Abstract

Neuronal cell death via apoptosis or necrosis underlies several devastating neurodegenerative diseases associated with aging. Mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from oxidative or nitrosative stress often acts as an initiating stimulus for intrinsic apoptosis or necrosis. These events frequently occur in conjunction with imbalances in the mitochondrial fission and fusion equilibrium, although the cause and effect relationships remain elusive. Here, we demonstrate in primary rat cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) that oxidative or nitrosative stress induces an N-terminal cleavage of optic atrophy-1 (OPA1), a dynamin-like GTPase that regulates mitochondrial fusion and maintenance of cristae architecture. This cleavage event is indistinguishable from the N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 observed in CGNs undergoing caspase-mediated apoptosis (Loucks et al., 2009) and results in removal of a key lysine residue (K301) within the GTPase domain. OPA1 cleavage in CGNs occurs coincident with extensive mitochondrial fragmentation, disruption of the microtubule network, and cell death. In contrast to OPA1 cleavage induced in CGNs by removing depolarizing extracellular potassium (5K apoptotic conditions), oxidative or nitrosative stress-induced OPA1 cleavage caused by complex I inhibition or nitric oxide, respectively, is caspase-independent. N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 is also observed in vivo in aged rat and mouse midbrain and hippocampal tissues. We conclude that N-terminal cleavage and subsequent inactivation of OPA1 may be a contributing factor in the neuronal cell death processes underlying neurodegenerative diseases, particularly those associated with aging. Furthermore, these data suggest that OPA1 cleavage is a likely convergence point for mitochondrial dysfunction and imbalances in mitochondrial fission and fusion induced by oxidative or nitrosative stress.

Keywords: Mitochondrial dynamics, Apoptosis, Aging, Complex I, Reactive oxygen species, Nitric oxide, Caspases

1. Introduction

It is increasingly clear that aging and neurodegeneration are mechanistically linked through oxidative or nitrosative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and disruption of the mitochondrial fission and fusion equilibrium. Aging is often reported as the greatest risk factor for the onset of sporadic neurodegenerative diseases and this correlation is largely attributed to mitochondrial dysfunction (Bossy-Wetzel et al., 2003; Lin and Beal, 2006). However, the mechanistic interrelationships between oxidative or nitrosative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and alterations in mitochondrial fission and fusion are complex and not well defined. Therefore, identifying molecular events which link two or more of these factors to neuronal cell death will help unravel the pathological basis of the association between neurodegeneration and aging.

The aberrant production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), or deficits in endogenous antioxidant or free radical scavenging systems, appear to be critical factors in neurodegenerative disorders and aging. Evidence indicates that increased oxidative or nitrosative damage through both ROS and RNS in the substantia nigra likely plays a significant role in dopaminergic cell death in Parkinson’s disease (PD)(Jenner, 2003). In particular, complex I inhibition and the associated mitochondrial oxidative stress are pathogenic in PD and have led to the development of several neurotoxin models of this disease including MPTP and rotenone (Przedborski and Vila, 2003; Sherer et al., 2007). Studies of post-mortem Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain tissue also reveal the adverse effects of ROS and RNS, including lipid peroxidation, increased protein carbonyls, and enhanced peroxynitrite-mediated damage (Lin and Beal, 2006; Smith et al., 1997). Similarly, increased protein carbonyls, 3-nitrotyrosine, and lipid peroxidation have been observed in spinal cord motor neurons and CSF of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Barber and Shaw, 2010). Importantly, increased oxidative damage as a result of mitochondrial dysfunction also demonstrated in aging, indicating a potential pathway where aging and neurodegeneration converge (Bossy-Wetzel et al., 2003).

Mitochondria are essential organelles that participate in diverse functions such as ATP production, buffering of intracellular calcium, maintenance of cell survival through sequestration of cytochrome c, and apoptotic signaling through the release of pro-apoptotic factors (Ow et al., 2008; Sheridan et al., 2010). Mitochondria exist in a dynamic state and their proper function relies on a critical balance of fission and fusion events (Detmer and Chan, 2007). Impairment of this delicate balance can lead to decreased mitochondrial respiration rates and increased ROS production, leading to a catastrophic cycle of further damage and dysfunction (Chen et al., 2005; Knott et al., 2008). Neurons are particularly susceptible to impairments in mitochondrial dynamics due to their increased energy demands (Detmer and Chan, 2007; Knott et al., 2008). Accordingly, a fundamental link between mitochondrial impairment and neurodegeneration is heavily substantiated by current literature (Lin and Beal, 2006; Perry et al., 2002).

Several proteins of the dynamin family of large GTPases are responsible for mitochondrial fission and fusion, and disruptions of the fission and fusion machinery have been linked to neurodegeneration (Cho et al., 2010; Knott et al., 2008). Optic atrophy-1 (OPA1) is a member of this GTPase family and is a major player in fusion of the inner mitochondrial membrane and maintenance of cristae architecture, events which are orchestrated through oligomerization of differentially processed forms of OPA1. Oligomerization of OPA1 is necessary for sequestration of cytochrome c in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, and disruption in this function is shown to induce the intrinsic apoptotic cascade (Cipolat et al., 2004; Olichon et al., 2003). OPA1 is highly expressed in retinal tissue during development and into adulthood (Aijaz et al., 2004). The importance of proper OPA1 function is underscored by its involvement in the neurodegenerative condition, autosomal dominant optic atrophy type 1, which involves mutations in the gene encoding for OPA1 (Delettre et al., 2000). Individuals with this disease develop progressive blindness as a result of degeneration of retinal ganglion cells and their axons that comprise the optic nerve. A subset of patients exhibit additional multi-system neurological deficits as a result of mitochondrial impairment (Amati-Bonneau et al., 2009). In vitro studies to delineate possible mechanisms by which OPA1 mutations cause disease have indicated that down regulation or loss-of-function of OPA1 results in mitochondrial fragmentation and disruption of the cristae architecture. Although the importance of OPA1 expression in retinal tissue is pathologically relevant, additional neuronal expression of OPA1 has been demonstrated in the motor cortex, the frontal brain, the spinal cord, and the cerebellar cortex (Aijaz et al., 2004; Delettre et al., 2001; Misaka et al., 2002). The importance of OPA1 expression in neurological function is evident, yet its expression in non-neural tissue indicates a widespread function.

OPA1 exists as eight alternatively-spliced variants (Delettre et al., 2001). Upon import into the mitochondria, the mitochondrial targeting sequence is cleaved by mitochondrial processing peptidases to produce a long (L) isoform (Ishihara et al., 2006). Within the mitochondria, OPA1 undergoes further cleavage at several positions to yield soluble, short (S) isoforms. Here, processing of OPA1 becomes more complex. OPA1 is constitutively cleaved into a short isoform by the ATP-dependent metalloprotease YME1L1 (Griparic et al., 2007; Song et al., 2007). Additional cleavage events are mediated by the m-AAA proteases paraplegin and AFG3L1 -2 during loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, and the presenilin-associated rhomboid-like (PARL) protease during apoptosis (Cipolat et al., 2006; Guillery et al., 2008; Song et al., 2007). The overlap in actions of these proteases indicates a potential redundancy in their functions; this is highlighted by the observation that effective siRNA knock-down of any one of these proteases does not abolish OPA1 processing (Griparic et al., 2007; Guillery et al., 2008).

Differential processing of OPA1 splice variants results in at least five distinct isoforms (denoted “a”-“e”), all of which are visible by Western blotting. We previously reported the appearance of a novel, smaller OPA1 cleavage product (denoted “f”) upon induction of apoptosis in primary cultures of rat cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs). This N-terminal cleavage event removes a critical portion of the GTPase domain including K301 and, therefore, GTPase activity would be lost and OPA1 rendered non-functional (Loucks et al., 2009). This is evident in the observed fragmentation of the mitochondrial network coincident with N-terminal OPA1 cleavage. In CGNs, the N-terminal OPA1 cleavage induced during apoptosis was demonstrated to be caspase-dependent, yet in vitro experiments revealed that caspases were not able to directly cleave OPA1. Our current studies reveal that this N-terminal OPA1 cleavage also occurs during oxidative or nitrosative stress-induced neuronal cell death, but in a caspase-independent manner. This particular cleavage event has yet to be identified within a specific neurodegenerative condition; however, we demonstrate that N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 occurs spontaneously with advancing age in rat and mouse midbrain and hippocampal tissues. These findings further connect mitochondrial dysfunction to aging, a principle risk factor for neurodegeneration.

