Abstract

Cumulative prospect theory predicts that losses motivate behavior more than equal gains. Contingency management procedures effectively reduce drug use by placing incentives in direct competition with the drug taking behavior. Therefore, framing incentives as losses, rather than gains should decrease drug use to a greater extent, given equivalent incentives. We examined whether contingent vouchers described as either losses or gains differentially affected smoking abstinence rates. Over 5 consecutive days, participants could either gain $75 per day for verified abstinence or lose $75 per day (initial endowment = $375) for continuing to smoke. As a result, loss-framed participants were more likely to achieve at least one day of abstinence. There was a trend towards loss-framed participants reducing the amount smoked more than gain-framed participants. However, participants in the gain-framed group were more likely to maintain abstinence, once initiated. The results partially support cumulative prospect theory and suggest additional ways to initiate behavior change using incentives, outside of using larger magnitude incentives in contingency management procedures.

Keywords: cigarette smoking, contingency management, cumulative prospect theory, smoking cessation, verbal contingency

1. Introduction

Cumulative prospect theory is a decision making model which, in part, proposes value is relative to a reference point, and not an objective constant (Tversky & Kahneman, 1992). Hence, the way in which a good is described, or framed, will influence how the person evaluates that good. For example, medical treatments described as having a “75% survival rate” are viewed more favorably than those with a “25% mortality rate”, even though they are logically equivalent (Levin, Schnittjer, & Thee, 1988; Marteau, 1989; Wilson, Kaplan, & Schneidermann, 1987). While framing has been applied to many different health behaviors (e.g., sunscreen use decreases your risk of skin cancer vs. not using sunscreen increases your risk of skin cancer [Detweiler, Bedell, Salovey, Pronin & Rothman, 1999]), the actual effect on behavior change has been minimal (Akl, Oxman, Herrin, Vist, Terrenato, Sperati, et al., 2011).

In contrast to framed health messages, there is strong evidence that framing tangible goods (i.e., money) as losses impacts behavior more than comparable gains (Tversky and Kahneman, 1991). This phenomenon has been called loss aversion and is larger when people feel ownership of the good (Novemsky & Kahneman, 2005). Research on this ‘endowment effect’ has been studied by giving half of the participants a tangible good (e.g., a coffee cup) and asking how much they would sell that good for (Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler, 1990). Participants not endowed with the good are asked how much they would pay to acquire that good. On average participants endowed with the good are willing to sell the good for twice as much as subjects that were asked to pay to acquire the good (Novemsky and Kahneman, 2005). This difference has been explained as a loss aversion for the good. Sellers evaluate the endowed good as a loss, whereas buyers evaluate the good as a gain. More importantly, changes in behavior (i.e., the proportion of participants actually exchanging a coffee mug for a candy bar [Knetsch, 1989]) are observed when tangible goods are framed as losses, relative to gains.

Contingency management is a treatment that uses tangible incentives to decrease substance abuse and increase abstinence (see, Higgins, Silverman & Heil, 2008). In these procedures, participants are instructed that in order to gain a contingent incentive (e.g., money) they must either reduce the use of, or completely abstain from using the abused substance. That is, participants have repeated choices between either gaining an incentive or continuing to engage in substance abuse. Increasing the magnitude of the incentive decreases the frequency of substance use (e.g., Lamb, Kirby, Morral, Galbicka & Iguchi, 2004). In the same way that medical treatments can be framed in terms of either survival or mortality, contingent incentives can be framed as incentive gains or losses. Thus, in addition to increasing the incentive’s magnitude, the value of the incentive should also be increased by framing it as a loss.

A study by Roll and Howard (2008) tested whether a contingency management smoking cessation procedure using framed incentives would influence smoking cessation rates. Incentive contingencies were described as either gains or losses in two groups of participants. Thus, loss-framed participants would lose incentives for continued smoking, and gain-framed participants would earn incentives for smoking abstinence. Contrary to loss aversion, results indicated that gain-framed participants were more likely to abstain from smoking for at least 48 hours than loss-framed participants. That is, potentially gaining incentives (i.e., reinforcement) was a more powerful motivator of behavior change than potentially losing incentives (i.e., punishment). However, this procedure included a reset contingency for the gain-framed participants, where failing to abstain reset the next incentive to the lowest amount. One implication of using a reset contingency was that gain-framed participants also had potential losses for failing to abstain from smoking. Thus, losses and gains were not explicitly isolated from each other.

