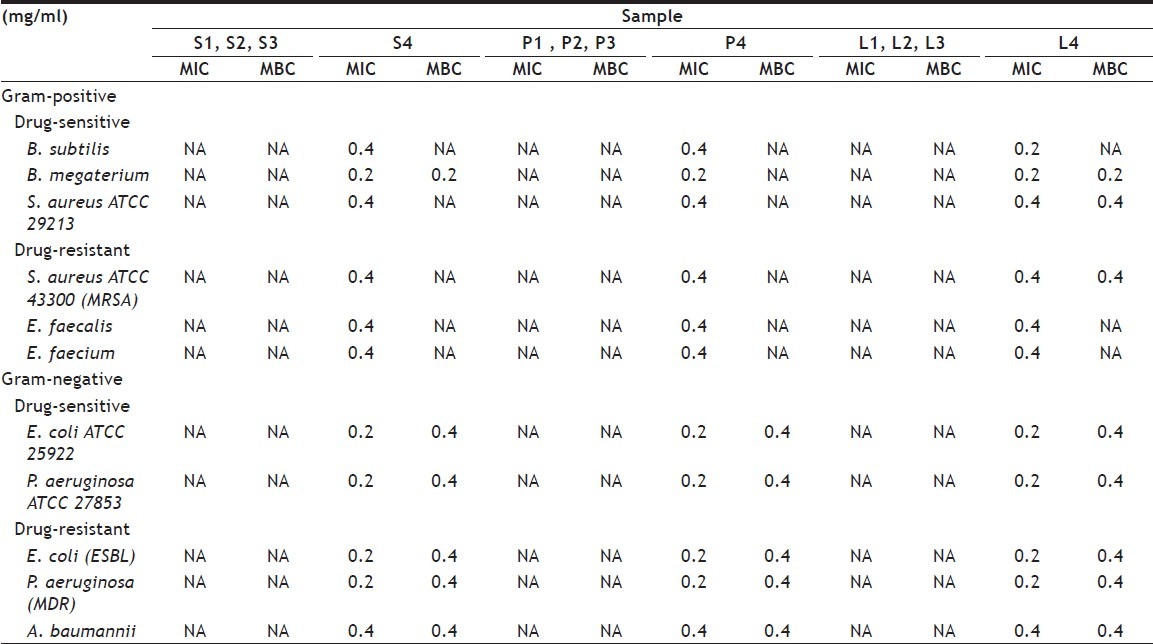

Further, we selected one sample (plant part) from each of the above three groups as representative samples for sequential fractional purification and determination of the antibacterial activity, again based upon the MIC and MBC values (Table 3). It was found that fractions obtained from the sequential extraction with hexane (L1, S1 and P1), dichloromethane (L2, S2 and P2) and ethyl acetate (L3, S3 and P3) showed no detectable antibacterial activity against any of the eleven test strains. Rather, the antibacterial activity was only detected in the methano fractions (samples L4, S4 and P4). As noted before with the direct methanol extracts (Table 2), the antibacterial effect against the Gram-negative bacteria was mostly bactericidal whereas that against the Gram-positive bacteria was bacteriostatic except for B. megaterium that displayed a bactericidal action (Table 3). Indeed, the MIC and MBC activity for the methanol extract following hexane, dichloromethane and ethyl acetate extraction (Table 3) were the same as that of the direct methanol extraction (Table 2) in most cases of the seed and calyx samples, suggesting that the hexane, dichloromethane and ethyl acetate extractions did not remove the active component (s). However, the bactericidal activity of the leaf extract against the Gram-negative bacteria was slightly reduced from 0.2 to 0.4 mg/ml in 4/5 cases.

TABLE 3.

ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY OF THE SEQUENTIAL EXTRACTS OF VARIOUS PART OF THE CRABAPPLE MANGROVE TREE

It was noted that the crabapple mangrove tree extracts exhibited antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including against the MDR strains. The extract exhibited a higher bactericidal action against Gram-negative pathogens than Gram-positive ones. The active fractions were only found in the methanol extractions and were not affected by the prior sequential extraction of hexane, dichloromethane and ethyl acetate (except for perhaps a slight reduction in the bactericidal activity in the leaf extract), suggesting that the antibacterial compound (s) is/are rather hydrophilic. Although all 7 evaluated parts of the crabapple mangrove tree showed antibacterial activity, they differed in their activity levels with the most pronounced being found in the methanol extract of leaves (Table 2). This is of interest since leaves are the easiest source to harvest and the most abundant source. Indeed, the crabapple mangrove tree can recover rapidly after branch removal, regenerating from buds below the bark surface, and is reasonably productive (fast growing).

