Abstract

Background

This study forecasts physician supply between 2012 and 2030 using cohort analysis, based on future production capacity and losses from the profession, and assesses if, and by when, the projected numbers of physicians would meet the targets of one doctor per 1,500 population, as proposed by the 7th National Conference on Medical Education in 2001, and one per 1,800, proposed by the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) in 2004.

Methods

We estimated the annual loss rate that best reflected the dynamics of existing practising doctors, then applied this rate to the existing physicians, plus the newly licensed physicians flowing into the pool over the next two decades (from 2012 to 2030). Finally, the remaining practising physicians, after adjustment for losses, were verified against demand projections in order to identify supply gaps.

Results

Thailand has been experiencing an expansion in the total number of physicians, with an annual loss rate of 1%. Considering future plans for admission of medical students, the number of licensed physicians flowing into the pool should reach 2,592 per annum, and 2,661 per annum, by 2019 and 2030 respectively. By applying the 1% loss rate to the existing, and future newly licensed, physicians, there are forecast to be around 40,000 physicians in active clinical service by 2016, and in excess of 60,000 by 2028.

Conclusion

This supply forecast, given various assumptions, would meet the targets outlined above, of one doctor per 1,800 population, and one per 1,500 population, by 2016 and 2020 respectively. However, rapid changes in the contextual environment, e.g. economic demand, physician demographics, and disease burden, may mean that the annual loss rate of 1% used in this projection is not accurate in the future. To ensure population health needs are met, parallel policies on physician production encompassing both qualitative and quantitative aspects should be in place. Improved, up-to-date information and establishment of a physician cohort study are recommended.

Keywords: Cohort analysis, Annual loss rate, Physician projection, Physician to population ratio

Background

The health workforce is one of six key health system components but is often neglected in developing countries [1] when determining success in achieving national health goals, in particular the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [2-4]. A well-functioning health system requires an adequate number of capable, motivated and well-supported health workers; policy makers often ask how many physicians they should produce in order to meet future health needs [5]; accurate predictions of demand for health workers facilitate better production plans.

In the early 1970s, the World Health Organization (WHO) suggested an optimal density of one physician per 5,000 population for developing countries: this ratio was not useful for physician production planning because a country’s level of socio-economic development and the nature of their health-care delivery systems determine the demand for health workers [6]. For instance, in 1992, despite the fact that Thailand had one physician per 4,500 population, well above this benchmark, there were shortages in some areas and maldistribution as a consequence of rapid economic growth that increased demand for doctors in the private health sector in the period from 1992 to 1997 [7-9].

Efforts to forecast demand for, and supply of, health workers, especially physicians, have been ongoing in Thailand since the 1970s [7,10,11]. The summary in Table 1 shows that most studies focused on demand-side projection using service targets or ratios of health workforce per population, with fewer studies applying supply projection.

Table 1.

Studies of demand for and supply of physicians in Thailand from 1972 to 2004

| Year | Organizations | Methodology | Key results and recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before 1972 |

National Economic and Social Development Board |

Physician to population ratio |

Need more physicians to meet the target of one doctor to 5,000 population |

| 1979 |

Coordinating Committee for Medical and Health Affairs |

Service targeted approach |

Thailand needs 200 more doctors per annum to meet the demand for rural health development project. |

| 1986 |

The Thai Medical Council |

Service targeted approach |

Predict a shortage of 4,286 physicians by 2000 |

| 1986 |

National Economic and Social Development Board |

Trend projection |

Adequate supply by the year 2000 |

| 1992 |

Health Planning Division, the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) |

Physician to population ratio |

Increase production in response to increased demand due to economic growth, need 340 more doctors per annum |

| 1994 |

Bureau of Health Policy and Planning, the MoPH |

Combination of physician to population ratio, service targeted and health demand approach |

Increase production to fill in the expanded rural health services. A Collaborative Project to Increase Production of Rural Doctors was decided by the Cabinet to produce 300 more doctors per year |

| 1995-1996 |

Bureau of Health Policy and Planning, Praboromrachanok Institute for Human Resource Development, the MoPH and Health Systems Research Institute |

Combination of physician to population ratio and service targeted and health demand approach |

Adequate supply by 2015 |

| 1996 |

Thailand Development Research Institute |

Health demand approach |

Adequate supply by 2020 |

| 1996 |

Bureau of Policy and Strategy, the MoPH |

Cohort analysis, annual loss rate method and modified physician to population ratio |

The supply of physicians by the year 2020 will be 44,028 (using high-loss scenario) to 47,519 (using low-loss scenario) |

| 2001 |

The 7th National Conference on Medical Education |

Health demand approach and physician to population ratio |

Increase production to reach an optimal ratio of one physician to 1,500 population by 2021 |

| 2004 | Bureau of Policy and Strategy, the MoPH | Physician to population ratio | Increase production to reach an optimal ratio of one physician to 1,800 population; 6,000 additional more physicians should be produced in 2006 |

Sources: Tida Suwannakij (1996); Thaksaphol Thammarangsri (2005).

