Abstract

Background

Increasingly, hospitals are implementing multi-faceted programs to improve medication reconciliation and transitions of care, often involving pharmacists.

Objective

To help delineate the optimal role of pharmacists in this context, this qualitative study assessed pharmacists’ views on their roles in hospital-based medication reconciliation and discharge counseling. We also provide pharmacists’ recommendations for improving care transitions.

Methods

Eleven study pharmacists at two hospitals who participated in the Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease (PILL-CVD) study completed semi-structured one-on-one interviews, which were coded systematically in NVivo. Pharmacists provided their perspectives on admission and discharge medication reconciliation, in-hospital patient counseling, provision of simple medication adherence aids (e.g., pill box, illustrated daily medication schedule), and telephone follow-up.

Results

Pharmacists considered medication reconciliation, though time-consuming, to be their most important role in improving care transitions, particularly through detection of errors in the admission medication history that required correction. They also identified patients with poor understanding of their medications, who required additional counseling. Providing adherence aids was felt to be highly valuable for patients with low health literacy, though less useful for patients with adequate health literacy. Pharmacists noted that having trained administrative staff conduct the initial post-discharge follow-up call to screen for issues and triage which patients needed pharmacist follow-up was helpful and an efficient use of resources. Pharmacists’ recommendations for improving care transitions included clear communication among team members, protected time for discharge counseling, patient and family engagement in discharge counseling, and provision of patient education materials.

Conclusion

Pharmacists are well-positioned to participate in hospital-based medication reconciliation, identify patients with poor medication understanding or adherence, and provide tailored patient counseling to improve transitions of care. Additional studies are needed to confirm these findings in other settings, and to determine the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of different models of pharmacist involvement.

Keywords: pharmacist, health literacy, care transitions, medication reconciliation, qualitative research

As hospitals implement programs to improve transitions of care and reduce hospital readmission, it is important to understand the optimal role that pharmacists may play in such efforts. Decreases in hospital length of stay and high patient acuity have made the discharge process and post-discharge treatment plan increasingly important and complex.1,2 Often, patients are discharged with new medications and changes to their previous regimen.3 Medication discrepancies, non-adherence, and adverse drug events (ADEs) are common in the post-discharge period.4–6 Most ADEs could be ameliorated or prevented through better communication and coordination of care.7 Nevertheless, approximately 20% of elderly patients are rehospitalized within 30 days of discharge,8 prompting myriad initiatives that seek to reduce rehospitalizations and improve other aspects of the hospital discharge transition.9

Efforts to improve medication safety, such as medication reconciliation, comprise an important component of care transition interventions. Medication reconciliation is “a process of identifying the most accurate list of all medications a patient is taking… and using this list to provide correct medications for patients anywhere within the health care system.”10 The Joint Commission recognizes the importance of medication reconciliation, at the same time acknowledging challenges in its implementation.11 Pharmacists are well-suited to improve medication safety, both during hospitalization and the transition from hospital to home.12 Adding clinical pharmacist services to inpatient care, particularly by taking patient medication histories, participating in patient rounds, performing medication reconciliation, or providing discharge counseling and follow-up has been shown to improve patient satisfaction, as well as in-hospital and post-discharge outcomes.12–15

To our knowledge no research has captured pharmacists’ perspectives on their involvement in improving care transitions. Here we present a qualitative evaluation of pharmacists’ experiences in the Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease (PILL-CVD) study, a two-site randomized trial to reduce serious medication errors after hospital discharge.16 This qualitative evaluation sought to: i) examine the key experiences and perspectives of pharmacists about the delivery of a care transition intervention; ii) determine differences and similarities in pharmacists’ experiences implementing the intervention; and iii) identify recommendations for future care transition interventions. These pharmacists’ perspectives offer insights into how to improve care transitions in general, and how best to engage pharmacists in patient counseling, medication reconciliation, and patient follow-up after discharge.

Methods

Semi-structured, one-on-one interviews were completed with the PILL-CVD study pharmacists at both sites to elicit their perspectives on the intervention components and pharmacists’ roles in improving care transitions.

