Abstract

Here we describe a versatile cloning vector for conducting genetic experiments in C. trachomatis. We successfully expressed various fluorescent proteins (i.e. GFP, mCherry and CFP) from C. trachomatis regulatory elements (i.e. the promoter and terminator of the incDEFG operon) and showed that the transformed strains produced wild type amounts of infectious particles and recapitulated major features of the C. trachomatis developmental cycle. C. trachomatis strains expressing fluorescent proteins are valuable tools for studying the C. trachomatis developmental cycle. For instance, we show the feasibility of investigating the dynamics of inclusion fusion and interaction with host proteins and organelles by time-lapse video microscopy.

Introduction

Chlamydia species are obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacterial pathogens that infect genital, ocular and pulmonary epithelial surfaces. Chlamydia are characterized by a biphasic developmental cycle that occurs exclusively in the host cell. The bacteria alternate between an infectious form called the elementary body (EB) that is characterized by a condensed nucleoid, and an intracellular replicative form termed the reticulate body (RB). Once internalized, Chlamydia resides in a membrane bound compartment, named the inclusion. Shortly after uptake, an uncharacterized switch occurs leading to the differentiation of EBs into RBs. The RBs then start to replicate until the inclusion occupies a large part of the cytosol of the host cell. Midway through, the developmental cycle becomes asynchronous and RBs start to differentiate back into EBs. At the end of the cycle, which last two to three days depending on the species, EBs are released from the host cell allowing infection of neighboring cells [1], [2].

To establish and maintain their intracellular niche, Chlamydia release effectors proteins into the host cell cytosol. Some target cellular organelles or signaling pathways, while others act directly at the inclusion membrane [3]–[5]. Once internalized [6]–[8], Chlamydia directs the trafficking of the nascent inclusion to a perinuclear localization via a mechanism involving microfilaments, microtubules and the motor protein dynein [9]. The inclusion does not interact with the endocytic pathway [9], [10] and is encased in a scaffold of host actin and intermediate filaments that maintain vacuole integrity [11]. Infection induces Golgi fragmentation and formation of Golgi ministacks that surround the inclusion to favor the interception of exocytic vesicles and lipids, such as cholesterol and sphingomyelin [12], [13]. Membrane contact sites between C. trachomatis inclusion membrane and endoplasmic reticulum patches have also been described [14]. Localization of the ceramide transfer protein, CERT, and the sphingomyelin synthase 2, SMS2, at these points of contact may be involved in sphingomyelin synthesis directly at the inclusion membrane, representing an alternative route for lipids acquisition [14], [15].

Genetic intractability of obligate intracellular pathogens has made it challenging to fully dissect the role of virulence factors involved in pathogenesis. Over the past 10 years, significant advances have occured and elaborated genetic systems have been developed for most obligate intracellular pathogens [16].

To date Coxiella burnetii, the causative agent of Q fever [17], has the most comprehensive set of genetics tools including i) transposons used to generate mCherry expressing Coxiella strains, random transposition mutagenesis [18] and site-specific transposition integration [19], ii) shuttle vectors allowing mutant complementation and ß-lactamase- or CyA-based secretion assay of type IV effectors [19], [20], iii) an anhydrotetracycline-inducible system [19] and iv) two systems for targeted gene deletion [21]. The development of a medium that supports axenic growth of Coxiella [22] has certainly facilitated the development of Coxiella genetic tools, but major advances have also been accomplished for true obligates such as Rickettesiae spp. Allelic exchange of the phospholipase D gene of R. prowazekii has been reported [23], but genetic manipulation of several Rickettesiae species has mostly relied on random transposition generating mCherry and GFP expressing strains [24]–[27], and most importantly in the context of the study of host-pathogen interaction, an insertional inactivation mutant strain that is defective for actin-based motility [28].

Genetic tools to study Chlamydia pathogenesis have also emerged. In 1998, the sequence of the C. trachomatis genome revealed the presence of DNA repair and recombination systems, indicating that C. trachomatis was capable of recombination [29]. Several studies have since provided evidence that lateral gene transfer between C. trachomatis strains, or different Chlamydia species, occurred in vitro and in vivo [30]–[34].

The first observation of C. trachomatis transformation by electroporation leading to transient expression of chloramphenicol resistance was reported in 1994 [35] and in 2009, allelic exchange using circular and linear DNA was reported in C. psittaci [36]. Over the past year major advances have occurred and C. trachomatis is now considered an obligate intracellular pathogen for which genetic manipulation is still challenging but certainly not impossible. A transformation system, based on calcium rather than electroporation, has been developed and E. coli-C. trachomatis shuttle plasmids were successfully introduced and maintained in C. trachomatis leading to C. trachomatis strains that were resistant to ß-lactams and expressed GFP [37]. Transposition mutagenesis is yet to be developed, but chemical mutagenesis has been used to generate targeted C. trachomatis mutant in the tryptophan synthesis pathway [38]. In combination with genome sequencing and a system of DNA exchange among Chlamydia strains, a collection of mutants with distinct phenotypes, including mutants with altered glycogen metabolism and with disrupted type II secretion, were also generated [39].

In an effort to further develop C. trachomatis genetic tools, that could lead to routine mutation and complementation, we have developed a versatile cloning vector for C. trachomatis. We successfully expressed various fluorescent proteins (i.e. GFP, mCherry and CFP) from the C. trachomatis incDEFG operon promoter and showed that the transformed strains produced wild type amounts of infectious particles and recapitulated major features of the C. trachomatis developmental cycle. C. trachomatis strains expressing fluorescent proteins are valuable tools for the study of the C. trachomatis developmental cycle by time lapse video microscopy, but more importantly, our cloning vector will be a valuable tool for mutant complementation as well as expression of wild type, mutated or tagged C. trachomatis proteins to investigate their role during the C. trachomatis developmental cycle.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All genetic manipulations and containment work were approved by the Yale Biological Committed and are in compliance with the section III-D-1-a of the National Institutes of Health guidelines for research involving recombinant DNA molecules.

Cell lines and bacterial strains

HeLa cells cells were obtained from ATCC (CCL-2) and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in DMEM high glucose (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS (Invitrogen). C. trachomatis Lymphogranuloma venereum, Type II were obtained from ATCC (L2/434/Bu VR-902B). Chlamydia propagation and infection was performed as previously described [40].

Plasmid construction

Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). PCR was performed using Herculase DNA polymerase (Stratagene). PCR primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies and their sequence is listed in Table S1. The maps of the plasmids described below were designed using Vector NTI (Invitrogen).

Construction of p2TK2

p2TK2 was amplified from pGEX-2TK (GE Healthcare) with Mod2TK2-5-Nde and Mod2TK2-3-Nde primers. The corresponding PCR product, containing the E. coli origin of replication, the ß-lactamase gene and a multiple cloning site, was circularized after NdeI digest.

Construction of p2TK2-SW2

pSW2 was obtained by BamHI digest of pGFP: SW2 [37] and gel purification of the ∼7 kb band corresponding to pSW2. To construct p2TK-SW2, BamHI digested pSW2 was cloned into the BamHI site of p2TK2.

Construction of p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm

DNA fragments corresponding to the intergenic region upstream (IncD Prom) and downstream (IncD Term) of the incDEFG operon were amplified by PCR from C. trachomatis genomic DNA using primers IncDProm&Orf-5-Kpn and RSGFP-START-3 (IncD Prom) and RSGFP-STOP-5 and IncDTerm-3-Not (IncD Term), respectively. A DNA fragment corresponding to RSGFP was amplified from pGFP: SW2 using primers RSGFP-START-5 and RSGFP-STOP-3. A DNA fragment corresponding to IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm was then amplified by overlapping PCR and cloned into the KpnI/NotI sites of p2TK2. p2TK2--SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm was obtained by cloning the pSW2 plasmid into the BamHI site of p2TK2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm. Please note the opposite orientation of pSW2 in p2TK2--SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm and p2TK2-SW2.

Construction of p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm

DNA fragments corresponding to the intergenic region upstream (IncD Prom) and downstream (IncD Term) of the incDEFG operon were amplified by PCR from C. trachomatis genomic DNA using primers IncDProm&Orf-5-Kpn and mCherry-START-3 (IncD Prom) and mCherry-STOP-5 and IncDTerm-3-Not (IncD Term), respectively. A DNA fragment corresponding to mCherry was amplified using primers mCherry-START-5 and mCherry-STOP-3. A DNA fragment corresponding to IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm was then amplified by overlapping PCR and cloned into the KpnI/NotI sites of p2TK2-SW2.

