Abstract

Background

In atherosclerosis, local generation of reactive oxygen species amplifies the inflammatory response and contributes to plaque vulnerability. We used molecular imaging to test whether inhibition of NADPH oxidase with apocynin would reduce endothelial inflammatory activation and endothelial-platelet interactions, thereby interrupting progression to high-risk plaque phenotype.

Methods and Results

Mice deficient for both the LDL receptor and Apobec-1 were studied at 30 weeks of age and again after 10 weeks with or without apocynin treatment (10 or 50 mg/kg/day orally). In vivo molecular imaging of VCAM-1, P-selectin and platelet GPIbα in the thoracic aorta was performed with targeted contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEU) molecular imaging. Arterial elastic modulus and pulse wave transit time were assessed using ultra-high frequency ultrasound and invasive hemodynamic measurements. Plaque size and composition were assessed by histology. Molecular imaging in non-treated mice detected a 2-fold increase in P-selectin expression, VCAM-1 expression, and platelet adhesion between 30 and 40 wks of age. Apocynin reduced all of these endothelial events in a dose-dependent fashion (25% and 50% reduction in signal at 40 weeks for low- and high-dose apocynin). Apocynin also decreased aortic elastic modulus and increased the pulse transit time. On histology, apocynin reduced total monocyte accumulation in a dose-dependent manner as well as platelet adhesion, although total plaque area was reduced in only the high-dose apocynin treatment group.

Conclusions

Inhibition of NADPH oxidase in advanced atherosclerosis reduces endothelial activation and platelet adhesion; which are likely responsible for the arrest of plaque growth and improvement of vascular mechanical properties.

Keywords: contrast ultrasound, microbubbles, oxidative stress, platelets

Oxidative stress plays a key role in both the progression of atherosclerotic disease and susceptibility to acute atherothrombotic complications.1,2 Local production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is thought to contribute to pathophysiology in part through upregulation of endothelial adhesion molecules that mediate the inflammatory response and the promotion of platelet adhesion,2–5 although methods for quantifying these important responses in vivo have not been readily available. Membrane-bound NADPH oxidase is a major source for superoxide production not only by leukocytes, but also by vascular cells such as endothelial and smooth muscle cells.4,6,7 Its causal role in atherosclerosis is supported by data showing that gene-targeted deletion of cytosolic components of NADPH oxidase reduces plaque size in atherosclerotic mouse models.8 Although statins and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors may provide protection partly through their inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity, there are no clinically approved therapies that are specifically targeted against this enzyme complex.

Apocynin is a plant-derived inhibitor of NADPH oxidase that has been used to treat inflammatory diseases such as asthma and arthritis.7 It is thought to reduce oxidative stress by preventing the translocation of cytosolic oxidase subunits of NADPH oxidase such as p47phox.7,9 Apocynin has been shown to reduce atherosclerosis when given early in disease in animal models.7 Since the production of ROS are a mechanism by which the inflammatory response self-amplifies, a key question is whether apocynin has a beneficial effect in late stage disease to reduce plaque vulnerability by reducing endothelial cell adhesion molecules and subsequent recruitment of monocytes, and platelets or platelet microparticles which are recognized to have pro-inflammatory properties.10,11

In this study we used advanced in vivo imaging methods to investigate whether long-term administration of apocynin when administered at a stage of moderate to advanced disease would reduce vascular inflammation and arrest the progression of disease. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEU) molecular imaging of endothelial adhesion molecule expression and platelet adhesion were performed together with ultra-high frequency ultrasound assessment of vascular mechanical properties in a murine model of advanced atherosclerosis.

Methods

Study Design

The study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Oregon Health & Science University. Wild-type C57Bl/6 and double knockout (DKO) mice with age-dependent atherosclerosis produced by gene-targeted deletion of the LDL-receptor and Apobec-1 on a C57Bl/6 background were studied.12 Wild-type mice and DKO mice were studied at 30 wks of age (n=5 each), and DKO mice were also studied at 40 weeks of age with a preceding 10 wks of either no therapy (n=11), or apocynin (acetovanillone, Sigma) given in the drinking water at low dose (10 mg/kg/day, n=8) or high dose (50 mg/Kg/day, n=8). Drinking water concentrations were calibrated according to intake and changed daily to minimize light degradation. Measurements included transthoracic echocardiography; CEU molecular imaging for P-selectin, VCAM-1, and platelet GPIbα; ultrasound assessment of plaque size and vascular mechanical properties; and invasive arterial hemodynamics. Histology of the aorta was performed for each of the treatment groups at 40 wks.

Microbubble Preparation

Biotinylated, lipid-shelled decafluorobutane microbubbles were prepared by sonication of a gas-saturated aqueous suspension of distearoylphosphatidylcholine, polyoxyethylene-40-stearate, and distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine-PEG (2000) biotin. Microbubbles targeted to platelet GPIbα (MBGPIb), P-selectin (MBp), or VCAM-1 (MBv) were prepared by conjugating the following ligands to the shell surface as previously described: dimeric recombinant A1 domain (amino acids 445 to 709) of mouse von Willebrand factor (VWF), rat anti-mouse monoclonal IgG1 against P-selectin (RB40.34) or VCAM-1 (MK 2.7).13 Control microbubbles (MBc) were prepared using rat isotype control antibody (R3-34, Pharmingen Inc.). Microbubble concentration was measured by electrozone sensing (Multisizer III, Beckman-Coulter).

