Abstract

Background

Patients’ ability to accurately report their pre-admission medications is a vital aspect of medication reconciliation and may affect subsequent medication adherence and safety. Little is known about predictors of pre-admission medication understanding.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional evaluation of patients at 2 hospitals using a novel Medication Understanding Questionnaire (MUQ). MUQ scores range from 0 to 3 and test knowledge of the medication purpose, dose, and frequency. We used multivariable ordinal regression to determine predictors of higher MUQ scores.

Results

Among the 790 eligible patients, the median age was 61 (interquartile range [IQR] 52, 71), 21% had marginal or inadequate health literacy, and the median number of medications was 8 (IQR 5, 11). Median MUQ score was 2.5 (IQR 2.2, 2.8). Patients with marginal or inadequate health literacy had a lower odds of understanding their medications (odds ratio [OR]=0.53; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34 to 0.84; p=0.0001; and OR=0.49; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.78; p=0.0001; respectively), compared to patients with adequate health literacy. Higher number of prescription medications was associated with lower MUQ scores (OR=0.52; 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.75; for those using 6 medications vs 1; p=0.0019), as was impaired cognitive function (OR=0.57; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.86; p=0.001).

Conclusions

Lower health literacy, lower cognitive function, and higher number of medications each were independently associated with less understanding of the pre-admission medication regimen. Clinicians should be aware of these factors when considering the accuracy of patient-reported medication regimens and counseling patients about safe and effective medication use.

Keywords: Health Literacy, Medication Reconciliation

INTRODUCTION

With the aging of the U.S. population, complex medication regimens to treat multiple comorbidities are increasingly common.1 Nevertheless, patients often do not fully understand the instructions for safe and effective medication use. Aspects of medication understanding include knowledge of the drug indication, dose, frequency, and for certain medications, special instructions.2 Medication understanding is associated with better medication adherence, fewer drug-related problems, and fewer emergency department visits.3 Among patients with chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), understanding and adherence to the medication regimen are critical for successful disease control and clinical outcomes.4

Patients’ understanding of their medication regimen is also vitally important upon admission to the hospital. Patients often are the main source of information for the admission medication history and subsequent medication reconciliation.5 Poor patient understanding of the pre-admission medication regimen can contribute to errors in inpatient and post-discharge medication orders and adversely affect patient safety.6 However, little research has examined patients’ understanding of the pre-admission medication regimen and factors that affect it.

In the outpatient setting, previous investigations have suggested that low health literacy, advanced age, and impaired cognitive function adversely affect patients’ understanding of medication instructions.2, 7-8 These studies were limited by a small sample size, single site, or focus on a specific population, such as inner-city patients. Additionally, the measures used to assess medication understanding were time-consuming and required patients’ medications to be present for testing, thus limiting their utility.2

To address these gaps in the literature, we developed and implemented the Medication Understanding Questionnaire (MUQ), an original and relatively rapid measure that does not require patients’ medications be present for testing. In a study of adults at 2 large teaching hospitals, we examined the association of health literacy, age, cognitive function, number of pre-admission medications, and other factors on patients’ understanding of their pre-admission medication regimen. We hypothesized that lower health literacy would be independently associated with lower medication understanding as assessed using the MUQ.

METHODS

The present study was a cross sectional assessment conducted using baseline interview data from the Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease (PILL-CVD) Study. The PILL-CVD Study is a randomized controlled trial of a pharmacist-based intervention, consisting of pharmacist-assisted medication reconciliation, inpatient counseling, low-literacy adherence aids, and post-discharge telephone follow-up. It was conducted at 2 academic medical centers – Vanderbilt University Hospital (VUH) in Nashville, TN, and Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) in Boston, MA.9 This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Population

The PILL-CVD study protocol and eligibility criteria has been previously published.9 Briefly, patients were eligible if they were at least 18 years old and admitted with acute coronary syndrome or acute decompensated heart failure. Patients were excluded if they were too ill to complete an interview; were not oriented to person, place, or time; had a corrected visual acuity worse than 20/200; impaired hearing; could not communicate in English or Spanish; were not responsible for managing their own medications; had no phone; were unlikely to be discharged to home; in police custody; or had been previously enrolled in the study. For the present analysis, we also excluded any patient who was not on at least 1 prescription medication prior to admission. Saline nasal spray, saline eye drops, herbal products, nutritional supplements, vitamins, and over the counter (OTC) lotions and creams were not counted as prescription medications. Oral medications available both OTC and by prescription (e.g., aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and acid reflux medications) were counted as prescription medications.

