Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study is to observe glycemic changes after emphasizing the importance of lifestyle modification in patients with mild or moderately uncontrolled type 2 diabetes.

Materials and Methods

We examined 51 type 2 diabetic patients with 7.0-9.0% hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) who preferred to change their lifestyle rather than followed the recommendation of medication change. At the enrollment, the study subjects completed questionnaires about diet and exercise. After 3 months, HbA1c levels were determined and questionnaires on the change of lifestyle were accomplished. We divided the study subjects into 3 groups: improved (more than 0.3% decrease of HbA1c), aggravated (more than 0.3% increase of HbA1c) and not changed (-0.3% <HbA1c change <0.3%).

Results

Among the total 51 subjects, 18 patients (35.3%) showed the decreased levels of HbA1c after 3 months with mean change of -0.74±0.27%, and HbA1c values of 11 patients (21.5%) were less than 7%. In addition, the HbA1c level was significantly reduced in patients who reportedly followed the lifestyle modification such as diet and exercise for 3 months, compared with the one obtained from patients who refused this lifestyle change (p=0.002).

Conclusion

In this study, 35.3% of the patients with mild or moderately uncontrolled type 2 diabetes showed the significant improvement of HbA1c levels after 3 months by simply regulating their daily diet and exercise without change of medication. This suggests that the lifestyle modification is significantly associated with the improvement of glucose control.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, glycemic control, lifestyle, modification

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a major chronic disease, and its prevalence rate is continuously increasing worldwide. It also causes a variety of microvascular complications and acts as a major risk factor in cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, control of those chronic complications is a critical step in diabetic patients, and it can be achieved by strictly managing the level of blood glucose.1-5 American Diabetes Association (ADA) and European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) defined the diabetes and suggested the standards of medical care in diabetes including pharmacologic treatment, medical nutrition therapy (MNT) and physical activity. For instance, if the level of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) does not reach 7% for a certain period after treatment of metformin in combination with lifestyle change (MNT and exercise), they recommend additional medication such as sulfonylurea, insulin, or pioglitazones. Nevertheless, if HbA1c targets are not achieved, treatment intensification is based on the addition of another agent from a different class and maintenance of lifestyle modification.6 However, most individuals have hard time to continuously carry on restriction of food intake and regular exercise activity even if they are clinically diagnosed as diabetes. Furthermore, physicians in busy outpatient clinics cannot coerce patients to keep the lifestyle modification, and also cannot evaluate and control them from many coexisting comorbidities, which generally lead to high glucose level.

Because of these above-mentioned reasons, physicians openly recommend patients to take high dose of oral hypoglycemic agents (OHA) and additional insulin therapy rather than reversible approach such as lifestyle modification to effectively control glucose level. However, patients sometimes refuse to accept this medication change or insulin treatment. There is no report on a significant change of blood glucose after reemphasis on the importance of lifestyle change in diabetic patients whose HbA1c levels were not properly controlled and who refused additional medication.

In this study, we examined how reemphasis on the importance of lifestyle modification influences glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients who were reluctant to undergo additional medication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The study involved patients with type 2 diabetes (n=75) who visited the outpatient department of endocrinology and metabolism in our hospital (Gyeongsang National University Hospital) from Oct. 2010 to Jan. 2011 and refused additional medicines and kept HbA1c levels of 7.0-9.0% although they were treated with OHAs for over 3 months. However, this research was carried out with only 51 patients who did not follow diet control or regular exercise at the beginning of the study. We excluded 24 patients who carried out both diet and exercise, who were under 95% in the drug compliance, who were undergoing treatment for hyperthyroidism or a malignant neoplasm, who were taking steroids, who needed operation and hospitalization due to infectious diseases or myocardial infarction 6 months prior to the start of this study, and who did not agree with this study or did not revisit the hospital 3 months later, although they signed for this study.

Methods

For the patients who agreed with this study, we verified and examined age, gender, duration of diabetes, drinking, smoking, education, occupation, family history of diabetes, level of HbA1c 3 months ago, height, and weight through interview or medical records. We surveyed daily diet and exercise of the patients and asked "you have to control your diet" or "you have to do more exercise" based on survey data when the patients who had hard time to keep diet and exercise under control.

