Abstract

The ability to communicate to others and express ourselves is a basic human need. As we develop our understanding of the world, based on our upbringing, education and so on, our perspective and the way we communicate can differ from those around us. Engaging and interacting with others is a critical part of healthy living. It is the responsibility of the individual to ensure that they are understood in the way they intended.

Shared language refers to people developing understanding amongst themselves based on language (e.g. spoken, text) to help them communicate more effectively. The key to understanding language is to first notice and be mindful of your language. Developing a shared language is an ongoing process that requires intention and time, which results in better understanding.

Shared language is critical to collaboration, and collaboration is critical to business and education. With whom and how many people do you connect? Your 'shared language' makes a difference in the world. So, how do we successfully do this? This paper shares several strategies.

Your sphere of influence will carry forward what and how you are communicating. Developing and nurturing a shared language is an essential element to enhance communication and collaboration whether it is simply between partners or across the larger community of business and customers. Constant awareness and education is required to maintain the shared language. We are living in an increasingly smaller global community. Business is built on relationships. If you invest in developing shared language, your relationships and your business will thrive.

Keywords: Language, communication, creativity, design coaching, empathy

Introduction

Communication and the ability to express ourselves satisfy one of our most basic human needs. We engage and communicate with several people throughout our typical day. Commonly we assume that others hold similar values, beliefs and aspirations as our own. Any deviation from our own views may seem strange, unreasonable and ‘wrong’. As dynamic individuals dealing with equally dynamic ‘others’, our daily experiences shape our perceptions and develop our perspectives throughout our lives. The language we use and our ability to share language with others impact these perceptions and perspectives, and ultimately impacts upon our effectiveness as entrepreneurs, educators, collaborators, etc. Removing that ability or diminishing it in some way can seriously impact how we perceive others and ourselves.

Entrepreneurialism relies upon creative thinking and problem solving, which often involves imagining what does not yet exist. Being able to communicate initial ideas and concepts before a language and terminology has even been developed can become one of the earliest stumbling blocks in communication. The authors work across design, education and business, and within this paper they pull together tools and techniques based within theory and professional practice to help the individual and collaborators communicate more effectively.

First, let us look at some examples of how we observe language, how nationality impacts the English language and how time changes the meaning of language.

What do you think of when you hear the spoken word ‘Elephant’?

When someone speaks the word ‘elephant’, there are at least two possible ways that others will visualise the word in their mind’s eye. Figure 1 illustrates (a) that some will actually ‘see’ the word in text form; while (b) that others ‘see’ the word in visual form, with context, colour and possibly with a narrative attached. This reaction (either text-based or visual) is key. Even if people declare themselves to be less visual, human nature leads us to visually evaluate people we meet. The way a person speaks, their body language, what they are wearing and so on, provides cues to ‘who they are’ and possibly their value system.

Figure 1. Reaction to the spoken word ‘elephant’ (either visual or text) (Oorka / Shutterstock.com).

So you speak English

“England and America are two countries divided by a common language.” George Bernard Shaw

"We have really everything in common with America nowadays except, of course, language." Oscar Wilde

The authors have both American and British backgrounds and frequently discover new words during their daily interactions.1 During the process of teaching and publishing together they have been sensitised to the value of being aware of differences, as miscommunication is often only a word away! Working together as both academicians and designers has provided the opportunity to communicate, check, reflect and develop over time a shared working language that may well be unique to them. Acknowledging their investment in time, willingness to inquire and seek clarification, they enjoy the process of developing a new understanding of the shared language they develop. Table 1 illustrates some typical daily words that can remind them of their linguistic cultural differences.

Table 1: Differences in American English and British English.

| American English | British English | |

|---|---|---|

| Truck | Lorry | |

| Eraser | Rubber | |

| ATM | Cash dispenser | |

| Trash | Rubbish | |

| Zucchini | Courgette | |

| Egg Plant | Aubergine |

In the coverage of the 2012 Olympics in London, the American broadcasting company NBC had a feature spot each day highlighting the differences between American and British English. In most cases, the differences can be viewed with humour; however, if a Brit said to an American “I’m going outside to have a fag,” the American might have a dramatically different image in their ‘mind’s eye’ than the Brit smoking a cigarette. Or ‘crack’ – which can refer to an illegal drug within the American culture, while in Britain, it can refer to a lively discussion. These differences add to the rich tapestry of our similar but clearly different cultures.