Measures

At enrollment, which was usually within 24-48 hours of admission, participants completed the short form of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (s-TOFHLA) in English or Spanish,10 the Mini-Cog test of cognition,11 and the Medication Understanding Questionnaire (MUQ), as well as demographic information. The number of prescription medications prior to hospital admission was abstracted from the best available reference list – that documented by the treating physicians in the electronic health record (EHR). The EHR at each site was a “home-grown” system and included both inpatient and outpatient records, which facilitated physicians’ documentation of the medication list.

The s-TOFHLA consists of 2 short reading comprehension passages. Scores on the s-TOFHLA range from 0 to 36 and can be categorized as inadequate (0-16), marginal (17-22), or adequate (23-36) health literacy.10 The Mini-Cog includes a 3-item recall and clock drawing test. It provides a brief measure of cognitive function and performs well among patients with limited literacy or educational attainment.11 Scores range from 0 to 5, with a score < 3 indicating possible dementia.

The MUQ was administered verbally and assessed patients’ understanding of their own pre-admission medication regimen. It was developed for this study, based on published measures of medication understanding.2, 12 To administer the MUQ, research assistants (RAs) accessed the patient's pre-admission medication list from the electronic health record (EHR) and used a random number table to select up to 5 prescription medications from the list. If the patient was taking 5 or fewer medications, all of their medications were selected. Saline nasal spray, saline eye drops, herbal products, nutritional supplements, vitamins, and OTC lotions and creams were excluded from testing. The RA provided the brand and generic name of each medication, and then asked the patient for the drug's purpose, strength per unit (e.g., 20 mg tablet), number of units taken at a time (e.g., 2 tablets), and dosing frequency (e.g., twice a day). For drugs prescribed on an as-needed basis, the RA asked patients for the maximum allowable dose and frequency. Patients were instructed to not refer a medication list or bottles when responding. The RA documented the patient's responses on the MUQ along with the dosing information from the EHR for each selected medication.

One clinical pharmacist (MM) scored all MUQ forms by applying a set of scoring rules. Each medication score could range from 0 to 3. The components of the score included indication (1 point), strength (0.5 point), units (0.5 point), and frequency (1 point). The patient's overall MUQ score was an average of the MUQ scores for each tested medication.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized patient characteristics, number of pre-admission medications, and MUQ scores using median and interquartile range (IRQ) for continuous variables, and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. We conducted proportional odds logistic regression (ordinal regression) to estimate the effect of s-TOFHLA score, other patient characteristics, and number of medications on MUQ scores.13

Important covariates were selected a priori based on clinical significance. These included age (continuous), gender, patient self-reported race (white, black, other nonwhite), mini-Cog score (continuous), primary language (English or Spanish), years of education (continuous), number of pre-admission medications (continuous), income (ordinal categories), insurance type (categorical), and study site. Covariates with missing data (household income, health literacy, and years of education) were imputed using multiple imputation techniques.14 The relationship between number of pre-admission medications and MUQ scores was found to be non-linear, and it was modeled using restricted cubic splines.14 We also fit models which treated health literacy and cognition as categorical variables. Results are reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Wald tests were used to test for the statistical significance of predictor variables. Two-sided p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using statistical language R (R Foundation, available at: http://www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Among the 862 patients enrolled in PILL-CVD, 790 (91.7 %) had at least 1 pre-admission medication and were included in this analysis (Table 1). Forty seven percent were admitted to VUH (N=373) and 53% to BWH (N=417). The median age was 61 (IQR 52, 71), 77% were white, and 57% were male. Inadequate or marginal health literacy was identified among 11% and 9% of patients, respectively. The median number of pre-admission medications was 8 (IQR 5, 11). Patients excluded from the analysis for not having pre-admission medications were similar to included patients, except they were more likely to be male (76% vs. 57%) and less likely to have health insurance (23% self-pay vs. 4%). (Data available upon request.)