In the survey for diet, we asked the patients to select the following 4 answers to the question "Did you keep your daily adequate calories in diet?", 1) I did not try to control the diet and had unlimited extra meal, 2) I had several extra meals and ignored daily adequate calories, 3) I tried to keep daily adequate calories as possible as I can, and 4) I followed exact daily adequate calories as prescribed. In the survey for exercise, we asked the patients to select the following 4 answers to the question "how long did you exercise so as to bedrenched in sweat on your back per week?", 1) none, 2) less 60 min a week, 3) 60-150 min a week, and 4) more than 150 min a week. We considered the patients who chose answer #1, or #2 from the both above questionnaires as a candidate for this study, because they did not properly carry out diet or exercise control. We examined HbA1c levels three months later and asked them to answer to questionnaires again to confirm how they carried out the diet and exercise control. We considered it "improved" if HbA1c levels were decreased more than 0.3% compared with the values at the beginning of study, "aggravated" if they were increased more than 0.3%, and "not changed" if they were at the range of -0.3%<ΔHbA1c<0.3%. We re-categorized the patients according to the lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) when their answers were either #3 or #4 after three months.

We examined fasting plasma glucose level, fasting insulin, C-peptide, total cholesterol level, high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides, serum creatinine, and albumin-to creatinine ratio in a spot urine. We also calculated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) using Cockcroft-Gault equation. Insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) values were determined from the equation [fasting insulin (µU/mL)×fasting glucose (mmol/L)]/22.5, and it was considered to be insulin resistance if the values were higher than 1.75.

This study was performed with the approval of the ethical committees at Gyeongsang National University Hospital. All patients agreed with this study after understanding the details of research methods and aims.

Statistics

All data were statistically analyzed by PASW 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data in figures represent mean (±standard deviation) values. Difference between two groups was evaluated by non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test, and difference between discrete variables was verified by Pearson chi-square test. Correlation between two groups was determined by Pearson's correlation coefficient. p<0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of patients at the beginning of the study

