Abstract

Background

Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome(NBS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder with specific clinical features, characteristic chromosomal breakage and combined imunodeficiency. Patients with this condition also associate growth retardation with microcephaly, predisposition to malignancy and specific skin manifestations.

Case Presentation

Here we report a 3-year old girl known with NBS associated with cutaneous sarcoid-like lesions. She presented with one year history of squamous lesions on the face and upper and lower limbs. The lesions were biopsied and histopatological examination revealed nonnecrotizing epitheloid granulomas and raised the suspicion of a sarcoid-like entity.

Conclusion

The interest of this case will serve to better understand clinical manifestations in a rare genetic entity. Close follow-up is advised as cutaneous granulomas may be the first manifestation of systemic granulomas.

Keywords: Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome, Sarcoid-like Lesion, Granulomas, Imunodeficiency

Introduction

Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome (NBS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder, belonging to chromosomal instability syndromes, characterized by specific facial features, growth retardation and combined immunodeficiency. The facial features include microcephaly, forehead with prominent midface, epichanthus, large ears and sparse hair. Common cutaneous manifestations are telangiectasias, cafe-au-lait spots and vitiligo. These patients may also have photosensitivity[1]. The immunodeficiency is linked to respiratory and urinary recurrent infections, chromosomal instability with spontaneous breakage and predisposition to malignancy[2]. The chromosomal pattern is given by mutation of the NBS-1 gene located on the chromosome 8q21. This gene encodes a protein involved in the DNA damage repair[3]. We report a patient with NBS presenting cutaneous sarcoid-like granulomas.

Case Presentation

A 3-year-old girl known with NBS presented with one year history of squamous lesions on the face and the upper and lower limbs. Without any improvement in the past year, there was an increase in the number of lesions in the last months.

The patient has been known with NBS since she was 2 years old (diagnosis made in another service). The suspicion of NBS was raised immediately after birth based on her facial dysmorphology and clinical features, but the genetic confirmation appeared later after (Fig 1).

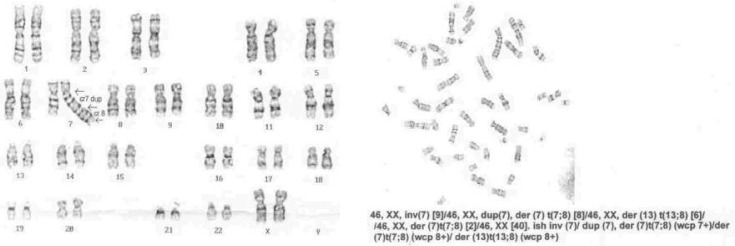

Fig. 1.

The genetic pattern showing chromosomal instability

On the physical examination the patient presented microcephaly with forehead and prominent midface, bilateral epichanthus, large ears and sparse hair (Fig. 2A). We also examined the skin lesions, which were in a large number disseminated over the face and extremities (Fig. 2BC). The dermatological consult revealed numerous squamous plaques localized on the face and extremities, in different evolution states. They were erythematous at the beginning, in evolution crusts appeared on the lesion's surface. The dermatologist suggested the biopsy of the lesions. The histopathological examination revealed sarcoid-like granulomas (Figs. 3, 4). An immunological study was made: the immunoglobulins A, M were normal for the age, with a hypogammaglobulinemia.

Fig. 2.

A) Facial features in Nijmegen Breakage syndrome, B,C) Characteristic cutaneous manifestations with hyperkeratosis only on upper and lower limbs

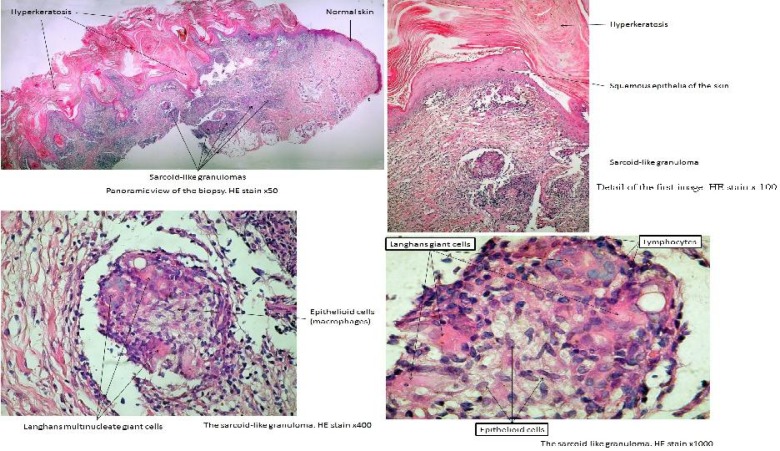

Fig. 3.