2. Results

2.1 5K-induced CGN apoptosis triggers caspase-dependent N-terminal OPA1 cleavage

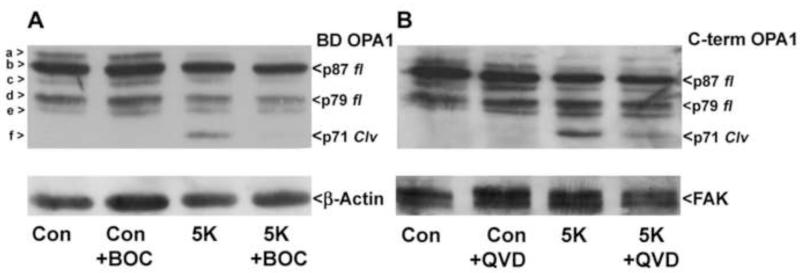

We have previously revealed a novel N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 which is induced by various apoptotic stimuli (Loucks et al., 2009). Specifically, OPA1 cleavage is observed in CGNs upon removal of depolarizing potassium and serum (5K conditions) for 24 hours (Loucks et al., 2009) (Fig. 1A; cleavage product is denoted as band “f”). Consistent with our previous results, this cleavage product is detectable by Western blotting using a monoclonal antibody targeted to an epitope in the middle of the OPA1 sequence (BD OPA1). Next, we examined OPA1 cleavage using a polyclonal antipeptide antibody directed against the last 14 C-terminal residues. The OPA1 cleavage product is also detected with the C-terminal antibody, indicating that the cleavage event occurs at the N-terminus of OPA1 (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, OPA1 cleavage induced under 5K conditions was substantially reduced upon incubation with the broad spectrum caspase inhibitors BOC and QVD (Figs. 1A, B). These results support our previous findings that N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 occurs via a caspase-dependent mechanism during induction of CGN apoptosis via removal of depolarizing potassium.

Fig. 1. Removal of depolarizing extracellular potassium (5K) induces N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 that is caspase-dependent.

(A-B) CGNs were incubated for 24 hours in either control medium (25K + serum) or medium lacking serum and containing only 5mM KCl (5K) +/− broad spectrum caspase inhibitor BOC (10 μM) (A) or QVD (10 μM) (B). OPA1 cleavage (Clv) was detected using a monoclonal antibody that detects residues 708-830 of OPA1 (BD OPA1) (A) or a polyclonal antibody against the C-terminal 14 amino acids, residues 947-960 (C-term) (B). The blots were then stripped and reprobed for β-Actin (A) or FAK (B) as loading controls. OPA1 isoforms a-f are indicated to the left in (A). p87 fl and p79 fl indicate full length OPA1 isoforms. p71 clv denotes the cleavage product.

2.2 Mitochondrial fragmentation occurs in concert with N-terminal cleavage of OPA1

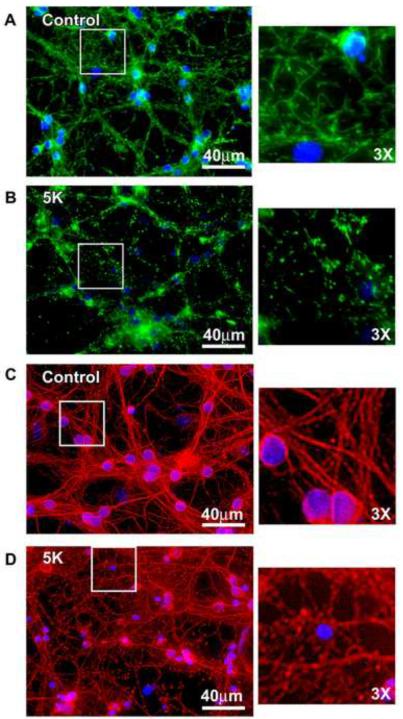

We previously established that the N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 described above removes a key residue, K301, which is critical for the GTPase function of OPA1. This was determined by performing a size comparison of the OPA1 cleavage product with a PCR generated deletion mutant lacking the N-terminal 300 amino acids (Loucks et al., 2009). To further examine the loss of functionality of OPA1 after N-terminal cleavage, we investigated whether 5K treatment elicits increased mitochondrial fragmentation. Mitochondria adopt a rounded and fragmented morphology when CGNs are incubated in 5K for 24 hours, as visualized by MitoTracker Green staining. This is in contrast to the tubular and interconnected mitochondrial morphology that is characteristic of control cells (Figs. 2A, B). To further assess cell morphology during induction of apoptosis, we evaluated fragmentation of the microtubule network, as visualized by β-tubulin immunostaining. CGNs incubated in 5K for 24 hours displayed a slight increase in fragmentation of the microtubule network, demonstrated by the appearance of punctate foci. This is in contrast to the interconnected microtubule network observed in control cells (Figs. 2C, D). However, the microtubule network of 5K-treated cells did not display the degree of fragmentation observed in the mitochondrial networks, indicating that the observed mitochondrial fragmentation was not a result of complete breakdown of cytoskeletal architecture.

Fig. 2. CGNs display significant mitochondrial fragmentation but minimal microtubule disruption following 5K treatment.

(A-B) CGNs were treated as in Fig. 1. Live imaging was performed using MitoTracker to detect mitochondria (green) and Hoechst to detect nuclei (blue). (C-D) CGNs were treated as in (A-B), fixed and immunostained for β-Tubulin (red). Nuclei were detected with DAPI (blue).

2.3 Complex I inhibition with MPP+ induces caspase-independent N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 that is otherwise indistinguishable from that observed during 5K-induced apoptosis

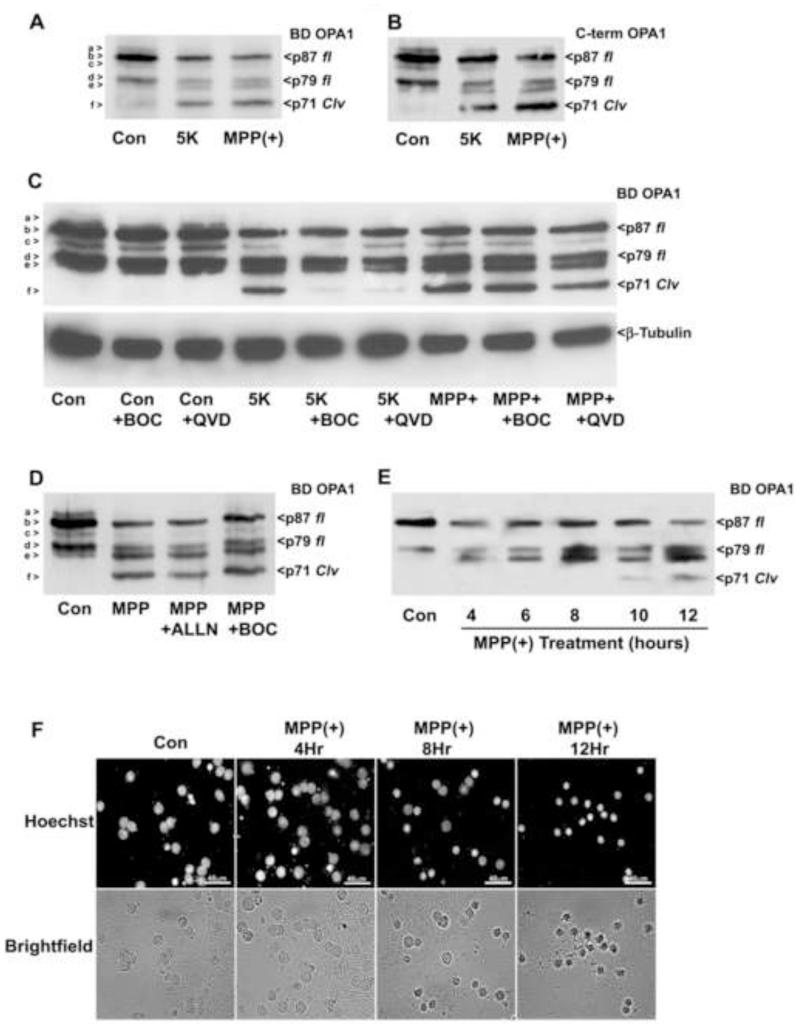

Oxidative stress is implicated as a prominent mechanism of mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal cell death associated with neurodegeneration. We sought to determine the effects of various oxidative stressors on the cleavage of OPA1. Initially, we exposed CGNs to 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), a potent inhibitor of complex I of the electron transport chain often used to model PD. We have previously shown that MPP+ induces CGN death independent of caspase activation (Harbison et al., 2011). Following MPP+ treatment, an OPA1 cleavage product was observed that was indistinguishable from that produced by 5K. The MPP+-induced OPA1 cleavage product was detected by both the BD monoclonal and C-terminal specific OPA1 antibodies (Figs. 3A, B). However, in contrast to the caspase-dependent cleavage of OPA1 induced by 5K treatment, OPA1 cleavage resulting from MPP+ treatment was insensitive to the pan-caspase inhibitors BOC and QVD (Fig. 3C). This indicates that OPA1 cleavage induced by oxidative stress occurs in a caspase-independent manner, via a mechanism distinct from that observed under classically apoptotic conditions (i.e., 5K). Additionally, OPA1 cleavage induced by MPP+ treatment was not inhibited by co-treatment with the calpain inhibitor ALLN (Fig. 3D), indicating that activation of the protease calpain is not a significant factor in the N-terminal cleavage of OPA1. To define a possible role for OPA1 cleavage in oxidative stress-induced CGN death, we compared the timing of OPA1 cleavage to cell death induced by MPP+. OPA1 cleavage was detectable by Western blotting after 10 hours of MPP+ treatment (Fig. 3E). By comparison, nuclear condensation was first apparent after 8 hours of treatment, with significant nuclear condensation occurring after 12 hours of exposure to MPP+ (Fig. 3F). These data indicate that N-terminal OPA1 cleavage likely forms part of the cell death cascade and is not merely an end result of overt cell death induced by MPP+.

