Abstract

The emerging field of vascular composite allotransplantation (VCA) has become a clinical reality. Building upon cutting edge understandings of transplant surgery and immunology, complex grafts such as hands and faces can now be transplanted with success. Many of the challenges that have historically been limiting factors in transplantation, such as rejection and the morbidity of immunosuppression, remain challenges in VCA. Because of the accessibility of most VCA grafts, and the highly immunogenic nature of the skin in particular, VCA has become the focal point for cross-disciplinary approaches to developing novel approaches for some of the most challenging immunological problems in transplantation, particularly the early diagnoses and assessment of rejection. This paper provides a historically oriented introduction to the field of organ transplantation and the evolution of VCA.

1. Organ Transplantation

The concept of replacing organs or limbs that have become diseased or damaged is a deeply rooted human dream so old that it has been incorporated into our mythology in chimeric beings like the Hindu Ganesha [1]. The oldest recorded attempted transplant was the use of skin from a donor to conduct a reconstructive rhinoplasty on another man, performed by the classical Indian surgeon Sushruta, sometime between 1000 and 600 BCE [2–4]. Throughout the ages surgeons have attempted transplantation time and again, but it was not until key contributions from Medawar, Brent, and Billingham at the turn of the 20th century that real progress in understanding the biology underlying host-allograft interactions was made [5–7]. At approximately the same time, important insights into the circulation and role of lymphocytes in immunologic response were being made [8–12]. This essential work came on the heels of important early descriptions of lymphocyte activity in inflammation [13–16].

As the scientific foundations for transplant biology rapidly evolved, the first successful kidney transplant between identical twins was conducted in 1954 [17, 18]. Although a surgical success, little immunologic information was generated because the transplant was not an allograft (or homograft). The monozygotic twins were genetically identical and therefore shared the same major histocompatibility complex (MHC). Rejection rarely occurs in such cases. The identical twin transplant of 1954 was an isograft, immunologically closer to an autograft than an allograft, and the potent issues of allogenicity were left unresolved. It would not be until the 1960s that appreciable graft survival was achieved in MHC mismatched patients [19–22].

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, attempts to control rejection included irradiation of the recipient to neutralize the host immune system [12, 23–27], the administration of azathioprine [19–22], and eventually treatment with antilymphocyte globulin (ALG/ALS) [28–32]. Although these were shown to have beneficial effects on graft survival, morbidities were extensive [33–35], rejection was still a threat [36], and graft-versus-host disease would sometimes overtake patients [37–44].

With the arrival of cyclosporine in the late 1970s, a new era in the clinical viability of transplantation as a therapeutic intervention dawned. Significant improvements in outcome and graft survival were achieved first in liver [45], then in kidney [46] patients. A new class of immunosuppressant cyclosporine was powerful enough to provide the high levels of immunosuppression required for managing transplants, with fewer of the morbidities associated with prior treatment regimens.

However, these improvements came with a price. Cyclosporine was shown to be nephrotoxic over time [47–49], and care still had to be taken to avoid the morbidities associated with a suppressed immune system, such as infection [50]. Despite these drawbacks, the level of clinical improvement cyclosporine offered over previous methods was very compelling, and cyclosporine fueled much of the explosive growth in transplantation during the 1980s and beyond [51–53].

In late 1987 a report from Japan introduced FK-506 (Tacrolimus) as a new and potent immunosuppressive agent [54]. Additional studies rapidly followed in more animal models, confirming FK-506's effectiveness in suppressing and rescuing grafts from rejection [55–61]. Synergistic effects with cyclosporine were also observed [56, 62]. The potency of FK-506, and its synergistic effects with other drugs, would open the door for future therapeutic strategies to leverage immunosuppression dosage as a controller for modulating the tolerance/rejection balance in transplants [63].

The search for cyclosporine's mechanism of action began almost immediately after it was shown to have clinical promise, but it was not until after the introduction and clinical adoption of FK-506 in the early 1990s that both FK-506 and cyclosporine were discovered to inhibit the calcineurin phosphatase pathway [64–67]. Further studies rapidly elucidated additional mechanism details in subsequent years.

Although mainstream clinical practice had vigorously adopted high-dose combination immunosuppression therapy as the treatment of choice because of the specter of rejection, in 1992 the notion that more immunosuppression was not necessarily better emerged. A group of patients were discovered to have become chimeric or developed tolerance towards their allograft [68], helping to elucidate the fact that allografts carried passenger leukocytes that conducted an immune response against the host; much as the host carries out an immune reaction against the allograft [69]. This became known as the double-immune response or clonal exhaustion and deletion [70]. Further investigation of these cases revealed that moderate levels of immunosuppression, carefully timed and tailored to each individual, were at least partially successful in eliminating patient dependence on lifelong immunosuppression [71]. Prior to these observations the clinical view was that the immune response needed to be quashed as early and completely as possible, in order to prevent the leviathan of rejection from emerging. However after the chimeric patients were discovered, the door to the consideration of more nuanced application of immunosuppression was opened.