Euphemisms and codes

As our understanding of the world is ever changing, so is the language, and more importantly, the meaning behind that language is changing. Dictionaries are not static volumes limited to definitions of what was. People enjoy playing with language and euphemisms are an accurate barometer of changing attitudes.

Keyes2 (p. 58) tells us:

“…verbal evasions put a spotlight on what most concerns human beings at any given time. This is as true today as it was when the Victorians considered legs too titillating to be mentioned by name (limbs was the preferred synonym).”

Euphemisms are found across all aspects of language, from dealing with money to technology. They can be expressions of ‘political correctness’ (a euphemism in itself!) to acronyms. Table 2 gives a few examples:

Table 2: Euphemisms and codes.

| Euphemism or code | Definition |

|---|---|

| Bread, dough, scratch moolah | Money |

| Broke | Insolvent |

| Shoplifting | Inventory shrinkage |

| Foundation garments | Shapeware (Spanx!) |

| PICNIC | Problem in chair not in computer |

| CODE 18 | User’s head is 18” from the (computer) monitor |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats |

| SWAG | Silly (or Scientific) Wild Ass Guess (engineering and business guestimates) |

However, SWAG has a completely different connotation if you have been invited to the Oscars (the ultimate award for the movie industry). There, SWAG refers to a goodie bag of expensive gifts provided by sponsors. Your language is definitely context sensitive!

One of the authors worked in a corporate design department where the team developed an insider’s code that allowed them to respond to people outside their group (executives) in a way that their team-mates would understand you really wanted to roll your eyes in disbelief. When presented with input that had mediocre, questionable, or no value, a team member could reply:

“That’s an idea OR that’s a thought OR Hmmmmm…”

These types of codes are a shared language between members of a group that may appear innocuous to the uniformed, but tell a different story to the collaborators. Likewise, informal gestures, use of words and attached meaning can be so ingrained in a culture that they are almost invisible to that culture.

The key to understanding language is to first NOTICE and be mindful of your language.

As design and entrepreneurship educators, we should recognise that our first-year students have not developed an understanding of the technical language and tools that will be needed for the subject. For a variety of reasons it is easy to forget this, especially when dealing with people that you expect will have some of this basic understanding.

This point was driven home to us in a graduate level design studio at a university in the United States where the majority of the nine students were Asian and European. In a discussion that centred on empathy, the electronic language translators came out.

Empathy = (Mandarin Translation)

Back to English = to sympathise with/sympathy

Although English was the common language that we were communicating through and we expected that we would have a technical shared language within our field of study, it became quickly clear that we could not and more importantly should not make that assumption.

Developing a shared language is an ongoing process that requires intention, time and respect, which results in better understanding.

Methodologies and theory of change

Shared Language

Within the context of this discussion, shared language refers to individuals developing understanding among them based on language (e.g. spoken, text, body language or visuals) in a way that helps them communicate more effectively. This may be simply explaining to another the meaning of a locally used term, or more extensively it may be a level of engagement and interaction that takes months, possibly years to develop.

Collaboration tends to rely on mutual respect, patience, tolerance and a shared goal. Within the process of collaboration, a shared working language should be developed that helps to define and sometimes redefine terms, language and processes to reduce the need for translation. This agreement is helpful in developing a consistent frame of reference for rigorous expectations. A shared, common language provides a focus for all stakeholders.3

It is most effective when created together by the team. Working together to develop common language helps to define clearer goals and ensures that team members have a common understanding which can help to decrease project costs. Specificity helps remove ambiguity. Rather than adjectives that tend to be very broad in their meaning and liable for multiple interpretations, the language has to be very precise to correctly orient the efforts. Developing this language together helps the individual team members to self-validate their contribution, making them feel more valuable.4

Real understanding occurs when the parties are ‘on the same page’. This is particularly important when people come from different disciplines or backgrounds.5 Shared language takes time and effort to develop and nurture. It refers to the active process of establishing an understanding that would not have otherwise been present.6

There are a number of technical fields that currently utilise shared language (such as sciences, medicine, game development). One of the most advance forms of shared language is music where the printed ‘language’ (sheet music) is readable by players of most instruments.

Start with the ‘Why’

While language can be both an opportunity and a challenge, it is important to be clear about why, how and what ways we are using language. Being clear about motives, intended outcomes and willingness to learn through the process of engaging with another person are keys to developing a shared language.