Fig. 3. OPA1 cleavage induced by the complex I inhibitor, MPP+, is indistinguishable from 5K-induced OPA1 cleavage but is caspase-independent.

(A-B) CGNs were incubated for 24 hours in either control medium (25K + serum), 5K, or medium containing the complex I inhibitor MPP+ (150 μM). OPA1 cleavage (Clv) was detected by Western blotting using a monoclonal antibody that detects residues 708-830 of OPA1 (BD OPA1) (A) or an antibody that detects the C-terminal 14 amino acids (B). (C) CGNs were incubated in either control medium (25K + serum), 5K, or medium containing 150μM MPP+ as in (A) +/− pan-caspase inhibitors BOC (10 μm) or QVD (10 μm). OPA1 cleavage was detected by Western blotting with a monoclonal antibody to residues 708-830 of OPA1 (BD OPA1). The blot was then stripped and reprobed for β-Tubulin as a loading control. (D) CGNs were treated with MPP+ (150 μM) for 24 hours +/− the calpain inhibitor ALLN or the pan-caspase inhibitor BOC (10 μm). OPA1 cleavage was detected as in (A). (E-F) MPP+ – induced OPA1 cleavage occurs concurrently with nuclear condensation. CGNs were incubated for up to 24 hours in medium containing MPP+ (150 μM), with OPA1 cleavage evaluated by Western blotting as in (A) at 0, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours of treatment. (F) CGNs were incubated in medium containing MPP+ (150 μM) and nuclear morphology was evaluated using either bright-field microscopy or Hoechst stain to detect nuclei at 0, 4, 8 and 12 hours of treatment. OPA1 isoforms a-f are indicated to the left of each Western blot. p87 fl and p79 fl indicate full length OPA1 isoforms. p71 clv denotes the cleavage product.

2.4 MPP+ induces striking mitochondrial fragmentation and complete disruption of the microtubule network in CGNs

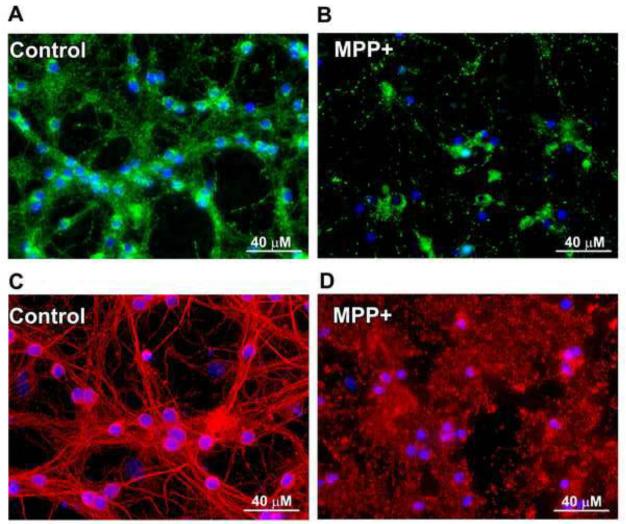

We next investigated whether MPP+ treatment had an effect on mitochondrial fragmentation similar to 5K treatment. MPP+ treatment rendered the mitochondrial network of CGNs completely fragmented, with areas of small punctate foci in addition to areas of larger mitochondrial aggregates. This change in mitochondrial structure was striking in comparison to the interconnected mitochondrial network in control cells (Figs. 4A, B). The effects of MPP+ on the mitochondrial network appeared more severe than those observed with 5K treatment. In addition, the microtubule network was significantly more fragmented with MPP+ than what was observed during 5K treatment, as revealed by very diffuse β-tubulin staining, along with the appearance of tubulin aggregates rather than distinct microtubules as seen in control CGNs (Figs. 4C, D).

Fig. 4. MPP+ induces striking mitochondrial fragmentation and severe microtubule disruption in CGNs.

CGNs were incubated for 24 hours in either control medium (25K + serum) (A, C) or medium containing 150 μM MPP+ (B, D). (A, B) Live imaging was performed using MitoTracker to detect mitochondria (green) and Hoechst to detect nuclei (blue). (C, D) CGNs were treated as in (A, B), fixed and immunostained for β-Tubulin (red). Nuclei were detected with DAPI (blue).

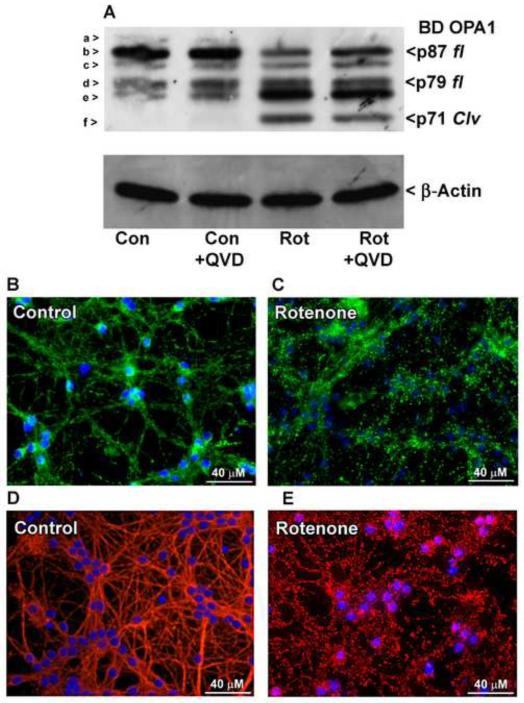

2.5 Rotenone-induced oxidative stress causes caspase-independent OPA1 cleavage, mitochondrial fragmentation, and microtubule disruption

To establish that the results seen with MPP+ treatment are a result of complex I inhibition and not a different aspect of its toxicity, CGNs were exposed to rotenone, another complex I inhibitor. Similar to results of MPP+ treatment, rotenone-treated cells also displayed cleavage of OPA1 to produce the fragment labeled “f”, which was not prevented by co-treatment with the pan-caspase inhibitor QVD (Fig. 5A). These data further support the notion that N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 induced by oxidative stress occurs in a caspase-independent manner. In addition, rotenone treatment rendered the mitochondrial network completely fragmented, demonstrated by scattered areas of small punctate foci detected by MitoTracker staining (Figs. 5B, C). Likewise, the microtubule network also displayed severe fragmentation comparable to that observed with MPP+ treatment (Figs. 5D, E).

Fig. 5. OPA1 cleavage induced by the complex I inhibitor rotenone is caspase-independent and occurs concurrently with mitochondrial and β-tubulin fragmentation.

(A) CGNs were incubated for 24 hours in either control medium (25K + serum) or medium containing electron transport chain complex I inhibitor rotenone (Rot; 10 μM) +/− broad spectrum caspase inhibitor QVD (10 μM). OPA1 cleavage was detected by Western blotting with a monoclonal antibody to residues 708-830 (BD OPA1). The blot was then stripped and reprobed for β-Actin as a loading control. OPA1 isoforms a-f are indicated to the left in (A). p87 fl and p79 fl indicate full length OPA1 isoforms. p71 clv denotes the cleavage product. (B-E) CGNs were incubated for 24 hours in either control medium (25K + serum) or medium containing 10 μM rotenone. (B-C) Live imaging was performed using MitoTracker to detect mitochondria (green) and Hoechst to detect nuclei (blue). (D-E) CGNs were treated as in (B-C), fixed, and immunostained for β-Tubulin (red). Nuclei were detected with DAPI (blue).

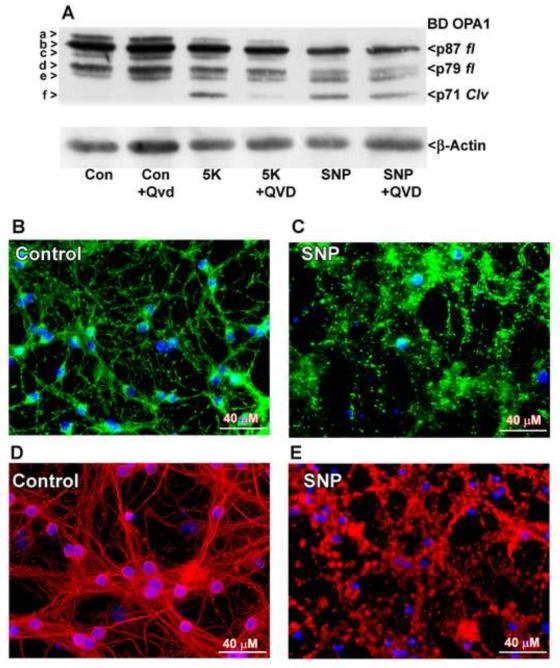

2.6 Reactive nitrogen species (RNS) induces caspase-independent N-terminal cleavage of OPA1, mitochondrial fragmentation, and microtubule disassembly

Due to its high relevance to neurodegeneration, we examined the effects of RNS on OPA1 cleavage. CGNs were exposed to an overnight treatment with sodium nitroprusside (SNP), a nitric oxide donor. As expected, SNP induced N-terminal OPA1 cleavage that was resistant to co-treatment with the pan-caspase inhibitor QVD (Fig. 6A). SNP treatment also caused mitochondria to fragment in a manner similar to treatment with complex I inhibitors (Figs. 6 B, C). In addition, SNP treatment caused disassembly and aggregation of the microtubule network (Figs. 6D, E). Again, this effect was more severe than what was observed with 5K treatment. These results indicate that RNS cause caspase-independent OPA1 cleavage and associated mitochondrial and microtubule fragmentation, similar to what is observed in the presence of ROS generated by inhibition of complex I.

