Abstract

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) and regulatory T (Treg) cells are major components of the immune suppressive tumour microenvironment (TME). Both cell types expand systematically in preclinical tumour models and promote T-cell dysfunction that in turn favours tumour progression. Clinical reports show a positive correlation between elevated levels of both suppressors and tumour burden. Recent studies further revealed that MDSCs can modulate the de novo development and induction of Treg cells. The overlapping target cell population of Treg cells and MDSCs is indicative for the importance and flexibility of immune suppression under pathological conditions. It also suggests the existence of common pathways that can be used for clinical interventions aiming to manipulate the TME. Elimination or reprogramming of the immune suppressive TME is one of the major current challenges in immunotherapy of cancer. Interestingly, recent findings suggest that natural killer T (NKT) cells can acquire the ability to convert immunosuppressive MDSCs into immunity-promoting antigen-presenting cells. Here we will review the cross-talk between MDSCs and other immune cells, focusing on Treg cells and NKT cells. We will consider its impact on basic and applied cancer research and discuss how targeting MDSCs may pave the way for future immunocombination therapies.

Keywords: immunocombination therapy, myeloid-derived suppressor cell, natural killer T cell, regulatory T cell, tumour microenvironment

Introduction

Immunotherapy is a promising treatment modality for many different types of cancer.1 Several tumour-associated antigens recognized by specific monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and T cells have been identified, providing essential tools for the development of immunotherapies, including dendritic cell (DC) -based vaccination and adoptive T-cell transfer. Sipuleucel-T is the first US Food and Drug Administration-approved vaccine immunotherapeutic for prostate cancer, consisting of an autologous DC-enriched fraction loaded with tumour antigen.2 Such studies stimulate the entire field to sustain current efforts for identifying the optimal antigen-presenting cell (APC), antigens, format, dose, route and adjuvants.3,4 The presence of vaccine-induced immune effector cells with anti-tumour reactivity, however, does not always correlate with clinical benefit. Indeed, many different local and systemic mechanisms and regulatory pathways exist that can antagonize cancer-directed immune responses.5 Tumours have evolved mechanisms to create an immunosuppressive network enriched for soluble mediators, receptors and cells that negatively influence immunotherapy (Fig 1).5 Although tumour-infiltrating T cells (TIL) are present in many cancers, often their lytic machinery is impaired or they are unable to effectively attack tumour cells. This is a result of the presence of co-inhibitory molecules or the down-regulation of either tumour antigens or MHC.6 As the absolute reduction of MHC class I (MHCI) would favour tumour recognition by natural killer (NK) cells,7 tumours adjust MCH levels as well as the expression of NK receptors to minimize TIL and NK cell recognition.6–8 Furthermore, proper effector functions of effector T (Teff) cells are counteracted by immunosuppressive lymphocytes. CD4+ CD25hi FoxP+ Treg cells,9,10 CD8+ CD25+ Treg cells,11 CD19+ CD25hi regulatory B cells12 and interleukin-13 (IL-13) -producing NKT cells13 have all been documented in the tumour microenvironment (TME) of pre-clinical models and in cancer patients. Additionally, the TME conditions the local myeloid cells to become immunosuppressive, as evidenced by the presence of Tie2-expressing monocytes,14 tolerogenic DC,15 tumour-associated macrophages (TAM) and tumour-associated neutrophils (TAN).16,17 More recently, another prominent effect of growing tumours has been elucidated: the aberrant activation of myelopoiesis resulting in the expansion and recruitment of immature myeloid cells.18,19 During the early phase of infection, trauma or stress these immature myeloid cells are believed to play an important role in replenishing DC, macrophages or neutrophils, whereas in the later phase they can prevent immune pathology.18 In tumour-bearing patients this development process appears to be defective and results in the accumulation and retention of highly immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC).19 Their proliferation, aberrant activation and persistence is induced by chronic inflammation in the TME.20 They are further characterized by the continuous production of inflammatory mediators, including IL-1, IL-6, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO).18,19 Furthermore the cells and factors present in the tumour create a microenvironment that is characterized by hypoxia, lactic acid build-up and adenosine accumulation, which in sum prevents APC maturation.5,19,21 Hence, the TME is highly effective in counteracting the tumoricidal function of activated immune effector cells attempting to eradicate the tumour. In this review we will focus on the immunosuppressive function of MDSC and their cross-talk with Treg cells and NKT cells. Furthermore, we will discuss new developments that could potentially be used to reprogramme the hostile TME into an immune potentiating environment.

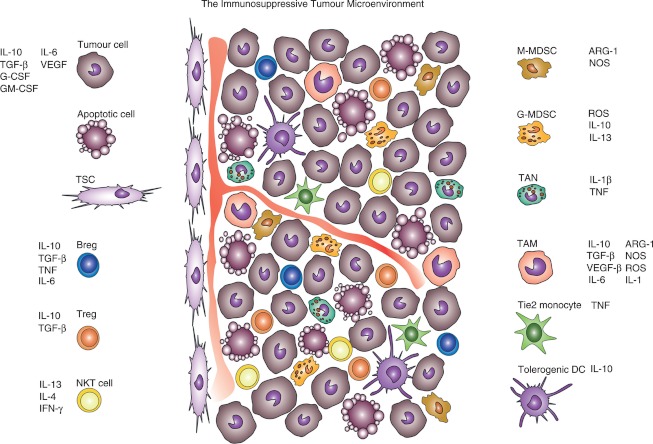

Figure 1.

In the tumour network, several different immune and non-immune cells respond to tumour stimuli and exhibit complex regulatory or immunosuppressive functions, either in a cell–cell contact-dependent manner or through the secretion of soluble mediators. ARG-1, arginase-1; Breg, regulatory B cell; DC, dendritic cell; G-MDSC and M-MDSC, granulocytic and myeloid-derived suppressor cells; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; NKT cells, natural killer T cells; NOS, nitric oxide species; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TAM, tumour-associated macrophage; TAN, tumour-associated neutrophil; TGF, transforming growth factor; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; Treg, regulatory T cell; TSC, tumour stromal cell; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