Flow-chamber Assessment of Microbubble-Platelet Interactions

To validate targeted attachment of MBGPIb, in vitro flow chamber studies were performed to assess microbubble-platelet interactions. Capillary tubes were incubated with fibrillar type-I collagen (100 μg/mL) for 1 hr then blocked with denatured BSA (5 mg/mL). Human whole blood anticoagulated with D-phenylalanyl-L-prolyl-L-arginine chloromethylketone (40 μM) was drawn through capillary tubes for 3 minutes at a wall shear rate of 500s−1 to form platelet-rich thrombi. Suspensions (3×106 mL−1) of MBGPIb and control microbubbles (either MBc or microbubbles bearing a non-binding mutant (substitution Gly561→Ser) of human VWF A1-domain of vWF [MBGPIb-mut]) were differentially labeled with the fluorophores DiI or DiO, mixed with either PBS or anticoagulated whole blood, and drawn through the flow chamber at shear rates of 300, 500 or 1000 s−1 for 3 min. Tubes were washed with PBS and the number of microbubbles attached was averaged from 10–15 randomly selected non-overlapping optical fields (0.09 mm−2) on fluorescent microscopy. Experiments were performed in triplicate for each condition

Molecular Imaging

Mice were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane (1.0 to 1.5%). Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEU) of the ascending aorta and proximal aortic arch was performed with a linear-array probe (Sequoia, Siemens Medical Systems) using a right parasternal window. Multipulse phase-inversion and amplitude-modulation imaging was performed at 7 MHz and a mechanical index (MI) of 0.97. Images were acquired 8 min after intravenous injection of targeted or control microbubbles (1×106 per injection) performed in random order. Signal from retained microbubbles was determined from the first frame obtained. As previously described,14 signal from the few freely-circulating microbubbles was eliminated by digital subtraction of several averaged frames obtained after complete destruction of microbubbles in the imaging field (Supplemental Figure A). Intensity was measured from a region-of-interest placed on the ascending aorta and proximal arch and extending into the origin of the brachiocephalic artery. Region selection was guided by fundamental 2-D imaging at 14 MHz acquired after each CEU imaging sequence.

Ultrasound Assessment of Plaque Size and Aortic Mechanical Properties

Plaque size was assessed by high-frequency (30MHz) ultrasound imaging (Vevo 770, VisualSonics Inc.) performed from a right parasternal window. Measurements of vessel wall thickness at lesion-prone sites of the lesser curvature of the aortic arch and the origin of the brachiocephalic artery (near wall) were made at end-diastole. M-mode imaging perpendicular to the mid-ascending aorta was performed and aortic strain was calculated as the change in systolic and diastolic diameter divided by diastolic diameter (ΔD/Ddia). A micromanometer (SPR-1000, Millar Instruments, Inc.) was inserted into the aorta via the carotid artery for arterial pressure measurement and aortic elastic modulus (εA) was calculated by:

where ΔP is pulse pressure expressed in 105 N·m−2. Pulse wave transit time (PTT) assessment of arterial stiffness was assessed by the time delay of the onset of systolic pressure rise measured by pulse-wave Doppler in the proximal ascending aorta and the femoral artery approximately 0.5 mm from the pudendoepigastric trunk, using the ECG as a time reference. Measurements were averaged for 3 cardiac cycles.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography (30 MHz) was performed using parasternal views. Left ventricular fractional shortening and percent area change were assessed in the mid-ventricular short-axis plane. Stroke volume was calculated by the product of left ventricle outflow tract (LVOT) area and LVOT time-velocity integral on pulsed-wave Doppler. Aortic centerline velocity was measured by pulsed-wave Doppler in the distal aortic arch.

Histology

Perfusion fixed short-axis sections from two sites, the mid-ascending aorta and arch just proximal to the brachiocephalic artery, were evaluated at 40 wks of age (n=5 animals for each treatment group). Masson’s trichrome stain was performed to assess the plaque area calculated by the vessel tissue area within the internal elastic lamina. Immunohistochemistry was performed using goat polyclonal primary antibodies against mouse Mac-2 (M3/38, eBioscience) for identifying monocytes and macrophages;15 or against GPIIb integrin (sc20234, Santa Cruz) for platelets; or rabbit polyclonal antibody against VCAM-1 (BS-0369r, Bioss Inc.). Species-appropriate ALEXAFluor-488, -555, or -594 secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used. Spatial extent of Mac-2 expression was quantified by using non-confocal microscopy which provided the optimal binary data for positive/negative staining using Image-J and a threshold of >2SD above of the tunica media intensity excluding the elastic lamina.16 Data were expressed as Mac-2-positive area within the internal elastic lamina and as a percentage of total plaque area determined using low-level green autofluorescence identification. Confocal fluorescent microscopy was used to identify platelets on the endothelial surface.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed on SPSS (version 16.0). All data were normally distributed and expressed as mean (±SD) unless otherwise stated. Comparisons between 30 wk wild-type and DKO mice, and of the 40 wk groups to 30 wk DKO mice were made with unpaired Students t-test (two-tailed). Comparisons between 30 wk mice and all three 40 wk DKO cohorts were made with one-way ANOVA and, when significant (p<0.05), post-hoc analysis with unpaired Students t-test and Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was performed. Comparisons of in vitro microbubble adhesion at different shear conditions were made with two-way ANOVA and, when significant (p<0.05) post-hoc analysis with paired t-tests.

Results

Blood Pressure and Left Ventricular Function

Arterial systolic and diastolic pressures in DKO mice at 30 wks of age were higher than in wild type mice, whereas pulse pressure was not significantly different (Table). In untreated DKO mice, arterial systolic pressure and diastolic pressure both increased between 30 and 40 wks of age. This increase was prevented by apocynin treatment in a dose-dependent fashion. Moreover, for the high-dose apocynin treatment group systolic arterial pressure and pulse pressure were lower at 40 wks than 30 wks of age.

Table.

Hemodynamic and Echocardiography Data (mean ±SD)

| Wild type 30 wk (n=5) | DKO 30 wk (n=5) | DKO 40 wk

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated Control (n=10) | Low-dose Apocynin (n=8) | High-dose Apocynin (n=6) | |||

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 97±3 | 108±3* | 120±5† | 107±4‡ | 101±7‡ |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 65±5 | 73±4* | 81±4† | 75±3‡ | 72±6‡ |

| Pulse Pressure (mm Hg) | 32±3 | 35±3 | 38±5 | 32±3‡ | 29±3†‡ |

| Fractional Shortening (%) | 39±2 | 38±4 | 43±6 | 44±5 | 41±4 |

| LVEF (%) | 70±3 | 68±5 | 74±7 | 76±7 | 70±5 |

| Stroke Volume (μL) | 37±2 | 34±6 | 38±5 | 36±4 | 41±5 |

| Aortic Internal Diameter (mm) | 1.15±0.17 | 1.31±0.04* | 1.45±0.09† | 1.44±0.04† | 1.43±0.10† |

| Aortic Peak Systolic Velocity (m/s) | 0.72±0.11 | 0.72±0.03 | 0.73±0.08 | 0.71±0.04 | 0.71±0.4 |

BP, blood pressure; DKO, double knockout mice; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction;

p<0.05 vs wild type;

p<0.05 vs DKO 30 wk.

p<0.05 vs untreated DKO group at 40 wks.

