Abstract

Background

Duplications of the X-linked MECP2 gene are associated with moderate to severe intellectual disability, epilepsy, and neuropsychiatric illness in males, while triplications are associated with a more severe phenotype. Most carrier females show complete skewing of X-inactivation in peripheral blood and an apparent susceptibility to specific personality traits or neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Methods

We describe the clinical phenotype of a pedigree segregating a duplication of MECP2 found on clinical array comparative genomic hybridization. The position, size, and extent of the duplication were delineated in peripheral blood samples from affected individuals using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification and fluorescence in situ hybridization, as well as targeted high-resolution oligonucleotide microarray analysis and long-range PCR. The molecular consequences of the rearrangement were studied in lymphoblast cell lines using quantitative real-time PCR, reverse transcriptase PCR, and western blot analysis.

Results

We observed a partial MECP2 duplication in an adult male with epilepsy and mild neurocognitive impairment who was able to function independently; this phenotype has not previously been reported among males harboring gains in MECP2 copy number. The same duplication was inherited by this individual’s daughter who was also affected with neurocognitive impairment and epilepsy and carried an additional copy-number variant. The duplicated segment involved all four exons of MECP2, but excluded almost the entire 3' untranslated region (UTR), and the genomic rearrangement resulted in a MECP2-TEX28 fusion gene mRNA transcript. Increased expression of MECP2 and the resulting fusion gene were both confirmed; however, western blot analysis of lysates from lymphoblast cells demonstrated increased MeCP2 protein without evidence of a stable fusion gene protein product.

Conclusion

The observations of a mildly affected adult male with a MECP2 duplication and paternal transmission of this duplication are unique among reported cases with a duplication of MECP2. The clinical and molecular findings imply a minimal critical region for the full neurocognitive expression of the MECP2 duplication syndrome, and suggest a role for the 3′ UTR in mitigating the severity of the disease phenotype.

Keywords: Rearrangement, CNV, 3′ UTR, X-linked intellectual disability, Epilepsy

Background

The MECP2 gene maps to chromosome Xq28 and encodes a methyl CpG binding protein that acts as a transcriptional repressor or activator for genes associated with nerve cell function [1]. Duplications of MECP2 have been described as the cause of Lubs syndrome (OMIM #300260), an X-linked recessive disorder in which affected males manifest a variety of moderate to severe neurological and cognitive phenotypes, including hypotonia, delayed or absent speech, intellectual disabilities, epilepsy, late-onset spasticity, as well as feeding difficulties and recurrent respiratory infections [2-7]. Most males have a reduced life-span, with death occurring within the first three decades of life; although older surviving individuals with severe impairment have been reported [8,9].

Most reported MECP2 duplications are inherited from unaffected or mildly affected carrier mothers, with fewer arising de novo; as yet there have been no reported instances of paternal inheritance [4,10,11]. Carrier mothers typically have normal intelligence and demonstrate near 100% inactivation of the duplication-bearing X chromosome in DNA isolated from peripheral blood, but on more detailed testing most also have an apparent susceptibility to specific personality traits or neuropsychiatric concerns such as depression and anxiety [10,12]. Affected females with X:autosome translocations can have a phenotype that is similar to that seen in affected males; more typically, however, they have partially skewed X chromosome inactivation patterns with milder clinical features than affected males that include short stature, intellectual disability, body asymmetry and epilepsy [9,13-15].

Genotype-phenotype correlation studies suggest that the minimal duplicated region required to recapitulate the MECP2 duplication phenotype includes the entire MECP2 coding sequence and the neighboring IRAK1 gene, and that MECP2 is the primary dosage-sensitive gene mediating neurological outcomes [4,11,16,17]. This contention is further supported by a highly penetrant and more severe neurological phenotype observed with triplications of MECP2[12]. The molecular mechanisms modulating MECP2 expression are complex and include a variety of cis-acting regulatory units, micro-mRNAs, and alternate transcripts [18]. The relative contributions and molecular interactions of these regulatory motifs, however, have yet to be fully elucidated, making the functional regulation of MECP2 expression a subject of intense study and interest.

Here we provide extensive molecular characterization of a MECP2 duplication occurring in a mildly affected adult male and subsequently transmitted to his affected daughter. The uniquely small size of the duplication, together with the unusual molecular and clinical attributes of the affected family, provided the opportunity to potentially gain functional insights into the neurocognitive phenotype of MECP2 duplication syndrome.