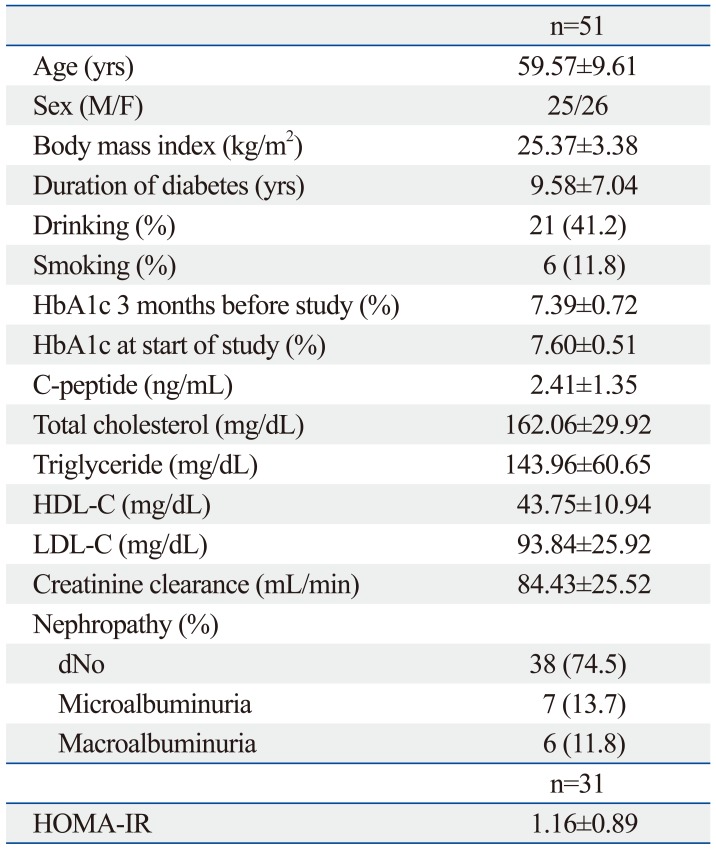

The gender ratio of the patients involved in this study was 25 : 26 (male : female), and their average age was 59.57±9.61 years. The average diabetic duration of patients was 9.58±7.04 years, and their body mass index (BMI) was 25.37±3.38 kg/m2. Among 51 patients, 16 patients carried out the regular exercise but not the diet control, 4 patients followed the diet control only, and 30 patients did not change both diet and exercise during the research period of three months (Table 1). The average level of HbA1c of all patients at three month before the beginning of this study and during the study was 7.39±0.72%, and 7.60±0.51%, respectively, while 64.7% patients (33/51 total) showed HbA1c higher than 7.0% (Table 1). The C-peptide concentration was 2.41±1.36 ng/mL, total cholesterol was 162.06±29.92 mg/dL, triglycerides were 143.96±60.65 mg/dL, HDL was 43.75±10.94 mg/dL, and LDL was 93.84±25.92 mg/dL. The average GFR of patients was 93.84±25.92 mg/dL, and 13 patients (25.5%) were associated with diabetic nephropathy. We examined HOMA-IR in only 31 patients, and found the value of 1.16±0.89 (Table 1). Even though we did not measure the weight of all patients after three months, we observed no significant change of weight among 32 patients who had been weighed at every visit during three months.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics of the Study Subjects

Data are shown as n (%) or means±SD. HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment-insulin resistance.

Analyses of blood glucoses and other factors after three months of study

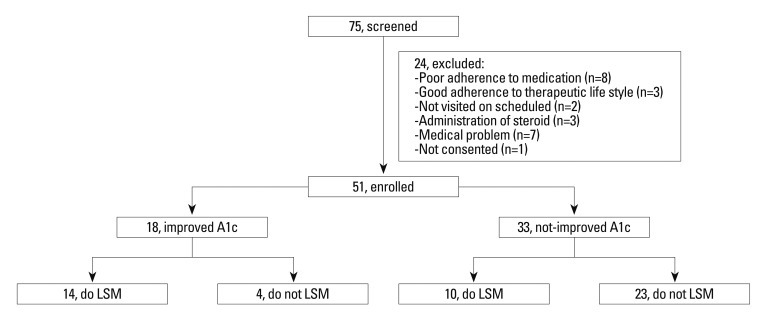

Three months after the study, 18 patients (35.3%) showed a decrease of HbA1c level, and their average HbA1c level was 6.97±0.47%, indicating a decrease of 0.74±0.27% (Fig. 1). On the other hand, 33 patients (64.7%) revealed no change or rather a slight increase of HbA1c (average of this group, 7.92±0.76%) compared with the beginning value (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study. LSM, lifestyle modification.

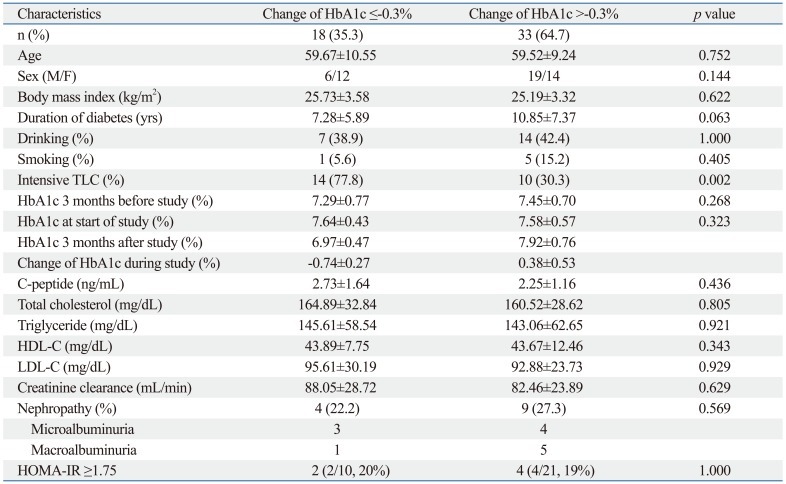

Table 2.