The antimicrobial action could be due to the flavonoids in this plant[4] but awaits further enrichment and identification of the bioactive component(s) for confirmation. Nevertheless, this result is very interesting since most reports on the effect of plant extracts have, in contrast, shown a greater susceptibility to Gram-positive bacteria than to Gram-negative bacteria[26–29]. Such observations could be explained by the fact that most of the antimicrobial active components identified are less polar compounds that are not water-soluble and so the organic solvent extracts showed a more potent activity[30]. The outer phospholipidic membrane of Gram-negative bacteria with the structural lipopolysaccharide component makes their cell walls largely impermeable to lipophilic solutes, and the porin-based pores form a selective barrier to the hydrophilic solutes with an exclusive limit of about 600 Da[31]. Gram-positive bacteria are, however, more susceptible to non-polar antibacterial agents since their outer peptidoglycan layer is not an effective permeability barrier[32,33]. In this case reported here, the effective antimicrobial activity was found in the methanol extract (Table 3), suggesting a rather polar structure and so is consistent with the observed higher antibacterial activity against the Gram-negative bacteria than the Gram-positive bacteria tested. It may be possible that multiple bioactive compounds are contained in the extracts and that they differentially contribute to the bactericidal effect in Gram-negative and bacteriostatic effect in Gram-positive bacteria. Further isolation and purification of the methanol extracts, especially those of the leaves, are needed to address this and is a currently ongoing study.

The overall results provide a promising basis for the evaluation of the potential use of crabapple mangrove tree leaves as a source of antibiotics for the treatment of specific microbial infections associated with the sensitive pathogens as well as the MDR bacteria studied. Purification of the effective fractions for further elucidation on its pharmacological and cytotoxicity studies is being conducted to confirm the extracts as potential therapeutic agents.

Methanol extracts of all tested parts of the crabapple mangrove tree, S. caseolaris Linn., exhibited broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens, and revealed a significantly higher bactericidal activity against Gram-negative bacteria than Gram-positive bacteria. The methanol extract from leaves contained the highest antibacterial activity and could even kill the MDR Gram-positive (MRSA) and Gram-negative pathogens (ESBL-producing E. coli, MDR P. aeruginosa and the PDR-A. baumannii). Such a high efficacy of the leaf methanol extracts of the crabapple mangrove tree against MDR and PDR strains suggests its potential to further develop as an antibacterial agent.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research work was kindly supported by Research and Development Institute and the Faculty of Pharmacy, Silpakorn University. We would like to thank the Department of Medical Sciences, National Institute of Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand (DMST) and the Thailand Institute of Scientific and Technological Research (TISTR), Pathum Thani, Thailand, for providing some of the bacterial strains. We also thank Assistant Professors Chantana Wessapan and Dr. Juree Charoenteeraboon for their help and Dr. Robert Butcher for proof reading and language improvement of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Yompakdee et al.: Bactericidal Activity of Crabapple Mangrove Tree Against Multi-drug Resistant Pathogens

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghani A. Medicinal Plants of Bangladesh. 2nd ed. Dhaka: The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh; 2003. p. 382. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadhu S, Ahmed F, Ohtsuki T, Ishibashi M. Flavonoids from Sonneratia caseolaris. J Nat Med. 2006;60:264–5. doi: 10.1007/s11418-006-0029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian M, Dai H, Li X, Wang B. Chemical constituents of marine medicinal mangrove plant Sonneratia caseolaris. Chinese J Oceanol Limnol. 2009;27:288–96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu S-B, Wen Y, Li X-W, Zhao Y, Zhao Z, Hu J-F. Chemical constituents from the fruits of Sonneratia caseolaris and Sonneratia ovata (Sonneratiaceae) Biochem Syst Ecol. 2009;37:11–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duke JA. Sonneratia caseolaris (L.) Engl. Handbook of Energy Crops. 1983. [Last Accessed on 2012 Jul 19]. Available from: http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/duke_energy/Sonneratia_caseolaris.html .