Overview of the PILL-CVD Intervention

PILL-CVD was performed at two academic hospitals – Vanderbilt University Hospital (VUH) and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH). Study participants (n=851) were adults admitted with acute coronary syndromes or acute decompensated heart failure. Patients who did not manage their own medications, or who were not expected to be discharged to home, were excluded. During enrollment, participants completed measures of health literacy17 and cognitive function,18 the results of which were provided to study pharmacists for intervention patients. A complete description of the patient eligibility criteria, study design, and procedures is reported elsewhere.16

PILL-CVD participants were randomized to receive usual care or an intervention which consisted of i) pharmacist-assisted medication reconciliation at admission and discharge; ii) pharmacist-led counseling early in the hospitalization; iii) pharmacist-led discharge counseling; and iv) a 1–4 day follow-up call conducted by the study coordinator, with subsequent pharmacist follow-up if warranted.15,16 Prior to implementing the intervention, pharmacists participated in training sessions that reviewed best practices for taking a medication history, performing medication reconciliation, and counseling patients.19 They also received individualized feedback on their counseling techniques and were required to demonstrate competency.

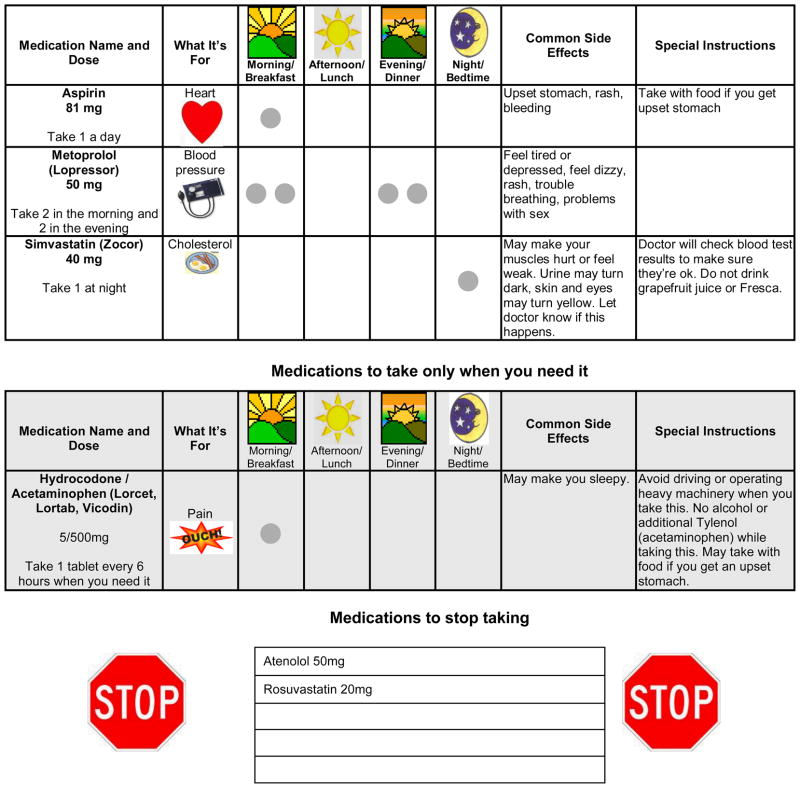

During the study, pharmacists followed protocols to help ensure consistency of intervention delivery. For medication reconciliation, they compiled a thorough medication history from multiple sources at the time of admission, alerted the treating physicians about any clinically relevant discrepancies, and performed reconciliation of discharge medications at the time of discharge. The initial counseling session, which usually overlapped with taking the admission medication history, provided pharmacists an opportunity to assess patients’ understanding of the pre-admission medication regimen, understanding of prescription drug labels, level of adherence, barriers to medication management, and social supports. During the discharge session, pharmacists provided counseling that was tailored to patients’ specific needs and the discharge regimen ordered by the treating physicians, using strategies for clear health communication such as teach-back. At that time, pharmacists also provided patients with an illustrated medication schedule that depicted their daily regimen in a simple format (See Figure in online appendix), and offered a pill box. After discharge, a research coordinator called patients and followed a structured interview to screen for medication-related problems, and to determine which patients needed to be called back by a pharmacist (e.g., to address discrepancies, non-adherence, or side effects).