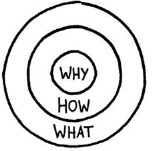

Sinek7 introduces the concept of ‘the Golden Circle’ that has three layers (Why, How and What ) (Figure 2). The inner circle relates to ‘why’ we are motivated to pursue our goals (such as ambitions, philosophy). The middle circle relates to ‘how’ we achieve our goals (such as particular actions) and the outer circle focuses on ‘what’ has been the outcome of the process (such as product, shift in practice). For example, Apple designs, develops and manufactures computers and related devices (the ‘what’). It gives the consumer an intuitive (the ‘how’) means of communication and data storage. But what makes this company so successful in the market place is the ‘why’. The why inspires people to buy-in to your product, belief or practice in the long-term. If something resonates with you in a deeper connection, it builds loyalty and a real shift in behaviour. “People don’t buy What you do, they buy Why you do it. What you do—your products and services— and how you communicate serve as the proof of what you believe”.8 This ‘Golden Circle’ model applies well to the concept of developing a shared language in business communications.

Figure 2. The Golden Circle 7.

1. Why do we need to or equally want to develop a shared language?

“…a new way of understanding language may very well be essential for bringing about more effective and more beneficial ways of relating… and problem solving” 9 (p. 1-3)

In Figure 3, the girl at the centre is presenting a concept to a group of people using spoken language and action. This illustration shows that as we describe one thing, others are possibly ‘seeing’ something different than what we intend to communicate, or are even thinking of something else entirely.

Figure 3. How effective are we when we communicate?

Listening is a linguistic function and is not the same as hearing which is a biologic function. Listening is open to interpretation that is related to the listeners’ moods, emotions, life experience and biology. Frequently, people listen with the intent to respond, or the intent to understand, or the intent to make it wrong. The ‘lens’ through which people ‘look’ at communications is their beliefs – people listen through their beliefs, which may or may not serve them.9

Taking a black and white viewpoint, people frequently confuse facts with assessments. “Assertions have to do with what is so. Assessments have to do with what is possible.”9 (p. 157) Our personal expectation that we have communicated effectively needs to be affirmed through assessment.

Language is not only descriptive, but it is also generative and active. Language is shaping the world as we see it.9 Developing a shared language improves our ability to communicate effectively within our working and personal relationships. This process relies upon mutual compromise, respect, patience and intention (Figure 4). Shared language gets closer to the core meaning of what we are trying to communicate, but to accomplish this, it is important to pay attention to technical, business and design language; culture specific language; regional, national and social differences; and person first language (especially when dealing with people with disabilities).

Figure 4. Elements of a shared language.

As human knowledge has increased, there is a continuous branching into disciplines that use technical or special terminology that is only correctly understood by ‘experts’.10 Additionally, problems are often ambiguous in nature; complex problems cannot be addressed from a single point of view.11

“For years, most design problems could be solved by using a combination of design training, experience and applied intuition. But as the world and its design problems have become more complex, traditional approaches have been less effective.” 12 (p. 6)

We need to develop the habits of shared language because it is critical to collaboration, and collaboration is critical to the success of entrepreneurship and business.

2. How do we successfully develop a shared language?

a. Make things visible

When Steve Jobs arrived at Pixar Studio, the campus was originally planned as three separate buildings that segregated the animators and the computer scientists from everything else. Jobs recognised that this would only reinforce the separate cultures. Instead, to encourage collaboration and incubation he pushed for one giant cavernous space and he insisted there be only two bathrooms in the entire building. He wanted there to be mixing. Human friction makes sparks but you have to force them to mix. The natural tendency for people is to stay isolated, to talk to people who are just like us, who speak our private languages, who understand our problems. By ‘forcing’ people to step out of their private culture and mix, even if it was simply while using the restroom, Jobs encouraged creativity.13

b. Assume that everyone comes to the table with different knowledge, skills and perspectives.

We are unique observers – language is the element that creates the ‘me’ that sees what I see and the ‘you’ who sees what you see.9 What image do you ‘see’ when we say ‘grandmother’? Is it this (Figure 5)?

Figure 5. What do grandmothers look like?(Paassen / Shutterstock.com, Kamira / Shutterstock.com).