The current experiment was a second attempt to compare the effectiveness of contingent incentives described as either gains or losses to promote smoking cessation in a contingency management procedure. This experiment can also be considered a test between the relative effectiveness of the processes of reinforcement and punishment to change smoking behavior, insomuch as the verbal description of the incentive contingency has a large effect on the obtained behavioral change. We simplified the contingency management procedure by having a fixed incentive amount available for 5 consecutive days without a reset contingency. Thus, gain-framed participants would not have an explicit loss contingency. In addition, we instructed loss-framed participants that they had been endowed with a certain sum of money that could only be lost by smoking. The contingent incentive was $75 for each of five breath CO samples meeting an abstinence criterion of < 3 ppm. We chose $75 as an amount for each incentive based on our previous findings that approximately 50% of participants will initiate abstinence during the first visit with an incentive between $100–75 (Romanowich & Lamb, 2010a).

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Thirty adults were recruited via IRB approved advertisements. These individuals had to provide a breath CO reading of ≥15 ppm at intake; report smoking at least 15 cigarettes per day for at least two years; not be using any other tobacco products; not be using any nicotine replacement products; not have concrete plans to quit smoking in the next six months; be at least 18 years of age; and be able to come to the study site each workday between 7–10 am to give a breath CO sample and answer five brief questions about their smoking behavior during the previous 24 hours. Thirty participants provided informed consent, and five participants were retroactively eliminated from the analysis for using nicotine replacement products during the study. This included two participants from the loss-framed group and three participants from the gain-framed group. Table 1 shows demographic information for the 25 participants included in the study. Participants in the two groups were statistically similar on all but two intake measures. Table 1 shows that a higher proportion of participants in the loss group reported an income of < $15,000/year (Fisher’s Exact test, p < 0.05), and also reported smoking more cigarettes per day (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic Information for Participants

| Frame

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Gain | Loss | |

| Number | 12 | 13 |

| Age [M (SD)] | 39 (13) | 43 (14) |

| Number Caucasian (%) | 5 (42) | 3 (23) |

| Number Female (%) | 4 (33) | 5 (39) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Number Single (%) | 2 (17) | 7 (54) |

