Abstract

This study examined the prospective relationships among borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptoms, interpersonal problems, and types of aggressive behaviors (i.e., experiencing psychological and physical victimization and perpetrating psychological and physical aggression) in a psychiatric sample (N = 139) over the course of 2 years. We controlled for other PD symptoms and demographic variables. BPD symptoms at baseline were associated with interpersonal sensitivity, interpersonal ambivalence, interpersonal aggression, need for social approval, and lack of sociability 6 months later. In turn, interpersonal sensitivity predicted not experiencing physical aggression, interpersonal aggression predicted experiencing physical aggression and perpetrating both psychological and physical aggression, need for social approval predicted experiencing both psychological and physical aggression, and lack of sociability predicted perpetrating physical aggression 2 years later. Results demonstrated that interpersonal problems mediated the relationship between BPD and later violent behaviors. Our findings suggest the importance of distinguishing between these groups of aggressive behaviors in terms of etiological pathways, maintenance processes, and treatment interventions.

Keywords: borderline personality disorder, aggression, interpersonal problems

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by a pattern of intense and stormy relationships, uncontrollable anger, affective instability, and poor impulse control (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Research has demonstrated that BPD is a risk factor for victimization as well as perpetrating aggressive behaviors (e.g., Ross & Babcock, 2009; Sansone, Reddington, Sky, & Wiederman, 2007). In addition, a core feature of BPD is chronic and severe interpersonal dysfunction, which is defined by intense and stormy relationships, fears of abandonment, and vacillations between idealization and devaluation within relationships (Clarkin, Widiger, Frances, Hurt, & Gilmore, 1983; Gunderson, 2007; Kehrer & Linehan, 1996). Interpersonal problems also put individuals at risk for experiencing as well as perpetrating aggressive behaviors (Ayduk et al., 2000; Murphy & Blumenthal, 2000). However, no study has yet examined whether specific types of interpersonal problems explain the association between BPD and different types of aggressive behaviors. If the link between BPD and aggression is mediated by particular interpersonal problems, it would have implications for treatment targets in populations with BPD to reduce the likelihood of victimization as well as the perpetration of physical and psychological forms of aggression.

BPD and Aggressive Behaviors

BPD is marked by high levels of aggression on self-report (Burnette & Reppucci, 2009; Fossati et al., 2005; Ostrov & Houston, 2008; Rogosch & Cicchetti, 2005) and laboratory measures (Dougherty, Bjork, Huckabee, Moeller, & Swann, 1999; McCloskey et al., 2009). McCloskey and colleagues (2009) found that laboratory indexes of aggression differentiated BPD from other Axis I conditions but not from other Axis II disorders, such as antisocial PD (ASPD), demonstrating some specificity for aggression in BPD.

Many studies have demonstrated an association between BPD symptoms and intimate partner aggression, including the perpetration of physical, emotional, and sexual aggression (Dutton, 1995; Edwards, Scott, Yarvis, Paizis, & Panizzon, 2003; Hines, 2008; Holtzworth-Munroe, Bates, Smutzler, & Sandin, 1997; Hughes, Stuart, Gordon, & Moore, 2007; Porcerelli, Cogan, & Hibbard, 2004; Mauricio, Tein, & Lopez, 2007; Ross & Babcock, 2009). Most of these studies recruited men or women who had been arrested for violence against an intimate partner, which limits the generalizability of the findings. For example, Hughes and colleagues (2007) found that in a sample of women arrested for intimate partner violence (n = 108), BPD symptoms were associated with increased levels of self-reported physically aggressive conflict tactics in romantic relationships. Hines (2008) found a relationship between BPD symptoms and physical, psychological, and sexual intimate partner aggression from general community samples of men and women across 67 sites around the world, indicating that the association between BPD and intimate partner aggression might be generalized to nonclinical populations.

BPD is also associated with perpetrating aggressive behaviors outside the context of romantic relationships. In a sample of men and women enrolled in a clinical trial for the treatment of PDs, those meeting criteria for both BPD and ASPD were more likely to have been convicted of a violent crime, had higher mean scores of trait anger, and outwardly expressed anger when compared with those with other PDs (Howard, Huband, Duggan, & Mannion, 2008). In addition, based on chart reviews of 81 adolescent inpatients, those with BPD were more likely to perpetrate aggression while on the unit (Faulkner, Grapentine, & Francis, 1999). Among female prison inmates, BPD was related to self-reported acts of aggression during institutionalization (Warren et al., 2002). Johnson and colleagues (2000) found that adolescents from a community sample with Cluster A and B PD symptoms were more likely to commit violent acts, including assault and threatening to cause bodily harm, compared with adolescents without these PD symptoms.

Finally, BPD is not only associated with the perpetration of aggressive behavior but also with victimization across the lifespan. For instance, individuals with BPD are likely to report exposure to childhood trauma, including sexual and physical abuse (Burnette & Reppucci, 2009; McClean & Gallop, 2003; Rogosch & Cicchetti, 2005; Wonderlich et al., 2001). Childhood abuse is related to revictimization in adulthood, including experiencing intimate partner aggression (Beitchman et al., 1992; Gladstone et al., 2004; Desai, Arias, Thompson, & Basile, 2002). Thus, individuals with BPD may be at increased risk for experiencing victimization in adulthood. The relationship between BPD and victimization in adult romantic relationships may be due, at least in part, to the fact that victimization and perpetration of aggression tend to be highly correlated (e.g., Marshall & Rose, 1990). Sansone and colleagues (2007) found that 64% of women in a primary care setting who reported experiencing intimate partner violence met criteria for BPD, whereas only 11% of nonabused women met diagnostic criteria, suggesting that BPD may increase the likelihood of victimization within romantic relationships.

