Abstract

Objective

In developing countries, Helicobacter pylori infection is mainly acquired during childhood and may be a predisposing factor for peptic ulcer or gastric cancer later in life. Noninvasive diagnostic tools are particularly useful in children for screening tests and epidemiological studies. We aimed to determine the prevalence of H. pylori infection among Kurdish children in Sanandaj, West Iran.

Methods

We used a Helicobacter Pylori Stool Antigen (HpSA) test to detect H. pylori infection. A questionnaire was used to collect data about age, sex, duration of breastfeeding, and family size. A total of 458 children aged 4 months to 15 years were enrolled in this study.

Findings

The mean age of enrolled children was 5.6±5.4 years. Stool samples were positive for H. pylori in 294 (64.2%) children. The prevalence of H. pylori infection increased with age (P<0.001). We found a significant increase in the infection rate as the family size grew (P=0.005). There was no correlation between a positive H. pylori status and gender (P=0.6) or the duration of breastfeeding (P=0.8).

Conclusion

It seems that the prevalence of H. pylori infection is very high in children in Sanandaj. It begins at early infancy (before 4th month of age) and cumulatively increases with age.

Keywords: Helicobacter Pylori, Prevalence, Children, Iran

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori colonizes over 50% of people worldwide[1]. Colonization is usually acquired during childhood and is the most common cause of chronic gastritis. It is also associated with duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, gastric adenocarcinoma, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. In developing countries, its prevalence is relatively high. In children, the prevalence of H. pylori ranges from less than 10% to over 80%. The risk factors for H. pylori infection include socioeconomic status, household crowding, ethnicity, migration from high prevalence regions, and infection status of family members.

The aim of this study was to determine some epidemiological aspects of the infection among children in Sanandaj, which is the center of Kurdistan province in west Iran with a population of about 400000.

Subjects and Methods

This cross-sectional population-based study was based on samples of 4-month to 15-year-old children. The children were divided into six age groups (4 months, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 15 years old). Samples were collected from children aged 3-5 months, 10-14 months, 22-26 months, 4.5-5.5 years, 9-11 years, and 14-16 years for each group respectively. The lower age groups were selected randomly from healthy children who referred to primary healthcare centers for vaccination and the older ones were from 12 schools with different socioeconomic status across the city. We used simple random sampling in both lower and upper age groups. There was a list of children in both health care centers and also in schools. We used a computer program to generate random numbers in order to draw a selected group of cases from lists. The sample size calculation was based on at least 30% prevalence rate, 5% precision, and 95% confidence interval, computed from previous epidemiological studies[2–4].

The data were collected in two phases: an interview with the mothers or participating children during April–July 2007, and the screening of the children for H. pylori infection during June–September 2007. All procedures and tests were carefully explained to the parents of patients informed consent was obtained.

The data regarding age, sex, duration of breastfeeding, family size, previous antibiotic usage, and infection status were recorded for each child. No child was tested within a week of taking antibiotics.

A total of 458 stool samples were collected randomly from the children in all six age groups including 4 months, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 15 years old. The Helicobacter stool antigen test was used to detect the infection. Stool antigen test has the sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 93%[5–9]. The stool assay was performed using the DIA.PRO Hp SA test (DIA.PRO, Diagnostic Bioprobes Srl, Milano, Italy). This assay is a microplates-based enzyme immunoassay. Microplates are coated with a cocktail of affinity purified mouse monoclonal antibodies directed to the most specific H. pylori antigens. Stool samples were collected using a kit consisting of a plastic spoon used to scoop a small amount of stool from the toilet paper or bowl into an airtight container. The samples were frozen at a temperature below −20°C as described in the kit until analyses were performed.