| Number Married (%) | 4 (33) | 2 (15) |

| Number Widowed or Divorced (%) | 6 (50) | 4 (31) |

| Employment | ||

| Number Full Time (%) | 7 (58) | 5 (39) |

| Income (US$) | ||

| Number < 15,000 (%) | 0 | 6 (46)* |

| Number 15 – 24,999 (%) | 3 (25) | 2 (15) |

| Number 25 – 34,999 (%) | 5 (42) | 3 (23) |

| Number ≥ 35,000 (%) | 4 (33) | 2 (15) |

| Education | ||

| Number HS or GED (%) | 5 (42) | 5 (39) |

| Number Vo Tech or AA (%) | 3 (25) | 4 (31) |

| Number Bachelors + (%) | 4 (33) | 4 (31) |

| Parents Smoked? | ||

| Number Yes (%) | 9 (75) | 12 (92) |

| Number Dad Only (%) | 2 (22) | 4 (33) |

| Number Mom Only (%) | 2 (22) | 2 (17) |

| Number Both (%) | 5 (56) | 6 (50) |

| Age of | ||

| First cigarette [M (SD)] | 16 (3) | 15 (4) |

| Regular smoker [M (SD)] | 17 (3) | 17 (2) |

| Average | ||

| Cigarettes per day [M (SD)] | 18 (3) | 25 (5)* |

| Intake breath CO ppm [M (SD)] | 22 (9) | 25 (6) |

| Intake salivary cotinine [ng/ml; M (SD)] | 313 (149) | 384 (169) |

p < 0.05

2.2 Procedure

Participants were randomized to either the gain- or loss-framed group by first stratifying each individual by intake breath CO level, which was assessed using a Vitalograph CO monitor (Vitalograph Inc., Lenexa, KS). Intake sessions occurred in the afternoon (12–5pm) for all participants. Stratification placed the first subject in the high breath CO group. Subsequent subjects were placed in the high or low breath CO groups depending on whether their entry breath CO level was above or below the median entry breath CO level collected to date. Subjects delivering a sample on the median were assigned to the high or low breath CO groups in an alternating manner. Subjects in each breath CO group were then randomized to either the gain- or loss-framed group based on a blocking procedure. Each block of 4 subjects contained 2 gain-framed and 2 loss-framed participants. This continued until 30 subjects had been randomly assigned to 2 groups of 15 subjects each.

Each participant was told which group they were assigned to immediately after delivering a breath CO sample during intake. At intake, all participants were given a detailed description of the experimental procedures before giving informed consent. Specifically, gain-framed participants were given the following description of the incentives (loss-framed participants in brackets):

Contingent incentives [deductions] are available for delivery of breath CO samples with < 3 ppm [≥3 ppm] CO during visits 6–10. For each day that you deliver a breath CO sample of < 3 ppm [≥3 ppm] during visits 6–10 (absences included), we will add [deduct] $75.00 to an initial endowment of $0 [$375]. After the 10th visit you will be paid any money added to [not deducted from] that initial endowment.

Participants were told that the half-life of breath CO was 2–8 hours (Benowitz, Jacob, Ahijevych, Jarvis, Hall, et al., 2002), and that most individuals could achieve a breath CO < 3 ppm by not smoking for 24 consecutive hours. After giving informed consent, participants were asked to submit a saliva sample and complete several forms, which included a brief self-developed demographics form and a smoking history and attitudes questionnaire. Participants were not given advice or strategies to aid in their attempt to cut-down or quit smoking. This was done to increase the participant’s attention toward the scheduled incentives instead of other determinants of smoking.

After intake, all participants were expected to deliver one breath CO sample each workday (Monday - Friday; excluding holidays) between 7–10 am at the study site for 10 consecutive visits. The first 5 visits were the baseline phase during which no incentives could be earned. The first baseline visit occurred on the Monday after intake. The last five visits were the incentive phase. Incentives contingent on breath CO levels could be earned by producing a breath CO sample < 3 ppm. The criterion of < 3 ppm was chosen based on previous research, which indicated breath CO values in the range of 3–6 ppm provide the most sensitive level of measurement (i.e., minimizing both false positives and false negatives) for abstinence from smoking when breath CO tests were administered once per day (Javors, Hatch & Lamb, 2005). Participants received $1.00 in cash immediately after submitting a breath CO sample during each visit, regardless of their breath CO level. During the incentive phase, participants were told each time they submitted a breath CO sample exactly how much money they had earned/lost up to that point. A missed visit resulted in a missed earning/automatic loss opportunity. Incentives accrued/not lost throughout the incentive phase were paid on the last day of the incentive phase after the participant submitted a breath CO sample.

At each visit, participants were also asked to complete a short form inquiring about their past day use (on Mondays about the past 3 days) of nicotine replacement products, how many cigarettes they smoked in the past 24 hours, how the outcome of the current breath CO made them feel, and the amount of craving they were experiencing. Participants returned these forms after they were informed about any incentives earned/lost. Participants were told that their answers to these questions would not affect their final payments.

Approximately seven days after the final incentive visit (visit 10) participants were asked to return for a follow-up visit. During follow-up, participants submitted breath CO and saliva samples and answered questions about their smoking behavior over the past week. Participants received $10 for attending the follow-up visit.