Comparisons of Clinical Factors between Patients with Decreased HbA1c Levels and Patient with Unchanged or Increased HbA1c Levels at the 3-Month Follow-Up Examination

HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment-insulin resistance; TLC, therapeutic lifestyle modification.

Total 24 patients actually changed their diet and exercise lifestyle because of clinician's recommendation, and 14 of them showed a significant improvement of the HbA1c level. Only lifestyle modification was statistically correlated to the decrease of HbA1c (p=0.002). When HbA1c levels at the beginning were divided into four different ranges (7.0-7.5%, 7.6-8.0%, 8.1-8.5%, 8.6-9.0%), HbA1c change was not significant compared with the values three months later. Furthermore, there is no significant change in plasma glucose (data not shown). However, any other factors, such as C-peptide, insulin resistance, age, gender, duration of diabetes, BMI, smoking, drinking, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, GFR, or diabetic nephropathy, did not significantly affect the change of HbA1c level after three months (Table 2).

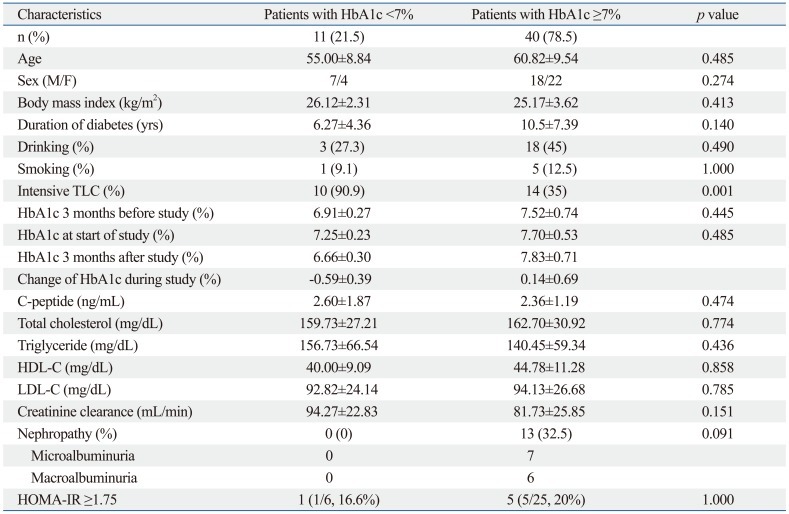

Effect of other factors to reach target level of blood glucose

After three months, 11 patients (21.5%) showed a target range of HbA1c level (below 7%). Their average HbA1c was 6.66±0.30%, decreased by 0.59±0.39% from the value at the beginning of the study. In contrast, however, 40 patients (78.5%) had a HbA1c of over 7%. The average HbA1c of these patients was 7.83±0.71%, which was increased by 0.14±0.69% compared with the one three months ago (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparisons of Clinical Factors between Patients with HbA1c <7% and Patients with HbA1c ≥7% at the 3-Month Follow-Up Examination

HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment-insulin resistance; TLC, therapeutic lifestyle modification.

Among these 11 patients who reached the target HbA1c level (below 7.0%), 10 patients answered "Yes" to the question of "did you exactly follow the lifestyle modification". Also, 14 out of 40 patients who failed to reach the target HbA1c level answered "Yes" to this question. Statistical analyses of these data indicated that the lifestyle modification was strongly associated with the decrease of HbA1c to below 7% (p=0.001), but not other factors including age, gender, duration of diabetes, HbA1c level three months prior to or when this study began, C-peptide, insulin resistance, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, GFR, or diabetic nephropathies (Table 3).

