Abstract

Background

Carbohydrate intolerance is the most common metabolic complication of pregnancy. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) poses numerous problems for both mother and fetus. The objective of this study was to compare the maternal and perinatal outcome between women with gestational diabetes mellitus and non-diabetic women.

Study Design

A case–control study with 286 cases and 292 age-matched controls was conducted for a period of 11 months (August 2007–June 2008) in Sree Avittom Thirunal Hospital, Thiruvananthapuram, India.

Materials and Methods

Universal screening was applied by means of glucose challenge test (GCT) using 50 g of glucose. If GCT >130 mg%, the patients were subjected to oral glucose tolerance test with 100 g of glucose. National Diabetes Data Group criteria was taken to assign patients to study group. These women were further followed up and the maternal and perinatal outcomes were assessed.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analysis was done by means of t test, Odd’s ratio, Chi-square test, and Fisher Exact test. P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results

The frequency of induction of labor was significantly higher than spontaneous labor (OR = 1.84, P = 0.001). 40.1 % GDM mothers and 35.8 % of non-diabetic mothers were delivered by Cesarean section. Premature rupture of membranes (PROM) was the most common complication of labor (OR = 1.66, P = 0.04). Babies of diabetic mothers had a positive trend toward prematurity (OR = 2.3, P = 0.007). Hypoglycemia was the most common neonatal complication (OR = 11.97, P < 0.001) and nine babies of diabetic mothers were macrosomic (OR = 5.2, P = 0.02).

Conclusions

Maternal morbidities and neonatal complications such as neonatal hypoglycemia, macrosomia, and prematurity were significantly higher in GDM.

Keywords: Gestational diabetes mellitus, Outcome, Chi-square test, Odd’s ratio

Introduction

The International Diabetes Federation estimated that currently there are 100 million people with diabetes worldwide representing about 6 % of all adults [1]. Indeed, the number of people with diabetes in India is likely to double in less than 2 decades, from 39.9 million (in 2007) to 69.9 million by 2025 [2, 3]. The Indian Council of Medical Research study done in the 1970s reported a prevalence of 2.3 % in urban areas [4, 5] which has risen to 12–19 % in 2000s. These numbers also include gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and should alert the physicians to direct special attention to this population, especially in developing countries like India.

Babies born to mothers with GDM are at increased risk of complications, primarily growth abnormalities and chemical imbalances such as hypoglycemia [6, 7]. GDM is a reversible condition and women who have adequate control of glucose levels can effectively decrease the associated risks and give birth to healthy babies. Through improved understanding of pathophysiology of diabetes in pregnancy, as well as implementation of care programs emphasizing normalization of maternal glucose levels, fetal and neonatal mortality have been reduced from ~65 % before the discovery of insulin to 2–5 % at the present time. If optimal care is delivered to the diabetic mother, the perinatal mortality rate, excluding major congenital anomalies, is nearly equivalent to that observed in normal pregnancy.

As opposed to GDM, there are studies which confirm poorer maternal and fetal outcome like abortions and congenital anomalies in pre-gestational diabetes mellitus (PGDM) [8, 9]. Moreover, there are no studies on the outcome of GDM mothers conducted in Kerala. Studies of such nature will be a useful tool to know and compare the severity of outcomes, planning, and allocation of resources in the management of GDM mothers in developing countries like India. In this background, the present study was conducted to determine the outcome of GDM in a tertiary care hospital in Kerala.

Materials and Methods

This case–control study was carried out at Sri Avittom Thirunal Hospital, Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, South India, from August 2007 to June 2008. This is a tertiary care hospital and its maternity service is a referral centre in the care of high risk pregnant women throughout the district. For an alpha error of 5 %, for a power of 80 %, assuming the prevalence of GDM in India as 16.55 % [10] and odds ratio of 2, minimum sample size was estimated to be 215, each for cases and controls.

Selection Criteria for Study Group

The study group included women who developed carbohydrate intolerance of varying severity with onset or first detection in present pregnancy. The antenatal women were monitored with glucose challenge test (GCT) at 24–28 and 32–34 weeks, or whenever any risk factor developed during pregnancy. They were given a 50 g GCT, and if the plasma glucose value exceeded 130 mg/dl, a 100 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed after overnight fasting. For the purpose of this study, GDM cases were selected based on American Diabetes Association (ADA) National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) revised criteria of O’Sullivan and Mahan criteria [11].

