Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common autoimmune rheumatic disease. It is characterized by persistent joint inflammation, resulting in loss of joint function, morbidity and premature mortality. The presence of antibodies against citrullinated proteins is a characteristic feature of RA and up to 70% of RA patients are anticitrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) positive. ACPA responses have been widely studied and are suggested to be heterogeneous, favoring antibody cross-reactivity to citrullinated proteins. In this study, we examined factors that may influence cross-reactivity between a commercial human anticitrullinated fibrinogen monoclonal antibody and a citrullinated peptide. Using a citrullinated profilaggrin sequence (HQCHQEST- Cit-GRSRGRCGRSGS) as template, cyclic and linear truncated peptide versions were tested for reactivity to the monoclonal antibody. Factors such as structure, peptide length and flanking amino acids were found to have a notable impact on antibody cross-reactivity. The results achieved contribute to the understanding of the interactions between citrullinated peptides and ACPA, which may aid in the development of improved diagnostics of ACPA.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, epitope, citrulline, solid-phase peptide synthesis, monoclonal antibody

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disease of unknown etiology, which is characterized by joint destruction and chronic disability. RA is the most prevalent chronic inflammatory arthritis affecting 1–2% of adults worldwide, with an incidence of 20–50 per 100,000 persons per year.1 Cohort studies suggest that the prevalence peaks at 65–74 years.2

Besides persistent synovitis and systemic inflammation, autoantibodies are a classical feature of RA.3 Antibodies to citrullinated proteins are among the most specific described in RA and are believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease.4–8 These antibodies were originally identified by Schellekens et al.,9 who described specific antibody reactivity to a profilaggrin peptide containing the modified amino acid citrulline. The post-translational generation of citrulline, referred to as citrullination or deimination, is a modification of the side chain of arginine, where the guanidino group is replaced by an ureido group. Thus, citrullination leads to neutralization of the positively charged arginine, which alters the properties of proteins, including overall charge and isoelectric point, as well as the ionic and hydrogen bond forming abilities of the proteins.4, 10

Antibodies specific for citrullinated proteins recognize a variety of citrullinated autoantigens, including α-enolase, fibrinogen, type II collagen, and vimentin, and are collectively identified as anticitrullinated peptide/protein antibodies (ACPA).11–15 These ACPA responses, primarily characterized by IgG1 and IgG4 subtypes (99 and 98% of ACPA-positive RA patient sera, respectively), have been found to be present up to years before disease onset and to be highly specific (98%) and sensitive (up to 80%) for RA.16–21 Thus, APCA are used as a supplement to clinical diagnosis of RA.20 The most frequently used peptide-based immunoassay for ACPA detection is based on cyclic citrullinated peptides (CCP). CCP antibodies have been demonstrated to be sensitive and highly specific for RA;22 hence, anti-CCP/ACPA have been included as a new serologic criterion in the 2010 RA classification criteria.23, 24 Besides CCP assays, new peptide-based diagnostic assays for detection of ACPA have been generated, such as chimeric peptide assays based on fibrin and filaggrin sequences and a mutated version of vimentin using Cit-Gly sequences.25–27 In these peptide-based immunoassays, cyclic peptide structures are often preferred, as antigenic recognition can be significantly improved by restricting peptide mobility, even though the direct effect of cyclization seems to be sequence dependent.21, 25, 28

Several factors have been found to be essential for ACPA recognition. Especially the length of the antigenic binding region has been found to be essential for antibody reactivity.9 In addition, amino acids surrounding citrulline have been shown to be essential for ACPA reactivity, and especially antigen binding regions containing citrulline residues flanked by neutral and relatively flexible structures, such as glycine and serine,9, 15, 25, 29, 30 often show increased reactivity compared to peptides containing strongly charged residues or residues of fixed structure such as proline, as these contribute to a rigid structural conformation. In addition, structural homology of the amino acid residues surrounding citrulline has been described to be essential as well.31 These findings were primarily based on cross-reactivity described between a fibrinogen peptide and a filaggrin-derived peptide antibody. Most important, these results indicated that ACPA responses against several citrullinated autoantigens coexist in RA patients,31 which is in accordance to studies describing that ACPA-positive RA patient sera recognize a number of citrullinated antigen binding regions, indicating cross-reactive ACPA responses.32 Additional analyses of ACPA responses to citrullinated proteins have confirmed that ACPA indeed are cross-reactive, but apparently this cross-reactivity is not complete, as distinct noncross-reactive ACPA responses have been detected as well.25, 33 This cross-reactivity, prevailing in the majority of ACPA responses, identifying multiple citrullinated targets, complicates the identification of the antigen(s) responsible for the initiation of the ACPA response. Moreover, this is further complicated as studies describing ACPA responses indicate that these change over time.16, 34 This is, according to Ioan-Facsinay et al.,33 a matter of continuous activation of naïve B cells, hence introducing new reactivities in the ACPA response.

In this study, we examined the cross-reactivity of a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against citrullinated fibrinogen (Cit mAb) to a citrullinated profilaggrin peptide (HQCHQEST-Cit-GRSRGRCGRSGS), with special emphasis on peptide structure and amino acid composition. The profilaggrin peptide was selected for analysis, as this peptide originally was applied for ACPA diagnostics.21

Results

Analysis of linear and cyclic citrullinated peptides

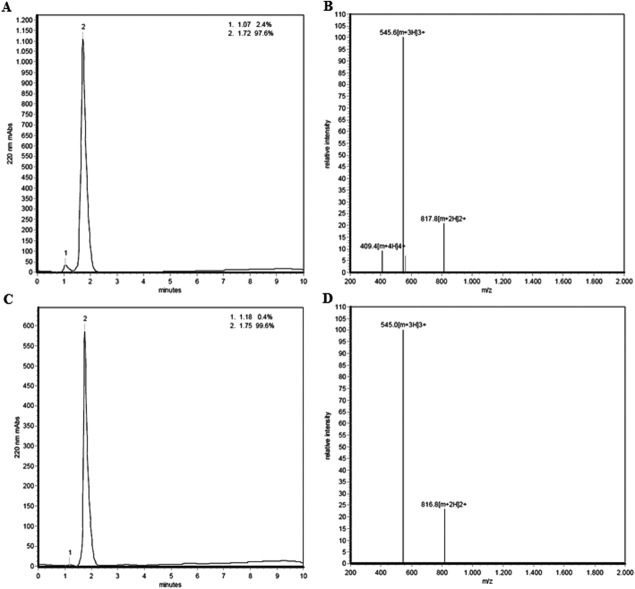

To verify the identity of the linear citrullinated peptides (LCPs) and CCPs used in this study, the peptides were characterized by HPLC and mass spectrometry.