Construction of p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm

DNA fragments corresponding to the intergenic region upstream (IncD Prom) and downstream (IncD Term) of the incDEFG operon were amplified by PCR from C. trachomatis genomic DNA using primers IncDProm&Orf-5-Kpn and CFP-START-3 (IncD Prom) and CFP-STOP-5 and IncDTerm-3-Not (IncD Term), respectively. A DNA fragment corresponding to CFP was amplified using primers CFP-START-5 and CFP-STOP-3. A DNA fragment corresponding to IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm was then amplified by overlapping PCR and cloned into the KpnI/NotI sites of p2TK2-SW2.

C. trachomatis transformation

The following protocol was adapted from Wang et. al. [37]. HeLa cells and C.trachomatis L2 were obtained from ATCC. The transformed plasmids were extracted from the E. coli GM2163 (dam − dcm −) strain using an endofree plasmid maxi Kit (Qiagen). Infected cells were cultured in DMEM High Glucose supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS (Invitrogen). Penicillin G and Cycloheximide were from Sigma. The optimal penicillin concentration to select the transformants (1 U/ml) was empirically determined by serial dilution. Once established, the transformed strains were cultured in the presence of 10 U/ml of penicillin.

For one transformation:

Day 1. C. trachomatis L2 in 10 µl of SPG, 6 µg of plasmid DNA in 10 µl of water and 200 µl of CaCl2 Buffer (10 mM Tris, 50 mM CaCl2 pH 7.4) were incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature. 4×106 trypsinized HeLa cells were pelleted, washed once with PBS and resuspended in 200 µl of CaCl2 Buffer. After 30 minutes, HeLa cells (200 µl) were added to the C. trachomatis L2/DNA mix and incubated for an additional 20 minutes at room temperature with mixing by pipetting up and down every 5 minutes. At the end of the 20 minutes, 100 µl of C. trachomatis L2/plasmid DNA/HeLa mix was added to a 6 well containing 3 ml of media and incubated for 48 h at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. The amount of C. trachomatis to be used was empirically determined so that 100% of the cells were infected.

Day 2. 4×106 HeLa cells were seeded in a 10 cm2 dish.

Day 3. 100% of the cells (from day 1) were infected and displayed wild type inclusions. The media was removed, the infected cells were lyzed by addition of 2 ml of water, scrapped, collected and spun for 5 minutes at 1,200 rpm. The supernatant was diluted in 10 ml of media containing 1 U/ml penicillin and 1 µg/ml Cycloheximide. The dilution was empirically determine so that when added to the cell monolayer seeded on day 2 and incubated for 48 h at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2, 100% of the cells would be infected.

Day 4. 4×106 HeLa cells were seeded in a 10 cm2 dish.

Day 5. 100% of the cells from day 3 were infected. The inclusions were large but contained aberrant bodies. The media was removed, the infected cells were lyzed (by scrapping the cells in 2 ml of water and passing through a 26 G1/2 needle 5 times), collected and spun for 5 min at 1,200 rpm. The 2 ml of lysate was diluted in 8 ml of media containing 1 U/ml penicillin and 1 µg/ml Cycloheximide, transferred to the monolayer seeded on day 4 and incubated for 3 days at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2.

Day 7. 4×106 HeLa cells were seeded in a 10 cm2 dish.

Day 8. Some wild type inclusions were observed and the amplification process started. The media was removed, the infected cells were lyzed (by scrapping the cells in 2 ml of water and passing through a 26 G1/2 needle 5 times), collected and spun for 5 min at 1,200 rpm. The 2 ml of lysate was diluted in 8 ml of media containing 10 U/ml penicillin and 1 µg/ml Cycloheximide, transferred to the monolayer seeded on day 7 and incubated for 2–3 days at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2.

The amplification process was repeated until enough infectious particles were recovered to generate a frozen stock and proceed to purification.

Plasmid and genomic DNA extraction

Confluent HeLa cells in 10 cm2 dishes were infected with the parental or the transformed strains at an MOI of 1 and the bacteria were harvested 48 h post infection. Plasmid and total (plasmid and genomic) DNA were respectively prepared using a QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen) and an illustra bacteria genomicPrep Mini Spin Kit (GE Healthcare), according the manufacturer recommendations.

Verification of the integrity of the incDEFG locus by PCR

C. trachomatis total (plasmid and genomic) DNA was used a template. The ChrUpIncDProm and ChrDwnIncDTerm primers were used to amplify the incDEFG operon from the chromosome. The DNA fragment corresponding to the rsgfp gene, flanked by the incD promoter and terminator, was amplified using the primers PlasmUpIncDProm and PlasmDwnIncDTerm. The DNA fragments corresponding to the mcherry or cfp gene, flanked by the incD promoter and terminator, were amplified using the primers 2TK2Fwd and SW2Rev2.

Southern Blot

C. trachomatis total (plasmid and genomic) DNA was digested with BamHI, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and transferred to positively charged nylon membrane. Hybridization with digoxigenin-11-dUTP-labeled probes was performed overnight at 50°C and DIG detection was performed according to the manufacturer recommendation (Roche). The 2TK2 probe was a 2,021 bp DNA fragment corresponding to the p2TK2 plasmid and was generated using the primers Mod2TK2-5-Nde and Mod2TK2-3-Nde. The SW2 probe was a 500 bp DNA fragment corresponding to pSW2 plasmid and was generated using the primers SW2ProbeFwd and SW2ProbeRev.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

At the indicated times, the cells seeded onto glass coverslips were fixed for 30 min in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde. Immunostaining was performed at room temperature. Antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 0.1% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100. Samples were washed with PBS and examined under an epifluorescence or spinning disc confocal microscope.

Infectious progeny production

HeLa cells were collected at the indicated time post infection, lyzed with glass beads and dilutions of the lysate were used to infect fresh HeLa cells. The cells were fixed 24 h post infection and the number of inclusion forming units (IFUs) was determined after assessment of the number of infected cells by immonulabelling.

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used: goat polyclonal anti-MOMP (1∶300, Virostat), rabbit polyclonal anti-C. trachomatis IncA (1∶200, kindly provided by T. Hackstadt, Rocky Mountain Laboratories), chicken polyclonal anti-CERT (1∶200, Sigma), mouse monoclonal anti-GM130 (1∶300, BD Biosciences) and mouse monoclonal anti-Vimentin (1∶500, Sigma).

The following secondary antibodies were used: donkey anti-goat AlexaFluor 488 antibody (1∶1,000, Molecular Probes), goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 594 or 488 antibody (1∶1,000, Molecular Probes), FITC or TRICT donkey anti-chicken IgY antibody (1∶500, Jackson ImmunoResearch) and goat anti-mouse AlexaFluor 594 or 488 antibody (1∶1,000, Molecular Probes).

DNA transfection

DNA transfection was performed using Fugene 6 according to the manufacturer recommendations.

Time-lapse video microscopy

HeLa cells were seeded on 35-mm imaging dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) and transfected with the indicated construct 18 hrs prior to infection with the indicated fluorescent C. trachomatis strain. At the indicated times post infection, images were captured every 20–30 min on a Nikon TE2000E spinning disc confocal microscope equipped with a humidified live cell environmental chamber set at 37°C and 5% CO2. The Volocity software (Improvision, Lexington, MA) was used to analyze and process the data. Videos were saved in QuickTime format using Sorenso 3 compression.

Results and Discussion

Generation of a versatile cloning vector for C. trachomatis

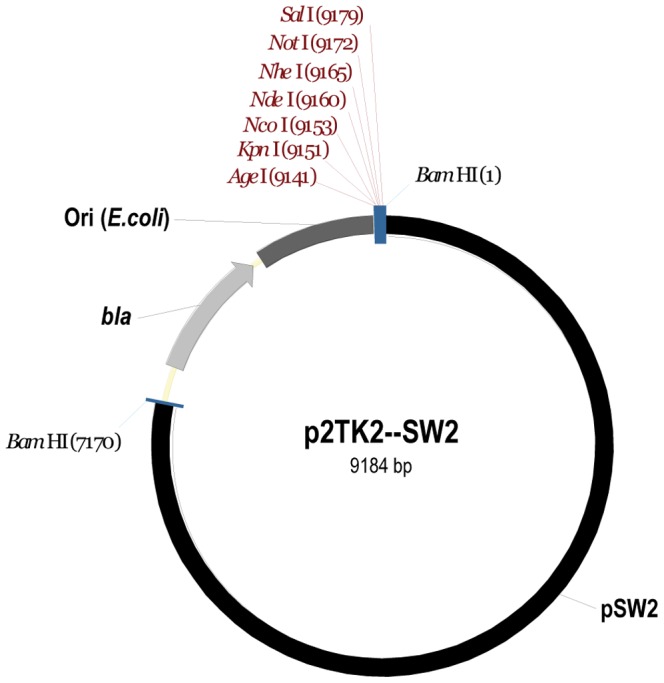

With the objective of developing a versatile cloning vector for C. trachomatis, we first generated p2TK2, a minimal plasmid for replication in E. coli, containing an ampicillin resistance cassette, a pBR322 origin of replication and a multiple cloning site (Figure S1 (map), Figure S2 (sequence) and Materials and Methods). Based on the organization of the plasmids developed by Wang et. al., we then generated the E. coli-C. trachomatis shuttle plasmid, p2TK2-SW2, by introducing the C. trachomatis SW2 plasmid into the BamHI restriction site of p2TK2 (Figure 1 (map), Figure S3 (sequence) and Materials and Methods).