The MDSC consist of immature myeloid cells and have a bewildering diversity of phenotypes, which provides both opportunities and frustrations for scientists. In tumour-bearing mice two main MDSC subtypes have been reported, granulocytic (G-MDSC) and monocytic (M-MDSC). The G-MDSC are defined by the combinatory expression of CD11b+ Gr-1hi Ly-6G+ Ly-6Clo CD49d−, whereas the M-MDSC are characterized by the phenotype CD11b+ Gr-1hi Ly-6G− Ly-6Chi CD49d+.19 In humans the situation is even more complex (Table 1), but M-MDSC are predominantly CD14+ and G-MDSC are CD15+, both being CD33+ HLA-DR−.22–28 In both mice and humans the G-MDSC represent the major subset of circulating and expanding MDSC.19 Almost all patients and animal models with cancer reveal approximately 75% G-MDSC compared with approximately 25% M-MDSC.25,29–31 Increased production of intra-tumoral granulocyte (G-CSF) or granulocyte–macrophage (GM-CSF) colony-stimulating factors may account for the difference seen in G-MDSC and M-MDSC levels.20,32 Inappropriate levels of G-CSF have been reported for many different human tumours, including pancreatic, oesophageal, gastric and glioma.33,34 Waight et al.35 identified tumour-derived G-CSF as a key driver of G-MDSC accumulation in mice. The relative abundance of the G-MDSC does, however, not necessarily mean that they are more important for suppression as M-MDSC have been proposed to be more immunosuppressive than G-MDSC on a per cell basis.30,32,36 It has been previously proposed that MDSC entering the TME can differentiate into TAM or TAN in mice.16,17,19,21,37 However, as no definitive marker set has been established, it remains difficult to discriminate whether TAN are G-MDSC recruited from the spleen or the bone marrow, or rather represent mature neutrophils polarized to a pro-tumorigenic N2 phenotype through high intra-tumoral concentrations of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β).17 New transcriptomic data by Fridlender et al.37 revealed that the expression signature of blood-derived neutrophils and CD11b+ Ly-6G+ G-MDSC in mice is more closely related to each other than to the TAN. Many immune-related genes such as MHC II, tumour necrosis factor and IL-1 were highly expressed in G-MDSC, and further up-regulated in TAN compared with neutrophils. Angiogenic factors, matrix-degrading enzymes and genes related to cell cytoxicity, including ROS production, were down-regulated in TAN compared with neutrophils.37 In parallel, Ly-6Chi CX3CR1hi monocytes have been proposed as precursors of two, molecularly and functionally distinct Ly-6Cint TAM subsets in three different tumour models.38 Of these, MHCIIlo TAM were enriched in hypoxic regions of the TME and showed a superior pro-angiogenic activity in vivo, whereas MHCIIhi TAM were mainly normoxic, but both subsets equally efficiently suppressed Teff cells.38 Indeed, hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α within the TME seem to be responsible for the up-regulation of arginase-1 (ARG-1) and NOS in CD11b+ Gr-1+ MDSC and their differentiation into TAM.21 Collectively, these findings indicate that myeloid cells may have the plasticity to interconvert between different phenotypes, and that the TME can have a major effect on their phenotype and function.16,19 However, the exact nature of the combination of tumour-derived factors that induce the mobilization and abnormal activation and expansion of MDSC is far from complete. Therefore, direct ex vivo studies are important but are limited because human MDSC appear to rapidly lose their suppressive capacity after cryopreservation.39 Especially the conditions determining the differences in MDSC phenotypes, how they are affected by intra-tumoral inflammation and the presence of TIL should ultimately be answered using sophisticated in vivo strategies. The definition of specific markers for MDSC subsets, especially in humans, remains another important issue. So far, expression of the transcription factor CCAAT enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ) in mouse G-MDSC and M-MDSC,40 and the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) -mediated up-regulation of the myeloid-related protein S100A9 on human CD14+ HLA-DR−/lo M-MDSC41 have been proposed. Although these results provide important clues, it is still an open question how these molecular MDSC markers relate to their suppressive function, and whether they are common to MDSC from different tumours. The most definitive identification of MDSC still remains their immunosuppressive function.

Table 1.

Phenotypes used to characterise MDSCs in human tumors

| MDSC phenotype | MDSC data | Cancer type | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD11b+ CD33+ HLA-DR− Lin−/lo | Circulating MDSC levels correlated with cancer stage and chemotherapy sensitivity | Breast cancer | 97 |

| CD124+ CD14+ CD124+ CD15+ | IL-4Rα expression correlated with immunosuppressive activity | Colon carcinoma | 22 |

| CD14+ HLA-DR−/lo S100A9+ | TLR4L/IFN-γ stimulation induced NO synthase 2 | Colon carcinoma | 41 |

| CD14+ HLA-DR−/lo | ARG-1+ MDSC suppressed autologous T cells and NK cells, induced Treg cells in vitro | Hepatocellular | 50 |

| CD14+ HLA-DR−/lo Stathi CD80+ CD83+ DC-Sign+ | Stathi MDSC produce ARG-1 to suppress T cells, failed to induce Treg cells in vitro | Melanoma | 27 |

| CD14+ HLA-DR−/lo | Increased levels of MDSC and Treg cells, decreased levels of DC | Melanoma | 96 |

| CD33+ Lin− HLA-DR− | ATRA/IL-2 treatment improved myeloid/DC ratio, DC function and antigen-specific T-cell response | RCC | 23 |

| CD14+ HLA-DR− SSCint | MDSC suppressed T cells via TGF-β | Melanoma | 24 |

| CD14+ HLA-DR−/lo CD11b+ CD14− CD15+ | MDSC were shown to be negatively associated with survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma | Renal cell carcinoma | 99 |

| CD11b+ CD14− CD15+ | Depletion of ARG-1+ G-MDSC restored T-cell proliferation, CD3ζ chain expression and IFN-γ production in vitro | Renal cell carcinoma | 26 |

| CD15+ FSClo SSChi | MDSC levels correlated with elevated plasma levels of ROS markers, low levels of CD3ζ chain and Th1 cytokines | Adenocarcinoma of pancreas, colon and breast | 25 |

| CD11b+ CD33+ HLA-DR− | Low-risk patients have increased levels of MDSC and higher serum titres of IL-10, IL-1β and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 compared with high-risk patients | Neuroblastoma | 28 |

| CD14+ CD33+ HLA-DR−/lo CD15+ CD33+ HLA-DR− | MDSC suppressed IFN-γ by T cells, increased ARG-1 and G-CSF plasma levels in patients, depletion of MDSC significantly restored effector T cells | Glioma | 34 |

| CD11b+ CD33+ HLA-DR− Lin1−/lo | MDSC levels correlated with ARG-1 and IL-13 production, increased Treg-cell levels, and an increased risk of death | Gastric, pancreatic oesophageal, carcinoma | |

| CD11b+ CD14+ CD33+ HLA-DR−/lo CD11b+ CD15+ CD33+ HLA-DR− | IL-6 correlated with CD15+ and IL-10 with CD15− MDSC, increased percentage of CD14+ and CD15+ MDSC was associated with increased risk of death. MDSC led to reduced IFN-α responsiveness of total PBMC and CD4+ T cells in vitro | Gastrointestinal malignancies | 98 |

| CD11b+ HLA-DR− Lin1− CD14+ HLA-DR− Lin1− CD15+ HLA-DR− Lin1− CD33+ HLA-DR− Lin1− | CD11b+ and CD14+ HLA-DR− Lin1− were resistant to cryopreservation; all subsets lost their suppressive capacity. | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma | 39 |