On echocardiography left ventricular fractional shortening, LVEF and stroke volume were not significantly different for wild type and DKO mice at 30 wks of age (Table). For DKO mice, there was a non-significant trend for an increase in these parameters between 30 wks and 40 wks of age but all were similar between treatment groups at 40 wks. Aortic internal diameter at 30 wks of age was greater for DKO compared to wild type mice and progressively increased by 40 wks of age in all treatment groups. Aortic peak systolic flow velocities were not different between treatment groups at 40 wks suggesting similar hemodynamic conditions and shear rates, which can potentially influence targeted microbubble attachment.

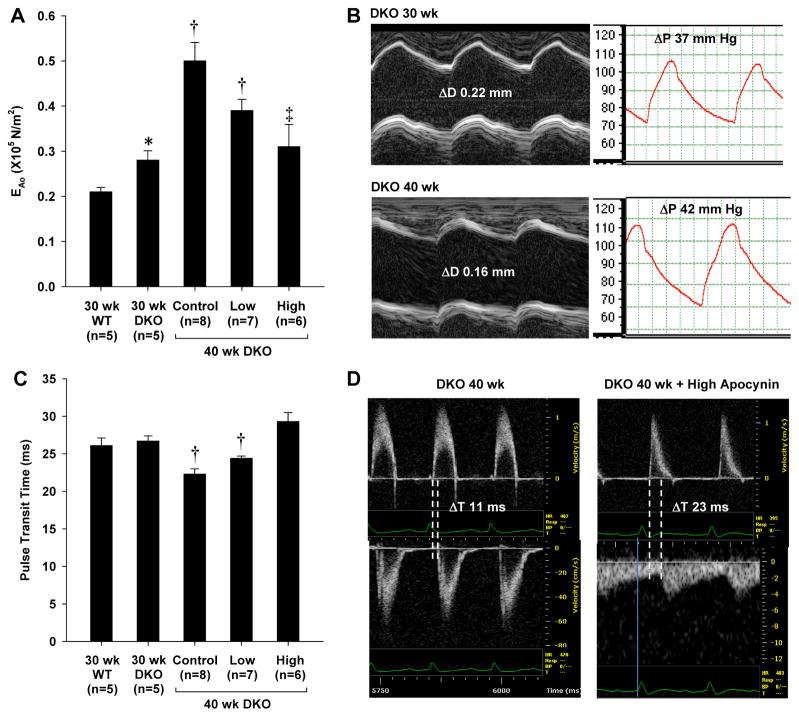

Aortic Mechanical Properties

Elastic modulus of the aorta (EAo) was significantly higher for DKO than wild type mice at 30 wks and significantly increased between 30 and 40 wks of age in untreated DKO mice (Figure 1A and 1B), indicating an age-dependent worsening of aortic elastic properties. The age-dependent increase in EAo was attenuated by apocynin. In the high-dose treatment cohort EAo in DKO mice at 40 wks was similar to that at 30 wks of age. Although PTT was not different between DKO and wild type mice at 30 wks of age, there was an age-dependent decrease in PTT in untreated DKO mice, indicating a reduction in vascular compliance (Figure 1C and 1D). The age-dependent decrease in PTT was attenuated by apocynin. Again PTT in the high-dose treatment cohort was similar to that in mice at 30 wks of age.

Figure 1.

(A) Elastic modulus (mean ±SEM) of the thoracic aorta (EAo) in wild type mice and DKO mice at baseline (30 wks) and at 40 wks after 10 wks of either no treatment (control) or apocynin given at low- and high-dose. (B) Examples of source data for from a non-treated animal illustrating age-dependent worsening of EAo as a result of both an increase in the aortic pulse pressure (ΔP) and a reduction in the systolic aortic diameter change (ΔD) from M-mode echocardiography. (C) Pulse transit time (mean ±SEM) in wild type mice and DKO mice at baseline and at 40 wks. (D) Examples of pulse-wave spectral Doppler data from an untreated and high-dose apocynin-treated DKO mouse at 40 wks illustrating differences in pulse transit time measured as the time delay (ΔT) for the onset of systolic flow from the ascending aorta (top) to the femoral artery (bottom). *p<0.05 vs. 30 wk wild type; †p<0.05 vs.30 wk DKO; ‡p<0.05 versus untreated (control) 40 wk DKO.

In vitro Assessment of Targeted Microbubble Attachment

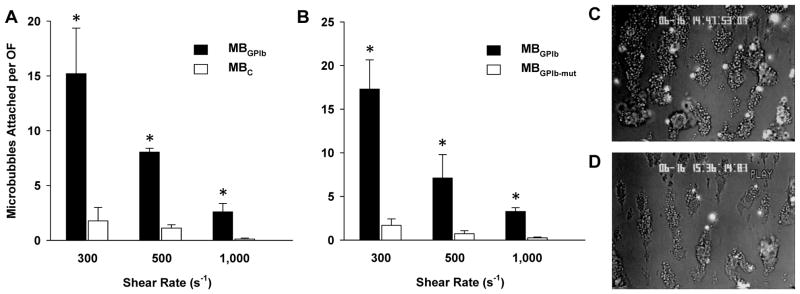

Binding properties have previously been characterized for microbubble molecular imaging agents targeted to P-selectin (MBp) and VCAM-1 (MBv),13,17 but not for MBGPIb Accordingly flow chamber studies were performed to assess in vitro microbubble-platelet interactions. Across a range of shear rates, attachment of MBGPIb in PBS to platelet aggregates was significantly greater than for control microbubbles lacking a targeting ligand (Figure 2A). Attachment of MBGPIb was shear-dependent. When suspended in whole blood, attachment of MBGPIb was also significantly greater than for microbubbles bearing a mutated non-binding form of VWF A1-domain (MBGPIb-mut) (Figure 2B). Attachment for MBGPIb was almost exclusively to platelet aggregates (Figure 2C and 2D). Platelet attachment for MBGPIb when suspended in whole blood was similar to that when suspended in PBS, indicating minimal competitive inhibition from plasma VWF or from other endogenous GPIbα ligands.