The histopathological aspect of cutaneous lessions

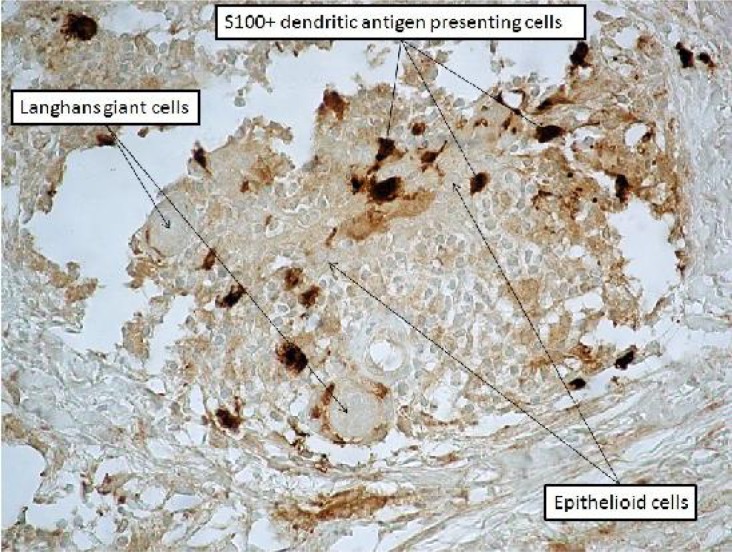

Fig. 4.

The sarcoid-like granuloma. S100 stain × 400

Discussion

NBS is a rare chromosomal breakage syndrome which displays many overlapping features with other clinical entities such as: ataxia-telangiectasia, Bloom syndrome and Fanconi anemia[4]. Generally, karyotypes of the patients with NBS are normal (46,XX or 46,XY). However, in a high proportion of them, spontaneous structural chromosomal rearrangements are observed, as well as other aberrations such as chromatid and/or chromosome breaks and acentric fragments. Most of these rearrangements specifically involve chromosomes 7 and 14, with breakpoints at bands 7p13, 7q35, 14q11, and 14q32, which are identical to those found in persons with ataxia-telangiectasia.

The product of NBS-1 gene is a protein, the nibrin that forms a complex with two cytoplasmic proteins. This complex needs phosphorylation by a protein kinase to be activated. This protein kinase is mutated in ataxia-telangiectasia[5]. This is the molecular proof of the interrelation between NBS and ataxia-telangiectasia, and likely accounts for the relative homogeneity of clinical manifestations. Therefore, NBS is also known as an ataxia-telangiectasia variant 1[6].

The granulomatous reaction pattern, described as an inflammatory reaction, may appear in persons with genetic or acquired immunodeficiency disorders (Table 1). Cutaneous granulomas have occasionally been reported to be a presenting sign of an immunodeficiency disorder[7]. Clinically cutaneous granulomas manifest as erythematous plaques, nodules or papules. The lesions are often scaly, atrophic and ulcerated. The distribution of the lesions is most likely on the face and extremities as in our case. Spontaneous regression has been described[8]. However, they can also be progressive as we have illustrated.

Table 1.

Immunodeficiency disorders associated cutaneous granulomas

| Chronic granulomatous disease |

| X-linked hypogammaglobulinemia |

| Common variable immunodeficiency |

| Ataxia-telangiectasia |

| Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome |

| Severe combined immunodeficiency |

| Primary acquired hypogammaglobulinemia |

Variable histological patterns may be described in cutaneous granulomas: non-necrotizing epitheloid granulomas (sarcoid-like), caseating (tuberculoid) granulomas and necrobiotic granulomas. Granuloma formation in patients with primary immunodeficiency is not yet elucidated.

The possibilities may include: functional imbalance of cellular immunity, diminution of humoral immunity and/or interleukin-2 deficiency.

Clinical manifestations such as cutaneous squamous lesions, and as histopathological being sarcoid-like granulomas have been well described in ataxia-telangiectasia and other primary immunodeficiency disorders[9].