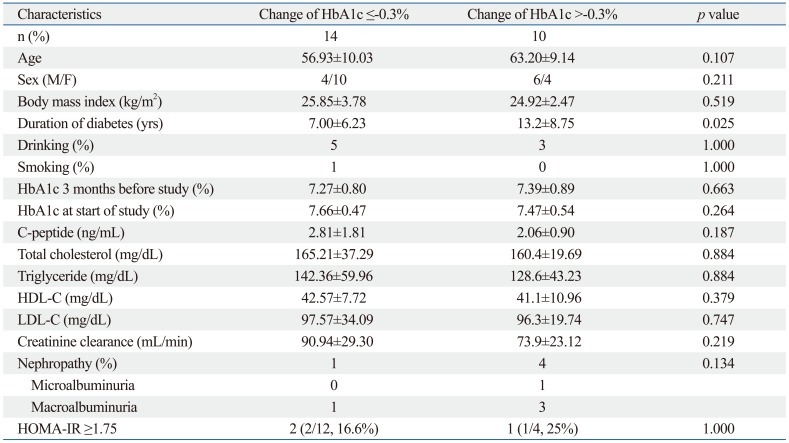

Finally, we compared overall relationship between lifestyle modification and HbA1c level. Among the 24 patients who carried out the lifestyle modification well, a decrease of HbA1c levels after three months was observed in only 14 patients, whereas 10 patients showed no change or slight increase in HbA1c level. These 10 patients were found to have significantly longer duration of diabetes compared to the other 14 patients whose HbA1c levels were decreased (p=0.025) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparisons of Clinical Factors between Patients with HbA1c <7% and Patients with HbA1c ≥7% Who Intensified Therapeutic Lifestyle Change for 3 Months

HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol.

DISCUSSION

The type 2 diabetic patients generally take more than two medicines for lowering blood glucose, but they encounter unsuccessful glycemia in many cases. In this study we analyzed the relationship between the pattern of lifestyle and glycemic control with 75 patients who refused additional medication, and instead, intended to change the lifestyle. However, 51 patients did not follow the diet and exercise control which we recommended. We re-emphasized this lifestyle modification to these patients and examined HbA1c levels after three months. Eighteen patients (35.5%) showed a decrease of HbA1c. In particular, the HbA1c level of 11 patients (21.5%) was below 7.0% after three months.

These results strongly indicate that the glucose level of about 20% patients who had no intention to control diet or regular exercise improved to normal range through one-time education about lifestyle modification only in the outpatient clinics. In this study, 77.8% of patients who showed decreased HbA1c level indicated that they actually carried out the lifestyle modification. In particular, the diet and exercise control was carried out by over 90% patients who had a decrease of HbA1c to less 7%, suggesting again that counseling and education about lifestyle modification are very important in type 2 diabetic patients who are taking medicines, and this can improve the glucose level of patients without additional medication.

Lifestyle modification including a regular exercise and diet control is absolutely necessary for not only glucose control in type 2 diabetic patients but also prevention of diabetic complications.7-9 It also influences glucose level and other risk factors for diabetes. For examples, Japan Diabetes Complication Study reported that glucose levels in 2205 type 2 diabetic patients were significantly improved by lifestyle modification.10 According to the study performed in Costa Rica, the weight, glucose level, and HbA1c of diabetic patients were significantly decreased after public health intervention addressing nutrition and exercise.11 Furthermore, this lifestyle modification reduced diabetes-related risk factors such as glucose level, hypertension, or cholesterol and diabetic complications in Swedish diabetic patients.12

Surprisingly, we showed here in a large-scale study that a simple education and mention for diet and exercise resulted in improvement of glucose level without systematic education and intervention of this lifestyle modification. Based on the present result, we recommend that counseling for a regular exercise and diet control as well as taking medicines is required for all diabetic patients in the clinic, and further suggest to hold the treatment of additional medications, such as insulin, for at least 3 months if the patients who failed to reach a target range of glucose are willing to strictly modify their lifestyle. Furthermore, we expect that the systematic approach for change of lifestyle might help gradually decrease glucose level in type 2 diabetic patients.

