Abstract

Natural product discovery by random screening of broth extracts derived from cultured bacteria often suffers from high rates of redundant isolation, making it ever more challenging to identify novel biologically interesting natural products. Here we show that homology-based screening of soil metagenomes can be used to specifically target the discovery of new members of traditionally rare, biomedically relevant natural product families. Phylogenetic analysis of oxy-tryptophan dimerization gene homologs found within a large soil DNA library enabled the identification and recovery of a unique tryptophan dimerization biosynthetic gene cluster, which we have termed the bor cluster. When heterologously expressed in Streptomyces albus, this cluster produced an indolotryptoline antiproliferative agent with CaMKIIδ kinase inhibitory activity (borregomycin A), along with several dihydroxyindolocarbazole anticancer/antibiotics (borregomycins B–D). Similar homology-based screening of large environmental DNA libraries is likely to permit the directed discovery of new members within other previously rare families of bioactive natural products.

Keywords: antitumor, uncultured microbes, bisindole alkaloid, indenotryptoline

Natural product discovery programs have long relied on the random screening of culture broth extracts to identify metabolites with bioactive properties. Unfortunately, it has become increasingly difficult to isolate new members of biomedically interesting classes of compounds using random screening strategies due to the phenomenon of redundant isolation (1). Homology-based screening of metagenomes, which relies on the PCR amplification of conserved natural product biosynthetic gene sequence motifs to identify and recover gene clusters from environmental DNA (eDNA) libraries, offers a potential solution to this dilemma by allowing the targeted recovery of specific biosynthetic pathways from the genomes of all bacterial species present within an environmental sample. Bioinformatics analyses of sequences recovered through homology screening allow for the exclusion of sequences that are likely associated with gene clusters encoding for previously encountered metabolites, significantly reducing the likelihood for redundant isolation and increasing the likelihood of finding hitherto rare metabolites. Thus, homology-based screening coupled with phylogenetic analyses of sequences captured in large eDNA libraries should permit the routine discovery of biosynthetic gene clusters encoding for metabolites belonging to even previously rare families of bioactive natural products.

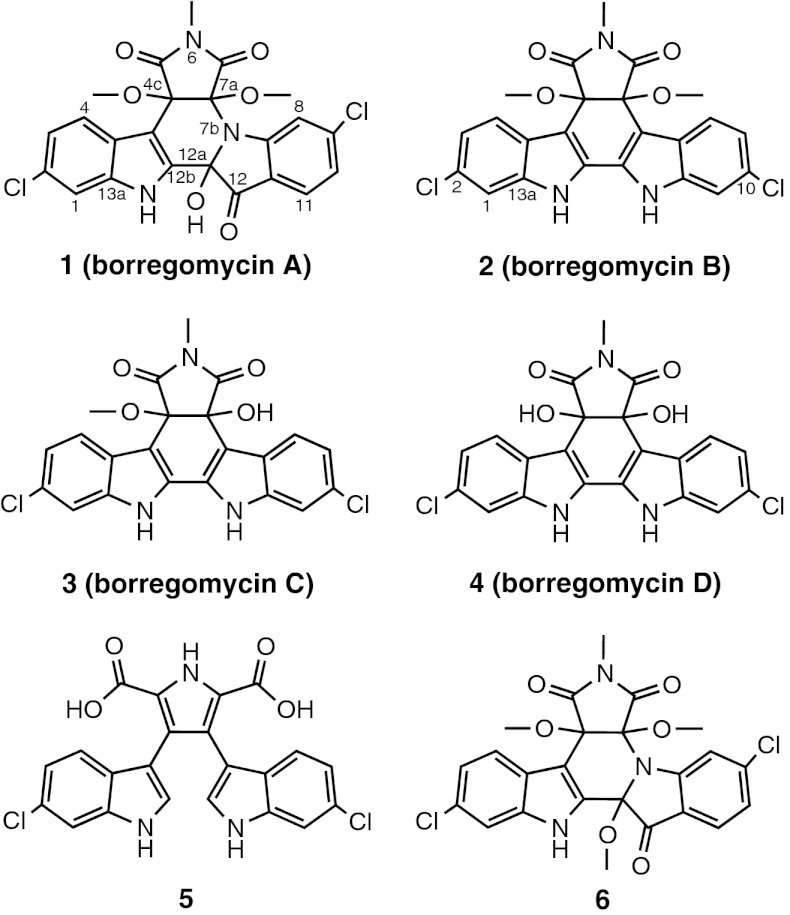

The biosynthesis of a number of pharmacologically interesting bacterial secondary metabolites starts with the dimerization of tryptophan (2). Most bacterial tryptophan dimers that have been characterized to date are members of the indolocarbazole family (3), which have been the inspiration for the development of an entire class of clinically relevant kinase inhibitor antineoplastic agents (4). Although indolocarbazole structures have been commonly found in culture-based screening programs with more than 100 natural members described to date (3), the related indolotryptoline (dihydroxy-dihydro-pyrido[1,2-a:3,4-b′]diindole) family of tryptophan dimers has seldom been seen. In fact, only two natural tryptophan dimer-based indolotryptolines, BE-54017 (5) and its desmethyl derivative cladoniamide (6), have been reported so far. Consequently, the bioactivity of the indolotryptoline family remains poorly understood, despite having in vitro antiproliferative activity comparable to that of the indolocarbazole family (7). Using homology-guided metagenomic library screening, we report here the discovery, cloning, and heterologous expression of the indolotryptoline-based bor biosynthetic gene cluster, which encodes for the borregomycins (Fig. 1). The borregomycins are generated from a branched tryptophan dimer biosynthetic pathway, with one branch leading to borregomycin A (1), a unique indolotryptoline antiproliferative agent with kinase inhibitor activity, and a second branch leading to borregomycins B–D (2–4), a unique series of dihydroxyindolocarbazole anticancer/antibacterial agents.