- 6.Perry LM, Metzger J. Medicinal Plants of East and Southeast Asia: attributed properties and uses. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1980. p. 620. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunyapraphatsara N, Jutiviboonsuk A, Sornlek P, Therathanathorn W, Sa HS, Fong H, et al. Pharmacological studies of plants in the mangrove forest. Thai J Phytopharm. 2003;10:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen ZL. The morphology and anatomy of Sonneratia Linn. f. in China. J Trop Subtrop Bot. 1996;4:18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang RJ, Chen ZY. Systematics and biogeography study on the family Sonneratiaceae. Guihaia. 2002;22:214. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wessapan C, Charoenteeraboon L, Wetwitayaklug P, Paechamud T. Planta Med. 55th International Congress and Annual Meeting of the Society for Medicinal Plant Research, Graz, Austria. 2007:886–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh C. Molecular mechanisms that confer antibacterial drug resistance. Nature. 2000;406:775–81. doi: 10.1038/35021219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh C. Where will new antibiotics come from? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okeke IN, Laxminarayan R, Bhutta ZA, Duse AG, Jenkins P, O’Brien TF, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. Part I: Recent trends and current status. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:481–93. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stenhem M, Ortqvist A, Ringberg H, Larsson L, Olsson Liljequist B, Haeggman S, et al. Imported methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:189–96. doi: 10.3201/eid1602.081655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunz AN, Brook I. Emerging resistant Gram-negative aerobic bacilli in hospital-acquired infections. Chemotherapy. 2010;56:492–500. doi: 10.1159/000321018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zavascki AP, Carvalhaes CG, Picão RC, Gales AC. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii: Resistance mechanisms and implications for therapy. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8:71–93. doi: 10.1586/eri.09.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans HL, Lefrak SN, Lyman J, Smith RL, Chong TW, McElearney ST, et al. Cost of Gram-negative resistance. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:89–95. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251496.61520.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sostarich AM, Zolldann D, Haefner H, Luetticken R, Schulze-Roebecke R, Lemmen SW. Impact of multiresistance of gram-negative bacteria in bloodstream infection on mortality rates and length of stay. Infection. 2008;36:31–5. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-6316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giske CG, Monnet DL, Cars O, Carmeli Y. Reaction on antibiotic resistance. Clinical and economic impact of common multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:813–21. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01169-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shorr AF. Review of studies of the impact on Gram-negative bacterial resistance on outcomes in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1463–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819ced02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tangjitcharoenkun J, Chavasiri W, Thunyaharn S, Yompakdee C. Bactericidal effects and time-kill studies of the essential oil from the fruits of Zanthoxylum limonella on multi-drug resistant bacteria. J Essent Oil Res. 2012;24:363–70. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Limmatvapirat C, Sukjindasathein S, Charoenteeraboon J, Phaechamud T. Determination of three components in Sonnertia caseolaris L. by high performance liquid chromatography. Drug Metab Rev. 2009;41:81. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hood JR, Wilkinson J, Cavanagh M, Heather MA. Evaluation of common antibacterial screening methods utilized in essential oil research. J Essent Oil Res. 2003;15:428–33. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Twentieth Information Supplement. Wayne, PA: 2010. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M100-S20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuete V, Wansi JD, Mbaveng AT, Sop MM, Tadjong AT, Beng VP, et al. Antimicrobial activity of the methanolic extract and compounds from Teclea afzelii (Rutaceae) South Afr J Bot. 2008;74:572–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alonso Paz E, Cerdeiras MP, Fernandez J, Ferreira F, Moyna P, Soubes M, et al. Screening of Uruguayan medicinal plants for antimicrobial activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;45:67–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)01192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vlietinck AJ, Van Hoof L, Totté J, Lasure A, Vanden Berghe D, Rwangabo PC, et al. Screening of hundred Rwandese medicinal plants for antimicrobial and antiviral properties. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;46:31–47. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudi AC, Umoh JU, Eduvie LO, Gefu J. Screening of some Nigerian medicinal plants for antibacterial activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;67:225–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palombo EA, Semple SJ. Antibacterial activity of traditional Australian medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;77:151–7. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parekh J, Karathia N, Chanda S. Screening of some traditionally used medicinal plants for potential antibacterial activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;68:832–4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikaido H, Vaara M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scherrer R, Gerhardt P. Molecular sieving by the Bacillus megaterium cell wall and protoplast. J Bacteriol. 1971;107:718–35. doi: 10.1128/jb.107.3.718-735.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arias ME, Gomez JD, Cudmani NM, Vattuone MA, Isla MI. Antibacterial activity of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of Acacia aroma Gill. ex Hook et Arn. Life Sci. 2004;75:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]