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic | N=790 |

|---|---|

| Study Hospital, N (%) | |

| Vanderbilt University Hospital | 373 (47.2) |

| Brigham and Women's Hospital | 417 (52.8) |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 61 (52, 71) |

| Gender, N (%) | |

| Male | 452 (57.2) |

| Female | 338 (42.8) |

| Primary language, N (%) | |

| English | 779 (98.6) |

| Spanish | 11 (1.4) |

| Race, N (%) | |

| White | 610 (77.2) |

| Black or African American | 136 (17.2) |

| Other | 44 (5.6) |

| Health Literacy, s-TOFHLA score, median (IQR) | 33 (25,35) |

| Health Literacy, N (%)* | |

| Inadequate | 84 (10.6) |

| Marginal | 74 (9.4) |

| Adequate | 613 (77.6) |

| Mini Cog score, median (IQR) | 4 (3, 5) |

| Dementia, N (%) | |

| No | 692 (87.6) |

| Yes | 98 (12.4) |

| Number of medications, median (IQR) | 8 (5, 11) |

| Health insurance type, N (%) | |

| Medicaid | 74 (9.4) |

| Medicare | 337 (42.6) |

| Private | 334 (42.3) |

| Self-pay | 35 (4.4) |

| Other | 10 (1.3) |

| Self-reported household income, N (%)* | |

| <$10,000 | 38 (4.8) |

| $10,000 to < $15,000 | 45 (5.7) |

| $15,000 to < $20,000 | 42 (5.3) |

| $20,000 to < $25,000 | 105 (13.3) |

| $25,000 to < $35,000 | 99 (12.5) |

| $35,000 to < $50,000 | 112 (14.2) |

| $50,000 to < $75,000 | 118 (14.9) |

| $75,000+ | 227 (28.7) |

| Years of school, median (IQR)* | 14 (12, 16) |

Missing sTOFHLA N=19; missing household income N=4; missing years of school N= 1

MUQ Scores

The MUQ was administered in approximately 5 minutes. The median MUQ score was 2.5 (IQR 2.2, 2.8) (Table 2); 16.3% of patients scored less than 2. Subjects typically achieved high scores for the domains of indication, units, and frequency, while scores on the strength domain were lower (median=0.2 [IQR 0.1, 0.4], maximum possible=0.5).

Table 2.

MUQ scores and components at baseline among 790 patients using at least 1 medication

| Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|

| Number of drugs tested | 5 (4, 5) |

| Medication Understanding Questionnaire score* | 2.5 (2.2, 2.8) |

| Indication | 1.0 (0.8, 1.0) |

| Strength | 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) |

| Units | 0.5 (0.4, 0.5) |

| Frequency | 1.0 (0.8, 1.0) |

Each medication score could range from 0 to 3. For each medication tested, the components of the score included indication (1 point), strength (0.5 point), units (0.5 point), and frequency (1 point). The patient's overall MUQ score was then the average of the MUQ scores for each medication.

Predictors of Medication Understanding

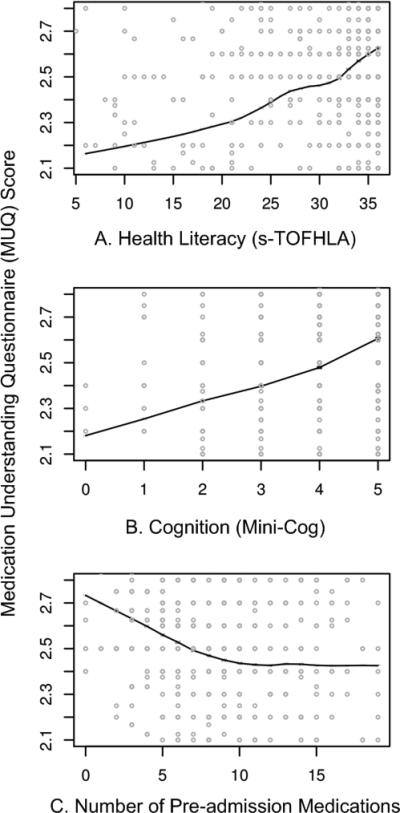

Unadjusted relationships of health literacy, cognition, and number of medications with medication understanding are shown in Figure 1 (panels A, B, and C, respectively). The figure demonstrates a linear relationship with both health literacy (Figure 1A) and cognition (Figure 1B), and a non-linear relationship between number of pre-admission medications and MUQ score (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted relationships of MUQ scores with health literacy (panel A), cognition (panel B) and number of pre-admission medications (panel C).