Fig. 6. OPA1 cleavage induced by the nitric oxide donor, SNP, is caspase-independent and occurs concurrently with mitochondrial fragmentation and microtubule disassembly.

(A) CGNs were incubated for 24 hours in either control medium (25K + serum) or medium containing the nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (75 μM) +/− broad spectrum caspase inhibitor QVD (10 μM). OPA1 cleavage was detected by Western blotting using a monoclonal antibody to residues 708-830 (BD OPA1). The blot was then stripped and reprobed for β-Actin as a loading control. OPA1 isoforms a-f are indicated to the left in (A). p87 fl and p79 fl indicate full length OPA1 isoforms. p71 clv denotes the cleavage product. (B-E) CGNs were incubated in either control medium (B, D) or medium containing 200 μM SNP (C, E). (B, C) Live imaging was performed using MitoTracker to detect mitochondria (green) and Hoechst to detect nuclei (blue). (D-E) CGNs were treated as in (B-C), fixed, and immunostained for β-Tubulin (red). Nuclei were detected with DAPI (blue).

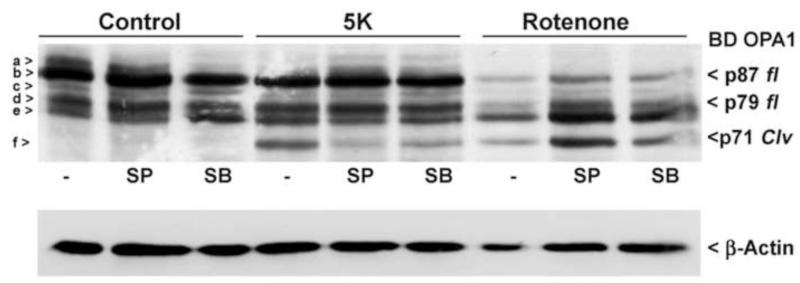

2.7 OPA1 cleavage induced by rotenone is resistant to inhibitors of JNK and p38 MAP kinases

It is well established that the JNK and p38 MAP kinase pathways are major contributors to cell stress responses during oxidative stress-induced apoptosis (Davis, 2000). More specifically, it has been demonstrated that the JNK and p38 MAP kinase pathways are significantly involved in rotenone-induced cell death (Newhouse et al., 2004). For this reason, we sought to examine the effects of inhibiting these pathways under conditions in which N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 occurs. CGNs were exposed overnight to rotenone or 5K treatments, with and without a JNK inhibitor (SP600125) or a p38 MAP kinase inhibitor (SB239063). Interestingly, these inhibitors attenuated 5K-induced OPA1 cleavage, although not to the same extent as the pan-caspase inhibitors BOC and QVD. This effect is likely due to the capacity of JNK and p38 MAP kinase inhibitors to decrease CGN apoptosis in response to 5K treatment and as a result, diminish caspase activity. Surprisingly, rotenone-induced OPA1 cleavage was completely insensitive to JNK and p38 MAP kinase inhibition (Fig. 7). These data further support a distinct pathway for oxidative stress-induced OPA1 cleavage from that of classically apoptotic conditions.

Fig. 7. OPA1 cleavage induced by 5K treatment or rotenone demonstrate differential resistance to inhibition of JNK and p38 MAP kinase.

CGNs were co-incubated for 24 hours in either control medium (25K + serum), 5K medium, or medium containing the complex I inhibitor rotenone (10 μM) +/− the JNK inhibitor II SP600125 (10 μM) or the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB239063 (10 μM). OPA1 cleavage was detected by Western blotting using a monoclonal antibody to residues 708-830 (BD OPA1). The blot was stripped and reprobed for μ-Actin as a loading control. *R.O.D., relative optical density obtained by calculating the ratio of the density of band “f” to actin. OPA1 isoforms a-f are indicated to the left. p87 fl and p79 fl indicate full length OPA1 isoforms. p71 clv denotes the cleavage product.

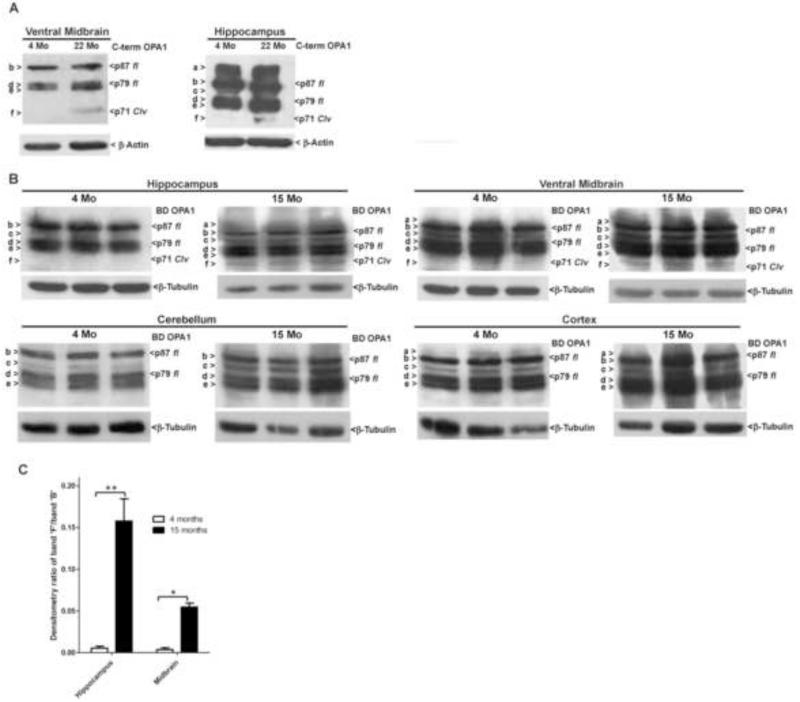

2.8 N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 occurs in aged rat and mouse brain tissues

Increased oxidative damage has been demonstrated to be an attribute of the aging process, particularly in the brain. In the preceding results, we consistently demonstrate OPA1 cleavage in the presence of various oxidative or nitrosative stressors. Therefore, it follows that the increased oxidative stress characteristic of aged brain tissue may similarly lead to OPA1 cleavage. To examine this hypothesis, we obtained midbrain and hippocampal tissue from young (4 month-old) and aged (22 month-old) rats in order to compare processing of endogenous OPA1. Pooled (from 3 rats) midbrain and hippocampal tissues from aged rats displayed an OPA1 cleavage product identical in molecular weight to that observed under oxidative stress and apoptotic conditions in vitro (Fig. 8A). This cleavage product was absent in other aged brain tissues, such as the cerebellum and substantia nigra (data not shown). We next examined endogenous OPA1 cleavage in young (4 month-old) and old (15 month-old) tissues from individual mice. Significant endogenous OPA1 cleavage was observed in hippocampus and midbrain but not cerebellum and cortex. Of note, there was a considerable increase in endogenous OPA1 cleavage observed in aged mouse hippocampal tissue, as compared to other brain tissues examined. (Figs. 8B, C). These results are consistent with increased oxidative stress in aged brain tissue and illustrate that OPA1 cleavage may provide a mechanistic link between mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and neurodegeneration associated with aging.

Fig. 8. OPA1 cleavage is observed in aged midbrain and hippocampual tissues.

(A) Midbrain and hippocampal tissues were obtained from young (4 months) or aged (22 months old) rats, homogenized, and Western-blotted for spontaneous OPA1 cleavage, without exposure to exogenous insults. OPA1 was detected by Western blotting with a polyclonal antibody to the C-terminal 14 amino acids, residues 947-960 (C-term). Blots were then stripped and reprobed for β-Actin as a loading control. (B) Hippocampal, midbrain, cerebellum, and cortical tissues were obtained from young (4 months old) or aged (15 months old) mice, homogenized as in (A), and Western-blotted for spontaneous OPA1 cleavage, without exposure to exogenous insults. OPA1 cleavage was detected by Western blotting using a monoclonal antibody to residues 708-830 (BD OPA1). Blots were then stripped and reprobed for β-Tubulin as a loading control. OPA1 isoforms a-f are indicated to the left. p87 fl and p79 fl indicate full length OPA1 isoforms. p71 clv denotes the cleavage product. (C) Relative optical density of band f observed in young and aged mouse tissue was obtained for each mouse by calculating the ratio of the density of band “f” to band “b”. Results were graphed as mean +/− SEM of each of the three animals for each age and tissue type tested. *= p< 0.05, **=p<0.01, n=3.