In the 1st incubation, the solid phase was treated with the sample, previously extracted from the stools, and simultaneously with a mixture of monoclonal antibodies to H. pylori, conjugated with peroxidase (HRP). After washing out all the other components of the sample, in the 2nd incubation, the bound enzyme specifically presented on the solid phase generated an optical signal. The color developed in the presence of the bound enzyme, which was proportional to the amount of H. pylori antigens present in the sample. Stop solution was added and the results were inspected spectrophotometrically at 450 nm within 15 min of adding the stop solution. A visual determination might also be made within 15 min but we used spectrophotometry in this study to provide reproducible results. Positive and negative controls were built into the test as internal controls.

Internal Quality Control: The controls/calibrator was checked any time the kit was used in order to verify whether the expected optical density at 450nm (OD450nm) or sample OD450nm/Cut-Off value (S/Co) values have been matched in the analysis. The following parameters have been met continuously as recommended in the kit package-insert (Table 1)[10]. Calculations of results were made using both quantitative and qualitative assays.

Table 1.

Requirements for quality control

| Parameter | Requirements |

|---|---|

| Blank well | < 0.100 OD450nm* value |

| CAL ‡ 0 ug/ml | < 0.200 mean OD450nm value after blanking |

| CAL 0.1 ug/ml | OD450nm > OD450nm CAL 0 ug/ml + 0.100 |

| CAL 1 ug/ml | > 1.000 OD450nm value |

OD450nm: Optical Density at 450nm

CAL: Calibrator

Quantitative Assay: The mean OD450nm value of the calibrators was calculated. Then a calibration curve was drawn using a 4 parameters fitting curve system. The concentration of HP antigen in the sample was calculated on the curve.

Qualitative Assay: The test results were calculated by means of a cut-off value determined from the O450nm value of the CAL 0ug/ml (CAL 0) and the OD450nm of the CAL 0.1 ug/ml (CAL 0.1) with the following formula:

Cut-Off = (CAL 0 + CAL 0.1) / 2

Interpretation of results: In the quantitative assay, samples showing a concentration of H. pylori antigen higher than 0.05 ug/ml was considered positive. For the qualitative assay, test results were interpreted as a ratio of the sample OD450nm (S) and the Cut-off value (Co), mathematically S/Co, according to the following rules: S/Co of less than 1.00 was considered negative and means that the child is not infected by H. pylori, S/Co of 1.0–1.1 was considered as undetermined and the child retested on a second sample, and S/Co of greater than 1.1 was considered positive. Samples with undetermined results on retesting were classified as noninfected. The statistical analyses were performed using the Epi info version 3.3.2 and SPSS software (version 12) to estimate crude odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Chi square test was used as appropriate and P value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Findings

The prevalence rates of H. pylori infection based on age and sex are shown in Table 2. The mean age of enrolled children was 5.6±5.4 years.

Table 2.

Prevalence of H. pylori infection in different age groups and sexes

| Age | Total number in each age group | Total positive test in each age group | Number of female patients | Number of female patients with positive test | Number of male patients | Number of male patients with positive test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 months | 78 | 34 (43.6%) | 41 | 18(44%) | 37 | 16 (43%) |