Figure 1 is a representative analysis of the linear and cyclic peptides using LCPb (CHQEST-Cit-GRSRGRC) and CCPb as examples. As illustrated in Figure 1(A,C), LCPb and CCPb were highly purified (97.6 and 99.6%, respectively), which was demonstrated by single distinct peaks in the HPLC chromatograms. When analyzing the peptides by mass spectrometry [Fig. 1(B,D)] LCPb was identified with a relative [M+2H]2+molecular mass of 817.8, yielding a total mass of 1633.6 (calculated 1633.8), while CCPb yielded a relative [M+2H]2+molecular mass of 816.8, with a total mass of 1631.6 (calculated: 1631.8). A difference of 2 in the molecular mass was found when comparing the molecular masses of CCPb to LCPb, conforming to the presence of a disulfide bond in CCPb and the loss of two hydrogen atoms. Similar results were obtained for the remaining LCPs and CCPs (results not shown). Peptide purities, calculated and identified masses of the remaining peptides are listed in Table I. As seen, all the applied peptides were highly purified, as the majority of the peptide purities varied between 96 and 100%.

Figure 1.

Quality control of LCPb and CCPb verified by HPLC and mass spectrometry. LCPb was analyzed by HPLC (A) and mass spectrometry (B). CCPb was examined by HPLC (C) and mass spectrometry (D).

Table I.

Cyclic and Linear Peptides Applied for Reactivity Screening to Cit mAb

| Peptide | Amino acid sequence | Peptide purity in % | Peptide mass calculated (identified) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCP/CCPa | HQCHQEST-X-GRSRGRCGRSGS | 96.2/99.5 | 2343.5 (2343.0)/2341.5 (2341.2) |

| LCP/CCPb | CHQEST-X-GRSRGRC | 97.6/99.6 | 1633.8 (1633.6)/1631.8 (1631.6) |

| LCP/CCPc | CQEST-X-GRSRGC | 100/100 | 1340.5 (1340.2)/1338.5 (1339.2) |

| LCP/CCPd | CEST-X-GRSRC | 99.4/98.9 | 1155.3 (1155.0)/1153.3 (1153.0) |

| LCP/CCPe | CST-X-GRSC | 99.1/94.5 | 870.0 (870.4)/868.0 (867.4) |

| LCP/CCPf | CST-X-GRC | 99.7/98.2 | 782.9 (783.3)/780.9 (780.5) |

| LCP/CCPg | HQCHQEST-R-GRSRGRCGRSGS | 88.7/99.7 | 2342.5 (2342.5)/2340.5 (2340.0) |

| [R2,H13]CCPb | CRQEST-X-GRSRGHC | 99 | 1631.8 (1631.7) |

| [K2,K13]CCPb | CKQEST-X-GRSRGKC | 98 | 1594.8 (1594.8) |

| [A2,A13]CCPb | CAQEST-X-GRSRGAC | 84.5 | 1480.6 (1480.8) |

| [A6,A8]LCPb | CHQESA-X-ARSRGRC | 100 | 1617.8 (1617.3) |

| [A5,A9]LCPb | CHQEAT-X-GASRGRC | 89.9 | 1532.7 (1532.4) |

| [A4,A10]LCPb | CHQAST-X-GRARGRC | 96.3 | 1559.8 (1559.4) |

| [A2]LCPb | CAQEST-X-GRSRGRC | 83.3 | 1567.7 (1567.8) |

| [A3]LCPb | CHAEST-X-GRSRGRC | 99.3 | 1576.7 (1576.2) |

| [A4]LCPb | CHQAST-X-GRSRGRC | 100 | 1575.8 (1575.3) |

| [A5]LCPb | CHQEAT-X-GRSRGRC | 100 | 1617.8 (1617.3) |

| [A6]LCPb | CHQESA-X-GRSRGRC | 100 | 1603.8 (1603.8) |

| [A7]LCPb | CHQEST-A-GRSRGRC | 98.5 | 1547.7 (1547.4) |

| [A8]LCPb | CHQEST-X-ARSRGRC | 86.2 | 1647.8 (1647.6) |

| [A9]LCPb | CHQEST-X-GASRGRC | 96.2 | 1548.7 (1548.5) |

| [A10]LCPb | CHQEST-X-GRARGRC | 100 | 1617.8 (1617.6) |

| [A11]LCPb | CHQEST-X-GRSAGRC | 97.2 | 1548.7 (1548.3) |

| [A12]LCPb | CHQEST-X-GRSRARC | 100 | 1647.8 (1647.6) |

| [A13]LCPb | CHQEST-X-GRSRGAC | 99.3 | 1548.7 (1548.0) |

| [G8]LCPb | SHQEST-X-GRSRGRS | 95.8 | 1601.7 (1601.7) |

| [P8]LCPb | SHQEST-X-PRSRGRS | 100 | 1641.7 (1641.3) |

| [E8]LCPb | SHQEST-X-ERSRGRS | 90 | 1673.3 (1673.4) |

| [W8]LCPb | SHQEST-X-WRSRGRS | 89.3 | 1730.8 (1730.4) |

| [H8]LCPb | SHQEST-X-HRSRGRS | 88.2 | 1681.7 (1681.5) |

| [V8]LCPb | SHQEST-X-VRSRGRS | 100 | 1643.7 (1643.2) |

| [S8]LCPb | SHQEST-X-SRSRGRS | 98.5 | 1631.7 (1630.8) |

“X” represents the citrulline residue.