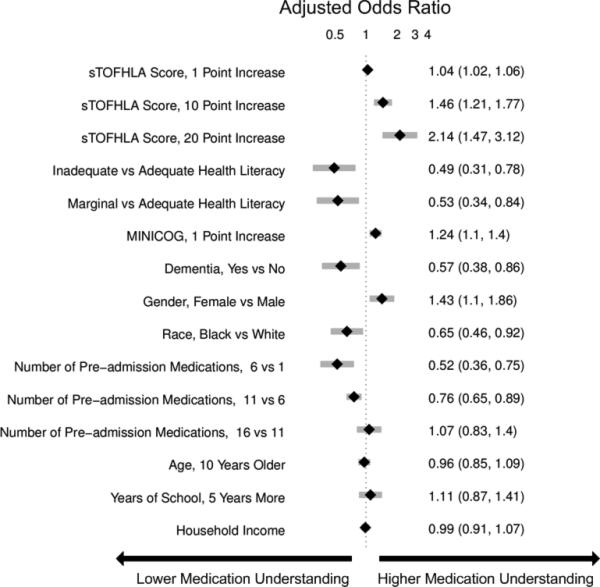

Adjusted relationships using imputed data for missing covariates are shown in Figure 2. Lower health literacy, cognitive impairment, male gender, and black race were independently associated with lower understanding of pre-admission medications. Each 1 point increase in s-TOFHLA or Mini-Cog score led to an increase in medication understanding ([OR=1.04; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.06; p=0.0001], [OR=1.24; 95% CI, 1.1 to 1.4; p=0.001], respectively). Patients with marginal or inadequate health literacy had lower odds of understanding their regimen ([OR=0.53; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.84], [OR=0.49; 95% CI, 0.31, 0.78], respectively) compared to those with adequate health literacy. Impaired cognitive function (Mini-Cog score < 3, indicating dementia) was also associated with lower odds of medication understanding (OR=0.57; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.86) compared to those with no cognitive impairment. An increase in the number of pre-admission medications (up to 10) was also strongly associated with lower MUQ scores. For each increase by 1 medication there was a significant decrease in medication understanding, up to 10 medications, beyond which understanding did not significantly decrease further. Patients on 6 medications were about half as likely to understand their medication regimen as patients on only 1 medication (OR=0.52; 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.75). For patients on 11 medications, the odds of medication understanding were 24% lower than for patients on 6 medications (OR=0.76; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.89). Patients’ age, years of schooling, and household income were not independently associated with medication understanding. Results were similar using data without multiple imputation.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the adjusted odds of a higher MUQ score compared to an average patient. *Odds Ratios (OR) of less than 1 represent lower medication understanding. OR of greater than 1 represent higher medication understanding. Model includes: age, gender, patient self reported race, s-TOFHLA score, cognitive function, primary language, years of education, number of pre-admission medications (non linear restricted cubic spline with 3 knots), income, insurance type, and study site. Diamonds represent point estimate and shaded gray bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Examples of Misunderstanding of Common Medications

Table 3 provides examples of incorrect patient responses for several commonly prescribed medications or drug classes, including aspirin, digoxin, nitroglycerin, and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins). For aspirin, many patients were not aware of the strength. For digoxin, several participants reported splitting a higher-strength pill to obtain the prescribed dose, which should not be done given the imprecision of splitting and narrow therapeutic index of this drug. Patients prescribed nitroglycerin sublingual tablets were commonly unable to report the correct dosing and frequency for angina treatment. Medications for cholesterol were often reported as being taken in the morning; this was scored strictly as a frequency error if the medication timing in the EHR was listed as evening or bedtime. We also identified many patients with poor understanding of opioid analgesics, particularly regarding their dosing and frequency.

Table 3.