Exclusion Criteria

Women with a diagnosis of diabetes before pregnancy, twin pregnancy, pre-existing hypertension, autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, and other chronic conditions such as chronic renal failure, congestive heart failure, and active tuberculosis were excluded.

Control Group

Pregnant women who had a normal GCT with 50 g of glucose at 24–28 weeks, followed by a normal OGTT with 100 g of glucose. Next normal case of the same age, after a study case, was taken as a control.

After the diagnosis of GDM was made, patients were prescribed a diabetic diet depending on their body mass index (BMI). After 2 weeks on the diet, the glycemic profile measuring the venous glucose level was performed in the fasting state and also 2 h after each main meal. If the fasting glucose concentration was ≤95 mg/dl, and 2 h after each meal ≤120 mg/dl, dietary recommendation was considered adequate. If these values were exceeded, provided there was good compliance by the patient to her diet, the patient was admitted and started on insulin treatment [12]. Insulin was started at the lowest dose and titrated according to the blood sugar levels. Oral hypoglycemic agent like metformin was not used for optimal glycemic control as their safety in pregnancy was not established.

Antenatal fetal surveillance was initiated depending on the severity of carbohydrate intolerance. Vaginal delivery was encouraged in all cases. Cesarean section was done for obstetric indications. The pregnancy outcome was assessed as regards to (a) maternal factors such as spontaneous/induced deliveries, vaginal/cesarean section, and premature rupture of membranes (PROM); and (b) fetal factors such as macrosomia, congenital anomalies, sepsis, respiratory distress, hypoglycemia, and prematurity. Macrosomia was defined as birth weight ≥4,000 g; neonatal hypoglycemia was defined as a blood glucose value <44 mg/dl during the first 48 h of life.

As appropriate, Student’s t test was used to compare groups for continuous variables, while Chi-square test or Fishers’ exact test was used to compare proportions. Odd’s ratio was calculated and all the computations were done by computer software, statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 10. Data obtained were compared in percentages and means. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

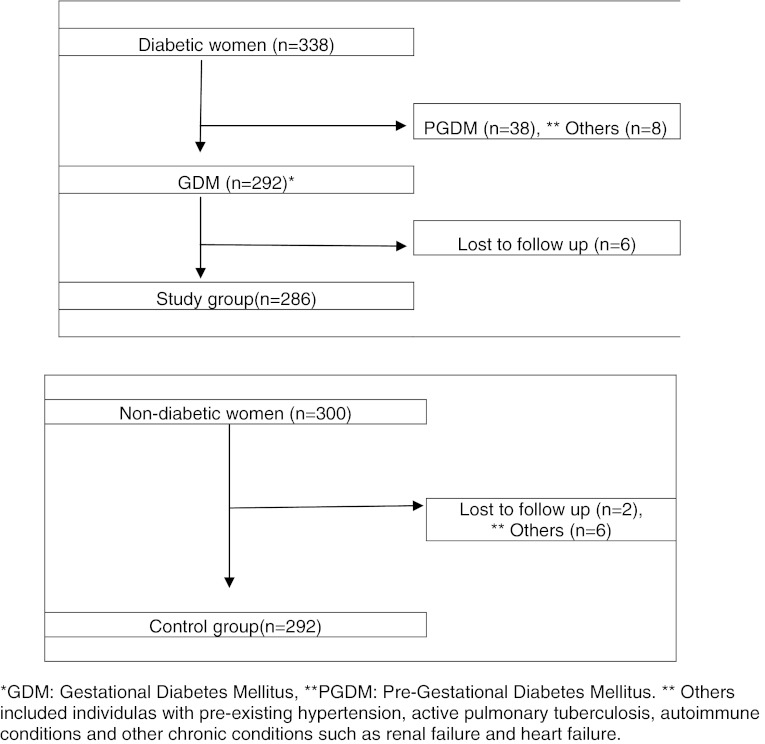

During the study period from August 2007 to June 2008, a total number of 338 cases of diabetes complicating pregnancy were selected. Of these patients selected, 46 were excluded in accordance to the exclusion criteria. The remaining 292 patients were included in our study as cases and compared with 294 age-matched controls. 6 patients in the study group and 2 patients in the control group were lost to follow-up. Thus, in total there were 286 cases and 292 controls available for follow-up (Fig. 1). The mean age of cases was 26.63 ± 4.547 years and the mean age of controls was 26.43 ± 4.412 years. The t test showed no significant difference between the two (t = −0.4: df = 298; P = 0.7).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of cases and controls

Majority of them were housewives (>95 %) and led a sedentary lifestyle (χ2 = 8.12, P = 0.02). In this study, the association between pre-eclampsia and GDM was found to be significant (29.3 vs. 18.7 %, P = 0.002).