The main difference between sarcoidal granulomas and those from primary immunodefiency is that the last ones have a much lower CD4+ CD8+ T-cell ratio. Patients with primary immunodeficiency usually have hypogammaglobulinemia, meanwhile sarcoidosis is associated with hypergammaglobulinemia. Granuloma formation in primary immunodeficiency disorders may involve the lungs, spleen, liver, joints and skin. The isolated cutaneous involvement is very rare[10].

Cutaneous sarcoid-like granulomas have been recently reported in patients with NBS[11]. Based on the normal control breakage data in granulomatous inflammatory disease in patients without Nijmegen, in NBS granulomas may occur due to the chromosomal repair dysfunctions. Granulomas from primary immunodeficiencies may resemble those from sarcoidosis, because of the clinical and histological similarity[12, 13]. Sarcoidal granulomas are discrete, round to oval, are composed of epitheloid histiocytes and multinucleate giant Langhans cells. Although the granulomas may be in close proximity to one another, their confluence is not commonly found[14]. Because of the aspects described above, many early reports of granuloma formation in patients with primary immunodeficiency were classified as sarcoidosis.

The treatment for cutaneous granulomas may not be necessary in very limited disease, but an important issue is to establish the medication responsible for the improvement of the skin manifestations. Methotrexate and dexamethasone are known to suppress granuloma formation[15]. The cyclophosphamide has been used in the treatment of refractory noninfectious granulomas[16].

Close follow-up is strongly suggested as cutaneous granulomas may be the first manifestation of systemic granulomas.

Conclusion

We believe this case will serve to better understand clinical manifestations in this rare genetic syndrome. It would be interesting to perform chromosomal pattern in each patient with cutaneous granulomas as well as skin biopsies that can elucidate the pathogenetic processes that trigger this noninfectious granuloma formation.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to colleagues in the Medical Genetic Department of Lisboa Children's Hospital for the genetic proof of NBS.

Conflict of Interest

This article has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.The International Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome Study Group. Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2000;82(5):400–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.82.5.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf EK, Shwayder TA. Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome associated with porokeratosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26(1):106–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tauchi H, Matsuura S, Kobayashi J, et al. Nijmegen breakage syndrome, NBS1, and molecular links to factors for genomic instability. Oncogene. 2002;21(58):8967–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gennery AR, Slatter MA, Bhattacharya A, et al. The clinical and biological overlap between Nijmegen breakage syndrome and Fanconi anemia. Clin Immunol. 2004;113(2):214–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uziel T, Lerenthal Y, Moyal L, et al. Requirement of the MRN complex for ATM activation by DNA damage. EMBO J. 2003;22(20):5612–21. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wegner RD, Chrzanowska KH, Sperling K, Stumm M. Ataxia-telangiectasia variants (Nijmegen breakage syndrome) In: Ochs HD, Smith CIE, Puck JM, editors. Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases, a Molecular and Genetic Approach. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 324–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbisier A, Eschard C, Motte J, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous lesions disclosing ataxia telangiectasia. Ann Dermatol Venerol. 1999;126(8-9):608–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez-Cuesta C, Molinos L, Cascante JA, et al. Cutaneous granulomas in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency. Acta Derm Venerol. 1999;79(4):334. doi: 10.1080/000155599750010869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drolet BA, Drolet B, Zvulunov A, et al. Cutaneous granulomas as a presenting sign in ataxia-telangiectasia. Dermatology. 1997;194(3):273–5. doi: 10.1159/000246117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitra A, Pollock B, Gooi J, et al. Cutaneous granulomas associated with primary immunodeficiency disorders. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):194–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoo J, Wolgamot G, Torgerson TR, et al. Cutaneous noncaseating granulomas associated with Nijmegen breakage syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(3):418–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lun KR, Wood DJ, Muir JB, et al. Granulomas common variable immunodeficiency: a diagnostic dilemma. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(1):51–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2004.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Jager M, Blokx W, Warris A, et al. Immunohistochemical features of cutaneous granulomas in primary immunodeficiency disorders: a comparison with cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(5):467–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weedon D. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 3rd Ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2010. The granulomatous reaction pattern; pp. 170–94. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badgwell C, Rosen T. Cutaneous sarcoidosis therapy updated. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(1):69–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doty JD, Mazur JE, Judson MA. Treatment of corticosteroid-resistant neurosarcoidosis with a short-course cyclophosphamide regimen. Chest. 2003;124(5):2023–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]