Figure 2.

Mean (±SEM) number of microbubbles attached to platelet complexes per optical field (OF) for flow chamber studies when comparing microbubbles targeted to GPIbα (MBGPIb) to either (A) control microbubbles not bearing a ligand (MBC) suspended in PBS; or (B) control microbubbles bearing a mutated non-binding ligand (MBIb-mut) suspended in whole blood. Examples show fluorescent MBGPIb attaching to platelet complexes at shear rates of (C) 300 s−1 and (D) 1,000 s−1.

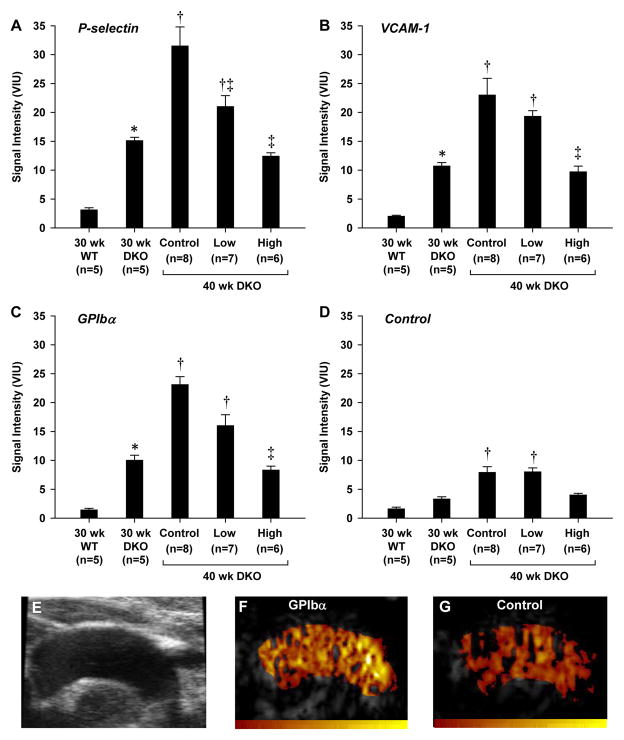

Molecular Imaging of Inflammation and Platelet Adhesion

Molecular imaging signal for P-selectin, VCAM-1, and platelet GPIbα were all much greater (>5-fold higher) in DKO than wild type mice at 30 wks of age (Figure 3). In untreated DKO mice, signal for all three targets had increased by more than 2-fold between 30 and 40 weeks of age. At 40 wks of age, P-selectin, VCAM-1 and platelet GPIbα molecular imaging signal were all reduced in a dose-dependent fashion by apocynin treatment. Signal in high-dose apocynin-treated DKO mice at 40 weeks was not significantly different to that measured in 30 wk DKO mice. Signal for all targeted agents in the untreated DKO mice at 30 and 40 wks was significantly greater (p<0.01) than signal from control non-targeted microbubbles.

Figure 3.

(A to D) Molecular imaging signal (mean ±SEM) for P-selectin, VCAM-1, or GPIbα, and for control non-targeted microbubbles. *p<0.05 vs. 30 wk wild type; †p<0.05 vs. 30 wk DKO; ‡p<0.05 versus untreated (control) 40 wk DKO. (E) Example from an untreated 40 wk DKO mouse of a 2-D ultrasound image of the aortic arch used to define regions-of-interest; and CEU molecular imaging from the same mouse after injection of either (F) GPIbα-targeted or (G) control microbubbles (color scale at bottom). As previously described,17 an ultrasound beam elevation (out-of-plane) dimension larger than the aortic diameter produced volume averaging and extension of molecular imaging signal enhancement into the apparent “lumen”. Illustration of method for background-subtraction are provided in Supplemental Figure A.

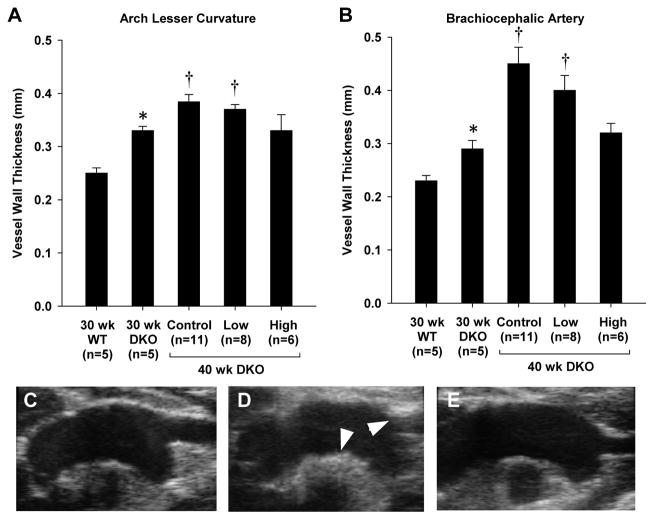

Plaque Size and Content

On high-frequency ultrasound, vessel thickness at the lesion-prone sites of the lesser curvature of the aorta and the proximal brachiocephalic artery was greater for DKO than wild type mice at 30 weeks of age (Figure 4). In DKO mice, vessel wall thickness increased between 30 and 40 wks of age consistent with the described age-dependent worsening of atherosclerosis in the DKO model.12,14 Discrete raised plaques could be identified in the brachiocephalic artery in all untreated animals at 40 wks of age. In DKO mice at 40 wks, apocynin prevented the increase in vessel thickness only when given at the high dose which resulted in vessel thickness similar to that measured at 30 wks.

Figure 4.