Qualitative Evaluation

To understand pharmacists’ experience of delivering a care transitions intervention, one author (AO) conducted one-on-one, in-person interviews with study pharmacists (n=11). This qualitative approach allowed us to explore pharmacists’ views, and to probe for their recommendations. To guide the interviews, the authors (KTH, AO) developed a semi-structured manual which provided clear aims and questions for data collection with provisions for following up on participants’ responses (Appendix A). The interview guide focused on the PILL-CVD intervention components and followed an expanded version of the RE-AIM (Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) evaluation framework that was developed for this study.20

Pharmacists were asked about their training to deliver the intervention, the implementation and effectiveness of the intervention, how it fit within their roles, and suggestions to improve delivery of care transition interventions generally. They also were asked about any lasting changes in their own approach to patient assessment and counseling, as a result of their involvement in this initiative. Follow-up probes, both planned and spontaneous, were used to clarify responses.

Pharmacists provided written informed consent to be interviewed and audio-recorded. Interviews were transcribed using Express Scribe (v5.04) online transcription software. Pharmacist names were converted to pseudonyms during transcription.

Transcripts were analyzed using NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software program.21 Coding was based in the RE-AIM evaluation framework, focusing on the domains of efficacy, adoption, and implementation, and followed the structure of the interview guide. Emergent themes were incorporated as well. AO and KTH initially coded each transcript and then discussed and reconciled discrepant coding. AO wrote up thematic analyses assessing the range of perspectives on each coding theme and variations within the themes. KTH reviewed and revised each thematic summary and compared themes across the two sites to gain deeper understanding of program implementation in each setting. KTH and AO culled illustrative quotes from the interview data to include in the thematic analyses. The thematic analyses were used to compile a summary document and executive summary of the findings from the pharmacist interviews, which served as the basis for this manuscript.

Results

Interviews took place between April 1 and June 4, 2010 and ranged from 34 to 67 minutes. Results of the qualitative analysis are organized according to the major components of the intervention, followed by pharmacists’ recommendations for improving care transitions.

Intervention Components

Medication Reconciliation

Pharmacists considered medication reconciliation the most important component of the multifaceted intervention, and the most important way for pharmacists to engage in improving care transitions. Taking a complete medication history and reviewing medications with patients not only provided an opportunity to identify and correct errors in the patient’s medical record, but also helped avert potential adverse drug events. As one pharmacist noted, “You always find something on there that needs to be changed or clarified.”

Pharmacists felt that the accuracy of the pre-admission medication list (PAML) documented by treating physicians varied for different reasons, including when and where the medication history was taken, whether the patient was fully alert at the time, and whether the patient or family had an updated medication list for reference. VUH pharmacists more often reported catching medication errors, compared to pharmacists at BWH, where, prior to the PILL-CVD study, pharmacists were already involved in medication reconciliation. No other differences between pharmacists from the two sites were noted.

Pharmacists reported using various means to develop accurate medication lists including patient or family member recall, patients’ home medication lists, reviewing the documented PAML again with patients, and contacting local pharmacies. One pharmacist indicated that medication reconciliation is “a big concern still and even after doing the study it makes me realize that much more how big of a problem it really is.”

Pharmacists described other positive consequences of conducting detailed medication reconciliation including that it: i) helped clarify medication information for patients, ii) helped patients communicate with their physicians about the medications, and iii) improved the efficiency of ordering medications at discharge. Pharmacists also noted that, because the process of performing a detailed medication review identified patients’ knowledge gaps, medication reconciliation also set the stage for tailored discharge counseling. One problem that pharmacists noted, however, was the amount of time required to adequately perform medication reconciliation.

Initial Counseling Session

Pharmacists felt that their patient counseling session early during the patients’ hospitalization provided a valuable opportunity to gather background information and lay the groundwork for discharge counseling. Not only did pharmacists learn about patients’ specific needs, but by getting patients to think about their medications, the initial counseling facilitated patients being more engaged in subsequent counseling. One pharmacist described the initial counseling session, saying it “helped make the discharge counseling more efficient.” Another pharmacist commented, “[t]he initial counseling is always important because you find out from the patient what the patient is really taking even though you have this list of medications. Sometimes the patients don’t really take that or they just don’t take it appropriately, so it’s always good to talk to the patient instead of just looking at the paper.”