3. Results & Discussion

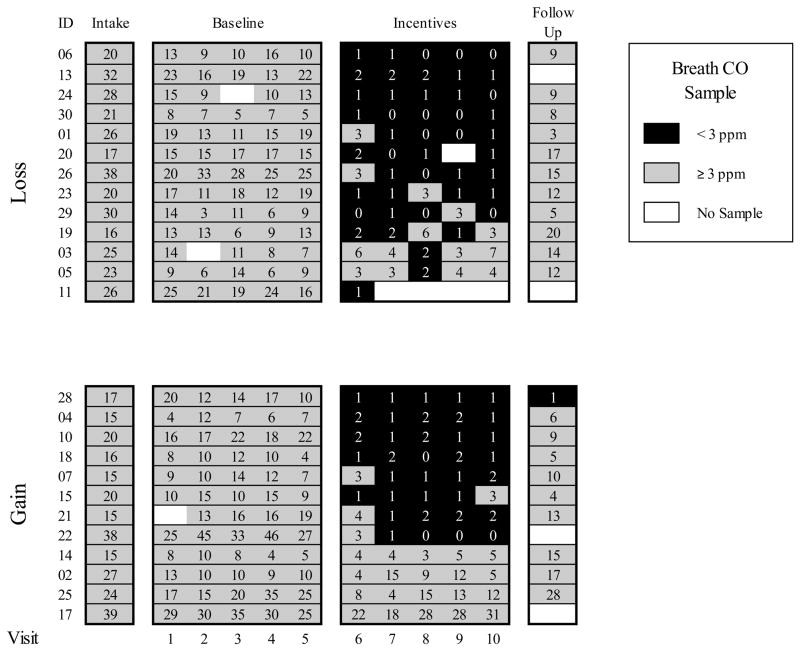

Figure 1 is an event record that shows the individual breath CO samples for each participant. Each row shows individual breath CO samples for a single participant. During the incentive phase, loss-framed participants met the abstinence criterion (< 3 ppm) on 46 of 65 possible visits (71%). Gain-framed participants met the abstinence criterion on 36 of 60 possible visits (60%). All 13 loss-framed participants met the abstinence criterion at least once, whereas only 8 of the 12 gain framed participants did so. The probability of achieving one day of abstinence was significantly greater for participants in the loss-framed group (Fisher Exact, p < 0.05). In addition, during the incentive phase the highest breath CO sample obtained for any loss-framed participant was 7 ppm, which is less than half of the minimum intake level (i.e., 15 ppm). Conversely, three of the 12 gain-framed participants could not maintain this low level (≥7ppm) of smoking. Loss-framed participants also produced more a breath CO sample of 0 (14 vs. 4). During the follow-up phase one gain-framed participant had a breath CO < 3 ppm, whereas no loss-framed participant had a breath CO sample < 3 ppm.

Figure 1.

Event records for loss- and gain-framed participants, where participants could either gain or lose $75 per day. Visit number is shown on the abscissa. The black areas represent visits with a breath CO < 3 ppm, grey areas represent visits with a breath CO ≥3 ppm, and white areas represent missed visits. Each number represents the obtained breath CO sample in ppm across the intake, baseline, incentive and follow-up phases of the experiment.

Figure 2 represents a more conservative measure of how participants’ breath CO samples changed between the baseline and contingent incentive phases. We calculated each incentive breath CO sample as a percentage of the lowest baseline breath CO sample produced by that participant. For example, if a participant’s lowest baseline breath CO sample was 8 ppm, and they had a mean breath CO sample of 2 ppm, the incentive mean would be 25% of the lowest baseline sample. We then ranked each participant, with lower ranks indicative of lower breath CO levels, relative to baseline. This analysis takes into account the best that participants could do with and without contingent incentives. Participant #11 from the loss-framed group was omitted because they only submitted one incentive phase breath CO sample. Consistent with loss aversion, Figure 2 shows that loss-framed participants had a larger mean decrease in breath CO levels during the incentive phase, relative to the baseline phase. This difference reached a trend level of significance (Mann-Whitney, z = 1.62; p = 0.06). The median percent of the lowest baseline breath CO sample was 11% and 26% for loss- and gain-framed participants, respectively.

Figure 2.