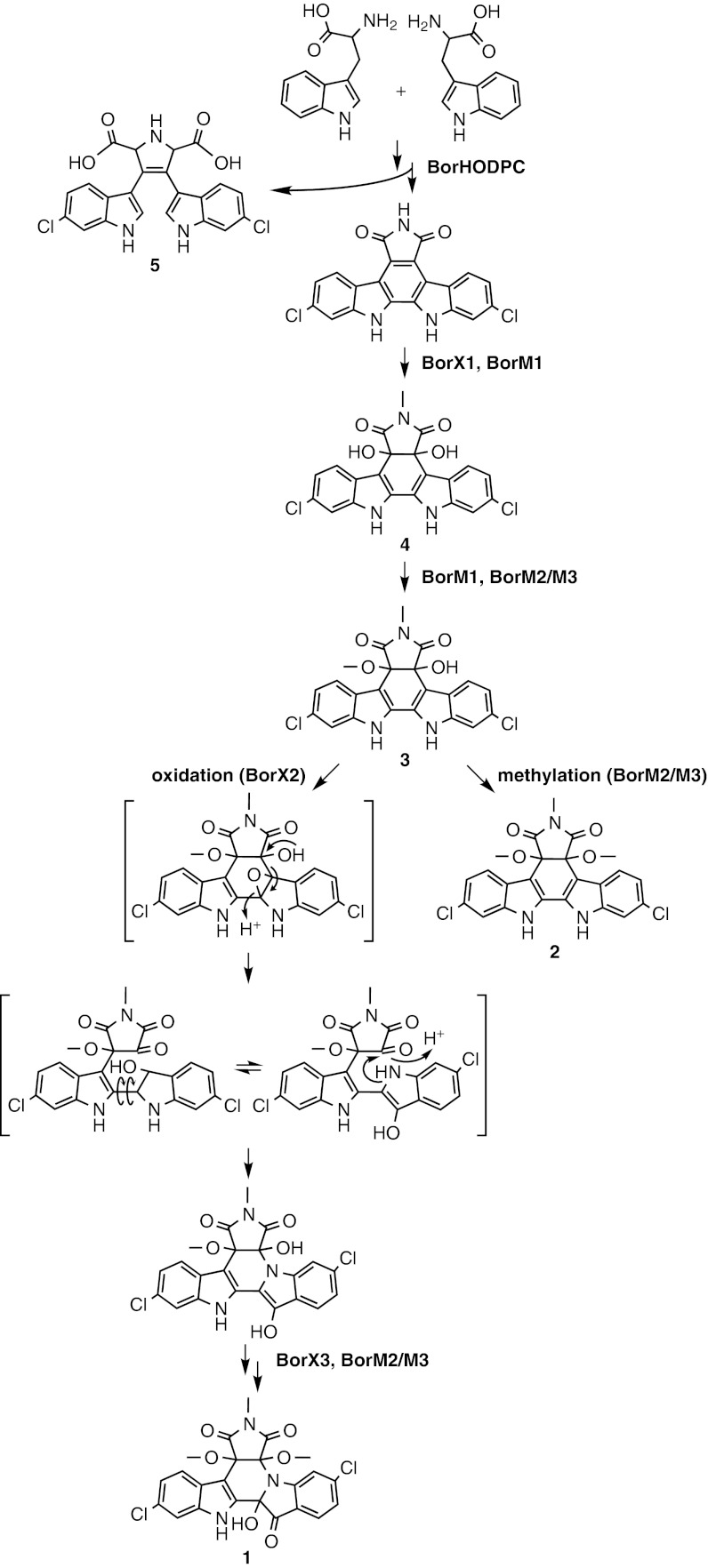

Fig. 1.

The borregomycins. Indolotryptoline-based borregomycin A (1), dihydroxyindolocarbazole-based borregomycins B–D (2–4), dichlorochromopyrrolic acid (5), and O-methyl-borregomycin A (6) were isolated from S. albus harboring the eDNA-derived bor gene cluster.

Results and Discussion

A single gram of soil is predicted to contain thousands of unique bacterial species, the vast majority of which remain recalcitrant to culturing in the laboratory (8). Cloning DNA that has been extracted directly from soil, therefore, provides a means of capturing the biosynthetic potential encoded within the genomes of thousands of largely uncultured bacterial species in a single genomic DNA library. The enormous unexplored biosynthetic diversity found in large soil eDNA libraries makes them promising starting points for homology-guided discovery efforts. For this study, a cosmid library containing more than 10 million unique members was constructed using eDNA extracted from Anza-Borrego Desert soil.