Interpersonal Problems as Mediators Between BPD Symptoms and Aggressive Behaviors

No study has yet examined putative mechanisms that might explain the association between BPD and aggressive behaviors. It is important to identify factors that are more proximal to aggressive behaviors to predict those who are most likely to experience victimization and/or perpetrate aggressive behaviors as well as to develop interventions targeting the identified mechanisms. Interpersonal problems may explain the association between BPD and aggressive behaviors.

Interpersonal problems are also associated with aggressive behaviors. Patterns of verbal arguments and difficulty with conflict resolution are associated with perpetrating violence (Choice, Lamke, & Pittman, 1995; Foo & Margolin, 1995; Riggs & O’Leary, 1996). Murphy and Hoover (1999) found that domineering, intrusive, and vindictive styles of relating to others correlated with perpetrating psychological aggression in romantic relationships. Similarly, a controlling interpersonal style has been found to be associated with perpetrating violence in romantic relationships (Blumenthal, Neemann, & Murphy, 1998). Murphy and Blumenthal (2000) found that a domineering interpersonal style was related to perpetrating aggression as well as experiencing victimization in dating relationships. In addition, Ayduk and colleagues (2000) found that impulsive middle-school children who were high on rejection sensitivity were likely to be rated as aggressive by teachers and were more likely to be rejected by peers.

The interpersonal style of many individuals with BPD is characterized by hostile control and heightened sensitivity to rejection (Ayduk et al., 2008; Russell, Moskowitz, Zuroff, Sookman, & Paris, 2007; Stepp et al., 2009). Thus, the interpersonal problems associated with BPD might serve as more proximal variables that predict subsequent aggressive behaviors. This study extended previous findings regarding BPD, interpersonal problems, and aggression in several ways. First, we examined the differential prediction of psychological and physical victimization and perpetration of psychological and physical aggressive behaviors. These effects were examined after accounting for the contribution of other PD symptoms and known demographic risk factors of gender, age, and race, which bolsters the claim of specificity to BPD. Second, we collected information regarding aggressive behaviors that occur across all relationship contexts, not just romantic relationships. Finally, our study was longitudinal in nature, which allowed us to draw conclusions regarding the temporal ordering of these associations over the course of 2 years. The specific study hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 1: BPD will predict both victimization and perpetration of violence even after accounting for other PD symptoms.

Hypothesis 2: BPD will be uniquely associated with interpersonal problems characterized by sensitivity, ambivalence, and hostility.

Hypothesis 3: These interpersonal problems, in turn, will mediate the relationship between BPD and victimization and perpetration of violence.

Method

Sample

Patients (N = 138) from 21 to 60 years old were solicited from the general adult outpatient clinic at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic and were active in treatment at the time of participation in this study. Patients with psychotic disorder, organic mental disorders, and mental retardation were excluded, as were patients with major medical illnesses that influence the central nervous system and might be associated with organic personality change (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, cerebrovascular disease, seizure disorders). All study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

To examine the specificity of interpersonal dysfunction in BPD, we recruited patients from three groups: (a) those with BPD, (b) those with another PD (OthPD), and (c) those without a PD (NoPD). Announcements describing the study were posted in the clinic. Patients interested in participating contacted research staff and were prescreened by phone for the presence or absence of PD symptoms. An intake appointment was then scheduled. After completing intake procedures, 120 participants (87.0%) completed a 6-month follow-up appointment and 108 participants (78.3%) completed a 24-month follow-up session.

The mean age of the sample was 38 years (SD = 10.6) and 104 participants (75.4%) were female. One hundred three participants (74.6%) identified as White, 33 (23.9%) as African American, 1 (.7%) as Native American, and 1 (.7%) as Asian. Two participants (1.4%) identified ethnicity as Hispanic. In terms of marital status, 71 participants (51.4%) were single and never married, 36 (26.1%) were separated or divorced, 29 (21%) were married or in a long-term committed relationship, and 2 (1.4%) were widowed. A large majority of the sample obtained education beyond high school (n = 111; 80.4% with at least some vocational or college training), but the financial deprivation of the sample was high: 45.0% of the participants reported annual household incomes of less than US$10,000 and 66.7% less than US$20,000.

During the first assessment session, all patients were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-I; First et al., 1997b). The most prevalent current diagnoses were affective and anxiety disorders (n = 54; 39.1%), followed by more complex presentations (“other disorders”) that included eating, somatoform, dissociative, and sexual disorders comorbid with more common affective, anxiety, and substance use disorders (n = 29; 21.0%).

Measures

Consensus ratings of PD symptoms

Diagnostic assessments required three sessions, and each session lasted approximately 2 hr. Session 1 included administration of the SCID-I and other measures of current symptomatology. In session 2, a detailed social and developmental history was taken, using a semistructured interview, the Interpersonal Relations Assessment (IRA; Heape, Pilkonis, Lambert, & Proietti, 1989), developed for this purpose. During Session 3, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II; First et al., 1997a) was administered. Interviewers consisted of individuals with a minimum education level of a master’s degree in psychology or social work. Interviewers were trained to administer assessments by the principal investigator (PAP) and senior research staff.