Among the few studies that did examine supply projection, Suwannakij et al., in 1996 [7], applied cohort analysis and the annual loss rate method. A number of assumptions of physician annual loss rate were applied: <2.5% in an expanding state, >2.5% in a shrinking state and 2.5% for equilibrium state [12]. The 2.5% figure was estimated from the assumption that a physician’s loss from clinical practice would be 100% after 40 years of working, thus the annual loss rate would be 100/40 = 2.5%. The projection appears to have been fairly accurate in projecting the actual number of physicians in the first few years following the study, however, no subsequent studies applied this method and verified whether the forecast of supply matched the demand for physicians as proposed by numerous organizations, as is presented in Table 1 above [13,14].

To fill the gap, this study forecasts physician supply between 2012 and 2030 based on future production capacity and losses from the profession, and assesses whether, and if so when, the projected supplies will meet the respective goals of one doctor per 1,500 population as proposed by the 7th National Conference on Medical Education in 2001, and one per 1,800 population as proposed by the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) in 2004.

Material and method

Among the three types of projection tools available (cohort, observed change and two life-table methods) [15], this study applies the cohort method. Health workforce loss rate is commonly applied in supply projection, especially in cohort and life-table approaches.

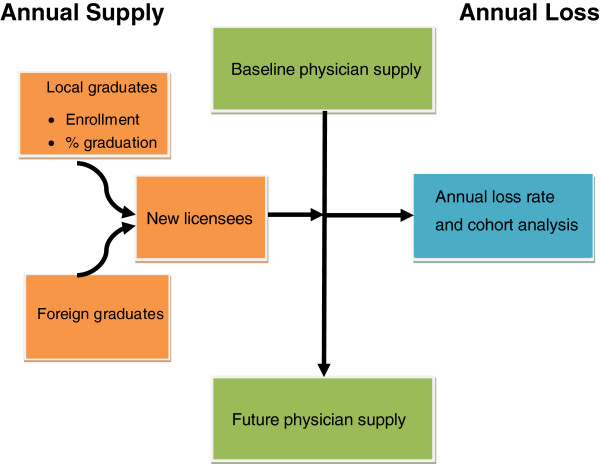

The following approaches were utilised: we estimated the value of an annual loss rate that best reflected the dynamics of existing practising doctors and this loss rate was applied to all existing physicians in the pool, as well as newly licensed physicians flowing into the pool over the next two decades (from 2012 to 2030). Finally, the supply projection of practising physicians adjusted for losses was verified against the demand projection using one per 1,500, and 1,800 population, in order to identify supply gaps See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Framework of the dynamics of physician supply.

In making these projections, we required (a) accurate numbers of the existing pool of practising doctors (stock), (b) the annual number of licensed physicians entering into the pool, both domestic and foreign graduates (flow), minus (c) losses from the profession through death, retirement and leaving clinical practice to take up alternative roles e.g. administration, or research, or leaving the profession entirely. Projections of the supply of practising physicians are reliable when these data are available and accurate [15].

This study applied the assumptions presented in Suwannakij [7] but with new data. Age-specific loss rates was solicited from the opinions of three experts, these were two senior officers within the MoPH and the director of the Health Systems Research Institute [7]. At the time of writing they posited that, in an expanding state, the annual loss rate among 25- to 59-year-olds would be 0.15% to 0.6% (averaging 0.45%) with this annual loss rate, at the end of 35 working years (assuming entry to the workforce at 24 years old), one year before the mandatory retirement age of 60 years old, there would be 81–95% of physicians still pursuing a medical career. At the retirement age of 60 years old, the experts forecasted an annual loss rate of 40%, while during the first 4 years after reaching 60 years old the annual loss rate would decrease to 10%. This would then rebound to 30% annual loss for the remainder of the working period after 64 years old. This meant that only 44% of physicians between 61 and 70 years old would still be engaged in clinical practice, and very few would remain in clinical services after 70 years old.