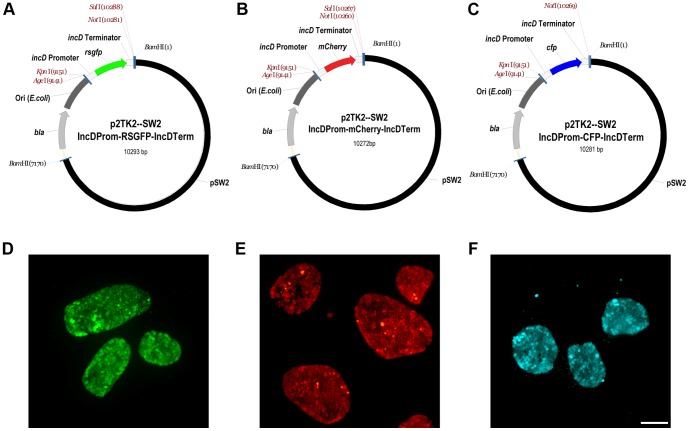

Figure 1. A versatile cloning vector for C. trachomatis.

Map of p2TK-SW2. The pSW2 plasmid is shown in black, the E.coli origin of replication in dark grey and the ampicillin resistance cassette (bla) in light grey. Unique restriction sites of the multiple cloning site are shown in red.

The p2TK2-SW2 cloning vector was then introduced into C. trachomatis by incubating bacteria, DNA and HeLa cells in CaCl2/Tris Buffer as described by Wang et. al. ([37], Materials and Methods). Wild type inclusions were observed after two rounds of penicillin selection. After a third round of selection, the majority of the HeLa cells displayed large wild type inclusions. After clonal isolation of the transformants, we compared the growth characteristics of the parental and transformed strains (Figure 2). HeLa cells were infected with the parental strain, C. trachomatis L2, or the transformed strain harboring p2TK2-SW2 for 24 h in the absence or presence of penicillin. Fixed samples were stained with the DNA dye Hoechst and antibodies against Chlamydia Major Outer Membrane Protein (MOMP) were used to visualize the bacteria. As shown in Figure 2A, in the absence of penicillin the parental strain developed normal inclusion filled with wild type bacteria, whereas large aberrant bacteria were observed in the presence of penicillin. On the contrary, the transformed strain harboring p2TK2SW2, displayed inclusions harboring wild type bacteria both in the absence and in the presence of penicillin, confirming that the p2TK2--SW2 plasmid confers C. trachomatis resistance to penicillin.

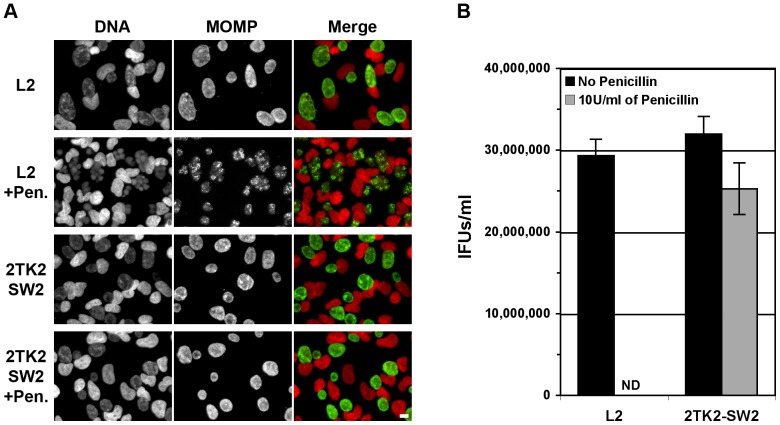

Figure 2. Growth characteristics of C. trachomatis L2 and the transformed strain harboring p2TK2--SW2.

A. HeLa cells were infected with the parental strain, C. trachomatis L2, or the transformed strain harboring p2TK2--SW2 for 24 h in the absence (L2 and 2TK2SW2) or presence of penicillin (L2+Pen and 2TK2SW2+Pen). Fixed samples were stained with the DNA dye Hoechst (DNA, left panels) and antibodies against Chlamydia Major Outer Membrane Protein (MOMP) (MOMP, middle panels) were used to visualize the bacteria. The merge images are shown on the right (Red: DNA, Green: MOMP). Scale bar: 10 µm. B. HeLa cells were infected with the parental strain, C. trachomatis L2, or the transformed strain harboring p2TK2--SW2 in the absence (Black bars, No Penicillin) or in the presence of penicillin (Grey bars, 10 U/ml Penicillin). The number of infectious particles (IFUs) recovered 48 h post infection was determined. ND: None Detected.

We also compared the production of infectious particles of the parental and transformed strain harboring p2TK2--SW2 (Figure 2B). For this purpose, HeLa cells were infected with the parental strain, C. trachomatis L2, or the transformed strain harboring p2TK2-SW2 in the absence or presence of penicillin and the number of infectious particles recovered 48 h post infection was determined. In agreement with the immunofluorescence data, the parental strain was only able to produce infectious progeny in the absence of penicillin (Figure 2B, L2, black bar), whereas the transformed strain harboring p2TK2SW2 produced infectious particle both in the absence and in the presence of penicillin (Figure 2B, 2TK2SW2, black and grey bars). Importantly, equal amounts of progeny were recovered from both strains, indicating that the presence of the plasmid did not affect the production of infectious particles.

Altogether our results indicate that a C. trachomatis transformed strain harboring the p2TK2-SW2 cloning vector displayed resistance to penicillin and produced similar amount of infectious C. trachomatis to the parental strain.

C. trachomatis transformants expressing RSGFP, mCherry or CFP from the incD gene promoter

We next generated versatile vectors allowing for expression of fluorescent proteins under the control of C. trachomatis regulatory elements. We chose the promoter and terminator regions of the incDEFG operon because it belongs to the class of Chlamydia genes that are expressed early and throughout the developmental cycle [41]. By overlapping PCR, we created a KpnI/NotI DNA fragment where the gfp ORF was flanked by the promoter and terminator regions of the incDEFG operon. The E. coli-C. trachomatis shuttle plasmid, p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm, was then generated by ligation of the IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm DNA fragment into the KpnI and NotI restriction sites of p2TK2-SW2 (Figure 3A (map), Figure S4 (sequence) and Materials and Methods).

Figure 3. C. trachomatis transformants expressing RSGFP, mCherry or CFP from the incD gene promoter.

A–C Maps of the p2TK-SW2 derivatives allowing expression of RSGFP (A), mCherry (B) or CFP (C) from the incDEFG operon promoter. The pSW2 plasmid is shown in black, the E.coli origin of replication in dark grey and the ampicillin resistance cassette (bla) in light grey. The rsgfp (green), mCherry (red) and cfp (blue) ORFs are flanked by the incDEFG operon promoter and terminator (light grey). Unique restriction sites are shown in red. D–F. Immunofluorescence images of C. trachomatis inclusions harboring bacteria expressing RSGFP (D), mCherry (E) or CFP (F) from the incDEFG operon promoter. Scale Bar: 10 µm.

We also tested whether additional fluorescent proteins, mCherry and the Cyan Fluorescent Protein (CFP), could be expressed in C. trachomatis. For this purpose, we created KpnI/NotI DNA fragments where the mCherry or cfp [42] ORFs were flanked by the promoter and terminator regions of the incDEFG operon. The E. coli-C. trachomatis shuttle plasmids, p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm and p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm were respectively obtained by ligation of the IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm or IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm DNA fragments into the KpnI and NotI restriction sites of p2TK2-SW2 (Figure 3B–3C (map), Figure S5–S6 (sequence) and Materials and Methods).

The p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm, p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm and p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm plasmids were then introduced into C. trachomatis as described by Wang et. al. ([37], Materials and Methods). Wild type inclusions were observed after two rounds of penicillin selection. After a third round of selection, the majority of the HeLa cells displayed large wild type inclusions. In addition, C. trachomatis transformed with the plasmids listed above, respectively developed GFP-, mCherry- and CFP-positive inclusions (Figure 3D, 3E and 3F). The analysis of plasmid and genomic DNA from the parental and transformed strains confirmed the episomal status of the transformed plasmids and the integrity of the chromosomal incDEFG locus of the GFP-, mCherry- and CFP-expressing C. trachomatis strains. In addition, we confirmed that the pL2 plasmid had been exchanged for the transformed plasmid (Figure S7).