After the evaluations, the primary interviewer presented the case to a research team (at least three individuals were present) at a 2- to 3-hour diagnostic conference. All available data (historical and concurrent) were reviewed and discussed at the conference. Judges were given access to all interview data that had been collected, including current and lifetime Axis I information, symptomatic status, social and developmental history, life events, and personality features. During the diagnostic conference, Axis I diagnoses were made and a checklist of Axis II criteria for all PDs was completed by consensus, with each item rated 0 (absent), 1 (present), or 2 (strongly present). Based on the best estimate diagnostic case conference, the total sample included 54 BPD participants, 55 participants with another personality disorder, and 29 participants with no significant personality dysfunction. The majority of the other personality disorder group was composed of patients with a DSM-IV Cluster C PD (n = 54; 98.2%). Participants in this group also met criteria for Cluster A (n = 5; 9.1%) and non-BPD Cluster B (n = 15; 27.3%) PDs. For the present analyses, we used the sum of BPD symptom severity and the sum of OthPD symptom severity as predictors in our models.

Interpersonal problems

At the 6-month follow-up session, participants completed an adapted version of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz, Rosenberg, Baer, Ureno, & Villasenor, 1988). We selected 24 items to allow scoring of the IIP-Personality Disorder scales (Pilkonis, Kim, Proietti, & Barkham, 1996). Items on the IIP are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely distressing. We calculated five scales—Interpersonal Sensitivity, Interpersonal Ambivalence, Aggression, Need for Social Approval, and Lack of Sociability—associated with PDs (Pilkonis et al., 1996).

The first three scales were empirically derived to discriminate between patients with any PD diagnosis versus no PD diagnosis. The fourth and fifth scales were empirically derived to discriminate between patients with a Cluster C PD and all others. The first scale, Interpersonal Sensitivity contains 11 items and includes items that suggest strong affectivity and reactivity: “I am too sensitive to rejection” and “It is hard for me to ignore criticism from other people.” The second scale, Interpersonal Ambivalence, contains 10 items that reflect content relating to struggling against others and an inability to join collaboratively in either work or love: “It is hard to accept another person’s authority over me,” “It is hard to be supportive of another person’s goals in life.” The third scale, Aggression, contained seven items tapping into hostile behavior that is primarily verbal in nature: “I argue with other people too much.” The fourth scale, Need for Social Approval, has nine items that suggest chronic anxiety about the evaluation of others: “I try to please other people too much.” The last scale, Lack of Sociability, contains 10 items that describe problems in socializing and distress in the presence of others: “It is hard to socialize with other people.” Alpha coefficients (assessing internal consistency reliability) for each scale were computed and ranged from .85 to .92 for interpersonal ambivalence and lack of sociability, respectively.

Aggressive behaviors

The frequency of victimization and perpetration of aggressive behaviors toward others during the past 2 years was assessed with the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) at the 24-month follow-up session. The CTS2 contains 78 items that assesses five subscales: Negotiation, Psychological Aggression, Physical Assault, Sexual Coercion, and Injury and is the most widely used scale for assessing violence in relationships (Straus et al., 1996). Items on the CTS2 are scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 = 0 times to 6 = 21 or more times.

For the current study, participants completed 40 items from the Psychological Aggression and Physical Assault subscales and items were slightly reworded to reflect victimization by anyone and perpetration against anyone, not just romantic partners. The CTS2 was scored by summing the ratings regarding the frequency of the behaviors in the past 2 years reported on each subscale differentiating between victim and perpetrator behaviors, which resulted in four constructs: Victim of Psychological Aggression (e.g., “How many times in the past 2 years did anyone insult or swear at you?”), Victim of Physical Aggression (e.g., “How many times in the past 2 years did anyone punch or hit you with something that could hurt?”), Perpetrator of Psychological Aggression (“How many times in the past 2 years did you threaten to hit or throw something at anyone?”), and Perpetrator of Physical Aggression (“How many times in the past 2 years did you beat anyone up?”). Alpha coefficients for each scale ranged from .78 to .89 for Perpetrator of Psychological Aggression and Victim of Physical Aggression, respectively. The scales were skewed, so we conducted square root transformations prior to conducting statistical analyses.

Data Analytic Strategy

We estimated multiple regressions simultaneously in a structural equation framework with Mplus software 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2008) to predict four types of aggressive behaviors: (a) experiencing psychological victimization, (b) experiencing physical victimization, (c) perpetrating psychological aggression, and (d) perpetrating physical aggression. To ensure that the effects of the predictors were independent of general personality pathology and demographic variables, we controlled for other PD symptoms, sex, age, and minority race.

Mediation occurs when the relationship between two variables can be explained (at least partially) by a path through a third, or intervening, variable. The relationships among the variables must be embedded within a theoretical rationale to ensure construct validity. Two ways to test the mediated effect are (a) to test the significance of the difference in the effect of the predictor on the outcome with and without the intervening variable (e.g., Baron & Kenny, 1986) and (b) to test the significance of the product of the coefficients from the predictor to the intervening variable and the intervening variable to the outcome (e.g., Sobel, 1982). Researchers have demonstrated that testing the product of the coefficients yields more statistical power than the Baron and Kenny causal steps method (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Thus, we used the regression coefficients predicting interpersonal processes from BPD and OthPD symptom severity scores and those predicting interpersonal processes to interpersonal violence to calculate the significance of the indirect effect.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Bivariate correlations among all study variables as well as means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. For ease of interpretation, we present the nontransformed means and standard deviations for the aggression variables in the table.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD symptoms, baseline | |||||||||||

| 1. BPD symptoms | — | ||||||||||

| 2. OthPD symptoms | .30**** | — | |||||||||

| Interpersonal problems, 6-month follow-up | |||||||||||

| 3. Sensitivity | .43**** | .25**** | — | ||||||||

| 4. Ambivalence | .23**** | .28**** | .50**** | — | |||||||

| 5. Aggression | .42**** | .08 | .59**** | .55**** | — | ||||||

| 6. Need for social approval | .27**** | .21**** | .81**** | .33**** | .28**** | — | |||||