58.7 % of the study group had induced labor as against 43.6 % of the control group (OR = 1.84, P = 0.001). Hence, induced labors were more in the study group, while spontaneous deliveries were more in the control group. 40.1 % of the study group had a cesarean section as compared to 35.8 % of the control group. Although not significant in this study, this shows a trend toward a higher incidence of cesarean section in patients with diabetes complicating pregnancy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Maternal Outcome

| Maternal outcome | Cases n (%) | Controls n (%) | Odd’s ratio (95 % CI) | χ2, P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H/o pre-eclampsia | ||||

| Present | 87 (29.3) | 54 (18.7) | 1.81 (1.23–2.65) | 9.36, 0.002* |

| Absent | 205 (70.7) | 240 (81.3) | ||

| Type of labor | ||||

| Induced | 125 (58.7) | 101 (43.6) | 1.84 (1.27–2.67) | 10.33, 0.001* |

| Spontaneous | 89 (41.3) | 130 (56.4) | ||

| Vaginal delivery | ||||

| Yes | 174 (59.9) | 186 (64.2) | 0.85 (0.61–1.18) | 0.9, 0.33 |

| No | 112 (40.1) | 106 (35.8) | ||

| LSCS | ||||

| Yes | 114 (40.1) | 106 (35.8) | 1.18 (0.85–1.64) | 0.9, 0.33 |

| No | 172 (59.9) | 186 (64.2) | ||

| PROM | ||||

| Yes | 45 (15.6) | 30 (10.1) | 1.66 (1.01–2.71) | 4.12, 0.04* |

| No | 247 | 264 | ||

LSCS lower segment cesarean section, PROM premature rupture of membranes

* P < 0.05 is considered as significant

Maternal complications like PROM and indications of cesarean section like cephalopelvic disproportion, fetal distress, and meconium were compared. It was observed that PROM was the most common complication and was found to be significant (OR = 1.66, P = 0.04). However, fetal distress was in same proportion, while meconium staining was observed to be more in non-diabetics (4.1 % cases vs. 8.1 % controls) (Table 1).

There were nine macrosomic babies (>4 kg) in the study group, while 2 in the control group. Higher incidence of macrosomia was seen in the cases (P = 0.02). 6.1 % of cases and 3.4 % of controls delivered babies with some congenital anomalies. Neonatal complications like prematurity, sepsis, respiratory distress, and hypoglycemia were studied. It was observed that there was a positive tend toward prematurity in neonates of diabetic mothers (OR = 11.97, P = 0.061) and the incidence of hypoglycemia in the newborn was found to be higher in the neonates of GDM mothers (7.5 vs. 0.7 %), which was statistically highly significant (P < 0.001). However, respiratory distress was almost the same in the two groups. 27.9 % babies of GDM mothers had perinatal morbidity as against 21.5 % of babies of non-GDM mothers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Neonatal outcome

| Neonatal outcome | Cases n (%) | Controls n (%) | Odd’s ratio (95 % CI) | χ2, P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maturity | ||||