Altogether, these results indicated that different fluorescent proteins could be expressed in C. trachomatis without apparent impairment of the developmental cycle. Moreover successful expression of the gfp, mCherry or cfp transgenes from the incDEFG promoter was achieved indicating that C. trachomatis transcriptional regulatory elements can be used to drive the expression of transgenes from the transformed plasmids.

C. trachomatis strains expressing RSGFP, mCherry or CFP from the incD promoter replicate as well as the parental strain

We next compared the growth characteristics of the transformed strains expressing GFP, mCherry or CFP, to the parental strain and the strain harboring an empty plasmid.

HeLa cells were infected with the parental strain, C. trachomatis L2 (Figure 4A), or the transformed strains harboring p2TK2-SW2 (Figure 4B), p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm (Figure 4C), p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm (Figure 4D) or p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm (Figure 4E). Infections were performed in the absence (No Pen.) or in the presence (10 U/ml Pen.) of penicillin. Infected cells were fixed 22 h and 33 h post infection and stained with antibodies against Chlamydia Major Outer Membrane Protein (MOMP) to visualize the inclusions. As shown in Figure 4, 22 h post infection all five strains had developed wild type inclusions of equal size in the absence of penicillin (22 h, No Pen.). As the developmental cycle progressed, the size of the inclusion increased equally between the strains (33 h, No Pen.). Except for the parental strain, which displayed aberrant inclusions in the presence of penicillin, all transformed strains were able to develop wild type inclusions in the presence of penicillin (22 h 10 U/ml Pen. and 33 h 10 U/ml Pen.). The MOMP staining showed that even in the absence of penicillin, 100% of the inclusions were GFP- (Figure 4C), mCherry- (Figure 4D) or CFP-positive (Figure 4E), indicating homogeneity of the respective strains and stability of the plasmids for at least one round of infection cycle.

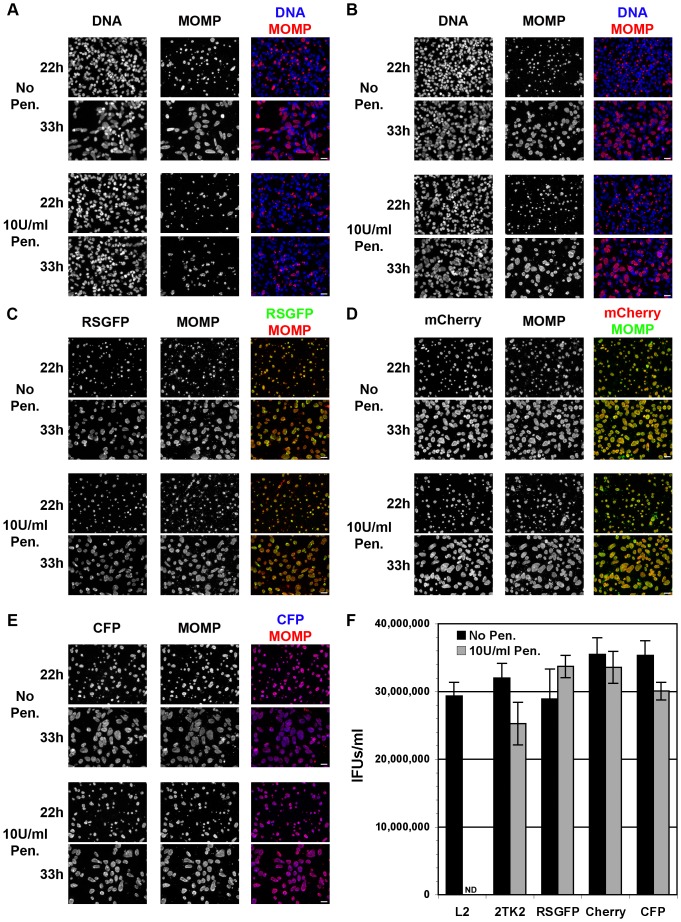

Figure 4. Growth characteristics of C. trachomatis L2 and the transformed strain expressing RSGFP, mCherry or CFP from the incD gene promoter.

A–E HeLa cells were infected with the parental strain, C. trachomatis L2 (A), or the transformed strain harboring p2TK2-SW2 (B), p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm (C), p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm (D) or p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm (E) in the absence (No Pen.) or presence (10 U/ml Pen.) of penicillin. Samples were fixed 22 h and 33 h post infection and stained with the DNA dye Hoechst (A–B) (DNA, left panels) and antibodies against Chlamydia Major Outer Membrane Protein (MOMP) (A–E) (MOMP, middle panels) to visualize the inclusions. GFP (C), mCherry (D) and CFP (E) images are shown on the left panels. The merge images are shown on the right. Scale Bar: 25 µm. F. HeLa cells were infected with the parental strain, C. trachomatis L2 (L2), or the transformed strains harboring p2TK2-SW2 (2TK2), p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm (RSGFP), p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm (Cherry) or p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm (CFP) in the absence (Black bars, No Pen.) or in the presence of penicillin (Grey bars, 10 U/ml Pen.). The number of infectious particles (IFUs) recovered 48 h post infection was determined. ND: Not Detected.

To determine whether the transformed plasmids were stable over time in the absence of penicillin, the mCherry strain was cultured for 20 developmental cycles and the GFP and CFP strains for 10 developmental cycles, in the absence of selection. To determine the homogeneity of the population after 20–10 developmental cycles, the cells were infected with the passaged strains at a MOI of 0.5 and 0.1 for 24 h (not shown). The fixed samples were stained with an antibody against MOMP. For all three strains, 100% of the MOMP-positive inclusions were fluorescent, demonstrating the stability of the plasmid over time, even in the absence of selection.

We next tested whether GFP-, mCherry- or CFP-expressing C. trachomatis produced the same amounts of infectious particles as the parental strain or the strain harboring an empty plasmid. For this purpose, HeLa cells were infected with the parental strain, C. trachomatis L2 (L2), or the transformed strains harboring p2TK2-SW2 (2TK2), p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm (RSGFP), p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm (mCherry) or p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm (CFP) in the absence (No Pen.) or presence (10 U/ml Pen.) of penicillin. The number of infectious particles recovered 48 h post infection was determined. As shown in Figure 4F, the parental strain only produced infectious particles in the absence of penicillin (L2, black bar), whereas the transformed strains produced similar amounts of infectious particles in the absence or presence of the antibiotic (2TK2, RSGFP, mCherry and CFP, black and grey bars respectively). In addition, the number of infectious particles recovered from the transformed strains in the absence or presence of penicillin was similar to the parental strain in the absence of penicillin.

Altogether, these results confirmed that C. trachomatis strains expressing GFP, mCherry or CFP developed inclusions of similar size to the parental strain or a strain harboring an empty plasmid, but also produced similar amount of infectious particles, indicating that expression of fluorescent proteins by C. trachomatis did not impair the progression and completion of the developmental cycle.

C. trachomatis strains expressing RSGFP, mCherry or CFP from the incD promoter recapitulate major features of the C. trachomatis developmental cycle

We next tested whether C. trachomatis strains expressing GFP, mCherry or CFP were able to recapitulate major features observed during the C. trachomatis developmental cycle. For this purpose, HeLa cells infected with fluorescent C. trachomatis strains were fixed 24 h post infection and we analyzed the localization/recruitment of bacterial and host proteins, as well as eukaryotic organelles, to the inclusion membrane by immunofluorescence (Figure 5).