| 7. Lack of sociability | .32**** | .33**** | .72**** | .44**** | .33**** | .74**** | — | ||||

| Aggressive behaviors, 24-month follow-up | |||||||||||

| 8. Victim, psychological aggression | .39**** | .14 | .40**** | .24**** | .28**** | .33**** | .17 | — | |||

| 9. Victim, physical aggression | .30**** | .10 | .25**** | .22**** | .33**** | .16 | .19 | .56**** | — | ||

| 10. Perpetrator, psychological aggression | .40**** | .14 | .32**** | .29**** | .47**** | .15 | .14 | .76**** | .43**** | — | |

| 11. Perpetrator physical aggression | .21**** | −.04 | .22**** | .22**** | .41**** | .11 | .19 | .42**** | .59**** | .61**** | — |

| M | 5.53 | 17.49 | 1.96 | 1.14 | 1.07 | 2.28 | 1.98 | 12.59 | 3.05 | 10.19 | 1.93 |

| SD | 4.89 | 9.09 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 8.23 | 6.12 | 7.21 | 5.05 |

Note: PD = personality disorder; BPD = borderline personality disorder; OthPD = other personality disorder. The means and standard deviations reported are for the variables prior to the square root transformation.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

To determine if multicollinearity was a significant problem in this study, we examined the variance inflation factors (VIFs), which is superior to examining bivariate correlations (Mansfield & Helms, 1982). For VIFs, we used the conventional cutoff value ≥ 10 to indicate cause for concern (e.g., Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1995). We ran several multiple regressions, regressing each predictor on all other predictors. The highest VIF value was 2.64, indicating that multicollinearity was not a significant problem in this study.

Interpersonal Problems as Mediators Between BPD Symptoms and Aggressive Behaviors

Interpersonal problems were tested as potential mediators of the effects of BPD symptoms on experiencing and perpetrating both psychological and physical aggressive behaviors. We estimated a multiple regression model simultaneously predicting types of aggressive behaviors from sex, age, minority race, OthPD symptoms, BPD symptoms, and interpersonal problems. The first part of the model tested BPD and OthPD symptoms at baseline predicting interpersonal problems 6 months later. Consistent with research demonstrating the deleterious effects of PD symptoms on interpersonal experiences, BPD symptoms at baseline significantly predicted higher levels of interpersonal sensitivity, interpersonal aggression, need for social approval, and lack of sociability (after adjusting for OthPD symptoms, sex, age, and ethnicity) 6 months later. In addition, BPD symptoms marginally predicted higher levels of interpersonal ambivalence. OthPD symptoms at baseline predicted greater interpersonal ambivalence and lack of sociability. OthPD symptoms also marginally predicted need for social approval. Results regarding the prediction of interpersonal problems are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression Predicting Interpersonal Problems at 6 Months From Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms at Baseline

| Sensitivity |

Ambivalence |

Aggression |

Need for social approval |

Lack of sociability |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CIa | β | 95% CIa | β | 95% CIa | β | 95% CIa | β | 95% CIa | |

| Sex | .12 | [−.10, .34] | −.07 | [−.27, .14] | .02 | [−.15, .18] | .08 | [−.17, .33] | .06 | [−.17, .30] |

| Age | −.03 | [−.20, .14] | .01 | [−.16, .18] | −.18** | [−.34, −.01] | −.09 | [−.26, .08] | −.01 | [−.20, .17] |

| Minority race | −.22** | [−.40, −.04] | .04 | [−.16, .25] | .06 | [−.10, .22] | −.28*** | [−.46, −.10] | −.15 | [−.34, .05] |

| Other personality disorder symptoms | .10 | [−.08, .28] | .23*** | [.06, .41] | −.01 | [−.22, .13] | .18* | [−.01, .37] | .22** | [.03, .42] |

| Borderline personality disorder symptoms | .38**** | [.20, .55] | .15* | [–.01, .32] | .43**** | [.26, .60] | .19** | [.01, .37] | .25*** | [.08, .41] |

95% CI = 95% confidence intervals around the parameter estimates; Lower 2.5%, Upper 2.5%.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Results for the total model are presented in Table 3. Female sex was associated with experiencing victimization via physical aggression across 2 years. Younger age was also associated with experiencing and perpetrating aggressive behaviors. Minority race was positively associated with perpetrating physical aggression. We tested the prospective relationship of BPD and OthPD symptoms at intake and types of aggressive behaviors over 2 years. After adjusting for sex, age, and minority race, BPD symptoms predicted experiencing both psychological and physical victimization and perpetrating psychological aggression over 2 years. OthPD symptoms did not significantly predict experiencing or perpetrating any type of aggression over the 2-year period.

Table 3.