ARG-1, arginase-1; DC, dendritic cell; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; G-MDSC and M-MDSC, granulocytic and myeloid-derived suppressor cells; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; NK cells, natural killer cells; NOS, nitric oxide species; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TGF, transforming growth factor; Th1, T helper type 1; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; Treg, regulatory T cell; TSC, tumour stromal cell; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Immunosuppressive mechanisms of MDSC

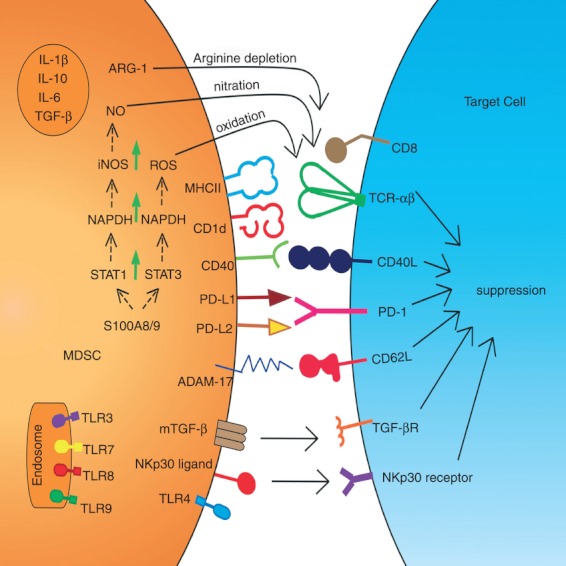

Both M-MDSC and G-MDSC apply antigen-specific and antigen non-specific mechanisms to regulate immune responses (Fig. 2). Interestingly, G-MDSC and M-MDSC can inhibit Teff cells through different modes of action, although these mechanisms are not exclusively used by one of the two subtypes.18,19 Production of ROS has been predominantly established for G-MDSC, whereas the generation of NO and secretion of ARG-1 is mainly used by M-MDSC.30,32,36 Production of ROS by MDSC is mediated through the increased activity of NADPH oxidase (NOX) 2. This membrane-bound enzyme complex is assembled during a respiratory burst to catalyse the one-electron reduction of oxygen to superoxide anion using electrons provided by NADPH. Corzo et al.42 identified up-regulation of ROS by Gr-1+ CD11b+ MDSC isolated from seven different tumour models and by CD11b+ CD14− CD33+ MDSC in patients with head and neck cancer. These MDSC showed significantly higher expression of the NOX2 subunits p47phox and gp91phox compared with immature myeloid cells from tumour-free mice.42 In the absence of NOX2 activity, MDSC lost the ability to control T-cell hyporesponsiveness and differentiated into mature DC.43 Indeed, MDSC from gp91−/− mice are not able to induce T-cell tolerance,43 confirming the role of ROS in T-cell suppression. The cooperative activity of ROS with NO forms peroxynitrite.18,19,29 Peroxynitrite leads to the nitration of tyrosines in the T-cell receptor (TCR)–CD8 complex.43 This reaction might affect the conformational flexibility of TCR-CD8 and its interaction with peptide-loaded MHCI, rendering the CD8+ T cells (cytotoxic T lymphocytes; CTL) unresponsive to antigen-specific stimulation.43 Indeed, nitration inhibits the binding of processed peptides to tumour cell-associated MHC, and as a result, tumour cells become resistant to antigen-specific TIL.44 Peroxynitrite can damage proteins in a wide array of different processes in both tumour and immune cells including those regulating MHCII expression and T-cell apoptosis.18,19 Furthermore, peroxynitrite leads to the nitration of CCL2 chemokines thereby inhibiting TIL trafficking into the tumour, resulting in trapping of antigen-specific CTL in the tumour-surrounding stroma.45 Another mechanism by which MDSC can interfere with T-cell trafficking is the expression of the disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain (ADAM) 17, which decreases CD62 ligand expression and renders T cells immobile.19 The suppressive activity of ARG-1 is based on its fundamental role in the hepatic urea cycle, metabolizing l-arginine to l-ornithine. Expression of ARG-1 has been reported to down-regulate TCR cell surface expression by decreasing CD3 ζ-chain biosynthesis.46 This effect is not a result of apoptosis, instead the diminished expression of CD3ζ protein is paralleled by a decrease in CD3ζ mRNA caused by a significantly shorter CD3ζ mRNA half-life. This provokes an arrest of T cells in the G0–G1 phase of the cell cycle, associated with a deficiency of protein kinase complexes that are important for G1 phase progression.31 In vitro, this phenomenon is completely reversed by the replenishment of l-arginine but not other amino acids.46 In vivo, the depletion of CD14− CD15+ G-MDSC re-established CD3ζ-chain biosynthesis and T-cell growth; further emphasizing the detrimental role that these MDSC play in cancer.26 Cancer-expanded MDSC can also induce anergy in NK cells through membrane bound TGF-β, STAT5 activity, ARG-1 or via the NKp30 receptor.47–50 The MDSC can suppress NK cell cytotoxicity by inhibiting NKG2D and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production in models of glioma.51 Another type of immunosuppression modulated by MDSC is the activation and expansion of Treg cells, which will be described in detail in the next section. Collectively, the data show that MDSC can employ a diverse set of distinct mechanisms to affect tumour cells, endothelial cells and immune cells to create a local environment that sustains tumour growth and survival while suppressing anti-tumour immune responses.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the different suppressive mechanisms employed by myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC). ADAM, disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain; ARG-1, arginase-1; IL, interleukin; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; MDSC, myeloid derived suppressor cell; NO, nitric oxide; PD, programmed death receptor; PD-L, programmed death receptor ligand; ROS, reactive oxygen species; S100A8/9, heterodimer S100A8/9 protein; STAT, signal transducers and activators of transcription; TGF, transforming growth factor; TLR, toll-like receptor.