Organ transplantation has evolved from an essentially nonexistent field to one of the most prominent disciplines in medicine over the last sixty years.

2. Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation

In 1998 the first human hand transplant under current clinical standards of immunosuppression was conducted, making vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA) a performed clinical reality. Over the past decade it has become a treatment option for the many patients suffering from complex tissue injuries or defects not amenable to conventional reconstruction [72]. More than 60 hand/forearm and most recently arm transplants as well as 90 hands and over 20 face transplants performed throughout the world have also shown that allograft survival with good functional outcomes can be routinely achieved after VCA [73–77]. However, despite the fact that surgical procedures and functional outcomes are highly successful, the need for long-term and high-dose immunosuppression to enable graft survival and to treat/reverse acute rejection episodes are the remaining and pace-limiting obstacles to widespread application [78, 79]. The toxicity profile of such drug treatment is considerable and includes serious side effects, such as opportunistic infections, malignancy, and end organ damage [80–83].

VCA recipients are unique in that they undergo a transplant procedure for what is considered to be a nonlife-threatening condition. Therefore, there is a critical need to develop immunosuppression minimization strategies to reduce the risks of chronic immunosuppression.

The skin is the principal target of rejection after VCA transplantation, making it an obstacle to tolerance induction or minimizing immunosuppression. On the other hand, due to its external location, the skin provides a unique clinical opportunity for monitoring, early diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of VCA rejection, including the possibility of therapies applied directly/topically to the skin.

Acute rejection in hand transplantation appears with maculopapular skin lesions, which can be limited to a small area of the skin or can spread over large parts of the transplant [74, 75, 84–87].

Clinical macroscopic manifestations can range from mild pink discoloration or erythema to lichenoid papules, edema, and onychomadesis. The main histological feature of acute rejection is a mononuclear cell infiltrate. It first appears in the perivascular space of the dermis and then spreads to the interface between dermis and epidermis and/or adnexal structures. A perivascular, cellular infiltrate within the epidermis is typical for a moderate grade of rejection with the immunologic response reaching the outermost layer. If rejection is not successfully treated at that stage, necrosis of single keratinocytes can be observed, resulting in focal dermal-epidermal separation and significant graft damage [84, 86, 87]. If rejection progresses further, necrosis and loss of the epidermis, as the ultimate stage of skin rejection, are considered irreversible. However, very limited information is available on the involvement of components other than the skin in this acute rejection process [86]. The histological findings in VCA patients are in line with results from experimental studies indicating that the skin is highly immunogenic and hence the primary/sentinel target for rejection. This is further substantiated by the fact that immunological tolerance can be achieved towards all components of a VCA experimentally except the skin. It was also shown that skin alterations in a VCA are not exclusively limited to alloimmune-mediated injury. The clinical and histopathological features of immune-related and nonrejection processes are potentially overlapping or may coincide with acute rejection. The underlying mechanisms are largely unknown and represent a current major clinical challenge in differentiating between acute rejection and other forms of skin inflammation.

3. Cytokines in the Study of Skin Rejection

Skin rejection is becoming increasingly useful as a platform to study rejection because it is easy to access and can be monitored more consistently than internal organs during the process of rejection. Because of its high immunogenicity skin is a VCA that is prone to frequent and sudden episodes of rejection, much more so than other tissues such as muscle, making it a clinically important tissue to investigate from the perspective of VCA. Insight and understanding of the dynamics of rejection in skin will likely be elucidative for other tissues and lead to a more complete picture of immune system function under conditions of rejection.

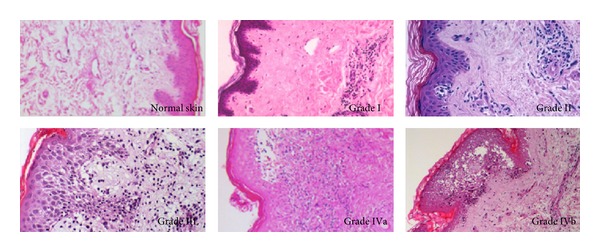

The Banff 97 Working Classification of Renal Allograft Pathology [88] provided a uniform basis for the grading rejection in allograft biopsies. It has been subsequently updated most recently by Banff 07 Classification of Renal Allograft Pathology: Updates and Future Directions [89]. Grading schemes relevant to skin and VCA were also defined in The Banff 2007 Working Classification of Skin-Containing Composite Tissue Allograft Pathology (Figure 1) [85].

Figure 1.

Banff Grading of Acute Skin Rejection in VCA; Allograft histology rejection grades. Grade 0: no or rare inflammatory cells, Grade I: mild perivascular infiltration. No involvement of overlying epidermis, Grade II: moderate. Perivascular inflammation with/without mild epidermal or adnexal involvement (limited to spongiosis and exocytosis). No epidermal dyskeratosis or apoptosis, Grade III: dense inflammation and epidermal involvement with apoptosis, dyskeratosis, and/or keratinolysis, Grade IV: necrotizing acute rejection. Frank necrosis of epidermis or other skin structures.