Pharmacists used a data collection form to guide the patient interview. This form promoted adherence to the study protocol and provided a place for pharmacists to document patients’ understanding of the medication regimen, ability to comprehend a pill bottle label, medication adherence, barriers, and supports. Some pharmacists found the forms useful, while others noted they were time consuming or cumbersome.

Pharmacists reported that the most important question they asked patients in the initial counseling session was, “During the week before you were in the hospital, how many days did you miss taking one of your medicines?” This question was part of the counseling protocol and helped pharmacists identify and start to address non-adherence. Pharmacists also found it useful to show patients a sample pill bottle label to determine patients’ comprehension of medication container labels. This, too, was part of the counseling protocol and helped pharmacists tailor their subsequent counseling.

Pharmacists reported that most patients were receptive to this counseling session, although barriers sometimes existed. Patient availability was an issue at both sites; patients were sometimes too tired to receive the initial counseling session, out of the room, or having a procedure. Other times, sessions got interrupted by other aspects of medical care, which led to piecemeal efforts to complete the initial counseling session. One pharmacist indicated that patients’ mental status (e.g., delirium) or use of pain medication limited patients’ ability to participate and required the pharmacist to return at a later time. In general, pharmacists found that the initial counseling session allowed them to build rapport, motivate patients, establish an accurate medication list, and understand patients’ barriers to medication use, all of which enhanced subsequent interactions and counseling. Pharmacists also took the opportunity to encourage family members to be present at the time of discharge, to better assist the patient with handling medications upon returning home.

Discharge Counseling Session

Study pharmacists uniformly found that the discharge counseling session helped patients understand their new medication regimen. This counseling session, which occurred after the treating physician had written the prescriptions, included several components per the protocol: review of the discharge medications, discussing a plan for filling new prescriptions, anticipating and troubleshooting barriers to adherence, provision of adherence aids, and teach-back to confirm understanding. One pharmacist reported that the “discharge was more of the meat [of the intervention] than the initial session.” Another pharmacist relayed that she “had patients who took notes and [realized they had been] taking their medications wrongly for all their lives…” Patients relayed that they did not know that they had to take certain medications at a given time or that they could not drink juice with certain medications, for example.

Pharmacists reported that the in-depth review of discharge medications was the most beneficial component of the discharge counseling sessions. This review was facilitated by provision of an illustrated medication schedule, which pharmacists prepared immediately before the session.16,22 The illustrated medication schedule showed the complete medication regimen with the indication, dose, frequency, main side effects, and any special instructions for each medication (See online Figure). Pharmacists used it to review the discharge medication instructions, while highlighting changes compared to the pre-admission regimen. Pharmacists felt it was important to focus on such changes. One pharmacist commented that “a lot of times, [patients] are taking the same drug, but the dosage has just been slightly modified and sometimes I feel like [that] information is usually not communicated as clearly as if you’re starting a new drug.”

Study pharmacists from both sites reported that it was sometimes challenging to determine whether patients needed a focused review, versus a complete review of medications. The study protocol called for a complete review with teach-back of key elements, but this appeared unnecessary for some patients. When patients had many medications, a complete review could be time-consuming. Pharmacists therefore had mixed feelings about routine use of teach-back. Although most pharmacists enjoyed using this technique and incorporated it effectively into their counseling, they at times felt patients were not receptive to it, or that it felt awkward. The latter occurred when patients either did not understand their medication regimen at all, in which case it could be frustrating, or when the patient understood it very well, in which case it seemed like an unnecessary test.

Pharmacists reported other challenges when performing discharge counseling. First, time pressures were often palpable. Patients who were eager to leave the hospital quickly were less receptive to counseling, and at times, even became frustrated. One pharmacist reported feeling pressured because of the hospital’s desire to clear the room for the next patient. As a result of such time pressures, pharmacists sometimes had to cut short the session, focusing just on changes in the medication regimen. For example, one pharmacist reported that “we mostly got the key stuff in but just knowing that they’re sitting there, you’re frantically trying to get everything ready” [for them to be discharged]. Second, pharmacists sometimes suspected that patients did not ask as many questions as they should have, even though the pharmacists had been trained specifically on how to effectively elicit questions from patients.19 These issues notwithstanding, study pharmacists regarded discharge counseling as important for patient health, even though patients and hospital staff sometimes perceived the discharge counseling session as slowing the discharge process.