Reactivity of the monoclonal antibody to citrullinated peptides

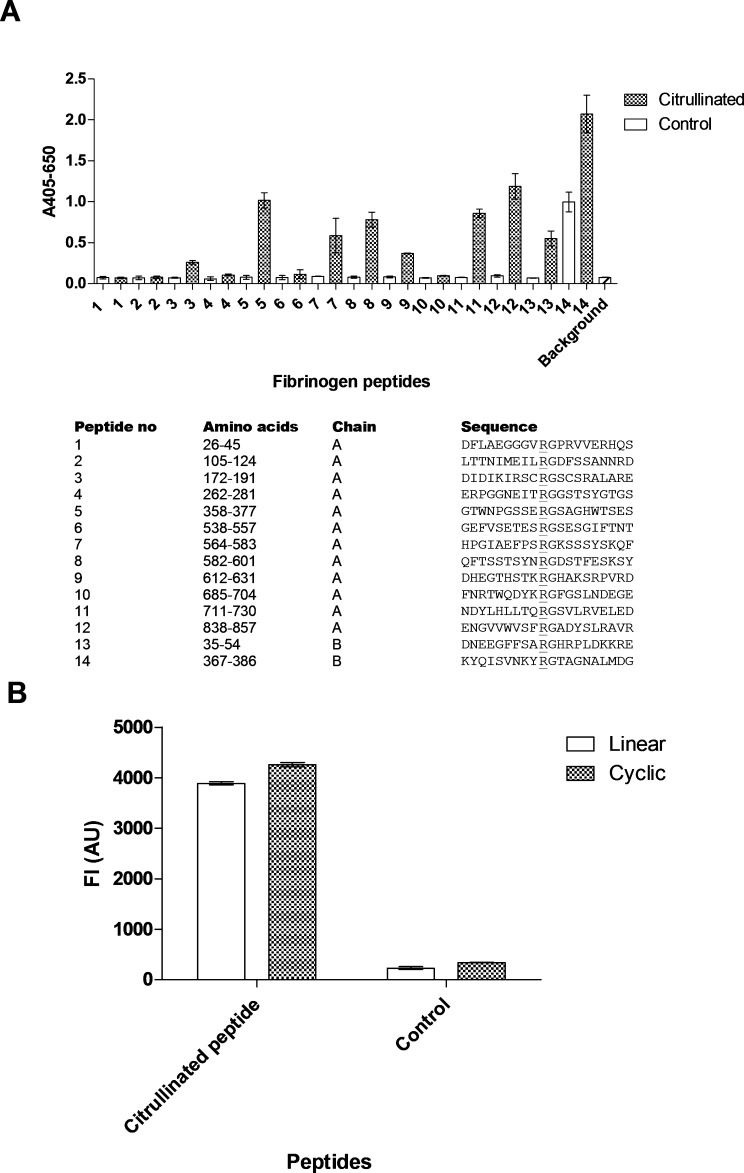

To verify the reactivity of the Cit mAb to citrullinated fibrinogen, modified enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed. Selected peptides of the α- and β-chain containing arg/cit residues central in the peptides were applied.

As illustrated in Figure 2(A), antibody reactivity was found to ∼50% of the citrullinated resin-bound peptides, verifying the reactivity of the Cit mAb to citrullinated fibrinogen.

Figure 2.

Reactivity of Cit mAb to fibrinogen peptides, LCPa and CCPa analyzed by modified ELISA and Luminex immunoassay, respectively. (A) Reactivity to fibrinogen peptides. Citrullinated peptides are represented by shaded bars, while remaining arginine containing peptides function as negative controls. (B) Reactivity to LCPa and CCPa. Noncitrullinated peptides (LCPg and CCPg) were used as negative controls.

In addition, the cross-reactivity of the Cit mAb was examined to a linear (LCPa) and cyclic (CCPa) peptide (HQCHQEST-Cit-GRSRGRCGRSGS) by ELISA.

As illustrated in Figure 2(B), the Cit mAb only showed reactivity toward the citrullinated peptides, indicating that the interaction is specific. No significant difference in antibody reactivity was found for LCPa and CCPa, showing that the Cit mAb recognized LCPa and CCPa to the same extent.

Reactivity of the monoclonal antibody to truncated cyclic and linear citrullinated peptides

To examine whether peptide length and structure influence antibody recognition, truncated peptide versions of LCPa and CCPa were generated (Table I). Antibody reactivity to the truncated LCPs and CCPs variants was examined by Luminex immunoassay.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the linear peptides were significantly better recognized compared to their cyclic peptide versions (P = 0.025). As seen, the Cit mAb recognized two cyclic peptides and five linear peptides, corresponding to CCPa-CCPb and LCPa-e, respectively. No reactivity to the peptides CCPc-f and LCPf was observed, even though citrulline was present in these peptides, indicating that other factors besides the mere presence of citrulline are essential for antibody recognition. When comparing antibody reactivity to the corresponding cyclic and linear peptide versions, no significant difference was found (e.g., when comparing reactivity to CCPa and LCPa, CCPb and LCPb). Profound differences were found for the remaining peptide versions (LCPc-LCPe vs. CCPc-CCPe), as neither of the cyclic peptides were recognized by the Cit mAb, suggesting that the peptide structure is essential for antibody reactivity.

Figure 3.

Reactivity of Cit mAb to truncated linear and cyclic citrullinated peptides analyzed by Luminex immunoassay. The citrullinated peptide LCPa/CCPa was used as template. Noncitrullinated peptides LCPg and CCPg were used as negative controls.

When comparing antibody reactivity to the linear peptides, LCPa-LCPe the reactivity was found to decrease with decreasing number of amino acids present in the respective peptide; thus, LCPa and LCPb showed the highest reactivity, whereas LCPe showed the lowest antibody reactivity, suggesting that the peptide length is essential for antibody reactivity as well.

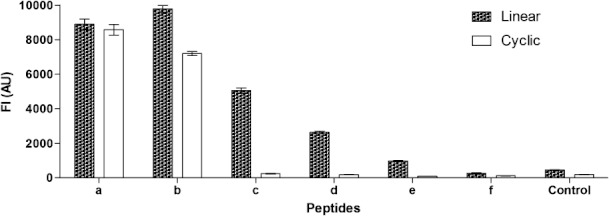

Importance of peptide structure for monoclonal antibody recognition

The results above indicated that the peptide structure influenced antibody reactivity, as the peptides CCPc-CCPe were not recognized by the Cit mAb. To determine whether the number of amino acids in the cyclic structure was essential for antibody reactivity, substitution experiments were conducted. Using CCPc as template, different amino acids were added to the terminal ends (position 2 and 13), generating new CCPb analogs (Table I). Three versions were generated, one contained alanines in position 2 and 13 ([A2,A13]CCPb), one contained lysines ([K2,K13]CCPb) and in the last version were the amino acids histidine and arginine in position 2 and 13 exchanged ([R2,H13]CCPb). Antibody reactivity to the substituted peptides was determined by Luminex immunoassay.

As illustrated in Figure 4, the CCPb analogs showed notably increased reactivity compared to CCPc. No significant difference in antibody reactivity was observed when comparing CCPb with [R2,H13]CCPb and [K2,K13]CCPb, illustrating that addition of amino acids in the terminal ends restores antibody reactivity. Antibody reactivity to [A2,A13]CCPb was observed as well; however, it was found to be significantly reduced compared to the CCPb control (P = 0.0034). These results show that the number of amino acids in the cyclic structure directly influence antibody reactivity, underlining the importance of proper peptide structures for epitope presentation.

Figure 4.

Reactivity of Cit mAb to CCPb analogs analyzed by Luminex immunoassay. The noncitrullinated peptide CCPg was used as control.

Relevance of single amino acids for antibody reactivity

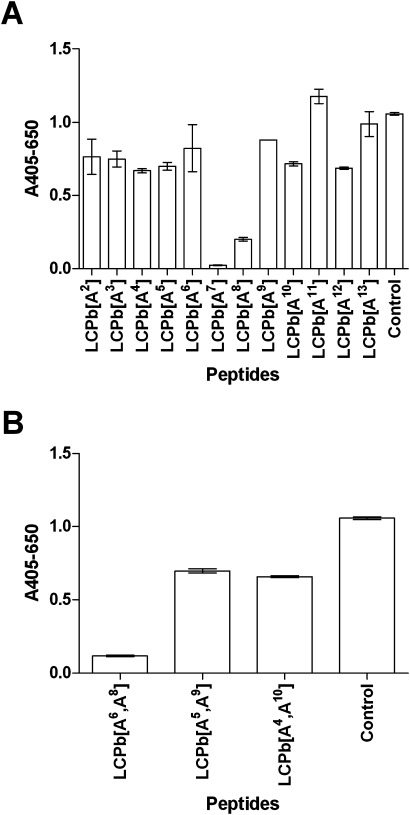

To examine the importance of the individual amino acids for antibody reactivity, alanine scanning was conducted using LCPb as template, as this was the shortest peptide yielding maximal antibody reactivity. Substituting each amino acid in LCPb with alanine (Table I), the reactivity to the alanine-substituted peptides was determined by ELISA.