Results

Neurocognitive abnormalities in a family segregating two copy number variants (CNVs)

Consultand

The consultand was a Caucasian female who presented at age three years and 10 months, after mild early delays in fine and gross motor development, with loss of speech and significant behavioral problems including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and aggression. She also had hyperacusis, sensitivity to textures and poor eye contact. Formal autism evaluation using the Gilliam Autism Rating scales (GARS) was consistent with a diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder not-otherwise-specified (PDD-NOS), and she was noted to also have problems with cognitive processing. She subsequently developed focal onset seizures and was diagnosed with epilepsy. She was proportionately large for her age (height between 75th - 90th percentiles, weight and head circumference at the 97th and 98th percentiles respectively) with mild dysmorphic features (smooth philtrum, double ear crus, over-folded helix, bilateral 5th finger clinodactyly, talus rotation). When seen at age six years, her seizures were medically refractory, and she had a limited vocabulary with difficulties in speech articulation and required help with dressing and undressing.

Father

The 34-year-old father of the consultand related problems with speech and cognition in childhood that necessitated special education and speech therapy. He completed twelve years of school, and recalled being referred to as learning disabled. He was unable to read or to write. Specific developmental milestones were unavailable, but he did not recall a history of developmental delay. He experienced enuresis until age 18 years and epilepsy with generalized tonic-clonic seizures that began in infancy and continued until pre-adolescence. He did not endorse a history of childhood hypotonia, spasticity, ambulation problems, hospitalization, or frequent or recurrent infections. He was otherwise healthy and on no regular medications. He described himself as being moody and depressed, and he responded positively to all questions on a standard Mood Disorder Questionnaire [19]. On exam, his head circumference was normal, and he was non-dysmorphic apart from short palpebral fissures (more than four standard deviations below normal). He had a normal gait. He was conversant and friendly, but his cognitive processing appeared slow. He described living an itinerant lifestyle with intermittent employment as a day worker, and he gave no formal home address. Formal neuropsychiatric testing was declined, and he has not been available for further medical evaluation.

Pertinent family history

The remainder of the pedigree (Figure 1) was significant for a 4-year-old brother of the consultand with somnambulism and other sleep-related complex behaviors, ADHD, and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The consultand’s mother related difficulty maintaining employment as a result of problems with cognitive processing and executive functioning, for which she received special education during high school. The mother was otherwise healthy. In addition, a maternal half brother was diagnosed with sleep problems and ADHD.

Figure 1.

Pedigree of affected family. The pedigree shows segregation of two copy number variants (CNVs) and neurocognitive diagnoses in the family.

Partial duplications of MECP2

Microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH) on DNA isolated from peripheral blood demonstrated two abnormalities in the consultand: a gain on chromosome 4q35.2 encompassing the MTNR1A and FAT1 genes, sized between 194 and 296 kb, which was also present in the mother and both affected male siblings; and a gain on chromosome Xq28 estimated at approximately 115 kb involving the MECP2 gene (Additional file 1). Array CGH of both parents and the consultand’s male half- and full- siblings indicated that the Xq28 gain in the consultand was paternally inherited and not present in either of the siblings (Figure 1). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies confirmed an interstitial duplication of Xq28, and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) confirmed that all four exons of MECP2 were duplicated in both the consultand and her father (Additional file 2). X-inactivation studies (XCI) performed using the consultand’s DNA showed a moderately skewed pattern (83/17) in peripheral blood cells, with preferential inactivation of the paternally-inherited X-chromosome.

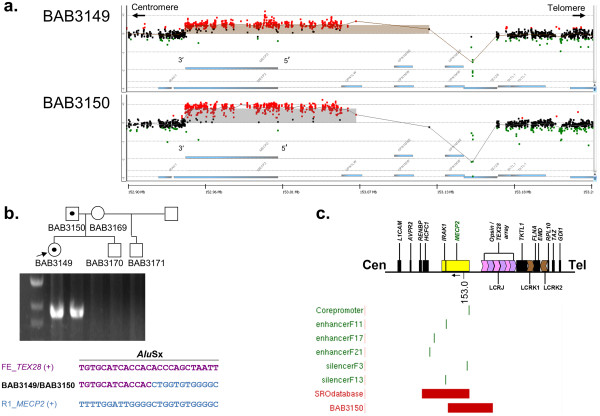

Further analysis using a high-resolution oligonucleotide microarray spanning the MECP2 locus narrowed down the breakpoint junctions to a downstream breakpoint just distal (3′) of the gene and an upstream breakpoint more than 100 kb proximal (5′) of the gene (Figure 2a). A specific breakpoint junction product was obtained by PCR of DNA extracted from peripheral blood and confirmed in DNA from transformed lymphoblast cell lines in those samples that carried the duplication (i.e. consultand and father) (Figure 2b). Sanger dideoxy sequencing of the PCR product revealed no microhomology at the junction, suggesting Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) as the mechanism for formation [11]. The proximal (centromeric) breakpoint mapped within exon 4 of MECP2, sparing almost the entire 3' UTR including three of the four postulated alternative polyadenylation sites [20]. The distal (telomeric) breakpoint mapped to an intron in one of two identical upstream pseudogenes of TEX28, implying that the full size of the duplication was 184.6 or 222.4 kb.

Figure 2.