Flow of future licensed physicians

The number of domestic and foreign graduates gaining a licence to practise was retrieved from the Thai Medical Council. There are 18 public medical schools, and one private medical school, in Thailand. All domestic medical graduates have to pass the comprehensive examination, held by their respective schools, and must also pass the National Licensing Examination, held by the Thai Medical Council, in order to be licensed to practise in Thailand.

Likewise, all foreign medical graduates are required to hold a diploma from a medical school recognized by the Thai Medical Council and must hold a licence to practise in that country [16] prior to applying to sit the National Licensing Examination held by the Council. On passing that exam they can then gain a licence to practice in Thailand.

Graduates who pass the licensing examination

The numbers of local graduates gaining licences was estimated from the rate of graduates who passed the National Licensing Examination multiplied with the number of planned future admissions at all 19 medical schools. Currently, there are no explicit plans from the MoPH or, known private institutes, to open new medical schools in the near future. The number of medical schools used in this study is thus 19.

The historical numbers of medical student admissions were retrieved from the Human Resources for Health Research and Development Office (HRDO), at the MoPH, while the numbers of newly licensed doctors were retrieved from the Thai Medical Council. For newly established medical schools where students have not yet graduated, the average graduation and licensing rate of all other medical schools were applied. The data on the future admission plans of each medical school were retrieved from the HRDO.

This study assumes no significant changes in the number of licensed foreign graduates in the next two decades. The average number of licensed doctors, graduating from overseas, is applied at the same rate for the future as was seen in the past two decades.

Stock of existing physicians and annual loss rate

Stock data on existing licensed doctors between 1937 and 2010 was retrieved from the Thai Medical Council. This dataset counts the registration number, which is unique to each physician, ensuring no double counting. However, this dataset counts all registered physicians regardless of whether they are in active professional service or not, and physicians who have died are not de-registered. We devised methods to clean this dataset with the aim of estimating the number of physicians in active clinical practice.

The Medical Council conducted two surveys of physicians in 2010 and 2011. The surveys reported 37,396 and 39,269 physicians, subdivided by age profile, who were able to be contacted by mail, but unfortunately no information on their current professional practice: see Table 2. We modified this information, the only source that is available, by assuming that all contactable physicians aged 20 to 60 years old, and 44% of physicians 60 to 70 years old, were active in professional life either in clinical service, research, teaching or administration. However, all physicians more than 70 years old were considered inactive. We then calculated the proportion of active physicians to total registered numbers as 83% in 2010 and 2011.

Table 2.

The number of physicians categorized by age group and proportion of active physicians to total registered physicians between 2010 and 2011

| Number of physicians | 2010 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| a) Age 20-30 |

9,865 |

10,234 |

| b) Age 31-40 |

10,553 |

11,292 |

| c) Age 41-50 |

7,386 |

7,620 |

| d) Age 51-60 |

4,959 |

5,202 |

| e) Age 61-70 |

2,347 |

2,543 |

| f) Age more than 70 |

2,178 |

2,280 |

| g) Unknown age |

108 |

98 |

| Total contactable physicians |

37,396 |

39,269 |

| Estimated total active physiciansa |

33,937 |

35,620 |

| Total registered physicians at the Council |

41,015 |

42,890 |

| Proportion of active physicians to total registered physicians | 83% | 83% |

aTotal active physicians = a + b + c + d + (e x 44/100).

Source: The Thai Medical Council (2011).

The calculated figure of 83% was used to reduce the total number of registered physicians, in the years 2000 to 2011, to leave the number of active professionals. Further, a study by Thammarangsri in 2005 showed around 8% of total active physicians did not engage in clinical practice [10]; this figure was applied to scale down the number of active physicians to only those who were actively engaging in clinical services, see the final column of Table 3.

Table 3.

Total registered physicians, estimated active and clinical practising physicians between 2000 and 2011

| Year | Total registered numbers | Total active physicians (83% of registered number) | Total physicians in clinical practice (92% total active physiciansa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 |

26,226 |

21,768 |

19,972 |

| 2001 |

27,498 |

22,823 |

20,940 |

| 2002 |

28,824 |

23,924 |

21,950 |

| 2003 |

30,300 |

25,149 |

23,074 |

| 2004 |

31,730 |

26,336 |

24,163 |

| 2005 |

33,280 |

27,622 |

25,344 |

| 2006 |

34,820 |

28,901 |

26,516 |

| 2007 |

36,392 |

30,205 |

27,713 |

| 2008 |

37,841 |

31,408 |

28,817 |

| 2009 |

39,204 |

32,539 |

29,855 |

| 2010 |

41,015 |

34,042 |

31,234 |

| 2011 | 42,890 | 35,599 | 32,662 |

aAdjusted from Thaksaphol Thammarangsri (2005).