Multiple Regression Predicting Experiences of Interpersonal Aggression at 2 Years From Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms at Baseline and Interpersonal Problems at 6 Months

| Victim of psychological aggression |

Victim of physical aggression |

Perpetrator of psychological aggression |

Perpetrator of physical aggression |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CIa | β | 95% CIa | β | 95% CIa | β | 95% CIa | |

| Sex | −.05 | [–.20, .11] | −.17** | [–.31, –.03] | .12 | [–.04, .29] | .00 | [–.13, .13] |

| Age | −.17** | [–.32, –.02] | −.16*** | [–.28, –.05] | −.17** | [–.31, –.03] | −.21**** | [–.33, –.09] |

| Minority race | .09 | [.10, .28] | .11 | [–.04, .26] | .06 | [–.14, .25] | .21** | [.01, .43] |

| Other personality disorder symptoms | .01 | [–.15, .17] | .00 | [–.15, .15] | .03 | [–.15, .22] | −.13 | [–.32, .07] |

| Borderline personality disorder symptoms | .27**** | [.11, .44] | .18** | [.01, .35] | .28*** | [.10, .46] | .10 | [–.07, .27] |

| Sensitivity | −.04 | [–.35, .27] | −.49**** | [–.74, –.23] | .10 | [–.23, .42] | −.03 | [–.26, .19] |

| Ambivalence | .13 | [–.09, .34] | .10 | [–.14, .34] | .09 | [–.19, .36] | .04 | [–.25, .32] |

| Aggression | .06 | [–.17, .30] | .34** | [.07, .61] | .28* | [–.03, .58] | .34* | [–.02, .70] |

| Need for social approval | .44**** | [.25, .63] | .44**** | [.24, .63] | −.02 | [–.20, .16] | −.06 | [–.20, .08] |

| Lack of sociability | −.29** | [–.58, –.01] | −.08 | [–.30, .14] | −.09 | [–.43, .26] | .12* | [–.02, .26] |

95% CI = 95% confidence intervals around the odds ratios; Lower 2.5%, Upper 2.5%.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

In the same model (after adjusting for the effects of demographic variables and BPD and OthPD symptoms), interpersonal sensitivity predicted experiencing physical aggression victimization. Interpersonal aggression predicted experiencing physical aggression victimization as well as perpetrating both psychological and physical aggression. Need for social approval predicted being a victim of both physical and psychological aggression. Lack of sociability negatively predicted being a victim of psychological aggression and positively predicted perpetrating physical aggression. Interpersonal ambivalence did not predict any type of aggressive behavior.

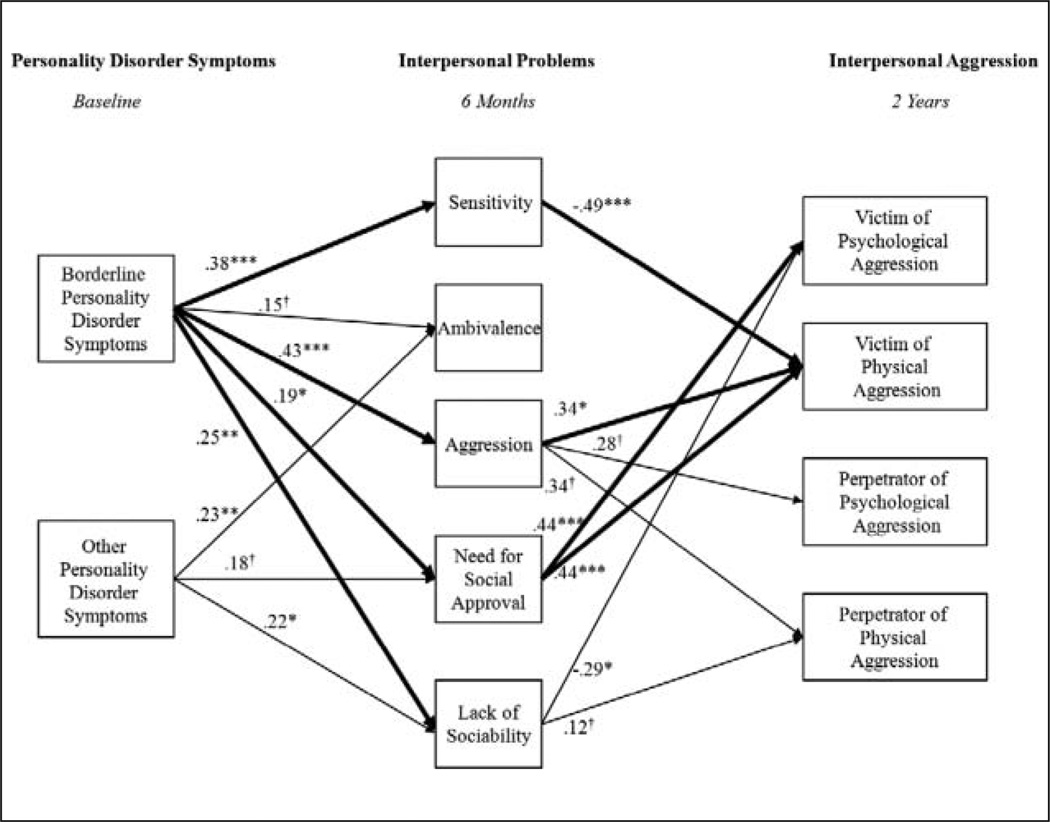

We then used the coefficients from the multiple regression to test the significance of the indirect (mediated) paths (i.e., PD symptoms → Interpersonal problems → Aggressive behaviors), for each type of aggressive behavior. To test the significance of the indirect effects, we conducted Sobel’s test for mediation (Sobel, 1982). This method of testing the product of coefficients increases the statistical power to detect effects above the Baron and Kenny (1986) causal step method (MacKinnon et al., 2002). We also calculated the proportion of the total effect of BPD and OthPD symptoms on the outcome that was indirect through interpersonal processes (MacKinnon, Warsi, & Dwyer, 1995). Results are depicted in Figure 1, in which bold lines represent significant indirect effects.

Figure 1. Interpersonal problems as mediators in the relationship between borderline personality disorder symptoms and interpersonal aggression.

The numbers presented are the standardized regression coefficients obtained from the multiple regression predicting categories of interpersonal aggression from personality disorder symptoms and interpersonal problems (sex, minority race, and age were controlled). Only the significant indirect pathways are shown. The thick lines represent significant mediational pathways.