Medication Management Tools

Pharmacists found that providing adherence aids was highly valuable for patients with low health literacy, but less so for patients with adequate health literacy. As noted above, pharmacists provided patients with an illustrated medication schedule which facilitated discharge counseling, by clearly depicting the name, indication, dose, frequency, main side effects, and special instructions for each medication. Patients were encouraged to keep the illustrated medication schedule in a visible location at home to promote adherence, and to bring it to doctors’ appointments to facilitate discussion about medications. While pharmacists believed that the illustrated medication schedule was an effective educational tool and reminder for patients, they did note that it was time-consuming to produce. It was made from a template created in a common word processor, and for patients with a long medication list, could take 30–45 minutes to make. This posed a challenge when patients were eager to leave the hospital. Pharmacists also noted that, optimally, a mechanism would exist to create the patient’s illustrated medication schedule more quickly, as well as update it in the future as the medications changed.

Pharmacists also encouraged patients to use the illustrated medication schedule to help them fill a pill box, which was offered to all intervention patients as an adherence aid. The pill box was welcomed by many patients. However, for those patients who were reluctant to use one, pharmacists found it helpful to engage family members’ help during discharge counseling.

Follow-up Call

Pharmacists were generally satisfied with the PILL-CVD model of having non-healthcare professionals conduct the initial post-discharge follow-up calls, which used a scripted interview to identify medication-related issues and any new or worsening symptoms. The study coordinator determined if a follow-up call with a pharmacist was warranted based on whether the patient was experiencing medication-related issues. This model proved relatively efficient for pharmacists, as approximately 60% of patients did not have issues requiring pharmacist involvement, and among those who did, pharmacists could focus on the issue at hand, rather than performing a full review.

Nevertheless, some pharmacists would have preferred to personally conduct the follow-up calls personally, without the intermediate step. Also, while the timing of patient discharge did not always allow the same pharmacist to follow each patient all the way through from admission to discharge and the follow-up call, when continuity was maintained, pharmacists felt that the rapport they had established during the counseling sessions increased the likelihood of patients raising and discussing any medication issues with them during follow-up. They agreed, however, that a pharmacist-led model for post-discharge telephone follow-up in most settings would be time- and cost-prohibitive.

Pharmacists’ Recommendations to Improve Hospital Discharge Procedures

Based on their experience, pharmacists provided a number of suggestions to improve the coordination of care and quality of hospital discharge generally. These recommendations concern multidisciplinary communication, handling of discharge prescriptions, protecting time for discharge counseling, optimizing patient and family engagement in discharge counseling, and the provision of patient education materials (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pharmacists’ recommendations for improving effectiveness in medication reconciliation and the patient discharge processes.

| Suggestion | Comment |

|---|---|

| 1. Integrate pharmacists into the treating team. |

|

| 2. Offer in-hospital filling of discharge prescriptions. |

|

| 3. Communicate about the anticipated date and time of discharge. |

|

| 4. Formally schedule a time for discharge counseling. |

|

| 5. Prepare a draft of patient education materials before discharge. |

|

| 6. Provide patients with a wallet- sized medication list. |

|

| 7. Use illustrations and color coding. |

|

| 8. Offer a mechanism for updating the patient’s personal medication list. |

|

| 9. Teach patients to participate actively in discharge counseling. |

|

| 10. Audio record the discharge counseling session. |

|

| 11. Provide hospital pharmacists with access to pharmacy fill data post-discharge. |

|

| 12. Communicate with primary care physicians at discharge. |

|

Discussion

In this qualitative study of pharmacists who delivered a care transition intervention, we identified strengths and weaknesses of the particular intervention, as well as a number of valuable suggestions to improve the discharge process in general.

All aspects of the PILL-CVD intervention were felt to be valuable, though pharmacists identified medication reconciliation as the most important component and most impactful area for their involvement. Discharge counseling also was a critical time to review medication instructions, focusing on new medications and changes to the patient’s regimen. This counseling was aided by the use of a simple illustrated medication schedule, though it was also challenged by time pressures.