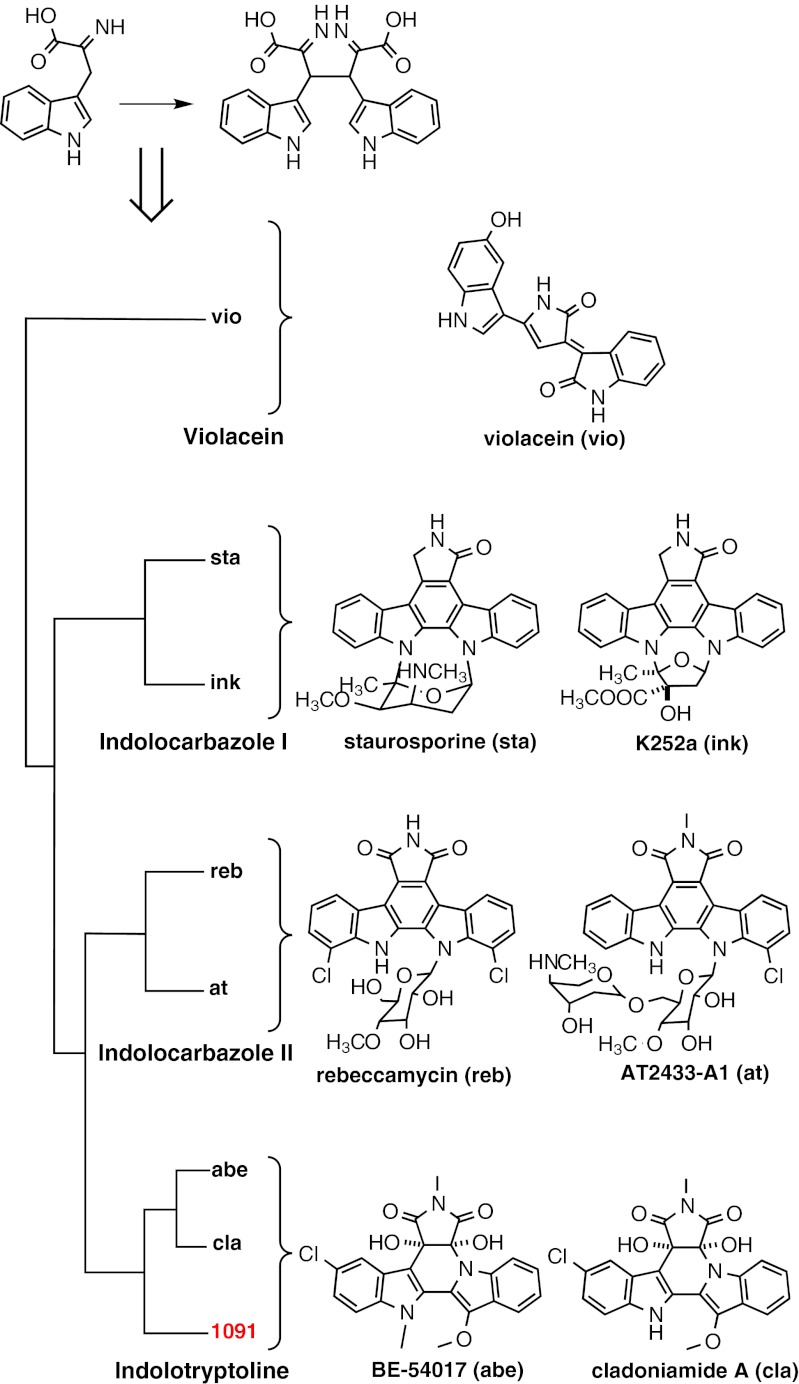

All functionally characterized bacterial biosynthetic gene clusters encoding for members of the indolocarbazole, indolotryptoline, and violacein families of tryptophan dimers contain a highly conserved gene responsible for oxy-tryptophan dimerization (2), the prototypical member of which is staD from the staurosporine biosynthetic gene cluster (9). A ClustalW-based phylogenetic tree of staD homologs reveals the clustering of sequences according to the specific structural class of the tryptophan dimer to which these sequences are linked (Fig. 2). Because this single gene can be used to predict the class of tryptophan dimer encoded by a gene cluster, we hypothesized that we could target the discovery of unique indolotryptoline-encoding biosynthetic gene clusters by screening for oxy-tryptophan dimerase genes that fall into the same clade as the abeD and claD genes from the BE-54017 and cladoniamide biosynthetic gene clusters, respectively.

Fig. 2.

ClustalW-based phylogenetic tree of oxy-tryptophan dimerization genes. (Top) StaD-like genes that encode for oxy-tryptophan dimerization enzymes are conserved among characterized bacterial tryptophan dimer gene clusters. (Left) Phylogenetic tree of staD-like oxy-tryptophan dimerization genes. Sequence 1091 was recovered from an Anza-Borrego Desert soil eDNA cosmid library. (Right) Compounds produced by the pathways associated with each staD-like homolog used to generate the phylogenetic tree.

Degenerate PCR primers designed to recognize conserved regions in staD homologs from all known bacterial tryptophan dimer gene clusters were used to screen the Anza-Borrego Desert soil eDNA library for staD-like sequences. PCR amplicons from this screen were sequenced and phylogenetically compared with known oxy-tryptophan dimerase genes (Fig. 2). As expected from the frequent discovery of indolocarbazole metabolites in culture-based studies, a number of oxy-tryptophan dimerase amplicons falling into the staurosporine (indolocarbazole I) and rebeccamycin (indolocarbazole II) clades were found in the library. In addition to these common sequences, we also found one amplicon (Fig. 2, amplicon 1091) that fell within the same clade as the indolotryptoline biosynthesis-associated abeD and claD genes. This sequence, amplicon 1091, was used as a probe to guide the recovery of the cosmid clone containing the eDNA gene cluster from which it arose.

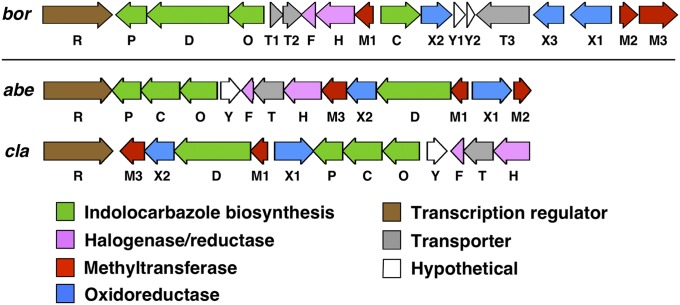

Sequencing of the eDNA cosmid clone containing the abeD/claD-related tryptophan dimer gene sequence (clone AB1091) revealed the bor gene cluster, which resembles, but is noticeably distinct from, both the BE-54017 (abe) (7) and the cladoniamide (cla) (10) gene clusters (Fig. 3). As seen in the abe and cla clusters, the bor cluster contains a complete set of conserved indolocarbazole biosynthetic genes (borO, -D, -C, and -P), a single halogenase gene (borH), and homologs of the two oxidoreductase genes (borX1, borX2) that are known to encode the transformation of indolocarbazole precursors into indolotryptolines. Additionally, the bor cluster uniquely contains a third oxidoreductase gene (borX3) that is not seen in either the abe or the cla cluster. Similar to the abe cluster, three methyltransferase genes (borM1, -M2, and -M3) are present in the bor cluster; however, borM2 and borM3 do not show significant sequence identity to any of the abe methyltransferases. As suggested by our initial phylogenetic analysis of the bor oxy-tryptophan dimerase gene amplicon, bioinformatics analysis of the complete bor cluster further suggested that it was likely to encode for a new indolotryptoline-based metabolite.

Fig. 3.

Indolotryptoline biosynthetic gene clusters. The borregomycin (bor), BE-54017 (abe), and cladoniamide (cla) biosynthetic gene clusters produce indolotryptoline-based metabolites.