Interestingly, in our recent unpublished study, in a rat hind limb allograft model we observed a differential rejection pattern in the animals receiving a long-last form of IL-2, IL-2/Fc fusion protein, in combination with antilymphocyte serum and cyclosporine A. Despite all animals undergoing early acute rejection, approximately 55% of them spontaneously recovered and went on to long-term survival for more than 200 days. Moreover, the cytokine and FoxP3 gene expression profiles from the skin biopsy at the earliest sign of rejection revealed a significant increased ratio of FoxP3 expression versus Granzyme, IFN-γ, and Perforin in the animals that spontaneously recovered (benign rejection) as against the animals who had a lower FoxP3 expression that went onto grade 4 rejection (progressive rejection). It suggested that, based on cytokine gene expression profiles from skin biopsy at the earliest sign of rejection, it may be possible to predict the ultimate course of the rejection and provide evidence for a proper treatment (paper in preparation).

4. Similarities in Early Skin Rejection and Other Sources of Skin Inflammation

Skin rejection in VCA is presented with erythematous macules that may progress if not treated to infiltrated scaly violaceous lichenoid papules covering the complete surface of the graft [90]. These alterations are not specific for rejection and may mimic inflammatory dermatoses. Kanitakis et al. emphasized the diagnostic challenges in early or mild skin rejection. Early rejection (grades 1 and 2) can be especially difficult to differentiate from contact dermatitis, insect bites, or dermatophyte infections. It is notable that histologic lesions such as eosinophilia, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and demonstration of infectious antigens can indeed lend specificity to pathologic diagnoses. While the geographic limitation of lesions to the skin of the allograft can be an important and helpful hint, atypical cases of skin rejection with regard to the anatomical site, progression, or the clinical manifestation have been described [91] and the location alone cannot be considered proof. Early and accurate diagnoses, however, are critical to either prevent progression of rejection or incorrect treatment of the patient.

Parallels between acute skin rejection and inflammatory dermatoses (e.g., contact dermatitis, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis) also exist on the molecular and cellular levels. Allergic contact dermatitis, for example, is a T-cell-mediated-delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction that occurs upon hapten challenge in sensitized individuals [92]. Therefore, the differentiation mainly based on histological and macroscopic criteria can be difficult. It has been demonstrated that T cells (CD4+ and CD8+ cells) are critical effectors and that elements of the innate immune system (e.g., natural killer cells) may play a key role [93]. Epidermal Langerhans cells as the most powerful antigen presenting cells in skin as well as keratinocytes are regulating this inflammatory process. Cytokines derived from Langerhans cells (e.g., IL-12) and from T-cells (IFN-gamma, IL-4, and IL-10) play a pivotal role in the induction and initiation of this common skin disease [92, 94].