By teaching patients to use medication management tools, pharmacists were involved in promoting patient self-management behaviors. Pharmacists’ varying perceptions of patients’ receptivity to and need for the teach-back suggests the need to customize the teach-back to the patient’s health literacy and medication understanding. For those who understood their medication regimens readily, pharmacists could truncate the teach-back, while for those who needed greater explanation the teach-back could be more thorough.

By participating in the hospital discharge and follow-up of more than 400 patients in the PILL-CVD study, pharmacists developed insights to improve the care transition process in general (Table 1). These included, for example, improving communication about the anticipated time of discharge, scheduling time for discharge counseling, and building rapport with patients so as motivate them and promote their active participation during discharge counseling.

These results are consistent with and add to the lessons learned from other interventions that were designed to improve the transition from hospital to home. In evaluating implementation of the Care Transition Intervention, Coleman and colleagues learned that patients often had poor understanding of their medications at the time of discharge, and suggested greater involvement by hospital clinical staff and pharmacists.23 At the University of Michigan, a pharmacist-facilitated discharge program improved the quality of hospital discharge, largely through the pharmacist’s performance of medication reconciliation, though this was noted to be very time-consuming.24 Project RED at Boston University found that the discharge process was strengthened when planned for in advance and when illustrated patient-centered discharge instructions were used.13

Limitations of this study include its reliance on perspectives of pharmacists from two academic hospitals; it does not represent pharmacists’ views broadly and has limited generalizability. The pharmacists’ comments were based primarily on their experience implementing the PILL-CVD intervention, and did not address other roles that pharmacists may play, such as promotion of guideline-based prescribing or recommending cessation of potentially inappropriate medications.

These limitations notwithstanding, this study enhances understanding of the value of pharmacist-delivered care transition interventions, providing pharmacists’ own insights for improving hospital discharge transitions, and highlighting some of the important roles that pharmacists can play in this process. Notably, pharmacists were involved in cognitively demanding functions that included assessing patients’ understanding and barriers to adherence; building rapport with and motivating patients; and tailoring patient counseling to specific situations and barriers such as low health literacy or cognitive impairment. We hope this hypothesis-generating study will stimulate additional research to better define pharmacists’ optimal role in care transitions, including the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of different approaches, and in different types of settings.

Acknowledgments

Supported by award numbers R01 HL089755, R01 HL089755-02S2, and K23 HL077597 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Appendix A. SEMI-STRUCTURED PHARMACIST INTERVIEW GUIDE

Pharmacist: _____________________________

DATE of Interview:

![]() Start time: __ __: __ __□ AM / □ PM

Start time: __ __: __ __□ AM / □ PM

I. Introduction

Hello, my name is Alison Oberne and I am one of the PILL-CVD Research Coordinators. Thank you for taking the time to speak with me about your experiences with the program.

Before we begin I want to tell you what to expect. I am going to give you a consent form that I will go over, and have you sign. You have two copies: you can sign and turn one in, and keep the second for yourself. By signing this form you give me permission to use the information we discuss today. I will not use your name or personal information in any reports from today’s discussion.

Our discussion should take 45–60 minutes. The only risk for you participating in this interview is that you may be inconvenienced by the time it takes to talk with me. Also, with your permission, I would like to tape-record our conversation. Your name will not be matched with the tape recording. Instead, a code or study ID number will be used. We will keep the tape recording confidential in a locked cabinet so no one outside of the research team will have access to it.

Do I have your permission to record our conversation? □ Yes □ No

Today, I would like to your feedback about experiences with the Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease Patients, also known as the PILL-CVD study. I want to learn about your experiences with the program so we can decrease medication errors among patients. There are no right or wrong answers. You are the expert and I am interested in all that you have to share about this program. Your input will help us understand and improve the intervention.

Your participation in this interview will be confidential. No one outside of the research staff will know you are participating. You can also decide to withdraw at any time. You may choose not to answer a specific question during this interview. Also, if you no longer want to speak with me, just let me know and we can end our interview. My phone number is on the consent form, so contact me if you have any questions afterward.

Do you have any questions? [Yes No] Okay let’s begin.

II. Question Route

First, I’d like you to tell me about your experiences with PILL-CVD program implementation.