Fine-tuning the annual loss rate

In the last decade, an increasing loss of physicians from the profession has been observed [10,17,18]; the assumed annual loss rate of 0.45% appears to be too low and should, therefore, be re-estimated. The annual loss rate required adjustment to achieve the best fit with the number of active physicians as produced in the final column of Table 3. By gradually increasing the annual loss rate, starting from 0.45%, we found that a 1% annual loss rate best fitted the number of active physicians in the final column of Table 3.

In Figure 2 when a 0.45% annual loss rate was applied, there was a 7% overestimate of the total number of active physicians. However, when a 1% annual loss rate was applied, it closely matched the estimated number of active physicians, see Figure 2. Therefore, we decided to apply a 1% annual loss rate in the projection between 2012 and 2030.

Figure 2.

Comparing estimated active physicians with the results from a 0.45% and a 1% annual loss rate.

Results

Flow of future licensed physicians

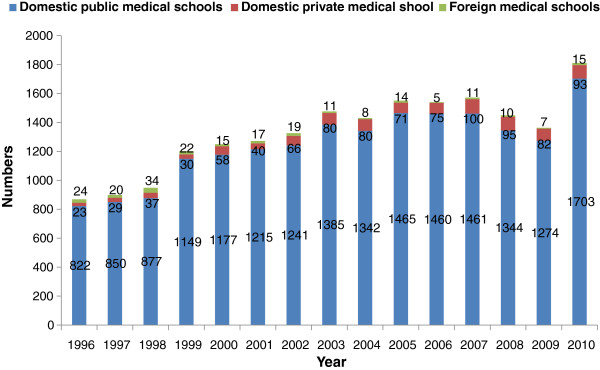

Figure 3 clearly demonstrates the dominant contribution of domestic public medical schools. In 2010, there were approximately 1,800 graduates gaining licences in public schools: double the number in 1996. This was a result of a rapid expansion in the number of public medical schools, from 13 to 18 over the past 15 years. Also, the one existing private medical school tripled their production capacity, from 30 graduates per year in 1999, to 93 graduates in 2010. Licensed physicians from foreign institutions played a negligible role, averaging 15 per annum. There was a dip in the number of licensed doctors from 2007 to 2009 as a result of a reduction in admissions in the 2002 and 2003 student cohorts in response to budget reductions; this rebounded from 2004 onwards as a Cabinet Resolution endorsed the increased production of doctors [19], see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Medical graduates gaining licences from public and private domestic and foreign medical schools between 1996 and 2010.

Table 4 provides the pass rates of medical graduates taking the national licensing examination in 19 schools: ranging from 90.6% in PMK to 99.4% in VJ. The rate from individual schools was applied to Table 5 to estimate the total number of medical graduates gaining licences between 2012 and 2030. With this future admission plan, the flow of future licensed physicians into the pool would exceed 2,500 per year from 2017 onwards See Table 5.

Table 4.

Rates of graduates who passed the National Licensing Examination for each medical school in Thailand

| Medical school | Years of admission | Total admissions | Total graduates who passed the National Licensing Exam | Years of graduation | Rates of graduates who passed the National Licensing Exam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vajira (VJ) |