| one year | 73 | 30 (41.1%) | 34 | 17 (50%) | 39 | 13(33%) |

| 2 years | 78 | 52 (66.7%) | 43 | 26 (60%) | 35 | 26(74%) |

| 5 years | 76 | 59 (77.6%) | 40 | 29 (72%) | 36 | 30 (83%) |

| 10 years | 73 | 47 (64.4%) | 29 | 18 (62%) | 44 | 29 (66%) |

| 15 years | 80 | 72 (90%) | 40 | 35 (87.5%) | 40 | 37 (92.5%) |

| Total | 458 | 294 (64.2%) | 227 | 143 (63%) | 231 | 151 (65%) |

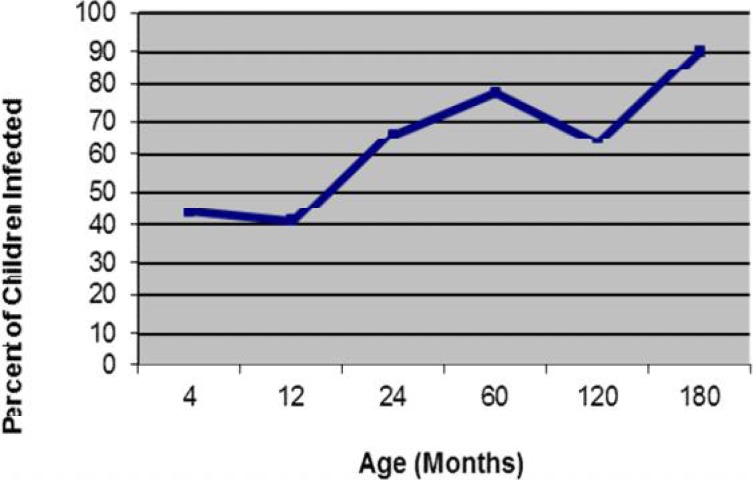

There were increasing prevalence rates of H. pylori infection with increasing age in all age groups (χ2=98.81, P<0.001) with a transient decrease in one and 10-year-old groups (Fig. 1). There were no significant differences between sexes in prevalence of H. pylori infection within each group nor between groups (P=0.6, χ2=0.28, Odds ratio = 1.1, 95%CI [0.76 < OR < 1.63]).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of H. pylori by age group

Table 3 shows the prevalence of H pylori infection based on family size. We found a significant increase in infection rate as the family size grew (P=0.005, χ2=10.55). In order to study the epidemiological effect of breastfeeding on H. pylori infection, we investigated the rate of H. pylori infection and the duration of breastfeeding in 1- to 15-year-old children (Table 4). There was no significant decrease in infection rate as the duration of breastfeeding increased (P=0.8).

Table 3.

Prevalence of H. pylori infection based on family size

| Family size | Infection rate | Number of children in each group |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 67 (53.2%) | 126 |

| 4 | 90 (64.7%) | 139 |

| ≥5 | 137 (71%) | 193 |

| total | 294 (64.2%) | 458 |

(P=0.005, χ2=10.55)

Table 4.

Prevalence of H. pylori Infection based on duration of breastfeeding in children aged 1-15 years

| Duration of breastfeeding | Number (percent) of children | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infected | Non-infected | ||

| No breast feeding | 13 (76%) | 4 (24%) | 17 |

| <6 months | 6 (67%) | 3 (33%) | 9 |

| ≥6 months | 241 (68%) | 113 (34%) | 354 |

| Total | 260 (68%) | 120 (32%) | 380 |

χ2=0.54 P= 0.8

Discussion

We found widespread H. pylori infection in children in our community. Infection with H. pylori is acquired in as early as 4 months of age and even earlier. At 4 months of age at least 43% of children were positive for H. pylori antigen. By 2 years of age 66.7% of children were positive for H. pylori antigen. Approximately 64.2% of all children were infected before they were teens. Infection rate is cumulative with increasing age and maximize at upper age group of 15 years old.

There are significant differences in the prevalence of infection worldwide and even in various parts of any specific country, which is closely related to socioeconomic status and overcrowding. In developing countries, the prevalence rate is high. The prevalence increases generally with age, but decreases have been noted in narrow age ranges in childhood[4, 11–13].

There are many reports of the declining prevalence of H. pylori over brief intervals in childhood[14–17]. Spontaneous elimination of H. pylori infection may be the reason of the declining prevalence in 10 years age group[14, 18–20]. Other explanations are better attention to health issues in older children or use of antibiotics for other infectious diseases [21–25], differences in types of H. pylori in adults in comparison with children, and differences in special gastric receptors[26]. However, these cannot explain second peak of prevalence in 15 years age group.

There are few reports about the prevalence rates of H. pylori infection in different age groups of Iranian children[2–3]. Most of these earlier studies had been done on considerably wide ranges of age groups, and did not include children younger than 1–2 years old.