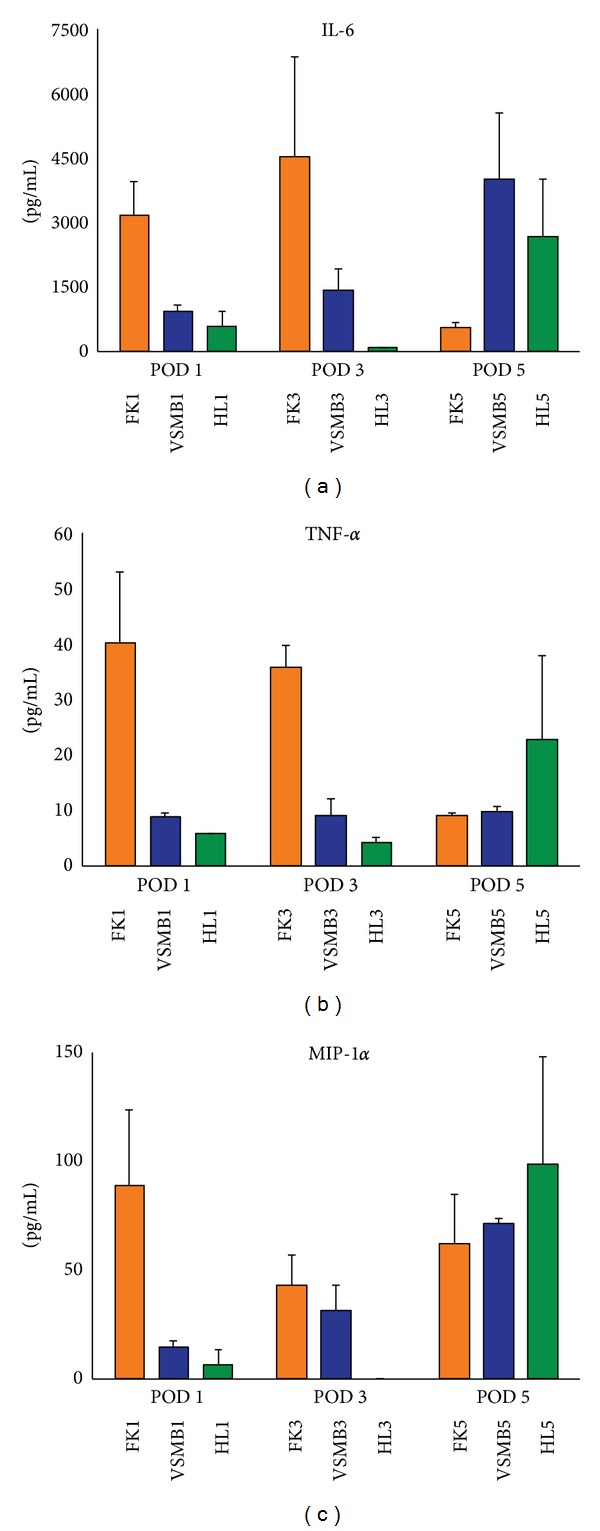

In recently collected unpublished data, cytokine expression patterns associated with rejection-associated inflammation versus non-rejection-associated inflammation in full thickness skin (FTS), vascularized heterotopic skin-muscle-bone (SMB) composite allografts, and hind limb composite allografts are consistently and significantly different. In this model SMB can be engrafted under routine continuous immunosuppression; however, FTS will still be acutely rejected. Through multivariate analysis it was clearly observed that distinct immune signaling patterns mediate rejection in SMB versus FTS. Specific cytokines were observed as the primary drivers of these distinct patterns, and the biological functions of those cytokine ensembles were then elucidated and correlated with the numeric analysis to reveal that rejection-associated inflammation followed clearly different patterns in SMB and FTS [95] (Figure 2, paper in preparation).

Figure 2.

IL-6, TNFα, and MIP-1α are highly expressed from fullness skin (FS) allografts in comparison with that from hind limb (HL) and vascularized skin muscle bone (VSMB) allograft at POD 1 and POD 3.

5. Alternative and Experimental Methods for Detecting Rejection

Interest in finding a better means of detecting or predicting rejection has spawned a range of research approaches. Although these methods have not yet found widespread clinical adoption, the approaches and technical innovations are informative with regards to how challenges faced by the field are being overcome.

Utilizing little or no tissue data, the psychiatric analysis described by [96] concluded that although the features measured could be used to identify certain risk factors for rehospitalization, they were not predictive of rejection specifically. Rehospitalizations were due to a variety of causes, including immunosuppression-associated infection. One of the most predictive factors for rehospitalization included patient noncompliance with medication instructions.

A significant amount of ongoing research is being invested in finding genetic markers for rejection. The most promising results to date have come from [97] showing correlation between miRNA coding for cytotoxic proteins and rejection as well as [98] showing strong correlation between donor gene fragments in circulating blood and the progression of rejection. However, in the presented results there is a high degree of variance in key metrics measured, and the detection of rejection is thought to occur at the onset of graft damage. This may eventually provide an improvement over current clinical standards by reducing unnecessary biopsies and may eventually become a platform for more advanced miRNA-based analytical methods. Additional work in the area of genetic rejection detection has been done by [99, 100].

Cellular analysis is perhaps the most popular alternative approach to assessing rejection. A large number of biomarkers have been identified and catalogued [101] however, in-vivo most biomarkers suffer from high false positive rates or are not cost-effective to assess. For kidney transplant cases, [102] describes a method that is a reliable indicator in about 62% of studied cases. [103] identifies cells associated with rejection in circulating blood, but like [98], these cells provide limited predictive value beyond what may be achieved by pathologist examination of a biopsy.

Doppler tissue imaging as described by [104] may eventually provide a noninvasive alternative to heart biopsy. As described, the system is capable of providing 82% sensitivity and 53% specificity, although it does not confer predictive power.

Significant recent advances in proteomic analysis have been made by [105] who proposed a breath-test for heart transplant rejection that is capable of providing 71.4% sensitivity and 62.4% specificity. Excellent performance in predicting corneal transplant rejection was shown in [106] with the application of linear discriminant analysis to selected cytokines, reinforcing the potential clinical or diagnostic utility of computational and statistical inference methods.

6. Computational and Statistical Inference Literature

The analysis of systems that contain multiple dependent variables, unknown influencing factors, and context dependence presents an especially challenging problem to traditional methods of analysis such as ANOVA or other univariate methods of analysis. To elucidate the actual behavior of complex systems, and to build models with predictive power, more advanced methods of computational and statistical analysis are required. Concise and thorough coverage of the statistical inference and modeling methods that are extensively used in medicine and computational methods of biological analysis is given in [107–110]. Both discriminative and generative methods are important analytical tools in analyzing biological data. Discriminative methods are often able to produce classifiers that have superior performance in predicting class membership than their generative counterparts; however, generative methods allow data to be generated from the model, effectively allowing in silico simulation of system behavior through changes in model parameters. Agent-based models provide a means of understanding complex phenomenon by simulating the behavior of actors within the system, a technique that holds promise for demystifying many biological processes where simulation results can be appropriately constructed, evidentially linked to the biological reality, and experimentally verified. The construction and analysis of this class of computational models are discussed in [111, 112].