2001-2004 |

161 |

160 |

2007-2010 |

99.4 |

| Khon Kaen (KK) |

2001-2004 |

599 |

589 |

2007-2010 |

98.3 |

| Chiang Mai (CMU) |

2001-2004 |

664 |

655 |

2007-2010 |

98.6 |

| Thammasat (TU) |

2001-2004 |

348 |

330 |

2007-2010 |

94.8 |

| Princess of Naradhiwas (PNU) |

2007-2011 |

88 |

- |

2013-2017 |

- |

| Naresuan (NSU) |

2003-2004 |

292 |

279 |

2009-2010 |

95.5 |

| Burapha (BU) |

2007-2010 |

144 |

- |

2013-2016 |

- |

| Chulalongkorn (CU) |

2001-2004 |

869 |

846 |

2007-2010 |

97.4 |

| Phayao (PU) |

2011 |

15 |

- |

2017 |

- |

| Phramongkutklao (PMK) |

2001-2004 |

192 |

174 |

2007-2010 |

90.6 |

| Mahasarakham (MSU) |

2007-2010 |

249 |

- |

2013-2016 |

- |

| Ramathibodi (RA) |

2000-2004 |

505 |

494 |

2006-2010 |

97.8 |

| Walailak (WA) |

2008-2010 |

143 |

- |

2014-2016 |

- |

| Srinakharinwirot (SWU) |

2000-2003 |

390 |

376 |

2006-2009 |

96.4 |

| Siriraj (SI) |

2000-2003 |

798 |

791 |

2006-2009 |

99.1 |

| Prince of Songkla (PSU) |

2001-2003 |

583 |

553 |

2007-2009 |

94.9 |

| Suranaree University of Technology (SUT) |

2006-2010 |

240 |

- |

2012-2016 |

- |

| Ubonratchathani (UBU) |

2006-2010 |

134 |

- |

2012-2016 |

- |

| Rangsit (RSU)a |

2000-2004 |

456 |

445 |

2006-2010 |

97.6 |

| Total | 5,857 | 5,692 | 97.2 | ||

aFaculty of Medicine, Rangsit University, is the only private medical school in Thailand.

Source: Human Resources for Health Research and Development Office (HRDO), MoPH (2011).

Table 5.

Future admission plans and projected annual graduates by 19 domestic medical schools and annual foreign graduates

| Medical school | Graduation percentage | Graduates per year | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VJ |

99.4% |

Admissions |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

||

| KK |

98.3% |

Admissions |

247 |

285 |

281 |

275 |

283 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

288 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

243 |

280 |

276 |

270 |

278 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

283 |

||

| CMU |

98.6% |

Admissions |

188 |

188 |

232 |

251 |

249 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

250 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

185 |

185 |

229 |

248 |

246 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

247 |

||

| TU |

94.8% |

Admissions |

134 |

131 |

156 |

161 |

187 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

127 |

124 |

148 |

153 |

177 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

168 |

||

| PNU |

97.2% |

Admissions |

0 |

0 |

16 |

24 |

24 |

24 |

24 |

24 |

24 |

36 |

36 |

36 |

36 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

0 |

0 |

16 |

23 |

23 |

23 |

23 |

23 |

23 |

35 |

35 |

35 |

35 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

||

| NSU |

95.5% |

Admissions |

168 |

128 |

151 |

136 |

172 |

169 |

165 |

165 |

165 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

161 |

122 |

144 |

130 |

164 |

161 |

158 |

158 |

158 |

172 |

172 |

172 |

172 |

172 |

172 |

172 |

172 |

172 |

172 |

||

| BU |

97.2% |

Admissions |

0 |

0 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

0 |

0 |

31 |

31 |

31 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

||

| CU |

97.4% |

Admissions |

248 |

278 |

273 |

291 |

302 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

313 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

241 |

271 |

266 |

283 |

294 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

305 |

||

| PU |

97.2% |

Admissions |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

||

| PMK |

90.6% |

Admissions |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

91 |

||

| MSU |

97.2% |

Admissions |

0 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

0 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

||

| RA |

97.8% |

Admissions |

128 |

131 |

158 |

160 |

161 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

125 |

128 |

155 |

157 |

157 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

||

| WU |

97.2% |

Admissions |

0 |

0 |

0 |

48 |

47 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

0 |

0 |

0 |

47 |

46 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

58 |

58 |

58 |

58 |

58 |

58 |

||

| SWU |

96.4% |

Admissions |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

150 |

165 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

180 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

116 |

116 |

116 |

116 |

116 |

145 |

159 |

174 |

174 |

174 |

174 |

174 |

174 |

174 |

174 |

174 |

174 |

174 |

174 |

||

| SI |

99.1% |

Admissions |

242 |

232 |

233 |

247 |

291 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

292 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

240 |

230 |

231 |

245 |

288 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

289 |

||

| PSU |

94.9% |

Admissions |

175 |

185 |

188 |

183 |

195 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

166 |

175 |

178 |

174 |

185 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

||

| SUT |

97.2% |

Admissions |

0 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

49 |

48 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

0 |

47 |

47 |

47 |

48 |

47 |

58 |

58 |

58 |

78 |

78 |

78 |

78 |

78 |

78 |

78 |

78 |

78 |

78 |

||

| UBU |

97.2% |

Admissions |

0 |

50 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

0 |

49 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

||

| RSU |

97.6% |

Admissions |

100 |

108 |

113 |

137 |

129 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

| Graduates gaining licence |

98 |

105 |

110 |

134 |

126 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

117 |

||

| Total number of graduates gaining licences |

1872 |

2050 |

2179 |

2288 |

2412 |

2511 |

2548 |

2577 |

2577 |

2623 |

2623 |

2623 |

2623 |

2646 |

2646 |

2646 |

2646 |

2646 |

2646 |

||

| Average number of foreign-trained graduates gaining licences |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

||

| Total number of graduates gaining licences | 1887 | 2065 | 2194 | 2303 | 2427 | 2526 | 2563 | 2592 | 2592 | 2638 | 2638 | 2638 | 2638 | 2661 | 2661 | 2661 | 2661 | 2661 | 2661 | ||