As illustrated in Figure 5(A), the most significant reduction in reactivity was observed when citrulline was replaced by alanine ([A7]LCPb), where an ∼100% reduction was found compared to the control LCPb(P = 0.0001). In addition, a significant reduction in reactivity of ∼80% was found when the glycine C-terminal to citrulline ([A8]LCPb) was substituted (P = 0.0001). When testing antibody reactivity to the substituted peptides [A3]LCPb-[A5]LCPb and [A9]LCPb-[A10]LCPb, [A12]LCPb a significant reduction in antibody reactivity of ∼20–35% was found (P < 0.05), while antibody reactivity to the remaining substituted peptides, [A2]LCPb, [A6]LCPb, [A11]LCPb, and [A13]LCPb, not was found to be significant. These results indicated that citrulline and the Cit-Gly motif was most important for antibody recognition.

Figure 5.

Reactivity of Cit mAb to alanine-substituted LCPb peptides analyzed by ELISA. LCPb was used as control. (A) Reactivity to single alanine-substituted peptides. Letters illustrated indicate amino acids substituted, starting from the N-terminal end. (B) Reactivity to double alanine-substituted peptides.

Next, multiple alanine-substituted peptides were tested for antibody reactivity, as the amino acids in the first, second, and third flanking positions previously have been suggested to be of central importance to antibody reactivity. Three substituted peptides, ([A6,A8]LCPb, [A5,A9]LCPb, and [A4,A10]LCPb) were generated, where two amino acids (one N-terminally and one C-terminally of citrulline), in the first three flanking positions were substituted with alanine residues. The multiple alanine-substituted peptides were tested for antibody reactivity by ELISA.

As illustrated in Figure 5(B), antibody reactivity to [A6,A8]LCPb was significantly reduced by ∼90% compared to the control LCPb(P < 0.0001), whereas antibody reactivity to the remaining two substituted peptides, [A5,A9]LCPb, [A4,A10]LCPb, was significantly reduced by ∼40% compared to the control (P < 0.0011). These results indicate that the amino acids in the two flanking positions [S6,G8] of citrulline were found to be most important for antibody reactivity. In general, when comparing antibody reactivity levels between the double-substituted peptides, [A6,A8]LCPb, [A5,A9]LCPb, [A4,A10]LCPb, and single-substituted peptides, [A4]LCPb-[A10]LCPb, no significant difference in reactivity levels were observed, indicating that individual amino acids and not the N- and C-terminal amino acid combinations found in first, second, and third flanking positions of citrulline, respectively, are essential for reactivity. Likewise, the pronounced low reactivity to [A6,A8]LCPb seems to be due to the absence of glycine and not necessarily the absence of serine. These results confirm that the Cit-Gly motif is important for reactivity.

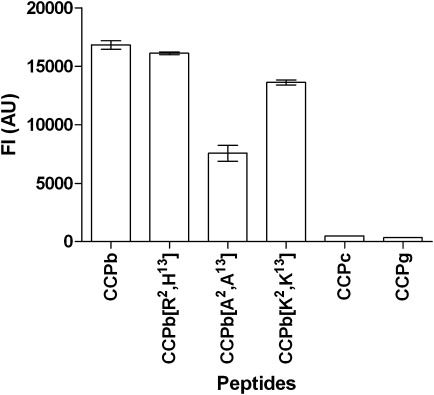

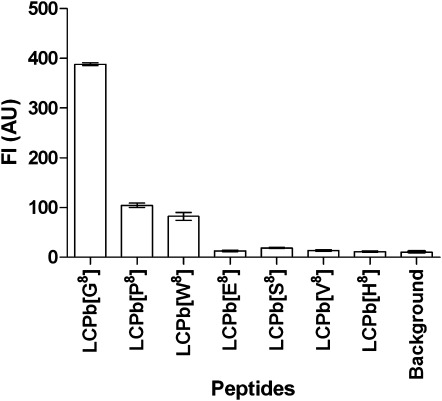

Screening of substituted peptides to examine relevance of the glycine residue C-terminal to citrulline

To examine the dependency of the glycine residue C-terminally next to citrulline, substituted peptide analogs of LCPb, containing varying amino acids in position 8 (Table I), were tested for antibody reactivity by Luminex immunoassay. Amino acids selected for substitution were based on size, charge, and hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity; thus, serine, proline, glutamic acid, histidine, tryptophan and valine were selected for substitution analysis.

As illustrated in Figure 6, maximal antibody reactivity was obtained to the control [G8]LCPb. Of the substituted peptide analogs, only the peptides containing proline ([P8]LCPb) and tryptophan ([W8]LCPb) were recognized by the Cit mAb, albeit with a significantly reduced antibody reactivity (P < 0.0004) of ∼75–80% compared to the control [G8]LCPb. In addition, substituted peptides containing histidine, glutamic acid, serine, and valine ([H8]LCPb, [E8]LCPb, [S8]LCPb, and [V8]LCPb) were not recognized by the Cit mAb, indicating that only a few amino acids are tolerated in the C-terminal position next to citrulline and that optimal antibody reactivity is found when glycine is present in this position.

Figure 6.

Reactivity of Cit mAb to substituted LCPb peptides analyzed by Luminex immunoassay. Glycine in position 8 of the template peptide LCPb was substituted with proline, serine, tryptophan, valine, serine, and histidine. LCPb was used as control. Resins without peptides were used for background determination.

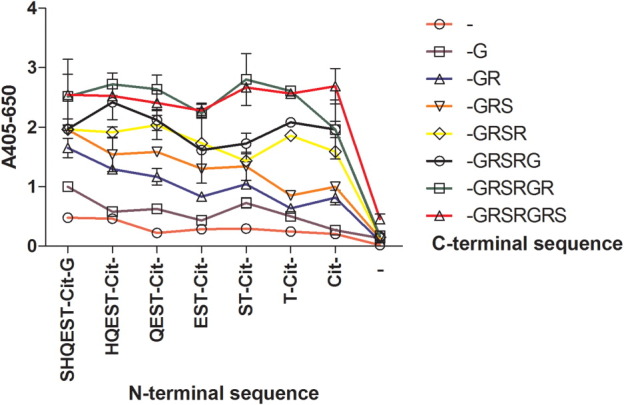

Reactivity of the monoclonal antibody to truncated epitope candidates

To identify the cross-reactive region of the LCPb peptide recognized by the Cit mAb, truncated resin-bound LCPb variants were generated and tested for antibody reactivity by modified ELISA. LCPb was used as template for generation of the truncated peptide analogs, except for the terminal cysteines, which had been replaced with serines, as found in the original sequence.