Many of the most promising methods and approaches that have the potential to improve the widespread adoption of VCA are at the intersection of medicine, immunology, mathematics, and computer science. By leveraging the strengths and capabilities of each field to solve problems that have been resistant to analysis in another, more rapid progress can be made in delivering novel and clinically relevant findings, diagnostics, or therapeutic compounds.

Approaches that take a cross-disciplinary approach and seek to synthesize the strengths of diverse fields, such as mathematics, computer science, and immunology, are providing new methods and insights that may help to advance the state of the art as well as the development of novel and clinically relevant technologies or therapies for VCA.

Authors' Contribution

X. X. Zheng and S. Schneeberger share equal senior authorship and are to whom correspondence should be addressed.

References

- 1.Narain A. Ganesa: a protohistory of the idea and the icon. In: Brown RL, editor. Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God. Albany, NY, USA: SUNY Press; pp. 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackerknecht EH. A Short History of Medicine. Baltimore, Md, USA: Johns Hopkins University; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauben DJ. Sushruta Samhita (Sushruta’a Collection) (800-600 B.C.?). Pioneers of plastic surgery. Acta Chirurgiae Plasticae. 1984;26(2):65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saraf S. Sushruta: rhinoplasty in 600 BC. The Internet Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2007;3(2):p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medawar PB. The behaviour and fate of skin autografts and skin homografts in rabbits: a report to the War Wounds Committee of the Medical Research Council. Journal of Anatomy. 1944;78, part 5:176–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billingham RE, Brent L, Medawar PB. The antigenic stimulus in transplantation immunity. Nature. 1956;178(4532):514–519. doi: 10.1038/178514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billingham RE, Silvers W. Transplantation of Tissues and Cells. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: The Wistar Institute Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gowans JL. The recirculation of lymphocytes from blood to lymph in the rat. The Journal of Physiology. 1959;146(1):54–69. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farr RS. Experiments on the fate of the lymphocyte. The Anatomical Record. 1951;109(3):515–533. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091090308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry S, Craddock CG, Paul G, Lawrence JS. Lymphocyte production and turnover. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1959;103(2):224–230. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1959.00270020052006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keohane KW, Metcalf WK. Some experiments in fluorescent microscopy designed to elucidate the fate of the lymphocyte. Experimental Physiology. 1958;43(4):408–418. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1958.sp001354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulse EV. Lymphocyte depletion of the blood and bone marrow of the irradiated rat. A quantitative study. British journal of haematology. 1959;5(3):278–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1959.tb04035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunting CH. Fate of the lymphocyte. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1921;33(5):593–600. doi: 10.1084/jem.33.5.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoffey J. The quantitative study of lymphocyte production. Journal of Anatomy. 1933;67, part 2:250–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoffey JM. Variation in lymphocyte production. Journal of Anatomy. 1936;70, part 4:507–514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolouch F., Jr. The lymphocyte in acute inflammation. The American Journal of Pathology. 1939;15(4):413–428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray JE, Merrill JP, Harrison JH, Carpenter CB. Renal homotransplantation in identical twins. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2001;12(1):201–204. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V121201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrill JP, Murray JE, Harrison JH, Guild WR. Successful homotransplantation of the human kidney between identical twins. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1956;160(4):277–282. doi: 10.1001/jama.1956.02960390027008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starzl TE, Marchioro TL, Hermann G, Brittain RS, Waddell WR. Renal homografts in patients with major donor-recipient blood group incompatibilities. Surgical Forum. 1963;14:214–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Starzl TE, Marchioro TL, Waddell WR. The reversal of rejection in human renal homografts with subsequent development of homograft tolerance. Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. 1963;117:385–395. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starzl TE, Marchioro TL, Vonkaulla KN, Hermann G, Brittain RS, Waddell WR. Homotransplantation of the liver in humans. Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. 1963;117:659–976. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray JE, Merrill JP, Harrison JH, Wilson RE, Dammin GJ. Prolonged survival of human-kidney homografts by immunosuppressive drug therapy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1963;268:1315–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196306132682401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hume DM, Magee JH, Kauffman HM, Jr., Rittenbury MS, Prout GR. Renal homotransplantation in man in modified recipients. Annals of Surgery. 1963;158:608–644. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196310000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gleason R, Murray JE. Report from kidney transplant registry: analysis of variables in the function of human kidney transplants. Transplantation. 1967;5(2):343–359. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf JS, McGavic JD, Hume DM. Inhibition of the effector mechanism of transplant immunity by local graft irradiation. Surgery Gynecology & Obstetrics. 1969;128(3):584–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones JM, Wilson R, Bealmear PM. Mortality and gross pathology of secondary disease in germfree mouse radiation chimeras. Radiation Research. 1971;45(3):577–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penn I, Starzl TE. A summary of the status of de novo cancer in transplant recipients. Transplantation Proceedings. 