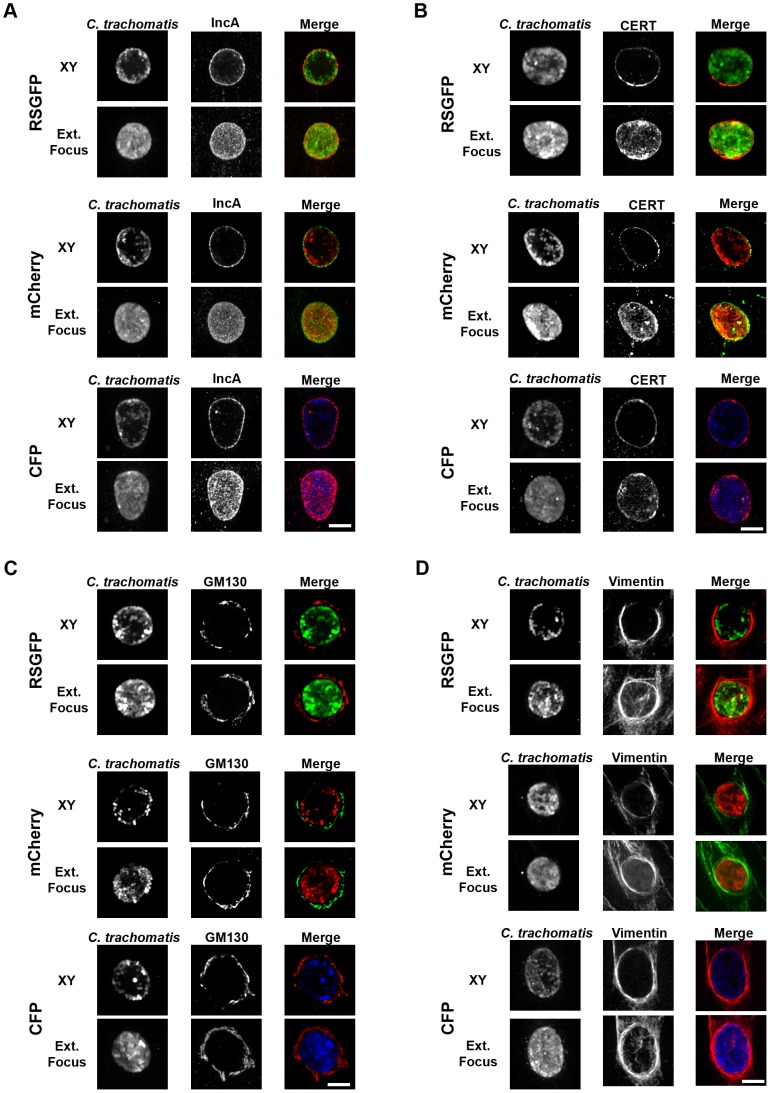

Figure 5. C. trachomatis strains expressing RSGFP, mCherry or CFP from the incD gene promoter recapitulate major features observed during C. trachomatis developmental cycle.

A–D. HeLa cells were infected with C. trachomatis transformed strains harboring p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm (RSGFP), p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm (mCherry) or p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm (CFP) for 24 h. Samples were fixed and stained with antibodies against IncA (A), CERT (B), GM130 (C) and Vimentin (D). Images were acquired using a spinning disc confocal microscope. For each strain and each marker, an XY view (Top panels, XY) and an extended focus view (Bottom Panels, Ext.Focus) are shown. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Using anti-IncA antibodies, we tested whether IncA, a type III effector that belongs to a set of C. trachomatis proteins that are inserted into the inclusion membrane (Inc proteins) [43]–[45], was present in the inclusion membrane (Figure 5A). As a host factor associated with the inclusion membrane, we tested for the presence of the Ceramide transfer protein, CERT ([14], [15]), using anti-CERT antibodies (Figure 5B). Finally, Golgi ministacks and intermediate filaments, two eukaryotic structures known to surround C. trachomatis inclusion [13], [46], were respectively detected using antibodies against GM130 (Figure 5C) and Vimentin (Figure 5D).

As depicted in the extended focus views presented in Figure 5, IncA decorated inclusions harboring GFP-, mCherry- and CFP-expressing C. trachomatis and the XY views confirmed that the IncA signal was restricted to the inclusion membrane. Similarly, CERT was associated with the inclusion membrane where it clustered in small patches as previously observed [14], [15]. In addition, Golgi ministacks were observed all around and in the vicinity of the inclusion as described by Heuer et. al. [13] and the inclusions were also surrounded by a Vimentin cage as described by Kumar et. al. [11].

Altogether these observations indicate that fluorescent C. trachomatis strains recapitulated important features of the C. trachomatis developmental cycle such as translocation and incorporation of type III effectors into the inclusions membrane, association of host proteins with the inclusion membrane and recruitment/manipulation of cellular organelles.

Applications of fluorescent C. trachomatis strains to the study of the developmental cycle

One of the main applications of fluorescent C. trachomatis strains is the study of the developmental cycle using time-lapse video microscopy. It is possible to record mid to late stages of the Chlamydia developmental cycle by phase contrast or differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, because of the characteristic morphology of the inclusion [13], [39], [47], [48]. Alternatively, GFP-expressing cells, in which the Chlamydia inclusion appeared as a black hole, were used to study bacterial release [49]. However, imaging of the early stages of the Chlamydia developmental cycle is challenging, if not impossible.

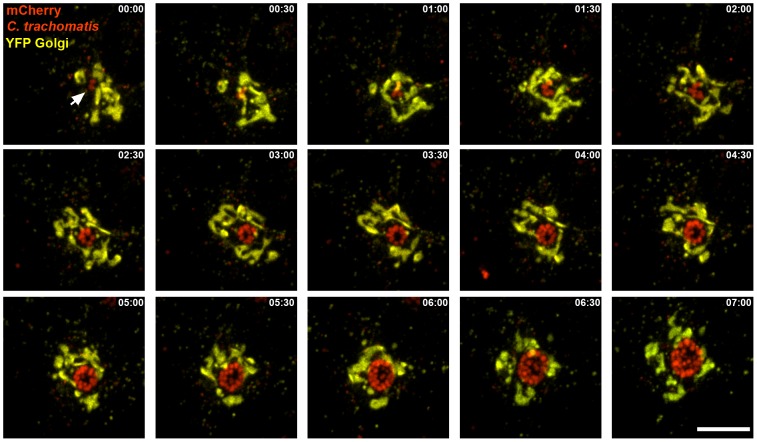

Using the C. trachomatis strain that expressed mCherry under the control of the incD promoter, we were able to image bacterial replication and the early association of the inclusion with the Golgi apparatus (Figure 6 and Video S1). For this purpose, HeLa cells were transfected with a YFP-Golgi construct (Clontech) 18 h prior infection with a C. trachomatis strain that expressed mCherry under the control of the incD promoter. The cells were monitored by spinning-disc confocal microscopy by acquiring series of z-stacks every 30 minutes. As previously described [13], we observed that the inclusion was ultimately surrounded by Golgi ministacks, but the use of a fluorescent C. trachomatis strain allowed us to monitor the early steps of this process (Figure 6 and Video S1). We were able to visualize the expansion of a nascent inclusion that initially contained 2 RBs (Figure 6, 00∶00, white arrow). As the infectious cycle progressed, we visualized bacterial replication leading to an increased number of bacteria that progressively lined up against the inclusion membrane giving the typical ring like pattern (Figure 6, 03∶30). The nascent inclusion was first closely apposed to the Golgi apparatus (Figure 6, 00∶00, white arrow) but very quickly nested itself inside the Golgi apparatus (Figure 6, 01∶00) where it continued to expand, surrounded by the Golgi. This phenomenon was observed in most of the cells that we imaged and suggested that very early on, inclusions containing 2–4 bacteria are already surrounded by the Golgi apparatus and that fragmentation of the Golgi into ministacks happens as the inclusions expand. This is different from previous observations that used phase contrast microscopy to monitor the inclusion and showed Golgi fragmentation after the inclusion had reached a certain size [13]. Both mechanisms are however not incompatible, as Golgi fragmentation might occur more or less early during the developmental cycle. In addition, our data do not contradict the fact that Golgi fragmentation is more apparent at later time point. Overall, our results demonstrate that the fluorescent C. trachomatis strains will be useful to investigate early interaction of the inclusion with host organelles.

Figure 6. Time-lapse video microscopy of the association of C. trachomatis inclusion with the Golgi apparatus during the early stages of the developmental cycle.

Selected merged frames from Video S1 acquired every 30 minutes by time-lapse video microscopy of HeLa cells transiently transfected with a YFP-Golgi construct (yellow) and infected with C. trachomatis expressing mCherry under the control of the incD promoter (red). The first frame corresponds to 10 h post infection. The time (hours: minutes) is indicated in the upper right corner of each frame. Scale Bar: 10 µm.

Finally, we have used the fluorescent C. trachomatis strains to monitore inclusion fusion. Chlamydia inclusions have been shown to undergo homotypic fusion, a process that is inhibited at low temperature and depends on the inclusion protein IncA [44], [50]–[53]. We monitored this process by co-infection of HeLa cells with GFP- and mCherry-expressing C. trachomatis strains.