3. Discussion

Mitochondrial fission and fusion in mammalian cells is controlled by the dynamin family GTPases Drp1, OPA1, and the mitofusins, Mfn1 and Mfn2. The OPA1 GTPase has two main functions within mitochondria. First, OPA1 works in concert with its binding partner, mitofusin, to promote mitochondrial fusion (Cipolat et al., 2004). Second, long and short forms of OPA1 combine within oligomer complexes that maintain tight cristae junctions (Frezza et al., 2006). OPA1 plays a critical role in each of these functions as demonstrated by the significant mitochondrial fragmentation and disruption of the cristae architecture induced by knockdown of OPA1 expression (Olichon et al., 2003; Griparic et al., 2004). Imbalances in the fission and fusion equilibrium of mitochondria have been linked mechanistically to apoptotic cell death pathways. For instance, the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member, Bax, has been shown to localize to mitochondrial fission sites and, in the case of nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in cortical neurons, requires Drp1 function in order to accumulate in foci along the mitochondrial outer membrane (Karbowski et al., 2002; Yuan et al., 2007). Thus, under some conditions enhanced mitochondrial fission appears to be required upstream of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and cytochrome c release. On the other hand, Bcl-2 homology-3 domain (BH3)-only proteins including Bid and Bnip3, disrupt OPA1 oligomer formation and act in concert with Bax to induce cristae remodeling and promote a maximal release of cytochrome c during induction of apoptosis (Frezza et al., 2006; Yamaguchi et al., 2008; Landes et al., 2010). Collectively, these studies suggest that loss of OPA1 function predisposes cells to apoptosis via two independent pathways including decreased mitochondrial fusion and loosening of cristae junctions. Therefore, unraveling the regulation of OPA1 function is essential to mechanistically define the link between disruption of mitochondrial fission/fusion and induction of apoptosis.

Proper mitochondrial location within the neuron is mediated via microtubule transport. Thus, impairment of this critical network has a direct effect on mitochondrial physiology (Saxton and Hollenbeck, 2012). Our data reveals concomitant fragmentation of the microtubule and mitochondrial networks during oxidative stress. This is in accord with previous literature reporting that peroxynitrite exposure impairs microtubule formation (Landino et al., 2002). More specifically, peroxynitrite and hydrogen peroxide treatments result in cysteine oxidation of microtubule-associated-protein 2 (MAP2) and tau, inhibiting their ability to promote microtubule assembly (Landino et al., 2004). Complex I inhibition by MPP+ and rotenone have been shown to interfere with microtubule assembly through direct binding and destabilizing of tubulin (Capalletti et al., 2005; Marshall and Himes, 1978). Through the establishment that oxidative stress insults have direct effects on the microtubule network, it can be inferred that our observations of microtubule fragmentation are likely from a similar mechanism. The effects of microtubule fragmentation is also linked to perpetuation of the apoptotic cascade, through sequestration of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 homology 3-only (BH3) proteins, such as Bim and Bmf, thereby limiting their ability to bind pro-survival Bcl-2 proteins (Day et al., 2004). This is consistent with reports of apoptotic stimuli disrupting the interaction of the cytoplasmic dynein light chain and the potent pro-death Bim, allowing for inhibition of pro-survival Bcl-2 (Puthalakath et al., 1999). Therefore, it is likely that the microtubule fragmentation observed in our studies results in a similar perpetuation of apoptotic signaling. On the other hand, decreased ATP synthesis resulting from breakdown of mitochondrial function will impair the structure of the tubulin network, thereby propagating microtubule associated apoptotic signaling (Oropesa et al., 2011). Hence, the probability exists that the damage to mitochondria and microtubules observed in our studies has a cyclical property which leads to further breakdown of these critical networks.

OPA1 function is largely regulated through post-translational proteolytic processing within the mitochondria. A relatively large number of mitochondrial proteases including PARL, YME1L1, AFG3L1 -2, Paraplegin, and OMA1, have all been shown to cleave OPA1 under certain conditions (Cipolat et al., 2006; Ishihara et al., 2006; Griparic et al., 2007; Song et al., 2007; Guillery et al., 2008; Ehses et al., 2009). These cleavage events typically result in the processing of long isoforms of OPA1 (denoted “a” and “b” on Western blots) into short isoforms (denoted “c”, “d”, and “e” on Western blots). These long and short isoforms then interact to form functional OPA1 oligomers that promote mitochondrial fusion and cristae architectural integrity (Landes et al., 2010). In fact, a non-cleavable long form of OPA1 is unable to induce mitochondrial fusion when expressed in OPA1 null cells; however, co-expression of short forms of OPA1 restores this fusion capacity (Song et al., 2007). On the other hand, there is also ample evidence that aberrant cleavage of OPA1 which produces an overabundance of short forms disrupts the mitochondrial fusion machinery leading to fragmentation; a situation that occurs during pathological conditions such as loss of mitochondrial membrane potential or induction of apoptosis (Duvezin-Caubet et al., 2006; Ishihara et al., 2006).

Specifically within the context of OPA1 processing during apoptosis, we have previously identified a novel N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 that occurs during apoptotic conditions in primary cultured CGNs and human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. This cleavage event results in the formation of an N-terminal truncated “short” form of OPA1 (denoted “f” on Western blots), that is significantly smaller than a deletion mutant of OPA1 lacking the N-terminal 300 amino acids (Loucks et al., 2009). Thus, this novel short form of OPA1 observed during neuronal apoptosis lacks the critical residue, K301, which is essential for the GTPase function of OPA1 (Griparic and van der Bliek, 2005). Although this cleavage event was determined to be caspase-dependent, caspases failed to directly cleave OPA1 in vitro. In the current study, we reveal an identical OPA1 cleavage event that occurs during oxidative and nitrosative stress-induced cell death in CGNs. The observed OPA1 cleavage product is indistinguishable from that previously observed during classically apoptotic conditions (5K) in CGNs, based on size comparison and recognition with both C-terminal specific antibodies and antibodies specific to the middle portion of OPA1. However, in contrast to our previous findings, co-incubation with the pan-caspase inhibitors, BOC and QVD, failed to inhibit the cleavage of OPA1 induced by oxidative or nitrosative stress conditions in CGNs. This result indicates that OPA1 cleavage occurs in a caspase-independent manner under these conditions, as opposed to the caspase-dependent mechanism observed during 5K-induced CGN apoptosis. Notably, we also demonstrate that this OPA1 cleavage product is present in midbrain and hippocampal tissues obtained from aged mice and rats (15-month-old, 22-month-old, respectively), whereas no OPA1 cleavage product was observed in corresponding tissues taken from young (4-month-old) mice or rats. This finding suggests that OPA1 cleavage may provide a point of convergence between oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging; a mechanistic link that may be particularly relevant to the enhanced risk of neurodegeneration associated with advancing age.

To date, despite testing a large number of protease inhibitors, we have been unable to identify the protease that cleaves OPA1 to generate the novel cleavage product (“f”) described above. Based on our previous and current findings, we postulate that two distinct mechanisms converge to activate the mitochondrial protease responsible for the N-terminal cleavage of OPA1. The first mechanism involves regulation of the unknown OPA1 protease by a caspase. Caspase-mediated activation of proteins is well established in the apoptotic pathway, such as the activation of executioner caspases by initiator caspases or the caspase-8 mediated activation of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein Bid (Li et al., 1998). In addition, caspases have also been shown to remove the regulatory domains of a large number of protein kinases, often resulting in heightened or constitutive activation of the kinase (Lee et al., 1997; Takahashi et al., 1998; Chen et al., 1999; Basu et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2002). Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that in the case of caspase-dependent OPA1 cleavage, activated caspases may directly cleave a negative regulatory domain of the unidentified OPA1 protease resulting in its activation. This is consistent with our observations that caspases are necessary for apoptosis-induced N-terminal cleavage of OPA1, but are incapable of directly cleaving OPA1 in vitro (Loucks et al., 2009). The OPA1 cleavage observed under conditions of oxidative or nitrosative stress apparently involves activation of the unidentified OPA1 protease through a caspase-independent mechanism. One possibility is that this protease could be activated by an oxidative or nitrosative stress-dependent phosphorylation event. However, this seems unlikely since OPA1 cleavage induced by oxidative stress was not significantly affected by inhibitors of JNK or p38 MAP kinases. Another possibility is that the unidentified OPA1 protease is normally sequestered and maintained in an inactive state by its association with the mitochondrial lipid cardiolipin. During conditions of oxidative or nitrosative stress, this protease may then become activated by the oxidation of cardiolipin, perhaps in a manner similar to cardiolipin oxidation allowing for mobilization of cytochrome c (Shidoji et al., 1999). In this context, it is interesting to note that anthocyanins, polyphenolic antioxidants found in fruits and vegetables, significantly inhibit both cardiolipin oxidation and OPA1 cleavage in CGNs exposed to a Bcl-2 inhibitor (Kelsey et al., 2011). Finally, a protease may undergo a direct conformational change as a result of oxidation or nitrosylation, resulting in its activation. Thus, there are numerous possible mechanisms by which a mitochondrial protease might become activated to cleave OPA1 under oxidative or nitrosative stress conditions. Further studies, including identification of the precise cleavage site, are necessary in order to narrow down the search for the mitochondrial protease involved in generating the novel short form (“f”) from OPA1.