The age dependent acquisition of H. pylori antigen determined in our study is consistent with previous studies from developing countries[4, 12, 17]. Some reports from developing countries show that most infants have high infection rate early in their life, which can reach 50% by 2 years of age[4, 14, 23].

We found no statistical difference between the rates of prevalence in male and female populations. This is consistent with the results of most other studies[4, 23]. The effects of family size on the prevalence of helicobacter were investigated in several studies[14, 27–29]. Many environmental factors are related to an increased prevalence of infection, but the most powerful one has been the number of children residing in the house. In our study, the difference in the prevalence rate of infection between small families in comparison with larger families (Table 2) was statistically significant.

Since the children were selected randomly, the number of children in the non-breastfed group was very low to evaluate the protective effect of breastfeeding on H. pylori infection more efficiently. The duration of breastfeeding did not have a statistically consistent effect on the rate of infection. The presence of many risk factors for H. pylori infection in the community leading to high rates of infection probably obscured the protective effects of breastfeeding, if any, on H. pylori infection. A more selective study is needed to investigate the protective effects of breastfeeding on H. pylori infection in our country as described in previous reports from other regions[30].

Many studies indicate that stool antigen test is a sensitive and specific mean to diagnose H. pylori infection[31–33]. In 2000, a consensus report[34] stated that two non-invasive tests, urea breath test and stool antigen test, could be used both safely and cost effectively to screen patients (below the age of 45) who were positive for H. pylori without alarming symptoms: “Non-invasive tests are useful for primary diagnosis, when a treatment indication already exists, or to monitor treatment success or failure”[34].

Few recent studies denote lesser sensitivity for some commercial kits[33, 35]. Sensitivity for three commercial kits (Premier Platinum Hp SA, FemtoLab Cnx, and Dia. Pro Hp Ag) was reported to be 63.6%, 88.0%, 56.0% respectively. However, the specificity was high for all tests (reported 97.6% for Dia. Pro Hp Ag). Recently, a systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that the monoclonal technique had a higher sensitivity than the polyclonal one[5]. HpSA assay has been proven to be a highly reliable and simple to use test for the diagnosis of H. pylori. This has been recently re-emphasized by experts[36].

Conclusion

The prevalence of H. pylori infection in children is very high in Sanandaj, beginning at early infancy (before 4 months of age) and is cumulative with increasing age.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of Dr Adibeh Hosseininasab, and all the field co-workers whose assistance made this study possible. Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences supported the whole study.