*p < .10. **p < .05. ***p < .01. ****p <.001.

There was a significant indirect effect of BPD symptoms through need for approval predicting being a victim of psychological aggression (z = 2.09, 25.94% mediated and z = 1.68, 16.73% mediated, respectively). There was also a significant indirect effect of BPD symptoms through interpersonal sensitivity (z = −2.27, 51.08% mediated), interpersonal aggression (z = 1.98, 43.97% mediated), and need for approval (z = 1.87, 33.93% mediated) predicting victimization via physical aggression. The indirect effect of BPD symptoms through interpersonal aggression was also a significant predictor of perpetrating both psychological (z = 1.77, 30.96% mediated) and physical (z = 1.80, 57.62% mediated) aggression. Last, the indirect effect of BPD symptoms through lack of sociability was marginally predictive of perpetrating physical aggression (z = 1.68, 22.83% mediated). There was only one significant indirect effect of OthPD symptoms through interpersonal sensitivity marginally predicting victimization via psychological aggression (z = 1.68, 16.73% mediated).

Discussion

The present study examined interpersonal problems as a mediator of the effects of BPD symptoms on types of aggressive behaviors across a 2-year period in a psychiatric sample. We extend previous work in this area by controlling for other PD symptoms and demographic variables as well as testing these associations in a longitudinal framework. We examined whether specific interpersonal difficulties differentially mediated the relationships between BPD and four types of aggressive behaviors: (a) experiencing psychological victimization, (b) experiencing physical victimization, (c) perpetrating psychological aggression, and (d) perpetrating physical aggression.

The first finding of interest was that BPD symptoms uniquely predicted interpersonal problems 6 months later after controlling for other PD symptoms and demographic characteristics. Specifically, BPD symptoms predicted interpersonal sensitivity, interpersonal aggression, need for social approval, and lack of sociability. BPD symptoms only marginally predicted interpersonal ambivalence. Second, BPD symptoms predicted aggressive behaviors over the subsequent 2-year period, which is consistent with findings from previous cross-sectional studies (e.g., Dutton, 1995; Ross & Babcock, 2009). BPD symptoms uniquely predicted experiencing both psychological and physical victimization as well as perpetrating psychological aggression toward others. Although we found a significant bivariate association between BPD symptoms and perpetration of physical aggression, these symptoms did not uniquely predict perpetrating physical aggression after controlling for demographic variables, interpersonal problems, and other PD symptoms. Age was also predictive of aggressive behaviors; younger age was associated with more violence over the subsequent 2-year period. This result underscores the importance of controlling for other PD symptoms and demographic variables to understand the specificity of the relationship between BPD, interpersonal problems, and aggressive behaviors.

Interpersonal problems mediated the relationship between BPD symptoms and subsequent aggressive behaviors. Specifically, BPD symptoms predicted interpersonal sensitivity, interpersonal aggression, need for social approval, and lack of sociability, which in turn predicted aggressive behavior over the 2-year period. Interestingly, higher levels of interpersonal sensitivity were associated with less risk for aggressive behavior. This could be because individuals with high levels of interpersonal sensitivity are concerned about the fallout that ensues from violence, which serves to inhibit impulsive aggression. Thus, the effects of BPD symptoms on aggressive behaviors can be accounted for, at least in part, by more specific interpersonal problems. Findings point to specific interpersonal mechanisms that may place individuals with BPD at risk for experiencing violence as well as perpetrating aggressive behaviors, highlighting the need for assessment of interpersonal difficulties in patients with BPD.

An important contribution of the present study is the distinction among different types of aggressive behaviors, including experiencing and perpetrating both psychological and physical aggression, in examining mediational pathways. Interpersonal sensitivity predicted less victimization via physical aggression over the subsequent 2-year period. This finding suggests that high levels of interpersonal sensitivity in individuals with BPD may protect them from being physically victimized. It is possible that individuals with BPD who are highly sensitive to criticism may avoid relationships with individuals who are prone to engage in violent behavior. In contrast, IIP-reported aggression (i.e., verbal aggression and hostility) predicted more victimization via physical aggression over the subsequent 2-year period. In addition, those with high levels of IIP-reported aggression were somewhat more likely to perpetrate both psychological and physical aggression over the 2-year period. These findings regarding the importance of verbal aggression and hostility in predicting subsequent victimization and perpetration are consistent with previous results reporting a link between verbal aggression and violence in romantic relationships (e.g., Choice et al., 1995; Kalmuss, 1984). Our results suggest that verbal aggression and hostility are possible mechanisms that explain the high correlation between perpetration and victimization (e.g., Marshall & Rose, 1990). Interestingly, need for social approval predicted experiencing more victimization via psychological and physical aggression, suggesting that individuals who are overly concerned with pleasing others are at high risk for experiencing victimization. This could possibly be because these individuals find it particularly difficult to leave abusive relationships. Last, lack of sociability was somewhat predictive of perpetrating physical aggression toward others over the subsequent 2-year period, which is also consistent with previous work identifying associations between difficulties with conflict resolution and violent behavior in romantic relationships (Foo & Margolin, 1995; Riggs & O’Leary, 1996). Findings suggest that individuals who perpetrate aggressive behaviors may not have the social skills to successfully negotiate with others during a disagreement.