As illustrated in Figure 7, the Cit mAb did not show notable reactivity to peptides omitting citrulline (C-terminal peptide truncation series G-GRSRGRS, starting points illustrated by varying colors). However, as amino acids were added to the N- and C-terminal ends, antibody reactivity was found to increase. Reactivity to the N-terminal-truncated peptides (designated as the left side of citrulline) was found to increase with increasing number of amino acids in the peptide; this was especially profound for truncation series originating from peptide truncation series G-GRSR. Antibody reactivity to the C-terminal truncated peptides was found to depend on peptide length as well. This was especially profound for peptide truncation series (Cit-GR to Cit-GRSRG), which contained a limited number of amino acids C-terminal to citrulline, indicating that especially the amino acids on the C-terminal side of citrulline were essential for reactivity. However, antibody reactivity was similar for the C-terminal truncation series Cit-GRSRGR and Cit-GRSRGRS, indicating that the cross-reactive region is found within truncation series -Cit-GRSRGR. The dependency of amino acids C-terminal of citrulline for antibody reactivity was especially pronounced when comparing antibody reactivity of the resin-bound peptide SHQEST-Cit (Absorbance ∼1) to the peptide Cit-GRSRGRS (Absorbance ∼2.6), indicating that the reactive region is not located in the center of the peptide. This is in agreement with that the peptide Cit-GRSRGRS yielded the highest absorbance (∼2.6) compared to the central peptide QEST-Cit-GRSR obtaining an absorbance of approximately 2.0. Based on these results, the cross-reactive region was identified as the peptide sequence ST-Cit-GRSRGR.

Figure 7.

Reactivity of Cit mAb to N- and C-terminally truncated versions of LCPb analyzed by modified ELISA. SHQEST-Cit-GRSRGRS was used as template. N-Terminal truncations were generated prior to the citrulline residue and forth, being represented by the x-axis, read from right to left, with blank resin to the right being represented by (−) and the S to the far left, represented by SHQEST-Cit-. C-Terminal truncations were generated from the C-terminal serine residue and to the citrulline residue, being represented by the varying dots on the y-axis, ranging from blank resin to -GRSRGRS.

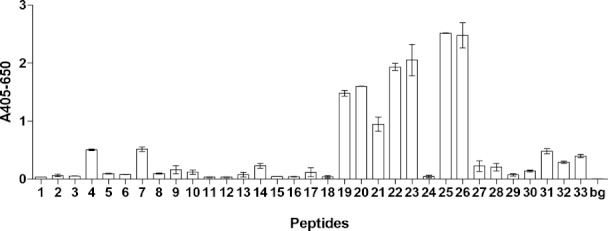

Screening of RA33 peptides to verify Cit-Gly dependency

To verify that antibody reactivity of the Cit mAb is in fact dependent on the presence of the Cit-Gly motif, overlapping citrullinated 20mer peptides spanning the human RA33 protein, rich in potential Cit-Gly motifs, were screened for antibody reactivity.

As illustrated in Figure 8, distinct antibody reactivity was found to no 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25 and 26. All of these reactive peptides contained Cit-Gly motifs. No other amino acid combinations containing citrulline was found in these recognized peptides, confirming that the Cit-Gly motif is of utmost importance for Cit mAb reactivity. The amino acid N-terminal to citrulline in these peptides was found to vary, thus, serine, phenylalanine and glycine were found in this position. However, varying amino acids in this position did not seem to influence antibody reactivity. These results support that the Cit mAb indeed depend on a Cit-Gly motif for distinct antibody reactivity. Interestingly, peptide 26, showing the highest antibody reactivity contained 70% glycine residues, indicating that backbone interactions are essential for antibody reactivity.

Figure 8.

Rectivity of Cit mAb to overlapping peptides spanning the human RA33 protein analyzed by modified ELISA. Sequences are listed in Supporting Information. The difference between nonreacting and reacting peptides numbers 19, 20, 23, 22, 25, and 26 is higher than three times the maximal standard deviation. Resins without peptides were used for background determination.

Screening of glycine-substituted peptides to verify backbone reactivity

Finally, reactivity of the Cit mAb to Cit-Gly containing peptides was demonstrated by ELISA. Using resin-bound peptides containing 13 glycine residues, two substituted peptides were generated containing either citrulline or homocitrulline residue in the central position of the peptides.

As illustrated in Figure 9, significant antibody reactivity was obtained to the citrulline substituted peptide compared to the noncitrullinated glycine control (P = 0.0020). In addition, no notable antibody reactivity was obtained to the homocitrullinated peptide compared to the glycine control, indicating that Cit mAb antibody reactivity depends on Cit-Gly and backbone for reactivity.

Figure 9.

Reactivity of Cit mAb to citrulline- and homocitrulline-substituted glycine peptides analyzed by modified ELISA. The peptide GGGGGGGGGGGGGG was used as negative control. Resins without peptides were used for background determination.

Discussion

Results obtained in this study define the cross-reactivity of the human anticitrullinated fibrinogen mAb to the profilaggrin peptide HQCHQEST-Cit-GRSRGRCGRSGS and various peptide analogs. Especially the Cit-Gly motif, peptide length and peptide structure had notable impact on Cit mAb cross-reactivity.

Preliminary analyses indicated that the mere presence of citrulline was insufficient to obtain antibody reactivity, as the Cit mAb did not show antibody reactivity to all of the citrulline-containing peptides applied in this study, confirming that other factors are essential for reactivity as well.

Besides the presence of citrulline, the peptide structure was found to influence antibody reactivity. When comparing antibody reactivity to linear and cyclic variants (Fig. 3), only two cyclic (CCPa-b) and five linear (LCPa-e) peptide variants were recognized. One reason why the relatively small CCPs, CCPc-CCPe, were not recognized by the Cit mAb, could be that the relatively small cyclic peptides become locked in their structures, making the peptides less flexible. As a result, the peptides become sterically hindered in obtaining recognizable peptide structures. By adding random amino acids to the cyclic structure and making the peptides less sterically hindered and more flexible, the cyclic peptides are recognized by the Cit mAb, as illustrated in Figure 4. As seen, addition of amino acids to the terminal ends of CCPc, generating new CCPb analogs, notably restored antibody reactivity when compared to CCPc, illustrating that peptide structure influences antibody reactivity.

Based on previous studies, CCPs are widely applied in the diagnosis of RA.21, 25, 26 However, as illustrated in this study, the antibody reactivity to cyclic peptides may vary significantly, indicating that cyclic structures are not natural antigenic epitopes. Thus, all cyclic peptide structures are not necessarily good candidates for diagnostic purposes. Cyclic peptide versions were originally used, as short peptides usually do not have a preferential conformation in solution, but can sometimes adopt moderately stabilized secondary structures.35 In addition, analysis of antibody–peptide complexes has shown that peptides in epitopes often adopt a β-turn structure,36 a motif which frequently is encountered within the filaggrin sequence.37 Thus, cyclization was conducted in order to force the peptide to adopt a β-hairpin conformation, as cysteine-bridged cyclic peptides have been shown to mimic the β-turn structure of the antigenic epitope, increasing antibody reactivity.38 Nevertheless, our results could not confirm that cyclic structures increased antibody reactivity of the Cit mAb compared to the linear versions. This knowledge may be of profound importance for the diagnostic value of human ACPA levels, as these results indicate that linear peptides may be equally applicable in ACPA diagnostics.