Source: The Medical Council of Thailand (2011); Human Resources for Health Research and Development Office (HRDO), MoPH (2011).

Cohort analysis applying the 1% annual loss rate

Additional file 1: Table S1 provides the full cohort analysis table with the application of the 1% annual loss rate for the existing pool and the new licensed doctors flowing into the pool; See Additional file 1: Table S1. The future supply of physicians, active in clinical practice, would be around 40,000 by 2016 and would exceed 50,000 and 60,000 by 2022 and 2028 respectively.

Table 6 compares the future supply of physicians from the cohort analysis with the estimated population in the corresponding period [20]. With these figures, the doctor density would reach the goals of one doctor per 1,800 population and one per 1,500 population by 2016 and 2020 respectively See Table 6.

Table 6.

Projecting physician supply and future population between 2012 and 2030

| Year | Estimated population (thousands)a | Estimated physician supply | Physician to population ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 |

68,251 |

33,471 |

1: 2,039 |

| 2013 |

68,610 |

34,944 |

1: 1,963 |

| 2014 |

68,980 |

36,515 |

1: 1,889 |

| 2015 |

69,222 |

38,168 |

1: 1,814 |

|

2016 |

69,455 |

39,909 |

1: 1,740 |

| 2017 |

69,679 |

41,718 |

1: 1,670 |

| 2018 |

69,893 |

43,540 |

1: 1,605 |

| 2019 |

70,100 |

45,349 |

1: 1,546 |

|

2020 |

70,217 |

47,081 |

1: 1,491 |

| 2021 |

70,330 |

48,762 |

1: 1,442 |

| 2022 |

70,440 |

50,505 |

1: 1,395 |

| 2023 |

70,547 |

52,197 |

1: 1,352 |

| 2024 |

70,651 |

53,864 |

1: 1,312 |

| 2025 |

72,065 |

55,505 |

1: 1,298 |

| 2026 |

72,400 |

57,101 |

1: 1,268 |

| 2027 |

72,734 |

58,666 |

1: 1,240 |

| 2028 |

73,069 |

60,204 |

1: 1,214 |

| 2029 |

73,403 |

61,717 |

1: 1,189 |

| 2030 | 73,738 | 63,212 | 1: 1,167 |

aThe rows highlighted indicate years when the national goals of physician to population ratio of 1:1,800 and 1:1,500 will be achieved.

Source: National Economic and Social Development Board (2003).

Discussion

This study is an extensive attempt at applying the cohort approach in projecting future supply of physicians in Thailand with a 1% annual loss rate. This assumes that the physician population is in an expanding state despite the increase in the annual loss rate in comparison to that found in the previous study by Suwannakij et al. in 1996. Given that the assumptions are valid, especially the 1% annual loss rate, the fine-tuning of the Medical Council dataset on the stock of physicians, the future production capacities of medical schools, and the rate of graduates gaining licences, the projected supplies will be able to match the national goals of one doctor per 1,500 population as proposed by the 7th National Conference on Medical Education by 2020, and one per 1,800 proposed by the MoPH by 2016.

A key factor that has kept the supply of physicians in an expanding state has been the rapid increase in physician production over the past two decades. This has been the result of a set of policies aimed at expanding physician supply, e.g. establishing a number of new public medical schools, recruiting a greater number of students into medical schools, in particular those in remote areas, through various modes of admission. The Collaborative Project to Increase Rural Doctors (CPIRD), launched by the MoPH in 1994, is a good example of these policies. It has enrolled around 300 students per annum from rural backgrounds, with a mandate that these students need to serve their hometown upon graduation [21]. The project also plans to increase its production levels to produce 3,807 graduates between 2009 and 2019.