Conflict of Interest

None

References

- 1.Mitchel HM. In: Epidemiology of infections. 1st ed. Mobley Harry LT, Mendes GL, Hazel SL, editors. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alborzi A, Soltani J, Pourabbas B, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children (south of Iran) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;54(4):259–61. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falsafi T, Valizadeh N, Sepehr S, et al. Application of a stool antigen test to evaluate the incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents from Tehran, Iran. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12(9):1094–7. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1094-1097.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres J, Perez-Perez G, Goodman KJ, et al. A comprehensive review of the natural history of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Arch Med Res. 2000;31(5):431–69. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(00)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gisbert JP, de la Morena F, Abraira V. Accuracy of monoclonal stool antigen test for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(8):1921–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gisbert JP, Pajares JM. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection by stool antigen determination: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2829–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gisbert JP, Pajares JM. Stool antigen test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection: a systematic review. Helicobacter. 2004;9(4):347–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaira D, Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, et al. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection with a new non-invasive antigen-based assay. HpSA European study group. Lancet. 1999;354(9172):30–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)08103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Doorn OJ, Bosman DK, van't Hoff BW, et al. Helicobacter pylori Stool Antigen test: a reliable non-invasive test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13(9):1061–5. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diagnostic Bioprobes Srl. Sesto San Giovanni (MI), Italy: DIA.PRO Company; 2011. Enzyme Immunoassay for the qualitative/ quantitative determination of Helicobacter pylori Antigen in human stools; pp. 1–8. Available at: http://www.diapro.it/dmdocuments/hpag.ce-insert-rev.1-0811-eng.pdf. Access date: Oct 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha SK, Martin B, Gold BD, et al. The incidence of Helicobacter pylori acquisition in children of a Canadian First Nations community and the potential for parent-to-child transmission. Helicobacter. 2004;9(1):59–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pounder R, Ng D. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in different countries. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(2):33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham DY, Malaty HM, Evans DG, et al. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in an asymptomatic population in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1991;100(1495):501. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90644-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redlinger T, O'Rourke K, Goodman KJ. Age distribution of Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence among young children in a United States/Mexico border community: evidence for transitory infection. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(3):225–30. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindkvist P, Asrat D, Nilsson I, et al. Age at acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection: comparison of a high and a low prevalence country. Scand J Infec Dis. 1996;28(2):181–4. doi: 10.3109/00365549609049072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blecker U, Hauser B, Lanciers S, et al. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori-positive serology in asymptomatic children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;16(3):252. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahalanabis D, Rahman MM, Sarker SA, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in the young in Bangladesh: prevalence, socioeconomic and nutritional aspects. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25(4):894–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.4.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothenbacher D, Bode G, Brenner H. Dynamics of Helicobacter pylori infection in early childhood in a high-risk group living in Germany: loss of infection higher than acquisition. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(9):1663–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perri F, Pastore M, Clemente R, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection may undergo spontaneous eradication in children: a 2-year follow-up study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27(2):181–3. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199808000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia H, Talley N. Natural acquisition and spontaneous elimination of Helicobacter pylori infection: clinical implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(10):1780–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hestvik E, Tylleskar T, Kaddu-Mulindwa D, et al. Helicobacter pylori in apparently healthy children aged 0-12 years in urban Kampala, Uganda: a community-based cross sectional survey. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortiz D, Cavazza ME, Rodríguez O, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Warao lineage communities of Delta Amacuro State, Venezuela. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98(6):721–5. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000600002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malaty HM, El-Kasabany A, Graham DY, et al. Age at acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection: a follow-up study from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2002;359(9310):931–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08025-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malaty HM, Graham DY, Wattigney WA, et al. Natural history of Helicobacter pylori infection in childhood: 12-year follow-up cohort study in a biracial community. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28(2):279–82. doi: 10.1086/515105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broussard CS, Goodman KJ, Phillips CV, et al. Antibiotics taken for other illnesses and spontaneous clearance of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(8):722–9. doi: 10.1002/pds.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Granström M, Tindberg Y, Blennow M. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in a cohort of children monitored from 6 months to 11 years of age. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(2):468–70. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.468-470.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodman KJ, Correa P, Aux HJT, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in the Colombian Andes: A population-based study of transmission pathways. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(3):290–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos IS, Boccio J, Santos AS, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and associated factors among adults in Southern Brazil: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueda M, Kikuchi S, Kasugai T, et al. Helicobacter pylori risk associated with childhood home environment. Cancer Sci. 2003;94(10):914–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01375.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okuda M, Miyashiro E, Koike M, et al. Breast-feeding prevents Helicobacter pylori infection in early childhood. Pediatr Int. 2001;43(6):714–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2001.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato S, Ozawa K, Okuda M, et al. Accuracy of the stool antigen test for the diagnosis of childhood Helicobacter pylori infection: a multicenter Japanese study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):296–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konstantopoulos N, Russmann H, Tasch C, et al. Evaluation of the Helicobacter pylori stool antigen test (HpSA) for detection of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(3):677–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Megraud F. Comparison of non-invasive tests to detect Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents: results of a multicenter European study. J Pediatr. 2005;146(2):198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht 2-2000 Consensus Report. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(2):167–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrews J, Marsden B, Brown D, et al. Comparison of three stool antigen tests for Helicobacter pylori detection. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56(10):769–71. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.10.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection - The Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56(6):772–81. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]