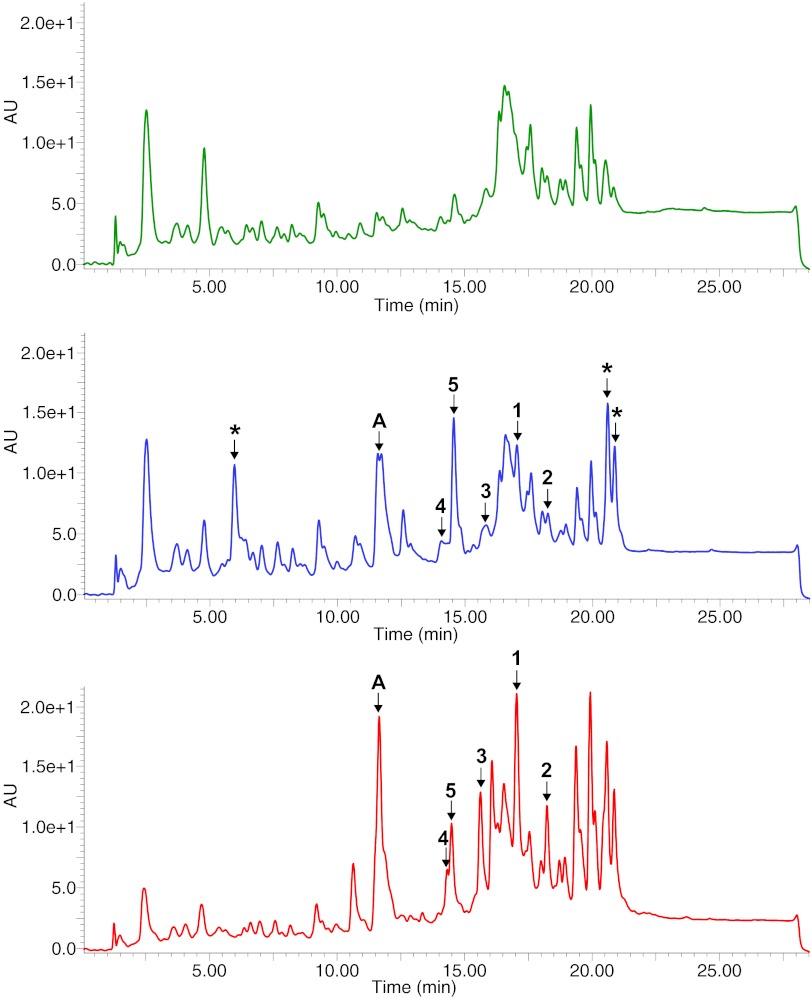

In an effort to access the metabolite(s) encoded by the bor cluster, an eDNA clone harboring this cluster (clone AB1091) was conjugated into Streptomyces albus, which has been successfully used as a heterologous expression host for other tryptophan dimer-encoding gene clusters (11, 12). However, in the case of the bor cluster, most clone-specific metabolites were produced by S. albus at such low levels that it was not possible to isolate sufficient quantities for structural elucidation. In genome-mining studies with cultured bacteria, it has been possible to increase metabolite production from “silent/cryptic” biosynthetic pathways by overexpressing positive acting transcriptional regulators found within gene clusters of interest (13, 14). A putative transcription factor from the bor cluster, borR, was therefore cloned into a Streptomyces expression vector (pIJ10257) under the control of the strong constitutive ermE* promoter and cotransformed into S. albus along with the cosmid AB1091. In addition to the ermE* promoter, this Escherichia coli/Streptomyces shuttle expression vector contains an origin of transfer (oriT), a hygromycin resistance marker, and the Streptomyces φBT1 integration system that makes it compatible with the φC31 integration system and apramycin resistance marker used to integrate the AB1091 cosmid into the S. albus genome. Constitutive expression of borR in the S. albus background containing AB1091 resulted in increased production of clone-specific metabolites to a level that permitted their isolation and structural characterization (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

BorR induction results in increased borregomycin production. Shown are analytical HPLC HPLC-UV chromatograms (reversed-phase C-18; linear gradient of 80:20 water:methanol to 0:100 water:methanol) of culture broth extracts of S. albus harboring an empty vector as a negative control (green), the bor pathway alone (blue), or S. albus harboring the bor pathway as well as the borR transcriptional regulator overexpression construct (red). Compounds 1–5 represent all of the detected metabolites that are specific to the bor cluster. With bor gene cluster alone, the shunt product 5 accumulates as the major clone-specific product. When the borR expression construct is present, compounds 1 and 2, the predicted final products of the bor cluster, accumulate at higher levels. Peaks marked with an asterisk (*) are produced at high levels in S. albus harboring the bor cluster, but they are also present in negative control extracts and are thus not clone specific. The peaks marked “A” are present in extracts of S. albus harboring the bor gene cluster and not in the negative control extracts. However, these low molecular weight compounds (predicted molecular masses of 179 and 195 mass units) are also seen in extracts from S. albus cultures harboring other indolotryptoline gene clusters (e.g., BE-54017) and are therefore likely common shunt products of indolotryptoline biosynthesis.

In the presence of the borR overexpression construct, the bor gene cluster encodes for the production of five detectable clone-specific metabolites in S. albus (1–5) (Figs. 1 and 4). On the basis of extensive 1D and 2D NMR analysis, compound 1 was determined to be a unique trimethylated indolotryptoline and compounds 2–4 were found to be a unique series of tri-, di-, and monomethylated dihydroxyindolocarbazoles, respectively (SI Text and Figs. S1–S7). Compounds 1–4 have been named borregomycin A–D after the geographic origin of the soil from which the bor cluster was cloned. Two unnamed compounds, 5 and 6, were also isolated in this study (Fig. 1). Compound 5 is a dichlorinated derivative of chromopyrrolic acid, a known shunt product in tryptophan dimer biosynthesis. Compound 6 is the C-12a O-methyl analog of borregomycin A. This compound is not seen in the crude extract (Fig. 4) and is therefore assumed to be an artifact that arises from methanolysis of borregomycin A during the isolation protocol.