Strengths of the study include the multimethod, intensive, and longitudinal assessment process, the distinction between categories of aggressive behavior, and the provision of a theoretically coherent interpersonal context for aggression. By demonstrating that separate interpersonal mechanisms underlie these different types of behaviors, this study highlights the importance of distinguishing between them. We used clinician assessment of PD symptoms and then relied on a consensus model of rating the presence of each symptom. The interpersonal problems were assessed via self-report at 6-month follow-up and the aggressive behaviors were also assessed via self-report 2 years after the baseline assessment. Elucidating an interpersonal framework for different types of aggressive behavior is an important contribution for understanding interpersonal violence and extends our previous work regarding these interpersonal problems as mediators of suicide and self-harm behaviors (Stepp et al., 2008).

The results of this research are not without limitations. We were not able to control for previous aggressive behaviors, so we are not able to conclude that BPD symptoms and interpersonal problems predicted a change in aggressive behaviors. However, we did ask only about aggressive behaviors that occurred in the 2-year period following the baseline assessment. Importantly, the causal assumptions underlying these analyses cannot be confirmed directly, but it is plausible that a transactional relationship occurs between aggressive behaviors and interpersonal problems. For example, individuals who are overly concerned with pleasing others are more likely to experience victimization, which in turn also increases their need for social approval, making future victimization more likely. Future work should examine a state-trait model of interpersonal problems and aggressive behavior prospectively to better understand the dynamic nature of these constructs. The relatively small size of our sample precluded our ability to test these models. The sample was predominately female which is consistent with the preponderance of women with BPD in clinical samples (Skodol & Bender, 2003). However, these findings may not generalize to community samples with BPD or to men.

In sum, individuals in a psychiatric setting with BPD are likely to experience interpersonal problems, which, in turn, may lead to victimization and perpetration of aggression toward others. For example, lack of sociability may lead to the perpetration of violence. This highlights the clinical utility of screening for interpersonal problems in this population as a way to identify those who appear to be at risk for violent behaviors. In addition, findings suggest the importance of interpersonal skills training for individuals with BPD who experience and engage in aggressive behaviors (Linehan, 1993; McLeavey, Daley, Ludgate, & Murray, 1994).

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH56888; principal investigator: Paul A. Pilkonis). Michael N. Hallquist received postdoctoral support from T32 MH018269 (principal investigator: Paul A. Pilkonis). Stephanie Stepp’s effort was supported by K01 MH086713.

Biographies

Stephanie D. Stepp is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Psychology at the University of Pittsburgh. She is an expert on borderline personality disorder and the emotional and interpersonal factors that affect the development and maintenance of this disorder. She also has an interest in the assessment of personality disorders. She has expertise in using sophisticated statistical methods to model longitudinal data and to improve assessment instruments, including growth mixture and item response theory (IRT) models. She recently received a Career Development Award to investigate the development of borderline personality disorder in adolescent girls (K01 MH086713).

Tiffany D. Smith is a research assistant on the Girls Personality Project (principal investigator: Stephanie D. Stepp, K01 MH086713), which is designed to examine the development of adolescent girls who are at risk for developing borderline personality disorder. She runs the day-to-day operations of this study. She is primarily interested in the intersection of developmental psychopathology and personality.

Jennifer Q. Morse is an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Her research interests are in normal and maladaptive personality styles, their development across the life span, particularly in adulthood. She is currently completing a research project assessing adaptive coping strategies across the lifespan and how they relate to both physical and mental health. This project has used qualitative methods to write potential scale item and will use IRT to examine the psychometric properties of those items.

Michael N. Hallquist is a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Pittsburgh. He has expertise in using sophisticated longitudinal data analytic techniques to identify latent classes of individuals with borderline personality disorder as well as other type of personality pathology.

Paul A. Pilkonis is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. His primary scientific commitment is clinical research, both (a) research on psychopathology, with a focus on measurement and modeling of affective symptoms and personality, including extensive experience with psychometric models in PROMIS I, and (b) research on psychosocial treatments for affective and personality disorders (principal investigator, Personality Studies Program funded by NIH since 1990, MH56888). He has had the privilege of participating in the NIH research enterprise from several perspectives—as an investigator, member and chair of review committees, and scientific advisor at NIMH, giving him firsthand knowledge of federal research administration. He was associate director of research administration and development at WPIC from 1997 to 2004.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Revised Text Edition. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ayduk Ö, Mendoza-Denton R, Mischel W, Downey G, Peake PK, Rodriquez M. Regulating the interpersonal self: Strategic self-regulation for coping with rejection sensitivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:776–792. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayduk Ö, Zayas V, Downey G, Cole AB, Shoda Y, Mischel W. Rejection sensitivity and executive control: Joint predictors of borderline personality features. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008;42:151–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, daCosta GA, Akman D, Cassavia E. A review of the long-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1992;16:101–118. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90011-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal DR, Neemann J, Murphy CM. Lifetime exposure to interparental physical and verbal aggression and symptom expression in college students. Violence and Victims. 1998;13(2):175–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette ML, Reppucci ND. Childhood abuse and aggression in girls: The contribution of borderline personality disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:309–317. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choice P, Lamke LK, Pittmann JF. Conflict resolution strategies and marital distress as mediating factors in the link between witnessing interparental violence and wife battering. Violence and Victims. 1995;10:107–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin JF, Widiger T, Frances A, Hurt SW, Gilmore M. Prototypic typology and the borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1983;92:263–275. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.92.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Arias I, Thompson MP, Basile KC. Childhood victimization and subsequent adult revictimization assessed in a nationally representative sample of men and women. Violence and Victims. 2002;17(6):639–653. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.6.639.33725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Bjork JM, Huckabee HCG, Moeller FG, Swann AC. Laboratory measures of aggression and impulsivity in women with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research. 1999;85:315–326. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG. A scale to measure propensity for abusiveness. Journal of Family Violence. 1995;10(2):203–221. doi: 10.1007/BF02110600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DW, Scott CL, Yarvis RM, Paizis CL, Panizzon MS. Impulsiveness, impulsive aggression, personality disorder, and spousal violence. Violence and Victims. 2003;18:3–14. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner CJ, Grapentine WL, Francis G. A behavioral comparison of female adolescent inpatients with and without borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1999;40:429–433. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997a. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders –clinician version. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997b. [Google Scholar]