MDSC and Treg-cell subsets

In addition to infiltrating myeloid cells, tumours harbour immunosuppressive CD4+ CD25hi FoxP3+ Treg cells. They include both thymus-derived natural Treg (nTreg) and locally induced Treg (iTreg) cells. Both subsets incorporate contact-dependent and contact-independent mechanisms to constrain the activation of effector T cells, and have been reviewed elsewhere.9 Naive CD4+ CD25− T cells can be converted into iTreg cells as a consequence of exposure to antigen in the presence of immunosuppressive conditions, including the presence of TGF-β or IL-10.52–54 Although they express distinct TCR repertoires, potentially use different suppressive mechanisms and show different survival and proliferation properties, phenotypical discrimination of these two Treg-cell subsets remains a major challenge.55 It will be extremely important to investigate the role of different myeloid cells, including MDSC, in the attraction and activation of Treg-cell subsets in general, and the induction of iTreg cells in particular. Mouse studies in vivo suggested that MDSC support the de novo development of Treg cells through TGF-β-dependent56,57 and -independent pathways.58 Yang et al.56 reported that suppression of Gr-1+ CD11b+ MDSC isolated from ovarian-carcinoma-bearing mice was dependent on the presence of CD80 on the MDSC and involved CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells and CD152, suggesting a relationship between MDSC and Treg cells. In a mouse colon carcinoma model, IFN-γ activated Gr-1+ CD115+ M-MDSC were shown to up-regulate MHCII and produce IL-10 and TGF-β to mediate the development of tumour-induced CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells. The production of NO by Gr-1+ CD115+ M-MDSC was required to suppress antigen-associated activation of tumour-specific T cells but was dispensable for Treg-cell induction.57 In this study, Gr-1+ CD115− G-MDSC did not induce the activation of tumour-specific Foxp3+ Treg cells.57 In a B-cell lymphoma model, MDSC were identified as tolerogenic APC capable of antigen uptake and presentation to tumour-specific Treg cells. These CD11b+ CD11clo MHCIIlo MDSC expressed ARG-1 to mediate the expansion of nTreg cells.58 The Gr-1+ CD115+ M-MDSC from CD40-deficient mice were not able to support tumour-specific Treg-cell expansion, implicating CD40/CD40L interactions between the two immunosuppressors.59 These data exemplify the relationship between MDSC and Treg cells. It will be important to further dissect the relative contributions of nTreg and iTreg cells in dampening T-cell immunity and the role that MDSC play in this process Recently Helios, a member of the Ikaros transcription factor family, was identified as a potential marker to discriminate between nTreg cells (Helios+) and iTreg cells (Helios−).60 However, its use to distinguish both lineages has been challenged because of the inconsistent expression on iTreg cells in different disease models.60–62 Two other studies reported that the cell surface molecule Neuropilin-1 (Nrp-1) is present at high levels on nTreg cells, whereas peripherally generated FoxP3+ iTreg cells lack Nrp-1 expression.63,64 By tracing nTreg and iTreg cells, Weiss et al.64 showed that intraperitoneal MCA38 colon adenocarcinomas are heavily infiltrated with FoxP3+ Nrp-1lo Helioslo iTreg cells. A subcutaneously growing 4T1 breast cancer cell line contained significant amounts of both FoxP3+ Nrp-1− iTreg cells and nTreg cells. These findings imply that different tumours exhibit different nTreg : iTreg ratios. Analysing both Treg-cell and MDSC subsets in different tumour settings is therefore important to uncover the conditions that determine the attraction and de novo generation of Treg cells. It will be a major challenge to change or alter the immunosuppressive MDSC and Treg cells that accumulate in the presence of a tumour. Depletion of Treg cells has been applied to enhance anti-cancer treatments aiming to boost tumour immune responses in mice and with some success in men.65–67 Other approaches that directly or indirectly affect or modulate immunosuppressive cells include ipilimumab and MDX-1106 mAb therapy that antagonize CTLA-4 and Programmed Death 1 (PD-1), respectively.68,69 Blocking members of the B7 family inhibitory molecules and/or their ligands (PDL-1 and PDL-2) may be highly beneficial as they are expressed not only on Treg cells but also on MDSC, tolerogenic DC and TIL.10,70–72 Recent multicentre phase 1 trials revealed durable tumour regression and prolonged disease stabilization in cancer patients by modulation of the PD-1–PD-L1 pathway.73,74 Likewise, strengthening the response of DC-based vaccines or adoptive TIL therapy could be dramatically enhanced by eliminating of MDSC or by converting them into stimulatory APC. Ultimately, effective immunocombination therapy may require the induction of potent immunity and attacking both suppressors simultaneously, as each subset may compensate for the other.

MDSC and NKT cells

Immune cells that are activated in response to bacterial and viral antigens presented by the MHCI-like molecule CD1d have been classified as type I and type II NKT cells.7 Type I NKT cells express a semi-invariant TCR-αβ encoded by the Vα14 (Vα24 in humans) and Jα18 gene segments, and therefore are also known as invariant NKT (iNKT) cells. In contrast, type II NKT (non-iNKT) cells express variable non-Vα14Jα18 TCR, are distinct from the Vα14+ iNKT cells, and potentially recognize a wider profile of glycolipid ligands.75,76 In mice and humans, iNKT cells have been identified using CD1d tetramers loaded with α-galactosyl ceramide (GalCer). Non-iNKT cells are less well characterized and have only been indirectly studied by comparing immune responses in mice either deficient in both subsets (CD1d−/−) or only iNKT cells (Jα18−/−).7 Stimulation of iNKT cells has been shown to be beneficial for the downstream activation of T and NK cells in experimental tumour models,7,77 whereas the activation of non-iNKT cells seems to be deleterious.7,78 This differential effect on tumours may be explained by cytokine profiles generated following the activation of each cell type. For example, presentation of α-GalCer by a DC to the TCR of iNKT cells led to the generation of IL-12, IFN-γ, tumour necrosis factor and the subsequent activation of anti-tumorigenic CTL.79 In contrast, the activation of non-iNKT cells through endogenous ligands, such as lysophosphatidylcholines,80 leads to the production of IL-4, IL-13 and TGF-β, which subsequently impairs CTL and NK cell functions.79,81 Interleukin-13 has been reported to mediate its effect via the IL-4R–STAT6 pathway and can induce TGF-β-producing CD11b+ Gr-1+ MDSC.82,83 Instead, Ko et al.84 showed that iNKT cells activated by α-GalCer-loaded CD11b+ Gr-1+ MDSC could convert these MDSC into stimulatory APC. Such reprogrammed MDSC up-regulated the expression of CD11b, CD11c and CD86, did not suppress Teff cells and thereby supported the generation of antigen-specific CTL immunity without increasing Treg-cell levels. The mechanism is not completely understood, but may involve soluble mediators and cell-to-cell contact interactions. Indeed, production of IFN-γ by α-GalCer-activated iNKT cells required direct CD40/CD40L interactions with DC. This interaction enhanced IL-12 secretion by DC and further functions to transactivate iNKT cells.85 In a mouse model of breast cancer, anti-tumour efficacy of CTL was partly dependent on the presence of ex vivo expanded iNKT cells that rendered these CTL more resistant to the immunosuppressive actions of MDSC.86 Furthermore, it has been proposed that activated iNKT cells can limit the growth of human neuroblastomas in NOD/SCID xenografts by selectively killing IL-6-producing CD1d+ CD68+ TAM.87 Additionally, it might be rewarding to investigate the interaction between iNKT cells and TAN, because iNKT cells from melanoma patients have been reported to modulate the suppressive capacity of serum amyloid A (SAA) -1 differentiated IL-10-secreting neutrophils by increasing the IL-12 production of these cells.88 SAA-1 promotes the interaction between iNKT cells and neutrophils in a CD1d-dependent and CD40-dependent manner, suggesting that iNKT cells can modulate the expansion and differentiation of neutrophils, possibly by interacting with CD1d+ immature myeloid cells in the bone marrow.88 In contrast, mature neutrophils can modulate IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor and IL-4 production by iNKT cells in mice and humans.89 Therefore, depending on the context, iNKT cells are able to potentiate pro-inflammatory neutrophil functions whereas neutrophils can down-regulate iNKT cell responses. To examine the interaction between iNKT cells and DC during the generation of anti-tumour immunity, Gillessen et al.90 vaccinated wild-type (WT), CD1d−/− and Jα18−/− mice with irradiated GM-CSF-secreting B16F10 melanoma cells. This vaccination strategy enhanced tumour antigen presentation by recruited CD8α− CD11c+ DC in WT mice. These DC expressed high levels of CD1d and macrophage inflammatory protein-2, a chemokine involved in iNKT-cell recruitment.91 Indeed, GM-CSF augmented the numbers of CD1d-restricted iNKT cells in vivo. In contrast, the vaccinated CD1d−/− and Jα18−/− mice lacked iNKT cell-mediated anti-tumour immunity and DC from CD1d−/− mice showed compromised maturation and function. These results provide further evidence for a role of iNKT–myeloid cell cross-talk shaping anti-tumour immunity.90 Furthermore, influenza A virus infected CD1d−/− mice provoke an expansion of immunosuppressive CD11b+ Ly-6G+ Ly-6C+ cells, which inhibits antigen-specific immune responses.92 In this model, adoptive transfer of iNKT cells abolished the suppressive activity of MDSC through CD1d-dependent and CD40-dependent interactions. As patients with cancer often have lower frequencies of iNKT cells than healthy donors,93,94 adoptive transfer of activated iNKT cells could become part of a treatment modality for cancer. Collectively, these findings show that NKT cells are potent immunomodulators of myeloid cells. Given their potential to influence anti-tumour effector activities, iNKT cells may represent an underestimated immune population to be used in cancer immunotherapy.7