Common Incorrect responses for frequent medications and resulting error code on MUQ

| Medications | Common incorrect responses | Correct information | Coded error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | ½ tablet twice a day | 1 tablet once a day | Units and Frequency |

| I am not aware what aspirin I am taking | 81 mg once a day | Strength | |

| I am taking 6-something every day | 81 mg once a day | Strength | |

| 31 mg a day | 81 mg once a day | Strength | |

| 180 mg a day | 81 mg once a day | Strength | |

| 1 low dose daily | 325 mg once a day | Strength | |

| 125 mg a day | 325 mg once a day | Strength | |

| I am taking it for my blood pressure | Heart medication | Indication | |

| Nitroglycerin sublingual | As needed, I have taken up to 4 a day | Dissolve 1 tablet under the tongue, every 5 minutes as needed, up to 3 doses. | Frequency |

| As needed every 15 minutes | Frequency | ||

| As needed up to 4 doses every 10 minutes | Frequency | ||

| Dissolve couple units under the tongue, as needed | Units and Frequency | ||

| As many as I want, every 5 minutes | Frequency | ||

| Digoxin | ½ tablet daily | 1 tablet daily | Units |

| 1 tablet daily | 1 tablet every other day | Frequency | |

| I am taking it for my blood pressure | Heart medication | Indication | |

| HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors | 1 tablet every morning | 1 tablet every evening | Frequency |

| ½ tablet twice a day | 1 tablet once a day | Units and Frequency | |

| I do not know the indication | High cholesterol | Indication | |

| Propoxyphene/acetaminophen | ½ tablet as needed | 1 tablet every 4-6h as needed | Units and Frequency |

| Hydrocodone/acetaminophen | I do not know the strength of this medication | 5mg/500mg | Strength |

| 1 tablet as I need it | 1 tablet every 4-6h as needed | Frequency | |

DISCUSSION

We used a novel four-component medication understanding questionnaire, developed for this study, to assess patients’ understanding of up to 5 drugs selected randomly from the participant's pre-admission medication list. The MUQ proved to be easy to administer by non-medical staff within a short period of time (approximately 5 minutes per patient). It was well understood by patients. By limiting the assessment to 5 or fewer medications, the MUQ has a distinct advantage over existing measures of medication understanding that require testing the entire regimen. We did not find any limitations related to cutting off the assessment at 5 medications. In addition, this tool affords assessment of medication understanding without requiring medication bottles be present, enhancing its utility in the inpatient setting.

MUQ scores were associated with health literacy and other patient characteristics in an expected manner. We demonstrated that inadequate or marginal health literacy, as well as impaired cognitive function, were associated with low medication understanding. We also were able to demonstrate a relationship between increasing number of medications and lower medication understanding. Interestingly, in our patient population understanding continued to decrease until reaching 10 medications, beyond which further increases in the number of medications had no additional detrimental effect on medication understanding. This non-linear relationship between number of medications and medication understanding has potential implications for prescribing practice.

Our findings which utilize the MUQ among inpatients are consistent with prior literature in other settings.2, 7-8 In a previous outpatient study, we identified that health literacy plays an important role in a patient's ability to successfully report and manage their daily medications.2 Other studies have also shown that patients with low health literacy have more difficulty understanding prescription drug information, and that they often experience medication-related problems after hospital discharge.15-16 The number and often the types of medications an individual takes have also been shown to increase the risk for adverse events and non-adherence to the treatment plan.17-20 We postulate that this risk of adverse drug events is related at least in part to a patient's understanding of their medication regimen.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the MUQ did not assess certain aspects of medication understanding such as knowledge of pill appearance or side effects. Nor did it assess components of patients’ actual drug-taking behavior such as organization of medications or behavioral cues. Thus, adaptive behaviors that patients may perform to improve their medication management, such as writing on labels or memory cues, are not captured by this test. Second, in administering and scoring the MUQ, we used the patient's pre-admission medication list documented in the EHR as the reference standard. This was the best available reference list, and was generally accurate, as both hospitals had medication reconciliation systems in use at the time of the study.21 Nevertheless it may contain inaccuracies. Documentation for certain medications, such as warfarin, in which dose can change frequently, often did not reflect the latest prescribed dose. In such cases, we scored the patient's answer as correct if the dose appeared reasonable and appropriate to the clinical pharmacist. As a result a patient's MUQ score may have been overestimated in these cases.