| Preterm | 33 (11.6) | 15 (5.4) | 2.30 (1.24–4.27) | 7.4, 0.007* |

| Term | 253 (88.4) | 277 (94.6) | ||

| Hypoglycemia | ||||

| Yes | 20 (7.5) | 2 (0.7) | 11.97 (2.79–51.38) | 17.7, <0.001* |

| No | 266 (92.5) | 290 (99.3) | ||

| Sepsis | ||||

| Present | 21 (7.5) | 16 (6.0) | 1.26 (0.66–2.40) | 0.49, 0.08 |

| Absent | 265 (92.5) | 276 (94) | ||

| Respiratory distress | ||||

| Present | 24 (8.8) | 27 (9.4) | 0.94 (0.53–1.64) | 0.05, 0.82 |

| Absent | 262 (91.2) | 265 (90.6) | ||

| Perinatal mortality | ||||

| Yes | 4 (1.4) | 5 (2.0) | 0.67 (0.19–2.40) | 0.4, 0.54 |

| No | 282 (98.6) | 287 (98.0) | ||

| Macrosomia | ||||

| Yes | 9 (3.4) | 2 (0.7) | 5.2 (1.13–23.99) | 5.55, 0.02* |

| No | 277 (96.6) | 290 (99.3) | ||

* P < 0.05 is considered as significant

Discussion

Very few studies are available from India assessing the outcome of GDM [8, 9]. Our study conducted in a district government tertiary care hospital highlights the importance of taking proper antenatal care in the case of GDM mothers to prevent perinatal morbidity and mortality both for the mother and child, especially in an area where the prevalence of gestational diabetes is relatively very high. GDM cases were found to be more among housewives who led a sedentary life style (95.3 %) with a predisposition to higher BMI.

Maternal Outcome

Pre-eclampsia was significantly associated with GDM in our study. Overall, observational studies have shown mixed results and are inconclusive as to whether women with GDM have a higher risk for pre-eclampsia than women without GDM [13, 14]. Recent data from untreated women with GDM reveal a rate of pre-eclampsia (about 9 %) that is similar to that of treated women and women without GDM [15, 16].

It was observed that GDM mothers had increased frequency of induced deliveries as compared to spontaneous deliveries. There was an increased incidence of cesarean section in GDM patients (40.1 % of diabetic pregnancies vs. 35.8 % of non-diabetic pregnancies). In order to balance the increased risk of antepartum stillbirths and delayed lung maturity in diabetic pregnancies, there was a trend to induce such women at 38 weeks unless they went into spontaneous labor. According to a recent study in 2007, the rate of cesarean sections and inductions of labor were increased in the GDM mothers [17]. This was also in agreement to other similar studies [13, 18].

Of the maternal complications, 15.6 % had PROM with others showing a lower incidence, and this was statistically significant in the GDM group. If diabetes is well controlled, the chances of maternal morbidity is low. A study in 2006 concluded that women with GDM who were diagnosed and treated following treatment guidelines demonstrated no severe maternal and neonatal complications [19].

Fetal Outcome

The incidence of macrosomia in GDM mothers was 3.4 %, while 0.7 % in non-diabetic mothers, which was statistically significant. Previous studies revealed that macrosomic babies were associated with history of prior GDM pregnancy and pre-pregnancy BMI ≥25. [20, 21] A study diagnosed shoulder dystocia in 3 % of women with class A1 diabetes. Fortunately, shoulder dystocia was uncommon even in women with GDM.

Of the total deliveries, 11.6 % of cases delivered premature babies while 5.4 % of the babies of control group were preterm, which was statistically significant (P = 0.007). Owing to the increased liquor which has been reported as an important association in our study as well, there was higher chance of the GDM mothers to go into preterm labor and prematurity.

Among the babies delivered, the incidence of in-born nursery (IBN) admission for babies of GDM mothers was more for various reasons like sepsis (7.5 %), hypoglycemia (7.5 %), prematurity (11.6 %), respiratory distress (8.8 %), and congenital anomalies (6.4 %).

One of the complications observed was hypoglycemia, which was also found to be statistically significant. A study reported that 4 % of infants of women with GDM required intravenous glucose therapy for hypoglycemia [22]. Another study concluded from the cross-sectional study of 162 gestational diabetes women that the most common neonatal complication was hypoglycemia (n = 111, 68.5 %) and macrosomia was found in 29 cases (17.9 %) [19]. The perinatal mortality between the two groups was not significantly different. The likelihood of fetal death with appropriately treated GDM has been found no different than in the general population [12].

This study provides valuable information with regards to outcome of GDM from a district hospital in this region, which could help with possible intervention regarding maternal and newborn health in the future. The problem of recall bias was considered to be minimal since the study was designed as a follow-up study. This government hospital-based case–control study, which caters to women from lower and middle socio-economic class for antenatal care may involve selection bias to a certain extent. However, the possibility of selection bias may be more in private hospitals where women from affluent urban population come for delivery. Study population was relatively small for the estimation of risk of congenital anomalies in babies of diabetic mothers. The use of oral hypoglycemic agents, like metformin, for the optimal glycemic control during pregnancy was not recommended during the study period. Hence, this study is unable to comment upon the added advantage of their usage in the outcome of GDM. In spite of these constraints, the study provides interesting information which can be helpful in planning maternal and child health services at a district level. In conclusion, as compared to non-diabetics, gestational diabetics have higher maternal and neonatal complications. With the availability of early prenatal detection and good antenatal care provided to these patients, one can expect to bring a perceptible improvement in the outcome of these pregnancies. The observation and quantification of maternal outcomes with GDM are necessary so that appropriate measures can be taken to reduce complications during pregnancy, delivery, and the neonatal period.