Mean incentive phase breath CO samples as a function of the percent of the lowest baseline breath CO sample for each participant. Participants are ranked based on their ability to decrease breath CO values from baseline to the incentive phase of the experiment. Thus, lower ranks are indicative of a lower mean incentive phase breath CO level, relative to their baseline breath CO level. Each point represents one incentive phase breath CO sample. Open circles and open triangles represent loss- and gain-framed participants, respectively.

Previous studies have shown that extended consecutive visits of abstinence at the beginning of treatment, as measured by low breath CO samples, independently predict follow-up abstinence, even when other demographic variables are taken into account (Romanowich & Lamb, 2010b). While all loss-framed participants were able to achieve at least one day of abstinence (see Figure 1), all gain-framed participants that initiated abstinence also maintained that abstinence for at least 4 consecutive visits (8 of 8; 100%). Approximately half of the loss-framed participants were that successful (6 of 13; 46%). This difference in smoking maintenance was significant (Chi-square = 4.27, p < 0.05), and shows that the advantage for describing vouchers as potential gains was more successful for maintaining abstinence.

The current results show that framing the outcome of incentives contingent on a health behavior as a loss can increase the initiation of change in that health behavior. This is consistent with cumulative prospect theory’s proposition that losses motivate behavior more than equal gains. Early tests of cumulative prospect theory provided only one trial for the participant to show their preference. More recently, repeated trials have been used and the results suggest that there is either no change, or small increases in preference for loss-framed alternatives (Morrison, 2000). The current abstinence initiation results are consistent with cumulative prospect theory, while the results for maintaining abstinence are consistent with the results of Roll and Howard (2008). That is, reinforcement is a more powerful motivator than punishment for maintaining smoking abstinence. Taken together, the results suggest that abstinence can be more effectively initiated by potential losses and maintained by potential gains.

While other contingency management studies (e.g., Roll & Higgins, 2000) have also shown that a combination of losses and gains is superior to gains alone for smoking abstinence, no study has started a contingency management procedure with a potential loss and then switched to a potential gain. From the current results, starting the procedure with a potential loss should increase abstinence initiation, while continuing with potential gains should increase abstinence maintenance. Although it is currently unknown if, or how, changing incentives from potential losses to gains (or vice versa) within the same contingency management procedure will affect abstinence, it appears that any procedure that promotes early extended periods of smoking abstinence will lead to less smoking relapse after that procedure ends (Romanowich & Lamb, 2010b).

While the current results are encouraging, there are also several parameters of the experiment that may limit firm conclusions. First, the incentive amount for each day of abstinence was relatively large ($75). It is unknown whether smaller incentive amounts will lead to similar difference reported here. Roll & Howard (2008) used relatively small incentives (starting at $3.00 and increasing by $0.50 for each consecutive abstinent sample) in their study. In fact, there is evidence that small losses do not change behavior more than small gains (Harinck, Van Dijk, Van Beest & Mersmann, 2007). In addition, if the $75/visit contingent incentive was extended for an entire year, the total amount (~$20,000) would be more than the reported earnings of a substantial portion of the participants (see Table 1). A re-analysis showed no apparent difference in participant’s ability to abstain from smoking as a function of reported income. In fact, two of the three gain-framed participants from the lowest self-reported income level did not achieve even one abstinent visit. However, decreasing income is likely to increase a participants motivation to abstain, and should be considered in contingency management procedures.

Second, loss-framed participants never had physical possession of the endowed vouchers. Thus, any effect of losses (or gains) in the current experiments rested on the assumption that loss-framed participants believed they were entitled to the entire sum of money from both our verbal description and the consent form they read. Unfortunately, giving participants the incentives before the intervention has obvious drawbacks. Third, participants in the current study were not looking to quit smoking. Thus, it is unknown how participants motivated to quit smoking before the procedure began would change their behavior with gain- or loss-framed contingent incentives.

Even with these caveats, the median relative change in measured breath CO between the loss- and gain framed participants was approximately a 2:1 ratio, similar to that measured in more traditional loss aversion experiments (Novemsky & Kahneman, 2005).