MDSC in patients with cancer

The impact of MDSC on cancer progression is increasingly well understood, as is its dialogue with the TME that supports their proliferation, function and persistence. MDSC can synergize with Treg cells to prevent tumour immunity, whereas reciprocal communications with NKT cells can be either anti-tumorigenic or pro-tumorigenic. Most of these findings come from animal studies and it will be extremely important to determine whether they can be extrapolated to the human setting. Brimnes et al.95 revealed the presence of increased levels of CD14+ HLA-DR−/lo M-MDSC and of CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells in the blood of multiple myeloma patients at diagnosis relative to patients in remission. Functional data regarding the suppressive nature of the cells was, however, limited to the effects of Treg cells on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Levels of peripherally circulating CD11b+ CD33+ HLA-DR− Lin1−/lo MDSC have also been reported to correlate with clinical stage in breast cancer and gastrointestinal malignancies.96,97 Furthermore, in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies CD15+ MDSC levels correlated with elevated plasma levels of IL-6 whereas the CD15− MDSC subset revealed a strong correlation with IL-10.97 Similarly, elevated levels of CD11b+ CD33+ HLA-DR− Lin1−/lo MDSC may represent an independent prognostic factor in pancreatic, oesophageal and gastric cancers, which correlated with increased ARG-1 levels and significant production of the T helper type 2 cytokine IL-13, increased Treg-cell numbers, and increased risk of death.33 Although these human studies still provide little functional analysis on MDSC subsets and only marginally provide information on the cross-talk of MDSC, Treg cells and iNKT cells, they are among the first to discuss the prognostic significance of CD11b+ CD33+ HLA-DR− Lin1−/lo MDSC in tumour-bearing patients, and their potential role as markers for severity of the disease. Two clinical studies recently reported on specific immune responses to a renal cell carcinoma vaccine consisting of a multiple peptide cocktail (IMA901). Extensive pre-vaccination and post-vaccination immunophenotyping revealed that the presence of T-cell responses was associated with better disease control and lower numbers of pre-vaccine FoxP3+ Treg cells.98 In addition, CD14+ HLA-DR−/lo and CD11b+ CD14− CD15+ MDSC cells were shown to be negatively associated with survival in these patients with renal cell carcinomas. A comprehensive overview of the human studies is presented in Table 1. Future studies should provide further evidence for the prognostic and predictive value of the levels of the MDSC subsets in patients with cancer. It may indeed turn out to be highly rewarding to define the patients’ initial immune status, including the level of inflammation, frequencies of immunosuppressive cells as well as the quality of Teff cells, APC and NKT cells. Such an immunoscreening could aid in determining eligibility for therapies, including cancer immunotherapy.