The relevance of the present findings to neurodegeneration is supported by the extensive literature demonstrating a significant impact of pathogenic proteins on the mitochondrial fission and fusion machinery in various disease states. For instance, alterations in the expression of multiple fission and fusion proteins have been reported in AD brain, including a significant reduction in OPA1 (Wang et al., 2009). Moreover, oligomeric amyloid-beta-derived diffusible ligands or overproduction of amyloid beta via overexpression of Swedish mutant amyloid precursor protein (APPswe), have each been shown to induce mitochondrial fragmentation in cultured neuronal cells (Wang et al., 2008, 2009). In the case of neuronal cells overexpressing APPswe, simultaneous OPA1 overexpression rescues the mitochondria from fragmentation. In a similar manner, the PD genes, pink1 and parkin, have been shown to negatively regulate OPA1 function and induce mitochondrial fission in Drosophila (Deng et al., 2008). In accordance with these findings, RNAi-induced knockdown of Pink1 in rat hippocampal or midbrain dopaminergic neurons induces hyperfusion of mitochondria, an effect that is suppressed by concurrent knockdown of OPA1 (Yu et al., 2011). Finally, mutant huntingtin protein has recently been shown to bind to Drp1 and enhance its GTPase activity, resulting in significant mitochondrial fragmentation in neurons in vitro and in vivo (Song et al., 2011). Collectively, these studies suggest that aberrant activation or suppression of the mitochondrial fission or fusion machinery likely plays a significant pathogenic role in a number of neurodegenerative disorders. Given these findings, it will be interesting to determine if aberrant processing of OPA1, particularly the generation of the N-terminal truncated cleavage product described here, occurs in disorders such as AD, PD, and Huntington’s disease.

Loss of function of OPA1 has also been linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, mitochondrial oxidative stress, and impaired mitochondrial metabolism. For example, mutations in OPA1 which are causative in dominant optic atrophy cause reductions in ATP synthesis in both fibroblasts and skeletal muscle (Zanna et al., 2008; Lodi et al., 2011). Furthermore, a subset of patients who exhibit mutations in the highly conserved GTPase domain of OPA1 demonstrate multiple phenotypes in addition to progressive blindness, such as deafness, ataxia, and neuropathy. These patients also exhibit increased mutations in mitochondrial DNA, a condition known to be a hallmark of aging (Amati-Bonneau et al., 2008). In accordance with these findings in patients, mice displaying haploinsufficiency of the OPA1 protein demonstrate pathological features of dominant optic atrophy affecting the retinal ganglion cells, but show more subtle neuromuscular and metabolic abnormalities as well (Alavi et al., 2007, 2009). Moreover, these mice also display upregulation of NMDA receptors and enhanced oxidative stress in the retina (Nguyen et al., 2011). This link between OPA1 loss of function and mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress also appears to be significantly associated with aging. For instance, OPA1 expression is lower in skeletal muscle of elderly humans compared to young controls (Joseph et al., 2012). Additional studies suggest that this observation may be more than just correlative since heterozygous mutation of OPA1 in Drosophila or deletion of the OPA1 ortholog, Mgm1p, in the yeast S. cerevisiae, induces a significant shortening of lifespan in each of these model systems (Tang et al., 2009; Scheckhuber et al., 2011). Given the mechanistic link between OPA1 loss of function, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and aging, it is not surprising that we observed OPA1 cleavage in aged rat and mouse midbrain and hippocampal tissues. OPA1 cleavage to generate the novel short form “f” may in fact be a possible biomarker of aging and the declining mitochondrial function associated with this process.

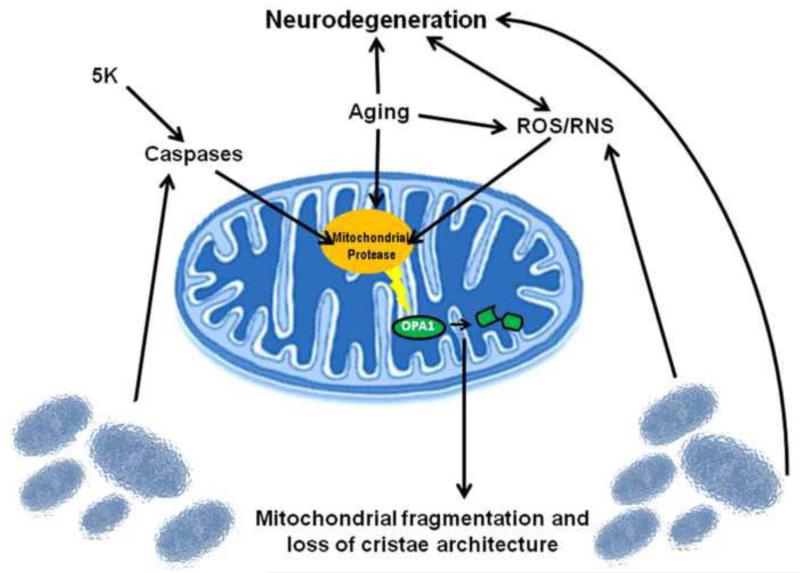

In summary, we propose a model in which an unidentified mitochondrial protease becomes activated as a result of ROS/RNS, increasing age, or through activation of caspases as a result of induction of apoptosis. This mitochondrial protease cleaves the N-terminus of OPA1 removing the key residue K301, and rendering the novel short form of OPA1 (“f”) GTPase deficient. This cleavage event results in a loss of OPA1-dependent fusion, leading to enhanced mitochondrial fission and dismantling of cristae junctions which likely contribute to further mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and induction of apoptosis. We hypothesize that these mechanisms become more pronounced with increasing age as a result of increased ROS/RNS production. Our data suggest that aberrant OPA1 cleavage may be a point of convergence that mechanistically links impairment of the mitochondrial fission/fusion equilibrium with mitochondrial dysfunction, mitochondrial oxidative stress, and neurodegenerative disorders associated with aging (Fig. 9). Future studies aimed at identifying the mitochondrial protease responsible for the OPA1 cleavage event described here may reveal a novel molecular player in aging and neurodegeneration that could be targeted therapeutically to maintain OPA1 function and limit mitochondrial dysfunction in the CNS.

Fig. 9. Schematic of proposed OPA1 cleavage mechanism.

We propose a mechanism in which an unknown protease can become activated through two different pathways. One pathway involves a caspase-dependent activation, as observed under classically apoptotic conditions (5K). A secondary pathway involves activation of the unknown protease in a caspase-independent manner resulting from ROS/RNS stress. Upon activation of the protease, OPA1 becomes cleaved, producing a GTPase-deficient, non-functional C-terminal fragment. Impairment of proper OPA1 GTPase function results in loss of cristae architecture, mitochondrial fragmentation, and ultimately cell death. The ensuing breakdown of mitochondrial function causes further increases in ROS, resulting in continued cleavage of OPA1 and perpetuation of this cell death cascade. Our data demonstrates that OPA1 cleavage occurs spontaneously in aged brain tissue, likely resulting from increased oxidative stress that occurs during the aging process. OPA1 cleavage in aged brain tissue likely contributes to the cell death cascade observed during aging and in neurodegeneration.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1 Reagents

The monoclonal antibody to OPA1 (residues 708-830) was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA). The polyclonal antibody to the C-terminus of OPA1 (residues 947-960) was prepared as described by Zhu et al. (2003). The polyclonal antibody to actin was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies and reagents for enhanced chemiluminescence were from GE Healthcare (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). MitoTracker Green used to detect mitochondria was obtained from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY, USA). The monoclonal β-tubulin antibody, MPP+, the pan-caspase inhibitor BOC-D (OMe)-FMK and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). A CY3-conjugated secondary antibody for immunofluorescence was from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA). Rotenone, sodium nitroprusside (SNP), JNK inhibitor II SP600125, p38MAP kinase inhibitor SB 239063, QVD, and ALLN were from CalBiochem (San Diego, CA, USA).

4.2 Cell Culture

Primary rat cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) were prepared as described previously (Loucks et al., 2009). Briefly, CGNs were isolated from 7-day-old Sprague-Dawley rat pups of both sexes, with the addition of cytosine arabinoside (10 μM) after 24 hours in vitro to inhibit non-neuronal cell growth. Experiments were performed after 6-7 days in vitro (DIV).

4.3 Brain Tissue Preparation

Rat midbrain, hippocampal, cerebellum and substantia nigra tissues were dissected from 4 month-old and 22 month-old Sprague-Dawley rats and immediately dounce-homogenized in lysis buffer. Protein lysates were obtained and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) through 7.5% polyacrylamide gels. Resolved proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Amersham) and immunoblotted as described in the results section. Mouse midbrain, hippocampal, cerebellum and cortical tissues were dissected from 4 month-old and 15 month-old female FVB mice. Tissues were homogenized and protein lysates obtained as described for rat tissues.