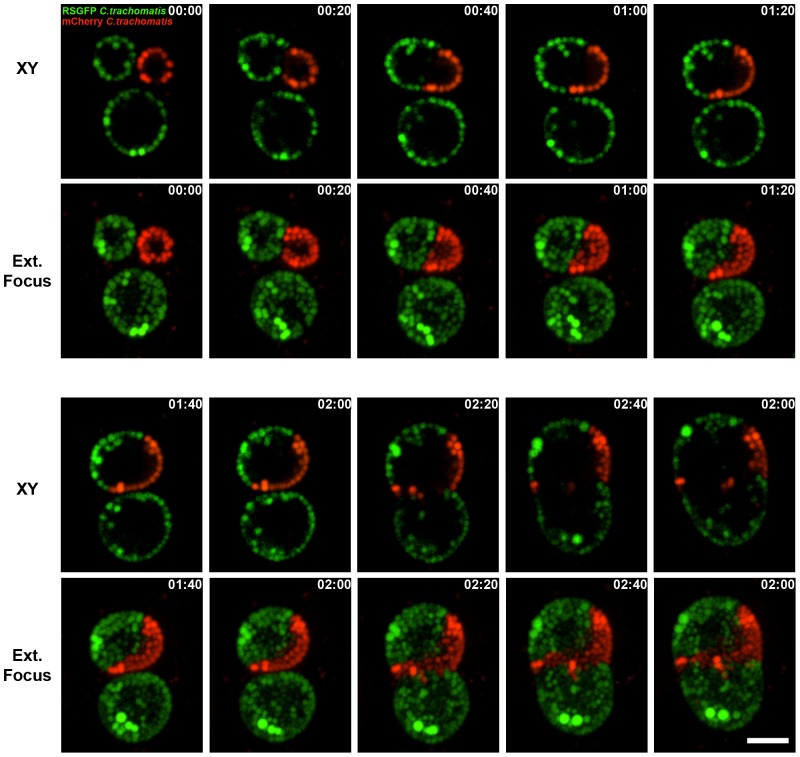

In a first set of experiments, we monitored inclusion fusion 24 h post infection (Figure 7 and Video S2). For this purpose, HeLa cells were co-infected with C. trachomatis strains expressing GFP and mCherry under the control of the incD promoter. The multiplicity of infection was such that 1 to 3 inclusions per cell were observed 24 h post infection. Cells that displayed at least 2 inclusions were then monitored by spinning-disc confocal microscopy 24 h post infection, by acquiring series of z-stacks every 20 minutes. As shown in Figure 7 and Video S2, we were able to monitor inclusion fusion in a cell harboring 2 GFP-positive and 1 mCherry-positive inclusion at the beginning of the acquisition (Figure 7, 00∶00, Video S2). As the infection progressed, one of the GFP-positive inclusions fuses with the mCherry inclusion (Figure 7, 00∶20, Video S2) leading to an inclusion in which GFP-positive bacteria are lined up on one side of the inclusion membrane and mCherry positive bacteria on the other side. As time progressed, the bi-colored inclusion eventually fused with the second GFP positive inclusion (Figure 7, 02∶20, Video S2).

Figure 7. Time-lapse video microscopy of C. trachomatis inclusion fusion.

Selected merged frames from Video S2 acquired every 20 minutes by time-lapse video microscopy of HeLa cells co-infected with C. trachomatis strains expressing GFP (green) or mCherry (red) under the control of the incD promoter. The first frame corresponds to 24 h post infection. For each time point, an XY view (Top panels, XY) and an extended focus view (Bottom Panels, Ext.Focus) are shown. The time (hours: minutes) is indicated in the upper right corner of each frame. Scale Bar: 6 µm.

In a second set of experiments, HeLa cells were co-infected with C. trachomatis strains expressing GFP and mCherry under the control of the incD promoter, at a high multiplicity of infection (∼10 C. trachomatis/HeLa cells). Growth of the bacteria was monitored 10 h post infection by spinning-disc confocal microscopy, by acquiring series of z-stacks every 30 minutes. As shown in Video S3, at the beginning of the acquisition the cells were co-infected with several GFP and mCherry expressing bacteria. As the developmental cycle progressed, both bacterial replication and inclusion fusion occurred. Half way through the movie, the cells harbored several inclusions. Some contained only GFP- or mCherry-positive bacteria making it difficult to determine whether inclusion fusion had occurred. While other inclusions clearly resulted from fusion since they harbored both GFP- and mCherry-positive bacteria. By the end of the movie, each cell harbored a single inclusion containing GFP- and mCherry-positive bacteria and resulting from the fusion of the multiple inclusions observed at earlier time points.

While the fusion of medium to large size inclusion could have been monitored by phase contrast microscopy, the use of fluorescent bacteria allowed visualization of fusion of small inclusions containing few bacteria (Video S3). In addition, the use of bacteria of different colors allowed visualizing the segregation of each strain inside the inclusion (Video S2 and S3). Finally, co-infection with C. trachomatis strains expressing different fluorescent proteins would be a useful tool to unambiguously determine if inclusion fusion occurred by assaying for the presence of bacteria of each color at the end of the developmental cycle.

Conclusions

We have generated versatile vectors for conducting genetic experiments in C. trachomatis. C. trachomatis strains expressing fluorescent proteins from C. trachomatis regulatory element will be useful to study temporal gene expression as well as the early developmental stages of the developmental cycle by time lapse-video microscopy. In addition, our cloning vector will be a valuable tool for mutant complementation as well as expression of wild type, mutated or tagged proteins in C. trachomatis.

Supporting Information

A minimal plasmid for replication in E. coli. Map of p2TK2. The E.coli origin of replication and the ampicillin resistance cassette are respectively shown in dark and light grey. Unique restriction sites of the multiple cloning site are shown in red.

(TIF)

A minimal plasmid for replication in E. coli. p2TK2 Vector Sequence.

(DOC)

A cloning vector for C. trachomatis. p2TK2-SW2 Vector Sequence.

(DOC)

p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm Vector Sequence.

(DOC)

p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm Vector Sequence.

(DOC)

p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm Vector Sequence.

(DOC)

Episomal status of the transformed plasmids and integrity of the incDEFG locus in the transformed strains. A. Plasmids were isolated from the parental strain (L2) and from the transformed strains (mCh, GFP and CFP). The plasmids were digested with the BamHI restriction enzyme. As expected the pL2 plasmid was linearized, leading to a 7,505 bp DNA fragment. Digestion of the plasmids from the transformed strained generated a 7,176 bp DNA fragment, corresponding to the pSW2 plasmid, and to a ∼3,100 bp DNA fragment, corresponding to the p2TK2 plasmid and the insert containing the fluorescent protein gene flanked by the incD promoter and terminator. These results demonstrate the episomal status of the plasmid and the exchange of the pL2 plasmid for the transformed plasmid. B. DNA was isolated from the parental strain (L2) and from the transformed strains (mCh, GFP and CFP). The procedure led to isolation of both genomic and plasmid DNA. The DNA served as a template in PCR reactions using primers annealing upstream and downstream from the incD promoter and terminator respectively, either in the transformed plasmid (P) or the C. trachomatis chromosome (C). Please see the Material and Methods section and Table S1 for the name and sequence of the primers. As expected, when DNA from the mCherry or CFP strains was used as template (mCh and CFP), primers annealing to p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm or p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm led to the amplification of a 1,300 bp DNA fragments corresponding to the mCherry or cfp gene flanked by the incD promoter and terminator. When DNA from the RSGFP strains was used as template (GFP), primers annealing to p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm, led to the amplification of a 1,200 bp DNA fragment, corresponding to rsgfp gene flanked by the incD promoter and terminator. No DNA product was obtained when DNA from the parental strain was used as template (L2). Primers annealing to the chromosome led to the amplification of a 2,200 bp DNA fragment corresponding to the incDEFG operon, when DNA from the parental or the transformed strains was used as template. These results indicate that the incDEFG operon locus is not altered in the transformed strains. C. Southern blot using DNA (genomic and plasmid) isolated from the parental strain (L2) and from the transformed strains (mCh, GFP and CFP). The DNA was digested with the BamHI restriction enzyme and analyzed by Southern blot using probes corresponding to the p2TK2 plasmid or the pSW2 plasmid. As expected, a ∼3,100 bp DNA fragment, corresponding to the p2TK2 plasmid and the insert containing the fluorescent protein gene flanked by the incD promoter and terminator was only detected in samples from the transformed strains with the p2TK2 probe. The SW2 probe led to the detection of a 7,505 bp DNA fragment corresponding to the pL2 plasmid in the parental strain DNA sample and to the detection of a 7,176 bp DNA fragment corresponding to the pSW2 plasmid in the transformed strains DNA samples. These results further confirm the episomal status of the transformed plasmids and demonstrate the exchange of the pL2 plasmid for the transformed plasmid.

(TIF)

Primers used in this study.

(DOC)

Time-lapse video microscopy of the association of C. trachomatis inclusion with the Golgi apparatus during the early stages of the developmental cycle. Video S1 shows the association of C. trachomatis inclusion with the Golgi apparatus that occurs during C. trachomatis infection. HeLa cells were transfected with a YFP-Golgi construct (Yellow) 18 h prior infection with a C. trachomatis strain that expressed mCherry under the control of the incD promoter (red). 10 h post infection, a YFP-Golgi expressing cell was monitored by spinning disc confocal microscopy. A z-stack of 56 images covering 14 µm was acquired every 30 minutes. The QuickTime video was generated using Improvision Volocity. The time (hours: minutes: seconds) is indicated in the upper right corner. The video is played at 2 frames/s. Scale Bar: 3.5 µm.