On the basis of their final structures, sequence homology arguments, and precedents from previous studies of tryptophan dimer biosynthesis, the biosynthesis of borregomycins A–D can be rationalized as outlined in Fig. 5. Similar to the biosynthesis of rebeccamycin and BE-54017, the biosynthesis of the borregomycins is likely initiated by the chlorination of L-tryptophan by the halogenase BorH, followed by the construction of an indolocarbazole using the set of conserved indolocarbazole biosynthetic enzymes BorO, -D, -P, and -C. The resulting 2,10-halogenation pattern is not seen in any previously reported indolotryptoline- or indolocarbazole-based metabolite. This is consistent with the fact that BorH is more closely related to known tryptophan 6-halogenases than halogenases found in other tryptophan dimer gene clusters. On the basis of sequence homology to enzymes from BE-54017 biosynthesis, oxidoreductase BorX1 is predicted to install the C-4c/C-7a hydroxyl groups and putative N-methyltransferase BorM1 is predicted to methylate N-6 to generate borregomycin C (4). One of the two remaining methyltransferases unique to the bor cluster, collectively referred to as BorM2/BorM3, is then predicted to O-methylate 4 on either the C-4c or the C-7a hydroxyl to yield dimethylated 3. The regiospecificity of this O-methylation reaction is not known.

Fig. 5.

Proposed scheme for the biosynthesis of the borregomycins. The borregomycins are predicted to arise from a branched biosynthetic pathway with one branch of the pathway giving rise to the indolotryptoline-based metabolite borregomycin A (1) and a second branch giving rise to the dihydroxyindolocarbazole-based metabolites borregomycin B–D (2–4). Compound 5 is a dichlorinated derivative of chromopyrrolic acid, a known shunt product in tryptophan dimer biosynthesis.

The concurrent production of both borregomycin A (1) and borregomycin B (2) from 3 can be rationalized by the existence of a branch in the biosynthetic scheme where 3 initially undergoes either oxidation by BorX2 or further methylation by BorM2/M3. Should BorM2/M3 act directly on 3 to generate the trimethylated borregomycin B (2), transformation of the indolocarbazole into an indolotryptoline by BorX2 is inhibited as a result of both the C-4c and C-7a hydroxyls being blocked with methyls, rendering 2 as the terminal product of one branch of the bor pathway. If, however, the C-7a hydroxyl of 3 is available for deprotonation, BorX2 can promote the rearrangement of the indole via epoxide-driven fragmentation of the C-7a/C-7b bond followed by rotation of the indole around the C-12a/C-12b axis and formation of the C-7a/N-7b bond. The resulting indolotryptoline intermediate is then predicted to undergo methylation on the C-7a hydroxyl (BorM2/M3) followed by BorX3-dependent oxidation across the C-12/C-12a bond to yield borregomycin A (1).

Branched biosynthetic pathways are quite common in natural product biosynthesis. In most cases, however, they generate either collections of compounds from the same structural family or relatives of a single major product that are labeled as intermediates, degradation products, or shunt products (15, 16). In rarer cases, for example in methymycin/pikromycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces venezuelae (17) and saliniketal/rifamycin biosynthesis in Salinispora arenicola (18), pathways have been found to produce terminal biologically active metabolites that are representative of different structural classes.

Tryptophan dimers and other bisindole compounds exhibit diverse cytotoxic activities (3, 4), and therefore the borregomycins were assayed for cytotoxicity against a panel of model organisms (Table 1). Both borregomycin A (1) and borregomycin B (2) exhibit low micromolar antiproliferative activities against human colon cancer HCT116 cells, comparable to the activity reported for the extensively studied indolocarbazole rebeccamycin [half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50): 0.72 μM] (19). Borregomycin B (2) is also a Gram-positive antibiotic; however, at the highest concentration tested, borregomycin A (1) did not inhibit the growth of any of the bacteria we tested (Table 1). The bor pathway therefore encodes not only for metabolites from distinct structural families, but also for metabolites with distinct bioactivities.

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity data for the borregomycins

| Organism | 1 (A) | 2 (B) | 3 (C) | 4 (D) | 5 | 6 |

| Human HCT116 IC50, µM | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 48 | 1.1 |

| S. aureus USA300 MIC, µg/mL | >25 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 3.1 | >25 | >25 |

| B. subtillis Sr168 MIC, µg/mL | >25 | 0.20 | 1.6 | 3.1 | >25 | >25 |

| E. coli EC100 MIC, µg/mL | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| S. cerevisae W303 MIC, µg/mL | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

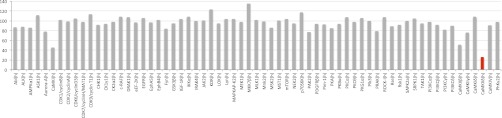

Although reports on the potential mode of action of members of the indolotryptoline family are limited to a single recent study of the H+-ATPase inhibitory activity of BE-54017 (20), close structural relatives of indolotryptolines, including tryptoline-based (21), indolo-β-carboline (fascaplysin)-based (22), and indolocarbazole-based (4) compounds, have all been explored as protein kinase inhibitors. The final products of the two bor biosynthetic pathway branches, borregomycin A (1) and B (2), were therefore tested for inhibitory activity against a panel of 59 diverse disease-relevant kinases (KinaseProfiler; Millipore). Borregomycin B did not exhibit an IC50 of less than 10 μM against any kinases in the panel. At 10 μM, the most inhibited kinases PRAK, IGF-1R, and PI3KCδ showed residual activities of 66%, 67%, and 69%, respectively (Fig. S8). At the same concentration, borregomycin A exhibited a sub–10-μM IC50 against a single kinase, CaMKI (Fig. 6). When borregomycin A was assayed against a more extensive panel of CaMKI-related kinases, it most strongly inhibited the CaMKIIδ kinase (IC50: 3.4 μM; Fig. S8). Elevated levels of CaMKII, which is a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent serine/threonine kinase that is involved in various signal transduction pathways, have been implicated in diseases such as heart failure (23) and cancer (24). As borregomycin A is active at comparably low micromolar levels against both HCT116 cells and CaMKIIδ in vitro, the inhibition of CaMKIIδ may be a key contributing factor to its in vitro cytotoxicity.