Various results on antibody recognition have been obtained when using cyclic peptides,21, 25, 26, 28, 30 indicating that the effect of cyclization may be peptide dependent. Thus, we speculate that the effect of constrained peptides locked in cyclic structures only is favorable in relation to antibody binding, if the peptides may be presented in a way that resembles or easily adopt the conformational features of the antigenic site within the native protein.

Besides peptide structure and the presence of citrulline, a minimum peptide length was found to be necessary for antibody recognition, as neither LCPf nor CCPf was recognized by the Cit mAb (Fig. 3). The fact that LCPf was the only linear peptide not to be recognized by the Cit mAb may be due to structural restraints, as small linear peptides tend to be less flexible, thereby reducing their abilities for proper antigen presentation. The fact that peptide length influenced antibody reactivity was further supported when screening N- and C-terminal truncated peptides (Fig. 7), as the amino acid sequence necessary for optimal antibody reactivity of the Cit mAb, was found to be nine amino acids long (Fig. 8). However, only the Cit-Gly motif was found to be essential for antibody reactivity (Fig. 5). As illustrated in Figures 5 and 6, it was found that substitution of citrulline and glycine notably reduced antibody reactivity. These results were confirmed when screening citrullinated RA33 peptides for reactivity (Fig. 8), as only Cit-Gly-containing peptides were recognized by the Cit mAb. These findings are in accordance to several studies illustrating that Cit-Gly-containing peptides have high sensitivities for RA diagnostics.9, 25, 29, 30 Nevertheless, the presence of Cit-Gly alone was not sufficient to obtain reactivity, as no antibody reactivity to the isolated Cit-Gly peptide was found (Fig. 7), indicating that the Cit-Gly motif in combination with proper peptide structure and backbone interactions is essential for antibody reactivity. These findings were confirmed in Figure 9, as the Cit mAb showed distinct reactivity to the GGGGGG-Cit-GGGGGG peptide. Moreover, no reactivity was obtained to the homocitrullinated glycine peptide. Homocitrulline highly resembles citrulline, as homocitrulline is one methylene group longer, but similar in nature.39 These findings are in accordance to the literature, describing that antibodies to homocitrulline are noncross-reactive.40

To our knowledge, this study is the first to illustrate cross-reactivity of the Cit mAb to a glycine backbone containing a single citrulline, confirming that this mAb (and probably related antibodies) indeed is cross-reactive. Hence, these findings will be used for comparison in future studies of RA patient sera as results achieved are in accordance to earlier studies9, 29 describing ACPA reactivity to LCPa/CCPa, indicating that our results may relate to ACPA responses of RA patient sera. This assumption is further supported as the CCPa originally was applied in the diagnostic of ACPA and current results were obtained applying a human monoclonal antibody, which originally was isolated from a human RA patient.

In recent years, cross-reactivity in ACPA responses has received much attention, which markedly has increased the knowledge in this field.25, 26, 30, 32, 33 The fact that considerable cross-reactivity between ACPA recognizing different antigens within a single patient exists, notably complicates identification of “true” antigenic structures and the involvement of citrullinated antigens in the pathophysiology of RA, as extensive characterization of ACPA responses to a single antigen might be a proxy for recognition of other citrullinated antigens. Despite the pronounced cross-reactivity prevailing in these ACPA responses, our results and current knowledge indicate that only limited side chain-specific reactivity in combination with backbone interactions is necessary to obtain reactivity with these antibodies. Thus, based on high cross-reactivity, results achieved in this study indicate that any sequence containing Cit-Gly in a properly folded peptide structure in theory could be an antigen-binding region, complicating the identification of citrullinated autoantigens in RA. Accordingly, one would expect that the number of proposed autoantigens in RA will increase, which is consistent with the literature, describing recently identified citrullinated autoantigens in RA.41 To confirm that cross-reactive ACPA responses are prevailing, a definite proof for the origin of the heterogeneous ACPA responses and identification of the “true” autoantigen may be to conduct a careful analysis of the ACPA producing B cells.

In relation to identification of citrullinated peptides, the results achieved indicate that linear citrullinated peptides indeed are applicable for diagnostic purposes. Even though the currently applied CCP2 ELISA detection kit is based on cyclic peptide versions, our studies with a monoclonal antibody do not confirm that increased reactivity is obtained when using cyclic peptides. This is further supported by the fact that not all assays designed for detection of ACPA are based on cyclic peptides.20 In regard to presentation of the cross-reactive region within the peptide structures, the influence of antigen presentation should be elucidated, to improve the usefulness of peptide-based diagnostics.

In conclusion, these studies may provide useful information on the nature of the antibody-peptide interactions but most important on the antigenic determinants responsible for the specific occurrence of ACPA in RA sera.

Materials and Methods

Materials

2-Chloro-trityl-resins were from Novabiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). Tentagel S RAM resin was from RAPP Polymere (Tubingen, Germany). 1-Hydroxy-7-aza-benzotriazole (HOAt) was from GL Biochem (Shanghai). N,N′-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC), piperidine (PIP), 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc)-protected amino acids, and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) were from Iris Biotech (Marktredwitz, Germany). Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), thioanisole (THIO), alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-human IgG, para-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP), 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid, bovine serum albumin (BSA) and ether were from Sigma Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Triisopropylsilane (TIS) was from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland). α-Cyano-p-hydroxycinnamic acid and peptide calibration were from Bruker Daltonik (Bremen, Germany). Tween 20 and NaN3 were from Merck (Hohenbrunn, Germany). Tris-Tween-NaCl (TTN) buffer (0.05M Tris, 0.3M NaCl, 1% Tween 20), carbonate buffer (15 mM Na2CO3, 35 mM NaHCO3, 0.001% phenol red, pH 9.6), AP substrate buffer (1M diethanolamine, 0.5 mM MgCl2, pH 9.8) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (10 mM Na2HPO4, 0.15M NaCl, pH 7.3) were from Statens Serum Institut (Hillerød, Denmark). Human IgG1 citrullinated fibrinogen mAb was from Modiquest (Nijmegen, The Netherlands, cat. no. MQR 2.101-100, clone 1F11). “Phycoerythrin”-conjugated anti-human IgG was from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Microspheres were from Luminex (Austin, TE). Peptides a–g (Table I), the remaining cyclic peptides [R2,H13]CCPb, [K2,K13]CCPb, [A2,A13]CCPb (Table I), resin-bound fibrinogen peptides and RA33 overlapping 20mer peptides (Uniprot KB ID: P22626) were from Schäfer-N (Lyngby, Denmark) (Supporting Information). Cyclization of peptides was conducted by air oxidation after peptide cleavage.