In carrying out this study, several limitations were addressed with a rigorous evidence-based methodology. However, several remaining limitations were identified as follows:

The assumption that the cohort age-specific loss rate will remain unchanged in the future may not hold true [15], because other elements of the contextual environment may change rapidly, such as, labour market dynamics. Since the recovery from the economic crisis in early 2000, the private sector’s demand for physicians has grown significantly and may cause a brain drain of physicians from the public sector [21]. In the context of the upcoming 2015 inauguration of the ASEAN Economic Community [22], the relaxation of medical council requirements on licensing may increase the number of foreign graduates practising in Thailand; meanwhile, licensing relaxation in recipient countries may stimulate outward migration of Thai physicians to practise abroad. Increased job opportunities in other economic sectors may also stimulate losses from professional practice.

A significant change in the demographics of physicians, specifically the great increase in female students enrolling in medical schools, may affect physicians’ career patterns and as such the loss rate will need further examination. The evidence from a survey of new medical graduates in 2011, by the International Health Policy Program, revealed that only 40% of new graduates were male [23]. This is in contrast to the current gender ratio of overall physicians in Thailand in which around two-thirds of physicians are male [24].

The cleaning of the Thai Medical Council’s dataset on the stock of physicians relied on the 2010 and 2011 surveys, which concluded that 83% of total registered physicians were active in clinical practice; the surveys may have had numerous limitations, such as the representativeness of respondents to the overall physician population, and neither took into account the potential for a return to practice after a career break. This inevitably has an effect on the accuracy of this data.

Focusing on the national average obscures the issue of the sub-national distribution of physicians, for which parallel policies should be in place to address imbalances. This study quantifies the future supply of physicians; however, quality, in terms of clinical competency, communication skills, human interaction, social skills and attitudes and capacity to conduct ‘interprofessional teamwork’, is an equally important factor determining productivity and outcomes. This study indicates that, if the given assumptions hold, current production capacity is adequate to meet the national goals of physician density of 1:1,800 by 2016 and 1:1,500 by 2020, but policy makers should not be complacent as a result of these findings. This supply of physicians, if achieved, does not fully ensure that there will be adequate physicians to respond to the health needs of the population. Maldistribution is still a major policy concern; in 2005, physician density was around 1:800 in Bangkok, almost nine times as high as the density in the Northeast where it was 1:7,000. Almost one quarter of the total number of physicians was employed in the private sector [25] and this trend is increasing [17].

It should be noted that the results of this study will yield greater benefits if integrated into the production and employment planning of other health professions e.g. nurses, dentists, pharmacists, and also medical specialities. Elaborating on the findings of the study, by taking into account the production planning of other professions in concordance with the population’s health needs, may be useful for policy implementation in an effective manner.

Evidence-based health workforce policy and planning requires more accurate data on both stock and flow of physicians. While there has previously been ad hoc physician cohort data collection undertaken, there is a need for regular, routine and integrated collection of physician data by cohort, as part of a strengthening of the whole human resources for health information system. This would improve on the routine registration dataset collected by the Medical Council, ensure greater provision of information to the public, and reflect professional employment dynamics, in particular, losses from the profession and from clinical practice. Ad hoc surveys usually suffer from poor response rates and the non-representativeness of respondents. A 20-year Thai nurse cohort study [26], launched in 2010, provides useful information on the life dynamics of Thai nurses, it monitors the loss rate and assesses the duration of the nursing career – one of the vital parameters in health workforce planning. Lessons from the nurse cohort study would be useful for establishing a physician cohort study in Thailand.

Conclusion

Despite data limitations, given various assumptions and data cleaning of stock, with the application of the cohort approach and a 1% loss rate for both stock and flow, while assuming future production by all medical schools adheres to the plan, this paper thoroughly estimates the future supply of physicians in Thailand. It clearly shows that the desired physician density of 1:1,800 and 1:1,500 can be achieved by 2016 and 2020 respectively.

Given these assumptions, the current production capacity in Thailand can meet the goals of physician density by 2020. However, this may not fully ensure an adequate supply of physicians to respond to the health needs of the population, nor equitable distribution across provinces, unless other parallel policies are in place. Further studies on physician dynamics based on improved, up-to-date and accurate health workforce information, and the establishment of a doctor cohort study are recommended.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Design of the study by RS, TW and NT. Data collection and analyses by RS and VT. Manuscript writing by RS, TW, NT and VT. All authors contributed to the revision of the draft and agreed upon the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Full cohort analysis table with 1% annual loss rate.

Contributor Information

Rapeepong Suphanchaimat, Email: rapeepong@ihpp.thaigov.net.

Thunthita Wisaijohn, Email: thunthita@ihpp.thaigov.net.