1972;4(4):719–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lwason RK, Ellis LR, Hodges CV. Anti-lymphocyte serum in prolongation of dog renal homografts. Surgical Forum. 1966;17:515–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greaves MF, Roitt IM, Zamir R, Carnaghan RB. Effect of anti-lymphocyte serum on responses of human peripheral-blood lymphocytes to specific and non-specific stimulants in vitro. The Lancet. 1967;2(7530):1317–1319. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(67)90909-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Starzl TE, Groth CG, Brettschneider L. The use of heterologous antilymphocyte globulin (ALG) in human renal and liver transplantation. International Congress Series. 1967;162:83–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray JG, Monaco AP, Russell PS. Heterologous mouse anti-lymphocyte serum to prolong skin homografts. Surgical Forum. 1964;15:142–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huntley RT, Taylor PD, Iwasaki Y, et al. Use of anti-lymphocyte serum to prolong dog homograft survival. Surgical Forum. 1966;17:230–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rifkind D, Marchioro TL, Waddell WR, Starzl TE. Infectious diseases associated with renal homotransplantation. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1964;189:397–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.1964.03070060007001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rifkind D, Starzl TE, Marchioro TL, Waddell WR, Rowlands DT, Hill RB. Transplantation pneumonia. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1964;189:808–812. doi: 10.1001/jama.1964.03070110010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starzl TE, Marchioro TL, Porter KA, Moore CA, Rifkind D, Waddell WR. Renal homotransplantation; late function and complications. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1964;61:470–497. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-61-3-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Starzl TE, Marchioro TL, Brittain RS, Holmes JH, Waddell WR. Problems in renal homotransplantation. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1964;187:734–740. doi: 10.1001/jama.1964.03060230062016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Billingham RE. The biology of graft-versus-host reactions. Harvey Lectures. 1966;62:21–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, et al. Clinical manifestations of graft versus host disease in human recipients of marrow from HL A matched sibling donors. Transplantation. 1974;18(4):295–304. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sale GE, Lerner KG, Barker EA. The skin biopsy in the diagnosis of acute graft versus host disease in man. The American Journal of Pathology. 1977;89(3):621–635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawley TJ, Peck GL, Moutsopoulos HM. Scleroderma, Sjögren-type syndrome, and chronic graft-versus-host disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1977;87(6):707–709. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-87-6-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korngold R, Sprent J. Lethal graft versus host disease after bone marrow transplantation across minor histocompatibility barriers in mice. Prevention by removing mature T cells from marrow. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1978;148(6):1687–1698. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.6.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graze PR, Gale RP. Chronic graft versus host disease: a syndrome of disordered immunity. The American Journal of Medicine. 1979;66(4):611–620. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)91171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. The American Journal of Medicine. 1980;69(2):204–217. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuoka LY. Graft versus host disease. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1981;5(5):595–599. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Starzl TE, Klintmalm GBG, Porter KA. Liver transplantation with use of cyclosporin A and prednisone. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1981;305(5):266–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198107303050507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Group CMTS. A randomized clinical trial of cyclosporine in cadaveric renal transplantation. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1983;309(14):809–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198310063091401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shulman H, Striker G, Deeg HJ. Nephrotoxicity of cyclosporin A after allogeneic marrow transplantation. Glomerular thromboses and tubular injury. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1981;305(23):1392–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198112033052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Myers BD, Ross J, Newton L. Cyclosporine-associated chronic nephropathy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1984;311(11):699–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198409133111103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klintmalm GB, Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. Cyclosporin A hepatotoxicity in 66 renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 1981;32(6):488–489. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198112000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dummer JS, Hardy A, Poorsattar A, Ho M. Early infections in kidney, heart, and liver transplant recipients on cyclosporine. Transplantation. 1983;36(3):259–267. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198309000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colombo D, Ammirati E. Cyclosporine in transplantation—a history of converging timelines. Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents. 2011;25(4):493–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Furukawa H, Todo S. Evolution of immunosuppression in liver transplantation: contribution of cyclosporine. Transplantation Proceedings. 2004;36(2, supplement):274S–284S. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borel JF. History of the discovery of cyclosporin and of its early pharmacological development. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 2002;114(12):433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ochiai T, Nakajima K, Nagata M. Effect of a new immunosuppressive agent, FK 506, on heterotopic cardiac allotransplantation in the rat. Transplantation Proceedings. 1987;19(1):1284–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Venkataramanan R, Warty VS, Zemaitis MA, et al. Biopharmaceutical aspects of FK-506. Transplantation Proceedings. 