Peptide synthesis

Free peptides were synthesized in individual syringes using Fmoc-based SPPS on 2-chloro-trityl-resins as previously described.42 Briefly, Fmoc-protected amino acids were coupled in threefold excess to the peptide chain using DIC and HOAt. Fmoc deprotection was accomplished by treatment with 20% PIP in NMP for 10 min. The peptides were cleaved from the solid support along with the side chain-protecting groups using TFA:H2O:TIS:THIO (90:5:2.5:2.5) for 2 h at RT. The integrity of the synthetic peptides was examined by HPLC and mass spectrometry.

Using the sequence SHQEST-Cit-GRSRGRS as template, N- and C-terminally truncated resin-bound peptide series were synthesized essentially as previously described.34 The peptides were synthesized on Tentagel NH2 resin using a twofold excess of amino acids, DIC, and HOAt. After coupling of the underlined glycine residue, 20 mg resin was removed after each coupling cycle, generating 63 peptides in total. An exception was the first N-terminal truncated peptide series, which did not contain the underlined glycine residue, thus with citrulline being the first amino acid coupled to the resin. Side chain-protecting groups were removed as described previously.

High-performance liquid chromatography

Analytical HPLC was performed using a Waters C18-reversed-phase column (Symmetry_ C18 5 lM, 4.6 × 250 mm) (Waters, Milford, MA) on a Waters 600E system equipped with EMPOWER (Millenium, Waters, Milford, MA) software. Preparative HPLC was performed using a Vydac C18-reversed-phase column (10–15 lM, 25 × 250 mm) (VYDAC, Hesperia, CA).

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry was performed on a Bruker Flex (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany), using α-cyano-p-hydroxycinnamic acid as matrix and peptide standard calibration.

Peptide enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Peptides (10 μg/mL) were coated onto the surface of the wells of Maxisorp microtiter plates diluted in carbonate buffer for 2 h at RT. All incubations with antibodies diluted in TTN buffer (1 μg/mL) were carried out for 1 h at RT and followed by three washes in TTN buffer. Cit mAb and AP-conjugated anti-human IgG were used as primary and secondary antibodies, respectively. Finally, bound antibodies were quantified using pNPP (1 mg/mL) in AP substrate buffer. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm, with background subtraction at 650 nm, on a Thermomax microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, CA).

Luminex immunoassay

Briefly, 1.3 × 10−8 mol peptide was coupled to 6.25 × 105 preactivated carboxylated microspheres in 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid (50 mM, pH 5.0) by rotation for 2 h at RT. The beads were washed and stored in storage buffer (PBS, 0.1% BSA, 0.02% Tween-20, 0.05% NaN3, pH 7.4) at 4°C. Antigen–antibody interaction was measured by incubating ∼5000 beads with Cit mAb (1.0 μg/mL) for 1 h at RT. After washing with assay buffer (PBS, 1% BSA, pH 7.4), a phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-human IgG was added and incubated for 1 h at RT. Finally, ∼75 beads of each sample were acquired on a Bioplex reader (Biosource, Camarillo, CA), and antibody-antigen interaction was determined.

Screening of resin-bound peptides using modified enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Resin-bound peptides were added to a 96-well multiscreen filter plate (Millipore, Copenhagen, Denmark) and rinsed with TTN buffer. All incubations with antibodies (1 μg/mL) diluted in TTN were carried out for 1 h at RT followed by three washes in TTN buffer. The resin was washed with TTN buffer using a multiscreen vacuum manifold (Millipore, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Human Cit mAb and AP-conjugated anti-human IgG were used as primary and secondary antibodies, respectively. Bound antibodies were quantified using pNPP (1 mg/mL) diluted in AP substrate buffer. Finally, the buffer was transferred to a Maxisorp microtiter plate, and the absorbance was measured as described previously.

Statistical analysis

Statistical calculations were performed with repeated measurements (n = 2). The values obtained in this study were compared further by using the one-tailed Student's t-test for unpaired data, except from Figure 3, where some of the calculations were conducted using paired data.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Karen Duus for statistical assistance and Dorthe Tange Olsen and Bettina Eide Holm for technical assistance.