Vessel thickness (mean ±SEM) measured by high-frequency 2-D ultrasound imaging of the aortic arch measured at (A) the lesser curvature of the aortic arch, and (B) at the origin of the brachiocephalic artery. Images illustrate examples obtained from DKO mice (C) at 30 wks, (D) at 40 wks without treatment, or (E) at 40 wks with high-dose apocynin. Arrows illustrate regions of thickening at the lesser curvature of the arch and at the origin of the brachiocephalic artery. *p<0.05 vs. 30 wk wild type; †p<0.05 vs.30 wk DKO; ‡p<0.05 versus untreated (control) 40 wk DKO.

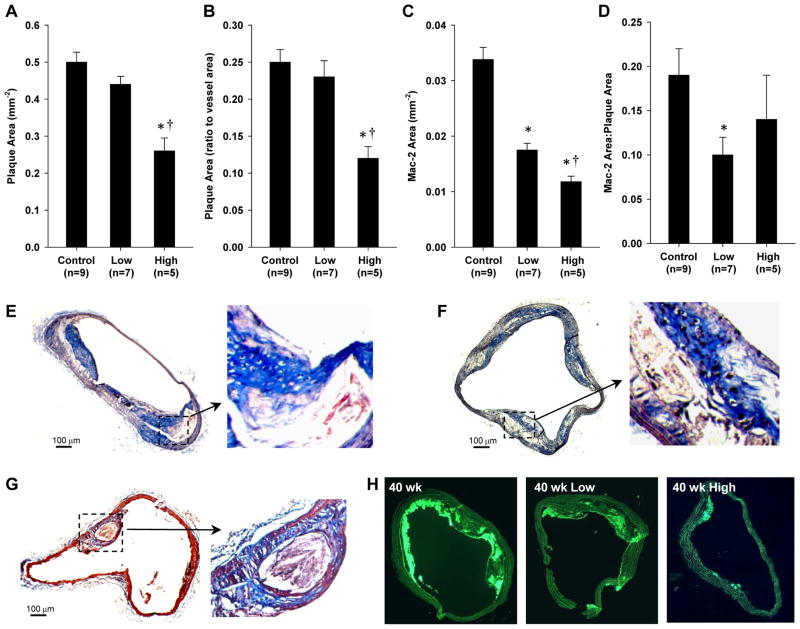

Histology in untreated DKO mice at 40 wks of age demonstrated atherosclerotic lesions with abundant Mac-2-positive cells (monocytes and macrophages) encroaching well into the aortic lumen in all mice (Figure 5). Consistent with ultrasound imaging results, plaque size by histology in 40 wk DKO mice was significantly reduced only in the high-dose apocynin treatment group (Figure 5A and 5B). In this group, however, discrete raised plaques were still observed (Figure 5G). Although low-dose apocynin did not reduce plaque area by ultrasound or histology, it did reduce monocyte and macrophage infiltration (Figure 5C). The degree to which macrophage infiltration was reduced was even greater for the high-dose group. Because plaque size was substantially reduced only in the high-dose group, monocyte and macrophage infiltration as a percentage of total plaque area was not different for the low-dose and high-dose apocynin groups (Figure 5D). Immunohistochemistry for GPIIb revealed the presence of platelets on the endothelial cell surface (Figure 6). Regions where site-density of platelets on the endothelial surface was high were seen only in the untreated mice. Interestingly, GPIIb staining was occasionally detected deep within large complex plaques in untreated mice. Staining for VCAM-1 confirmed a reduction in the spatial extent of VCAM-1 staining on both the endothelial surface and also within the plaque.

Figure 5.

(A and B) Mean (±SEM) plaque area in absolute terms and expressed as a ratio to the total vessel area for DKO mice at 40 wks of age. (C and D) Mean (±SEM) area staining positive for Mac-2 in absolute terms and expressed as a ratio to total plaque area. Histology illustrates plaque formation on Masson’s trichrome staining from: (D and E) two separate untreated 40 wk DKO mice, and (F) a high-dose apocynin-treated mouse. (G) Examples of Mac-2 staining illustrating differences in monocyte/macrophage accumulation at 40 wks in the different cohorts. Control staining staining conditions are provided in Supplemental Figure B. *p<0.05 vs. untreated control; and †p<0.05 vs. untreated controls and low-dose.

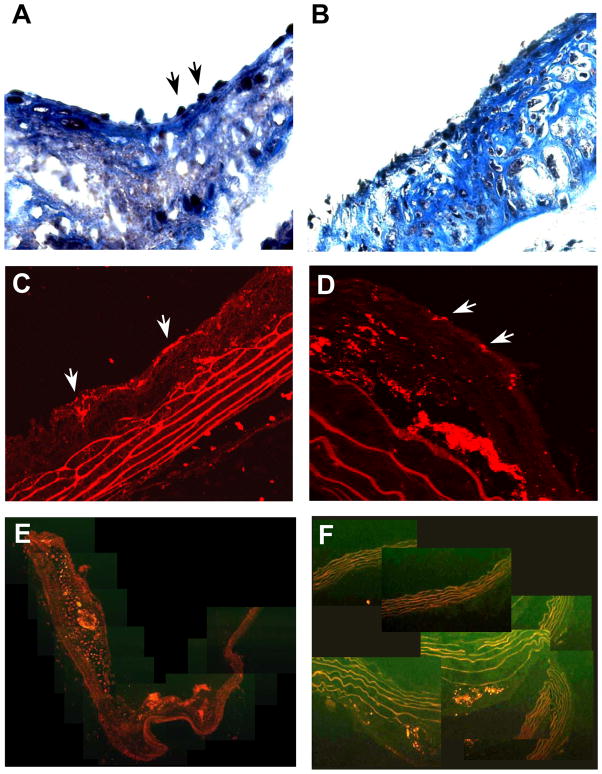

Figure 6.

(A and B) Histology with Masson’s trichrome illustrating inflammatory cells or platelets (arrows) adherent to the endothelial surface of plaques from two separate untreated 40 wk DKO mice. (C and D) Examples of immunofluorescent histology for GPIIb from two separate mice confirming the presence of platelets (arrows) on the endothelial surface and also within the plaque milieu. Composite images of VCAM-1 immunofluorescent staining from (E) an untreated 40 wk DKO mouse, and (F) a high-dose apocynin treated mouse.