Empathic Horizon

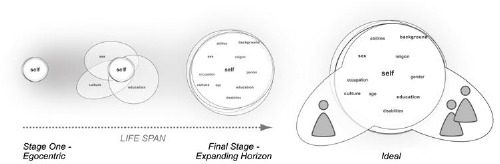

The empathic horizon (Figure 6) refers to the boundary of our personal knowledge. As babies, we were highly dependent on others to respond empathically to our preverbal range of communication – our empathy extended only to our self. As we grew older, we learned to engage with others (e.g. family, community, school) and we slowly become more socially and culturally integrated.14 By acknowledging that we view the world through our own ‘lens’ it is possible to appreciate how we are products of our background, age, education, up-bringing, religion, culture, gender and so on. This becomes increasingly important the further we engage and interact with other people. As we develop as individuals, we become (hopefully) more sensitised to others as we are exposed to other cultures and different approaches to doing things. We must stretch our empathic horizon to accept other peoples’ knowledge, skills and perspectives.

Figure 6. Empathic horizon: Expanding the boundaries of our personal knowledge to engage effectively with others.

c. Acknowledge what is obvious to one person may not be to another.

We assume others think how we think, feel how we feel and judge the way we judge, but this is an inaccurate assumption. To be a different listener means being a different observer, seeing differently and seeing different things. We are necessarily blind to certain possibilities because of our differences.15

Designers carefully observe how consumers engage with products and their material landscape in order to elicit ‘authentic human behaviour’ as it provides rich visual cues and product understanding which leads to innovation. Figure 7 illustrates a recent example of how a person uses technology, compared with the more typical perceived use. In this example of ‘authentic human behaviour’, a person pulls out an iPod to access her calendar in order to confirm a meeting time. From one view she looks relatively well connected and technologically savvy; however, upon further investigation, it is clear that she is using the screen of the iPod differently than intended by the product’s development team and organising her life using post-it notes. This highlights how our behaviour can differ from the next person and represents a learning opportunity for designers, entrepreneurs and business people.

Figure 7. Authentic human behaviour.

d. Look from the point of view of the end user.

In both shared language and business it is critically important to observe and understand from the point of view of the user/customer. In product development, if you make products that no one wants, no one will buy them. If they are phenomenal products that could change the world, but they do not resonate with the people who will use them, the products (physical products, services, protocols, experiences) will be underused, misused, or abandoned. If you develop products that do not work, people will dispose of them, and they will talk about it in social media channels. With all the effort you put into the development of this business product, you have one chance to impress.

This applies to language as well. You have to pay attention to who you are speaking to and put yourself in their shoes to begin understanding what their thought process is. In the 1960’s when denim was primarily used for work pants, rock stars like Keith Richards from the Rolling Stones wore jeans as the uniform of the rebel. Zooming forward to current day, jeans have become the uniform of the masses across all age groups and are worn casually and also for work – from the farm to the corporate office. Willie Nelson and a female model, both in their 70s and with grey hair, appeared in ads for Gap jeans, showing us there has been a significant shift in demographics as well as in fashion trends. They represent the silver foxes and silver dollar who might have once been rebels whose perspectives have been shaped by time and experience in ways that are likely different than their parents. We have to be mindful that what was speaking to one person or generation may not speak to the next.

Empathy

Looking from the end point of the user helps us to develop empathy, which is a critical factor in building relationships and being able to communicate effectively with others. Not everyone is capable or willing to develop empathy for others. For some it can be learned, but for some they literally lack the ability to empathise with anyone beyond themselves.16

e. Recognise that shared commitment only comes after shared understanding.

Barriers to communication

All the elements that contribute to a person’s empathic horizon can either enable their ability to empathise with others or provide potential barriers to their communicating with others. Note that two individuals with almost identical lives will not necessarily respond in the same way to a particular context. This also applies to how they communicate to others.

Overcoming barriers to build relationships

Barclays Bank in the UK has used the local term for cash dispensers ‘hole in the wall’ (also known as Automated Teller Machines (ATM)) in a way that projects an image of a bank that uses the language of its customers (Figure 8). Using the local vernacular and terminology can provide a connection between a business and its customer. Though this may only being a marketing tool (trick), it is effective one.

Figure 8. Use of the local vernacular.

Designers’ ways of communicating

Designers, who use their creativity to imagine how a product, service or environment could be in the near future, rely heavily on visual forms of communication (such as mood boards, two-dimensional drawings, three-dimensional sketches and models). The ability to elicit user needs and communicate concepts developed is a common challenge shared with entrepreneurs and business people.

The following forms of communication are presented as alternative ways to begin dialogue in business while not relying on words alone. By introducing different levels of engagement and interaction, the following tools can help pave the way for a more meaningful interaction as a foundation for developing a shared language.