Fig. 6.

KinaseProfiler results. Residual protein kinase activity in the presence of 10 μM borregomycin A is shown for a diverse set of disease-relevant kinases (n = 2).

Fascaplysin, a simple indolo-β-carboline, inhibits Cdk4-D1 kinase; however, its planar structure also renders it a DNA intercalator (25). This has inspired the synthesis of nonplanar fascaplysin analogs in an attempt to eliminate the DNA intercalating property, thereby reducing its toxicity to normal cells (26). Similarly, the planar borregomycin B appears to be a general cytotoxin, whereas borregomycin A, which is rendered nonplanar by BorX2-catalyzed indole rearrangement followed by BorX3-catalyzed oxidation, appears to show more specificity in both the cell-based cytotoxicity assay and the kinase activity assay. The observed kinase inhibitory activity of borregomycin A suggests that oxidized indolotryptolines may warrant further investigation as potential lead structures for the development of novel protein kinase inhibitors.

Conclusions

Previous applications of homology-directed metagenomic library screening include the characterization of gene clusters encoding known compounds (27), the generation of nonnatural glycopeptide congeners through the expression of novel tailoring enzymes (28), and the heterologous production of ribosomal peptides that were found at low levels in environmental samples (29). Unique from these previous reports, this study successfully uses homology-directed metagenomic library screening to target, isolate, and heterologously express a biosynthetic gene cluster that encodes for a new member of a specific underexplored family of natural products. Iterations of this approach using DNA isolated from other environments should allow for further expansion of the structural diversity seen in the indolotryptoline family of tryptophan dimers. The general strategy of phylogenetically profiling degenerate PCR-derived amplicons to guide gene cluster selection and transcription factor overexpression to activate recovered gene clusters of interest can easily be adapted to the discovery of new members of other previously rare families of bioactive natural products from large metagenomic libraries. As traditional natural product discovery methods saturate the chemical space of frequently occurring bacterial secondary metabolites, homology-guided metagenomic library screening should be useful for the routine discovery of novel natural products that expand on previously underexplored bioactive natural product families.

Methods

Soil eDNA Library Construction.

A library consisting of in excess of 10 million unique cosmid clones was constructed using DNA isolated from Anza-Borrego Desert (CA) soil, following published methods (30). Briefly, soil was resuspended in lysis buffer [100 mM Tris⋅HCl, 100 mM sodium EDTA, 1.5 M sodium chloride, 1% (wt/vol) cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, pH 8.0] and heated for 2 h at 70 °C. The soil was removed by centrifugation (30 min, 4,000 × g, 4 °C). eDNA was precipitated from the supernatant by adding 0.7 vol isopropanol and then collected by centrifugation (30 min, 4,000 × g, 4 °C). High molecular weight eDNA (≥25 kb) was purified from the resulting pellet by gel electrophoresis (1% agarose, 16 h, 20 V) and recovered by electroelution (2 h, 100 V). Purified eDNA was concentrated (100-kDa molecular weight cutoff), blunt-ended (End-It; Epicentre), ligated into the SmaI site of pWEB or pWEB-TNC (Epicentre), packed into λ-phage, transfected into E. coli EC100 (Epicentre), and selected using LB containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin. The resulting eDNA library was archived as a total of 2,176 unique sublibraries containing 4,000–5,000 clones each. Matching DNA miniprep and glycerol stock pairs were generated for each sublibrary. DNA minipreps were arrayed such that sets of 8 sublibraries were combined to generate 272 unique “rows”.

Homology-Guided Screening for Indolotryptoline Gene Clusters.

A degenerate PCR primer set (StaDlikeF, ATGVTSCAGTACCTSTACGC; StaDlikeR, YTCVAGCTGRTAGYCSGGRTG) was designed on the basis of conserved regions found in all known staD-like oxy-tryptophan dimerization genes (accession nos.: vioB, AF172851.1; staD, AB088119.1; inkD, DQ399653.1; rebD, AJ414559.1; atD, DQ297453.1; abeD, JF439215.1; and claD, JN165773.1). The eDNA library was screened by conducting degenerate PCR on DNA from each of the 272 pooled miniprep rows, using standard Taq polymerase reaction conditions (New England Biolabs). PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 95 °C for 5 min; 7 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 65 °C for 30 s with 1 °C decrement per cycle to 59 °C, and 72 °C for 40 s; 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 40 s; 1 cycle of 72 °C for 7 min; and 4 °C hold. Amplicons of the correct predicted size (561 bp) were gel purified, reamplified, and sequenced using the degenerate primers. A ClustalW (MacVector) phylogenetic tree was constructed by aligning the library amplicon sequences with the corresponding region from known oxy-tryptophan dimerization genes. One sequence from well 1091 (Fig. S9) was found to fall in the abe/cla clade.

Recovery of Pathway Harboring Clone from eDNA Library.

A PCR primer set designed to specifically recognize the 1091 amplicon (1091F, GGAGCAGTTGCAGCTGGC; 1091R, CGCATGAACAGGTGGTGC) was used to recover the eDNA cosmid clone containing this tryptophan dimerization gene from the 1091 sublibrary, using a serial dilution strategy. Initially the 1091 glycerol stock was resuspended in LB to an OD600 of 0.5, diluted 2 × 10−5-fold, and arrayed as 60-μL aliquots (∼25 cells) into four sterile 96-well plates. The plates were grown overnight and screened by whole-cell PCR to identify specific wells containing the clone of interest. The culture broth in the PCR-positive wells was then spread on LB plates and individual colonies were screened by colony PCR to identify the specific clone harboring the 1091 amplicon sequence. This clone, AB1091, was de novo sequenced at the Sloan Kettering Institute DNA Sequencing Core Facility (New York), using 454 pyrosequencing technology (Roche). AB1091 was then annotated using FGENESB (Softberry) for gene prediction and BLASTP (National Center for Biotechnology Information) for protein homology searches (Fig. S9).

Retrofitting and Conjugation of bor Gene Cluster-Containing Clone into S. albus.