-

How receptive were patients to the initial counseling session?

What worked? Can you describe why this is?

What didn’t work? Can you describe/explain why this is?

-

How receptive were patients to the discharge counseling session?

What worked? Can you describe why this is?

What didn’t work? Can you describe/explain why this is?

-

What did you perceive to be the main barriers to safe and effective medication use by patients?

-

Possible examples:

- □ literacy level

- □ lack of social support medications

- □ Other: ____________________

- □ cognition level

- □ lack of funds to purchase

-

Can any of these barriers be overcome?

If so, which? How?

-

-

Did this intervention impact your ability to communicate with patients in your day-to-day work? If so, how?

Have you continued using any techniques from the study?

-

Were you notified of patients’ cognition levels?

If so, how did this process function?

Did you note this information on any paperwork or forms?

-

Did your interactions with patients differ based on their cognition levels? If so, can you describe how?

How helpful was it to be given information about patient’s level of cognition? Did it change your orientation toward the patient? If so, how?

Could you contrast your experience in counseling patients of low vs. high cognition levels?

-

Were you notified of patients’ literacy levels?

If so, how did this process function?

Did you note this information on any paperwork or forms?

-

How did your interactions with patients differ based on literacy levels?

Was it helpful to be given information about patient’s level of health literacy? If so why/why not?

Could you contrast your experience in counseling patients of different literacy levels (inadequate vs. marginal vs. adequate)?

-

Were there any study tools that seemed to be more effective among low literacy patients? If so, which ones? Why?

□ Teach backs □ Illustrated medication schedules

□ Practicing bottle labels □ Pill boxes

Which tools seemed ineffective? Why? Can you describe/provide an example of how they were ineffective?

Which tools were difficult for patients to understand?

Are there other resources that could be used to help you communicate with low literacy patients? If so, what are they?

-

Did you experience any barriers in working with low literacy patients? If so, what are these barriers?

Can these barriers be overcome? If so, how?

Now, I am interested in learning how your time was spent on the intervention tasks.

During initial implementation of an intervention, new users typically experience a learning curve in becoming comfortable with intervention delivery. Can you describe how long it took for you to feel comfortable with delivering the intervention?

-

How did your first few patients differ from the rest of your patients?

How could the learning curve have been decreased?

On what tasks was your time best spent with patients? Can you help me understand why?

Not including documentation you performed for the study, on what tasks was the time you spent with patients least well spent? Why?

-

Are there additional non-study related procedures that you think would most improve patients’ care transitions?

What would you like to see?

Initially the pharmacists completed the counseling forms by paper and then it was changed to entering the information directly into the database. Can you describe for me your preference in this process and how it impacted your ability to counsel patients and track their data?

-

If an intervention similar to PILL-CVD were to become standard operating procedure at this hospital, how could we maximize its value to patients?

How would this type of program be accepted by staff and physicians?

How would this type of program affect efficiency as part of the discharge planning process?

Can you explain to me how you were notified that patients were enrolled in the intervention and how the pharmacists determined who would counsel which patient?

-

Another aspect that impacts the intervention is handovers. Can you help me understand the process for handovers between research staff and pharmacists?

How could this process have been made easier?

Should handovers be addressed in the training? If so, how?

-

As a part of the intervention, the study coordinator called all patients after they returned home from the hospital. The coordinator discussed the medication list and any possible side effects. As a pharmacist, you were then contacted if there were possible adverse drug events.

-

How did this process affect your ability to treat patients?

Probe: Did it help or hinder?

Did this process streamline your telephone conversations with patients?

Would you have preferred to conduct these telephone interviews with all patients?

-

The last issue that I would like to address is the training provided for this intervention.

-

Did you have prior experience in conducting medication reconciliation processes?

If yes, in what context (job, research, etc.)?

Can you please describe/walk me through (sequentially) the training that you received on this intervention? What did it entail?

What other information should have been included in the training?

Was there any information in the training that you could have done without?

Is there anything else you would like to share today to round out your perspective?

III. Conclusion

“Thank you for speaking with me today. Please let me know if you have any questions about our conversation.”

Project Coordinator: __________________ End time: __ __: __ __ □ AM / □ PM

Appendix Figure.

Example of an illustrated medication schedule (reduced in size).