4.4 Cell Lysis and immunoblotting

After treatment as described in the Results section, cells were washed once in 1 mL ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4). Cells were incubated for 10 min on ice in lysis buffer (150-200 μl per 35-mm well) prepared as described previously (Loucks et al., 2006). The cells were then harvested by scraping and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 6000 g for 2 min. Protein concentration was determined using BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) with final absorbance of samples measured by a microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek PowerWave XS2, Winooski, VT, USA). Whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE through 7.5% polyacrylamide gels. Resolved proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and processed for immunoblot analysis as previously described (Loucks et al., 2006). In general, western blots shown are representative of a minimum of three independent experiments.

4.5 Immunofluorescence/Mitochondrial Staining

After treatment as described in the Results section, cells were fixed for 1 hour at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde followed by permeabilization and blocking in 0.2% Triton X-100 and 5% BSA in 1X PBS (pH 7.4). To obtain microtubule staining, β-tubulin primary antibody was diluted 1:500 in 2% BSA and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. Cells were incubated in the primary antibody for approximately 16 hours (overnight) at 4°C and subsequently washed five times in 1X PBS and placed in CY3-conjugated secondary antibody and DAPI diluted in 2% BSA and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. Cells were then washed five times in 1X PBS followed by addition of anti-quench (5 mg/ml p-phenylenediamine in 1X PBS). To obtain mitochondria staining, CGNs were treated as described in the Results section and subsequently rinsed in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS). Cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C, 10% CO2 in MitoTracker Green dye and Hoechst stain diluted in HBSS followed by a HBSS rinse. Fluorescent images of both β-tubulin and MitoTracker staining were captured using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope equipped with a Cooke Seniscam CCD camera and Slidebook image analysis software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc., Denver, CO, USA). Five images per well were captured and three experiments were completed per treatment.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by a VA Merit Review Grant and a R01NS062766 grant from NINDS to D.A.L. and the Intramural Research Program of the NINDS, NIH to C.B. The authors acknowledge Emily Schroeder, Natalie Kelsey, and Alexandra Loucks for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- AFG3L1