Molecular characterization of the duplication involving MECP2. a. High-resolution oligonucleotide array CGH results for the consultand (BAB3149) and father (BAB3150) showing a partial duplication of MECP2; b. PCR assay and sequencing result for the breakpoint junction of the duplication flanked by primers 3149R1 + FE. The junctional fragment was observed exclusively in those wells corresponding to consultand (BAB3149) and father (BAB3150); c. Smallest region of overlap (SRO) surmised from a cohort of 30 patients with MECP2 duplication syndrome [11] encompassing HCFC1, IRAK1, MECP2 as well as all known MECP2 cis-regulatory regions (shown in green) [24], compared with the partial duplication observed in the family (illustrated by BAB3150), which does not include the entire pre-defined SRO.

Genomic context of the MECP2 rearrangement

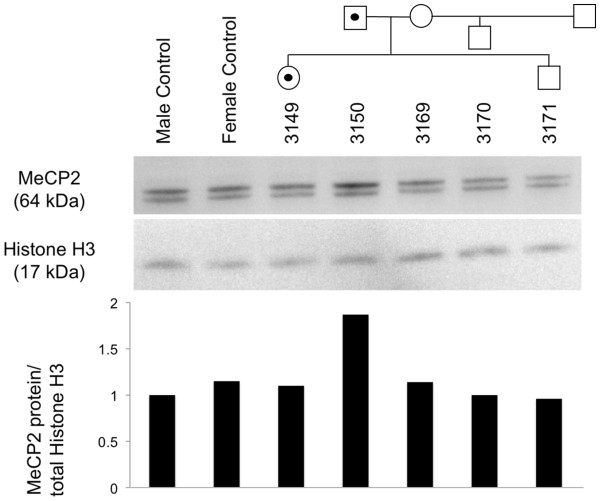

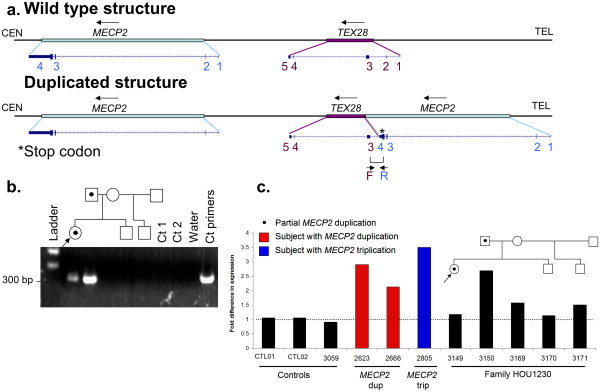

We investigated whether the juxtaposition of the duplicated MECP2 gene adjacent to TEX28 (Figure 3a) produced a fusion gene that might be relevant to the familial phenotypes. PCR was performed using cDNA, with primers designed at the ends of exon three of TEX28 and exon four of MECP2. We identified a genomic rearrangement-associated novel fusion gene in the father and consultand daughter exclusively, using RNA extracted from lymphoblast cell lines. This result was consistent with partial expression of the MECP2 duplicated product in the peripheral blood of the consultand, despite her having moderately skewed X-inactivation. Sequencing of the resulting PCR product (Figure 3b) confirmed the gene fusion.

Figure 3.

Structural depiction and functional assay of partial MECP2 duplication. a. Genomic structure for consultand (BAB3149) and father (BAB3150) surmised using array CGH and breakpoint sequencing analysis. Both wild type (reference) and post-duplication structures are shown for comparison; b. PCR assay and sequencing results for the MECP2-TEX28 fusion gene junction flanked by primers Exon4_R + TEXon2_F3; c. Relative MECP2A mRNA assay for affected family (HOU1230). Control samples: CTL02 and 3059 are males carrying one copy of MECP2; CTL01 is a female carrying one copy of MECP2; 2623 and 2666 are male patients carrying two copies of MECP2 [11]; 2805 is a male patient carrying three copies of MECP2 [12]. Relative fold of mRNA expression changes were calculated using the comparative threshold cycle method (ddCT).

We next sought to determine whether the insertion of a partial copy of MECP2 in a new genomic context would still be associated with increased MECP2 transcription. We used the transcriptional expression of the MECP2A isoform (also known as MECP2-e2 isoform) as a surrogate marker of the normal MECP2 copy, as this isoform is known to be expressed in lymphoblasts [21]. We found that relative to control lymphoblast cell lines, the father demonstrated markedly increased MECP2A transcription, consistent with the levels of transcription typically observed in patients carrying MECP2 duplication and triplication (Figure 3c). This was not observed for any other family members including the consultand. The latter observation may reflect the fact that the clonally obtained lymphoblast cell lines of the female consultand demonstrated more extensive skewing of X-inactivation (96/4, versus 83/17 in peripheral blood) as a consequence of the cloning passage [22]; the lack of appreciable increase in expression in the consultand is therefore considered to be equivocal.