Additional research will be needed to further validate the MUQ in other settings. In particular, studies should establish the relationship between the MUQ, serious medication errors after discharge, and potential to benefit from educational interventions. Also, as noted above, the non-linear relationship between number of medications and medication understanding should be confirmed in other studies.

In conclusion we demonstrated that patients with low health literacy, impaired cognition, or a higher number of medications had significantly poorer understanding of their pre-admission medication regimen. These findings have important clinical implications. It would be appropriate to exercise greater caution when taking a medication history from patients who cannot readily provide the purpose, strength, units, and frequency of their medications. Attempts to validate the information obtained from patients with other sources of data, such as family members, inpatient or outpatient health records, and community pharmacy records should be considered. Patients at high risk for poor medication understanding, either measured directly using the MUQ or identified via risk factors such as polypharmacy, low cognition, or low health literacy, may warrant more intensive medication reconciliation interventions and/or educational counseling and follow-up to prevent post-discharge adverse drug events. Further research is needed to determine if targeting these populations for interventions improves medication safety during transitions in care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funded by R01 HL089755 (NHLBI, Kripalani) and also by K23 HL077597 (NHLBI, Kripalani), K08 HL072806 (NHLBI, Schnipper), and VA Career Development Award 04-342-2 (Roumie). The funding sources did not participate in the planning, collection, analysis or interpretation of data or in the decision to submit for publication. The investigators had full access to the data and were responsible for the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, progress of the study, analysis, reporting of the study and the decision to publish.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

All authors declare no conflicts of interest, except Dr. Kripalani is a consultant to and holds equity in PictureRx, LLC. The terms of this agreement were reviewed and approved by Vanderbilt University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. PictureRx had no role in the design or funding of this study.

All authors had access to the data and a role in writing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2269–2276. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kripalani S, Henderson LE, Chiu EY, Robertson R, Kolm P, Jacobson TA. Predictors of medication self-management skill in a low-literacy population. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):852–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(23):3028–3035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1414–1422. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0687-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsilimingras D, Bates DW. Addressing postdischarge adverse events: a neglected area. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(2):85–97. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edelberg HK, Shallenberger E, Wei JY. Medication management capacity in highly functioning community-living older adults: detection of early deficits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(5):592–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiers MV, Kutzik DM, Lamar M. Variation in medication understanding among the elderly. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2004;61(4):373–380. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schnipper JL, Roumie CL, Cawthon C, et al. The rationale and design of the Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease (PILL-CVD) study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:212–219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.921833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nurss JR, Parker RM, Williams MV, Baker DW. Short test of functional health literacy in adults. Peppercorn Books and Press; Snow Camp, NC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J, Tu SP, Lessig M. Simplifying detection of cognitive impairment: comparison of the Mini-Cog and Mini-Mental State Examination in a multiethnic sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):871–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farris KB, Phillips BB. Instruments assessing capacity to manage medications. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(7):1026–1036. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker SH, Duncan DB. Estimation of the probability of an event as a function of several independent variables. Biometrika. 1967;54(1):167–179. Jun. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrell FE, Jr., Shih YC. Using full probability models to compute probabilities of actual interest to decision makers. International journal of technology assessment in health care. 2001;17(1):17–26. doi: 10.1017/s0266462301104034. Winter. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, III, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):887–894. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kripalani S, Henderson LE, Jacobson TA, Vaccarino V. Medication use among inner-city patients after hospital discharge: patient reported barriers and solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(5):529–535. doi: 10.4065/83.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Budnitz DS, Pollock DA, Weidenbach KN, Mendelsohn AB, Schroeder TJ, Annest JL. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA. 2006;296(15):1858–1866. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Budnitz DS, Shehab N, Kegler SR, Richards CL. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(11):755–765. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:317–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.30390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gandhi TK, Weingart SN, Borus J, et al. Adverse drug events in ambulatory care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1556–1564. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnipper JL, Hamann C, Ndumele CD, et al. Effect of an electronic medication reconciliation application and process redesign on potential adverse drug events: a cluster-randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(8):771–780. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]