1987;19(5, supplement 6):30–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeevi A, Duquesnoy R, Eiras G, et al. Immunosuppressive effect of FK-506 on in vitro lymphocyte alloactivation: synergism with cyclosporine A. Transplantation Proceedings. 1987;19(5):40–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Todo S, Podesta L, ChapChap P, et al. Orthotopic liver transplantation in dogs receiving FK-506. Transplantation Proceedings. 1987;19(5, supplement 6):64–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murase N, Todo S, Lee PH, et al. Heterotopic heart transplantation in the rat receiving FK-506 alone or with cyclosporine. Transplantation Proceedings. 1987;19(5, supplement 6):71–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Makowka L, Chapman F, Qian S, et al. The effect of FK-506 on hyperacute rejection in presensitized rats. Transplantation Proceedings. 1987;19(5, supplement 6):79–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nalesnik MA, Todo S, Murase N, et al. Toxicology of FK-506 in the Lewis rat. Transplantation Proceedings. 1987;19(5, supplement 6):89–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thiru S, Collier SDJ, Calne R. Pathological studies in canine and baboon renal allograft recipients immunosuppressed with FK-506. Transplantation Proceedings. 1987;19(5, supplement 6):98–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sanghvi A, Warty V, Zeevi A, et al. FK-506 enhances cyclosporine uptake by peripheral blood lymphocytes. Transplantation Proceedings. 1987;19(5, supplement 6):45–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Starzl TE. New approaches in the use of cyclosporine: with particular reference to the liver. Transplantation Proceedings. 1988;20(3, supplement 3):356–360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schreiber SL, Crabtree GR. The mechanism of action of cyclosporin A and FK506. Immunology Today. 1992;13(4):136–142. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90111-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Russell RGG, Graveley R, Coxon F, et al. Cyclosporin A. Mode of action and effects on bone and joint tissues. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology, Supplement. 1992;21(95):9–18. doi: 10.3109/03009749209101478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Erlanger BF. Do we know the site of action of cyclosporin? Immunology Today. 1992;13(12):487–490. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90023-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Siekierka JJ, Sigal NH. FK-506 and cyclosporin A: immunosuppressive mechanism of action and beyond. Current Opinion in Immunology. 1992;4(5):548–552. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Starzl TE, Demetris AJ, Trucco M, et al. Systemic chimerism in human female recipients of male livers. The Lancet. 1992;340(8824):876–877. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93286-v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rao AS, Starzl TE, Demetris AJ, et al. The two-way paradigm of transplantation immunology. Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology. 1996;80(3, part 2):S46–S51. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Starzl TE, Fung JJ. Themes of liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2010;51(6):1869–1884. doi: 10.1002/hep.23595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shapiro R, Jordan ML, Basu A, et al. Kidney transplantation under a tolerogenic regimen of recipient pretreatment and low-dose postoperative immunosuppression with subsequent weaning. Annals of Surgery. 2003;238(4):520–527. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000089853.11184.53. discussion 525–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dubernard JM, Owen E, Herzberg G, et al. Human hand allograft: report on first 6 months. The Lancet. 1999;353(9161):1315–1320. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lanzetta M, Petruzzo P, Dubernard JM, et al. Second report (1998–2006) of the International Registry of Hand and Composite Tissue Transplantation. Transplant Immunology. 2007;18(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schneeberger S, Ninkovic M, Piza-Katzer H, et al. Status 5 years after bilateral hand transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2006;6(4):834–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cooney WP, Hentz VR, Breidenbach WC, Jones JW. Successful hand transplantation—one-year follow-up. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(1):p. 65. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schuind F, Van Holder C, Mouraux D, et al. The first Belgian hand transplantation–37 month term results. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2006;31(4):371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Petruzzo P, Badet L, Gazarian A, et al. Bilateral hand transplantation: six years after the first case. American Journal of Transplantation. 2006;6(7):1718–1724. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schneeberger S, Zelger B, Ninkovic M, Margreiter R. Transplantation of the hand. Transplantation Reviews. 2005;19(2):100–107. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schuind F, Abramowicz D, Schneeberger S. Hand transplantation: the state-of-the-art. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2007;32(1):2–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stratta RJ. Simultaneous use of tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil in combined pancreas-kidney transplant recipients: a multi-center report. The FK/MMF Multi-Center Study Group. Transplantation Proceedings. 1997;29(1-2):654–655. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(96)00383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hettiaratchy S, Randolph MA, Petit F, Andrew Lee WP, Butler PEM. Composite tissue allotransplantation—a new era in plastic surgery? British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2004;57(5):381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gander B, Brown CS, Vasilic D, et al. Composite tissue allotransplantation of the hand and face: a new frontier in transplant and reconstructive surgery. Transplant International. 2006;19(11):868–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.First MR, Peddi VR. Malignancies complicating organ transplantation. Transplantation Proceedings. 1998;30(6):2768–2770. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00805-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cendales LC, Kirk AD, Moresi JM, Ruiz P, Kleiner DE. Composite tissue allotransplantation: classification of clinical acute skin rejection. Transplantation. 2006;81(3):418–422. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000185304.49987.