4. Conclusions

Consistent with cumulative prospect theory, participants who had incentives framed as losses for a brief contingency management smoking cessation procedure were more likely to meet the abstinent breath CO criterion at least once during the incentive phase, relative to participants who had incentives framed as gains. In addition, loss-framed participants decreased their breath CO levels between the baseline and the incentive phase to a greater extent than gain-framed participants. Conversely, once abstinence was initiated, participants in the gain-framed group were more likely to maintain that abstinence than participants in the loss-framed group during the incentive phase. Neither group of participants maintained these breath CO decreases during a follow-up visit. Thus, the additional value of loss-framed incentives for smoking cessation was demonstrated only for the initiation of behavior change.

Highlights.

We framed contingent incentives for smoking cessation as either gains or losses

Loss-framed participants were more likely to initiate abstinence than gain-framed participants

Gain-framed participants were more likely to maintain abstinence, once initiated than loss-framed participants

Participants had similar breath CO levels at a follow-up visit

Acknowledgments

Role of funding sources

The research reported in this paper was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant DA013304 to Dr. R. J. Lamb. This organization had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The authors would like to thank Floyd Jones and Gilbert Holguin for their expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors

Authors Romanowich and Lamb designed the study and wrote the protocol. Author Romanowich conducted literature searches and provided summaries of previous research studies. Authors Romanowich and Lamb conducted the statistical analysis. Author Romanowich wrote the draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akl EA, Oxman AD, Herrin J, Vist GE, Terrenato I, Sperati F, Costiniuk C, Blank D, Schuenemann Framing of health information messages. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;12:CD006777. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006777.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Jacob P, Ahijevych K, Jarvis MF, Hall S, et al. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2002;4:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detweiler JB, Bedell BT, Salovey BT, Pronin E, Rothman AJ. Message framing and sunscreen use: Gain-framed messages motivate beach-goers. Health Psychology. 1999;18:189–196. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harinck F, Van Dijk E, Van Beest I, Mersmann P. When gains loom larger than losses. Psychological Science. 2007;18:1099–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH, editors. Contingency management in substance abuse. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Javors MA, Hatch JP, Lamb RJ. Evaluation of cut-off levels for breath carbon monoxide as a marker for cigarette smoking over the past 24 hours. Addiction. 2005;100:159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Knetsch J, Thaler R. Experimental tests of the endowment effect and the coase theorem. Journal of Political Economy. 1990;98:1325–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Knetsch J. The endowment effect and evidence of nonreversible indifference curves. American Economic Review. 1989;79:1277–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RJ, Kirby KC, Morral AR, Galbicka G, Iguchi MY. Improving contingency management programs for addiction. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:507–523. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin IP, Schnittjer SK, Thee SL. Information framing effects in social and personal decisions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1988;24:520–529. [Google Scholar]

- Marteau TM. Framing of information: Its influence upon decisions of doctors and patients. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1989;28:89–94. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1989.tb00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison GC. WTP and WTA in repeated trial experiments: Learning or leading. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2000;21:57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Novemsky N, Kahneman D. The boundaries of loss aversion. Journal of Marketing Research. 2005;42:119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST. A within-subject comparison of three different schedules of reinforcement of drug abstinence using cigarette smoking as an exemplar. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Howard JT. The relative contribution of economic valence to contingency management efficacy: A pilot study. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:629–633. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanowich P, Lamb RJ. Effects of escalating and descending schedules of incentives in cigarette smoking in smokers without plans to quit. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010a;43:357–367. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanowich P, Lamb RJ. The relationship between in-treatment abstinence and post-treatment abstinence in a smoking cessation treatment. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010b;18:32–36. doi: 10.1037/a0018520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Loss aversion in riskless choice: a reference-dependent model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1991;106:1039–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1992;5:297–323. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DK, Kaplan RM, Schneidermann LJ. Framing of decisions and selections of alternatives in health care. Social Behaviour. 1987;2:51–59. [Google Scholar]