Human AFG3-like protein 1

- ALLN

N-Acetyl-Leu-Leu-Nle-CHO

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- BOC

Boc-D(OMe)-FMK

- CGNs

cerebellar granule neurons

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- JNK

c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase

- Drp1

dynamin-related protein 1

- MAP

mitogen-activated protein

- m-AAA protease

matrix facing ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities

- MFN

mitofusin

- MPP+

1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium

- MPTP

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- OPA1

optic atrophy -1

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PARL

presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protease

- QVD

qVD-fmk

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aijaz S, Erskine L, Jeffery G, Bhattacharya SS, Votruba M. Developmental expression profile of the optic atrophy gene product: OPA1 is not localized exclusively in the mammalian retinal ganglion cell layer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1667–73. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavi MV, Bette S, Schimpf S, Schuettauf F, Schraermeyer U, Wehrl HF, Ruttiger L, Beck SC, Tonagel F, Pichler BJ, Knipper M, Peters T, Laufs J, Wissinger B. A splice site mutation in the murine Opa1 gene features pathology of autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Brain. 2007;130:1029–42. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavi MV, Fuhrmann N, Nguyen HP, Yu-Wai-Man P, Heiduschka P, Chinnery PF, Wissinger B. Subtle neurological and metabolic abnormalities in an Opa1 mouse model of autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Exp Neurol. 2009;220:404–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amati-Bonneau P, Valentino ML, Reynier P, Gallardo ME, Bornstein B, Boissiere A, Campos Y, Rivera H, de la Aleja JG, Carroccia R, Iommarini L, Labauge P, Figarella-Branger D, Marcorelles P, Furby A, Beauvais K, Letournel F, Liguori R, La Morgia C, Montagna P, Liguori M, Zanna C, Rugolo M, Cossarizza A, Wissinger B, Verny C, Schwarzenbacher R, Martin MA, Arenas J, Ayuso C, Garesse R, Lenaers G, Bonneau D, Carelli V. OPA1 mutations induce mitochondrial DNA instability and optic atrophy ‘plus’ phenotypes. Brain. 2008;131:338–51. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amati-Bonneau P, Milea D, Bonneau D, Chevrollier A, Ferre M, Guillet V, Gueguen N, Loiseau D, de Crescenzo MA, Verny C, Procaccio V, Lenaers G, Reynier P. OPA1-associated disorders: phenotypes and pathophysiology. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1855–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber SC, Shaw PJ. Oxidative stress in ALS: key role in motor neuron injury and therapeutic target. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:629–41. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, Lu D, Sun B, Moor AN, Akkaraju GR, Huang J. Proteolytic activation of protein kinase C-epsilon by caspase-mediated processing and transduction of antiapoptotic signals. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41850–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossy-Wetzel E, Barsoum MJ, Godzik A, Schwarzenbacher R, Lipton SA. Mitochondrial fission in apoptosis, neurodegeneration and aging. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:706–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappalletti G, Surrey T, Maci R. The parkinsonism producing neurotoxin MPP+ affects microtubule dynamics by acting as a destabalising factor. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4781–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chomyn A, Chan DC. Disruption of fusion results in mitochondrial heterogeneity and dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26185–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YR, Meyer CF, Ahmed B, Yao Z, Tan TH. Caspase-mediated cleavage and functional changes of hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 (HPK1) Oncogene. 1999;18:7370–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho DH, Nakamura T, Lipton SA. Mitochondrial dynamics in cell death and neurodegeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:3435–47. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0435-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Dal Zilio B, Scorrano L. OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15927–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407043101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolat S, Rudka T, Hartmann D, Costa V, Serneels L, Craessaerts K, Metzger K, Frezza C, Annaert W, D’Adamio L, Derks C, Dejaegere T, Pellegrini L, D’Hooge R, Scorrano L, De Strooper B. Mitochondrial rhomboid PARL regulates cytochrome c release during apoptosis via OPA1-dependent cristae remodeling. Cell. 2006;126:163–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell. 2000;103:239–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day C, Puthalakath H, Skea G, Strasser A, Barsukov I, Lian L, Huang D, Hinds M. Localization of dynein light chains 1 and 2 and their pro-apoptotic ligands. Biochem. J. 2004;377:597–605. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delettre C, Lenaers G, Griffoin JM, Gigarel N, Lorenzo C, Belenguer P, Pelloquin L, Grosgeorge J, Turc-Carel C, Perret E, Astarie-Dequeker C, Lasquellec L, Arnaud B, Ducommun B, Kaplan J, Hamel CP. Nuclear gene OPA1, encoding a mitochondrial dynamin-related protein, is mutated in dominant optic atrophy. Nat Genet. 2000;26:207–10. doi: 10.1038/79936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delettre C, Griffoin JM, Kaplan J, Dollfus H, Lorenz B, Faivre L, Lenaers G, Belenguer P, Hamel CP. Mutation spectrum and splicing variants in the OPA1 gene. Hum Genet. 2001;109:584–91. doi: 10.1007/s00439-001-0633-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H, Dodson MW, Huang H, Guo M. The Parkinson’s disease genes pink1 and parkin promote mitochondrial fission and/or inhibit fusion in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14503–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803998105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detmer SA, Chan DC. Functions and dysfunctions of mitochondrial dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:870–9. doi: 10.1038/nrm2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvezin-Caubet S, Jagasia R, Wagener J, Hofmann S, Trifunovic A, Hansson A, Chomyn A, Bauer MF, Attardi G, Larsson NG, Neupert W, Reichert AS. Proteolytic processing of OPA1 links mitochondrial dysfunction to alterations in mitochondrial morphology. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37972–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehses S, Raschke I, Mancuso G, Bernacchia A, Geimer S, Tondera D, Martinou JC, Westermann B, Rugarli EI, Langer T. Regulation of OPA1 processing and mitochondrial fusion by m-AAA protease isoenzymes and OMA1. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:1023–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frezza C, Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Micaroni M, Beznoussenko GV, Rudka T, Bartoli D, Polishuck RS, Danial NN, De Strooper B, Scorrano L. OPA1 controls apoptotic cristae remodeling independently from mitochondrial fusion. Cell. 2006;126:177–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griparic L, van der Wel NN, Orozco IJ, Peters PJ, van der Bliek AM. Loss of the intermembrane space protein Mgm1/OPA1 induces swelling and localized constrictions along the lengths of mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18792–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400920200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griparic L, van der Bliek AM. Assay and properties of the mitochondrial dynamin related protein Opa1. Methods Enzymol. 2005;404:620–31. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)04054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griparic L, Kanazawa T, van der Bliek AM. Regulation of the mitochondrial dynamin-like protein Opa1 by proteolytic cleavage. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:757–64. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery O, Malka F, Landes T, Guillou E, Blackstone C, Lombes A, Belenguer P, Arnoult D, Rojo M. Metalloprotease-mediated OPA1 processing is modulated by the mitochondrial membrane potential. Biol Cell. 2008;100:315–25. doi: 10.1042/BC20070110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbison RA, Ryan KR, Wilkins HM, Schroeder EK, Loucks FA, Bouchard RJ, Linseman DA. Calpain plays a central role in 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+)-induced neurotoxicity in cerebellar granule neurons. Neurotox Res. 2011;19:374–88. doi: 10.1007/s12640-010-9172-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Wu YM, Hsu CY, Lee WS, Lai MD, Lu TJ, Huang CL, Leu TH, Shih HM, Fang HI, Robinson DR, Kung HJ, Yuan CJ. Caspase activation of mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 3 (Mst3). Nuclear translocation and induction of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34367–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202468200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara N, Fujita Y, Oka T, Mihara K. Regulation of mitochondrial morphology through proteolytic cleavage of OPA1. Embo J. 2006;25:2966–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P. Oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2003;53(Suppl 3):S26–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.10483. discussion S36-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM, Adhihetty PJ, Buford TW, Wohlgemuth SE, Lees HA, Nguyen LM, Aranda JM, Sandesara BD, Pahor M, Manini TM, Marzetti E, Leeuwenburgh C. The impact of aging on mitochondrial function and biogenesis pathways in skeletal muscle of sedentary high- and low-functioning elderly individuals. Aging Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbowski M, Lee YJ, Gaume B, Jeong SY, Frank S, Nechushtan A, Santel A, Fuller M, Smith CL, Youle RJ. Spatial and temporal association of Bax with mitochondrial fission sites, Drp1, and Mfn2 during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:931–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey N, Hulick W, Winter A, Ross E, Linseman D. Neuroprotective effects of anthocyanins on apoptosis induced by mitochondrial oxidative stress. Nutr Neurosci. 2011;14:249–59. doi: 10.1179/1476830511Y.0000000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott AB, Perkins G, Schwarzenbacher R, Bossy-Wetzel E. Mitochondrial fragmentation in neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:505–18. doi: 10.1038/nrn2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes T, Emorine LJ, Courilleau D, Rojo M, Belenguer P, Arnaune-Pelloquin L. The BH3-only Bnip3 binds to the dynamin Opa1 to promote mitochondrial fragmentation and apoptosis by distinct mechanisms. EMBO Rep. 2010a;11:459–65. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes T, Leroy I, Bertholet A, Diot A, Khosrobakhsh F, Daloyau M, Davezac N, Miquel MC, Courilleau D, Guillou E, Olichon A, Lenaers G, Arnaune-Pelloquin L, Emorine LJ, Belenguer P. OPA1 (dys)functions. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010b;21:593–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landino L, Hasan R, McGaw A, Cooley S, Smith A, Masselam K, Kim G. Peroxynitrite Oxidation of Tubulin Sulfhydryls Inhibits Microtubule Polymerization. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2002;398:213–20. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landino L, Skreslet T, Alston J. Cysteine Oxidation of Tau and Microtubule-associated Protein-2 by Peroxynitrite. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35101–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, MacDonald H, Reinhard C, Halenbeck R, Roulston A, Shi T, Williams LT. Activation of hPAK65 by caspase cleavage induces some of the morphological and biochemical changes of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13642–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhu H, Xu CJ, Yuan J. Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 1998;94:491–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–95. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodi R, Tonon C, Valentino ML, Manners D, Testa C, Malucelli E, La Morgia C, Barboni P, Carbonelli M, Schimpf S, Wissinger B, Zeviani M, Baruzzi A, Liguori R, Barbiroli B, Carelli V. Defective mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate production in skeletal muscle from patients with dominant optic atrophy due to OPA1 mutations. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:67–73. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loucks FA, Schroeder EK, Zommer AE, Hilger S, Kelsey NA, Bouchard RJ, Blackstone C, Brewster JL, Linseman DA. Caspases indirectly regulate cleavage of the mitochondrial fusion GTPase OPA1 in neurons undergoing apoptosis. Brain Res. 2009;1250:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L, Himes R. Rotenone inhibition of tubulin self-assembly. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;543:590–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(78)90315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse K, Hsuan SL, Chang SH, Cai B, Wang Y, Xia Z. Rotenone-induced apoptosis is mediated by p38 and JNK MAP kinases in human dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells. Toxicol Sci. 2004;79:137–46. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D, Alavi MV, Kim KY, Kang T, Scott RT, Noh YH, Lindsey JD, Wissinger B, Ellisman MH, Weinreb RN, Perkins GA, Ju WK. A new vicious cycle involving glutamate excitotoxicity, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dynamics. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e240. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olichon A, Baricault L, Gas N, Guillou E, Valette A, Belenguer P, Lenaers G. Loss of OPA1 perturbates the mitochondrial inner membrane structure and integrity, leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7743–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oropesa M, de la Mata M, Maraver J, Cordero M, Cotán D, Rodriguez-Hernández A, Dominguez-Moñino I, de Miguel M, Navas P, Sánchez-Alcázar J. Apoptotic microtubule network organization and maintenance depend on high cellular ATP levels and energized mitochondria. Apoptosis. 2011;16:404–24. doi: 10.1007/s10495-011-0577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow YP, Green DR, Hao Z, Mak TW. Cytochrome c: functions beyond respiration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:532–42. doi: 10.1038/nrm2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry G, Nunomura A, Hirai K, Zhu X, Perez M, Avila J, Castellani RJ, Atwood CS, Aliev G, Sayre LM, Takeda A, Smith MA. Is oxidative damage the fundamental pathogenic mechanism of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases? Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1475–9. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przedborski S, Vila M. The 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model: a tool to explore the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;991:189–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthalakath H, Huang D, O’Reilly L, King S, Strasser A. The Proapoptotic Activity of the Bcl-2 Family Member Bim is Regulated by Interaction with the Dynein Motor Complex. Mol Cell. 1999;3:287–96. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton W, Hollenbeck P. The axonal transport of mitochondria. Journal of Cell Science. 2012;125:2095–2104. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheckhuber CQ, Wanger RA, Mignat CA, Osiewacz HD. Unopposed mitochondrial fission leads to severe lifespan shortening. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3105–10. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.18.17196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer TB, Richardson JR, Testa CM, Seo BB, Panov AV, Yagi T, Matsuno-Yagi A, Miller GW, Greenamyre JT. Mechanism of toxicity of pesticides acting at complex I: relevance to environmental etiologies of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2007;100:1469–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan C, Martin SJ. Mitochondrial fission/fusion dynamics and apoptosis. Mitochondrion. 2010;10:640–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shidoji Y, Hayashi K, Komura S, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Loss of molecular interaction between cytochrome c and cardiolipin due to lipid peroxidation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;264:343–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Richey Harris PL, Sayre LM, Beckman JS, Perry G. Widespread peroxynitrite-mediated damage in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2653–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02653.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Chen J, Petrilli A, Liot G, Klinglmayr E, Zhou Y, Poquiz P, Tjong J, Pouladi MA, Hayden MR, Masliah E, Ellisman M, Rouiller I, Schwarzenbacher R, Bossy B, Perkins G, Bossy-Wetzel E. Mutant huntingtin binds the mitochondrial fission GTPase dynamin-related protein-1 and increases its enzymatic activity. Nat Med. 2011;17:377–82. doi: 10.1038/nm.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z, Chen H, Fiket M, Alexander C, Chan DC. OPA1 processing controls mitochondrial fusion and is regulated by mRNA splicing, membrane potential, and Yme1L. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:749–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Mukai H, Toshimori M, Miyamoto M, Ono Y. Proteolytic activation of PKN by caspase-3 or related protease during apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11566–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S, Le PK, Tse S, Wallace DC, Huang T. Heterozygous mutation of Opa1 in Drosophila shortens lifespan mediated through increased reactive oxygen species production. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Su B, Siedlak SL, Moreira PI, Fujioka H, Wang Y, Casadesus G, Zhu X. Amyloid-beta overproduction causes abnormal mitochondrial dynamics via differential modulation of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19318–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804871105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Su B, Lee HG, Li X, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9090–103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi R, Lartigue L, Perkins G, Scott RT, Dixit A, Kushnareva Y, Kuwana T, Ellisman MH, Newmeyer DD. Opa1-mediated cristae opening is Bax/Bak and BH3 dependent, required for apoptosis, and independent of Bak oligomerization. Mol Cell. 2008;31:557–69. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Sun Y, Guo S, Lu B. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial dynamics and function in mammalian hippocampal and dopaminergic neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3227–40. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H, Gerencser AA, Liot G, Lipton SA, Ellisman M, Perkins GA, Bossy-Wetzel E. Mitochondrial fission is an upstream and required event for bax foci formation in response to nitric oxide in cortical neurons. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:462–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanna C, Ghelli A, Porcelli AM, Karbowski M, Youle RJ, Schimpf S, Wissinger B, Pinti M, Cossarizza A, Vidoni S, Valentino ML, Rugolo M, Carelli V. OPA1 mutations associated with dominant optic atrophy impair oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial fusion. Brain. 2008;131:352–67. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu PP, Patterson A, Lavoie B, Stadler J, Shoeb M, Patel R, Blackstone C. Cellular localization, oligomerization, and membrane association of the hereditary spastic paraplegia 3A (SPG3A) protein atlastin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49063–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]