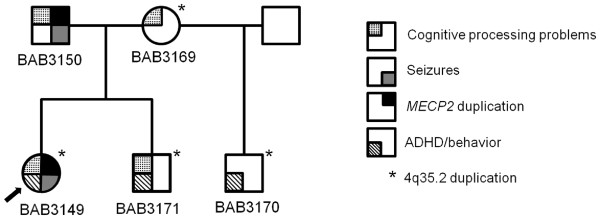

Having observed an apparent increase in MECP2A transcription in the consultand’s father, we then sought to determine whether the increased MECP2 transcription would result in an increase in MeCP2 protein or MeCP2-TEX28 fusion protein. Proteins were extracted from immortalized lymphoblast cell lines of all available family members and a male and female control cell line. MeCP2 protein levels were then quantified and compared to total histone H3 levels used as loading control. Consistent with the results from the transcription experiment, lymphoblasts of the consultand’s father (BA3150) produced 1.9-fold the amount of MeCP2 protein than cells from control individuals, while the other family members (including the consultand (BA3149)) had MeCP2 protein levels similar to normal control individuals (Figure 4). Further, there was no evidence of an additional band in the consultand or her father, which would be expected if a viable fusion protein (MeCP2-TEX28) were formed.

Figure 4.

Comparison of MeCP2 protein levels in pedigree members. MeCP2 protein levels are normalized to histone H3. Individuals 3149 (consultand), 3169 (mother), 3170 (maternal half-brother) and 3171 (brother) have MeCP2 protein levels similar to normal control individuals (female control – CTL01, male control – CTL02); lymphoblasts of individual 3150 (father) produced 1.9-fold the amount of MeCP2 protein observed in cells from control individuals.

Discussion

A MECP2 duplication, partial or complete, occurring in an adult male with minimal symptomatology has not, to the best of our knowledge, been previously reported; neither has paternal transmission of a MECP2 duplication to an affected female offspring. This family is thus both novel and unique among reported patients with MECP2 duplications. In the affected male, the partial duplication is associated with increased MECP2 expression and MeCP2 protein production, and occurs in the context of a clinical presentation that is distinct from the ‘typical’ phenotype of adult males with MECP2 duplication, who usually manifest a greater degree of neurological impairment. The key to this apparent phenotypic conundrum appears to lie with the breakpoints, size, and ultimate physical position of the duplicated segment, all of which are also unique among reported MECP2 duplications.

We previously reported a series of 30 male patients with MECP2 duplications [11], in which the duplication sizes were between 250 kb and 2.6 MB - larger than the 184 or 222 kb size estimated for the consultand’s father. A duplication of similar small size has been reported in an apparently non-dysmorphic female referred for intellectual disability [13], but this duplication was translocated to chromosome 10, and no functional information was reported. The reported smallest region of overlap (SRO) in our series was approximately 140 kb and included both MECP2 and the neighboring IRAK1 gene [4,11]. By comparison, in our present case, the genomic breakpoints are more telomeric (Figure 2c), ostensibly leaving IRAK1 dosage unperturbed. Increased IRAK1 gene dosage has been associated with a history of recurrent infections in some MECP2 duplication patients. This assertion would be consistent with the father’s negative history of recurrent respiratory or other infection; however, given the variable expressivity of the infection phenotype, additional studies are needed to determine whether increased IRAK1 dosage is necessary and/or sufficient to manifest recurrent infections in MECP2 duplication patients.

We speculate that the father’s neurological history, or lack thereof - an affected male with speech delay and epilepsy but without the hypotonia, spasticity, or degree of cognitive and language impairment typically observed in boys with MECP2 duplications – may be the consequence of the specific rearrangement breakpoints within the MECP2 gene. We detected increased expression of the MECP2A mRNA isoforms in his blood and consistently increased MeCP2 protein on western blot. There is evidence from the literature that the MECP2A isoform may not be as biologically relevant in brain as isoform MECP2B[21]. In fact, the ‘long’ MECP2 transcript of 10.2 kb, which is the predominant transcript in the brain, appears to correspond to MECP2B and is present in full only once in this present rearrangement. The duplicated region is predicted to produce only the ‘short’ MECP2 transcript of 1.8 kb, which has higher expression in non-neurological tissues such as heart and muscle [21]. Recent studies using a Cre-LoxP system that specifically disrupts the MECP2A isoform (also known as MECP2-e2) have demonstrated that specific loss of the short transcript does not result in a neurological phenotype in mice [23]. Alternatively (or in addition), it is possible that in the absence of MECP2-associated cis-regulatory elements [24] from the duplicated segment (Figure 2c), the regulation of the duplicated copy in brain may be different from that observed with the wild-type copy. These observations concur with mouse models of Rett syndrome in which disruption of the 3'UTR has been shown to alter MeCP2 protein stability and activity [25,26]. The genomic configuration of the rearrangement together with the clinical picture, lead us to speculate that the overall dosage effect of MECP2 on neuronal activity may be mitigated by effects attributable to the unduplicated 3' UTR segment, resulting in fewer adverse clinical manifestations than are typically seen.