Discussion

In this study, state-of-the-art non-invasive imaging methods for characterizing vascular molecular, ultrastructural, and elastic phenotype in vivo were employed to evaluate the effect of prolonged therapy with the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin. Our results indicate that prolonged treatment with apocynin when initiated at a mid to late stage of atherosclerotic disease: (a) prevented the progressive worsening of mechanical elastic properties of large arteries, (b) arrested any further increases in endothelial activation, (c) reduced platelet adhesion and monocyte infiltration, and (d) prevented plaque growth when given at high dose.

Oxidative stress is a key factor involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and, in many respects, is a self-amplifying process. The local vascular production of ROS such as superoxide, hydroxyl radicals, and hydrogen peroxide is thought to be important for promoting the advancement of disease from fatty streak to unstable plaque.1,2 Oxidative stress is an important regulator of pro-inflammatory gene expression mediated largely through the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB).4 There is strong evidence that through these mechanisms oxidative stress will increase expression of endothelial cell adhesion molecules such as P-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1; and production of pro-inflammatory chemokines.4,9,18,19 It is also well established that inactivation of nitric oxide (NO) by ROS can lead to acceleration of atherosclerosis and susceptibility to atherothrombotic events by interfering with NO’s anti-inflammatory, anti-platelet, and anti-proliferative effects.2

Self-amplification of oxidative stress in atherosclerosis has been attributed to the stimulation of the inflammatory cascade which itself is a source of ROS. However, it is increasingly evident that ROS generation is not solely from monocytes and foam cells. Many of the resident vascular cells such as endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts possess membrane-bound NADPH oxidase which serves as a major source for superoxide production in atherosclerosis.6,7 Again, self-amplifying mechanisms can be identified whereby many pro-inflammatory cytokines, thrombin, and angiotensin II further activate NADPH oxidase in vascular cells.1,20–22 The role of NADPH oxidase specifically in the development of atherosclerosis is strongly supported by the observation that gene-deletion of the p47phox subunit of the NADPH oxidase complex in apolipoprotein-E-deficient mice reduces atherosclerotic lesion size in the descending aorta.8

In this study, we studied whether oral treatment with apocynin, an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, could arrest the progression of atherosclerosis when initiated at mid to late-stage. Apocynin is an α-methoxyphenol extract from several plant sources that has been shown to have several biologic effects which include the prevention of NADPH oxidase assembly by inhibiting membrane tanslocation of the p47phox and gp91phox subunits.7 In vitro studies have demonstrated that reduction of ROS production from NADPH oxidase reduces endothelial VCAM-1, monocyte-endothelial interactions, platelet adhesion and smooth muscle cell proliferation in response to various stimuli.9,23,24 Apocynin specifically has been shown to reduce selectin and VCAM-1 expression, and platelet adhesion in vivo studies of acute inflammatory lung injury.25 However, there are few studies that have examined the effect of apocynin in atherosclerosis. Unpublished data has reported that apocynin when given at the time of initiation of a hypercholesterolemic diet in New Zealand white rabbits can attenuate atherosclerotic plaque development independent of any effects on lipid lowering.26

In order to mimic a clinically-relevant situation, we chose to introduce apocynin after allowing sufficient time for the development of advanced lesions in a gene-targeted model of age-dependent atherosclerosis in mice. Our data indicate that apocynin can arrest plaque progression. These data complement prior studies showing a reduction in plaque size with prolonged inhibition of NADPH oxidase in ApoE−/− mice.19 We found that apocynin also reduced total plaque macrophage content. Although both plaque size and macrophage content were lower in the high-dose apocynin group, we cannot say for sure that this represents conversion to a more stable phenotype since the ratio of monocytes to plaque area was significantly lower statistically from controls only in the low-dose group.

Molecular imaging data was useful for defining at least one potential mechanism by which inflammatory cell accumulation was reduced. Apocynin appeared to prevent the progressive and marked increase in the expression of two key endothelial adhesion molecules involved in monocyte recruitment, P-selectin and VCAM-1. The use of CEU and targeted microbubbles with a mean diameter of approximately 2 μm is an advantage in that allowed us to examine adhesion molecule expression only on the luminal surface. These results indicate that apocynin had a beneficial effect in part through interrupting one of the main mechanisms by which ROS is thought to contribute in a self-amplifying manner to the pathogenesis of unstable atherosclerotic disease.

In order to assess platelet adhesion in this study, a new probe for molecular imaging of platelets with CEU was developed. A recombinant protein with the amino acid sequence corresponding to the A-1 domain of mouse VWF was used as a targeting ligand since its interaction with the platelet GPIbα receptor can occur despite high shear stresses.27 Our flow chamber studies indicated that this targeting ligand when displayed on microbubbles is not substantially affected by potential competitive inhibitors in plasma.

There were several reasons for examining platelet-endothelial interactions in this study besides simply evaluating apocynin’s effect on thrombotic susceptibility. Platelet or platelet microparticle interactions with the vessel wall play a role in promoting inflammation in atherosclerosis through several mechanisms. Platelets are a source for local release of many pro-inflammatory factors including C-C motif chemokines (RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β) and platelet factor-4.10,28,29 Platelets may also contribute to endothelial activation in atherosclerosis by CD40L-CD40 signaling,30 and can potentiate the adhesive interactions between monocyte and the activated endothelium.31,32 Platelet adhesion to the intact endothelium in DKO mice was demonstrated both by GPIIb immunohistochemistry in this study and by electron microscopy in previous studies.33 These interactions were prevented in a dose-dependent fashion by apocynin, which may have also contributed to the slower progression of disease and reduced macrophage infiltrate in the treated animals.

The improvement in the arterial elastic properties and blood pressure with apocynin we observed is likely multifactorial. As reviewed elsewhere,1,34 oxidative stress in animal models and in humans, even in the absence of atherosclerosis, has been strongly linked to impaired arterial elastic properties and hypertension. ROS may contribute to hypertension and vascular stiffness by reducing NO bioavailability, direct vasoconstrictor effects, and promoting vascular remodeling and medial hyperplasia. It is also now recognized that angiotensin II exerts its effects on blood pressure and vascular remodeling in part through activation of NADPH oxidase, and that both angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blocking agents improve blood pressure in part through reducing ROS production.1,35 Hence, it likely that the improvements in hemodynamics and elastic properties with apocynin therapy did not simply reflect the beneficial vascular effects of reducing the atherosclerotic burden.