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cendales LC, Kanitakis J, Schneeberger S, et al. The Banff 2007 working classification of skin-containing composite tissue allograft pathology. American Journal of Transplantation. 2008;8(7):1396–1400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schneeberger S, Lucchina S, Lanzetta M, et al. Cytomegalovirus-related complications in human hand transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;80(4):441–447. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000168454.68139.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Steinmuller D. Skin allograft rejection by stable hematopoietic chimeras that accept organ allografts still is an enigma. Transplantation. 2001;72(1):8–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200107150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB, et al. The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney International. 1999;55(2):713–723. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Solez K, Colvin RB, Racusen LC, et al. Banff 07 classification of renal allograft pathology: updates and future directions. American Journal of Transplantation. 2008;8(4):753–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kanitakis J, Jullien D, Nicolas JF, et al. Sequential histological and immunohistochemical study of the skin of the first human hand allograft. Transplantation. 2000;69(7):1380–1385. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200004150-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schneeberger S, Kreczy A, Brandacher G, Steurer W, Margreiter R. Steroid- and ATG-resistant rejection after double forearm transplantation responds to Campath-1H. American Journal of Transplantation. 2004;4(8):1372–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gober M, Gaspari A. Allergic contact dermatitis. Current Directions in Autoimmunity. 2008;10:1–26. doi: 10.1159/000131410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Saint-Mezard P, Bérard F, Dubois B, Kaiserlian D, Nicolas JF. The role of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in contact hypersensitivity and allergic contact dermatitis. European Journal of Dermatology. 2004;14(3):131–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pastore S, Mascia F, Mariotti F, Dattilo C, Girolomoni G. Chemokine networks in inflammatory skin diseases. European Journal of Dermatology. 2004;14(4):203–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Starzl R, Zhang W, Wang Y, et al. Distinctive cytokine expression during rejection in rat vascularized composite allograft, skin-muscle-bone, and full thickness skin. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Owen JE, Bonds CL, Wellisch DK. Psychiatric evaluations of heart transplant candidates: predicting post-transplant hospitalizations, rejection episodes, and survival. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(3):213–222. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li B, Hartono C, Ding R, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of renal-allograft rejection by measurement of messenger RNA for perforin and granzyme B in urine. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(13):947–954. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103293441301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Snyder TM, Khush KK, Valantine HA, Quake SR. Universal noninvasive detection of solid organ transplant rejection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(15):6229–6234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013924108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sindhi R, Higgs BW, Weeks DE, et al. Genetic variants in major histocompatibility complex-linked genes associate with pediatric liver transplant rejection. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(3):830–839. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lande JD, Patil J, Li N, Berryman TR, King RA, Hertz MI. Novel insights into lung transplant rejection by microarray analysis. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2007;4(1):44–51. doi: 10.1513/pats.200605-110JG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jain KK. The Handbook of Biomarkers. Totowa, NJ, USA: Humana Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kotb M, Russell WC, Hathaway DK, Gaber LW, Gaber AO. The use of positive B cell flow cytometry crossmatch in predicting rejection among renal transplant recipients. Clinical Transplantation. 1999;13(1):83–89. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.130104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bishop GA, Hall BM, Duggin GG, Horvath JS, Sheil AG, Tiller DJ. Immunopathology of renal allograft rejection analyzed with monoclonal antibodies to mononuclear cell markers. Kidney International. 1986;29(3):708–717. doi: 10.1038/ki.1986.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stengel SM, Allemann Y, Zimmerli M, et al. Doppler tissue imaging for assessing left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in heart transplant rejection. Heart. 2001;86(4):432–437. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.4.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Phillips M, Boehmer JP, Cataneo RN, et al. Prediction of heart transplant rejection with a breath test for markers of oxidative stress. American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;94(12):1593–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Maier P, Heizmann U, Böhringer D, Kern Y, Reinhard T. Predicting the risk for corneal graft rejection by aqueous humor analysis. Molecular Vision. 2011;17:1016–1023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wasserman L. All of Statistics: A Concise Course in Statistical Inference. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2010. (Springer Texts in Statistics). [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wasserman L. All of Nonparametric Statistics. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2010. (Springer Texts in Statistics). [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schwartz R. Biological Modeling and Simulation: A Survey of Practical Models, Algorithms, and Numerical Methods. 1st edition. Cambridge, Mass, USA: The MIT Press; 2008. (Computational Molecular Biology). [Google Scholar]

- 110.Schlick T. Molecular Modeling and Simulation: An Interdisciplinary Guide. 2nd edition. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2010. (Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics). [Google Scholar]

- 111.Railsback SF, Grimm V. Agent-Based and Individual-Based Modeling: A Practical Introduction. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Allen TT. Introduction to Discrete Event Simulation and Agent-Based Modeling. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]