Lastly, although both the consultand and her father share the same duplicated segment, the consultand clearly had a more severe phenotype than her father. It is unusual to find a female with a duplication of MECP2 who is more severely affected than a male family member, since, by definition; females cannot have more skewing than males. Although there exists the possibility of rare cis-acting modifiers of transcription and/or translation a more parsimonious explanation is of a ‘2nd hit’ in which an additional genomic event (structural variant or point mutation) results in a more severe phenotype in the consultand than that expected from the father’s MECP2 duplication [27-29]. The segregation of other neurocognitive phenotypes within the nuclear family gives further credence to this suggestion; the consultand’s mother and two maternal siblings demonstrated a range of neurocognitive and behavioral phenotypes that were similar to the consultand, but none gave a history of seizures. It may be that seizures and some of the neurocognitive defects segregate with the partial MECP2 duplication, whilst autistic features, other additional cognitive defects, and sleep problems are the result of a 2nd hit. As the immediate maternal family members all carried the 4q35 duplication, but not the MECP2 duplication, the 4q35 duplication could represent the 2nd genomic hit in this family. The 4q35 CNV is a small 100 kb region that encodes the melatonin receptor MTNR1A and the transcription factor FAT1. Neither of these genes are known to be dosage-sensitive or disease-causing and a preliminary enquiry of the DECIPHER database (The DECIPHER Consortium, http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk) indicates that larger encompassing duplications have been seen, without a clear clinical phenotype and occasionally inherited from a reportedly normal parent. The segregation of the phenotypes in this family, however, suggests that there may yet be a role for this region in neurocognition and sleep. This is a subject of ongoing study in our laboratory.

Conclusion

Our findings lead us to suggest that the severe neurological and cognitive phenotypes typically observed in the MECP2 duplication syndrome result from duplication of the entire MECP2 coding and cis-regulatory elements. This is consistent with the observation that most, if not all, of the neurological phenotypes observed in the MECP2 duplication syndrome can be recapitulated by duplication of MECP2 alone in mice [16]. Tacitly, our findings imply that copy number gain of the ‘short’, as opposed to the ‘long’, MECP2 transcript and/or disruption of specific 3' regulatory motifs may be associated with an overall milder neurocognitive phenotype, but one that remains susceptible to the development of epilepsy. Given that interpretation of the likely clinical consequences of intragenic duplications can often be challenging without specific breakpoint resolution of the rearrangement [30,31], our findings have potential prognostic implications for genetic counseling of males with intragenic duplications of MECP2. Further studies of the role of the 3′ UTR in modifying the MECP2 duplication phenotype are required to validate the hypotheses generated from this unique family, but, if confirmed, this could become an avenue of fertile and important research going forward.

Methods

Samples

Initial samples from the consultand daughter (BAB3149) were received as a part of her clinical diagnostic evaluation; thereafter, written informed consent was procured for additional research testing on samples from the consultand (BAB3149) as well as the remainder of the nuclear family members (BAB3150 - father, BAB3169 - mother, BAB3170 - maternal-half brother, BAB3171- brother). All studies were performed with the approval of the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Clinical laboratory studies

Chromosomal microarray analysis, GTG-banded (G-bands obtained with trypsin and Giemsa) chromosome analysis, FISH, and MLPA analyses were performed at Baylor College of Medicine Medical Genetics Laboratories (http://www.bcm.edu/geneticlabs/) as described previously [4,32]. X-inactivation studies were based on the protocol described by Allen [32,33] with modifications as described previously [10].

Duplication size and genome content

To determine the size, genomic extent and gene content for each rearrangement, we designed a tiling-path oligonucleotide microarray spanning 4.6 Mb across the MECP2 region on Xq28. The custom 4x44k Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA) microarray was designed using the Agilent e-array website (http://earray.chem.agilent.com/earray/). We selected 22,000 probes covering ChrX: 150,000,000-154,600,000 (NCBI build 36), including the MECP2 gene, which represents an average distribution of 1 probe per 250 bp. Probe labeling and hybridization were performed as described previously [11].

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from immortalized lymphoblast cell lines from all family members, three controls without copy number variation in the Xq28 region (CTL01, female control; CTL02, male control; 3059 male control), two individuals carrying MECP2 duplications (BAB2623 and BAB2666)[11], and one individual carrying a MECP2 triplication (BAB2805)[12]. RNA extraction was carried out on lymphoblasts using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA); this was DNaseI treated and purified using the RNeasy mini kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA using qScript cDNA Super Mix (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD). Quantitative real-time PCR reactions were performed using TaqMan expression assay Hs00172845_m1 from Applied Biosystems (ABI; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) that specifically detects MECP2A transcript. Experiments were carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Four technical replicates were performed for each genomic DNA sample and normalized relative to TBP levels. Reactions were run on the ABI 7900HT fast system. Relative fold of mRNA expression changes were calculated using the comparative threshold cycle method (ddCT).