There are several limitations of this study that deserve attention. First, we did not measure plasma apocynin levels. Our doses were guided by previous studies examining cardiovascular effects of apocynin and were several orders of magnitude lower than the reported LD50.7 Although we have reported P-selectin signal as a marker for endothelial activation, a portion of this signal may have been attributable to adherent platelets. This possibility does not necessarily detract from the overall message that apocynin decreases endothelial inflammatory phenotype. P-selectin immunhistochemistry was not performed since this molecule is stored pre-formed within endothelial Weibel-Palade bodies and, accordingly, its presence on histology does not necessarily reflect luminal expression. We also did not specifically assess the effects of apocynin on monocyte function largely because previous studies have suggested that macrophage adhesive function and migration are not affected in p47phox−/− mice. On molecular imaging, although control microbubble signal was very low, it followed a similar pattern as targeted agents with an increasing with age in the DKO mice and a reduction with high-dose apocynin. This likely represents low-level interaction of lipid microbubbles with leukocytes on the vascular surface or direct complement-mediated interactions with the vascular endothelium.36,37 As we have previously described, although there are regions where atherosclerosis becomes particularly severe in this mouse model, beam volume-averaging precludes us from making any conclusions on regional heterogeneity of molecular imaging signal.14 Finally, these studies do not necessarily confirm that the beneficial effects of apocynin are all attributable to its effect on NADPH oxidase.

In summary, our results have demonstrated several beneficial vascular effects of apocynin when administrated relatively late in the development of atherosclerotic disease. Apocynin arrests progressive worsening of atherosclerotic disease in terms of plaque severity, degree of endothelial activation, and number of moncytes in the vessel wall;, and may be a potential therapeutic approach to reducing risk for clinical events related to unstable atherosclerotic disease.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

Oxidative stress plays a critical role in the development of atherosclerosis and complications such as acute coronary syndrome and stroke. Results from clinical trials using anti-oxidants which are designed to quench reactive oxygen species have been disappointing. In this study, we examined the effects of inhibiting one of the main enzymatic sources for oxidative stress in atherosclerosis, NADPH oxidase. Ultrasound molecular imaging of endothelial inflammatory activation (VCAM-1 and P-selectin expression) and platelet adhesion (GPIb signal) were used together with advanced ultrasound imaging of vascular stiffness in a mice with atherosclerosis treated with apocynin, an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase. When given at an intermediate stage of atherosclerosis for 10 weeks, apocynin in a dose dependent fashion reduced endothelial activation and platelet adhesion. We believe these effects were in part responsible for the reduction in plaque area over time, reduction in macrophage number, and improvement in vascular mechanical properties observed with apocynin treatment. These results suggest that potent anti-oxidant therapies aimed at preventing production of reactive oxygen species may be effective at arresting atherosclerosis. They also highlight that molecular imaging may be a valuable asset for the pre-clinical assessment of new therapies for atherosclerosis, and possibly be used in the future for identifying patients who will benefit from these new therapies according to disease phenotype.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

Dr. Liu is supported by a grant (81101053) from the National Science Foundation of China. Dr. Davidson is supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32-HL094294). This work was supported by grants R01-DK063508, R01-HL078610, RC1-HL100659, and R01-HL111969 (Dr. Lindner); R01HL101972 (Dr. McCarty); and P01-HL31950, R01-HL42846, and P01-HL78784 (Dr. Ruggeri) from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Ruggeri is also supported from a grant from the Roon Research center on Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis. Dr. Kaufmann is supported by grants 32323B, 123819, and 3232B0-141603 from the Swiss National Science Foundation. Mr. Tormoen is supported by American Heart Association (12PRE11930019). Dr. McCarty is an American Heart Association Established Investigator.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Madamanchi NR, Vendrov A, Runge MS. Oxidative stress and vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:29–38. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000150649.39934.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lubos E, Handy DE, Loscalzo J. Role of oxidative stress and nitric oxide in atherothrombosis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:5323–5344. doi: 10.2741/3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolin MS. Interactions of oxidants with vascular signaling systems. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1430–1442. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.6.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunsch C, Medford RM. Oxidative stress as a regulator of gene expression in the vasculature. Circ Res. 1999;85:753–766. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.8.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman JE. Oxidative stress and platelets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:s11–16. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babior BM. Nadph oxidase: An update. Blood. 1999;93:1464–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu J, Weiwer M, Linhardt RJ, Dordick JS. The role of the methoxyphenol apocynin, a vascular nadph oxidase inhibitor, as a chemopreventative agent in the potential treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2008;6:204–217. doi: 10.2174/157016108784911984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barry-Lane PA, Patterson C, van der Merwe M, Hu Z, Holland SM, Yeh ET, Runge MS. P47phox is required for atherosclerotic lesion progression in apoe(−/−) mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1513–1522. doi: 10.1172/JCI11927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki Y, Wang W, Vu TH, Raffin TA. Effect of nadph oxidase inhibition on endothelial cell elam-1 mrna expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;184:1339–1343. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Hundelshausen P, Weber KS, Huo Y, Proudfoot AE, Nelson PJ, Ley K, Weber C. Rantes deposition by platelets triggers monocyte arrest on inflamed and atherosclerotic endothelium. Circulation. 2001;103:1772–1777. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massberg S, Brand K, Gruner S, Page S, Muller E, Muller I, Bergmeier W, Richter T, Lorenz M, Konrad I, Nieswandt B, Gawaz M. A critical role of platelet adhesion in the initiation of atherosclerotic lesion formation. J Exp Med. 2002;196:887–896. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell-Braxton L, Veniant M, Latvala RD, Hirano KI, Won WB, Ross J, Dybdal N, Zlot CH, Young SG, Davidson NO. A mouse model of human familial hypercholesterolemia: Markedly elevated low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and severe atherosclerosis on a low-fat chow diet. Nat Med. 1998;4:934–938. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindner JR, Song J, Christiansen J, Klibanov AL, Xu F, Ley K. Ultrasound assessment of inflammation and renal tissue injury with microbubbles targeted to p-selectin. Circulation. 2001;104:2107–2112. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufmann BA, Carr CL, Belcik JT, Xie A, Yue Q, Chadderdon S, Caplan ES, Khangura J, Bullens S, Bunting S, Lindner JR. Molecular imaging of the initial inflammatory response in atherosclerosis: Implications for early detection of disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:54–59. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.196386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu FT, Hsu DK, Zuberi RI, Kuwabara I, Chi EY, Henderson WR., Jr Expression and function of galectin-3, a beta-galactoside-binding lectin, in human monocytes and macrophages. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1016–1028. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/docs/index.html