Supplementary material

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Sangha O. Epidemiology of rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology. 2000;2:3–12. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.suppl_2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedersen JK, Kjaer NK, Svendsen AJ, Horslev-Petersen K. Incidence of rheumatoid arthritis from 1995 to 2001: impact of ascertainment from multiple sources. Rheumatol Int. 2009;4:411–415. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0713-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridges SL. Update on autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2004;6:343–350. doi: 10.1007/s11926-004-0008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uysal H, Nandakumar KS, Kessel C, Haag S, Carlsen S, Burkhardt H, Holmdahl R. Antibodies to citrullinated proteins: molecular interactions and arthritogenicity. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:9–33. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhn KA, Kulik L, Tomooka B, Braschler KJ, Arend WP, Robinson WH, Holers VM. Antibodies against citrullinated proteins enhance tissue injury in experimental autoimmune arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:961–973. doi: 10.1172/JCI25422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trouw LA, Haisma EM, Levarht EW, van der Woude D, Ioan-Facsinay A, Daha MR, Huizinga TW, Toes RE. Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies from rheumatoid arthritis patients activate complement via both the classical and alternative pathways. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1923–1931. doi: 10.1002/art.24622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uysal H, Bockermann R, Nandakumar KS, Sehnert B, Bajtner E, Engstrom A, Serre G, Burkhardt H, Thunnissen MM, Holmdahl R. Structure and pathogenicity of antibodies specific for citrullinated collagen type II in experimental arthritis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:449–462. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Boekel MA, Vossenaar ER, van den Hoogen FH, van Venrooij WJ. Autoantibody systems in rheumatoid arthritis: specificity, sensitivity and diagnostic value. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:87–93. doi: 10.1186/ar395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schellekens GA, de Jong BA, van den Hoogen FH, van de Putte LB, van Venrooij WJ. Citrulline is an essential constituent of antigenic determinants recognized by rheumatoid arthritis-specific autoantibodies. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:273–281. doi: 10.1172/JCI1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Venrooij WJ, Pruijn GJ. Citrullination: a small change for a protein with great consequences for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2000;2:249–251. doi: 10.1186/ar95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burkhardt H, Sehnert B, Bockermann R, Engstrom A, Kalden JR, Holmdahl R. Humoral immune response to citrullinated collagen type II determinants in early rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1643–1652. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinloch A, Tatzer V, Wait R, Peston D, Lundberg K, Donatien P, Moyes D, Taylor PC, Venables PJ. Identification of citrullinated alpha-enolase as a candidate autoantigen in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R1421–R1429. doi: 10.1186/ar1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takizawa Y, Suzuki A, Sawada T, Ohsaka M, Inoue T, Yamada R, Yamamoto K. Citrullinated fibrinogen detected as a soluble citrullinated autoantigen in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fluids. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1013–1020. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.044743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vossenaar ER, Despres N, Lapointe E, van der Heijden A, Lora M, Senshu T, van Venrooij WJ, Menard HA. Rheumatoid arthritis specific anti-Sa antibodies target citrullinated vimentin. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:R142–R150. doi: 10.1186/ar1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Union A, Meheus L, Humbel RL, Conrad K, Steiner G, Moereels H, Pottel H, Serre G, De KF. Identification of citrullinated rheumatoid arthritis-specific epitopes in natural filaggrin relevant for antifilaggrin autoantibody detection by line immunoassay. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1185–1195. doi: 10.1002/art.10229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ioan-Facsinay A, Willemze A, Robinson DB, Peschken CA, Markland J, van der Woude D, Elias B, Menard HA, Newkirk M, Fritzler MJ, Toes RE, Huizinga TW, El-Gabalawy HS. Marked differences in fine specificity and isotype usage of the anti-citrullinated protein antibody in health and disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3000–3008. doi: 10.1002/art.23763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kokkonen H, Mullazehi M, Berglin E, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Ronnelid J, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S. Antibodies of IgG, IgA and IgM isotypes against cyclic citrullinated peptide precede the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R13. doi: 10.1186/ar3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li W, Wang M, Irigoyen P, Gregersen PK. Inferring causal relationships among intermediate phenotypes and biomarkers: a case study of rheumatoid arthritis. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1503–1507. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, de Jong BA, Berglin E, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Stenlund H, Sundin U, van Venrooij WJ. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2741–2749. doi: 10.1002/art.11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coenen D, Verschueren P, Westhovens R, Bossuyt X. Technical and diagnostic performance of 6 assays for the measurement of citrullinated protein/peptide antibodies in the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Chem. 2007;53:498–504. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.078063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schellekens GA, Visser H, de Jong BA, van den Hoogen FH, Hazes JM, Breedveld FC, van Venrooij WJ. The diagnostic properties of rheumatoid arthritis antibodies recognizing a cyclic citrullinated peptide. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:155–163. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<155::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiik AS, van Venrooij WJ, Pruijn GJ. All you wanted to know about anti-CCP but were afraid to ask. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10:90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, III, Birnbaum NS, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, Cohen MD, Combe B, Costenbader KH, Dougados M, Emery P, Ferraccioli G, Hazes JM, Hobbs K, Huizinga TW, Kavanaugh A, Kay J, Kvien TK, Laing T, Mease P, Menard HA, Moreland LW, Naden RL, Pincus T, Smolen JS, Stanislawska-Biernat E, Symmons D, Tak PP, Upchurch KS, Vencovsky J, Wolfe F, Hawker G. Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2569–2581. doi: 10.1002/art.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szodoray P, Szabo Z, Kapitany A, Gyetvai A, Lakos G, Szanto S, Szucs G, Szekanecz Z. Anti-citrullinated protein/peptide autoantibodies in association with genetic and environmental factors as indicators of disease outcome in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:140–143. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez ML, Gomara MJ, Ercilla G, Sanmarti R, Haro I. Antibodies to citrullinated human fibrinogen synthetic peptides in diagnosing rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3573–3584. doi: 10.1021/jm0701932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malakoutikhah M, Gomara MJ, Gomez-Puerta JA, Sanmarti R, Haro I. The use of chimeric vimentincitrullinated peptides for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Chem. 2011;54:7486–7492. doi: 10.1021/jm200563u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soos L, Szekanecz Z, Szabo Z, Fekete A, Zeher M, Horvath IF, Danko K, Kapitany A, Vegvari A, Sipka S, Szegedi G, Lakos G. Clinical evaluation of anti-mutated citrullinated vimentin by ELISA in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1658–1663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobylyansky AG, Nekrasov AN, Kozlova VI, Sandin MY, Alikhanov BA, Demkin VV. Detection of new epitopes of antibodies to filaggrin in filaggrin protein molecule. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2011;151:615–618. doi: 10.1007/s10517-011-1396-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundberg K, Kinloch A, Fisher BA, Wegner N, Wait R, Charles P, Mikuls TR, Venables PJ. Antibodies to citrullinated alpha-enolase peptide 1 are specific for rheumatoid arthritis and cross-react with bacterial enolase. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3009–3019. doi: 10.1002/art.23936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez ML, Gomara MJ, Ercilla G, Sanmarti R, Haro I. Antibodies to citrullinated human fibrinogen synthetic peptides in diagnosing rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3573–3584. doi: 10.1021/jm0701932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sebbag M, Moinard N, Auger I, Clavel C, Arnaud J, Nogueira L, Roudier J, Serre G. Epitopes of human fibrin recognized by the rheumatoid arthritis-specific autoantibodies to citrullinated proteins. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2250–2263. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willemze A, Bohringer S, Knevel R, Levarht EW, Stoeken-Rijsbergen G, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Van der Helm-van Mil AH, Huizinga TW, Toes RE, Trouw LA. The ACPA recognition profile and subgrouping of ACPA-positive RA patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:268–274. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ioan-Facsinay A, El-Bannoudi H, Scherer HU, van der Woude D, Menard HA, Lora M, Trouw LA, Huizinga TW, Toes RE. Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies are a collection of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies and contain overlapping and non-overlapping reactivities. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:188–193. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.131102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Woude D, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, Ioan-Facsinay A, Onnekink C, Schwarte CM, Verpoort KN, Drijfhout JW, Huizinga TW, Toes RE, Pruijn GJ. Epitope spreading of the anti-citrullinated protein antibody response occurs before disease onset and is associated with the disease course of early arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1554–1561. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.124537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williamson MP, Handa BK, Hall MJ. Secondary structure of a herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D antigenic domain. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1986;27:562–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Antigenic peptides. FASEB J. 1995;9:37–42. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.1.7821757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tarcsa E, Marekov LN, Mei G, Melino G, Lee SC, Steinert PM. Protein unfolding by peptidylarginine deiminase. Substrate specificity and structural relationships of the natural substrates trichohyalin and filaggrin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30709–30716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dorow DS, Shi PT, Carbone FR, Minasian E, Todd PE, Leach SJ. Two large immunogenic and antigenic myoglobin peptides and the effects of cyclisation. Mol Immunol. 1985;22:1255–1264. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(85)90044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mydel P, Wang Z, Brisslert M, Hellvard A, Dahlberg LE, Hazen SL, Bokarewa M. Carbamylation-dependent activation of T cells: a novel mechanism in the pathogenesis of autoimmune arthritis. J Immunol. 2010;184:6882–6890. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi J, Knevel R, Suwannalai P, van der Linden MP, Janssen GM, van Veelen PA, Levarht NE, van der Helm-van Mil AH, Cerami A, Huizinga TW, Toes RE, Trouw LA. Autoantibodies recognizing carbamylated proteins are present in sera of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and predict joint damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17372–17377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114465108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shoda H, Fujio K, Shibuya M, Okamura T, Sumitomo S, Okamoto A, Sawada T, Yamamoto K. Detection of autoantibodies to citrullinated BiP in rheumatoid arthritis patients and pro-inflammatory role of citrullinated BiP in collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R191. doi: 10.1186/ar3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trier NH, Hansen PR, Vedeler CA, Somnier FE, Houen G. Identification of continuous epitopes of HuD antibodies related to paraneoplastic diseases/small cell lung cancer. J Neuroimmunol. 2012;243:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.