Immunocombination therapy to modulate the immunosuppressive network

It will be a significant challenge to design combination therapies that target the tumour and eliminate or revert the immunosuppressive TME. To develop effective immunocombination therapy targeting MDSC, it is essential to dissect the signals and their pathways within the TME. For example, the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib represents a first-line treatment in advanced renal cell carcinoma that has been shown to decrease Treg-cell numbers in mice and humans,99,100 as well as the generation and suppressive activity of CD33+ HLA-DR− and CD15+ CD14− MDSC.101 Another stimulating agent for MDSC differentiation is all-trans-retinoic acid because it lowers the number of CD33+ HLA-DR− Lin1− MDSC and improves DC to promote tumour-specific T-cell responses in patients with metastatic kidney cancer.23 Potentially, reprogramming MDSC into stimulatory APC might be highly effective in combination with tumour antigen-specific immune cell activation by cancer vaccines. Which interactions or pathways in the TME should one target to eliminate or alter MDSC in immunocombination therapies? Based on the available murine data, iNKT cells could be part of such an approach.84,102 Also CD40/CD40L interactions may represent an interesting target to disturb MDSC/Treg-cell interactions or to mature MDSC.60,84,88 Macrophages activated by an agonist CD40 mAb can rapidly infiltrate tumours, become tumoricidal, and facilitate the depletion of tumour stroma independent from T cells and gemcitabine chemotherapy.103 The CD11b+ Gr-1+ MDSC are known to interact with antigen-specific CTL via the integrins CD11b, CD18 and CD29. Blocking of these integrins with specific mAb could be exploited as this was shown to abrogate ROS production and MDSC-mediated suppression of CTL.29 For reprogramming of MDSC, toll-like receptors (TLR) may be important because they provide an important link between innate and adaptive immunity. TLR-targeted therapeutics are increasingly used in the development of cancer vaccines and could therefore potentially be used to boost immune responses and to attack the TME.104 Interestingly, expression of TLR signalling genes is low in mature neutrophils but appear to be up-regulated in G-MDSC.37 Furthermore, exposure of CD11b+ Ly-6G+Ly-6C+ MDSC to TLR3, TLR7/8 or TLR9 agonists relieved or at least diminished their suppressive activity on T cells.92 The TLR ligand (TLRL) with the most potential for inducing the differentiation and blocking the immunosuppressive activity of mouse MDSC so far appears to be the TLR9L CpG.52,105,106 TLR9-expressing CD11b+ Ly-6G− Ly-6Chi M-MDSC respond to CpG stimulation by losing their ability to suppress Teff cells, producing Th1 cytokines, and differentiating into anti-tumorigenic macrophages.105 Zoglmeiner et al.106 could show that IFN-α produced by plasmacytoid DC after CpG stimulation in vitro or IFN-α treatment alone in vivo seems to be responsible for reprogramming CD11b+ Gr-1+ Ly-6Ghi MDSC. Therefore, TLR agonists that induce the production of IFN-α seem to have the capacity to change MDSC into non-suppressive APC, whereas TLR4L promote their inflammation-driven suppressive activity.19,41 Scarlett et al.71 merged the best of both worlds and co-administered synergistic CD40/TLR3 agonists to transform tolerogenic DC into immunostimulatory APC. In detail, in situ co-stimulation of CD40 and TLR3 on tolerogenic DC decreased their ARG-1 activity, enhanced their type I IFN and IL-12 production, promoted their ability to process antigen, and up-regulated CD40, CD70, CD80 and CD86 expression in vivo in mice and in vitro in human dissociated tumours. The transformation of these tolerogenic DC into APC further augmented their migration from tumours to lymph nodes, enhanced T-cell-mediated anti-tumour immunity and finally led to the rejection of intraperitoneal ovarian carcinomas in mice. Two recent pre-clinical studies highlight the TME complexity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.107,108 Both studies show that pancreas-specific oncogenic KRAS gene mutations initiate a molecular and cellular cascade in which the TME is forced to produce GM-CSF. This tumour-derived GM-CSF engages stromal Gr-1+ CD11b+ MDSC to inhibit CTL by ARG-1 and NOS production. Abrogation of GM-CSF with short hairpin RNA at the transcriptional level or anti-GM-CSF mAb reduced tumour growth and limited MDSC recruitment to the tumour site. These findings suggest that disruption of the cross-talk within the TME by targeting MDSC or the cytokines that regulate their recruitment may be beneficial for patients with pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma. In summary, effective immunocombination therapy may require induction of potent anti-tumour immunity and the elimination or reprogramming of the immunosuppressive and tumour-potentiating local environment. Treatment with differentiating/activating agents should possibly target Treg cells, NKT cells and MDSC in addition to tumour cells to make the TME more sensitive to cancer therapies, including immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported within the framework of grants by D1-101 of Top Institute Pharma, Villa Joep and KOC awarded to G.J.A. and by grants from the Stichting STOPhersentumoren and the RUNMC RUCO institute to G.J.A. and P.W.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dougan M, Dranoff G. Immune therapy for cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:83–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nierkens S, Den Brok MH, Roelofsen T, Wagenaars JA, Figdor CG, Ruers TJ, Adema GJ. Route of administration of the TLR9 agonist CpG critically determines the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy in mice. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tacken PJ, Zeelenberg IS, Cruz LJ, Van Hout-Kuijer MA, Van de Glind G, Fokkink RG, Lambeck AJ, Figdor CG. Targeted delivery of TLR ligands to human and mouse dendritic cells strongly enhances adjuvanticity. Blood. 2011;118:6836–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-367615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vesely MD, Kershaw MH, Schreiber RD, Smyth MJ. Natural innate and adaptive immunity to cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:235–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vivier E, Ugolini S, Blaise D, Chabannon C, Brossay L. Targeting natural killer cells and natural killer T cells in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:239–52. doi: 10.1038/nri3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platonova S, Cherfils-Vicini J, Damotte D, et al. Profound coordinated alterations of intratumoral NK cell phenotype and function in lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5412–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs JF, Nierkens S, Figdor CG, De Vries IJ, Adema GJ. Regulatory T cells in melanoma: the final hurdle towards effective immunotherapy? Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e32–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs JF, Idema AJ, Bol KF, et al. Regulatory T cells and the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway mediate immune suppression in malignant human brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11:394–402. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiniwa Y, Miyahara Y, Wang HY, et al. CD8+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells mediate immunosuppression in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6947–58. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olkhanud PB, Damdinsuren B, Bodogai M, et al. Tumor-evoked regulatory B cells promote breast cancer metastasis by converting resting CD4+ T cells to T-regulatory cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3505–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hix LM, Shi YH, Brutkiewicz RR, Stein PL, Wang CR, Zhang M. CD1d-expressing breast cancer cells modulate NKT cell-mediated antitumor immunity in a murine model of breast cancer metastasis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e20702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Palma M, Venneri MA, Galli R, Sergi Sergi L, Politi LS, Sampaolesi M, Naldini L. Tie2 identifies a hematopoietic lineage of proangiogenic monocytes required for tumor vessel formation and a mesenchymal population of pericyte progenitors. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:211–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watkins SK, Zhu Z, Riboldi E, et al. FOXO3 programs tumor-associated DCs to become tolerogenic in human and murine prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1361–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI44325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–96. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kim S, Kapoor V, Cheng G, Ling L, Worthen GS, Albelda SM. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-β: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–74. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:253–68. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer C, Sevko A, Ramacher M, et al. Chronic inflammation promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell activation blocking antitumor immunity in transgenic mouse melanoma model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17111–16. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108121108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corzo CA, Condamine T, Lu L, et al. HIF-1α regulates function and differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2439–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandruzzato S, Solito S, Falisi E, et al. IL4Rα+ myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion in cancer patients. J Immunol. 2009;182:6562–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirza N, Fishman M, Fricke I, et al. All-trans-retinoic acid improves differentiation of myeloid cells and immune response in cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9299–307. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filipazzi P, Valenti R, Huber V, et al. Identification of a new subset of myeloid suppressor cells in peripheral blood of melanoma patients with modulation by a granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulation factor-based antitumor vaccine. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2546–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmielau J, Finn OJ. Activated granulocytes and granulocyte-derived hydrogen peroxide are the underlying mechanism of suppression of T-cell function in advanced cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4756–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zea AH, Rodriguez PC, Atkins MB, et al. Arginase-producing myeloid suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma patients: a mechanism of tumor evasion. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3044–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poschke I, Mougiakakos D, Hansson J, Masucci GV, Kiessling R. Immature immunosuppressive CD14+HLA-DR–/low cells in melanoma patients are Stat3hi and overexpress CD80, CD83, and DC-sign. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4335–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gowda M, Godder K, Kmieciak M, Worschech A, Ascierto ML, Wang E, Marincola FM, Manjili MH. Distinct signatures of the immune responses in low risk versus high risk neuroblastoma. J Transl Med. 2011;9:170. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kusmartsev S, Nefedova Y, Yoder D, Gabrilovich DI. Antigen-specific inhibition of CD8+ T cell response by immature myeloid cells in cancer is mediated by reactive oxygen species. J Immunol. 2004;172:989–99. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:5791–802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodriguez PC, Ernstoff MS, Hernandez C, Atkins M, Zabaleta J, Sierra R, Ochoa AC. Arginase I-producing myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma are a subpopulation of activated granulocytes. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1553–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dolcetti L, Peranzoni E, Ugel S, et al. Hierarchy of immunosuppressive strength among myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets is determined by GM-CSF. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:22–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gabitass RF, Annels NE, Stocken DD, Pandha HA, Middleton GW. Elevated myeloid-derived suppressor cells in pancreatic, esophageal and gastric cancer are an independent prognostic factor and are associated with significant elevation of the Th2 cytokine interleukin-13. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:1419–30. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raychaudhuri B, Rayman P, Ireland J, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation and function in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:591–9. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waight JD, Hu Q, Miller A, Liu S, Abrams SI. Tumor-derived G-CSF facilitates neoplastic growth through a granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell-dependent mechanism. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, Van den Bergh R, Gysemans C, Beschin A, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111:4233–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Mishalian I, et al. Transcriptomic analysis comparing tumor-associated neutrophils with granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells and normal neutrophils. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6Chigh monocytes. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5728–39. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotsakis A, Harasymczuk M, Schilling B, Georgoulias V, Argiris A, Whiteside TL. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell measurements in fresh and cryopreserved blood samples. J Immunol Methods. 2012;381:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marigo I, Bosio E, Solito S, et al. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPβ transcription factor. Immunity. 2010;32:790–802. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao F, Hoechst B, Duffy A, Gamrekelashvili J, Fioravanti S, Manns MP, Greten TF, Korangy F. S100A9 a new marker for monocytic human myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Immunology. 2012;136:176–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corzo CA, Cotter MJ, Cheng P, et al. Mechanism regulating reactive oxygen species in tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5693–701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagaraj S, Gupta K, Pisarev V, et al. Altered recognition of antigen is a mechanism of CD8+ T cell tolerance in cancer. Nat Med. 2007;13:828–35. doi: 10.1038/nm1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu T, Ramakrishnan R, Altiok S, et al. Tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells induce tumor cell resistance to cytotoxic T cells in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4015–29. doi: 10.1172/JCI45862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molon B, Ugel S, Del Pozzo F, et al. Chemokine nitration prevents intratumoral infiltration of antigen-specific T cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1949–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez PC, Zea AH, Culotta KS, Zabaleta J, Ochoa JB, Ochoa AC. Regulation of T cell receptor CD3ζ chain expression by l-arginine. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21123–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110675200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H, Han Y, Guo Q, Zhang M, Cao X. Cancer-expanded myeloid-derived suppressor cells induce anergy of NK cells through membrane-bound TGF-β1. J Immunol. 2009;182:240–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu C, Yu S, Kappes J, Wang J, Grizzle WE, Zinn KR, Zhang HG. Expansion of spleen myeloid suppressor cells represses NK cell cytotoxicity in tumor-bearing host. Blood. 2007;109:4336–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoechst B, Voigtlaender T, Ormandy L, et al. Myeloid derived suppressor cells inhibit natural killer cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma via the NKp30 receptor. Hepatology. 2009;50:799–807. doi: 10.1002/hep.23054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oberlies J, Watzl C, Giese T, Luckner C, Kropf P, Muller I, Ho AD, Munder M. Regulation of NK cell function by human granulocyte arginase. J Immunol. 2009;182:5259–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alizadeh D, Zhang L, Brown CE, Farrukh O, Jensen MC, Badie B. Induction of anti-glioma natural killer cell response following multiple low-dose intracerebral CpG therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3399–408. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N, McGrady G, Wahl SM. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25– naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-β induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu P, Lee Y, Liu W, Krausz T, Chong A, Schreiber H, Fu YX. Intratumor depletion of CD4+ cells unmasks tumor immunogenicity leading to the rejection of late-stage tumors. J Exp Med. 2005;201:779–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghiringhelli F, Puig PE, Roux S, et al. Tumor cells convert immature myeloid dendritic cells into TGF-β-secreting cells inducing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell proliferation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:919–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim YC, Bhairavabhotla R, Yoon J, Golding A, Thornton AM, Tran DQ, Shevach EM. Oligodeoxynucleotides stabilize Helios-expressing Foxp3+ human T regulatory cells during in vitro expansion. Blood. 2012;119:2810–18. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang R, Cai Z, Zhang Y, Yutzy W, Roby KF, Roden RB. CD80 in immune suppression by mouse ovarian carcinoma-associated Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6807–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang B, Pan PY, Li Q, Sato AI, Levy DE, Bromberg J, Divino CM, Chen SH. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1123–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Serafini P, Mgebroff S, Noonan K, Borrello I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote cross-tolerance in B-cell lymphoma by expanding regulatory T cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5439–49. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pan PY, Ma G, Weber KJ, Ozao-Choy J, Wang G, Yin B, Divino CM, Chen SH. Immune stimulatory receptor CD40 is required for T-cell suppression and T regulatory cell activation mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:99–108. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, Wohlfert EA, Murray PE, Belkaid Y, Shevach EM. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3433–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gottschalk RA, Corse E, Allison JP. Expression of Helios in peripherally induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2012;188:976–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Akimova T, Beier UH, Wang L, Levine MH, Hancock WW. Helios expression is a marker of T cell activation and proliferation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yadav M, Louvet C, Davini D, et al. Neuropilin-1 distinguishes natural and inducible regulatory T cells among regulatory T cell subsets in vivo. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1713–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weiss JM, Bilate AM, Gobert M, et al. Neuropilin 1 is expressed on thymus-derived natural regulatory T cells, but not mucosa-generated induced Foxp3+ T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1723–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grauer OM, Sutmuller RP, Van Maren W, Jacobs JF, Bennink E, Toonen LW, Nierkens S, Adema GJ. Elimination of regulatory T cells is essential for an effective vaccination with tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells in a murine glioma model. Int J Cancer Suppl. 2008;122:1794–802. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jacobs JF, Punt CJ, Lesterhuis WJ, et al. Dendritic cell vaccination in combination with anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody treatment: a phase I/II study in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5067–78. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Onizuka S, Tawara I, Shimizu J, Sakaguchi S, Fujita T, Nakayama E. Tumor rejection by in vivo administration of anti-CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor α) monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3128–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3167–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ozao-Choy J, Ma G, Kao J, et al. The novel role of tyrosine kinase inhibitor in the reversal of immune suppression and modulation of tumor microenvironment for immune-based cancer therapies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2514–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scarlett UK, Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Nesbeth YC, Martinez DG, Engle X, Gewirtz AT, Ahonen CL, Conejo-Garcia JR. In situ stimulation of CD40 and Toll-like receptor 3 transforms ovarian cancer-infiltrating dendritic cells from immunosuppressive to immunostimulatory cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7329–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Norde WJ, Maas F, Hobo W, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 interactions contribute to functional T-cell impairment in patients who relapse with cancer after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5111–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bendelac A, Lantz O, Quimby ME, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR, Brutkiewicz RR. CD1 recognition by mouse NK1+ T lymphocytes. Science. 1995;268:863–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7538697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kinjo Y, Wu D, Kim G, et al. Recognition of bacterial glycosphingolipids by natural killer T cells. Nature. 2005;434:520–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nowak M, Arredouani MS, Tun-Kyi A, Schmidt-Wolf I, Sanda MG, Balk SP, Exley MA. Defective NKT cell activation by CD1d+ TRAMP prostate tumor cells is corrected by interleukin-12 with α-galactosylceramide. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ambrosino E, Terabe M, Halder RC, et al. Cross-regulation between type I and type II NKT cells in regulating tumor immunity: a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol. 2007;179:5126–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fujii S, Shimizu K, Smith C, Bonifaz L, Steinman RM. Activation of natural killer T cells by α-galactosylceramide rapidly induces the full maturation of dendritic cells in vivo and thereby acts as an adjuvant for combined CD4 and CD8 T cell immunity to a coadministered protein. J Exp Med. 2003;198:267–79. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chang DH, Deng H, Matthews P, et al. Inflammation-associated lysophospholipids as ligands for CD1d-restricted T cells in human cancer. Blood. 2008;112:1308–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Crane CA, Han SJ, Barry JJ, Ahn BJ, Lanier LL, Parsa AT. TGF-β downregulates the activating receptor NKG2D on NK cells and CD8+ T cells in glioma patients. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:7–13. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Terabe M, Matsui S, Noben-Trauth N, et al. NKT cell-mediated repression of tumor immunosurveillance by IL-13 and the IL-4R-STAT6 pathway. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:515–20. doi: 10.1038/82771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Terabe M, Matsui S, Park JM, et al. Transforming growth factor-β production and myeloid cells are an effector mechanism through which CD1d-restricted T cells block cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated tumor immunosurveillance: abrogation prevents tumor recurrence. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1741–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ko HJ, Lee JM, Kim YJ, Kim YS, Lee KA, Kang CY. Immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells can be converted into immunogenic APCs with the help of activated NKT cells: an alternative cell-based antitumor vaccine. J Immunol. 2009;182:1818–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kitamura H, Iwakabe K, Yahata T, et al. The natural killer T (NKT) cell ligand α-galactosylceramide demonstrates its immunopotentiating effect by inducing interleukin (IL)-12 production by dendritic cells and IL-12 receptor expression on NKT cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1121–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kmieciak M, Basu D, Payne KK, et al. Activated NKT cells and NK cells render T cells resistant to myeloid-derived suppressor cells and result in an effective adoptive cellular therapy against breast cancer in the FVBN202 transgenic mouse. J Immunol. 2011;187:708–17. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Song L, Asgharzadeh S, Salo J, et al. Vα24-invariant NKT cells mediate antitumor activity via killing of tumor-associated macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1524–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI37869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.De Santo C, Arscott R, Booth S, et al. Invariant NKT cells modulate the suppressive activity of IL-10-secreting neutrophils differentiated with serum amyloid A. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1039–46. doi: 10.1038/ni.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wingender G, Hiss M, Engel I, Peukert K, Ley K, Haller H, Kronenberg M, Von Vietinghoff S. Neutrophilic granulocytes modulate invariant NKT cell function in mice and humans. J Immunol. 2012;188:3000–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gillessen S, Naumov YN, Nieuwenhuis EE, et al. CD1d-restricted T cells regulate dendritic cell function and antitumor immunity in a granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor-dependent fashion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8874–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1033098100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Faunce DE, Sonoda KH, Stein-Streilein J. MIP-2 recruits NKT cells to the spleen during tolerance induction. J Immunol. 2001;166:313–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.De Santo C, Salio M, Masri SH, et al. Invariant NKT cells reduce the immunosuppressive activity of influenza A virus-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:4036–48. doi: 10.1172/JCI36264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dhodapkar MV, Geller MD, Chang DH, Shimizu K, Fujii S, Dhodapkar KM, Krasovsky J. A reversible defect in natural killer T cell function characterizes the progression of premalignant to malignant multiple myeloma. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1667–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Molling JW, Langius JA, Langendijk JA, et al. Low levels of circulating invariant natural killer T cells predict poor clinical outcome in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:862–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brimnes MK, Vangsted AJ, Knudsen LM, Gimsing P, Gang AO, Johnsen HE, Svane IM. Increased level of both CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and CD14+HLA-DR–/low myeloid-derived suppressor cells and decreased level of dendritic cells in patients with multiple myeloma. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72:540–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Diaz-Montero CM, Salem ML, Nishimura MI, Garrett-Mayer E, Cole DJ, Montero AJ. Increased circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with clinical cancer stage, metastatic tumor burden, and doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0523-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mundy-Bosse BL, Young GS, Bauer T, et al. Distinct myeloid suppressor cell subsets correlate with plasma IL-6 and IL-10 and reduced interferon-α signaling in CD4+ T cells from patients with GI malignancy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:1269–79. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1029-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Walter S, Weinschenk T, Stenzl A, et al. Multipeptide immune response to cancer vaccine IMA901 after single-dose cyclophosphamide associates with longer patient survival. Nat Med. 2012;18:1254–61. doi: 10.1038/nm.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Finke JH, Rini B, Ireland J, et al. Sunitinib reverses type-1 immune suppression and decreases T-regulatory cells in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6674–82. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hipp MM, Hilf N, Walter S, et al. Sorafenib, but not sunitinib, affects function of dendritic cells and induction of primary immune responses. Blood. 2008;111:5610–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ko JS, Zea AH, Rini BI, et al. Sunitinib mediates reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2148–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee JM, Seo JH, Kim YJ, Kim YS, Ko HJ, Kang CY. The restoration of myeloid-derived suppressor cells as functional antigen-presenting cells by NKT cell help and all-trans-retinoic acid treatment. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:741–51. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Beatty GL, Chiorean EG, Fishman MP, et al. CD40 agonists alter tumor stroma and show efficacy against pancreatic carcinoma in mice and humans. Science. 2011;331:1612–16. doi: 10.1126/science.1198443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kanzler H, Barrat FJ, Hessel EM, Coffman RL. Therapeutic targeting of innate immunity with Toll-like receptor agonists and antagonists. Nat Med. 2007;13:552–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shirota Y, Shirota H, Klinman DM. Intratumoral injection of CpG oligonucleotides induces the differentiation and reduces the immunosuppressive activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2012;188:1592–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zoglmeier C, Bauer H, Norenberg D, et al. CpG blocks immunosuppression by myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1765–75. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bayne LJ, Beatty GL, Jhala N, Clark CE, Rhim AD, Stanger BZ, Vonderheide RH. Tumor-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid inflammation and T cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:822–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Lee KE, Hajdu CH, Miller G, Bar-Sagi D. Oncogenic Kras-induced GM-CSF production promotes the development of pancreatic neoplasia. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:836–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]