AB1091, the cosmid containing the bor pathway, was digested with AanI and ligated with the 6.8-kb DraI fragment from the E. coli/Streptomyces shuttle vector pOJ436. This fragment contains the origin of transfer (oriT), the apramycin resistance marker, and the Streptomyces φC31 integration system (31). The retrofitted AB1091 was transformed into S. albus by conjugation with E. coli S17.1, using published methods (31). Exconjugants were selected on mannitol soy flour medium (MS), using an apramycin (25 μg/mL) and naladixic acid (25 μg/mL) overlay. Successful exconjugants were restruck on MS plates and grown for an additional 5 d before harvesting spores.

BorR Expression.

BorR was PCR amplified from AB1091, using Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs) and the following primer pair: BorRF, GAGACATATGAAGACTCTGCCGGGTCG; BorRR, GAGATTAATTAACTACCGCGCTTCTCGGAG (NdeI and PacI sites added for cloning are shown in italics). PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 98 °C for 1 min; 40 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 63 °C for 25 s, and 72 °C for 1 min 30 s; 1 cycle of 72 °C for 7 min; and 4 °C hold. NdeI/PacI-digested PCR product was cloned into NdeI/PacI-digested pIJ10257 (32). This construct was then moved by conjugation into S. albus harboring the bor pathway and resulting exconjugants were selected using hygromycin (100 μg/mL). Successful exconjugants were restruck on MS plates and grown for an additional 5 d before harvesting spores.

Borregomycin Production and Isolation.

S. albus AB1091 spore stocks (both with and without the pIJ10257 borR expression construct) were used to inoculate 50-mL aliquots of R5A media (11) in 200-mL baffled flasks (10 L total). After 12 d (30 °C, 200 rpm, 25 mm diameter orbit, Infors Multitron II shaker, Switzerland) the cultures were pooled and extracted with 2 vol of ethyl acetate. The resulting crude extract was dried in vacuo; dissolved in 90:10 methanol:water; and then partitioned with hexanes, methylene chloride, and ethyl acetate, using a modified Kupchan scheme (33). The methylene chloride fraction was separated by silica gel RediSep flash chromatography (RediSepRf 12 g silica flash column: 5 min 100% hexane, 35 min linear gradient from 100% hexane to 100% ethyl acetate, and 5 min of 100% ethyl acetate). Compounds 1 and 6 coeluted with the 75:25 hexanes:ethyl acetate fraction, 2 eluted with the 70:30 hexanes:ethyl acetate fraction, 3 eluted with the 65:35 hexanes:ethyl acetate fraction, 4 eluted with the 60:40 hexanes:ethyl acetate fraction, and 5 eluted with the 10:90 hexanes:ethyl acetate fraction. Compounds were purified from these fractions, using isocratic reversed-phase HPLC (XBridge C18, 150 × 10 mm, 5 μm). Compounds 1 (0.7 mg) and 6 (0.7 mg) were separated from each other using 62:38 methanol:water. Compound 2 (1.4 mg) was purified using 65:35 methanol:water. Compound 3 (1.8 mg) was purified using 57:43 methanol:water. Compound 4 (0.6 mg) was purified using 50:50 methanol:water. Compound 5 (0.5 mg) was purified using 52:48 methanol:water. Analytical liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) data were recorded on a Micromass ZQ instrument (Waters). NMR data were obtained using a 600-MHz spectrometer (Bruker). High resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data were acquired using an LCT Premier XE mass spectrometer (Waters) at the Sloan Kettering Institute Analytical Core Facility and an LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) at the Rockefeller University Proteomics Resource Center. Specific rotation was measured using a P-1020 Polarimeter (Jasco).

Bioactivity Assays.

For cytotoxicity assays against bacteria and yeast, overnight cultures (37 °C, 200 rpm, 25 mm diameter orbit, Infors Multitron II shaker, Switzerland) were diluted 10−6-fold and arrayed as 100-μL aliquots into sterile 96-well microtiter plates. An ampicillin control and compounds 1–6 resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide were added at an initial concentration of 25 μg/mL and serially diluted 2-fold across the plate such that the final concentrations were 25, 13, 6.3, 3.1, 1.6, 0.78, 0.39, 0.20, 0.098, 0.049, 0.024, and 0.012 μg/mL. A dimethyl sulfoxide control was similarly diluted across one row of the plate. Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. The lowest concentration with no observable growth (OD < 0.05) is reported as the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for each metabolite.

For the cytotoxicity assay against human colon tumor cell line HCT116 (ATCC; CCL-247), the cells were grown in McCoy’s 5A Modified Media (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS and 1% (vol/vol) penicillin/streptomycin (37 °C with 5% CO2). Cells were seeded as 100-μL aliquots into sterile 96-well plates at ∼1,000 cells per plate and incubated for 24 h before adding compounds. A dimethyl sulfoxide control and compounds 1–6 resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide were dissolved in fresh media and added to the cells at final concentrations of 50, 25, 13, 6.3, 3.1, 1.6, 0.78, 0.39, 0.20, 0.098, 0.049, and 0.024 μg/mL and grown for an additional 72 h. The cell density in each well was then determined with a crystal violet assay (34). Briefly, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS (10 min, 24 °C). After an additional wash with PBS, the cells were stained with 0.1% (wt/vol) filtered crystal violet solution (30 min, 24 °C), washed with water, and air dried. Ten percent acetic acid was added to the stained cells to extract the dye and the absorbance at 590 nm was measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (Epoch; BioTek). The normalized absorbance values were plotted and curve fitted using Graphpad Prism to determine the IC50s.

Compounds were submitted to EMD Millipore to determine their inhibitory activity against a panel of kinases (KinaseProfiler) and for IC50 (IC50Profiler) measurements. Radiometric and homogenous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF)-based methods were used to measure the incorporation of phosphate into the substrate in the presence of the compound for protein and lipid kinase assays, respectively. The activity values were normalized against readings taken in the absence of any added compound. Please refer to the EMD Millipore website (www.millipore.com) for additional protocol details.

Supporting Information.