- 17.Kaufmann BA, Sanders JM, Davis C, Xie A, Aldred P, Sarembock IJ, Lindner JR. Molecular imaging of inflammation in atherosclerosis with targeted ultrasound detection of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Circulation. 2007;116:276–284. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.684738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tummala PE, Chen XL, Medford RM. Nf- kappa b independent suppression of endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 gene expression by inhibition of flavin binding proteins and superoxide production. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1499–1508. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cayatte AJ, Rupin A, Oliver-Krasinski J, Maitland K, Sansilvestri-Morel P, Boussard MF, Wierzbicki M, Verbeuren TJ, Cohen RA. S17834, a new inhibitor of cell adhesion and atherosclerosis that targets nadph oxidase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1577–1584. doi: 10.1161/hq1001.096723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patterson C, Ruef J, Madamanchi NR, Barry-Lane P, Hu Z, Horaist C, Ballinger CA, Brasier AR, Bode C, Runge MS. Stimulation of a vascular smooth muscle cell nad(p)h oxidase by thrombin. Evidence that p47(phox) may participate in forming this oxidase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19814–19822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Keulenaer GW, Alexander RW, Ushio-Fukai M, Ishizaka N, Griendling KK. Tumour necrosis factor alpha activates a p22phox-based nadh oxidase in vascular smooth muscle. Biochem J. 1998;329 (Pt 3):653–657. doi: 10.1042/bj3290653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ushio-Fukai M, Zafari AM, Fukui T, Ishizaka N, Griendling KK. P22phox is a critical component of the superoxide-generating nadh/nadph oxidase system and regulates angiotensin ii-induced hypertrophy in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23317–23321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wedgwood S, Dettman RW, Black SM. Et-1 stimulates pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation via induction of reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L1058–1067. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.5.L1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber C, Erl W, Pietsch A, Strobel M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Weber PC. Antioxidants inhibit monocyte adhesion by suppressing nuclear factor-kappa b mobilization and induction of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in endothelial cells stimulated to generate radicals. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:1665–1673. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.10.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Impellizzeri D, Esposito E, Mazzon E, Paterniti I, Di Paola R, Bramanti P, Cuzzocrea S. Effect of apocynin, a nadph oxidase inhibitor, on acute lung inflammation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81:636–648. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holland JA, Johnson DK. Prevention of atherosclerosis using NADPH oxidase inhibitors. 5,902,831. US Patent. 1999

- 27.Ruggeri ZM, Orje JN, Habermann R, Federici AB, Reininger AJ. Activation-independent platelet adhesion and aggregation under elevated shear stress. Blood. 2006;108:1903–1910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-011551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huo Y, Schober A, Forlow SB, Smith DF, Hyman MC, Jung S, Littman DR, Weber C, Ley K. Circulating activated platelets exacerbate atherosclerosis in mice deficient in apolipoprotein e. Nat Med. 2003;9:61–67. doi: 10.1038/nm810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weber C. Platelets and chemokines in atherosclerosis: Partners in crime. Circ Res. 2005;96:612–616. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000160077.17427.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henn V, Slupsky JR, Grafe M, Anagnostopoulos I, Forster R, Muller-Berghaus G, Kroczek RA. Cd40 ligand on activated platelets triggers an inflammatory reaction of endothelial cells. Nature. 1998;391:591–594. doi: 10.1038/35393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuijper PH, Gallardo Torres HI, Houben LA, Lammers JW, Zwaginga JJ, Koenderman L. P-selectin and mac-1 mediate monocyte rolling and adhesion to ecm-bound platelets under flow conditions. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:467–473. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Gils JM, Zwaginga JJ, Hordijk PL. Molecular and functional interactions among monocytes, platelets, and endothelial cells and their relevance for cardiovascular diseases. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:195–204. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0708400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarty OJ, Conley RB, Shentu W, Tormoen GW, Zha D, Xie A, Qi Y, Zhao Y, Carr C, Belcik T, Keene DR, de Groot PG, Lindner JR. Molecular imaging of activated von willebrand factor to detect high-risk atherosclerotic phenotype. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:947–955. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel RS, Al Mheid I, Morris AA, Ahmed Y, Kavtaradze N, Ali S, Dabhadkar K, Brigham K, Hooper WC, Alexander RW, Jones DP, Quyyumi AA. Oxidative stress is associated with impaired arterial elasticity. Atherosclerosis. 2011;218:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warnholtz A, Nickenig G, Schulz E, Macharzina R, Brasen JH, Skatchkov M, Heitzer T, Stasch JP, Griendling KK, Harrison DG, Bohm M, Meinertz T, Munzel T. Increased nadh-oxidase-mediated superoxide production in the early stages of atherosclerosis: Evidence for involvement of the renin-angiotensin system. Circulation. 1999;99:2027–2033. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.15.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindner JR, Coggins MP, Kaul S, Klibanov AL, Brandenburger GH, Ley K. Microbubble persistence in the microcirculation during ischemia/reperfusion and inflammation is caused by integrin- and complement-mediated adherence to activated leukocytes. Circulation. 2000;101:668–675. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.6.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson DR, Tsutsui JM, Xie F, Radio SJ, Porter TR. The role of complement in the adherence of microbubbles to dysfunctional arterial endothelium and atherosclerotic plaque. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.