Noppakun Thammathacharee, Email: noppakun@ihpp.thaigov.net.

Viroj Tangcharoensathien, Email: viroj@ihpp.thaigov.net.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the kind advice from Dr Suwit Wibulpolprasert and Dr Weerasak Putthasri. We also thank Dr Thinakorn Noree, Dr Nonglak Pagaiya, Dr Thaksapol Thammarangsri, Thai Medical Council staff, Ms Kanang Kantamaturapoj and Mr Tanavij Pannoi, and the Asia Pacific Action Alliance on Human Resources for Health (AAAH) secretariat for sharing data for the analysis. The assistance from Mr Alex Dalliston in language correction is highly appreciated.

References

- World Health Organization. The Kampala Declaration and Agenda for Global Action. Global Health Workforce Alliance, Geneva; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2006: working together for health. World Health Organization, Geneva; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Task Force for Health Systems Research, World Health Organization. Report of the Task Force on Health Systems Research. 2005. Online at http://www.who.int/rpc/summit/en/Task_Force_on_Health_Systems_Research.pdf - accessed on 18 February 2012.

- Travis P. et al. Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet. 2004;364:900–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16987-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TL. Why plan human resources for health? Human Resources for Health Development Journal. 1998;2:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chunharas S. Human resources for health planning: a review of the Thai experience. Human Resources for Health Development Journal. 1998;2:98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Suwannakij T, Sirikanokwilai N, Wibulpolprasert S. Supply projection for physicians in Thailand over the next 25 years (1996–2020 AD) Human Resources for Health Development Journal. 1998;2:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Tancharoensathien V, Nittayaramphong S. Private health care out of control? Health Policy Planning. 1994;9:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V, Nittayaramphong S. In: Private health providers in developing countries, serving the public interest? Bennet S, McPake B, Mills A, editor. St. Martin’s Press, New York; 1997. Private-sector involvement in public hospitals: case-studies in Bangkok; pp. 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Thammarangsri T. Policy Recommendation on Geographical of Physician’s Distribution under Universal Coverage Health Insurance. Health Insurance System Research Office, Bangkok; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sirikanokwilai N, Wibulpolprasert S, Pengpaiboon P. Modified population-to-physician ratio method to project future physician requirement in Thailand. Human Resources for Health Development Journal. 1998;3:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wibulpolprasert S. Human resources for health development in the context of health sector reform. The World Bank Flagship Training Program on Health Sector Reform. World Bank, Washington DC; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Resolution on the 7th National Conference on Medical Education, 2001. Bangkok; 9–11 April 2001. Online at http://www.si.mahidol.ac.th/office_d/meded/meded7/meded7n.html#suggestion - accessed on 17 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Noree T. Fact sheet: the situation on physician attrition from hospitals under the Office of the Permanent Secretary. International Health Policy Program, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kolehmainen-Aitken R-L. Human resources planning: issues and methods. Department of Population and International Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- The Medical Council of Thailand. Regulations concerning the practice of medicine for aliens in Thailand. Online at http://www.tmc.or.th/news02.php - accessed on 17 September 2011.

- Noree T. Crisis of physician shortage in Thailand. International Health Policy Program, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ariyasriwattana C. Shortage of physicians in the Ministry of Public Health. Online at http://www.thaihospital.org/board/index.php?topic=1745.0 - accessed on 17 September 2011.

- Royal Thai Government. Cabinet Resolution on increasing the production capacity of physicians. Bangkok; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Economic and Social Development Board. Population Projections for Thailand 2000–2030. Bangkok; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wibulpolprasert S, Pengpaibon P. Integrated strategies to tackle the inequitable distribution of doctors in Thailand: four decades of experience. Human Resources for Health Development Journal. 2003;1:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations. ASEAN Annual Report 2008–2009. ASEAN Secretariat, Jakarta; 2009. Implementing the roadmap for an ASEAN community 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pagaiya N. et al. Attitude and rural job of choices of newly graduated doctors. Journal of Health Systems Research. 2012;6:30–39. [Google Scholar]

- The Medical Council of Thailand. Physician statistics 2011. Online at http://www.tmc.or.th/statistics.php - accessed on 12 August 2012.

- Summary of the HRH situation in AAAH members. The 6th Asia Pacific Action Alliance on Human Resources for Health (AAAH) Annual Conference. Cebu, Philippines; 9–11 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Health. Thai Nurse Cohort Study. Online at http://www.thainursecohort.org/nu/web/index.php - accessed on 25 August 2012.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full cohort analysis table with 1% annual loss rate.