Footnotes

Katherine Taylor Haynes has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Alison Oberne has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Courtney Cawthon has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

A poster of this paper was presented at the 34th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine:

Haynes K Taylor, Oberne A, Cawthon C, Schnipper JL, Kripalani S. (2011, May) Pharmacists’ Perspectives on a Pharmacist-led Care Transitions Intervention: What Can We Learn from PILL-CVD? Poster presented at the Society for General Internal Medicine annual meeting, Phoenix, AZ.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Kripalani is a consultant to and holds equity in PictureRx, LLC. The terms of this agreement were reviewed and approved by Vanderbilt University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. PictureRx provided no materials or funding for this study.

Contributor Information

Katherine Taylor Haynes, Email: katherine.taylor.haynes@vanderbilt.edu, Dept. of Leadership, Policy and Organizations, Peabody College of Education and Human Development, Vanderbilt University, PMB #414, 230 Appleton Place, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37203-5721, Tel: 615 343-4327, Fax: 615 322-7890.

Alison Oberne, Email: aoberne@health.usf.edu, College of Public Health, University of South Florida, Office: Student & Academic Affairs, COPH 1130, Mail: 13201 Bruce B. Downs Blvd., MDC 56, Tampa, FL 33612, 813-974-4246.

Courtney Cawthon, Email: courtney.cawthon@vanderbilt.edu, Vanderbilt Center for Health Services Research, Vanderbilt University, 1215 21st Ave S, Suite 6000 Medical Center East, Nashville, TN 37232, 615-936-1785, 615-936-1269 (fax).

Sunil Kripalani, Email: sunil.kripalani@vanderbilt.edu, Section of Hospital Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine and Public Health, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University, 1215 21st Ave S, Suite 6000 Medical Center East, Nashville, TN 37232, 615-936-3525, 615-936-1269 (fax).

References

- 1.DeFrances CJ, Lucas CA, Buie VC, Golosinskiy A. 2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:314–323. doi: 10.1002/jhm.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cua YM, Kripalani S. Medication use in the transition from hospital to home. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:136–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:317–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.30390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kripalani S, Henderson LE, Jacobson TA, Vaccarino V. Medication use among inner-city patients after hospital discharge: patient reported barriers and solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:529–535. doi: 10.4065/83.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min SJ. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1842–1847. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.16.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161–167. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. [Accessed Jan 13, 2012];Medication reconciliation. Available at http://www.ihi.org/explore/adesmedicationreconciliation/Pages/default.aspx.

- 11.Joint Commission. [Accessed Jan 13, 2012];Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goals. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/

- 12.Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, Schnipper JL. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:955–964. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:178–187. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnipper JL, Hamann C, Ndumele CD, et al. Effect of an electronic medication reconciliation application and process redesign on potential adverse drug events: a cluster-randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:771–780. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:565–571. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnipper JL, Roumie CL, Cawthon C, et al. The rationale and design of the Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease (PILL-CVD) study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:212–219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.921833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nurss JR, Parker RM, Williams MV, Baker DW. Short test of functional health literacy in adults. Snow Camp, NC: Peppercorn Books and Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J, Tu SP, Lessig M. Simplifying detection of cognitive impairment: comparison of the Mini-Cog and Mini-Mental State Examination in a multiethnic sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:871–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kripalani S, Jacobson KL. AHRQ publication No 07(08)-0051-1-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Oct, 2007. Strategies to improve communication between pharmacy staff and patients. A training program for pharmacy staff. (Curriculum guide prepared under contract No. 290-00-0011 T07.) Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/pharmlit/pharmtrain.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NVivo Qualitative data analysis. Melbourne, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kripalani S, Robertson R, Love-Ghaffari MH, et al. Development of an illustrated medication schedule as a low-literacy patient education tool. Patient Ed Counsel. 2007;66:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parrish MM, O’Malley K, Adams RI, Adams SR, Coleman EA. Implementation of the care transitions intervention: sustainability and lessons learned. Prof Case Manag. 2009;14:282–293. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e3181c3d380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker PC, Bernstein SJ, Jones JNT, et al. Impact of a pharmacist-facilitated hospital discharge program: a quasi-experimental study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2003–2010. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]