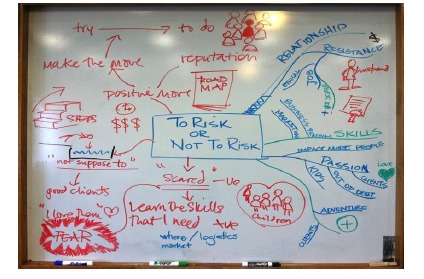

Mind mapping (Figure 9a) is a tool that supports brainstorming where key words, phrases, thoughts or actions are written on Post-it notes and arranged on a surface. This activity can be performed individually, or in small teams. They can be arranged and framed multiple times until clusters or patterns of information emerge that can help guide and direct the team.

Figure 9 a, b. Mind mapping with notes, keywords and sketches.

Figure 9b shows another variation of mind mapping where the main idea is placed at the center of the page (or in this case a white board) and fluid lines branch out from it, connecting phrases and rapid sketches. This tool can help identify and connect previously unconnected elements which may not have been possible through more linear forms of data presentation such as list making. Designers tend to employ this tool early in their designing process to ensure they explore the diverse contributory factors to their particular users’ needs, users’ context and use environment. This process tends to bring to the surface issues, concerns and topics that may not have otherwise been raised.

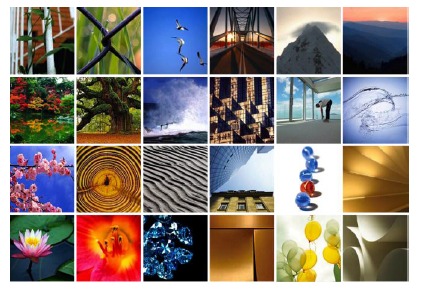

Mood boards (Figure 10) provide an approach that brings together a visual and emotional response to the identified problem that a design solution will rectify. By compiling an emotional mood board (comprised of non-literal, abstract images and avoiding religious symbols) the designer can communicate and evoke the suprafunctional needs that their design (the product) should to satisfy beyond the functional.6 In addition to assisting in the creative process, this tool also provides key visual cues that will support the designer later in the designing process when dampening of creativity can occur due to manufacturing constraints, cost and user product feedback. Mood boards can be compared to ‘vision boards’ that individuals create to represent their personal aspirations and therefore provide another form of communication. Caution is necessary when you are sharing these abstract images with others as so much of our interpretation of the visual is influenced by our empathic horizon .

Figure 10. Mood board for the ‘New Old’.

3. What is the outcome of developing shared language and how does this manifest itself?

Consider your sphere of influence

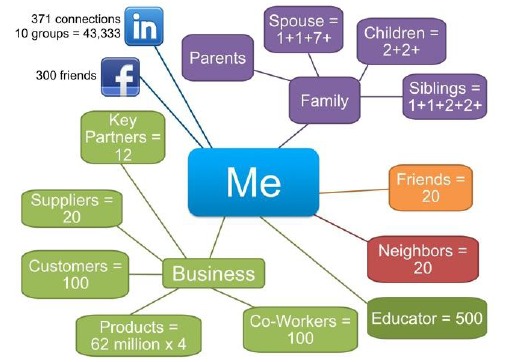

Who and how many people do you connect with? The sphere of influence that each of us has is the reason for thinking about shared language.

One of the authors (a product designer and educator) evaluated her sphere of influence. She started counting her connections with people, looking at family, friends, business and academic colleagues, students, as well as her connections through social media. These human connections total nearly 45,000. When you add in the people touched by the products she designed (64 million units sold x 4 as more than one person would use each of these products), that 'shared language' sphere of influence is an amazing number – 248,000,000+ people.Figure 11

Figure 11. One author’s sphere of influence.

Your sphere of influence may be more or less than this author’s; however, the point is to be aware that your words and actions can have a significant impact well beyond your intimate circle.

If you step back one 'generation' and look at one of your teachers or professors and refer only to the number of students that your educator taught (not counting all of the rest of their sphere) and assume each of their students would have a sphere of influence similar to your own, you would extrapolate out a huge sphere of influence for that person. Likewise, looking forward from yourself you should recognize that the people who are in your direct sphere of influence will carry forward what and how you are communicating.

The total of these numbers can be a powerful reminder that your words and actions, your 'Shared Language' makes a difference in the world.

Findings

The language we use may not be helping us to communicate effectively. Being mindful and sensitive to your own use of spoken language, body language, facial expressions and behavior will help to reduce potential barriers to communication (for instance, some people think in text while others are more visual). Patience, mutual respect, time, intent and willingness from all parties are required to develop a shared language. Recognize that shared commitment only comes after shared understanding. Through the process of developing a shared language between individuals, their working (and personal) relationship is often enhanced.