PCR amplifications

Primers for long-range PCR were designed at the apparent boundaries, as denoted by transitions signifying a gain of the duplicated segment relative to the reference genome as inferred from the custom oligonucleotide microarray result. Long-range PCR was performed using TaKaRa LA Taq (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Primers to obtain the breakpoint junction 3149R1: 5'AGAGAAGATGGATATGACCAGTGGC 3′ and’ FE: 5' GCCTCACCTACACTTCTCCTCCTG 3'. Primer 3149FW1: 5′ TCTACATGTGTGCCTCACT 3′ was used to walk across the 3149R1 + 3149FE PCR product. Detection of the transcript from the fusion gene junction was performed using cDNA from primers: Exon4_R:CCGTGACCGAGAGAGTTAGC and TEXon2_F3:ACTGGCCTTCTCCACTCTCA.

Acid extraction of protein and western blot analysis

Proteins were isolated via acid extraction from confluent cultures of immortalized human lymphoblast cell lines of subjects BA3149, BA3150, BA3169, BA3170, BA3171, a male control individual, and a female control individual. Acid extraction of protein, western blotting, and Immunodetection with anti-MeCP2 antibody 0535, were performed according to our previously published protocol [10]. Immunodetection with antihistone H3 antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA, #06-755, 1:100,000 dilution) was performed as a loading control. MeCP2 and histone H3 protein levels were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and the total MeCP2 protein level was normalized to the level of histone H3 protein detected for each subject.

Competing interests

NH, CC, PF, DP, CS, JRL and SWC are based in the Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine, which offers genetic laboratory testing, including the use of arrays for genomic copy number analysis, and derives revenue from this activity. JRL is a consultant for Athena Diagnostics, has stock ownership in 23andMe and Ion Torrent Systems, and is a co-inventor on multiple United States and European patents for DNA diagnostics. None of the remaining authors have any competing interests to disclose.

Authors’ contribution

nh collated the clinical information, aided in the conceptualization and design of the study, and wrote the manuscript; CC performed the confirmatory experiments, analyzed the data, and assisted in the conceptualization of the paper and the writing of the manuscript; AT assisted in the writing of the manuscript and the conceptualization of the study; PB and LOG evaluated and managed the clinical aspects of the case and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; DdG performed and interpreted the MLPA studies, DP assisted in the performance and analysis of confirmatory experiments; PF oversaw and analyzed the X-inactivation studies; CS performed the western blot analysis and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. MB assisted in the design and conceptualization of the study, was responsible for the cell line establishment, and assisted in the writing of the manuscript; JRL was involved in the conceptualization, execution and analysis of the confirmatory experiments, and helped to draft the manuscript. SWC conceived the study, analyzed and interpreted the cytogenetic studies and array data, and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript for submission.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Clinical arrayCGH of MECP2 and adjacent regions in consultand. Description: The array plot illustrates a gain in copy number (green dots) spanning MECP2 and the adjacent 5′ region in the consultant (BAB3149). Black dots represent normal gene dosage (hybridization intensity) compared to sex-matched controls. Red dots represent oligos with log2 ratios less than −0.3 suggestive of a heterozygous loss.

Clinical laboratory confirmation of MECP2 duplication. Description: a. MLPA of MECP2 in the consultand’s father (BAB3150) demonstrating increased dosage (blue peaks) compared with a normal male control (red peaks). Red asterisks indicate the duplicated MECP2 exons, with MECP2_exon 01 (Start) and MECP2_exon04c (End) probes representing the first and the last duplicated probes in the coding region. Probes located in the proximal L1CAM gene and in the 3′ UTR of the MECP2 gene (MECP2 exon 04b) show normal dosage. b. Fluorescent in-situ Hybridization (FISH) using probes specific for the duplicated region and showing the duplication to be on the X chromosome.

Contributor Information

Neil A Hanchard, Email: hanchard@bcm.edu.

Claudia MB Carvalho, Email: cfonseca@bcm.edu.

Patricia Bader, Email: Patricia.Bader@parkview.com.

Aaron Thome, Email: aaronthome@gmail.com.

Lisa Omo-Griffith, Email: lisa@genesrus.us.

Daniela del Gaudio, Email: ddelgaudio@bsd.uchicago.edu.

Davut Pehlivan, Email: pehlivan@bcm.edu.

Ping Fang, Email: pfang@bcm.edu.

Christian P Schaaf, Email: schaaf@bcm.edu.

Melissa B Ramocki, Email: mramocki@bcm.edu.

James R Lupski, Email: jlupski@bcm.edu.