(MOV)

Time-lapse video microscopy of C. trachomatis inclusion fusion 24 h post infection. Video S2 shows the fusion of inclusions harboring GFP or mCherry expressing C. trachomatis. HeLa cells were co-infected with a C. trachomatis strain that expressed GFP (green) or mCherry (red) under the control of the incD promoter. 24 h post infection, a cell containing 2 GFP- and 1 mCherry-positive inclusion was monitored by spinning disc confocal microscopy. A z-stack of 56 images covering 14 µm was acquired every 20 minutes. The QuickTime video was generated using Improvision Volocity. The time (hours: minutes:seconds) is indicated in the upper right corner. The video is played at 2 frames/s. Scale Bar: 8 µm.

(MOV)

Time-lapse video microscopy of C. trachomatis inclusion fusion. Video S3 shows the fusion of inclusion harboring GFP- or mCherry-expressing C. trachomatis. HeLa cells were co-infected with a C. trachomatis strain that expressed GFP (green) or mCherry (red) under the control of the incD promoter. 10 h post infection, cells containing several GFP- and mCherry-positive bacteria were monitored by spinning disc confocal microscopy. A z-stack of 56 images covering 14 µm was acquired every 30 minutes. The QuickTime video was generated using Improvision Volocity. The time (hours: minutes: seconds) is indicated in the upper right corner. The video is played at 2 frames/s. Scale Bar: 19 µm.

(MOV)

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Wang, S. Kahane, L.T. Cutcliffe, R.J. Skilton, P.R. Lambden and I.N. Clarke for developing the C. trachomatis transformation protocol, T. Hackstadt (Rocky Mountains Laboratories) for providing the anti-IncA antibodies, Xaver Sewald and Arthur Talman for helping with time-lapse video microscopy, Matthew Lefebre for helping with Vector NTI, Hayley Newton for her help with the Southern blot and members of the Agaisse, Roy and Galán Laboratories for critical comments and discussion.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R21 AI088312 to ID. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Friis RR (1972) Interaction of L cells and Chlamydia psittaci: entry of the parasite and host responses to its development. J Bacteriol 110: 706–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moulder JW (1991) Interaction of chlamydiae and host cells in vitro. Microbiol Rev 55: 143–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Betts HJ, Wolf K, Fields KA (2009) Effector protein modulation of host cells: examples in the Chlamydia spp. arsenal. Curr Opin Microbiol 12: 81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cocchiaro JL, Valdivia RH (2009) New insights into Chlamydia intracellular survival mechanisms. Cell Microbiol 11: 1571–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saka HA, Valdivia RH (2010) Acquisition of nutrients by Chlamydiae: unique challenges of living in an intracellular compartment. Curr Opin Microbiol 13: 4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dautry-Varsat A, Subtil A, Hackstadt T (2005) Recent insights into the mechanisms of Chlamydia entry. Cell Microbiol 7: 1714–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elwell CA, Ceesay A, Kim JH, Kalman D, Engel JN (2008) RNA interference screen identifies Abl kinase and PDGFR signaling in Chlamydia trachomatis entry. PLoS Pathog 4: e1000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lane BJ, Mutchler C, Al Khodor S, Grieshaber SS, Carabeo RA (2008) Chlamydial entry involves TARP binding of guanine nucleotide exchange factors. PLoS Pathog 4: e1000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fields KA, Hackstadt T (2002) The chlamydial inclusion: escape from the endocytic pathway. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 18: 221–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scidmore MA, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T (2003) Restricted fusion of Chlamydia trachomatis vesicles with endocytic compartments during the initial stages of infection. Infect Immun 71: 973–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumar Y, Valdivia RH (2008) Actin and intermediate filaments stabilize the Chlamydia trachomatis vacuole by forming dynamic structural scaffolds. Cell Host Microbe 4: 159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hackstadt T, Rockey DD, Heinzen RA, Scidmore MA (1996) Chlamydia trachomatis interrupts an exocytic pathway to acquire endogenously synthesized sphingomyelin in transit from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane. Embo J 15: 964–977. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heuer D, Rejman Lipinski A, Machuy N, Karlas A, Wehrens A, et al. (2009) Chlamydia causes fragmentation of the Golgi compartment to ensure reproduction. Nature 457: 731–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Derre I, Swiss R, Agaisse H (2011) The lipid transfer protein CERT interacts with the Chlamydia inclusion protein IncD and participates to ER-Chlamydia inclusion membrane contact sites. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elwell CA, Jiang S, Kim JH, Lee A, Wittmann T, et al. (2011) Chlamydia trachomatis co-opts GBF1 and CERT to acquire host sphingomyelin for distinct roles during intracellular development. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beare PA, Sandoz KM, Omsland A, Rockey DD, Heinzen RA (2011) Advances in genetic manipulation of obligate intracellular bacterial pathogens. Front Microbiol 2: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maurin M, Raoult D (1999) Q fever. Clin Microbiol Rev 12: 518–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beare PA, Howe D, Cockrell DC, Omsland A, Hansen B, et al. (2009) Characterization of a Coxiella burnetii ftsZ mutant generated by Himar1 transposon mutagenesis. J Bacteriol 191: 1369–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beare PA, Gilk SD, Larson CL, Hill J, Stead CM, et al. (2011) Dot/Icm type IVB secretion system requirements for Coxiella burnetii growth in human macrophages. MBio 2: e00175–00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen C, Banga S, Mertens K, Weber MM, Gorbaslieva I, et al. (2010) Large-scale identification and translocation of type IV secretion substrates by Coxiella burnetii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 21755–21760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beare PA, Larson CL, Gilk SD, Heinzen RA (2012) Two systems for targeted gene deletion in Coxiella burnetii . Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 4580–4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Omsland A, Cockrell DC, Howe D, Fischer ER, Virtaneva K, et al. (2009) Host cell-free growth of the Q fever bacterium Coxiella burnetii . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 4430–4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Driskell LO, Yu XJ, Zhang L, Liu Y, Popov VL, et al. (2009) Directed mutagenesis of the Rickettsia prowazekii pld gene encoding phospholipase D. Infect Immun. 77: 3244–3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baldridge GD, Burkhardt N, Herron MJ, Kurtti TJ, Munderloh UG (2005) Analysis of fluorescent protein expression in transformants of Rickettsia monacensis, an obligate intracellular tick symbiont. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 2095–2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baldridge GD, Burkhardt NY, Oliva AS, Kurtti TJ, Munderloh UG (2010) Rickettsial ompB promoter regulated expression of GFPuv in transformed Rickettsia montanensis . PLoS One 5: e8965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu ZM, Tucker AM, Driskell LO, Wood DO (2007) Mariner-based transposon mutagenesis of Rickettsia prowazekii . Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 6644–6649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Renesto P, Gouin E, Raoult D (2002) Expression of green fluorescent protein in Rickettsia conorii . Microb Pathog 33: 17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kleba B, Clark TR, Lutter EI, Ellison DW, Hackstadt T (2010) Disruption of the Rickettsia rickettsii Sca2 autotransporter inhibits actin-based motility. Infect Immun 78: 2240–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, et al. (1998) Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis . Science 282: 754–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DeMars R, Weinfurter J, Guex E, Lin J, Potucek Y (2007) Lateral gene transfer in vitro in the intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis . J Bacteriol 189: 991–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. DeMars R, Weinfurter J (2008) Interstrain gene transfer in Chlamydia trachomatis in vitro: mechanism and significance. J Bacteriol 190: 1605–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Suchland RJ, Sandoz KM, Jeffrey BM, Stamm WE, Rockey DD (2009) Horizontal transfer of tetracycline resistance among Chlamydia spp. in vitro . Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53: 4604–4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jeffrey BM, Suchland RJ, Quinn KL, Davidson JR, Stamm WE, et al. (2010) Genome sequencing of recent clinical Chlamydia trachomatis strains identifies loci associated with tissue tropism and regions of apparent recombination. Infect Immun 78: 2544–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harris SR, Clarke IN, Seth-Smith HM, Solomon AW, Cutcliffe LT, et al. (2012) Whole-genome analysis of diverse Chlamydia trachomatis strains identifies phylogenetic relationships masked by current clinical typing. Nat Genet 44: 413–419, S411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tam JE, Davis CH, Wyrick PB (1994) Expression of recombinant DNA introduced into Chlamydia trachomatis by electroporation. Can J Microbiol 40: 583–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Binet R, Maurelli AT (2009) Transformation and isolation of allelic exchange mutants of Chlamydia psittaci using recombinant DNA introduced by electroporation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 292–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang Y, Kahane S, Cutcliffe LT, Skilton RJ, Lambden PR, et al. (2011) Development of a transformation system for Chlamydia trachomatis: restoration of glycogen biosynthesis by acquisition of a plasmid shuttle vector. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kari L, Goheen MM, Randall LB, Taylor LD, Carlson JH, et al. (2011) Generation of targeted Chlamydia trachomatis null mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 7189–7193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nguyen BD, Valdivia RH (2012) Virulence determinants in the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis revealed by forward genetic approaches. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 1263–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Derre I, Pypaert M, Dautry-Varsat A, Agaisse H (2007) RNAi screen in Drosophila cells reveals the involvement of the Tom complex in Chlamydia infection. PLoS Pathog 3: 1446–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scidmore-Carlson MA, Shaw EI, Dooley CA, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T (1999) Identification and characterization of a Chlamydia trachomatis early operon encoding four novel inclusion membrane proteins. Mol Microbiol 33: 753–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Andersen JB, Roldgaard BB, Lindner AB, Christensen BB, Licht TR (2006) Construction of a multiple fluorescence labelling system for use in co-invasion studies of Listeria monocytogenes . BMC Microbiol 6: 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bannantine JP, Stamm WE, Suchland RJ, Rockey DD (1998) Chlamydia trachomatis IncA is localized to the inclusion membrane and is recognized by antisera from infected humans and primates. Infect Immun 66: 6017–6021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hackstadt T, Scidmore-Carlson MA, Shaw EI, Fischer ER (1999) The Chlamydia trachomatis IncA protein is required for homotypic vesicle fusion. Cell Microbiol 1: 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li Z, Chen C, Chen D, Wu Y, Zhong Y, et al. (2008) Characterization of fifty putative inclusion membrane proteins encoded in the Chlamydia trachomatis genome. Infect Immun 76: 2746–2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kumar Y, Cocchiaro J, Valdivia RH (2006) The obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis targets host lipid droplets. Curr Biol 16: 1646–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Campbell S, Richmond SJ, Yates P (1989) The development of Chlamydia trachomatis inclusions within the host eukaryotic cell during interphase and mitosis. J Gen Microbiol 135: 1153–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Skilton RJ, Cutcliffen LT, Barlow D, Wang Y, Salim O, et al. (2009) Penicillin induced persistence in Chlamydia trachomatis: high quality time lapse video analysis of the developmental cycle. PLoS One 4: e7723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hybiske K, Stephens RS (2007) Mechanisms of host cell exit by the intracellular bacterium Chlamydia . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 11430–11435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Delevoye C, Nilges M, Dehoux P, Paumet F, Perrinet S, et al. (2008) SNARE protein mimicry by an intracellular bacterium. PLoS Pathog 4: e1000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fields KA, Fischer E, Hackstadt T (2002) Inhibition of fusion of Chlamydia trachomatis inclusions at 32 degrees C correlates with restricted export of IncA. Infect Immun 70: 3816–3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Suchland RJ, Rockey DD, Bannantine JP, Stamm WE (2000) Isolates of Chlamydia trachomatis that occupy nonfusogenic inclusions lack IncA, a protein localized to the inclusion membrane. Infect Immun 68: 360–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Van Ooij C, Homola E, Kincaid E, Engel J (1998) Fusion of Chlamydia trachomatis-containing inclusions is inhibited at low temperatures and requires bacterial protein synthesis. Infect Immun 66: 5364–5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A minimal plasmid for replication in E. coli. Map of p2TK2. The E.coli origin of replication and the ampicillin resistance cassette are respectively shown in dark and light grey. Unique restriction sites of the multiple cloning site are shown in red.