Please see SI Text for a detailed description of the structure elucidation arguments and additional analytical data (SI Text), 1H and 13C NMR spectra (Figs. S1–S6), heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) data (Fig. S7), kinase inhibition activity data (Fig. S8), and bor gene cluster annotation data (Fig. S9).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM077516. S.F.B. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Scientist.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database [accession no. JX827455 (clone AB1091)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1218073110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tulp M, Bohlin L. Rediscovery of known natural compounds: Nuisance or goldmine? Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13(17):5274–5282. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan KS, Drennan CL. Divergent pathways in the biosynthesis of bisindole natural products. Chem Biol. 2009;16(4):351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sánchez C, Méndez C, Salas JA. Indolocarbazole natural products: Occurrence, biosynthesis, and biological activity. Nat Prod Rep. 2006;23(6):1007–1045. doi: 10.1039/b601930g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakano H, Omura S. Chemical biology of natural indolocarbazole products: 30 years since the discovery of staurosporine. J Antibiot. 2009;62(1):17–26. doi: 10.1038/ja.2008.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakase K, et al. 2000. Antitumor substance BE-54017 and its production. Patent JP 2000178274.

- 6.Williams DE, et al. Cladoniamides A-G, tryptophan-derived alkaloids produced in culture by Streptomyces uncialis. Org Lett. 2008;10(16):3501–3504. doi: 10.1021/ol801274c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang FY, Brady SF. Cloning and characterization of an environmental DNA-derived gene cluster that encodes the biosynthesis of the antitumor substance BE-54017. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(26):9996–9999. doi: 10.1021/ja2022653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torsvik V, Goksøyr J, Daae FL. High diversity in DNA of soil bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56(3):782–787. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.3.782-787.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onaka H, Taniguchi S, Igarashi Y, Furumai T. Cloning of the staurosporine biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces sp. TP-A0274 and its heterologous expression in Streptomyces lividans. J Antibiot. 2002;55(12):1063–1071. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.55.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan KS. Biosynthetic gene cluster for the cladoniamides, bis-indoles with a rearranged scaffold. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e23694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sánchez C, et al. The biosynthetic gene cluster for the antitumor rebeccamycin: Characterization and generation of indolocarbazole derivatives. Chem Biol. 2002;9(4):519–531. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salas AP, et al. Deciphering the late steps in the biosynthesis of the anti-tumour indolocarbazole staurosporine: Sugar donor substrate flexibility of the StaG glycosyltransferase. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58(1):17–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holden MT, et al. Cryptic carbapenem antibiotic production genes are widespread in Erwinia carotovora: Facile trans activation by the carR transcriptional regulator. Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt 6):1495–1508. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-6-1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biggins JB, Gleber CD, Brady SF. Acyldepsipeptide HDAC inhibitor production induced in Burkholderia thailandensis. Org Lett. 2011;13(6):1536–1539. doi: 10.1021/ol200225v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopwood DA. Genetic contributions to understanding polyketide synthases. Chem Rev. 1997;97(7):2465–2498. doi: 10.1021/cr960034i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarzer D, Finking R, Marahiel MA. Nonribosomal peptides: From genes to products. Nat Prod Rep. 2003;20(3):275–287. doi: 10.1039/b111145k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue Y, Zhao L, Liu HW, Sherman DH. A gene cluster for macrolide antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces venezuelae: Architecture of metabolic diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(21):12111–12116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson MC, Gulder TA, Mahmud T, Moore BS. Shared biosynthesis of the saliniketals and rifamycins in Salinispora arenicola is controlled by the sare1259-encoded cytochrome P450. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(36):12757–12765. doi: 10.1021/ja105891a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bush JA, Long BH, Catino JJ, Bradner WT, Tomita K. Production and biological activity of rebeccamycin, a novel antitumor agent. J Antibiot. 1987;40(5):668–678. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura T, et al. Synthesis and assignment of the absolute configuration of indenotryptoline bisindole alkaloid BE-54017. Org Lett. 2012;14(17):4418–4421. doi: 10.1021/ol3019314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trujillo JI, et al. Novel tetrahydro-beta-carboline-1-carboxylic acids as inhibitors of mitogen activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase 2 (MK-2) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17(16):4657–4663. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soni R, et al. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (Cdk4) by fascaplysin, a marine natural product. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;275(3):877–884. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Backs J, et al. The delta isoform of CaM kinase II is required for pathological cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling after pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(7):2342–2347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813013106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rokhlin OW, et al. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II plays an important role in prostate cancer cell survival. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6(5):732–742. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.5.3975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hörmann A, Chaudhuri B, Fretz H. DNA binding properties of the marine sponge pigment fascaplysin. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9(4):917–921. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00313-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aubry C, et al. New fascaplysin-based CDK4-specific inhibitors: Design, synthesis and biological activity. Chem Commun. 2004;(15):1696–1697. doi: 10.1039/b406076h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piel J. A polyketide synthase-peptide synthetase gene cluster from an uncultured bacterial symbiont of Paederus beetles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(22):14002–14007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222481399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banik JJ, Craig JW, Calle PY, Brady SF. Tailoring enzyme-rich environmental DNA clones: A source of enzymes for generating libraries of unnatural natural products. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(44):15661–15670. doi: 10.1021/ja105825a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donia MS, Ruffner DE, Cao S, Schmidt EW. Accessing the hidden majority of marine natural products through metagenomics. ChemBioChem. 2011;12(8):1230–1236. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brady SF. Construction of soil environmental DNA cosmid libraries and screening for clones that produce biologically active small molecules. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(5):1297–1305. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. Norwich, UK: John Innes Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong HJ, Hutchings MI, Hill LM, Buttner MJ. The role of the novel Fem protein VanK in vancomycin resistance in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(13):13055–13061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kupchan SM, Britton RW, Ziegler MF, Sigel CW. Bruceantin, a new potent antileukemic simaroubolide from Brucea antidysenterica. J Org Chem. 1973;38(1):178–179. doi: 10.1021/jo00941a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zivadinovic D, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Membrane estrogen receptor-alpha levels in MCF-7 breast cancer cells predict cAMP and proliferation responses. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(1):R101–R112. doi: 10.1186/bcr958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.