Sau Wai Cheung, Email: scheung@bcm.edu.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the family for their participation in the study and Dr. Huda Zoghbi for helpful and insightful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) grants R01 NS058529 to J.R.L. and 5K08NS062711-04 to M.B.R. Lymphoblast cell lines were developed by the Baylor College of Medicine Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center cell culture core, which is funded by award P30HD024064 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS or NIH.

References

- Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong ST, Qin J, Zoghbi HY. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science. 2008;320(5880):1224–1229. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meins M, Lehmann J, Gerresheim F, Herchenbach J, Hagedorn M, Hameister K, Epplen JT. Submicroscopic duplication in Xq28 causes increased expression of the MECP2 gene in a boy with severe mental retardation and features of Rett syndrome. J Med Genet. 2005;42(2):e12. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.023804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Esch H, Bauters M, Ignatius J, Jansen M, Raynaud M, Hollanders K, Lugtenberg D, Bienvenu T, Jensen LR, Gecz J. et al. Duplication of the MECP2 region is a frequent cause of severe mental retardation and progressive neurological symptoms in males. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77(3):442–453. doi: 10.1086/444549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Gaudio D, Fang P, Scaglia F, Ward PA, Craigen WJ, Glaze DG, Neul JL, Patel A, Lee JA, Irons M. et al. Increased MECP2 gene copy number as the result of genomic duplication in neurodevelopmentally delayed males. Genet Med. 2006;8(12):784–792. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000250502.28516.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kankirawatana P, Leonard H, Ellaway C, Scurlock J, Mansour A, Makris CM, Dure LS, Friez M, Lane J, Kiraly-Borri C. et al. Early progressive encephalopathy in boys and MECP2 mutations. Neurology. 2006;67(1):164–166. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223318.28938.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyk M, Obersztyn E, Nowakowska B, Nawara M, Cheung SW, Mazurczak T, Stankiewicz P, Bocian E. Different-sized duplications of Xq28, including MECP2, in three males with mental retardation, absent or delayed speech, and recurrent infections. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B(6):799–806. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echenne B, Roubertie A, Lugtenberg D, Kleefstra T, Hamel BC, Van Bokhoven H, Lacombe D, Philippe C, Jonveaux P, de Brouwer AP. Neurologic aspects of MECP2 gene duplication in male patients. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41(3):187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friez MJ, Jones JR, Clarkson K, Lubs H, Abuelo D, Bier JA, Pai S, Simensen R, Williams C, Giampietro PF. et al. Recurrent infections, hypotonia, and mental retardation caused by duplication of MECP2 and adjacent region in Xq28. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):e1687–e1695. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk EP, Malaty-Brevaud V, Martini N, Lacoste C, Levy N, Maclean K, Davies L, Philip N, Badens C. The clinical variability of the MECP2 duplication syndrome: description of two families with duplications excluding L1CAM and FLNA. Clin Genet. 2009;75(3):301–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramocki MB, Peters SU, Tavyev YJ, Zhang F, Carvalho CM, Schaaf CP, Richman R, Fang P, Glaze DG, Lupski JR. et al. Autism and other neuropsychiatric symptoms are prevalent in individuals with MeCP2 duplication syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(6):771–782. doi: 10.1002/ana.21715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho CM, Zhang F, Liu P, Patel A, Sahoo T, Bacino CA, Shaw C, Peacock S, Pursley A, Tavyev YJ. et al. Complex rearrangements in patients with duplications of MECP2 can occur by fork stalling and template switching. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(12):2188–2203. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho CM, Ramocki MB, Pehlivan D, Franco LM, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Fang P, McCall A, Pivnick EK, Hines-Dowell S, Seaver LH. et al. Inverted genomic segments and complex triplication rearrangements are mediated by inverted repeats in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2011;43(11):1074–1081. doi: 10.1038/ng.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makrythanasis P, Moix I, Gimelli S, Fluss J, Aliferis K, Antonarakis SE, Morris MA, Bena F, Bottani A. De novo duplication of MECP2 in a girl with mental retardation and no obvious dysmorphic features. Clin Genet. 2010;78(2):175–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo S, Monfort S, Rosello M, Orellana C, Oltra S, Armstrong J, Catala V, Martinez F. De novo interstitial triplication of MECP2 in a girl with neurodevelopmental disorder and random X chromosome inactivation. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;135(2):93–101. doi: 10.1159/000330917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasshoff U, Bonin M, Goehring I, Ekici A, Dufke A, Cremer K, Wagner N, Rossier E, Jauch A, Walter M. et al. De novo MECP2 duplication in two females with random X-inactivation and moderate mental retardation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(5):507–512. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AL, Levenson JM, Vilaythong AP, Richman R, Armstrong DL, Noebels JL. David Sweatt J, Zoghbi HY: Mild overexpression of MeCP2 causes a progressive neurological disorder in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(21):2679–2689. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugtenberg D, Kleefstra T, Oudakker AR, Nillesen WM, Yntema HG, Tzschach A, Raynaud M, Rating D, Journel H, Chelly J. et al. Structural variation in Xq28: MECP2 duplications in 1% of patients with unexplained XLMR and in 2% of male patients with severe encephalopathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(4):444–453. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, Saxena A, Christodoulou J, Ravine D. MECP2 genomic structure and function: insights from ENCODE. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(19):6035–6047. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, Calabrese JR, Flynn L, Keck PE Jr, Lewis L, McElroy SL, Post RM, Rapport DJ. et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(11):1873–1875. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coy JF, Sedlacek Z, Bachner D, Delius H, Poustka A. A complex pattern of evolutionary conservation and alternative polyadenylation within the long 3'-untranslated region of the methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 gene (MeCP2) suggests a regulatory role in gene expression. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(7):1253–1262. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnatzakanian GN, Lohi H, Munteanu I, Alfred SE, Yamada T, MacLeod PJ, Jones JR, Scherer SW, Schanen NC, Friez MJ. et al. A previously unidentified MECP2 open reading frame defines a new protein isoform relevant to Rett syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36(4):339–341. doi: 10.1038/ng1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plagnol V, Uz E, Wallace C, Stevens H, Clayton D, Ozcelik T, Todd JA. Extreme clonality in lymphoblastoid cell lines with implications for allele specific expression analyses. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e2966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh M, Tahimic CG, Ide S, Otsuki A, Sasaoka T, Noguchi S, Oshimura M, Goto YI, Kurimasa A. Methyl CpG-binding Protein Isoform MeCP2_e2 Is Dispensable for Rett Syndrome Phenotypes but Essential for Embryo Viability and Placenta Development. J Biol Chem. 2012;aa doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.309864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Francke U. Identification of cis-regulatory elements for MECP2 expression. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(11):1769–1782. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaco RC, Fryer JD, Ren J, Fyffe S, Chao HT, Sun Y, Greer JJ, Zoghbi HY, Neul JL. A partial loss of function allele of methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 predicts a human neurodevelopmental syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(12):1718–1727. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr B, Alvarez-Saavedra M, Saez MA, Saona A, Young JI. Defective body-weight regulation, motor control and abnormal social interactions in Mecp2 hypomorphic mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(12):1707–1717. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hattab AW, Zhang F, Maxim R, Christensen KM, Ward JC, Hines-Dowell S, Scaglia F, Lupski JR, Cheung SW. Deletion and duplication of 15q24: molecular mechanisms and potential modification by additional copy number variants. Genet Med. 2010;12(9):573–586. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181eb9b4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girirajan S, Rosenfeld JA, Cooper GM, Antonacci F, Siswara P, Itsara A, Vives L, Walsh T, McCarthy SE, Baker C. et al. A recurrent 16p12.1 microdeletion supports a two-hit model for severe developmental delay. Nat Genet. 2010;42(3):203–209. doi: 10.1038/ng.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupski JR. Structural variation in the human genome. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(11):1169–1171. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr067658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone PM, Bacino CA, Shaw CA, Eng PA, Hixson PM, Pursley AN, Kang SH, Yang Y, Wiszniewska J, Nowakowska BA. et al. Detection of clinically relevant exonic copy-number changes by array CGH. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(12):1326–1342. doi: 10.1002/humu.21360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankiewicz P, Pursley AN, Cheung SW. Challenges in clinical interpretation of microduplications detected by array CGH analysis. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(5):1089–1100. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breman AM, Ramocki MB, Kang SH, Williams M, Freedenberg D, Patel A, Bader PI, Cheung SW. MECP2 duplications in six patients with complex sex chromosome rearrangements. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;19(4):409–415. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RC, Zoghbi HY, Moseley AB, Rosenblatt HM, Belmont JW. Methylation of HpaII and HhaI sites near the polymorphic CAG repeat in the human androgen-receptor gene correlates with X chromosome inactivation. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51(6):1229–1239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Clinical arrayCGH of MECP2 and adjacent regions in consultand. Description: The array plot illustrates a gain in copy number (green dots) spanning MECP2 and the adjacent 5′ region in the consultant (BAB3149). Black dots represent normal gene dosage (hybridization intensity) compared to sex-matched controls. Red dots represent oligos with log2 ratios less than −0.3 suggestive of a heterozygous loss.

Clinical laboratory confirmation of MECP2 duplication. Description: a. MLPA of MECP2 in the consultand’s father (BAB3150) demonstrating increased dosage (blue peaks) compared with a normal male control (red peaks). Red asterisks indicate the duplicated MECP2 exons, with MECP2_exon 01 (Start) and MECP2_exon04c (End) probes representing the first and the last duplicated probes in the coding region. Probes located in the proximal L1CAM gene and in the 3′ UTR of the MECP2 gene (MECP2 exon 04b) show normal dosage. b. Fluorescent in-situ Hybridization (FISH) using probes specific for the duplicated region and showing the duplication to be on the X chromosome.