References

- 1.Sicree R, Shaw J, Zimmet P. Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in India. In: Gan D, editor. Diabetes atlas. Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2006. pp. 15–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/EN/Section1243/Section1382/Section1386/Section1898_9438.htm. Accessed 10 Mar 2008.

- 3.World Health Organization, Regional Office for South East Asia. Health Situation in South East Asia Region (1998–2000), Regional office for SEAR New Delhi. 2002. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/Health_Situation_book.pdf. [cited in 2002]. Accessed Mar 2010.

- 4.Ahuja MM, Sivaji L, Garg VK, Mitroo P. Prevalence of diabetes in northern India (Delhi area) Horn Metab Res. 1974;4:321. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1094024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta OP, Joshi MH, Dave SK. Prevalence of diabetes in India. Adv Metab Disord. 1978;9:147–165. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-027309-6.50013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langer O, Yogev Y, Most O, et al. Gestational diabetes: the consequences of not treating. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merlob P, Hod M. Short-term implications: the neonate. In: Hod M, Jovanovic L, Di Renzo GC, de Leiva A, Langer O, editors. Textbook of diabetes and pregnancy. 1. London: Martin Dunitz; 2003. pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee S, Ghosh US, Banerjee D. Effect of tight glycemic control on fetal complications in diabetic pregnancies. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shefali AK, Kavitha M, Deepa R, Mohan V. Pregnancy outcome pregestational and gestational diabetic women in comparison to nondiabetic women—a prospective study in Asian Indian mothers (CURES-35) J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:613–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seshiah V, Balaji V, Balaji MS, Sanjeevi CB, Green A. Gestational diabetes mellitus in India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:707–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of diabetes mellitus Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183–1197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metzger BE, Coustan DR. Proceedings of the fourth international workshop-conference on gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(Suppl. 2):B1–B167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen DM, Sorensen B, Feilberg-Jorgensen N, Westergaardt JG, Beck-Neilsen H. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in 143 Danish women with gestational diabetes mellitus and 143 controls with a similar risk profile. Diabet Med. 2000;17:281–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaffir JA, Lockwood CJ, Lapinski R, Yoon L, Alvarez M. Incidence of pregnancy-induced hypertension among gestational diabetics. Am J Perinatol. 1995;12:252–254. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nachum Z, Ben-Shlomo I, Weiner E, Shalev E. Twice daily versus four times daily insulin dose regimens for diabetes in pregnancy: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 1999;319:1223–1227. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7219.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naylor CD, Sermer M, Chen E, Farine D. Selective screening for gestational diabetes mellitus. Toronto Tri-Hospital Gestational Diabetes Project Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1591–1596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vivet-Lefébure A, Roman H, Robillard PY, Laffitte A, Hulsey TC, Camp G, et al. Obstetrical and neonatal outcomes of gestational diabetes mellitus at Reunion Island (France) Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2007;35(6):530–535. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kale SD, Kulkarni SR, Lubree HG, Meenakumari K, Deshpande VV, Rege SS, et al. Characteristics of gestational diabetic mothers and their babies in an Indian diabetes clinic. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:857–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boriboonhirunsarn D, Talungjit P, Sunsaneevithayakul P, Sirisomboon R. Adverse pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes mellitus. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89(Suppl 4):S23–S28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong X, Saunders LD, Wang FL, Demianczuk NN. Gestational diabetes mellitus: prevalence, risk factors, maternal and infant outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;75(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00496-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van W, Wootten BS, Turner RE. The prevalence of macrosomia in neonates of gestational diabetic mothers analysis of risk factors. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(9):A32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magee MS, Walden CE, Benedetti TJ, Knopp RH. Influence of diagnostic criteria on the incidence of gestational diabetes and perinatal mortality. J Am Med Assoc. 1993;269(5):609–615. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03500050087031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]