(TIF)

A minimal plasmid for replication in E. coli. p2TK2 Vector Sequence.

(DOC)

A cloning vector for C. trachomatis. p2TK2-SW2 Vector Sequence.

(DOC)

p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm Vector Sequence.

(DOC)

p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm Vector Sequence.

(DOC)

p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm Vector Sequence.

(DOC)

Episomal status of the transformed plasmids and integrity of the incDEFG locus in the transformed strains. A. Plasmids were isolated from the parental strain (L2) and from the transformed strains (mCh, GFP and CFP). The plasmids were digested with the BamHI restriction enzyme. As expected the pL2 plasmid was linearized, leading to a 7,505 bp DNA fragment. Digestion of the plasmids from the transformed strained generated a 7,176 bp DNA fragment, corresponding to the pSW2 plasmid, and to a ∼3,100 bp DNA fragment, corresponding to the p2TK2 plasmid and the insert containing the fluorescent protein gene flanked by the incD promoter and terminator. These results demonstrate the episomal status of the plasmid and the exchange of the pL2 plasmid for the transformed plasmid. B. DNA was isolated from the parental strain (L2) and from the transformed strains (mCh, GFP and CFP). The procedure led to isolation of both genomic and plasmid DNA. The DNA served as a template in PCR reactions using primers annealing upstream and downstream from the incD promoter and terminator respectively, either in the transformed plasmid (P) or the C. trachomatis chromosome (C). Please see the Material and Methods section and Table S1 for the name and sequence of the primers. As expected, when DNA from the mCherry or CFP strains was used as template (mCh and CFP), primers annealing to p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-mCherry-IncDTerm or p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-CFP-IncDTerm led to the amplification of a 1,300 bp DNA fragments corresponding to the mCherry or cfp gene flanked by the incD promoter and terminator. When DNA from the RSGFP strains was used as template (GFP), primers annealing to p2TK2-SW2 IncDProm-RSGFP-IncDTerm, led to the amplification of a 1,200 bp DNA fragment, corresponding to rsgfp gene flanked by the incD promoter and terminator. No DNA product was obtained when DNA from the parental strain was used as template (L2). Primers annealing to the chromosome led to the amplification of a 2,200 bp DNA fragment corresponding to the incDEFG operon, when DNA from the parental or the transformed strains was used as template. These results indicate that the incDEFG operon locus is not altered in the transformed strains. C. Southern blot using DNA (genomic and plasmid) isolated from the parental strain (L2) and from the transformed strains (mCh, GFP and CFP). The DNA was digested with the BamHI restriction enzyme and analyzed by Southern blot using probes corresponding to the p2TK2 plasmid or the pSW2 plasmid. As expected, a ∼3,100 bp DNA fragment, corresponding to the p2TK2 plasmid and the insert containing the fluorescent protein gene flanked by the incD promoter and terminator was only detected in samples from the transformed strains with the p2TK2 probe. The SW2 probe led to the detection of a 7,505 bp DNA fragment corresponding to the pL2 plasmid in the parental strain DNA sample and to the detection of a 7,176 bp DNA fragment corresponding to the pSW2 plasmid in the transformed strains DNA samples. These results further confirm the episomal status of the transformed plasmids and demonstrate the exchange of the pL2 plasmid for the transformed plasmid.

(TIF)

Primers used in this study.

(DOC)

Time-lapse video microscopy of the association of C. trachomatis inclusion with the Golgi apparatus during the early stages of the developmental cycle. Video S1 shows the association of C. trachomatis inclusion with the Golgi apparatus that occurs during C. trachomatis infection. HeLa cells were transfected with a YFP-Golgi construct (Yellow) 18 h prior infection with a C. trachomatis strain that expressed mCherry under the control of the incD promoter (red). 10 h post infection, a YFP-Golgi expressing cell was monitored by spinning disc confocal microscopy. A z-stack of 56 images covering 14 µm was acquired every 30 minutes. The QuickTime video was generated using Improvision Volocity. The time (hours: minutes: seconds) is indicated in the upper right corner. The video is played at 2 frames/s. Scale Bar: 3.5 µm.

(MOV)

Time-lapse video microscopy of C. trachomatis inclusion fusion 24 h post infection. Video S2 shows the fusion of inclusions harboring GFP or mCherry expressing C. trachomatis. HeLa cells were co-infected with a C. trachomatis strain that expressed GFP (green) or mCherry (red) under the control of the incD promoter. 24 h post infection, a cell containing 2 GFP- and 1 mCherry-positive inclusion was monitored by spinning disc confocal microscopy. A z-stack of 56 images covering 14 µm was acquired every 20 minutes. The QuickTime video was generated using Improvision Volocity. The time (hours: minutes:seconds) is indicated in the upper right corner. The video is played at 2 frames/s. Scale Bar: 8 µm.

(MOV)

Time-lapse video microscopy of C. trachomatis inclusion fusion. Video S3 shows the fusion of inclusion harboring GFP- or mCherry-expressing C. trachomatis. HeLa cells were co-infected with a C. trachomatis strain that expressed GFP (green) or mCherry (red) under the control of the incD promoter. 10 h post infection, cells containing several GFP- and mCherry-positive bacteria were monitored by spinning disc confocal microscopy. A z-stack of 56 images covering 14 µm was acquired every 30 minutes. The QuickTime video was generated using Improvision Volocity. The time (hours: minutes: seconds) is indicated in the upper right corner. The video is played at 2 frames/s. Scale Bar: 19 µm.

(MOV)