Progression of type 2 diabetes is typically accompanied with a gradual decrease of insulin secretion due to the loss of β-cells mass and decline of their function. Based on United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, type 2 diabetic patients have general defect on insulin secretion. Its capacity in diabetic patients is decreased to 50% compared with normal persons and to 25% at 6 years after being diagnosed.1 Therefore, earlier insulin treatment is recommended because of decrease of insulin secretion. Indeed, according to ADA/EASD guidelines published in 2009, an early insulin treatment is recommended in diabetic patients if their HbA1c levels are over 7%.6

Our result is not against an early insulin treatment, but we rather suggest that there are some possible ways to improve the glucose levels by re-emphasizing the lifestyle modification in patients who are reluctant to the treatment of additional medicines. Aas, et al.13 also reported that lifestyle intervention based on exercise and diet counseling was as effective as insulin treatment. This result was further supported by a study which showed the betterment of glucoses via change of lifestyle in the type 2 diabetic patients who reveal psychological resistance to additional insulin therapy.14

As shown in the present results, the patients (n=10) with no change or increase in HbA1c levels after three months had a relative long duration period of diabetes, although they answered "Yes" to the question of "did you exactly follow the lifestyle modification". Therefore, it is suggested that more systematic and close approach would be necessary for the patients who have relatively long duration of diabetes and poor adherence to the therapeutic life style change.

In this study we did not examine the frequency of hypoglycemia before and after the study, and also excluded the patients who had reversible factors causing a temporal increase of glucose level or poor compliance by taking medicines. Furthermore, this study has several limitations. First, we measured only HbA1c levels at a certain period after re-emphasis of lifestyle modification without SMBG. Second, we observed relatively short period (three months) and small numbers of patients for this study. Finally, drug compliance was totally dependent on patient' comment without systematic and logical survey.

In conclusion, we showed herein that a significant improvement of glycemic control was achieved by a simple educational emphasis of "you have to do more exercise and control your daily diet" in a number of type 2 diabetic patients who wanted to keep the current treatment of medicines although their glycemic control was mild or moderately uncontrolled. This result suggested that we can motivate patients to be more concerned and carry out lifestyle modification via counseling in out-patient clinics. However, we need further systematic and long-term follow up studies to confirm the solid relation between the lifestyle modification and blood glucose control in a large group of patients who fail to reach the target level of blood glucose by treatment of OHAs alone.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Gyeongsang National University Hospital Research Fund (2011), and Basic Science Research program through the national research foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012-0000305, and 2012R1A1A4A01015109).

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basevi V, Di Mario S, Morciano C, Nonino F, Magrini N. Comment on: American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2011. Diabetes Care 2011;34(Suppl. 1):S11-S61. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:e53. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adler AI, Stratton IM, Neil HA, Yudkin JS, Matthews DR, Cull CA, et al. Association of systolic blood pressure with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 36): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:412–419. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodbard HW, Jellinger PS, Davidson JA, Einhorn D, Garber AJ, Grunberger G, et al. Statement by an American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology consensus panel on type 2 diabetes mellitus: an algorithm for glycemic control. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:540–559. doi: 10.4158/EP.15.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, Wang JX, Yang WY, An ZX, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:537–544. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hämäläinen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sone H, Katagiri A, Ishibashi S, Abe R, Saito Y, Murase T, et al. Effects of lifestyle modifications on patients with type 2 diabetes: the Japan Diabetes Complications Study (JDCS) study design, baseline analysis and three year-interim report. Horm Metab Res. 2002;34:509–515. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Goldhaber-Fiebert SN, Tristán ML, Nathan DM. Randomized controlled community-based nutrition and exercise intervention improves glycemia and cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetic patients in rural Costa Rica. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:24–29. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krook A, Holm I, Pettersson S, Wallberg-Henriksson H. Reduction of risk factors following lifestyle modification programme in subjects with type 2 (non-insulin dependent) diabetes mellitus. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2003;23:21–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-097x.2003.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aas AM, Bergstad I, Thorsby PM, Johannesen O, Solberg M, Birkeland KI. An intensified lifestyle intervention programme may be superior to insulin treatment in poorly controlled Type 2 diabetic patients on oral hypoglycaemic agents: results of a feasibility study. Diabet Med. 2005;22:316–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Guzman S, Villa-Caballero L, Edelman SV. Psychological insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes: the scope of the problem. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2543–2545. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]