Mood boards and mind mapping are typical tools for designers to use, but the authors advocate that these tools also support non-design based individuals to communicate in alternative ways. We are living and working in an increasingly smaller global community. It is the responsibility of the individual to communicate effectively and contribute to the process so that business, education, social and professional interactions are as productive as possible.

Conclusions and implications

As communication is key to human interaction, it is equally vital to business. Assume everyone has different stuff. Shared language is the stuff of collaboration – across disciplines, families, cultures – it is our ability to communicate in words, images, products and more. Developing and nurturing a shared language between all members is an essential element to enhance communication and collaboration whether it is simply between partners or across the larger community of business and customers. Constant awareness and education is required to maintain the shared language.

You need to take stock of and ownership of your shared language. Look at the significance of your language and actions and recognise what you share has a large impact on our world. It is incredible how creative and innovative people are when they take the time to build their relationship by developing a shared language. Business is built on relationships. If you invest in shared language, it will help your business to thrive.

Language is shaping the world as we see it. Language is the lens through which we see the world, but also it is the lens through which the world sees you. We are creating the shared global language of tomorrow.

Footnotes

PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned. Externally peer reviewed.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Please cite this paper as: Thomas J, McDonagh D. Shared language: Towards more effective communication. AMJ 2013, 6, 1, 46-54.http//dx.doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2013.1596.

References

- 1.Milroy L. Britain and the United States: Two nations divided by the same language (and different language ideologies) Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 2000;10:56–89. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keyes R. Euphemania: Show me the liquidity. The Antioch Review. 2011;69:58–72. Available from: http://www.ralphkeyes.com/wpcontent/uploads/2011/10/AR-Euphemania.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackburn B, Williamson R. Pressing forward with professional development. Principal Leadership. 2010:68–70. Available at: http://barbarablackburnonline.com/app/download/6480569804/Staff+Development+(Principal+Leadership).pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnan LR, Rajamanickam V. At the Global Conference on Excellence in Education and Training, Singapore Polytechnic. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong A. The latent semantic approach to studying design team communication. Design Studies. 2005;26:445–61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonagh D, Thomas J, Khuri L, Heft Sears S, Peña-Mora F. In: Handbook of research on trends in product design and development: Technological and organisational perspectives. Silva A, Simoes R, editors. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; 2010. Empathic design research strategy: People with disabilities designing for all. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinek S. Portfolio Trade. New York: 2009a. Start with Why: How great leaders inspire everyone to take action. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinek S. Inspire people: Simply start with why. Leadership Excellence. 26(13) 2/3p. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brothers C. New Possibilities Press; Naples, FL.: 2005. Language and the pursuit of happiness: A new foundation for designing your life, your relationships and your results. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spuzic S, Abhary K, Stevens C, Fabris N, Rice J, Nouwens F. Contribution to cross-disciplinary lexicon. In: Proceedings of the 2005 ASEE/AaeE 4th Global Colloquium on Engineering Education, Australasian Association for Engineering Education. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns C, Cottam H, Vansonte C, Winhall J. RED PAPER 02 Transformation Design. Design Council, United Kingdom. 2006 Available at: http://www.designcouncil.info/mt/RED/transformationdesign/TransformationDesignFinalDraft.pdf.Excerpt from Charles Eames’ answers in Design Q&A, 1972 (5 minute color film by Charles and Ray Eames) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doblin J. A short, grandiose theory of design. STA Design Journal, Analysis and Intuition. 1987:6–15. Available at: http://www.chicagodesignarchive.org/pdfs/sta_design_journal_jaydoblin.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehrer J. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2012. Imagine: How creativity works. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonagh D, Thomas J, Strickfaden M. Empathic design research: Towards a new mode of industrial design education. Design Principles & Practices: An International Journal. 2011;5:301–14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruiz DM. Sinek S. Sinek S. Leadership Excellence. Vol. 26. San Rafael, CA: Amber-Allen Publishing; New York: Portfolio Trade; 1997. 2009a. 2009b. 2009. The Four Agreements. Start with Why: How great leaders inspire everyone to take action. Inspire people: Simply start with why. p. 13. 2/3p. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sterzer P, Stadler C, Poustka F, Kleinschmidt A. A structural neural deficit in adolescents with conduct disorder and its association with lack of empathy. NeurioImage. 2007;37:335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]