- Foo L, Margolin G. A multivariate investigation of dating aggression. Journal of Family Violence. 1995;10:351–377. [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A, Feeney JA, Carretta I, Grazioli F, Milesi R, Leonardi B, Maffei C. Modeling the relationships between adult attachment patterns and borderline personality disorder: The role of impulsivity and aggressiveness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24:520–537. [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone GL, Parker GB, Mitchell PB, Malhi GS, Wilhelm K, Austin MP. Implications of childhood trauma for depressed women: an analysis of pathways from childhood sexual abuse to deliberate self-harm and revictimization. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1417–1425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG. Disturbed relationships as a phenotype for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1637–1640. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Multivariate data analysis. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Heape CL, Pilkonis PA, Lambert J, Proietti JM. Interpersonal relations assessment. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh, Department of Psychiatry; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA. Borderline personality traits and intimate partner aggression: An international multisite, cross-gender analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:290–302. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Bates A, Smutzler N, Sandin E. A brief review of the research on husband violence. Part I: Maritally violent versus nonviolent men. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1997;2:65–99. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, Baer BA, Ureno G, Villasenor VS. Inventory of interpersonal problems: Psychometric properties and clinical applications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:885–892. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard RC, Huband N, Duggan C, Mannion A. Exploring the link between personality disorder and criminality in a community sample. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22:589–603. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.6.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes FM, Stuart GL, Gordon KC, Moore TM. Predicting the use of aggressive conflict tactics in a sample of women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Smailes E, Kasen S, Oldham JM, Skodol AE. Adolescent personality disorders associated with violence and criminal behavior during adolescence and early adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1406–1412. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmuss DS. The intergenerational transmission of marital aggression. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1984;46(1):11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer CA, Linehan MM. Interpersonal and emotional problem-solving skills and parasuicide among women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1996;10:153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guildford; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995;30:41–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield ER, Helms BP. Detecting multicollinearity. The American Statistician. 1982;36:158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall LL, Rose P. Premarital violence: The impact of family of origin violence, stress, and reciprocity. Violence and Victims. 1990;5:51–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauricio AM, Tein JY, Lopez FG. Borderline and antisocial personality scores as mediators between attachment and intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims. 2007;22:139–157. doi: 10.1891/088667007780477339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey MS, New AS, Siever LJ, Goodman M, Koenigsberg HW, Flory JD, Coccaro EF. Evaluation of behavioral impulsivity and aggression tasks as endophenotypes for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:1036–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean LM, Gallop R. Implications of childhood sexual abuse for adult borderline personality disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:369–371. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeavey BC, Daly RJ, Ludgate JW, Murray CM. Interpersonal problem solving skills training in the treatment of self-poisoning patients. Suicide & Life Threatening Behavior. 1994;24:382–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Blumenthal DR. The mediating influence of interpersonal problems on the intergenerational transmission of relationship aggression. Personal Relationships. 2000;7:203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Hoover SA. Measuring emotional abuse in dating relationships as a multifactorial construct. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:39–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus (Version 5.2) [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrov JM, Houston RJ. The utility of forms and functions of aggression in emerging adulthood: Association with personality disorder symptomatology. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:1147–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Kim Y, Proietti JM, Barkham M. Scales for personality disorders developed from the inventory of interpersonal problems. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1996;10:355–369. [Google Scholar]

- Porcerelli JH, Cogan R, Hibbard S. Personality characteristics of partner violent men: A Q-sort approach. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:151–162. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.2.151.32776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs D, O’Leary K. Aggression between heterosexual dating partners. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996;11:519–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Child maltreatment, attention networks, and potential precursors to borderline personality disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:1071–1089. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JJ, Moskowitz DS, Zuroff DC, Sookman D, Paris J. Stability and variability of affective experience and interpersonal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:578–588. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JM, Babcock JC. Proactive and reactive violence among intimate partner violent men diagnosed with antisocial and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Family Violence. 2009;24:607–617. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Reddington A, Sky K, Wiederman MW. Borderline personality symptomatology and history of domestic violence among women in an internal medicine setting. Violence and Victims. 2007;22:120–126. doi: 10.1891/vv-v22i1a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Bender DS. Why are women diagnosed borderline more than men? Psychiatric Quarterly. 2003;74:349–360. doi: 10.1023/a:1026087410516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology 1982. Washington, DC: American Sociological Society; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stepp SD, Morse JQ, Yaggi KE, Reynolds SK, Reed LI, Pilkonis PA. The role of attachment styles and interpersonal problems in suicide-related behaviors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38:592–607. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.5.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp SD, Pilkonis PA, Yaggi KE, Morse JQ, Feske U. Interpersonal and emotional experiences of social interactions in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2009;197:484–491. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181aad2e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Warren JI, Burnette ML, South SC, Chauhan P, Bale R, Friend R. Personality disorders and violence among female prison inmates. Journal of the Academy of Psychiatry and Law. 2002;30:502–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Crosby RA, Mitchell JE, Thompson K, Smyth JM, Redlin J, Jones-Paxton M. Sexual trauma and personality: Developmental vulnerability and additive effects. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2001;15:496–504. doi: 10.1521/pedi.15.6.496.19193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]